Abstract

Background

Faecal occult blood tests are often the initial test in population-based screening. We aimed to: 1) compare the results of single sample faecal immunochemical tests (FITs) with colonoscopy, and 2) calculate the sensitivity for proximal vs. distal adenomatous polyps or cancer.

Methods

Individuals scheduled for a colonoscopy were invited to complete a FIT prior to their colonoscopy preparation. FIT results were classified as positive, negative, or invalid. Colonoscopy reports were reviewed and abstracted. Because of product issues, four different FIT manufacturers were used. The test characteristics for each FIT manufacturer were calculated for advanced adenomatous polyps or cancer according to broad reason for colonoscopy (screening or surveillance/diagnostic).

Results

Of those invited, 1,026 individuals (43.9%) completed their colonoscopy and had a valid FIT result. The overall sensitivity of the FITs (95% confidence intervals) was 0.18 (0.10 to 0.28) and specificity was 0.90 (0.87 to 0.91) for advanced adenomas or cancer. The sensitivity for distal lesions was 0.23 (0.11 to 0.38) and for proximal lesions was 0.09 (0.02 to 0.25). The odds ratio of an individual with a distal advanced adenoma or cancer testing positive was 2.68 (1.20 to 5.99). The two individuals with colorectal cancer tested negative, as did one individual with high-grade dysplasia.

Conclusions

The sensitivity of a single-sample FIT for advanced adenomas or cancer was low. Individuals with distal adenomas had a higher odds of testing positive than those with proximal lesions or no lesions.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, colorectal cancer screening, fecal immunochemical test, colonoscopy, sensitivity, specificity, test characteristics

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC), the second leading cause of cancer death1, is largely preventable, or very curable if detected early. However, approximately 60% of cases are diagnosed at a late stage when 5-year survival rates are very low.2

The United States national guidelines promote several tests for screening, including tests that detect occult blood and endoscopic tests that visualize the colon.3–5 Faecal occult blood tests (FOBTs) are recommended annually, while colonoscopy is recommended every 10 years, if no polyps are found. In the English population-based bowel screening programme, individuals aged 60 to 69 are mailed guaiac-based FOBTs every two years; this has recently been extended to age 74.6 The current European guidelines state that the guaiac FOBT interval should not exceed two years, and the faecal immunochemical test (FIT) interval should not exceed three years.7 These guidelines reported limited evidence for the efficacy of colonoscopy in reducing CRC incidence and mortality.7 The newer FITs generally have better sensitivity and slightly lower specificity for CRC and advanced polyps, compared with guaiac tests.8–10

FOBTs are much less expensive compared with colonoscopy, and are often preferred by patients.11,12 In many low income settings, FOBTs are the initial option for patient screening, due to the prohibitive cost and limited availability of colonoscopy.13,14

A decision analysis performed for the United States Preventive Services Task Force found no difference in life-years gained by CRC screening using colonoscopy every 10 years vs. annual testing with a sensitive FOBT or a FIT in individuals aged 50 to 75.15 Although studies using FIT followed by colonoscopy have been conducted in populations outside the United States16–20, we found none conducted in the United States directly comparing these methods. Quintero, et al compared over 50,000 individuals randomized to one-time FIT or colonoscopy in a Spanish population.21 CRC was found in 0.1% of both groups.

Some studies have reported that the sensitivity of FIT for distal adenomas is higher than for proximal adenomas.16,18,22,23

The purposes of this study were to: 1) compare the results of single sample FITs with colonoscopy, and 2) calculate the sensitivity for FIT for proximal vs. distal adenomatous polyps or cancer.

Methods

The study and methods were approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

Subject Recruitment

Individuals aged 40 to 75 who were scheduled for a screening, surveillance or diagnostic colonoscopy at University of Iowa Healthcare were mailed an invitation to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included: having familial polyposis syndromes, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease, or active rectal bleeding. Those with no symptoms were included in the screening group. Those with previous polyps or colorectal cancer were included in the surveillance group. Individuals with a change in bowel habits, anaemia, positive FOBT or FIT, or appetite change, or abdominal pain were included in the diagnostic group. We did not collect information on the recency of the previous colonoscopy for those in the surveillance group.

Together with the invitation letter, potential subjects were mailed an informed consent document, a FIT with directions, a form asking for the date the stool sample was obtained, and a postage-paid biohazard mailer for return of the signed informed consent and the FIT sample. A toll-free telephone number was provided to enable potential subjects to speak with a research team member. Within 7 to 10 days, non-responders were telephoned, up to three times, to confirm that the invitation had been received, encourage participation, and allow the potential subject to ask questions. If a month had passed and there was no response from a potential subject, a second mailing was sent if there was sufficient time for receipt of a stool sample prior to the scheduled colonoscopy. If the colonoscopy was rescheduled, up to another three telephone calls were made. If the subject returned either the FIT or the informed consent, we telephoned them to request the missing item, and a duplicate item was sent if needed.

Faecal Immunochemical Tests (FITs) Used in the Study

We used FITs rather than guaiac tests, because the FIT is highly specific for lower gastrointestinal bleeding, there are no medication or food restrictions, and patients prefer FIT to guaiac tests.8,24,25 We had used the Inverness Clearview ULTRA iFOB in our previous research, and this was the test initially chosen for this study.26,27 Our original intention was to use a single FIT manufacturer. However, due to issues with the FIT products (described in Table 1), four different FIT manufacturers were used sequentially. Each FIT result was matched with the corresponding colonoscopy result. In the United States, laboratory tests that are waived by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act (CLIA) can be completed in outpatient office settings. All of the FITs used in this study were CLIA-waived. All of the manufacturers claimed a lower limit of haemoglobin detection of 50 ng Hb/ml. The lower limit of haemoglobin detected by these FITs in micrograms per gram of stool is shown in Table 1. Fraser et al28 have recommended that all FITs list the lower limit of haemoglobin detected in micrograms per gram of stool.

