Abstract

How specific features in the environment are represented within the brain is an important unanswered question in neuroscience. A subset of retinal neurons, called direction selective ganglion cells (DSGCs) are specialized for detecting motion along specific axes of the visual field1. Despite extensive study of the retinal circuitry that endows DSGCs with their unique tuning properties2,3, their downstream circuitry in the brain and thus their contribution to visual processing has remained unclear. In mice, several different types of DSGCs connect to the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN),4,5,6 the visual thalamic structure that harbors cortical relay neurons. Whether direction selective information computed at the level of the retina is routed to cortical circuits and integrated with other visual channels, however, is unknown. Here we show using viral trans-synaptic circuit mapping7,8 and functional imaging of visually-driven calcium signals in thalamocortical axons, that there is a di-synaptic circuit linking DSGCs with the superficial layers of primary visual cortex (V1). This circuit pools information from multiple types of DSGCs, converges in a specialized subdivision of the dLGN, and delivers direction-tuned and orientation-tuned signals to superficial V1. Notably, this circuit is anatomically segregated from the retino-geniculo-cortical pathway carrying non-direction-tuned visual information to deeper layers of V1, such as layer 4. Thus, the mouse harbors several functionally specialized, parallel retino-geniculo-cortical pathways, one of which originates with retinal DSGCs and delivers direction- and orientation-tuned information specifically to the superficial layers of primary visual cortex. These data provide evidence that direction and orientation selectivity of some V1 neurons may be influenced by the activation of DSGCs.

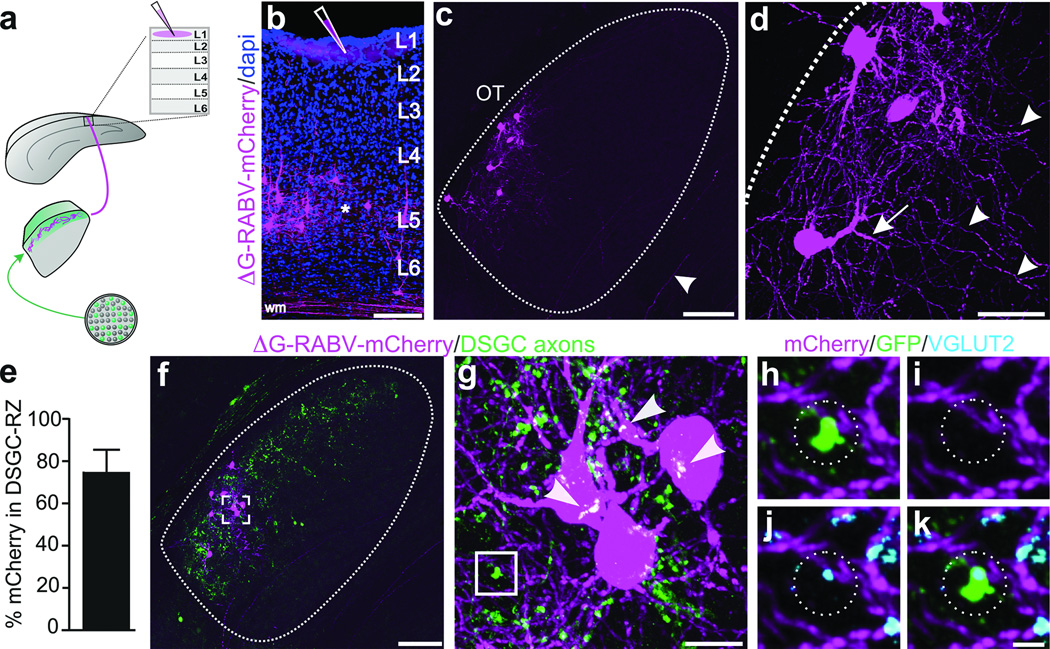

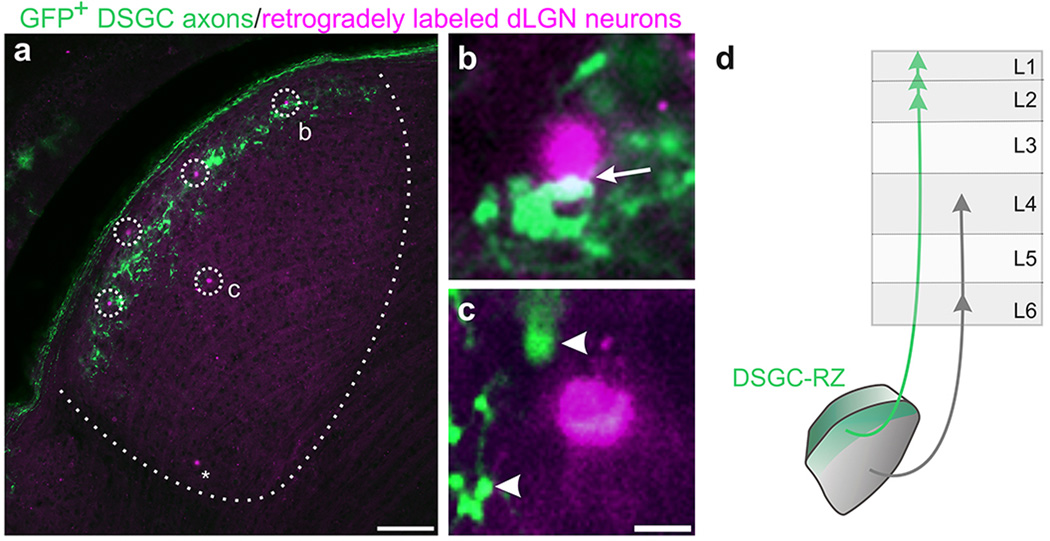

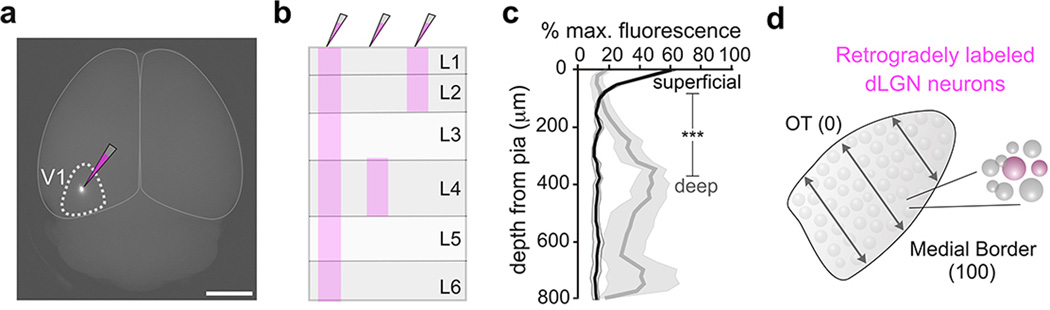

Visual perception involves the activity of neurons in the cerebral cortex. The most direct route for visual information to reach the cortex is via the ‘retino-geniculo-cortical pathway’ consisting of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), relay cells in the dLGN and neurons in primary visual cortex (V1) (Extended Data Figure 1a–c)9. Recently, we and others discovered that direction selective retinal ganglion cells (DSGCs) project to the dLGN and therein target a specific layer in the lateral ‘shell’ 4,5,6,10 (Fig. 1a–c). Hereafter we also refer to this layer as the DSGC-recipient zone or ‘DSGC-RZ’ (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. The layer of the dLGN that receives input from DSGCs projects to V1.

a, GFP+ DSGC axons in dLGN. OT: Optic tract. Inset: GFP+ boutons. d: dorsal, m: medial. b, merged GFP/CTβ−594 (all RGC axons) and c, with dapi (cell nuclei). a–c, Scale, 125 µm. d, Summary. e, AAV2-tdTomato injection to dLGN. Asterisk: tdTomato+ neurons in core. Scale, 100 µm. f, tdTomato+ thalamocortical axons in V1. (L1-6, layers 1–6; wm: white matter). Scale, 150 µm. Higher magnification of (g) L4, (h) L5 and L6 and (i) L1 and L2. Arrows: axons in L1. Scale, g, h, 50 µm. Scale, i, 100 µm. 16 mice.

Previous work showed that the dLGN shell receives input from the superior colliculus11 and thus, like other thalamic compartments12, neurons in the shell/DSGC-RZ may restrict their connections to subcortical networks, rather than participating in the retino-geniculo-cortical pathway. We infected neurons in the dLGN shell and a small portion of the dLGN core by injections of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-tdTomato (Fig. 1e). Within V1, tdTomato+ axons were observed in deeper layers 4 and 6 and superficial layers 1 and 2 (Fig. 1f–i). Thus, neurons in the shell/DSGC-RZ likely include thalamocortical relay neurons, but it was unclear whether they target specific V1 layers.

