Abstract

Objective

Cancer risk behaviors often begin in adolescence and persist through adulthood. Tobacco use, indoor tanning, and physical inactivity are highly prevalent, socially patterned cancer risk behaviors, and their prevalence differs strongly by sex. It is therefore possible that these behaviors also differ by gender expression within the sexes due to social patterning.

Methods

We examined whether 5 cancer risk behaviors differed by childhood gender expression within the sexes and whether patterns of media engagement (e.g., magazine readership and trying to look like media personalities) explained possible differences, in a US population-based cohort (N=9,435).

Results

The most feminine girls had higher prevalence of indoor tanning (prevalence risk ratio (pRR)=1.32, 95% CI=1.23, 1.42) and physical inactivity (pRR=1.16, 95% CI=1.01, 1.34) and lower prevalence of worse smoking trajectory (prevalence odds ratio (pOR)=0.75, 95% CI=0.65, 0.88) and smoking cigars (pRR=0.61, 95% CI=0.47, 0.79) compared with least-feminine girls. Media engagement accounted for part of the higher prevalence of indoor tanning. The most masculine boys were more likely to chew tobacco (pRR=1.78, 95% CI=1.14, 2.79) and smoke cigars (pRR=1.55, 95% CI=1.17, 2.06), but less likely to follow a worse smoking trajectory (pOR=0.69, 95% CI=0.55, 0.87) and be physically inactive (pRR=0.54, 95% CI=0.43, 0.69) compared with least-masculine boys.

Conclusions

We found some strong differences in patterns of cancer risk behaviors by gender expression within the sexes. Prevention efforts that challenge the “masculinity” of smoking cigarettes and cigars and chewing tobacco and challenge the “femininity” of indoor tanning to reduce their appeal to adolescents should be explored.

Keywords: masculinity, femininity, cigarette smoking, cigar smoking, chewing tobacco, physical activity, tanning, cancer

Introduction

Tobacco use, indoor tanning, and physical inactivity are risk behaviors for cancer that are highly prevalent among US adolescents and young adults. These risk behaviors differ strongly by sex. Nationally, substantially more young men than young women smoke: 28% of men versus 16% of women ages 18-24 years are current smokers[1]. Use of chewing tobacco and cigar smoking are also more prevalent in males[2], while indoor tanning[3] and physical inactivity are more prevalent in females[4-6].

Sex differences in socially influenced risk behaviors are likely to in part reflect underlying gender processes, processes that may also lead to differences in risk behaviors by gender expression within the sexes. Research in this emerging area has found differences by gender expression in disordered eating[7, 8], body-shape concerns[9] and problem drinking[8]. However, it is unknown whether differences in cancer risk behaviors by gender expression exist within the sexes, in other words, whether masculine versus feminine boys have higher prevalence of risk behaviors more common in males and whether feminine versus masculine girls have higher prevalence of risk behaviors more common in females. Children who do not conform to the norms for their biological sex in terms of style of play, appearance and friendships may be less likely to adopt risk behaviors typical for their sex. Similarly, children who do not conform to gender norms for their sex may be more likely to adopt risk behaviors more typical of the other sex, compared with gender-conforming children.

Media may play an important role in the perception of certain cancer risk behaviors as masculine or feminine. For example, in the past decade magazine advertisements for chewing tobacco have targeted males and have succeeded in increasing chewing tobacco use among men[10]. Similarly, indoor tanning advertisements are targeted at adolescent girls and young women, purporting to improve sexual appeal, attractiveness, fitness, and mood[11]. Media exposure has been associated with adoption of cancer risk behaviors in adolescents[12-15]. Therefore, exposure to media may partly explain associations between childhood gender expression and cancer risk behaviors. Better understanding of differences in cancer risk behaviors within sexes by gender expression and the role media may play in creating these differences could improve the content and targeting of prevention efforts. However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the prevalence of cancer risk behaviors in adolescence and young adults by gender expression in childhood, nor have they examined the role of media use in possible differences in prevalence of cancer risk behaviors by gender expression.

In the present study, we assess the relationship between childhood gender expression and five cancer risk behaviors across adolescence and early adulthood in the Growing Up Today Study, a longitudinal cohort of adolescents followed into adulthood. We examine risk behaviors in three domains: physical inactivity, indoor tanning, and tobacco use, including cigarette, cigar and chewing tobacco use. Furthermore, we explore the contribution of media use to possible behavior differences.