Table 1.

Fecal immunochemical tests used in this study (n=1026)

| FIT Manufacturer |

Dates Used |

Test Device |

Sensitivity (ng haemoglobin/ ml and µg hemoglobin/g faeces) |

Number of in- study Subjects Tested (valid results only) |

Reason for FIT Switch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inverness Clearview ULTRA iFOB | January to February 2010 | Dipstick test strip | 50 ng/ml 50 µg/g faeces |

65 | Company changed product to cassette and changed their name |

| Alere Clearview iFOB Complete | March 2010 to March 2011 | Cassette | 50 ng/ml 6 µg/g faeces |

529 | Product recall; company did internal testing that indicated that the product did not test positive down to 50 ng hemoglobin/ml (due to high humidity in shipping containers shipped by sea from China) |

| Polymedco OC-Light iFOB | April 2011 to September 2011 | Dipstick test strip | 50 ng/ml 10 µg/g faeces |

346 | Positivity rate significantly lower than the first two FITs used; this product did not test positive at 50 ng hemoglobin/ml in our quality control testing. |

| Quidel QuickVue iFOB | October 2011 to January 2012 | Cassette | 50 ng/ml 50 µg/g faeces |

86 | Grant funding ended |

Collection of Stool Samples and Development of FITs

Subjects were instructed to collect their stool sample prior to the start of their colonoscopy preparation. The sample was mailed back in a supplied pre-paid postage mailer, and developed according to the manufacturer’s directions by two study team members, who witnessed and concurred on the final result. Samples were considered invalid if the liquid had escaped from the vial during transit or if the subject collected too much stool for the buffer to ascend the chromatography paper.

Medical Record Review Form

A detailed analysis of the colonoscopy report was conducted. Portions of a colonoscopy review form (available on request) created for previous CRC studies were used for this study.29–32 Every biopsy sample was classified by size, histology, and location in the colon using the World Health Organization classification system33, and those with any villous histology, serrated adenomas, high-grade dysplasia, or any adenomatous polyp 10 mm or greater in diameter were classified as advanced adenomatous polyps.4,34,35 Our size and histology classifications very closely reflect those used by Imperiale et al36 and Kim et al.37 Adenomas were classified as “proximal” if in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, or transverse colon; they were classified as “distal” if in the splenic flexure or below. There were two individuals with both a proximal and distal adenoma, and they were classified according to the location of the largest adenoma, which was distal in both cases.

Data Analysis

Data were stored in Microsoft Access and imported into SAS 9.2 for Windows (SAS 9.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) for analysis. The data were analyzed by manufacturer using three groups: screening, surveillance or diagnostic, and all combined. Diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopies were combined because these constitute a higher risk group. For each group, c contingency tables were constructed, and sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, likelihood ratio positive, and likelihood ratio negative were calculated for each of the four FIT manufacturers. Colonoscopy results were used as the gold standard and were considered positive if an adenocarcinoma or advanced adenoma was found. Invalid FIT results were excluded from these test characteristic calculations, so a FIT could only be positive or negative. To calculate confidence intervals (CIs) for the test characteristics that were proportions (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value), 95% exact binomial CIs were used. The 95% CIs for the diagnostic likelihood ratios were calculated using the method described by Simel et al.38 In the surveillance and diagnostic colonoscopy group, Polymedco OC-Light and Quidel QuickVue had 0.5 added to all of the cell counts of their contingency tables before calculation of test characteristics, as described by Altman et al.39 This was done as some cells had zero counts that prevented the calculation of finite likelihood ratio CIs.

A binary logistic regression model was constructed with FIT result (positive/negative) as the outcome and a predictor defining the location of advanced adenoma, while controlling for FIT manufacturer, age (continuous), and gender if necessary (adding to the model one at a time and determining if they altered the main effect of interest by at least 5%). For this analysis, subjects with both a proximal and distal adenoma were classified according to location of the largest polyp, because this would be the one likely to bleed (n=2 subjects).

A second binary logistic regression model assessed the relationship between most concerning polyp type (advanced adenoma or adenocarcinoma, other adenoma, or nothing concerning on biopsy/normal colonoscopy) and FIT results. This model was assessed for confounding with the same set of potential confounders and in the same manner as described above.

All models were assessed for multicollinearity, a sufficient number of events/non-events in the response, and the impact of influential observations (standardized Pearson residuals and DFBetas). Age, the only continuous potential confounder, was examined with polynomial terms to check for non-linear relationships with the log odds. Hypothesis testing was performed at a significance level of 0.05 and two-tailed.

