Abstract

The Kraepelinian distinction between schizophrenia (SZ) and bipolar disorder (BP) emphasizes affective and volitional impairment in the former, but data directly comparing the two disorders for hedonic experience are scarce. This study examined whether hedonic experience and behavioral activation may be useful phenotypes distinguishing SZ and BP. Participants were 39 SZ and 24 BP patients without current mood episode matched for demographics and negative affect, along with 36 healthy controls (HC). They completed the Chapman Physical and Social Anhedonia Scales, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS), and Behavioral Activation Scale (BAS). SZ and BP showed equally elevated levels of self-report negative affect and trait anhedonia compared to HC. However, SZ reported significantly lower pleasure experience (TEPS) and behavioral activation (BAS) than BP, who did not differ from HC. SZ and BP showed differential patterns of relationships between the hedonic experience and behavioral activation measures. Overall, the results suggest that reduced hedonic experience and behavioral activation may be effective phenotypes distinguishing SZ from BP even when affective symptoms are minimal. However, hedonic experience differences between SZ and BP are sensitive to measurement strategy, calling for further research on the nature of anhedonia and its relation to motivation in these disorders.

Keywords: psychosis, mania, emotional experience, anhedonia, motivation, reward processing

1. Introduction

Anhedonia – the diminished ability to experience pleasure – comprises one of the core negative symptoms of schizophrenia (SZ), closely related to amotivation and apathy, symptoms that severely interfere with daily functioning. Disturbances in hedonic experience are also observed in bipolar disorder (BP), evident by excessive pleasure-seeking during the manic state and reduced interest and pleasure during the depressive state. The Kraepelinian distinction between SZ and BP emphasizes affective and volitional impairment in the former (Kraepelin, 1921; Kendler, 1986), suggesting that emotional measures targeting hedonic experience, drive and motivation should differentiate the two diagnostic groups. However, emotional abnormalities, negative affect, and poor social adjustment characterize both SZ and BP (Blanchard et al., 1998; Elgie and Morselli, 2007; Gur et al., 2010; Rosa et al., 2010; Townsend and Altshuler, 2012; Kring and Elis, 2013; Michalak et al., 2013), which may reflect on assessments of hedonic capacity. This study sought to clarify whether hedonic experience and behavioral activation may be distinguishing phenotypes for SZ and BP.

Individuals with SZ have consistently shown elevated levels of anhedonia compared to healthy controls as assessed by interview-based (e.g., Sayers et al., 1996; Blanchard and Cohen, 2006) and self-report measures (Berenbaum and Fujita, 1994; Horan et al., 2008). However, experimental and experience-sampling studies have suggested the opposite, such that SZ participants often report equal levels of pleasant emotions in response to positive stimuli in the laboratory (Kring and Moran, 2008; Cohen and Minor, 2010) and similar intensity (though reduced frequency) of positive emotions in daily life as compared to healthy controls (Myin-Germeys et al., 2000; Myin-Germeys et al., 2001). A recent attempt to reconcile this “emotion paradox” in SZ distinguishes the ability to experience “in the moment” pleasure from the ability to anticipate pleasure. Using the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale, individuals with SZ were shown to have intact consummatory pleasure along with deficits in anticipatory pleasure in one study (Gard et al., 2007), although others have reported the opposite finding (Strauss et al., 2011). Recent neuroimaging data have shown abnormal reward learning and anticipation in SZ (see Ziauddeen and Murray, 2010 for review), as well as the failure to use prefrontal cortical mechanisms involved in reflecting upon emotional experience (Ursu et al., 2011). Gold and colleagues (Gold et al., 2008; Strauss and Gold, 2012; Strauss, 2013) asserted that rather than reflecting a reduced capacity to experience pleasure, anhedonia in SZ reflects impaired reward representation and low-pleasure beliefs in recalling and forecasting hedonic experience. This view provides a plausible explanation as to why individuals with SZ are able to experience inthe-moment pleasure yet show difficulty with representation and goal-related computations about potentially rewarding experiences. In addition, in contrast to findings of increased self-report anhedonia, the lack of overall difference in self-report behavioral activation between SZ and healthy controls (Barch et al., 2008; Scholten et al., 2006; Strauss et al., 2011) suggests that how questions are framed can influence the results and warrants further investigation.

