Abstract

Background: little is known about changes in the quality of medical care for older adults over time.

Objective: to assess changes in technical quality of care over 6 years, and associations with participants' characteristics.

Design: a national cohort survey covering RAND Corporation-derived quality indicators (QIs) in face-to-face structured interviews in participants' households.

Participants: a total of 5,114 people aged 50 or more in four waves of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing.

Methods: the percentage achievement of 24 QIs in 10 general medical and geriatric clinical conditions was calculated for each time point, and associations with participants' characteristics were estimated using logistic regression.

Results: participants were eligible for 21,220 QIs. QI achievement for geriatric conditions (cataract, falls, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis) was 41% [95% confidence interval (CI): 38–44] in 2004–05 and 38% (36–39) in 2010–11. Achievement for general medical conditions (depression, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, pain and cerebrovascular disease) improved from 75% (73–77) in 2004–05 to 80% (79–82) in 2010–11. Achievement ranged from 89% for cerebrovascular disease to 34% for osteoarthritis. Overall achievement was lower for participants who were men, wealthier, infrequent alcohol drinkers, not obese and living alone.

Conclusion: substantial system-level shortfalls in quality of care for geriatric conditions persisted over 6 years, with relatively small and inconsistent variations in quality by participants' characteristics. The relative lack of variation by participants' characteristics suggests that quality improvement interventions may be more effective when directed at healthcare delivery systems rather than individuals.

Keywords: quality of care, geriatrics, epidemiology, older people

Introduction

Ten to fifteen years ago, patients in England and in the USA received little more than half of recommended care, with substantially worse care for ‘geriatric’ conditions associated with disability and frailty than for general medical conditions [1–3]. Subsequent initiatives to improve the quality of care, such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in the UK [4], have tended to exclude geriatric conditions despite strong evidence of effectiveness [5], with subsequent low quality of care [6–8]. Until now longitudinal cohort data on the quality of care received by older people with a range of participant characteristics, for both ‘geriatric’ and ‘general medical’ conditions, have been lacking. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) is the first national cohort study to measure quality of healthcare over time, alongside participants' characteristics.

We aimed to examine trends in quality of care from 2004 to 2011 for a range of common chronic conditions for people aged 50 or more and to compare quality of care for ‘general medical’ conditions with care for age-related ‘geriatric’ conditions. We also aimed to find out which participants' characteristics were associated with the receipt of better healthcare.

Methods

The ELSA sample was selected to be representative of adults aged 50 or more living in private households in England [9]. Four consecutive waves of ELSA in 2004–05, 2006–07, 2008–09 and 2010–11 used face-to-face interviews at participants' places of residence, with a nurse visit in 2004–05 and 2008–09. We included all participants who had been interviewed in four consecutive waves of ELSA.

ELSA collected data on receipt of public and privately provided healthcare, as well as on health and disability, health behaviour, biological markers of disease, economic circumstance, social participation, networks and well-being [9]. Questions of quality of care were derived from quality indicators (QIs) covering both general medical conditions such as diabetes (e.g. ‘IF a person aged 50 or older has diabetes, THEN his or her glycosylated haemoglobin or fructosamine level should be measured at least annually’) and conditions affecting predominantly older adults (e.g. ‘IF a person aged 65 or older reported 2 or more falls in the past year, or a single fall with injury requiring treatment, THEN the patient should be offered a multidisciplinary falls assessment’), as described elsewhere [10]. Repeated measures of quality of care were available for 24 clinical QIs in 10 medical conditions. We classified each of the 10 conditions as either general medical (cerebrovascular disease, depression, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and pain management) or geriatric (falls, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and cataract) [3]. Questions about cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and osteoarthritis were asked in every wave, and all conditions were covered in the baseline wave and one or more follow-up waves. The full set of QIs is summarised in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix Table S1. The focus was on effective care, rather than on the other important dimensions of quality, safety and patient experience.