We hypothesize that the most masculine boys will be more likely to engage in behaviors more prevalent among males, including cigarette, cigar, and chewing tobacco use, and will be less likely to engage in behaviors more prevalent among females, including physical inactivity and indoor tanning, compared with the least masculine boys. Similarly, we hypothesize that the most feminine girls will be more likely to engage in behaviors more prevalent among females, including physical inactivity and indoor tanning, and less likely to engage in behaviors more prevalent among males, including cigarette, cigar and chewing tobacco use, compared with the least feminine girls. We hypothesize that different patterns of involvement with media during adolescence by gender expression will partly account for these differences.

Methods

Sample

The Growing Up Today Study is an ongoing US longitudinal study of children of participants of the Nurses' Health Study II, enrolled in 1996 at ages 9 to 14 years and followed annually or biennially. Participants who responded to questions about their childhood gender expression in the 2005 or 2007 waves (collected, respectively, in 2005-2007 and 2007-2009) and who responded to items assessing cancer risk behaviors in any wave were included in our analyses. This research was approved by the Brigham and Women's Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Measures

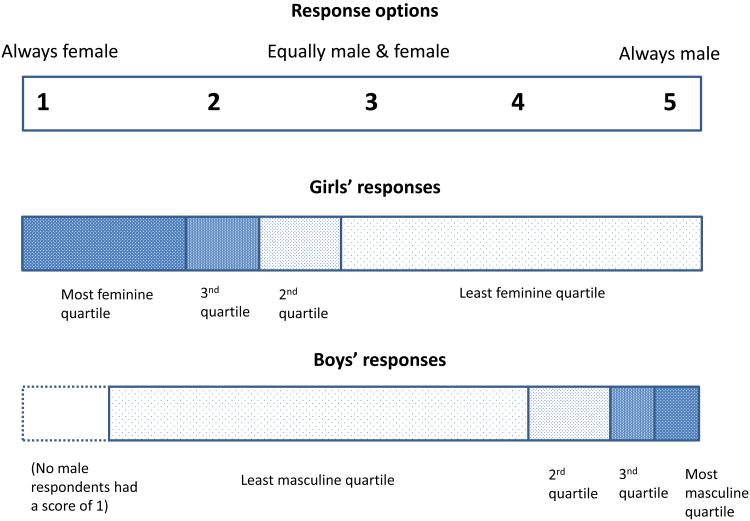

Childhood gender expression before age 11 years was assessed in the 2005 wave with 4 questions from the Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire[16] querying roles taken in pretend play, characters on TV admired or imitated, favorite toys and games, and feelings of masculinity and femininity. In a validation study, the complete measure had excellent discriminant validity by sex, sexual orientation, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and gender identity disorder[16]. Querying gender expression before age 11 years meant that, for most participants, we assessed gender expression occurring before the first risk behaviors were measured. Response options ranged on a five-point scale from “always women or girls/very ‘feminine’” to “always boys or men/‘very masculine.’” A gender-expression score was created by taking the mean of responses (Cronbach's alpha=0.78). The score was then divided into approximate quartiles, separately for males and females: from least masculine (reference group for males) or least feminine (reference group for females) to most masculine or feminine (Figure 1)[17-19].

Figure 1. Childhood gender expression, range of mean response by gender expression group and sex (N= 9,435).

Four cigarette smoking trajectories incorporating age of onset, age of cessation and number of cigarettes smoked per week at each age, occurring from ages 12 to 23 years were determined using general growth mixture modeling. Because patterns of smoking trajectories were similar for males and females, an unconditional model with both genders was used to estimate trajectories. Models with two through six class solutions were estimated to determine the optimal number of classes that best fit the data. The best-fitting model comprised four trajectories, which were, in order of lowest to highest risk: nonsmoker, experimenter, late initiator leading to moderate consumption, and early initiator leading to high consumption. Participants were assigned to the trajectory group for which they had the highest posterior probability of membership.[20, 21] We refer to the trajectory of early initiation leading to high consumption as the “worst” trajectory and consider each higher-risk trajectory “worse” than lower-risk trajectories (e.g., “experimenter” is worse than “nonsmoker”; “late initiator leading to moderate consumption” is worse than “experimenter” or “nonsmoker”). Past-year chewing tobacco use was queried in the 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2001 waves and was coded as any or none. Past-year cigar smoking was queried in 2001 and was coded as any or none.