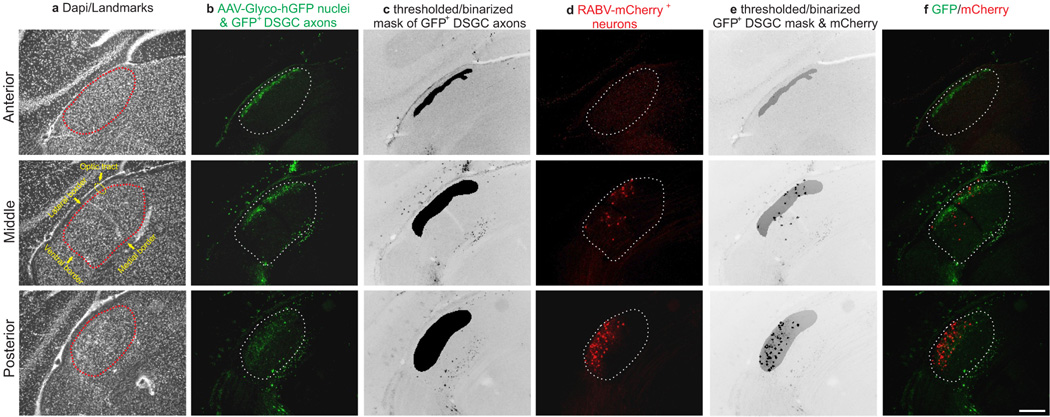

To determine whether there is laminar specificity of mouse geniculo-cortical connections we injected retrograde tracers into different V1 layers (Fig. 2a–c) and analyzed the position of the retrogradely labeled neurons in the dLGN (Fig. 2d–i) (Extended Data Figure 2a–c). Injections of all V1 layers retrogradely labeled cells across the full width of the dLGN (Fig. 2a,d,g). By contrast, injections directed to V1 layer 4 preferentially labeled neurons in the dLGN core (Fig. 2b,e,h) and injections into superficial V1 layers 1 and 2 preferentially labeled neurons in the dLGN shell/DSGC-RZ (Fig. 2c,f,i) (Extended Data Figure 3a–c). These laminar-specific patterns of retrograde labeling were independent of retinotopy or eye-specific connectivity (Extended Data Figure 4) and together they indicate that cells in the dLGN core project to deeper V1, whereas cells in the dLGN shell/DSGC-RZ preferentially target superficial V1 (Extended Data Figure 3d).

Figure 2. Parallel, layer-specific thalamocortical circuits in the mouse.

Tracer injections to a, all V1 layers b, layer 4 and c, superficial V1. d–f, dLGN neurons labeled after (d) full depth injection (asterisk: axons of L6 neurons; yellow box, neurons in shell; green box, middle; blue box, core) e, deep V1 injection and f, superficial V1 injection (arrows: labeled cells; arrowhead: labeled cell outside shell.) g–i, Position of retrogradely labeled cells along dLGN width: g, Full depth: 35.54 ± 1.62% (4 mice; n= 232 cells); h, deep : 68.53 ± 1.22 % (4 mice; n= 69 cells); i, superficial: 14.68 ± 1.57 % (4 mice; n= 78 cells). Superficial vs. deep= ***P<0.0001; Tukey’s multiple comparisons. c, Scale, 200 µm. f, Scale, 100 µm.

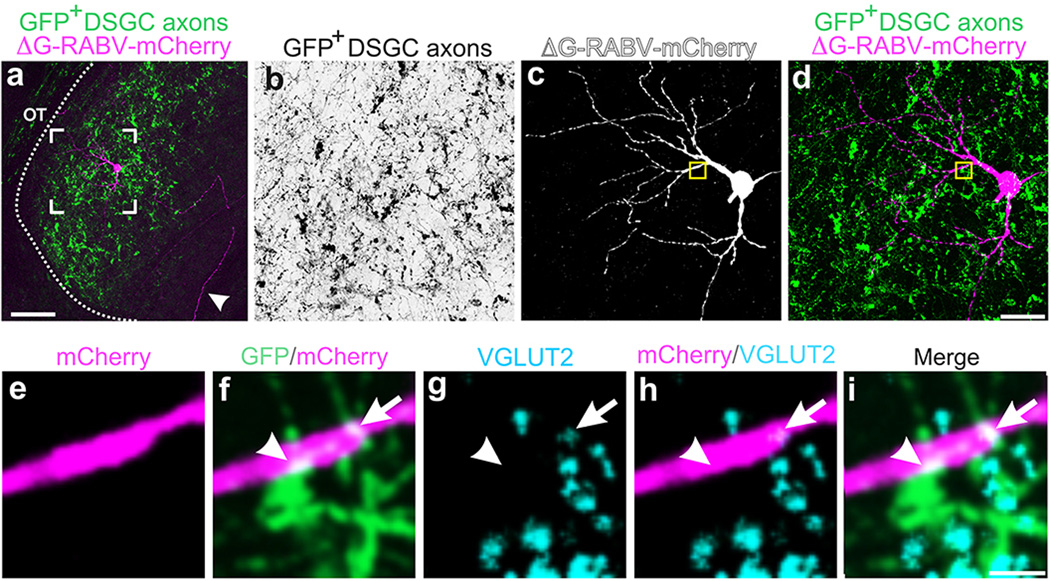

RGC axons synapse onto the somas and dendrites of dLGN neurons13, the latter of which are not entirely labeled using traditional retrograde tracing methods. Thus, we extended our exploration of the connections between DSGCs and thalamocortical relay neurons using a glycoprotein-deleted rabies virus expressing mCherry (ΔG-RABV-mCherry) that infects neurons at the level of their axon terminals, leading to golgi-like expression of mCherry throughout the infected cell. We note, however, that by itself, ΔG-RABV-mCherry but does not pass trans-synaptically7,8. Following injections of ΔG-RABV-mCherry into superficial V1 (Fig. 3a,b) we observed relay neurons in the dLGN shell expressing mCherry throughout their somas and dendritic arbors (Fig. 3c,d). By performing these experiments in mice with genetically tagged DSGCs, we determined that the majority of the mCherry+ cells resided in the DSGC-RZ (Fig. 3e,f) (Extended Data Figure 4) (Methods). We observed putative sites of contact between the axon terminals of DSGCs and the dendrites of mCherry+ dLGN neurons (Fig. 3g), some of which contained VGLUT2 (Fig. 3h–k) (Extended Data Figure 5), a presynaptic glutamate transporter that in the dLGN, arises solely from RGC axon terminals14. Together, these experiments indicate that the neurons in the dLGN shell/DSGC-RZ that project to superficial V1 are contacted by, and likely receive synaptic input from, On-Off DSGCs.

Figure 3. DSGC axons contact thalamic relay neurons projecting to superficial V1.

a, ΔG-RABV-mCherry injection to superficial V1, to infect axons of DSGC-RZ neurons. b, V1 injection. Asterisk: infected L5/6 neurons. Scale, 200 µm. c,d, mCherry+ dLGN neurons. Arrowhead, axon. Scale, 75 µm. d, Arrows: proximal and arrowheads: distal, dendrites. Scale, 25 µm. e, % mCherry somas within GFP+ DSGC-RZ (74.77 ± 0.12%; 8 mice, n= 83 cells) (Extended Data Figure 4). f–h, DSGC axons and dLGN somas and dendrites. g, magnified view of frame in f. Arrowheads, putative contact sites13f, Scale, 125 µm. g, 20 µm. h–k. GFP, mCherry, VGLUT2 (% mCherry signal contacted by GFP+/VGLUT2+ profiles= 5.23 ± 1.39; 4 mice; n= 4 cells). k, Scale, 2 µm.