Clinically, bipolar affective disorder (BP) is set apart from schizophrenia by the absence of significant negative symptoms, or at least those associated with the Kraepelinian ‘deficit’ syndrome (Carpenter et al., 1999a, 1999b). However, BP patients exhibit significant mood dysregulation, including depression with anhedonia, although few studies have examined the phenomenon of anhedonia in BP. These findings have been mixed, likely due to varied clinical states of the patients and also sampling and measurement factors. As would be expected, anhedonia is prevalent among BP patients in the depressed phase (52%; Mazza et al., 2009), and while the rate is much lower among euthymic patients (12% - 20.5%), it is still significantly higher than healthy controls (Etain et al., 2007; Di Nicola et al., 2013). In mood induction studies, BP patients have shown sustained elevations of positive emotions across positive, neutral, and negative contexts compared to controls (Farmer et al., 2006; Gruber et al., 2008, 2011a). They have also been shown to be less able to regulate positive emotions with cognitive restructuring techniques such as reappraisal compared with healthy individuals (Johnson et al., 2008; Gruber et al., 2009, 2011b). Together with self-report (Meyer et al., 2001; Hayden et al., 2008), behavioral (Hayden et al., 2008; Pizzagalli et al., 2008), electrophysiological (Hayden et al., 2008), and neuroimaging findings (Abler et al., 2008), there is ample evidence suggesting that abnormalities in hedonic experience in BP lie in a dysregulated reward-related behavioral activation system (BAS) that leads to abnormal goal pursuit.

Few studies have directly compared SZ and BP for hedonic experience. They have generally found that SZ has higher levels of anhedonia compared to BP. For example, Blanchard et al. (1994) found higher levels of physical and social anhedonia (as measured with the traditional Chapman scales) in SZ compared to a small sample of BP patients in manic or mixed state. Schürhoff et al. (2003) and Etain et al. (2007) also observed higher physical anhedonia in euthymic SZ compared to euthymic or recently manic BP. However, duration of illness and affective symptoms of the two clinical groups were often not well matched, calling for replications with samples better matched for these variables. Further, these studies assessed only trait anhedonia as measured with the Chapman scales; it remains unclear whether the two clinical groups also differ in other aspects of reward-related experience, such as consummatory vs. anticipatory pleasure and behavioral activation. Disorder-specific patterns of different aspects of reward-related experience would provide further understanding of the disease nature of SZ and BP.

In this study, we examined hedonic experience and behavioral activation in a sample of patients with stable SZ and BP matched for age, sex, parental education, illness duration, cognitive and social functioning, and negative affect symptoms. We compared the two clinical groups, with respect to a sample of healthy controls, using the Chapman Physical and Social Anhedonia Scales (Chapman et al., 1976; Eckblad et al., 1982), Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scales (TEPS; Gard et al., 2006), and the Behavioral Activation Scale (BAS; Carver and White, 1994). We hypothesized that SZ would report higher trait anhedonia as measured with the Chapman scales, equal consummatory pleasure but lower anticipatory pleasure on the TEPS, and lower behavioral activation as measured with the BAS when compared with BP and HC. We predicted that BP would report higher trait anhedonia (Chapman scales), but equal consummatory and anticipatory pleasure (TEPS) as well as behavioral activation (BAS) when compared with HC.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Forty-three patients with stable schizophrenia (n = 33) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 10) (SZ), 27 patients with bipolar disorder I (n = 24) or II (n = 3) (BP), and 36 healthy controls (HC) completed the study. Participant eligibility was determined using a screening checklist followed by the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID-I; First et al., 1995). Patients were recruited from local community mental health facilities and a university mental health clinic. Comorbid Axis I disorders were allowed, but those who were on a court-ordered treatment plan were excluded. Healthy controls were recruited via postings in the community and excluded if they had a history of mental, neurological, or serious physical illness that could affect brain functions, or a history of substance abuse/dependence in the past six months. All participants were between the ages of 18-70, and provided written informed consent after full explanation of the study was given. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and conducted in accordance with the sixth revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Thirty-seven of the SZ sample and 30 of the HC also completed a battery of self-report psychological measures that are outside the scope of this paper and reported elsewhere (Tso et al., 2012).

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1 Clinical Ratings

Clinical syndromes were further assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorham, 1962) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1983). The BPRS items of Hallucinatory Behavior, Unusual Thought Content, Suspiciousness, and Conceptual Disorganization were summed to form the positive symptoms subscore; Emotional Withdrawal, Motor Retardation, and Flat Affect were summed for the negative symptoms subscore. The total score of the SANS was obtained by summing the global scores on the Flat Affect, Alogia, Avolition, and Anhedonia subscales. Level of current depression was assessed using the Calgary Depression Scale (CDS; Addington et al., 1993). All of these were assessed by a trained Master's level clinical research associate prior to participants’ completion of the self-report measures described below.