Participation in 14 to 16 sports (e.g., swimming, soccer, weight training) was reported in 6 waves from 1996 to 2007. Time spent in moderate or vigorous exercise (hours/week) was calculated at each wave from these responses. Respondents who spent less than 1 hour/week of moderate or vigorous exercise were considered physically inactive for that wave. Indoor tanning was measured in five waves from 1999 to 2009. Participants were asked, “During the past year, how many times did you use a tanning booth or tanning salon?” Responses were coded as any or none.

Magazine preference was asked in the 1997, 1998 and 1999 waves with the question, “Which one type of magazine do you read most frequently?” Response options were: don't regularly read magazines, music, fashion, men's, humor, sports, gossip/celebrities, news, teen, health/fitness, TV/movies, women's, science, other. As some responses were rare, magazine preferences were grouped as: don't read magazines; music/television/gossip; sports; teen/fashion/men's/women's; health/fitness; and other. Trying to look like people in the media was queried in 6 waves from 1996 to 2003. Participants were asked “In the past year, how much have you tried to look like the girls or women (for girls; ‘boys or men’ for boys) you see on television, in movies or in magazines?” Five response options ranged from “not at all” to “totally.”

Included participants compared with those excluded were more likely to be female (63.7% versus 40.7%) and somewhat less likely to smoke cigars (12.8% versus 14.8% in 2001) and follow the worst smoking trajectory (15.2% versus 16.9%; all P-values <0.05). Included participants were similar to excluded participants in terms of age (included mean=11.6 versus 11.5 years in 1996), race/ethnicity (6.9% versus 7.2% nonwhite), chewing tobacco use (1.3% versus 2.7% in 1996), tanning indoors (9.2% versus 9.1% in 1996), and physical inactivity (0.7% versus 0.6% in 1996; all P-values>0.05).

Analysis

We examined patterns of cancer risk behaviors and media consumption by childhood gender expression. As 2001 was the only wave in which all risk behaviors were measured together, we used data from that wave to examine patterns of these behaviors by gender expression. To examine patterns of media engagement by gender expression, we used data from the first waves in which media engagement was queried, the 1996 and 1997 waves.

Next, to ascertain the risk of engaging in each behavior across all waves by gender expression, we created separate models with each behavior as the dependent variable. To examine the extent to which media engagement accounted for possible differences in risk behaviors, we further adjusted models for past-year magazine preference and trying to look like people in the media, updated annually as available. We then calculated the mediation proportion for media engagement, that is, the extent to which engagement with media accounted for possible gender-expression differences in cancer risk behaviors[22, 23]. If media engagement were a pathway by which gender-expression differences in cancer risk behaviors emerged, we would expect that adjusting for media engagement would attenuate the association between gender expression and the risk behavior. For these analyses chewing tobacco, physical inactivity and tanning were time-varying outcomes. As cigar smoking was measured once and cigarette smoking was categorized as one of four trajectories across adolescence, these two outcomes were time-invariant.

As some mothers enrolled more than one child in the Growing Up Today Study and to account for repeated measures of the risk behaviors, we used generalized estimating equations with a Poisson distribution and a log link to estimate prevalence risk ratios (pRR) for chewing tobacco use, cigar smoking, indoor tanning, and physical inactivity[24]. As smoking trajectory was an ordinal variable in four levels, to estimate prevalence odds ratios (pOR) of a worse smoking trajectory, we used ordered logistic regression with a cumulative logit link and a multinomial distribution. All models adjusted for age and race/ethnicity (white/nonwhite) and were stratified by sex.