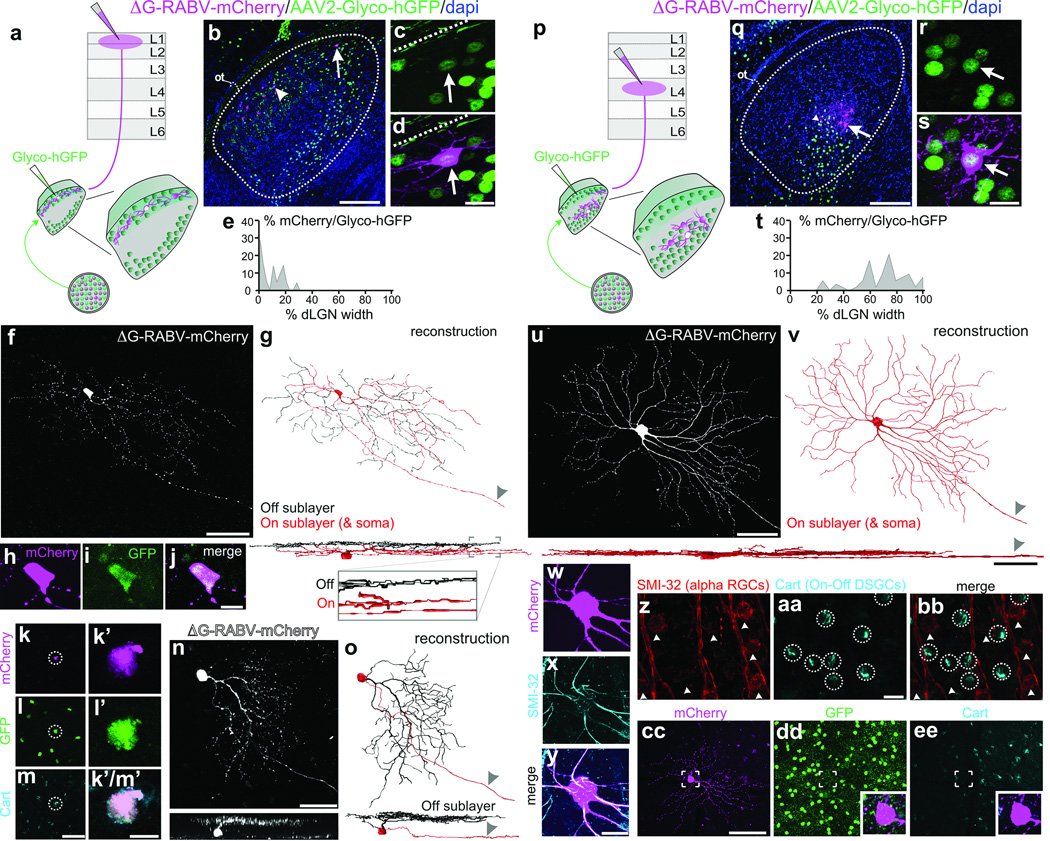

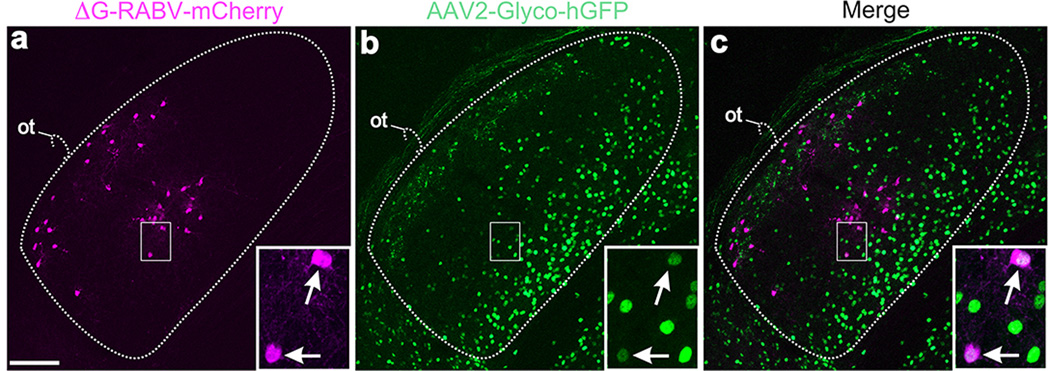

To determine whether there is a bona fide di-synaptic circuit linking DSGCs to superficial V1, we used rabies-virus trans-synaptic network tracing7,8. We injected ΔG-RABV-mCherry into superficial V1 to infect neurons in the dLGN shell/DSGC-RZ via their presynaptic terminals and in the same mice, we infected dLGN neurons with an AAV expressing rabies glycoprotein/histone-tagged GFP (AAV2-Glyco-hGFP) (Fig. 4a). In this experimental configuration, the double-infected RABV-mCherry+/Glyco-GFP+ dLGN relay neurons produce infectious ΔG-RABV-mCherry that propagates trans-synaptically to infect and label the RGCs that synapse onto them (Fig. 4a) (Methods). A small number of double-infected cells were present in the dLGN and these were always located in the shell/DSGC-RZ (Fig. 4b–e) (8 mice, n= 21 cells). Moreover, we performed these experiments in mice where GFP is selectively expressed by posterior-tuned On-Off DSGCs5,6 (Extended Data Figure 6) and we used immunohistochemical markers that recognize multiple On-Off DSGC types15,16 to determine i) whether DSGCs provide di-synaptic input to V1, and ii) if so, whether multiple DSGC types feed this pathway.

Figure 4. Synaptic circuit linking DSGCs to superficial V1, and non-DSGCs to L4.

a, Trans-synaptic tracing. b, Infected dLGN neurons. Arrow, arrowhead: double-infected cells. Scale, 100 µm. c,d, Cell from b. Scale, 15 µm. Dashed line: lateral border. e, Distribution of double-infected dLGN cells = 9.29 ± 1.82% (8 mice, n= 21 cells). f, On-Off DSGC trans-synaptically labeled from superficial V1. g, On (red) and Off (black) dendrites. Arrowhead: axon. Scale, 50 µm. h–j, Cell (f) is GFP+ On-Off DSGC6. Scale, 10 µm. k–m’, Trans-synaptically labeled GFP+ and Cart+ DSGC5m, Scale, 75 µm. m’, 10 µm. n, Trans-synaptically labeled J-RGC4o, Off dendrites (black). Scale, 50 µm. p, Same as a, but layer 4 injection. q–s, Infected neurons in core; q, arrow, arrowhead: double-infected cells. Scale, 100 µm. r,s, Cell from q (arrow). s, Scale, 15 µm. t, Distribution of double-infected dLGN cells= 70 ± 2.65% (7 mice, n= 53 cells) (P< 0.0001 versus e; two-tailed t-test). u,v, Alpha RGC labeled from V1 layer 4. u, Scale, 100 µm; sideview, 50 µm. w–y, cell (u,v), SMI-32+. Scale, 20 µm. z–bb, SMI-32 and Cart. Scale, 25 µm. cc–ee, ΔG-RABV-mCherry+ alpha RGC; lacks GFP6 and Cart. Scale, 150 µm.

In mice with 1–3 double-infected dLGN neurons we observed 1–3 mCherry+ RGCs, which is consistent with the convergence of mouse retinogeniculate connections17. An example is shown in Fig. 4f,g. The cell has thin dendrites and looping arborizations and is bistratified in the On and Off sublayers of the inner plexiform layer (IPL) (Fig. 4g, and inset), features characteristic of On-Off DSGCs2,3,5,6. Also, the RGC is GFP+ in a transgenic mouse where GFP is selectively expressed in posterior-tuned On-Off DSGCs5 (Fig. 4h–j) (Extended Data Figure 7). Another mCherry+ DSGC trans-synaptically labeled from superficial V1 is displayed in Fig. 4k–m’. The cell expresses cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (Cart), a marker of On-Off DSGCs15,16. Interestingly, trans-synaptic tracing from superficial V1 also labeled J-RGCs, which are asymmetric Off-type DSGCs tuned for upward motion4 (Fig. 4n–o).

Of all the RGCs trans-synaptically labeled from superficial V1 we verified that the vast majority were DSGCs (n= 27/28 cells; 8 mice). 17/28 were genetically identified as posterior-tuned On-Off DSGCs5,6 and 9/28 were Cart+ but not GFP+ and thus are On-Off DSGCs which likely are tuned to other cardinal axes of motion15,16. 1/28 was an upward tuned J-RGC4, and one could not be classified. Thus, while we cannot conclude that only DSGCs contribute to this pathway, we find that several types of On-Off DSGCs as well as Off-type DSGCs provide di-synaptic input to superficial V1.

Do DSGCs also feed the classic retino-geniculo-cortical pathway into layer 4? We addressed this by injecting mice with ΔG-RABV-mCherry into V1 layer 4 and AAV2-Glyco-hGFP into the dLGN, then examining the RGC types trans-synaptically labeled with mCherry (Figure 4p). In this regime, the mCherry+/ Glyco-hGFP+ double-infected neurons resided in the dLGN core (Fig. 4q–t) (Extended Data Fig. 8) (7 mice, n= 53 cells) (Fig. 4t versus Fig. 4e; ***P<0.0001; two-tailed t-test). All the RGCs trans-synaptically infected from layer 4 had large somas and broad, smooth monostratified dendrites, features characteristic of mouse alpha RGCs18,19 (Fig. 4u–v) and/or they expressed SMI-32, a marker of alpha RGCs18 (Fig. 4w–y) (7 mice, n= 38 RGCs) that is not expressed by On-Off DSGCs (Fig. z-bb). Moreover, none of the RGCs trans-synaptically infected from layer 4 exhibited DSGC morphologies, stratification patterns, or molecular/genetic markers4,5,6,15,16 (Figure 4cc–ee) (0/38 RGCs examined; 7 mice). Combined with the results in Figs. 2, 3, 4a–o, these data indicate that alpha, non-direction-tuned RGCs are poised to influence layer 4 of V1 via neurons in the dLGN core, whereas DSGCs are poised to influence superficial V1 via neurons in the dLGN shell.