2.2.2 Affective Symptoms

Participants completed self-report measures of negative affect: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996), the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al., 1970), and the Psychological Stress Index (PSI-18; Tso et al., 2012). These measures showed good internal consistency as indicated by Cronbach's alphas, ranged from .85 to .93 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of self-report measures of negative affect and hedonic experiences

| Variables | Number of items | SZ (n = 39) | BP (n = 24) | HC (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 21 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.88 |

| STAI | 20 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.90 |

| PSI | 18 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| Chapman Physical | 61 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.77 |

| Chapman Social | 40 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| TEPS Anticipatory | 10 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.39 |

| TEPS Consummatory | 8 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.66 |

| BAS Reward Responsiveness | 5 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.71 |

| BAS Drive | 4 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.89 |

| BAS Fun Seeking | 4 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.84 |

2.2.3 Self-report Hedonic Experience Measures

Self-report measures of hedonic experience included the Chapman Physical and Social Anhedonia Scales (Chapman and Chapman, 1976; Eckblad et al., 1982), Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS; Gard et al., 2006), and the Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System Scales (BIS/BAS; Carver and White, 1994). Because the subscales of the Chapman Anhedonia Scales, TEPS, and BAS contain different numbers of items, mean score (sum divided by the number of items) for each of the subscales was used in the analyses for easier comparisons. These measures showed satisfactory to good internal consistency (alphas ranged from 0.62 to 0.90), except for TEPS in HC (0.39) (see Table 2).

2.2.4 Functional Measures

The Reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT; Wilkinson, 1993) and the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS; Keefe et al., 2004) were used as estimates of verbal IQ and basic neurocognition, respectively. BACS composite scores were computed with reference to normal data of 83 healthy controls (30% female; age = 40.5 ± 11.7; parental education = 16.2 ± 2.6 years) from multiple studies by our research team. The Social Adjustment Scale—Self Report (SAS; Weissman and Multi-Health Systems, 1999) was used to assess social adjustment over the past 2 weeks, including six major areas: work, social and leisure activities, relationships with extended family, role as a marital partner, parental role, and role within the family unit. An overall adjustment score (possible range: 0 to 4) was calculated by reverse-coding the average score of items answered, with higher scores indicating better social adjustment.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The three diagnosis groups were compared for each of the demographics and negative affect using one-way ANOVA (or chi-square test for sex). For each of the self-report hedonic measures, the three groups were compared using mixed model ANOVA, with the subscales as within-subjects factor and diagnosis groups as between-subjects factor. Correlations between hedonic measures in SZ and BP were examined by Pearson's and Spearman correlations to investigate any differential relationships among these measures between the two clinical groups.

3. Results

SCID-derived diagnoses showed that 4 SZ and 2 BP participants were experiencing a current Major Depressive Episode, and 1 BP participant was experiencing a current Manic Episode. Given the concern of the influence of mood state on hedonic experience, these participants were excluded from the analyses. The final sample consisted of 39 SZ, 24 BP, and 36 HC, and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The three groups were well matched for age, sex, parental education, and family socioeconomic status. As expected, the two patient groups had fewer years of education, poorer neurocognition (BACS), and poorer social adjustment (SAS) than HC. SZ and BP showed very similar age of onset and duration of illness. As expected, SZ were higher on positive (BPRS positive) and negative symptoms (BPRS negative, SANS) than BP, while BP had higher clinical depressive symptoms (CDS) than SZ. Nevertheless, SZ and BP had same levels of self-report negative affect (BDI, STAI, and PSI-18).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variables | SZ (n = 39) | BP (n = 24) | HC (n = 36) | F / χ2 | Post-hoc group comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 41.5 ± 10.6 | 41.5 ± 11.4 | 40.4 ± 11.7 | 0.10 | -- |

| Sex (male/female) | 23 / 16 | 13 / 11 | 23 / 13 | 0.58 | -- |

| Education (years) | 13.8 ± 2.6 | 14.3 ± 2.4 | 15.9 ± 2.3 | 6.94** | SZ = BP < HC |

| Parental education | 15.5 ± 3.6 | 14.7 ± 3.4 | 14.8 ± 2.8 | 0.57 | -- |

| Family socioeconomic status | 2.72 ± 0.86 | 2.58 ± 0.72 | 2.61 ± 0.69 | 0.29 | -- |

| Illness onset age | 19.6 ± 6.7 | 17.3 ± 8.1 | -- | 1.52 | -- |

| Duration of illness | 21.9 ± 11.2 | 24.2 ± 13.0 | -- | 0.56 | -- |

| Medications | |||||

| Antipsychotics | 37 (95%) | 16 (67%) | -- | 8.85**a | SZ > BP |

| Conventional | 9 (23%) | 2 (8%) | -- | 0.95b | -- |

| Atypical | 31 (80%) | 15 (63%) | -- | 0.97a | -- |

| Chlorpromazine equivalents (mg daily) | 532 ± 541b | 376 ± 288 | -- | 1.17 | -- |

| Antidepressants | 10 (26%) | 12 (50%) | -- | 3.88 | -- |

| Anxiolytics | 5 (13%) | 7 (29%) | -- | 2.58 | -- |

| Mood stabilizers | 9 (23%) | 11 (46%) | -- | 3.55 | -- |

| Clinical symptoms | |||||

| BPRS positive | 10.7 ± 3.5 | 5.9 ± 2.5 | -- | 34.40*** | SZ > BP |

| BPRS negative | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | -- | 22.60*** | SZ > BP |