Results

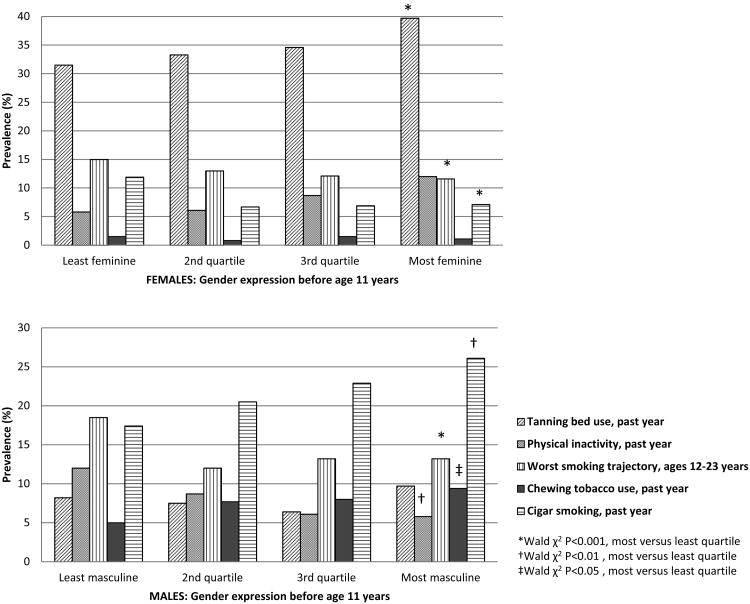

Participants were ages 9-15 years at the first wave of data collection and 19-27 years at the last included wave. Participants comprised 6010 females and 3425 males and were 93.1% white. Examining covariate-unadjusted prevalences, more females in the highest quartile of femininity tanned indoors, fewer smoked cigars, and fewer followed the worst smoking trajectory (i.e., early initiation leading to high consumption) than females in the lowest quartile of femininity (Figure 2). More males in the highest quartile of masculinity chewed tobacco and smoked cigars and fewer were physically inactive or followed the worst smoking trajectory compared with males in the lowest quartile of masculinity. Differences by gender expression in prevalence of tanning among males and physical inactivity and chewing tobacco use among females were not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Cancer risk behaviors by childhood gender expression and sex, 2001 (N= 9,435).

Magazine reading and trying to look like people on TV and in the movies differed by childhood gender expression (Table 1). Feminine girls were more likely to read teen/fashion magazines and less likely to read sports magazines than girls in the lowest quartile of femininity. Least-feminine girls were more likely to respond that they did not read magazines than most-feminine girls. Masculine boys were more likely to read sports magazines and less likely to read music/TV/gossip or other magazines than were boys in the lowest quartile of masculinity. Feminine girls were more likely, while masculine boys were less likely, to try to look like people in the media, compared, respectively, to least feminine girls and least masculine boys.

Table 1. Magazine reading and trying to look like men/women on TV by gender expression before age 11 years, Growing Up Today Study, 1996-1997 waves (N= 9,435).

| Type of magazine most often read | Try to look like men/women in the media | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Don't read magazines | Music, television, gossip | Sports | Teen, fashion | Health, fitness | Other | Never | A little | Sometimes | A lot | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| N | % | % | |||||||||

| Males | |||||||||||

| Gender expression | |||||||||||

| Least masculine | 416 | 20.0 | 7.5 | 16.8 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 54.1 | 66.4 | 24.6 | 3.9 | 5.1 |

| 2nd quartile | 1126 | 18.9 | 5.9 | 26.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 47.5 | 75.9 | 18.3 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| 3rd quartile | 720 | 18.8 | 4.7 | 30.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 45.3 | 69.2 | 24.0 | 3.6 | 3.2 |

| Most masculine | 1163 | 18.6 | 4.2 | 29.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 47.2 | 72.6 | 21.1 | 4.0 | 2.3 |

| Wald χ2 | P<0.001 | P<0.01 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Females | |||||||||||

| Gender expression | |||||||||||

| Least feminine | 1384 | 16.9 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 45.2 | 0.4 | 27.4 | 58.4 | 29.8 | 4.7 | 7.2 |

| 2nd quartile | 1058 | 16.5 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 52.1 | 0.5 | 23.8 | 59.8 | 30.1 | 3.9 | 6.2 |

| 3rd quartile | 1733 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 52.5 | 0.3 | 27.1 | 53.3 | 34.6 | 5.9 | 6.2 |

| Most feminine | 1835 | 16.0 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 54.1 | 0.3 | 25.5 | 55.6 | 30.6 | 6.6 | 7.2 |