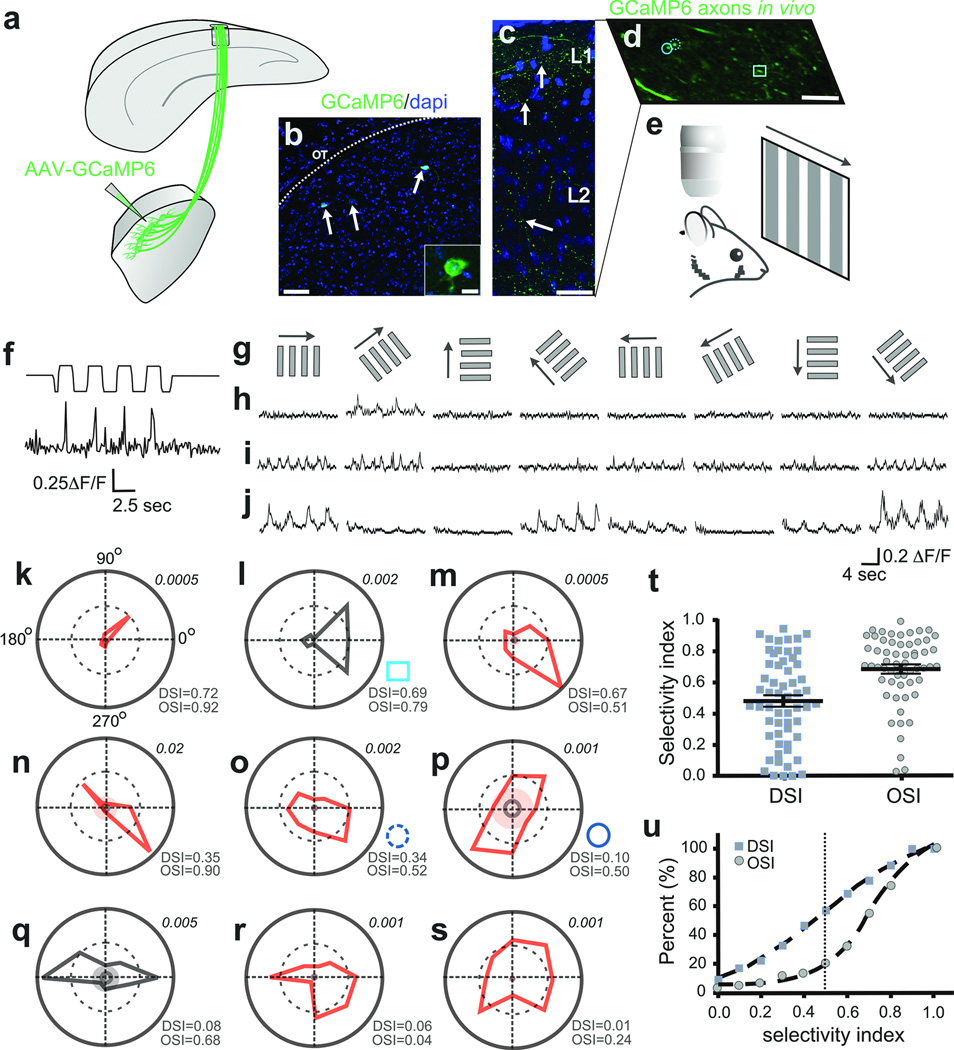

Next we asked what qualities of visual information are delivered by the dLGN to superficial V1. We forced a subset of dLGN neurons to express the calcium indicator GCaMP6[ref 20] by injections of AAV2-Syn-GCaMP6 into the shell/DSGC-RZ (Fig. 5a–c) (5 mice). We then imaged the visually-evoked calcium dynamics (ΔF/F) in thalamocortical axons that target superficial layers of V1 (Fig. 5d) using in vivo time-lapse two-photon microscopy20 (Fig. 5e), while presenting the mice with drifting gratings of different orientations and directions (Fig. 5e–g) (Methods).

Figure 5. In vivo imaging of visually-evoked Ca++ signals in thalamocortical axons.

a, AAV2-GCaMP6 injection to dLGN shell b, GCaMP6+ neurons (arrows). Scale, 50 µm; inset, 10 µm. c, GCaMP6+ dLGN axons, superficial V1. Arrows: varicosities. Scale, 50 µm. d, GCaMP6+ axons, superficial V1. Circles, square: polar plots l,o,p. Scale, 5 µm, e, In vivo imaging/visual stimulation. f, Visually-evoked Ca++ signal in thalamocortical axon (top trace: photodiode signal; bottom trace: ΔF/F. g, Directional stimuli (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, 315°). h–j, Direction- (h,i) and orientation-tuned (j) varicosities. 5–8 trial average. k–s, Polar plots of F1 (red) or F2 (black) magnitude responses (Methods). Inner solid ring: average response to mean grey stimulus. Shaded: 3 standard deviations greater than the mean response to grey stimuli. Lower right of each plot: OSI/DSI . Upper right: Fourier amplitudes. t, DSI/OSI, all varicosities (5 mice, n= 58 varicosities). Mean ± s.e.m. u, Cumulative distributions: OSI (circles), DSI (squares).

Figure 5f shows an example of visually-evoked calcium transients in a thalamocortical axon. Figure 5h,i show two clear and striking examples of direction-tuned signals in dLGN axons located within superficial V1. The first example (Fig. 5h), responds only to gratings drifting at 45 degrees (polar plot Fig. 5k). The second example (Fig. 5i) is also direction selective but is more broadly tuned (polar plot Fig. 5l). Interestingly, we also observed thalamocortical axons that were strongly tuned not for direction, but instead for orientation (Fig. 5j and Fig. 5n–q). Overall, a variety of strengths of direction and orientation tuning were observed, including some thalamocortical axons that were not tuned for either feature (Fig. 5r,s). Approximately 60% of all thalamocortical axons imaged had direction selectivity indexes DSI ≥0.4, a commonly used threshold for categorizing mouse DSGCs21 and approximately ~85% had OSIs of ≥0.5 (Fig. 5t,u) (5 mice, n= 58 varicosities). Thus, the majority of visual information delivered to superficial V1 by neurons in the dLGN shell/DSGC-RZ is direction- and/or orientation-tuned.

Our results are the first to define a circuit relationship between DSGCs and visual cortex and they suggest that in the mouse direction-tuned and orientation-tuned V1 neurons may inherit their characteristic receptive field properties from DSGCs. Notably, such influence may be specific to neurons receiving thalamic excitation within superficial V1. Indeed, our results of trans-synaptic labeling of RGCs from V1 layer 4, combined with recent studies that recorded thalamic excitation in layer 4[ref: 22,23] suggest that orientation and direction selectivity of neurons in deeper V1 arises from the convergence of retinal and thalamic afferents with center-surround receptive fields, as opposed to direction- or orientation-tuned receptive fields.

Interestingly, we discovered that several different types of On-Off DSGCs as well as upward-tuned Off-DSGCs feed the retino-geniculo-superficial V1 circuit. We also found that some thalamocortical axons are tuned for specific axes of motion, whereas others are orientation-tuned24, 25. Thus, the tuning of V1 neurons that receive input from neurons in the shell/DSGC-RZ may reflect the integration of individual or multiple DSGC types, as well as intra-cortical circuitry26,27,28. Together, our findings suggest that directional motion encoded at the level of the retina may influence the direction and orientation selectivity of some V1 neurons.

Methods summary

All experimental protocols were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for animal research and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University California, San Diego.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

METHODS

All experimental protocols were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University California, San Diego.

Mice

Pigmented, wildtype, DRD4-GFP5, Trhr-GFP6 mice of both sexes (40 to 60 days old) were used. Animals from different litters and parent mice were used for each experiment. Sample sizes (number of mice and/or cells) for each experiment are stated in main text and figure legends.

Retrograde tracer injection

Mice were anesthetized using an isoflurane–oxygen mixture (4.0% (v/v) for induction and 1.5% (v/v) for maintenance) and given the analgesic buprenorphine (SC, 0.3 mg/kg). After a midline scalp incision, a small burr hole was made with a pneumatic dental drill (Henry Schein) over V1. For tracer injections into cortex we used either i) red fluorescent-latex beads (Lumafluor, Inc.) that travel strictly in retrograde fashion from axon terminals at the injection site to cell bodies of origin29, or ii) Cholera toxin beta (CTβ-594; Invitrogen) which travels both anterograde and retrograde. Tracers (200 nl volume) were injected with a Nanoject II (Drummond) through a small glass pipette (~0.5 MΩs). No distinguishable differences were observable in dLGN labeling patterns between the two retrograde tracers, except that full-depth injections with CTβ-594 also labeled L6 axons (e.g., Fig. 2a,b). All injections were targeted stereotaxically to V1 using the following coordinates: 0.2–0.5 mm anterior to Lambda and 2.5 mm lateral from midline. For superficial injections we penetrated the cortex to a final destination of 150 µm and for deep injections to a depth of 650 µm. Full-depth experiments were accomplished by injecting tracers at multiple cortical depths.