| BPRS total | 37.7 ± 6.9 | 30.1 ± 7.6 | -- | 16.74*** | SZ > BP |

| SANS Avolition | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | -- | 5.93* | SZ > BP |

| SANS Anhedonia | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | -- | 5.57* | SZ > BP |

| SANS total | 8.9 ± 3.3 | 5.3 ± 3.2 | -- | 18.34*** | SZ > BP |

| CDS | 1.3 ± 1.9 | 3.0 ± 2.9 | -- | 7.17** | SZ < BP |

| Functional measures | |||||

| WRAT | 48.2 ± 7.3 | 49.8 ± 4.5 | 51.0 ± 3.9 | 2.41 | -- |

| BACS | −1.89 ± 1.24 | −1.45 ± 1.12 | −0.07 ± 1.05 | 24.89*** | SZ = BP < HC |

| SAS | 2.84 ± 0.60 | 2.73 ± 0.63 | 3.46 ± 0.25 | 19.57*** | SZ = BP < HC |

| Negative affect | |||||

| STAI | 43.1 ± 10.8 | 41.5 ± 12.5 | 27.6 ± 7.2 | 25.07*** | SZ = BP > HC |

| BDI | 11.4 ± 8.4 | 13.2 ± 11.0 | 2.7 ± 4.5 | 16.01*** | SZ = BP > HC |

| PSI-18 | 2.06 ± 0.55 | 2.06 ± 0.60 | 1.14 ± 0.53 | 31.83*** | SZ = BP > HC |

Fisher's Exact Test.

n = 35.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

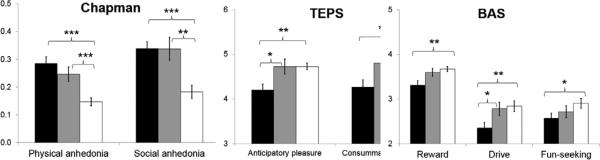

Results of hedonic and behavioral activation measures are presented in Figure 1. On the Chapman scales, both SZ and BP reported higher anhedonia than HC [F(2, 96) = 13.75, p < 0.001]. Participants generally reported higher social than physical anhedonia [F(1, 96) = 19.46, p < 0.001], with no differential patterns between the groups [F(2, 96) = 1.28, p = 0.28]. However, on the TEPS, SZ reported significantly lower pleasure experience than BP, who did not differ from HC [F(2, 96) = 6.09, p = 0.003]. Participants generally reported equal anticipatory and consummatory pleasure [F(1, 96) = 1.05, p = 0.31], and the effect of pleasure type was same across groups [F(2, 96) = 0.01, p = 0.99]. Results of the BAS showed decreased overall behavioral activation in SZ relative to BP and HC [F(2, 96) = 6.84, p = 0.002], with no significant difference between BP and HC. While participants generally scored higher on the Reward Responsiveness subscale than the Drive subscale on the BAS [F(2, 192) = 78.20, p < 0.001], this difference did not differ across groups [F(4, 192) = 0.57, p = 0.68].

Figure 1.

Hedonic experience and behavioral activation measures in SZ, BP, and HC. *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001

Inter-correlations between the hedonic measures are displayed in Table 3. Parametric (Pearson's r) and non-parametric (Spearman's ρ) results were very similar. Among the SZ participants, TEPS was moderately or strongly correlated with the Chapman scales (r ranged from -0.42 to -0.66; ρ ranged from 0.32 to 0.58) and BAS (r ranged from 0.36 to 0.56; ρ ranged from 0.30 to 0.51). Among the BP participants, the correlations between TEPS and BAS were largely non-significant (except for the correlation between TEPS Consumatory Pleasure and BAS Drive), but strong correlations were observed between TEPS and the Chapman scales (r ranged from -0.43 to -0.69; ρ ranged from 0.34 to 0.66).

Table 3.

Correlations between hedonic measures in 39 SZ and 24 BP

| Variables | 1a. | 1b. | 2a. | 2b. | 3a. | 3b. | 4a. | 4b. | 4c. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a. SANS Avolition | r | -- | (0.27) | (0.23) | (0.16) | (0.07) | (−0.04) | (0.23) | (0.26) | (0.12) |

| ρ | -- | (0.25) | (0.32) | (0.21) | (0.03) | (−0.09) | (0.19) | (0.25) | (0.15) | |

| 1b. SANS Anhedonia | r | 0.46** | -- | (0.16) | (0.43*) | (−0.15) | (−0.05) | (0.10) | (0.19) | (0.33) |

| ρ | 0.45** | -- | (0.19) | (0.45*) | (−0.07) | (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.24) | (0.38) | |