Results

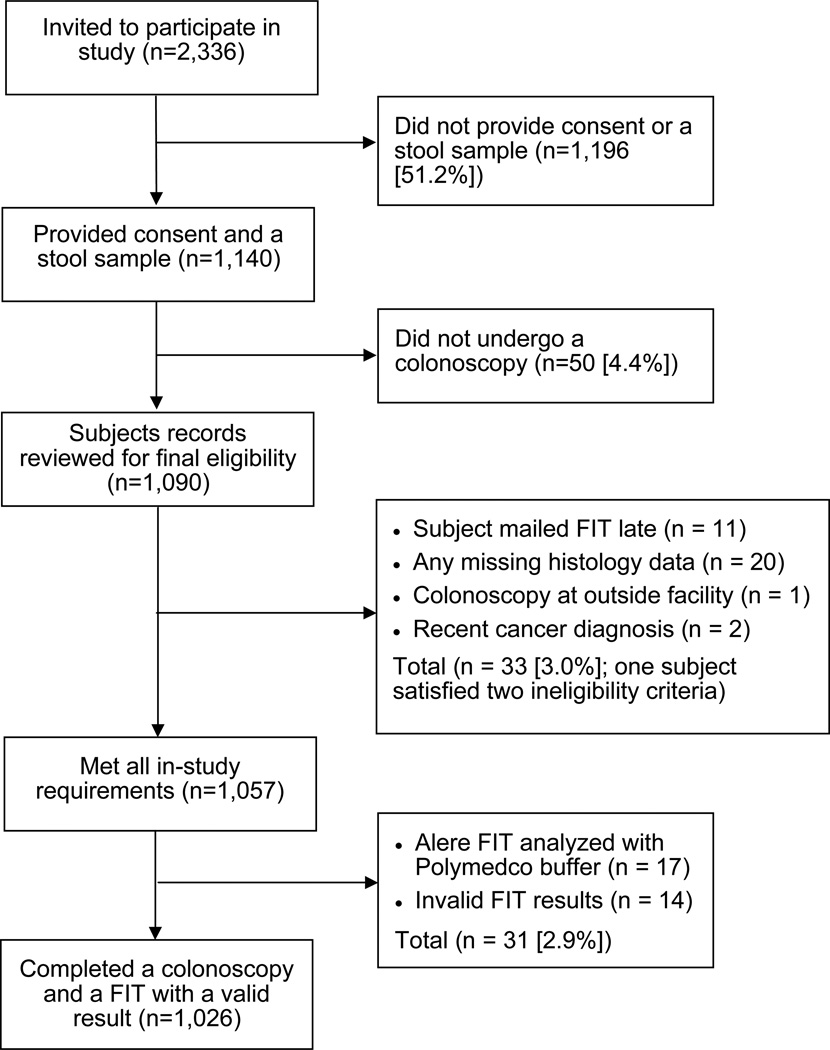

Between 22 January 2010 and 22 November 2011, invitations were mailed to 2,336 potential subjects, of whom 1,040 (44.5%) completed a FIT and a colonoscopy. Fourteen individuals had an invalid FIT result (1.4%), leaving 1,026 (43.9%) for analysis of test characteristics. A flow chart depicting how the final sample population was derived is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Study Subjects

The mean time from collection to testing of the FIT sample for the 606 subjects for whom data is available was 4.9 days (median 5.0 days; standard deviation 2.9 days) and right skewed with a range from 1 to 36 (90th percentile 8.0 days), suggesting that 90% of individuals returned their FIT within 8 days of sample collection.

Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2. The mean age was 57 years, 94% were white, and one-third had incomes below USD 40,000 per year.

Table 2.

Demographics (n=1040)*

| Mean age ± s.d. (years) | 56.9 ± 7.6 |

| Percentage female | 59.2% |

| Percentage married | 69.8% |

| Percentage white | 94.1% |

| Percentage African American | 2.3% |

| Percentage Latino | 1.3% |

| Percentage with income below USD 40,000 | 33.6%** |

| Percentage with high school education or less | 19.6% |

Includes those who enrolled who had invalid FIT results

63 missing responses; all other demographic variables listed above had less than 26 missing responses

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the adenomas and the advanced adenomas. Adenomas were found in one-third of the subjects (342/1040); of these, 22.5% had three or more and 20.5% had adenomas of 10 mm or greater. Of the total sample, 7% (73/1040) had advanced adenomas, and 52.1% of these had distal adenomas. Two or more advanced adenomas were found in 19.2% of the subjects with advanced adenomas. The size of the adenoma was not noted in three individuals with advanced adenomas (4.1% of those with advanced adenomas).

Table 3.

Adenoma Characteristics (n=1040 subjects)

| All adenomas (n = 342) |

Advanced adenomas only* (n = 73) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of adenomas by subject | ||||

| Only Proximal | 155 | (45.3%) | 31 | (42.5%) |

| Only Distal | 116 | (33.9%) | 38 | (52.1%) |

| Proximal and Distal | 69 | (20.2%) | 2 | (2.7%) |

| Location missing | 2 | (0.6%) | 2 | (2.7%) |

| Number of adenomas per subject | ||||

| One | 173 | (50.6%) | 59 | (80.8%) |

| Two | 92 | (26.9%) | 8 | (11.0%) |

| Three | 36 | (10.5%) | 2 | (2.7%) |

| Four or greater | 41 | (12.0%) | 4 | (5.5%) |

| Diameter of most concerning adenoma by subject** | ||||

| < 5 mm | 133 | (38.9%) | 1 | (1.4%) |

| ≤ 5 mm to < 10 mm | 136 | (39.8%) | 1 | (1.4%) |

| ≥ 10 mm | 70 | (20.5%) | 68 | (93.2%) |

| Size missing | 3 | (0.9%) | 3 | (4.1%) |

Advanced adenoma was defined as any tubulovillous, villous, serrated, or with high-grade dysplasia or a tubular polyp 10 mm or greater.

Most concerning is defined as the polyp with the most severe histology.