Virus injections

For injections of AAV2 expressing histone-tagged GFP and rabies glycoprotein (AAV2-Glyco-hGFP, titer, 1.0 × 1013 genomic titer/ml) into the dLGN a small burr hole was made using the following stereotaxic coordinates: 2.10 mm posterior to Bregma and 2.2 mm lateral from midline. A small glass pipette (~0.5 MΩ) was lowered 2.50 mm from the pial surface and using a Nanoject II (Drummond), 0.04–0.40 µls of virus was inoculated into the brain. A 3-week waiting period was introduced post- AAV2-Glyco-hGFP injection in order to allow maximal expression, after which the scalp was re-incised and a second burr hole was made over V1 for injections of ΔG-RABV-mCherry. It was crucial to inject AAV2-Glyco-hGFP before ΔG-RABV-mCherry because AAVs require more time for expression to occur. ΔG-RABV expressed within 5–7 days and only dLGN neurons expressing both the ΔG-RABV and Glyco-hGFP are competent to infect RGCs that synapse with them. For the cortical injections of ΔG-RABV-mCherry, a pipette (~0.5 MΩ) was lowered to a final destination of either 150 µm (‘superficial’) or 450 µm (‘deep’), and 0.04–0.40 µl of glycoprotein-deleted modified rabies virus encoding mCherry (ΔG-RABV-mCherry, titer, 8.0 × 108 − 2.0 × 109 infectious unit/ml) was inoculated. After surgeries the skin was sutured and the animals were allowed to recover in a heated chamber. For ΔG-RABV-mCherry infections, mice were housed in a biosafety room for 5–7 days to allow rabies virus to infect, trans-synaptically spread, and express mCherry in presynaptic cells.

Virus production

The coding sequence of Histone2B-tagged GFP and rabies virus glycoprotein B19G linked by the F2A element was amplified by PCR with high-fidelity Phusion polymerase8. CMV enhancer and synapsin promoter were cloned by PCR30. These PCR fragments were inserted into the AAV vector containing woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element. Every plasmid was sequenced before virus production. AAV were generated with transfection of HEK293t cells, purified by iodixanol gradient centrifugation and titered in HEK293t cells with qPCR. The titer of the AAV used in this study was 1.0 × 1013 genomic titer/ml[ref: 31]. ΔG-RABV expressing mCherry was amplified in B7GG cells, concentrated by two rounds of centrifugation, and titered in HEK293t cells as described previously8. The titers of the rabies viruses were 8.0 × 108 − 2.0 × 109 infectious unit/ml. The viruses were stored at −80°C until use.

Retinal histology

Five to seven days after ΔG-RABV-mCherry injection, whole-mount retinas were harvested and fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min-1 hour, then washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 3x, 30 min). The retinas were left for 2 hours in blocking solution (10% goat serum, 0.25 % Triton-X) at room temperature, then transferred to primary antibodies for 12–18 h at 4° C, and washed in PBS (3x, 30 min). The retinas were incubated in secondary antibody for 2 hours, and washed in PBS (3x, 30 min). Then, retinas were mounted and cover slipped with either Vectashield containing dapi (Vector Laboratories) or Prolong Gold with dapi (Invitrogen). Depending on the experiment, the following primary antibodies were used (1:1000 guinea pig anti-GFP, Synaptic Systems; 1:1000 rabbit anti-Cart, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 1:1000 mouse anti-SMI-32, Covance; and 1:1000 rabbit anti-DSRed, Clontech). The following secondary antibodies were used (1:1000 goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 488; 1:1000 goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647; 1:1000 goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594; 1:1000 goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488; Invitrogen).

Retinal physiology

Trhr-GFP mice (6–8 weeks old) were used for targeted recordings of GFP+ DSGCs using methods described previously32. GFP+ RGCs were identified using two-photon microscopy to minimize photopigment bleaching. Loose patch recording was used to measure spike responses to moving bar stimuli projected onto the photoreceptor layer from an OLED array (eMagin) with mean light levels of approximately 70 rhodopsin isomerizations/rod/sec and bar contrasts of 200–300%.

Brain histology

Following retrograde or trans-synaptic tracer injection, mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbitol and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% PFA. Brains were removed, fixed overnight in PFA and then transferred to a 30% (w/v) sucrose solution and stored at 4° C. Brain slices were collected at 40–60 µm thickness in the coronal plane using a sliding microtome. Brain sections containing dLGN and visual cortex were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in a blocking solution (10% goat serum, 0.25% Triton-X). This was followed by an overnight incubation with rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, Invitrogen) and guinea pig anti-VGLUT2 (1:1000, Milipore) primary antibodies in blocking solution at room temperature. Sections were then rinsed with PBS (3x, 30 minutes), and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit (1:1000, Invitrogen) and Alexa-Fluor 647 goat-anti guinea pig (1:1000, Invitrogen) secondary antibody. Lastly, sections were washed with PBS and mounted with Vectashield with dapi (Vector laboratories).

Targeted filling of genetically tagged RGCs

Targeted RGC filling was conducted using methods described previously33. Retinas from mice aged between P25–P30 mice were dissected and kept in an oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) solution of Ames' medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 23 mM NaHCO3. Borosilicate glass sharp electrodes were used to fill GFP+ RGCs with 10 mM solution of Alexa 555 hydrizide (Invitrogen) in 200 mM KCl, with the application of hyperpolarizing current pulses ranging between 0.1–0.9 nA for 5–20 minutes. After cell filling, the retinas were fixed for 1 hour with 4% PFA and were processed for immunocytochemistry using the methods described above. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, Invitrogen), guinea pig anti-VAChT (1:1000, Millipore), Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-guinea pig (1:1000, Invitrogen). Sections were rinsed with PBS and mounted with Prolong Gold with dapi (Invitrogen).

Confocal imaging

Fluorescence images were acquired on a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710 and 780) equipped with 405, 488, 561 and 633 nm laser lines. Image stacks with a scanning resolution of 1024×1024 pixels were collected using the following objective lenses: 10×/0.45 Plan-Apochromat (step size of 3.7–4.0 µm), 20×/0.8 Plan-Apochromat (step size of 1.0 µm) and LD C-Apochromat 40×/1.1 water immersion (step size of 0.5–1 µm).

Quantification

For calculating cortical intensity profiles for superficial and deep injections of tracers, the location of the injection was identified from epifluorescent images of tissue sections taken from the entire brain. We evaluated tracer spread along the length of the injection site (from pia to white matter) and the width (parallel to the pial surface). Background fluorescence was subtracted using the contralateral non-injected cortex as the baseline control. After background subtraction, the peak fluorescence along the injection site was quantified by dividing the site into equidistant areas along the injection height and width from pia to the white matter (~800–1000 µm). For each fluorescence intensity profile, the peak was identified as maximum fluorescence. The fluorescence signal was normalized to this value. Four to five intensity profiles were analyzed per tissue section. All tissue sections surrounding the injection site were included in the analysis. We confirmed superficial injections as those with peaks ≤ 150 µm from the pia and deeper injections as those with peaks > 300 µm from the pia.

For measuring the location of retrogradely labeled cells along the medial-lateral axis of dLGN, we obtained fluorescent confocal images (10× and 20×) of coronal brain tissue sections. The boundaries of the dLGN were identified using two stable features: the optic tract, which defines the lateral dLGN border, and the intralaminar zone between the dLGN and the latero-posterior nucleus, which defines the dLGN’s medial border. Four measurements were taken per tissue section from locations that spanned the entire rostral-caudal length of the dLGN and thus, the entire retinotopic map. These measurements were placed at equidistant points along the width of the dLGN and an average distance of each labeled cell along the axis from the optic tract (0%) to the medial border (100%) was obtained.

To quantify overlap between retrogradely infected dLGN relay neurons and GFP+ DSGC axons we obtained fluorescent confocal stacks of coronal tissue sections through the dLGN. For the GFP channel a median filter (2 pixels) was applied and then background subtracted using a rolling ball radius algorithm (50 pixels). After processing images, maximum intensity projections were generated for both channels and the GFP channel was subsequently thresholded using a triangular algorithm34. The thresholded image was then binarized to create a mask representing the complete area populated by GFP+ DSGC axons. This mask was superimposed on the red channel. Every mCherry+ cell body was identified and its location assessed for overlap with the DSGC-RZ. We note that modified rabies viruses may underestimate total numbers of presynaptic inputs to double-infected cells.

To determine the area of contact between dLGN neurons and VGLUT2 containing DSCC axons, , we quantified the percentage of the total somatodendritic area of the mCherry expressing neuron that co-localized with GFP signal from the genetically tagged On-Off DSGC, and that were also immunoreactive for VGLUT2. First, GFP and VGLUT2 puncta were identified by a series of filtering (median= 2 pixels) and erosion steps. This image was then thresholded to identify regions of interest (ROIs) that contained VLGUT2 and GFP puncta, and this was divided by the total measurement of the mCherry labeled area. Images were processed and analyzed using algorithms in ImageJ (NIH).

For retinal co-localization experiments, the maximum intensity projections for confocal stacks were obtained for red (mCherry), green (GFP) and far-red channel (Cart). Confocal sections were background subtracted and a maximum projection of the stack was obtained. Channels were merged and markers were considered co-localized if signals from different channels coincided within the same plane.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of fluorescent intensity profiles, normalized distances across the cortex and dLGN and axonal overlap of labeled relay cells and axons was carried out using custom routines in MATLAB (Mathworks) and Image-J (NIH). All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software), and represented as averages. Error bars in graphs represent the s.e.m., where n= number of cells and N= number of mice. P-value of < 0.05 was used to determine significance. All statistical tests were judged as appropriate and described throughout the manuscript. P-values for post hoc tests involving multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Tukey’s method. No randomization method was used to assign mice to the experimental groups and investigators were blinded to the original group allocation or when assessing an outcome. Variance and normality were tested to ensure that a suitable statistical test was chosen. The variance was similar between groups that were statistically compared. Normality testing in groups with a small number of samples was done with quantile-quantile plots.