| Wald χ2 | P<0.0001 | P<0.01 | |||||||||

In models examining repeated measures across adolescence and early adulthood, females in the highest quartile of femininity had higher risk of indoor tanning (pRR=1.32, 95% CI=1.23, 1.42) and physical inactivity (pRR=1.16, 95% CI=1.01, 1.34) compared with females in the lowest quartile of femininity (Table 2). Least-feminine females were more likely to follow a worse cigarette smoking trajectory (i.e., a trajectory associated with more health risks) or to smoke cigars compared with most-feminine females (Table 3). Males in the middle two quartiles of masculinity in childhood were less likely to tan indoors than the least masculine males (2nd quartile, pRR=0.68, 95% CI=0.54, 0.86; 3rd quartile, pRR=0.73, 95% CI=0.57, 0.95). Compared with least masculine males, males in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartile of masculinity (most masculine) were less likely to be physically inactive (pRR range, 0.54-0.74, Table 2). The most masculine males were more likely to chew tobacco (pRR=1.78, 95%CI=1.14, 2.79) and smoke cigars (pRR=1.55, 95% CI=1.17, 2.06) than the least masculine males (Table 3).

Table 2. Physical inactivity and indoor tanning by gender expression before age 11 years, Growing Up Today Study, 1996-2007 waves (N= 9,434)†.

| Physically inactive, past year | Indoor tanning, past year, any | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model 1a: Gender expression | Model 1b: Further adjusted for media engagement | Model 2a: Gender expression | Model 2b: Further adjusted for media engagement | |

| Prevalence risk ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|

| ||||

| MALES | ||||

| Gender expression | ||||

| Least masculine | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| 2nd quartile | 0.74 (0.59, 0.92)** | 0.77 (0.62, 0.96)* * | 0.68 (0.54, 0.86)** | 0.74 (0.59, 0.93)* |

| 3rd quartile | 0.55 (0.43, 0.72)*** | 0.60 (0.47, 0.77)** | 0.73 (0.57, 0.95)* | 0.78 (0.60, 1.00)* |

| Most masculine | 0.54 (0.43, 0.69)*** | 0.58 (0.46, 0.74)*** | 0.94 (0.75, 1.18) | 0.99 (0.80, 1.14) |

|

| ||||

| FEMALES | ||||

| Gender expression | ||||

| Least feminine | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| 2nd quartile | 1.01 (0.85, 1.19) | 1.01 (0.86, 1.20) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.15) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.13) |

| 3rd quartile | 1.10 (0.95, 1.27) | 1.11 (0.97, 1.28) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.23)** | 1.08 (1.00, 1.16)* |

| Most feminine | 1.16 (1.01, 1.34)* | 1.20 (1.04, 1.38)** | 1.32 (1.23, 1.42)*** | 1.21 (1.13, 1.30)*** |

Adjusted for age (continuous), race/ethnicity (white/nonwhite). Past-year physical inactivity measured in the 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2005 waves; past-year indoor tanning measured in the 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007 waves.

Wald χ2 P<0.05.

Wald χ2 P<0.01.

Wald χ2 P<0.001.

Table 3. Tobacco use by gender expression, Growing Up Today Study, 1996-2007 waves, (N= 9,434)†.

| Cigarette smoking, risk of worse trajectory across adolescence | Chewing tobacco use, past year, any | Cigar smoking, past year, any | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Model 1a: Gender expression | Model 1b: Further adjusted for media engagement | Model 2a: Gender expression | Model 2b: Further adjusted for media engagement | Model 3a: Gender expression | Model 3b: Further adjusted for media engagement | |

| Prevalence odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Prevalence risk ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| MALES | ||||||

| Gender expression | ||||||

| Least masculine | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| 2nd quartile | 0.67 (0.53, 0.85)*** | 0.77 (0.61, 0.98)* | 1.50 (0.95, 2.36) | 1.60 (1.00, 2.54)* | 1.18 (0.88, 1.58) | 1.20 (0.89, 1.60) |

| 3rd quartile | 0.64 (0.49, 0.83)*** | 0.71 (0.55, 0.93)** | 1.57 (0.96, 2.57) | 1.66 (1.01, 2.73)* | 1.31 (0.96, 1.78) | 1.33 (0.98, 1.80) |

| Most masculine | 0.69 (0.55, 0.87)** | 0.78 (0.62, 1.00)* | 1.78 (1.14, 2.79)* | 1.88 (1.19, 2.97)** | 1.55 (1.17, 2.06)** | 1.58 (1.19, 2.09)** |

| FEMALES | ||||||

| Gender expression | ||||||

| Least feminine | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] | 1.0 [reference] |