Table 4 shows the summary of histology results for patients, classified according to their most concerning result on colonoscopy, as well as the overall FIT results. Overall, we found two adenocarcinomas (0.2%) and one advanced adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, none of which tested positive on FIT. The overall FIT positivity rate was 10.8%.

Table 4.

Colonoscopy and FIT Results

| Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean (SD) |

Age | ||

| Men | 424 | (40.8) | 57.6 | (7.6) |

| Women | 616 | (59.2) | 56.3 | (7.6) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 | (0.2) | 49.5 | (7.8) |

| Advanced adenoma* and none of the above | 73 | (7.0) | 58.4 | (8.1) |

| Other adenoma (i.e., tubular and <10 mm), and none of the above | 267 | (25.7) | 58.2 | (8.0) |

| Hyperplastic polyp and none of the above | 200 | (19.2) | 56.4 | (7.0) |

| Other/No diagnostic abnormality/No histology performed/Lymphoid aggregate and none of the above | 498 | (47.9) | 56.1 | (7.5) |

| Positive FITs | 112 | (10.8) | 56.2 | (8.4) |

| Negative FITs | 914 | (87.9) | 56.9 | (7.5) |

| Invalid FITs | 14 | (1.4) | 55.9 | (7.3) |

| Total | 1040 | 56.9 | (7.6) | |

Advanced adenoma was defined as any tubulovillous, villous, serrated, or with high-grade dysplasia or a tubular polyp 10 mm or greater.

The test characteristics for each FIT manufacturer by group (screening, surveillance or diagnostic, and all combined) are shown in Table 5, along with CIs. When examining the screening group only, sensitivity was poor for all test manufacturers, but CIs were wide for some, limiting the usefulness of these estimates. Specificity was fairly high for each type of FIT, regardless of to which group the subject belonged. Similarly, the negative predictive value was high, indicating that if a person tested negative, they were not likely to have an advanced adenoma or carcinoma. The sensitivity was lowest for the Polymedco OC-Light. The overall sensitivity (95% CIs) was 0.18 (0.10 to 0.28) and specificity was 0.90 (0.87 to 0.91) for advanced adenomas or colorectal cancer. The sensitivity for distal advanced lesions was 0.23 (0.11 to 0.38) and for proximal advanced lesions was 0.09 (0.02 to 0.25).

Table 5.

Test Characteristics for Advanced Adenomas or Cancer for Four FIT Manufacturers*

| N | Company | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value |

Negative Predictive Value |

Likelihood Ratio Positive |

Likelihood Ratio Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Group | |||||||

| 44 | Inverness Clearview | 0.20 (0.01–0.72) | 0.92 (0.79–0.98) | 0.25 (0.01–0.81) | 0.90 (0.76–0.97) | 2.60 (0.33–20.46) | 0.87 (0.55–1.36) |

| 308 | Alere Clearview | 0.13 (0.02–0.41) | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | 0.05 (0.01–0.16) | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) | 0.98 (0.26–3.66) | 1.00 (0.82–1.23) |

| 217 | Polymedco OC-Light | 0.05 (0.00–0.26) | 0.99 (0.96–1.0) | 0.33 (0.01–0.91) | 0.92 (0.87–0.95) | 5.21 (0.50–54.85) | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) |

| 52 | Quidel QuickVue | 0.50 (0.01–0.99) | 0.88 (0.76–0.95) | 0.14 (0.0–0.58) | 0.98 (0.88–1.0) | 4.16 (0.86–20.15) | 0.57 (0.14–2.28) |

| Surveillance and Diagnostic Groups | |||||||

| 21 | Inverness Clearview | 0.67 (0.09–0.99) | 0.78 (0.52–0.94) | 0.33 (0.04–0.78) | 0.93 (0.68–1.0) | 3.0 (0.92–9.74) | 0.43 (0.08–2.16) |

| 221 | Alere Clearview | 0.33 (0.13–0.59) | 0.83 (0.77–0.88) | 0.15 (0.06–0.30) | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 1.99 (0.97–4.10) | 0.80 (0.57–1.12) |

| 129 | Polymedco OC-Light | 0.06 (0.00–0.41) | 0.94 (0.88–0.97) | 0.06 (0.00–0.45) | 0.93 (0.87–0.97) | 0.90 (0.06–14.59) | 1.0 (0.85–1.19) |

| 34 | Quidel QuickVue | 0.10 (0.00–0.63) | 0.89 (0.72–0.97) | 0.13 (0.00–0.72) | 0.86 (0.69–0.96) | 0.89 (0.05–14.69) | 1.01 (0.74–1.39) |

| All Groups | |||||||

| 65 | Inverness Clearview | 0.38 (0.09–0.76) | 0.88 (0.76–0.95) | 0.30 (0.07–0.65) | 0.91 (0.80 – 0.97) | 3.05 (0.98–9.47) | 0.71 (0.41–1.23) |

| 529 | Alere Clearview | 0.24 (0.11–0.42) | 0.85 (0.82–0.88) | 0.10 (0.04–0.18) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | 1.62 (0.86–3.08) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) |

| 346 | Polymedco OC-Light | 0.04 (0.00–0.19) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.10 (0.00–0.45) | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | 1.31 (0.17–9.98) | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) |

| 86 | Quidel QuickVue | 0.17 (0.00–0.64) | 0.89 (0.80–0.95) | 0.10 (0.00–0.45) | 0.93 (0.85–0.98) | 1.48 (0.22–9.83) | 0.94 (0.65–1.35) |

| 1026 | Overall | 0.18 (0.10–0.28) | 0.90 (0.87–0.91) | 0.12 (0.06–0.19) | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) | 1.69 (1.00–2.86) | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) |

Values in parentheses are the 95% confidence intervals

Table 6 shows a logistic regression model assessing variables which predicted positive FIT results. Model 1 shows that the presence of distal advanced adenomas or adenocarcinomas led to significantly greater odds (Odds Ratio [OR] = 2.68; 95% CI 1.20 to 5.99) for having a positive FIT result relative to no advanced adenoma or adenocarcinoma. Model 2 shows a nearly statistically significant result for individuals with advanced adenomas having increased odds of having a positive FIT relative to having no concerning polyps (OR = 1.96; 95% CI 1.00 to 3.84).