| 2a. Physical Anhedonia | r | 0.08 | 0.20 | -- | (0.56**) | (−0.43*) | (−0.69***) | (−0.18) | (−0.13) | (−0.20) |

| ρ | 0.03 | 0.13 | -- | (0.57**) | (−0.34) | (−0.66***) | (−0.11) | (−0.17) | (−0.09) | |

| 2b. Social Anhedonia | r | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.65*** | -- | (−0.65***) | (−0.65***) | (0.07) | (−0.05) | (0.07) |

| ρ | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.43** | -- | (−0.57**) | (−0.55**) | (0.13) | (−0.04) | (0.23) | |

| 3a. TEPS Anticipatory | r | −0.04 | −0.35* | −0.46*** | −0.42** | -- | (0.73***) | (0.32) | (0.50*) | (0.17) |

| ρ | 0.05 | −0.20 | −0.35* | −0.32* | -- | (0.53**) | (0.20) | (0.51*) | (0.08) | |

| 3b. TEPS Consummatory | r | −0.00 | −0.15 | −0.66*** | −0.50** | 0.60*** | -- | (0.21) | (0.27) | (0.25) |

| ρ | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.58*** | −0.36* | 0.53*** | -- | (0.00) | (0.20) | (0.25) | |

| 4a. BAS Reward Responsiveness | r | −0.28 | −0.34* | −0.28 | −0.49** | 0.49** | 0.37* | -- | (0.37) | (0.25) |

| ρ | −0.29 | −0.29 | −0.20 | −0.42** | 0.48** | 0.30 | -- | (0.39) | (0.36) | |

| 4b. BAS Drive | r | 0.03 | −0.38* | −0.18 | −0.18 | 0.43** | 0.36* | 0.37* | -- | (0.34) |

| ρ | −0.06 | −0.41* | −0.23 | −0.18 | 0.42** | 0.35* | 0.34* | -- | (0.36) | |

| 4c. BAS Fun Seeking | r | −0.10 | −0.23 | −0.32* | −0.12 | 0.56*** | 0.37* | 0.31 | 0.20 | -- |

| ρ | −0.16 | −0.22 | −0.44** | −0.14 | 0.51*** | 0.35* | 0.43** | 0.20 | -- |

Note. Correlations for SZ are displayed below the diagonal, and those for BP are displayed above the diagonal in parentheses.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01

P < 0.001 (not corrected for multiple comparisons)

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether self-report hedonic experience and behavioral activation may serve as phenotypes to distinguish SZ from BP. As hypothesized, we found that even when well matched for functional levels and negative affect, euthymic individuals with SZ and BP differed in hedonic experience and behavioral activation in general. Compared to BP participants, SZ participants showed elevated anhedonia and avolition as measured with the SANS, lower anticipatory and consummatory pleasure as measured with the TEPS, and decreased reward responsiveness as measured with the BAS. In addition, BP participants’ scores on the TEPS and BAS were statistically indistinguishable from HC, suggesting preserved hedonic experience and behavioral activation during the euthymic state of bipolar disorder. This result provides support for the use of hedonic and behavioral activation measures as distinguishing phenotypes for SZ and BP.

However, the difference in hedonic experience between SZ and BP appeared to vary with measurement strategy. Although the two clinical groups showed differential hedonic experience on most of the measures used in this study, they exhibited equally elevated levels of physical and social anhedonia on the Chapman scales compared to HC. This may be due to differences in the content and item construction between the Chapman scales and the TEPS and BAS. In terms of content, the Chapman scales include many items that are about experiences less likely to be accessible to individuals with mental disorder— who often have reduced economic and social resources (De Silva et al., 2005; Dohrenwend, 1990) (e.g., walking on the beach, singing with others). Thus, a “false” response to these statements might reflect an absence (or low frequency) of these experiences rather than a reduced hedonic ability or anticipation. Whereas for TEPS and BAS, the items concern more general experiences that individuals with SZ or BP may be more readily to relate to (e.g., eating a cookie, the night before a holiday, trying something new). Further, the TEPS does not include items related to social pleasure, so the Chapman scales and the TEPS scales possibly measure separate constructs of anhedonia. In terms of item construction, many items in the Chapman scales are framed in the past or present prefect tense (e.g., “I have often enjoyed...” “...food has always been...”), essentially asking about the respondent's past experience or their recall of these experiences. In contrast, items on the TEPS and BAS are often hypothetical or in the present or future tense, thus assessing the respondent's projection of their enjoyment in those situations. Taken together, our result of elevated Chapman anhedonia scores in both SZ and BP, but similar TEPS and BAS scores in BP and HC (but lower in SZ), suggests that the difference in hedonic experience between BP and SZ may lie in BP's preserved expectation of pleasure and reward despite reduced pleasurable events in life. This is consistent with previous laboratory data suggesting a heightened sensitivity to reward in euthymic BP (Pizzagalli et al., 2008), which may be a vulnerability to intensification of manic symptoms over time (Meyer et al., 2001).