| 2nd quartile | 0.84 (0.71, 1.00)* | 0.84 (0.70, 1.00)* | 0.63 (0.36, 1.11) | 0.64 (0.36, 1.13) | 0.57 (0.42, 0.78)*** | 0.58 (0.43, 0.80)*** |

| 3rd quartile | 0.74 (0.63, 0.86)** | 0.70 (0.60, 0.82)*** | 0.92 (0.60, 1.43) | 0.88 (0. 57, 1.37) | 0.58 (0.45, 0.75)*** | 0.58 (0.45, 0.75)*** |

| Most feminine | 0.75 (0.65, 0.88)** | 0.70 (0.60, 0.82)*** | 0.68 (0.42, 1.08) | 0.60 (0.38, 0.94)* | 0.61 (0.47, 0.79)*** | 0.59 (0.46, 0.76)*** |

Adjusted for age and race/ethnicity (white/nonwhite). Past-year chewing tobacco use measured in the 1997, 1998, 1999, and 2001 waves. Past-year cigar smoking measured in the 2001 wave. Odds ratios of following a worse smoking trajectory were calculated with ordered logistic regression with a cumulative logit link and a multinomial distribution.

Wald χ2 P<0.05.

Wald χ2 P<0.01.

Wald χ2 P<0.001.

Media engagement accounted for approximately one-third to one-half of the higher risk of indoor tanning among females (2nd quartile, mediation=75.1%, p=0.08; 3rd quartile, mediation=56.2%, p<0.001; 4th quartile (most feminine), mediation=39.9%, p<0.001; Table 2, Models 2a, 2b). Media engagement accounted for a small portion of the lower risk of tanning among males in the 2nd quartile of masculinity (mediation=17.4%, p<0.05, Table 2, Models 2a, 2b), and lower risk of physical inactivity among masculine males (2nd quartile, mediation=20.3%, p<0.05; 3rd quartile, mediation=17.3%, p<0.001; 4th quartile (most masculine), mediation=14.4%, p<0.001; Table 2, Models 1a, 1b). Adding media engagement to models also attenuated gender-expression differences in odds of a worse smoking trajectory among males, although the odds remained statistically significantly lower for most-masculine males (from OR=0.69 to OR=0.78 for most masculine males, mediation=35.5%, p<0.01; 3rd quartile, mediation=26.7%, p<0.01; 2nd quartile, mediation=36.0, p<0.001, Table 3, Models 1a, 1b). Media engagement did not account for gender-expression differences in physical inactivity or cigarette smoking in females, or cigar smoking or chewing tobacco use in either sex.

Discussion

Our principal finding is that differences in adolescent and young adult cancer risk behaviors occurred by gender expression within the biological sexes as well as between the sexes. Most-feminine females were at higher risk of carcinogenic behaviors more prevalent among females, including tanning indoors and being physically inactive, and lower risk of behaviors more prevalent among males, including smoking cigars and following worse smoking trajectories, compared with females in the lowest quartile of femininity. Most-masculine males were at higher risk of smoking cigars and chewing tobacco, behaviors more prevalent among males, and lower risk of being physically inactive, a behavior more prevalent among females, compared with least-masculine males. Thus, our findings indicate that conforming to norms of masculinity and femininity in childhood may increase later risk of engaging in certain carcinogenic behaviors.

However, for some risk behaviors differences by gender expression occurred in unexpected ways: least-masculine males were more like to follow a worse smoking trajectory than were most-masculine males, and males in the middle two quartiles of masculinity were at lower risk of tanning indoors than least-masculine males. Least- versus most-masculine males may have been at elevated risk of cigarette smoking due to increased exposure to psychosocial stressors. Males who do not conform to gender norms in childhood are more likely to be bullied and experience childhood abuse compared to gender-conforming males[17, 25], and smoking is often adopted and maintained to facilitate social integration and to regulate negative affect[26-28]. As least-masculine boys are more likely to identify as gay or bisexual as adults[17], it may be that stressors related to sexual orientation increased risk of smoking in this group. It is possible that the association of tanning with body building[29] has made this behavior more appealing to boys and men seeking to appear masculine[30, 31]. Additionally, the most masculine boys and men may be more likely to be concerned with achieving the masculine ideal of the toned, muscular physique, and tanned skin can enhance the appearance of muscle definition, although neither of these factors could account for the higher prevalence of indoor tanning among men in the lowest quartile of masculinity.