Table 6.

Predictors of Positive Fecal Immunochemical Test Results

| Model 1 (n=1024) |

Adenoma Location | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoma Location | Distal, advanced adenoma or adenocarcinoma | 2.68 | 1.20 to 5.99 | 0.02 |

| Proximal, advanced adenoma or adenocarcinoma | 0.96 | 0.28 to 3.28 | 0.94 | |

| No advanced adenoma or adenocarcinoma | 1.00 | - | - |

| Model 2 (n=1026) |

Most Concerning Polyp | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyp type | Advanced adenoma or adenocarcinoma | 1.96 | 1.00 to 3.84 | 0.05 |

| Other adenoma | 1.13 | 0.70 to 1.81 | 0.62 | |

| No concerning polyps | 1.00 | - | - |

All eligible subjects with valid FIT results included. Two subjects were removed for having missing biopsy location results that were required for analysis. Two subjects with both proximal and distal adenomas were classified according to the location of their most concerning lesion. Controlling for FIT manufacturer (Polymedco, Inverness, Alere, or Quidel).

All eligible subjects with a valid FIT result. Controlling for FIT manufacturer (Polymedco, Inverness, Alere, or Quidel) and gender.

The Polymedco product was not testing positively as often as the other FIT manufacturers, and we determined that it was not testing at the lower limit of sensitivity stated. We examined the relationship of Polymedco vs. all other FIT manufacturers pooled together for testing positive. Pooling was justified as the positivity rates for each of the other three FIT manufacturers were similar. This produced an OR of 5.93 (95% CI, 3.06 to 11.51) for Polymedco testing negative compared with the other manufacturers. Confounding was explored as an explanation of this relationship as with the previous models, but no evidence of this was found.

Discussion

This study assessed the test characteristics of a single-testing round of liquid-based FITs with optical colonoscopy as the gold standard. Several findings are notable: 1) the overall sensitivity of single-sample FITs for advanced adenomas and adenocarcinoma was low (18%), with a specificity of 90%, 2) Polymedco OC-Light had a statistically significantly lower test positivity rate than all of the other manufacturers, and 3) the sensitivity of the FIT for distal advanced lesions was higher than for proximal advanced lesions; those with advanced distal adenomas had higher odds of testing positive. It is likely that many primary care physicians are not aware of the limitations of FITs. We chose CLIA-waived FITs because many resource-poor settings are not able to provide universal access to colonoscopy, due to lack of colonoscopy providers, prohibitive costs, or both.14,40,41 The FIT is, therefore, potentially a very useful test for resourcepoor settings, and has also been recommended for other settings.40,42,43

During this two-year study, we had to use four different liquid-based FITs, when we originally intended to use a single manufacturer. One test was discontinued (Inverness Clearview ULTRA iFOB), one was withdrawn from the market (Alere Clearview ULTRA iFOB), but another with very low positivity compared with the other three manufacturers (Polymedco OC-Light) remains on the market. We discontinued use of Polymedco OC-Light, after we conducted more detailed quality control tests which indicated that it was not testing positive at the lower limit of haemoglobin concentration stated by the manufacturer.

When calculating test characteristics for specific groups and manufacturers, the subsets of data required were often small, resulting in limited precision, as seen through wide CIs. However, there is evidence that the specificity and negative predictive value were generally high across FIT products, and that the sensitivity and positive predictive value were generally low. It is important to note that this was only a single-sample testing round in a population that generally had access to CRC screening, and that when using FIT for screening, annual or biennial testing is recommended.4–7 The pooled estimates for FIT sensitivity for advanced adenomatous polyps or cancer was 0.18 (95% CI, 0.10 to 0.28) and specificity was 0.90 (0.87 to 0.91).

A Cochrane review has shown that FOBT, either annually or biennially, can reduce the risk of CRC mortality by about 15%.44 Among those attending at least one round, there was a 25% relative risk reduction, with no difference in all-cause mortality.44 The decision analysis by Zauber et al15 showed no difference in life-years gained when a strategy of annual FOBT was compared with a colonoscopy every 10 years. Zauber et al conducted sensitivity analyses assuming differing levels of adherence, and for a given level of adherence, the life-years gained were very similar between the two methods.15

Given the substantial numbers of false positive FITs that were not indicative of advanced adenomas, it would be useful to have a triage test for those with positive results. Despite research showing reasonable sensitivity and specificity for CT colonography in controlled settings37,45, CT colonography would probably not be a useful triage method in those with a positive FIT. Two studies have found relatively high rates of advanced adenoma or cancer (defined as a lesion 10 mm or greater in diameter or cancer) among those with a positive FIT.46,47 Regge et al reported a positive predictive value of 38.5% among FIT positive individuals and Liedenbaum reported a positive predictive value of 82% among those with positive FITs, using a definition of advanced lesion of adenomatous polyps 10 mm or larger or cancer.46,47 CT colonography therefore would not be a useful or cost-effective strategy, due to the fact that 40–80% of individuals undergoing CT colonography would need to go on to colonoscopy.