Indeed, another finding in this study supported that SZ and BP have differential relationships between hedonic experience and behavioral activation. BP showed lower correlations between the BAS subscales and other hedonic measures than did SZ. This is unlikely due to the smaller sample size of the BP group and lower power to detect correlations, because we noted robust correlations between TEPS and the Chapman scales in the BP sample, similar to the magnitudes seen in the SZ sample. There is evidence that goal-attainment or goal-striving events, rather than positive events, predict prospective manic symptoms in BP (Johnson et al., 2000; Nusslock et al., 2007). Our finding of the dissociation between behavioral activation and hedonic experience in BP is therefore consistent with the view that the malfunction of the behavioral active system in BP lies in disproportionally high output of approach behavior in response to incentive-related events (Meyer et al., 2001). These findings have potential treatment implication for SZ and BP: while treatment focus for SZ should focus on increasing pleasurable activities and reappraisal of reward so to foster normative beliefs of pleasure and reward (Strauss and Gold, 2012) and improve motivation (Grant et al., 2012), treatment for BP may emphasize accurate differentiation of rewarding vs. non-rewarding stimuli and strengthening of response inhibition.

Our finding of equally elevated anhedonia on the Chapman scales in SZ and BP contradicts previous reports of higher anhedonia in SZ than euthymic (Schürhoff et al., 2003) or recently manic BP patients (Blanchard et al., 1994). This discrepancy may be due to the varied participant characteristics across studies, including male-female proportion, affective states, medication status, and illness chronicity. In particular, previous data suggest that anhedonia is a relatively stable trait in schizophrenia (Blanchard et al., 2001; Loas et al., 2009) but a state-dependent feature in affective disorders (Blanchard et al., 2001), including bipolar disorder (Katsanis et al., 1992). This highlights the importance of matching the affective symptoms between the two groups in future studies. This also suggests that the time course of self-report anhedonia may be a phenotype that may provide further insight into the differential disease processes in these two disorders.

Contrary to our prediction that SZ participants would show deficits in anticipatory but not consummatory pleasure on the TEPS, SZ participants reported lower pleasure in both dimensions relative to BP and HC. This result lies intermediate between those reported by Gard et al. (2007) (that SZ showed deficits in anticipatory but not consummatory pleasure) and Strauss et al. (2011) (that SZ showed reduced consummatory but not anticipatory pleasure). Further, we found that both TEPS anticipatory and consummatory pleasure—not only anticipatory pleasure as reported in Gard et al. (2007)—were correlated with BAS (especially the Reward Responsiveness subscale). These correlations were not observed among BP. As discussed above, since the TEPS consummatory pleasure subscale requires projection of affective state in hypothetical situations, it remains unclear how this score corresponds to one's true ability to experience in-the-moment pleasure. We are not aware of any published laboratory and experience-sampling studies directly comparing in-the-moment hedonic experience in SZ and BP. Such studies would help clarify the true magnitude of differences in consummatory pleasure between SZ and BP.

It is noteworthy that in the SZ group, SANS Avoliton appeared to be quite unrelated to the self-report anhedonia/hedonic experience measures. This contradicts the traditional assumption that reduced goal-directed behavior is related to reduced hedonic experience and also factor analysis results showing that anhedonia and avolition items on the SANS load on the same latent factor (Mueser et al., 1994; Sayers et al., 1996). However, the relationship between anhedonia and amotivation has been recently challenged. Horan et al. (2006) argued that decreased interest and engagement in goal-directed activities may be the result of a number of psychosocial and cognitive factors, in addition to anhedonia. Similarly, Strauss et al. (in press) proposed that the motivational problem in SZ is due to a failure to translate the hedonic experience into goal-directed behavior rather than an impaired hedonic capacity. They recommended several promising psychological and neural mechanisms of motivational impairment in SZ—including reinforcement learning, value representation, uncertainty-driven exploration, and effort-cost computation—to be further examined in future research.

It was noted that the internal consistency of the TEPS anticipatory subscale for HC was remarkably lower than for the patient groups. This was unlikely due to random responses to the items, as the HC group showed consistently good internal consistency for other scales used. The low internal consistency may be due to the generally narrower response range in HC than the patient groups, thus limiting the reliability of the correlation estimates used in the computation of Cronbach's alpha. An examination of the items also revealed that two items were particularly problematic: Item 11 (“When I'm on my way to an amusement park, I can hardly wait to ride the roller coasters”) and Item 13 (“I don't look forward to things like eating out at restaurants”—reversed coded). Deletion of Item 11 and Item 13 would increase Cronbach's alpha from .39 to .51 and .48, respectively. Removal of both items would increase alpha to .62. For Item 11, our speculation is that the nature of “pleasure” described in Item 11 is debatable, depending on other factors such as the person's excitement-seeking tendency. For Item 13, it may be a cognitively challenging item to respond to because of the negation, though it is unclear why it was not a particular problem in the patient groups.