Patterns of media engagement differed by gender expression. We found that these differences explained a sizeable part of gender-expression differences in indoor tanning among women, and some of the differences in indoor tanning among men. Media engagement accounted for a small part of gender-expression differences in physical inactivity and cigarette smoking and did not explain differences in cigar and chewing tobacco use. Our measures may not have adequately captured exposure to and internalization of ubiquitous media messages promoting certain cancer risk behaviors as masculine or feminine. Adolescents may receive messages about the meaning of these behaviors through other sources, including parents, peers, and other media not assessed in our measures.

Our study has several limitations. Our sample was comprised of children of nurses and was predominantly White (93%), thus findings may not apply to other racial/ethnic or socioeconomic groups. Enrollment into the cohort and dropout may have biased our results. Included participants had slightly lower prevalence of the highest-risk smoking trajectory and cigar smoking than excluded participants, although prevalences of physical inactivity and indoor tanning were similar. Gender expression was by self-report, however, a study comparing adulthood reporting of childhood gender expression with ratings based on childhood home video recordings found good concordance[32].

Qualitative studies of the characterization of risk behaviors as masculine or feminine have indicated that issues of “prettiness,” “competence,” “toughness,” “hardness” and “risk taking”[33] are related to adolescents' perceptions of the masculinity or femininity of risk behaviors. Media consumption patterns differ by gender beginning in early childhood[34-36]. Magazines frequently read by adolescents of both sexes present content focused on body image, appearance, and having a provocative, authority-challenging attitude[36], factors which may relate to tobacco use, exercise and tanning behavior[37-41]. As media engagement explained only a part of gender-expression differences in risk behavior, future research should explore other possible mechanisms, including socialization by parents[42] and peers[43, 44].

Our findings suggest that public health messages questioning the “masculinity” or “femininity” of cancer risk behaviors may be important to evaluate in prevention efforts: for example, that tanning makes one beautiful or that cigar and chewing tobacco use is rugged or manly. Given the long-term health consequences of engaging in cancer risk-behaviors in adolescence and early adulthood, prevention efforts challenging the perceived masculinity or femininity of risk behaviors to reduce their appeal to adolescents may have substantial benefits. Moreover, carcinogenic behaviors in middle and late adulthood may also be patterned by gender expression. Future research should investigate this possibility; such findings would have long-term implications for the role of gender expression in the development of cancer.

Implications and Contribution.

It is unknown whether cancer risk behaviors differ by gender expression within the sexes. This study found that masculine boys and feminine girls had substantially higher prevalence of some risk behaviors compared with gender-nonconforming adolescents. Prevention efforts challenging the “masculinity” and “femininity” of risk behaviors may reduce their appeal to adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants HD066963, HD057368. SB Austin is supported by Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, training grants MC00001 and Leadership Education in Adolescent Health Project 6T71-MC00009. The Nurses' Health Study II is funded in part by NIH CA50385. We acknowledge the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School for its management of The Nurses' Health Study II and the Growing Up Today Study. The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Every person who contributed significantly to the work is an author.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: The authors have no financial interests relevant to the work.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Andrea L. Roberts, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Margaret Rosario, Department of Psychology, City University of New York, The City College and Graduate Center, New York, NY.

Jerel P. Calzo, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, and the Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Heather L. Corliss, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, The Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Harvard Medical School.

Lindsay Frazier, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the Harvard Medical School, and the Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health.

S. Bryn Austin, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard School of Public Health, the Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA and the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Works cited