Statistical analysis

The quality score for each indicator was that the number of times the indicator was achieved divided by the number of times it was triggered, expressed as a percentage, with possible values between 0 and 100%. Changes in quality indicator achievement over time were tested with a Chi-squared test for comparing proportions. Associations between participants' characteristics and quality of healthcare were tested with logistic regression models. For details of covariates and analysis, please see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix.

Results

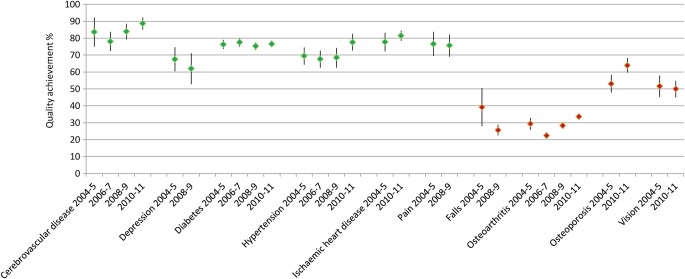

A total of 5,114 participants with a mean age of 65 years were interviewed in all four waves, of whom between 1,998 and 2,961 had at least one condition of interest in any one wave (Table 1). The response rate in 2004–05 was 82% [11, 12]. Achievement for geriatric conditions (cataract, falls, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis) was 41% in 2004–05 and 38% in 2010–11 (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix Table S2). Achievement for general medical conditions improved from 75% of eligible indicators in 2004–05 to 80% in 2010–11. Overall, quality indicator achievement dropped slightly from 59% in 2004–05 to 54% in 2010–11. Receipt of indicated care in 2010–11 varied substantially by condition and ranged from 89% for cerebrovascular disease to 34% for osteoarthritis (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix Table S3 and Figure 1). Achievement rates for individual QIs are given in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix Table S1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 5,114 participants who were interviewed in all four waves

| Characteristic | 2004–05 | 2006–07 | 2008–09 | 2010–11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||||

| Mean | 64.8 | 66.6 | 68.7 | 70.9 |

| Rangea | 52 to >90 | 54 to >90 | 56 to >90 | 58 to >90 |

| Female, n (%) | 2,882 (56.4) | No change | No change | No change |

| Male, n (%) | 2,232 (43.6) | |||

| White, n %) | 5,026 (98.3) | No change | No change | No change |

| Non-white, n (%) | 86 (1.7) | |||

| Educationb (highest qualification), n (%) | No change | No change | No change | |

| Higher education | 1,449 (28.3) | |||

| High school | 2,004 (39.2) | |||

| No qualifications | 1,660 (32.5) | |||

| Total net household financial wealth (£) | ||||

| Median | 208,664 | 230,406 | 226,242 | 231,365 |

| Range | −43,470–9,297,227 | −83,903–208 × 105 | −150,171–208 × 105 | −92,902–6,557,635 |

| One or more conditions, n (%) | 1,998 (39) | 2,738 (54) | 2,961 (58) | 2,290 (44.8) |

| Number of conditions for which participants were eligible | ||||

| Meanc | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Range | 0–6 | 0–4 | 0–4 | 0–3 |

| Number of indicators for which participants were eligible | ||||

| Meanc | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Range | 0–13 | 0–7 | 0–8 | 0–8 |

| Clinical incidenced over 2 years, n (%) | ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 32 (0.7) | 53 (1.1) | 60 (1.2) | |

| Depression | 65 (1.3) | 53 (1.1) | ||

| Falls | 254 (5.0) | |||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 183 (3.7) | |||

| Osteoarthritis | 415 (11.1) | 372 (9.7) | 415 (11.1) | |

| Pain | 80 (1.6) | |||

| Hypertension | 253 (8.5) | 453 (13.5) | 334 (10.7) | |

| Clinical prevalence, n (%) | ||||

| Osteoporosis | 295 (5.8) | 338 (6.6) | 395 (7.7) | 475 (9.3) |

| Cataract | 512 (10.0) | 803 (15.7) | 875 (17.1) | 1,095 (21.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 351 (6.9) | 447 (8.7) | 542 (10.6) | 634 (12.4) |

aAll 95 respondents with age >90 years had exact age withheld from released data.

bHigher education = degree or higher education below degree; high school = secondary school or equivalent. Information was missing on education for one participant.

cRounded to nearest whole number.

dIncidence rates refer to ∼2 years since the previous survey wave or have been adjusted for 2 years.