This study is limited by its cross-sectional nature and use of chronic and medicated patients. Longitudinal studies including at-risk and first-episode samples may provide further insight into differential hedonic experience and behavioral activation between SZ and BP as a function of illness stage and affective states. Given some evidence that conventional antipsychotics produce more deficits in reward anticipation compared to their atypical counterparts (Juckel et al., 2006), the role of medication in the differential hedonic experience and behavioral activation between SZ and BP needs to be further explored. Use of larger samples in future studies would also allow more sophisticated statistical tests to examine the dynamic relationships between different aspects of reward processing and behavior.

To conclude, individuals with SZ showed reduced hedonic experience and behavioral activation relative to those with BP, providing evidence that these may be effective phenotypes distinguishing the two disorders even when affective symptoms are stable and minimal. However, differences in hedonic experience between SZ and BP are sensitive to measurement strategy, calling for further research on the nature of anhedonia and its relation to motivation in these disorders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abler B, Greenhouse I, Ongur D, Walter H, Heckers S. Abnormal reward system activation in mania. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2217–2227. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the Calgary Depression Scale (CDS). The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;22(Suppl.):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) University of Iowa; Iowa City, IA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Yodkovik N, Sypher-Locke H, Hanewinkel M. Intrinsic motivation in schizophrenia: relationships to cognitive function, depression, anxiety, and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:776–787. doi: 10.1037/a0013944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Fujita F. Schizophrenia and personality: exploring the boundaries and connections between vulnerability and outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:148–158. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS, Mueser KT. Affective and social-behavioral correlates of physical and social anhedonia in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:719–728. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Mueser KT, Bellack AS. Anhedonia, positive, and negative affect, and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24(3):413–424. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Horan WP, Brown SA. Diagnostic differences in social anhedonia: a longitudinal study of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:363–371. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(2):238–245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, Arango C, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B. Deficit psychopathology and a paradigm shift in schizophrenia research. Biological Psychiatry. 1999a;46(3):352–360. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW. Schizophrenia: syndromes and diseases. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1999b;33(6):473–475. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(99)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(2):319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(1):143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:374–382. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva MJ, McKenzie K, Harpham T, Huttly SR. Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59:619–627. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicola M, De Risio L, Battaglia C, Camardese G, Tedeschi D, Mazza M, Martinotti G, Pozzi G, Niolu C, Di Giannantonio M, Siracusano A, Janiri L. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147(1-3):446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Socioeconomic status (SES) and psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1990;25:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00789069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad ML, Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Mishlove M. Revised Social Anhedonia Scale. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1982;94:384–396. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.3.384. Unpublished scale reported in Mishlove, M., Chapman, L.J., 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgie R, Morselli PL. Social functioning in bipolar patients: the perception and perspective of patients, relatives, and advocacy organizations - a review. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9(1-2):144–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etain B, Roy I, Henry C, Rousseva A, Schürhoff F, Leboyer M, Bellivier F. No evidence for physical anhedonia as a candidate symptom or an endophenotype in bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9(7):706–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A, Lam D, Sahakian B, Roiser J, Burke A, O'Neill N, Keating S, Smith GP, McGuffin P. A pilot study of positive mood induction in euthymic bipolar subjects compared with healthy controls. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1213–1218. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Version 2.0. Biometrics Research; New York: 1995. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Gard MG, Kring AM, John OP. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: a scale development study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:1086–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, Horan WP, Green MF. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;93(1-3):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Waltz JA, Prentice KJ, Morris SE, Heerey EA. Reward processing in schizophrenia: a deficit in the representation of value. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:835–847. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PM, Huh GA, Perivoliotis D, Stolar NM, Beck AT. Randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of cognitive therapy for low-functioning patients with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):121–127. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Johnson SL, Oveis C, Keltner D. Risk for mania and positive emotional responding: too much of a good thing? Emotion. 2008;8:23–33. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Harvey AG, Johnson SL. Reflective and ruminative processing of positive emotional memories in bipolar disorder and healthy controls. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 2009;47:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Harvey AG, Purcell AL. What goes up can come down? A preliminary investigation of emotion reactivity and emotion recovery in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011a;133:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Eidelman P, Johnson SL, Smith B, Harvey AG. Hooked on a feeling: rumination about positive and negative emotion in inter-episode bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011b;120:956–961. doi: 10.1037/a0023667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Keutmann MK, Gur RE. Understanding emotion processing in schizophrenia. Die Psychiatrie: Grundlagen und Perspektiven [The Psychiatry: Principles and Perspectives. 