For anatomical tracing experiments samples sizes were determined based on preliminary experiments that tested the labeling/infection efficiency of retrograde tracers and/or viral trans-synaptic tools. For imaging experiments no statistical test was used to determine sample size a priori. Experiments were included in the study if they were deemed successful. For the trans-synaptic studies, the experiment was discarded if there were no rabies infected RGCs as assessed by fluorescence. For experiments involving two-photon imaging of axons, data belonging to non-visually responsive axons was not included in the experiment. In addition, mice in which we found no visually driven axons were also excluded from the study.

Imaging of visually evoked calcium signals in DSGC-RZ thalamocortical axons

For monitoring the activity of dLGN axons in V1 either the slow (GCaMP6S, titer, 3.04 × 1013 genomic titer/ml) or the fast (GCaMP6F, titer, 2.96 × 1013 genomic titer/ml) version of the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6 (AAV1.Syn.GCaMP6.WPRE.SV40)[ref: 20] were injected into the dLGN using the following coordinates: 2.10 mm posterior to Bregma and 2.2 mm lateral from midline. A small glass pipette (~0.5 MΩ) was then lowered 2.30 mm from the pial surface and using a Nanoject II (Drummond) 0.04–0.20 µls of virus was inoculated into the brain.

Three weeks after the injection of the calcium indicator, mice were deeply anesthetized using an isoflurane–oxygen mixture (4% (v/v) for induction and 1.5% (v/v) for maintenance) and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Following midline incision, a 2 mm diameter craniotomy (1 mm anterior to lambda, 2.5 mm lateral to midline) was performed in the left contralateral primary visual cortex of adult (two month old) C57/Bl6 mice. Next, a sterile 3 mm glass coverslip was gently laid over the dura mater (without using agarose) and glued to the skull with cyanoacrylate glue. Black dental acrylic (Lang Dental) was then applied throughout the skull surface up to the edges of the coverslip and the skin. A custom-made titanium chamber (diameter: 16 mm, thickness: 1.3 mm) was also embedded in the dental acrylic to help secure the mouse onto the stage of the microscope and shield the microscope objective and the photomultipliers from stray light.

Image acquisition and presentation of stimulus grating

Mice were transferred and head-fixed to a stage while under isoflurane anesthesia and kept at 37° C using a temperature control device (Harvard Apparatus). Anesthesia was maintained at 0.8–1.0% (v/v). Imaging was performed using a two-photon microscope system (Sutter) controlled by ScanImage software35 written in MATLAB (MathWorks). Excitation light from a Mai Tai DeepSee laser (Newport Corp.) with group delay dispersion compensation was scanned by galvanometers (Cambridge Technologies). Images were collected through a 20x objective (1.0, N.A., Olympus) and the laser power was typically maintained well below 50 mW at the sample. GCaMP6 was excited at 910nm and emission was collected with a green filter (535 nm center; 50 nm band; Chroma) via photomultiplier tubes (PMT) (H7422PA-40, Hamamatsu Photonics). Images were collected (3x, digital zoom) at 8 HZ (256× 128pixels) or 16 HZ (256× 64 pixels). For each experiment the optical axis was adjusted to be perpendicular to the cranial window. Imaging was stopped between trials and during this time slow drifts in the optical focus were corrected using a template image. Bleaching of GCaMP6 was not evident during experiments. Because of the limitation of current genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors36 our experiments were not sensitive enough to detect single action potentials, and thus, biased to sample from axons with a high spiking probability.

A Visual stimulus containing a full-field 2-D moving grating or bar was generated using Psychtoolbox37,38 in Matlab version 2009. The monitor screen was positioned approximately parallel to, and 29 cm from the right eye of the mouse. The visual angle subtended by the monitor (±35° azimuth × ±23.5° elevation) ensured that projective distortions were small. Both drifting sinusoidal gratings and square wave gratings were used. For sinusoidal gratings, each presentation of a grating started with a grey screen for 3s, followed by the drifting gratings (0.02 CPD, 2 Hz, 3 s). In the case of square wave gratings, each trial started with a gray screen for 3s, followed by the drifting bars (0.01 CPD, 0.33 Hz, 12.75 s). Each trial consisted of presenting eight gratings of different orientations. Within a trial, the orientation of the grating was randomly interleaved. Five to eight trials were recorded to measure average axonal responses to different orientations. Simultaneously, we captured the on-screen luminance by recording the output of a photodiode (Thorlabs) placed at the corner of the screen.

Analysis of time-lapse images and visually evoked fluorescent responses

Frames from time-lapse imaging were registered using template matching (normalized correlation coefficient) and alignment plugins coded in ImageJ (NIH; https://sites.google.com/site/qingzongtseng/template-matching-ij-plugin). To align images we first generated an average image from a small number of frames within a trial where there was minimal movement. A region of interest (ROI) was then selected within this average template image and was used to register all the frames within that repetition.

To extract fluorescence signals, ROIs were drawn over GCaMP6+ varicosities identified by using the mean intensity and standard deviation values of all the repetitions. The pixels in each ROI were averaged to estimate fluorescence corresponding to a single varicosity. Calcium signals were expressed as relative fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0 = ((F − F0)/F0)) corresponding to the mean fluorescence from all pixels within specified ROIs.

For each experiment, stimulus temporal frequency was measured using the photodiode signal. Putative visually responsive axons were chosen and the calcium signals’ response power at the stimulus frequency (F1) and response power at twice stimulus frequency (F2) were measured. To gauge if the measured power was significant, we compared each visually-evoked response power with the mean (µgrey) and the standard deviation (σgrey) of calcium response powers to the grey stimulus that immediately preceded each grating. Axons were deemed visually responsive, and included for further analysis, if the F1 power of the visually-evoked calcium signal was greater than µgrey + 3σgrey for at least two of the orientations probed. Most (4 out of 5 mice) of the calcium imaging experiments were done using GCaMP6S. For the experiment where we used GCaMP6F we were able to measure frequency doubling responses to the stimulus presentation. Axons were classified as ‘linear’ if at the orientation corresponding to peak F1 power, the F2 power was smaller than the F1 power. If the F2 power was greater, the axon was judged as ‘non-linear’. In experiments where we used GCaMP6F in combination with lower temporal frequency drifting grating stimulus, we observed two GCaMP6+ varicosities with On-Off responses (Fig. 5i and corresponding polar plot 5l, and polar plot in Fig. 5q; and see imaging methods above). We did not observe differences in the percentage of varicosities that were visually responsive using GCaMP6S compared to GCaMP6F (data not shown); therefore both sets of data are grouped in Fig. 5t, u. Power calculation was performed using the chronux package (mtspectrumc with default tapers; see http://chronux.org/ [ref:39]. Tuning properties with regard to the orientation of the gratings were quantified by calculating a selectivity index (OSI/DSI). The OSI was defined as (Rpref − Rortho)/(Rpref + Rortho), where Rpref, the response in the preferred orientation, was the fluorescent response with the peak F1 power. Rortho was similarly calculated as the response evoked by the orthogonal orientation. DSI was defined as (Rpref − Ropp)/(Rpref + Ropp), where Ropp is the response in the direction opposite to the preferred direction. Direction tuned neurons were defined as neurons with a selectivity index ≥ 0.4 and orientation selective neurons were defined as those with an index ≥ 0.5.

Extended Data

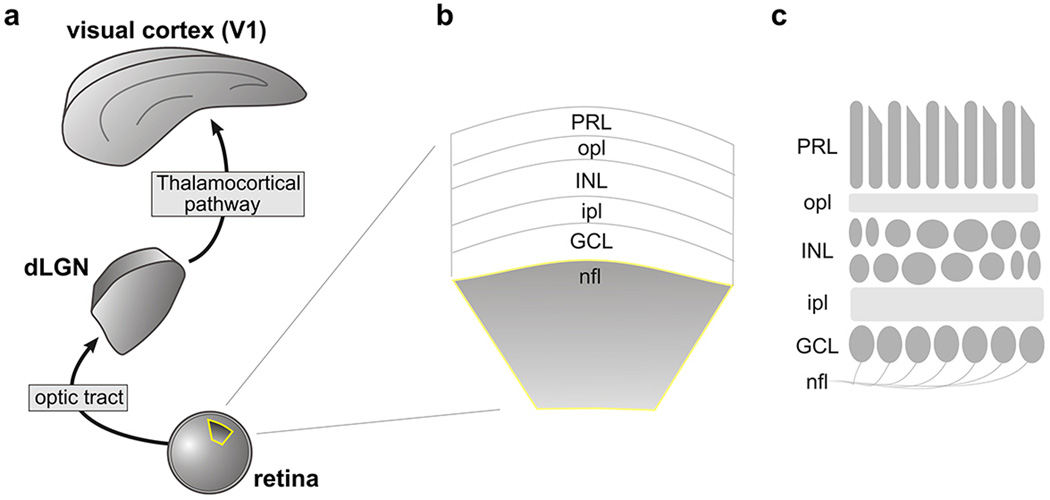

Extended Data Figure 1. The retino-geniculo-cortical pathway links retinal cells and circuits, to the brain.

a, Diagram of retina, dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) and primary visual cortex (V1). The optic tract which carries retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons and thalamocortical (dLGN to V1) pathway also shown. b, Diagram of retinal layers: PRL, photoreceptor layer; opl, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; nfl, nerve fiber layer. c, Retina diagram with cells shown (labels same as in b).