We found that the sensitivity of FIT for distal advanced lesions was higher than for proximal advanced lesions. This was confirmed by higher odds of patients with distal advanced adenomas testing positive in multivariable modelling. Others have also found higher sensitivity of the FIT for distal vs. proximal adenomas and adenomas greater than or equal to 10 mm in diameter, but did not report ORs for these.18,19,22

A good return rate of FITs was achieved for this study. Our original goal of obtaining 700 subjects was met. Numerous studies have shown that the FIT has higher sensitivity and is more acceptable to patients than the guaiac-based tests.10,48–50 Periodic FITs have been suggested as an alternative to the use of frequent surveillance colonoscopies.20

Studies outside the United States have investigated the use of automated FITs.8,9,22,25,51 Automated tests can be set to a lower limit of sensitivity depending on resources available for colonoscopy. In a study conducted in the early 1990s with 27,860 subjects, using the automated FIT, OC-Hemodia by Eiken, the manufacturer’s suggested cutoff of 50 ng/ml gave a sensitivity of 86.5% and specificity of 94.9% for CRC.52 In Taiwan, researchers used the same FIT and compared its findings with colonoscopic examination in 7,411 individuals.53 The FIT detected 48% of advanced neoplasms and 88% of cancers.53 Chiu et al22 reported on 18,296 individuals and found a sensitivity for advanced adenoma of 28.5% for the FIT and 78.6% for CRC.22 Our study results cannot be directly compared with these studies, because we used a non-automated CLIA-waived FIT. In addition, the populations tested in these studies were asymptomatic adults in an initial screening round, where it would be expected that higher sensitivities would result due to more individuals having a cancer or advanced lesion as yet undetected.54

Performance characteristics vary widely across FIT manufacturers when analyzing the same stool specimen.18,55 Our study differed from these in that we used a single FIT manufacturer in a given person, but it also provides evidence for variable performance characteristics across FIT manufacturers.

To assess the usefulness of FIT in comparison with colonoscopy, it must be used annually over a span of ten years. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to compare strategies of annual FIT vs. colonoscopy every ten years. Such studies have been conducted in Italy, where they have adopted a biennial programme with the use of an automated FIT. Crotta et al56 invited 2,959 individuals to participate and followed them for 8 years. They found that 60% of invited participants completed each round of FIT screening, but just under half (48%) attended all four rounds of screening. The rate of advanced adenoma detection was similar in each of the four rounds: 0.8 to 1.7%.56

Strengths of our study were that all the FITs were liquid-based and that we had a high return rate of FITs. Limitations include quality issues with the FITs, companies discontinued making their product (Inverness Clearview), removed their product from the market (Alere), and had very low sensitivity (Polymedco). These issues with the FITs were totally unexpected and could not have been anticipated at the start of the study. By the time we got to our fourth kit (Quidel), funding for the study ran out. Another limitation is that although the FITs were to be collected before patients started their colonoscopy preparation, we did not clearly specify how soon the samples were to be mailed after FIT collection. Other work has shown that delayed mailing and warmer weather leads to breakdown in haemoglobin (thus potentially more false negative samples).57 However, this was not a large factor in our study; the median time from collection to testing was 5.0 days and the 90th percentile was 8.0 days. Van Roon et al58 showed stability of FIT for up to 10 days before development, using an automated FIT, but as we used non-automated tests, which may have differing stabilities, this finding may not apply to our situation.

The accuracy for detecting advanced adenomas and CRC in this single round of testing was low, although the overall sensitivity for advanced adenomas or cancer (18%) was very close to the sensitivity of 22% estimated by Zauber et al15 for adenomas 10 mm or greater. FITs marketed in the United States are likely not to have undergone standard rigorous follow-up testing, because of the expense in having individuals undergo simultaneous testing with FIT and a colonoscopy, and in testing single samples across FIT brands. Although pathology laboratories participate in proficiency testing in order to remain accredited, they are probably not testing the FITs at the lower limit of positivity claimed in product inserts when using the manufacturer’s quality control solution. In addition, proficiency testing centres in the United States will not share how much haemoglobin is in their spiked samples.59 If the haemoglobin level in the spiked samples is considerably above the minimum threshold for a given test, then a specific manufacturer may look quite good on proficiency testing, when their product in reality does not test positive at the lower limit specified in the product insert.59 In addition, an individual hospital pathology laboratory might not realize that there is a trend in their positivity rate, unless they are diligently following trends over time.

Given our experience, it is clear that at least one FIT manufacturer does not test at the lower limit of sensitivity claimed. There are 8 FDA-approved and widely used FITs on the market.59,60 Manufacturers of CLIA-waived FITs have a responsibility to ensure that their products perform reliably at the level of sensitivity claimed. It is not reasonable to expect individual health centres to verify that these tests give positive results at the lower limit claimed. Ninety-three percent of samples tested by proficiency centres over a twoyear period were CLIA-waived tests, indicating that the overwhelming majority of testing in the United States is conducted with CLIA-waived FITs.59

Tests that produce false negative results may lull patients into a false sense of security, and many patients do not adhere to annual FOBTs, which would be necessary for adequate CRC screening.29 If FITs are to be used in resource-poor settings, for population-based screening, or as initial testing for individuals who prefer not to have a colonoscopy, then the manufacturer should ensure that the FIT is testing at the sensitivity specified in the product insert. Three of seven commonly used CLIA-waived FITs had low sensitivity and/or specificity on proficiency testing.59 In addition, once the FIT is found to test reliably at the lower limit of sensitivity stated, additional studies with larger sample sizes assessing test characteristics should be conducted, using colonoscopy as the gold standard. Many health centres simply do not have the funding to test their populations using non-CLIAwaived, automated tests, due to the large initial expense for equipment and the on-going need for trained laboratory technicians. For these populations, a valid, CLIA-waived FIT may be the only option for initial screening.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by NIH 1 RC1 CA144907-01 and the University of Iowa, Department of Family Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa.