- 1.American Lung Association. Trends in Tobacco Use. American Lung Association; 2011. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everett SA, et al. Relationship Between Cigarette, Smokeless Tobacco, and Cigar Use, and Other Health Risk Behaviors Among U.S. High School Students. Journal of School Health. 2000;70(6):234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller AC, et al. Use of sunscreen, sunburning rates, and tanning bed use among more than 10 000 US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1009–1014. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sallis JF, et al. Ethnic, socioeconomic, and sex differences in physical activity among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nader PR, et al. Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity From Ages 9 to 15 Years. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(3):295–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2000;32(5):963–975. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer C, Blissett J, Oldfield C. Sexual orientation and eating psychopathology: the role of masculinity and femininity. The International journal of eating disorders. 2001;29(3):314–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RJ, Ricciardelli LA. Negative perceptions about self-control and identification with gender-role stereotypes related to binge eating, problem drinking, and to co-morbidity among adolescents. Journal of adolescent health. 2003;32(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCreary DR, Saucier DM, Courtenay WH. The Drive for Muscularity and Masculinity: Testing the Associations Among Gender-Role Traits, Behaviors, Attitudes, and Conflict. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6(2):83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dave DM, Saffer H. Demand for Smokeless Tobacco: Role of Magazine Advertising. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenman J, Jones DA. Comparison of advertising strategies between the indoor tanning and tobacco industries. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010;62(4):685.e1–685.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villani S. Impact of media on children and adolescents: a 10-year review of the research. Journal-American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):392–401. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the Movies Increases Adolescent Smoking: A Review. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1516–1528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakefield M, et al. Role of the media in influencing trajectories of youth smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:79–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho H, Choi J. Television, Gender Norms, and Tanning Attitudes and Intentions of Young Men and Women. Communication Studies. 2011;62(5):508–530. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker K, et al. The Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire: Psychometric properties. Sex Roles. 2006;54(7):469–483. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts AL, et al. Childhood gender nonconformity: A risk indicator for childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress in youth. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):410–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts AL, et al. Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(8):1587–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts AL, et al. Childhood Gender Nonconformity, Bullying Victimization, and Depressive Symptoms Across Adolescence and Early Adulthood: An 11-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corliss HL, et al. Role of depressive symptoms and self-esteem in explaining sexual-orientation disparities in trajectories of cigarette smoking during adolescence and emerging adulthood. preparation [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: a group-based method. Psychological methods. 2001;6(1):18–34. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertzmark E, et al. The SAS mediate macro. Brigham and Women's Hospital, Channing Laboratory; Boston: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin DY, Fleming TR, De Gruttola V. Estimating the proportion of treatment effect explained by a surrogate marker. Stat Med. 1997;16(13):1515–27. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970715)16:13<1515::aid-sim572>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts AL, et al. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: an 11-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(2):143–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Q, et al. Cognitive attributions for smoking among adolescents in China. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piko BF, Wills TA, Walker C. Motives for smoking and drinking: country and gender differences in samples of Hungarian and US high school students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(10):2087–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O. Cloninger's constructs related to substance use level and problems in late adolescence: a mediational model based on self-control and coping motives. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 1999;7(2):122. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan Ban. Iron Man Magazine. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cafri G, et al. An investigation of appearance motives for tanning: The development and evaluation of the Physical Appearance Reasons For Tanning Scale (PARTS) and its relation to sunbathing and indoor tanning intentions. Body Image. 2006;3(3):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blashill AJ, Traeger L. Indoor Tanning Use Among Adolescent Males: The Role of Perceived Weight and Bullying. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9491-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rieger G, et al. Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):46–58. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haines RJ, et al. “I couldn't say, I'm not a girl” – Adolescents talk about gender and marijuana use. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(11):2029–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valkenburg PM, Janssen SC. What do children value in entertainment programs? A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Communication. 1999;49(2):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knobloch S, et al. Children's sex-stereotyped self-socialization through selective exposure to entertainment: Cross-cultural experiments in Germany, China, and the United States. Journal of Communication. 2005;55(1):122–138. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosacki S, et al. Preadolescents' Self-concept and Popular Magazine Preferences. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 2009;23(3):340–350. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Austin SB, Gortmaker SL. Dieting and smoking initiation in early adolescent girls and boys: a prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(3):446. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.French SA, et al. Weight concerns, dieting behavior, and smoking initiation among adolescents: a prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(11):1818–1820. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazovich D, Forster J. Indoor tanning by adolescents: prevalence, practices and policies. European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders JM. Coming of Age: How Adolescent Boys Construct Masculinities via Substance Use, Juvenile Delinquency, and Recreation. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse. 2011;10(1):48–70. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2011.547798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loman DG. Promoting physical activity in teen girls: insight from focus groups. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2008;33(5):294. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000334896.91720.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenenbaum HR, Leaper C. Are parents' gender schemas related to their children's gender-related cognitions? A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(4):615. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu WM, Iwamoto DK. Conformity to masculine norms, Asian values, coping strategies, peer group influences and substance use among Asian American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2007;8(1):25. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ewing Lee EA, Troop-Gordon W. Peer socialization of masculinity and femininity: Differential effects of overt and relational forms of peer victimization. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2011;29(2):197–213. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2010.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]