Extended Data Figure 2. Approach for assessing laminar specificity of mouse geniculocortical projections.

a, Focal retrograde tracer injection to V1. Scale, 3 mm. b, Diagram of the three different injection depths used to generate data in Fig. 2. c, Percentage of fluorescence in V1 from superficial (black line) versus deep (gray line) injections. Superficial: peak intensity occurs at 25 μm from pial surface (4 mice). Deep: peak intensity occurs at 350 μm from pial surface. Gray shaded regions: s.e.m. (superficial vs. deep= ***P < 0.0001; two-way ANOVA). d, Assessment of retrogradely labeled cells across the width of the dLGN. 0% is at optic tract, 100% is at medial border (see Fig. 2g–i).

Extended Data Figure 3. Retrograde tracers to superficial V1 label cells in the DSGC-RZ.

a–c, Same dLGN as in main Fig. 2f but with GFP+ On-Off DSGC6 axons shown. a, most of the retrogradely labeled cells (magenta/dashed circles) reside in the DSGC-RZ (green terminals). Asterisk: labeled cell outside the DSGC-RZ. Scale, 200 μm b,c, High magnification views of retrogradely labeled dLGN neuron cell bodies with potential contact from GFP+ DSGC axons (arrow in b); c, this cell is in vicinity of DGSC axonal boutons (arrowheads). b,c, Scale, 15 μm. d, Diagram of laminar specific connections between DSGC-RZ and superficial V1 and dLGN core and deeper V1 layers 4 and 6.

Extended Data Figure 4. Analysis of dLGN neurons retrogradely infected from superficial V1.

a–f, Example serial sections of anterior, middle and posterior portions of dLGN in a mouse with GFP expressing On-Off DSGC axons that was injected with ΔG-RABV-mCherry in superficial layers of V1. a, dapi to show cytoarchitectural landmarks and dLGN borders. b, GFP+ DSGC axons and AAV-Glyco-hGFP infected cell bodies (see main Fig. 4 and text). c, Mask of GFP+ DSGC axons (Methods). d, ΔG-RABV-mCherry+ dLGN relay neurons. e, GFP+ DSGC axon mask superimposed with mCherry signal; this was used to determine colocalization. f, mCherry and hGFP signals merged. Scale, 200 μm.

Extended Data Figure 5. Putative sites of contact between DSGC axons and a dLGN neuron retrogradely infected from superficial V1.

a–i, GFP+ On-Off DSGC axons (green in all panels except black in b) and mCherry+ dLGN relay neuron (magenta in all panels except white in c) infected by injection to superficial V1. Framed region in a is shown at higher magnification in b–d. Arrowhead (a): thalamocortical axon of mCherry+ dLGN cell. Scale in a, 50 µm. Yellow boxed region in c,d, is shown at higher magnification in e–i. Scale in d, 15 µm. e–i, Some DSGC axon-dendrite contacts contain VGLUT2 (blue). f–i, arrowhead: site of GFP/mCherry co-localization that does not contain VGLUT2. Arrow: GFP/mCherry/VGLUT2+ contact.

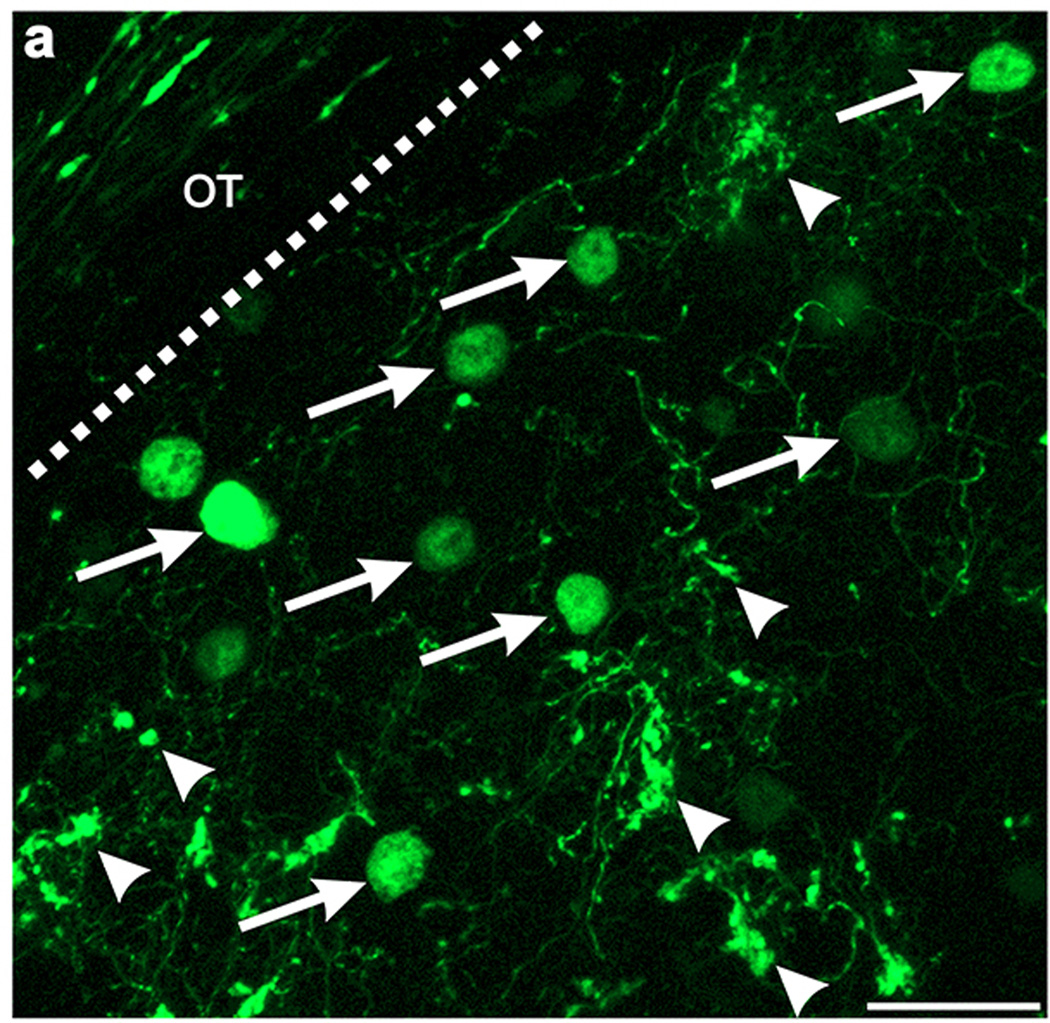

Extended Data Figure 6. The axons of GFP+ On-Off DSGCs and dLGN neurons infected with AAV2-Glyco-hGFP can be distinguished on the basis of their cellular localization.

High magnification view of DSGC-RZ in mouse with GFP + posterior-tuned On-Off DSGCs that was injected 14 days prior with AAV2-Glyco-hGFP. Glyco-hGFP+ neurons have nuclear GFP labeling (arrows) whereas DSGCs have GFP in axon terminals (arrowheads). Scale, 50 μm.

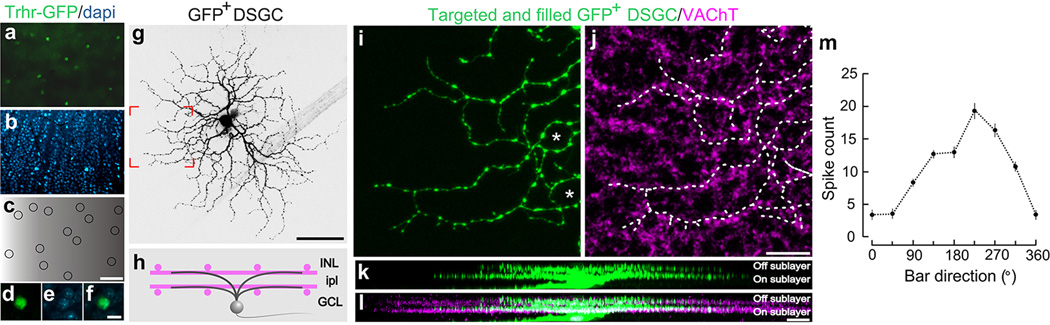

Extended Data Figure 7. Signature anatomical and physiological characteristics of GFP tagged On-Off DSGCs.