2010;7(4):217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Sigelman J. State anger and prefrontal brain activity: evidence that insult related left prefrontal activity is associated with experienced anger and aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:797–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Bodkins M, Brenner C, Shekhar A, Nurnberger JI, Jr., O'Donnell BF, Hetrick WP. A multimethod investigation of the behavioral activation system in bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):164–170. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Blanchard JJ, Clark LA, Green MF. Affective traits in schizophrenia and schizotypy. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(5):856–874. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:259–273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Sandrow D, Meyer B, Winters R, Miller I, Solomon D, Keitner G. Increases in manic symptoms after life events involving goal attainment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:721–727. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, McKenzie G, McMurrich S. Ruminative responses to negative and positive affect among students diagnosed with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:702–713. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Wustenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, Wrase J, Heinz A. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2006;29:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsanis J, Iacono WG, Beiser M, Lacey L. Clinical correlates of anhedonia and perceptual aberration in first-episode patients with schizophrenia and affective disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101(1):184–191. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RSE, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;68:283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Kraepelin and the differential diagnosis of dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1986;27(6):549–558. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(86)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive insanity and paranoia. E. and S. Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Moran EK. Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: insights from affective science. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(5):819–834. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Elis O. Emotion deficits in people with schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:409–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loas G, Monestes JL, Ingelaere A, Noisette C, Herbener ES. Stability and relationships between trait or state anhedonia and schizophrenic symptoms in schizophrenia: a 13-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166(2-3):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M, Squillacioti MR, Pecora RD, Janiri L, Bria P. Effect of aripiprazole on self-reported anhedonia in bipolar depressed patients. Psychiatry Research. 2009;165(1-2):193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B, Johnson S, Winters R. Responsiveness to threat and incentive in bipolar disorder: relations of the BIS/BAS Scales with symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23(3):133–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1010929402770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak EE, Torres IJ, Bond BJ, Lam RW, Yatham LN. The relationship between clinical outcomes an quality of life in first-episode mania: a longitudinal analysis. Bipolar Disorders. 2013;15(2):188–198. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Sayers SL, Schooler NR, Mance RM, Haas GL. A multisite investigation of the reliability of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1453–1462. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Delespual PA, deVries MW. Schizophrenia patients are more emotionally active than is assumed based on their behavior. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26(4):847–854. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, van Os J, Schwartz JE, Stone AA, Delespual PA. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(12):1137–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, Abramson LY, Harmon-Jones E, Alloy LB, Hogan ME. Pre-goal attainment life event and the onset of bipolar episodes: perspective from the behavioral approach system dysregulation theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:105–115. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Goetz E, Ostacher M, Iosifescu DV, Perlis RH. Euthymic patients with bipolar disorder show decreased reward learning in a probabilistic reward task. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(2):162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa AR, Reinares M, Michalak EE, Bonnin CM, Sole B, Franco C, Comes M, Torrent C, Kapczinski F, Vieta E. Functional impairment and disability across mood states in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2010;13(8):984–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Curran PJ, Mueser KT. Factor structure and construct validity of the scale for the assessment of negative symptoms. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten MR, van Honk J, Aleman A, Kahn RS. Behavioral inhibition system (BIS), behavioral activation system (BAS) and schizophrenia: relationship with psychopathology and physiology. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürhoff F, Szöke A, Bellivier F, Turcas C, Villemur M, Tignol J, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a distinct familial subtype? Schizophrenia Research. 2003;61(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Manual (STAI) Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Wilbur RC, Warren KR, August SM, Gold JM. Anticipatory vs. consummatory pleasure: what is the nature of hedonic deficits in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Research. 2011;187(1-2):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP. The emotion paradox of anhedonia in schizophrenia: or is it? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013;39:247–250. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Waltz JA, Gold JM. A Review of Reward Processing and Motivational Impairment in Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt197. Advance access published December 27, 2013. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend J, Altshuler LL. Emotion processing and regulation in bipolar disorder: a review. Bipolar Disorders. 2012;14:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso IF, Grove TB, Taylor SF. Self-assessment of psychological stress in schizophrenia: preliminary evidence of reliability and validity. Psychiatry Research. 2012;195(1-2):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursu S, Kring AM, Gard MG, Minzenberg MJ, Yoon JH, Ragland JD, Solomon M, Carter CS. Prefrontal cortical deficits and impaired cognition-emotion interactions in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):276–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, MHS Staff . Social Adjustment Scale – Self-Report (SAS) Multi-Health Systems Inc.; Tonawanda, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. Wide Range Achievement Test 3 (WRAT3) Wide Range, Inc.; Wilmington, DE: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ziauddeen H, Murray GK. The relevance of reward pathways for schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2010;23:91–96. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336661b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]