The study sponsor, the National Cancer Institute, had no role in study design or in collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

Footnotes

Barcey T. Levy, PhD, MD, Study concept, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, wrote the initial and subsequent manuscript drafts and numerous revisions, obtained funding, study supervision

Camden Bay, MS, Analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision for intellectual content, statistical analysis

Yinghui Xu, MS, Acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data

Jeanette M. Daly, PhD, RN, Acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision for intellectual content, study supervision

George Bergus, MD, Study concept, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision for intellectual content

Jeffrey Dunkelberg, MD, Study concept, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision for intellectual content

Carol Moss, BS, Acquisition of data, critical revision for intellectual content, study supervision

All authors had full access to the data used. None of the authors has any disclosures.

References

- 1.What are the key statistics about colorectal cancer? [accessed 30 August 2013];2013 http://www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/detailedguide/colorectal-cancer-key-statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. [accessed 13 June 2014];Cancer Stat Fact Sheet Database-SEER 9 Regs Research Data. 2013 http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 3.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2009: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(1):27–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond JH, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodrow C, Watson E, Hewitson P, Austoker J Cancer Research UK Primary Care Education Research Group. The NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme Information for Primary Care. [accessed 14 March, 2014];2013 http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/bowel/bowel-ipc-booklet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, von Karsa L. International Agency for Research on Cancer. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition--Introduction. Endoscopy. 2012;44(Suppl 3):SE15–SE30. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1308898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park DI, Ryu S, Kim YH, Lee SH, Lee CK, Eun CS, et al. Comparison of guaiac-based and quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood testing in a population at average risk undergoing colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):2017–2025. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi Z, Birkenfeld S, Vilkin A, Bar-Chana M, Lifshitz I, Chared M, et al. A higher detection rate for colorectal cancer and advanced adenomatous polyp for screening with immunochemical fecal occult blood test than guaiac fecal occult blood test, despite lower compliance rate. A prospective, controlled, feasibility study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(10):2415–2424. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faivre J, Dancourt V, Denis B, Dorval E, Piette C, Perrin P, et al. Comparison between a guaiac and three immunochemical faecal occult blood tests in screening for colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(16):2969–2976. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segnan N, Senore C, Andreoni B, Azzoni A, Bisanti L, Cardelli A, et al. Comparing attendance and detection rate of colonoscopy with sigmoidoscopy and FIT for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2304–2312. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman RM, Steel SR, Yee EF, Massie L, Schrader RM, Moffett ML, et al. A system-based intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening uptake. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilschut JA, Habbema JD, van Leerdam ME, Hol L, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuipers EJ, et al. Fecal occult blood testing when colonoscopy capacity is limited. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(23):1741–1751. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winawer SJ, Krabshuis J, Lambert R, O'Brien M, Fried M World Gastroenterology Organization Guidelines Committee. Cascade colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a global conceptual model. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(4):297–300. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182098e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–669. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalid-de Bakker CA, Jonkers DM, Sanduleanu S, de Bruine AP, Meijer GA, Janssen JB, et al. Test performance of immunologic fecal occult blood testing and sigmoidoscopy compared with primary colonoscopy screening for colorectal advanced adenomas. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(10):1563–1571. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, Bossuyt PM, Meijer GA, van Ballegooijen M, van Roon AH, et al. Immunochemical fecal occult blood testing is equally sensitive for proximal and distal advanced neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(10):1570–1578. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hundt S, Haug U, Brenner H. Comparative evaluation of immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal adenoma detection. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):162–169. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morikawa T, Kato J, Yamaji Y, Wada R, Mitsushima T, Shiratori Y. A comparison of the immunochemical fecal occult blood test and total colonoscopy in the asymptomatic population. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terhaar sive Droste JS, van Turenhout ST, Oort FA, van der Hulst RW, Steeman VA, Coblijn U, et al. Faecal immunochemical test accuracy in patients referred for surveillance colonoscopy: a multi-centre cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, Cubiella J, Salas D, Lanas A, et al. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu HM, Lee YC, Tu CH, Chen CC, Tseng PH, Liang JT, et al. Association between early stage colon neoplasms and false-negative results from the fecal immunochemical test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(7):832–838. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalid-de Bakker C, Jonkers D, Smits K, Mesters I, Masclee A, Stockbrugger R. Participation in colorectal cancer screening trials after first-time invitation: a systematic review. Endoscopy. 2011;43(12):1059–1086. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman RM, Steel S, Yee EF, Massie L, Schrader RM, Murata GH. Colorectal cancer screening adherence is higher with fecal immunochemical tests than guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests: a randomized, controlled trial. Prev Med. 2010;50(5–6):297–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG, Fockens P, van Krieken HH, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jul;135(1):82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy BT, Daly JM, Luxon B, Merchant ML, Xu Y, Levitz C, et al. The "Iowa Get Screened" colon cancer screening program. J Prim Care Com Health. 2010;1(1):43–49. doi: 10.1177/2150131909352191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daly JM, Levy BT, Merchant ML, Wilbur J. Mailed fecal-immunochemical test for colon cancer screening. J Community Health. 2010;35(3):235–239. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser CG, Allison JE, Halloran SP, Young GP. Expert Working Group on Fecal Immunochemical Tests for Hemoglobin, Colorectal Cancer Screening Committee, World Endoscopy Organization. A proposal to standardize reporting units for fecal immunochemical tests for hemoglobin. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(11):810–814. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy BT, Dawson J, Hartz AJ, James PA. Colorectal cancer testing among patients cared for by Iowa family physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daly JM, Levy BT, Joshi M, Xu Y, Jogerst GJ. Patient clock drawing and accuracy of self-report compared with chart review for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(3):341–344. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy BT, Daly JM, Xu Y, Ely JW. Mailed fecal immunochemical tests plus education materials to improve colon cancer screening rates in Iowa Research Network (IRENE) practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(1):73–82. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy BT, Xu Y, Daly JM, Ely JW. A randomized controlled trial to improve colon cancer screening in rural family medicine: an Iowa Research Network (IRENE) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(5):486–497. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.05.130041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kudo S, Riboli E, Nakamura S, Hainaut P, et al. Tumours of the Colon and Rectum. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000. p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiraoka S, Kato J, Fujiki S, Kaji E, Morikawa T, Murakami T, et al. The presence of large serrated polyps increases risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1503–1510. 1510 e1–1510 e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Fletcher RH, Stillman JS, O’Brien MJ, Levin B, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(6):1872–1885. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Levin TR, Lavin P, Lidgard GP, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1287–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, Leung WK, Winter TC, Hinshaw JL, et al. CT colonography versus colonoscopy for the detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(14):1403–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ratios with confidence: sample size estimation for diagnostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(8):763–770. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90128-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ. Statistics with confidence: Confidence intervals and statistical guidelines. 2nd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allison JE. FIT: a valuable but underutilized screening test for colorectal cancer-it's time for a change. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):2026–2028. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daly JD, Levy BT, Moss CA, Bay CP. System strategies for colorectal cancer screening at federally qualified health centers. Am J Public Health. 2014 May 15; doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301790. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levin TR. Editorial: It's time to make organized colorectal cancer screening convenient and easy for patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(4):939–941. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flitcroft KL, Irwig LM, Carter SM, Salkeld GP, Gillespie JA. Colorectal cancer screening: why immunochemical fecal occult blood tests may be the best option. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:183. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1541–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, Butler JA, Puckett ML, Hildebrandt HA, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2191–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liedenbaum MH, van Rijn AF, de Vries AH, Dekker HM, Thomeer M, van Marrewijk CJ, et al. Using CT colonography as a triage technique after a positive faecal occult blood test in colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2009;58(9):1242–1249. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.176867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regge D, Laudi C, Galatola G, Della Monica P, Bonelli L, Angelelli G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomographic colonography for the detection of advanced neoplasia in individuals at increased risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(23):2453–2461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dancourt V, Lejeune C, Lepage C, Gailliard MC, Meny B, Faivre J. Immunochemical faecal occult blood tests are superior to guaiac-based tests for the detection of colorectal neoplasms. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(15):2254–2258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liles EG, Perrin N, Rosales AG, Feldstein AC, Smith DH, Mosen DM, et al. Change to FIT increased CRC screening rates: evaluation of a US screening outreach program. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(10):588–595. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rabeneck L, Rumble RB, Thompson F, Mills M, Oleschuk C, Whibley A, et al. Fecal immunochemical tests compared with guaiac fecal occult blood tests for population-based colorectal cancer screening. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(3):131–147. doi: 10.1155/2012/486328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levi Z, Rozen P, Hazazi R, Vilkin A, Waked A, Maoz E, et al. A quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test for colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(4):244–255. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Itoh M, Takahashi K, Nishida H, Sakagami K, Okubo T. Estimation of the optimal cut off point in a new immunological faecal occult blood test in a corporate colorectal cancer screening programme. J Med Screen. 1996;3(2):66–71. doi: 10.1177/096914139600300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng TI, Wong JM, Hong CF, Cheng SH, Cheng TJ, Shieh MJ, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in asymptomaic adults: comparison of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and fecal occult blood tests. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002;101(10):685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Boer R, Zauber A, Habbema JD. A novel hypothesis on the sensitivity of the fecal occult blood test: Results of a joint analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2410–2419. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tannous B, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Sharples C, Brugge W, Bigatello L, Thompson T, et al. Comparison of conventional guaiac to four immunochemical methods for fecal occult blood testing: implications for clinical practice in hospital and outpatient settings. Clin Chim Acta. 2009 Feb;400(1–2):120–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crotta S, Segnan N, Paganin S, Dagnes B, Rosset R, Senore C. High rate of advanced adenoma detection in 4 rounds of colorectal cancer screening with the fecal immunochemical test. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(6):633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, van Oijen MG, Fockens P, Laheij RJ, Verbeek AL, et al. False negative fecal occult blood tests due to delayed sample return in colorectal cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(4):746–750. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Roon AH, Hol L, van Vuuren AJ, Francke J, Ouwendijk M, Heijens A, et al. Are fecal immunochemical test characteristics influenced by sample return time? A population-based colorectal cancer screening trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(1):99–107. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daly JM, Bay CP, Levy BT. Evaluation of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(4):245–250. doi: 10.1177/2150131913487561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CLIA-Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. [accessed 12 September 2013];2013 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfClia/clia.cfm.