Flat mount retina with a, GFP+ On-Off DSGCs. b, co-stained with dapi. c, Positions of GFP+ RGCs. Scale in c, 150 µm. d–f, High magnification views. Scale, 12 µm. g, Targeted fill of a GFP+ DSGC. Scale, 50 µm. h, Schematic of On-Off DSGC stratification and starburst amacrine cells (magenta). Labeling as in Extended Fig. 1. i,j, Higher magnification of framed region in g stained for VAChT (starburst amacrine processes). Asterisk: ‘looping arborizations’. Dashed line: GFP arbor, which matches VAChT plexus. Scale, 10 µm. k,l, Side (x-z plane) views of cell in (g). GFP+ dendrites co-stratify with both the On and Off sublayers. Scale, 5 µm. m, Direction-tuned response of a GFP+ On-Off DSGC targeted for recording and receptive field characterization. The spike count is highest for bars moving toward ~270° in the cardinal axes.

Extended Data Figure 8. Injections of ΔG-RABV-mCherry into both superficial and deep V1 combined with AAV-Glyco-hGFP infection of dLGN core.

a, mCherry+ neurons in the DSGC-RZ and the core of the dLGN. b, AAV2-Glyco-hGFP: many neurons throughout the dLGN, but mostly along the medial border and not in the shell/DSGC-RZ express Glyco-hGFP. DSGC-RZ marked by axons of GFP+ On-Off DSGCs. c, Merged of a,b. Scale in a, 100 µm. Boxed regions with arrows: two dLGN neurons; both RABV-mCherry+ and AAV2-Glyco-hGFP+. One or both of these cells infected their presynaptic partner, the RGC shown in Figure 4 (panels cc-ee) of the main text. Scale, 15µm.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kleinfeld lab for helpful advice, and Fred Rieke and Max Turner for example DSGC recording, and the Salk Viral Vector and Biophotonics staff. This work was supported by Vision Core P30 EY019005, the Knights Templar Eye Foundation (O.S.D), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (F.O.), Kanae Foundation (F.O.), Uehara Memorial Foundation (F.O.), Naito Foundation (F.O.), NINDS Circuits Training Grant (R.N.E.), Gatsby Charitable Trusts (E.M.C and A.G), NIH EY022577 and MH063912 (E.M.C.), Whitehall Foundation (A.D.H), Ziegler Foundation for the Blind (A.D.H), Pew Charitable Trusts (A.D.H), The McKnight Foundation (A.D.H), and NIH R01EY022157-01 (A.D.H).

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.D.H, A.C-M., A.G., and R.N.E-D. designed the experiments. A.D.H., A.C-M., R.N.E-D. and P.L.N. carried out and analyzed the circuit connectivity experiments. A.C-M. carried out the in vivo imaging experiments. B.S. and A.C-M analyzed imaging data. O.S.D. collected data on molecular markers of cell types. E.M.C. and F.O. designed and made the rabies viruses. A.D.H. and A.C-M. wrote the paper in collaboration with the other authors. A.D.H. and A.C-M. prepared the figures. A.D.H. oversaw the project.

The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Barlow H, Hill R. Selective sensitivity to direction of movement in ganglion cells of the rabbit retina. Science. 1963;139:412–414. doi: 10.1126/science.139.3553.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briggman KL, Helmstaedter M, Denk W. Wiring specificity in the direction-selectivity circuit of the retina. Nature. 2011;471:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature09818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei W, Feller MB. Organization and development of direction-selective circuits in the retina. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim IJ, Zhang Y, Yamagata M, Meister M, Sanes JR. Molecular identification of a retinal cell type that responds to upward motion. Nature. 2008;452:478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature06739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huberman AD, Wei W, Elstrott J, Stafford BK, Feller MB, Barres BA. Genetic identification of an On-Off direction-selective retinal ganglion cell subtype reveals a layer-specific subcortical map of posterior motion. Neuron. 2009;62:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivlin-Etzion M, Zhou K, Wei W, Elstrott J, Nguyen PL, Barres BA, Huberman AD, Feller MB. Transgenic mice reveal unexpected diversity of on-off direction-selective retinal ganglion cell subtypes and brain structures involved in motion processing. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:8760–8769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0564-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wickersham IR, Lyon DC, Barnard RJ, Mori T, Finke S, Conzelmann KK, Young JA, Callaway EM. Monosynaptic restriction of transsynaptic tracing from single, genetically targeted neurons. Neuron. 2007b;53:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osakada F, Mori T, Cetin AH, Marshel JH, Virgen B, Callaway EM. New rabies virus variants for monitoring and manipulating activity and gene expression in defined neural circuits. Neuron. 2011;71:617–631. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalupa LM, Werner JS. The Visual Neurosciences. MIT Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krahe TE, El-Danaf RN, Dilger EK, Henderson SC, Guido W. Morphologically distinct classes of relay cells exhibit regional preferences in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the mouse. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:17437–17448. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4370-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grubb MS, Thompson ID. Biochemical and anatomical subdivision of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in normal mice and in mice lacking the beta2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Vision Res. 2004;44:3365–3376. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin LP, Blanchard JH. Forebrain connections of the hamster intergeniculate leaflet: comparison with those of ventral lateral geniculate nucleus and retina. Vis. Neurosci. 1999;16:1037–1054. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899166069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafols JA, Valverde F. The structure of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the mouse. A Golgi and electron microscopic study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1973;150:303–32. doi: 10.1002/cne.901500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Land PW, Kyonka E, Shamalla-Hannah L. Vesicular glutamate transporters in the lateral geniculate nucleus: expression of VGLUT2 by retinal terminals. Brain Res. 2004;996:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay JN, De la Huerta I, Kim IJ, Zhang Y, Yamagata M, Chu MW, Meister M, Sanes JR. Retinal ganglion cells with distinct directional preferences differ in molecular identity, structure, and central projections. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:7753–7762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0907-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhande OS, Estevez ME, Quattrochi LE, El-Danaf RN, Nguyen PL, Berson DM, Huberman AD. Genetic dissection of retinal inputs to brainstem nuclei controlling image stabilization. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:17797–813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2778-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C, Regehr WG. Developmental remodeling of the retinogeniculate synapse. Neuron. 2000;28:955–66. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huberman AD, Manu M, Koch SM, Susman MW, Lutz AB, Ullian EM, Baccus SA, Barres BA. Architecture and activity-mediated refinement of axonal projections from a mosaic of genetically identified retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2008;59:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volgyi B, Abrams J, Paul DL, Bloomfield SA. Morphology and tracer coupling patterns of alpha ganglion cells in the mouse retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;492:66–77. doi: 10.1002/cne.20700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svododa K, Kim DS. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivlin-Etzion M, Wei W, Feller MB. Visual stimulation reverses the directional preference of direction-selective retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2012;76:518–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YT, Ibrahim LA, Liu BH, Zhang LI, Tao HW. Linear transformation of thalamocortical input by intracortical excitation. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1324–30. doi: 10.1038/nn.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lien AD, Scanziani M. Tuned thalamic excitation is amplified by visual cortical circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1315–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshel JH, Kaye AP, Nauhaus I, Callaway EM. Anterior-posterior direction opponency in the superficial mouse lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuron. 2012;76:713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piscopo DM, El-Danaf RN, Huberman AD, Niell CM. Diverse visual features encoded in mouse lateral geniculate nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:4642–4656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5187-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livingstone MS. Mechanisms of direction selectivity in macaque V1. Neuron. 1998;20:509–526. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atallah BV, Bruns W, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Parvalbumin-expressing interneurons linearly transform cortical responses to visual stimuli. Neuron. 2012;73:159–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SH, Kwan AC, Zhang S, Phoumthipphavong V, Flannery JG, Masmanidis SC, Taniguchi H, Huang ZJ, Zhang F, Boyden ES, Deisseroth K, Dan Y. Activation of specific interneurons improves feature selectivity and visual perception. Nature. 2012;488:379–83. doi: 10.1038/nature11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz LC, Burkhalter A, Dreyer WJ. Fluorescent latex microspheres as a retrograde neuronal marker for in vivo and in vitro studies of visual cortex. Nature. 1984;310:498–500. doi: 10.1038/310498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hioki H, Kameda H, Nakmura H, Okunomiya T, Ohira K, Nakamura K, Kuroda M, Furuta T, Kaneko T. Efficient gene transduction of neurons by lentivirus with enhanced neuron-specific promoters. Gene Ther. 2007;14:872–882. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osakada F, Callaway EM. Design and generation of recombinant rabies virus vectors. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1583–601. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy GJ, Rieke F. Network variability limits stimulus-evoked spike timing precision in retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2006;52:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beier KT, Borghuis BG, El-Danaf RN, Huberman AD, Demb JB, Cepko CL. Transynaptic tracing with vesicular stomatitis virus reveals novel retinal circuitry. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:35–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0245-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zack GW, Rogers WE, Latt SA. Automatic measurement of sister chromatid exchange frequency. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1977;25:741–753. doi: 10.1177/25.7.70454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pologruto TA, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. ScanImage: flexible software for operating laser scanning microscopes. Biomed. Eng. Online. 2003;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, Bargmann CI, Jayaraman V, Svoboda K, Looger LL. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP indicators. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:875–81. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brainard DH. The psychophysics toolbox. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spatial Vision. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bokil H, Andrews P, Kulkarni JE, Mehta S, Mitra PP. Chronux: a platform for analyzing neural signals. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2010;192:146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]