Figure 1.

Quality indicator achievement and 95% CIs by condition and year. General medical conditions on the left of the chart (cerebrovascular disease to pain). Geriatric conditions on the right of chart (falls to vision).

Regression analysis

There were 21,220 eligible QIs in all four waves combined. We found few significant associations with overall quality of care for most participant characteristics. The exceptions, where we found significant associations, were sex, wealth, body mass index (BMI), alcohol intake and co-habitation status. The odds of QI achievement in men compared with women was 0.7, in the wealthiest fifth of participants compared with the poorest fifth was 0.8 and in regular (compared with infrequent) drinkers was 0.8 (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix Table S4). Obese participants (BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more) had 1.5 times higher odds of QI achievement than those with low or normal BMI, and those living alone had higher odds than those living with a partner (1.2). There were few statistically significant results for quality indicator achievement at the level of individual conditions rather than overall, and the size and direction of effect differed between conditions (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix Table S5 and details of covariates and analysis).

Discussion

Quality of care for adults aged 50 or more in England changed remarkably little over 6 years, with a slight overall worsening of quality despite quality improvement initiatives. Achievement of QIs for geriatric conditions was only half as good as for general medical conditions, and this large gap in care has persisted and widened slightly over 6 years of follow-up from 2004–05 to 2010–11. Women, those living alone, infrequent drinkers and poorer or more obese participants received better care overall, but differences in the participants' characteristics that were associated with the quality of care for individual conditions were generally small and inconsistent.

This is the first national cohort study to measure quality of care for a range of common chronic conditions, with individual level data on a wide range of participants' characteristics. This paper describes only 24 QIs in 10 conditions which, although the conditions and indicated care are common, can only represent a proportion of all care provided. Changes in care for conditions not covered in ELSA may have followed a different pattern. However, ELSA measured more indicators of quality of care over a longer period of time than other studies. The QIs were developed through a rigorous process, and improved achievement of them is associated with improved health outcomes [13]. All diagnoses and quality of care measures were self-reported at interviews, which may be a less reliable source than medical records, although concordance between self-reports and medical records can be good, with self-reports tending to score the same or higher than medical records [14, 15].

Future quality improvement initiatives should pay as much attention to quality of care for age-related medical conditions as to the general medical conditions that have traditionally been the focus of medical quality improvement campaigns. The relatively small variations in QI achievement by other participant characteristics suggest that, although high-quality equitable care for many conditions is widespread, the system-level deficits in the provision of care for ‘geriatric’ conditions are getting worse and need attention.

Many different models have the potential to improve the quality of care for people with common conditions associated with ageing, with common features being strong generalist or primary care, and the use of care plans and complete electronic medical records to improve continuity of care [16, 17]. Promising models need to be extensively tested in specific healthcare contexts and embedded in routine clinical care if successful.

Key points.

System-level shortfalls in quality for geriatric conditions have persisted over 6 years.

Care was usually delivered equitably to participants with different characteristics.

Future quality improvement initiatives for geriatric conditions could focus on system-level interventions.

Authors’ contributions

N.S. contributed to the study design, oversaw data analysis and interpretation and drafted the paper. N.S. is guarantor. A.C.H. undertook data preparation, analysis and interpretation, and contributed to drafting the paper. L.T.A.M. undertook data preparation and analysis. M.O.B., A.C. and W.E.H. advised on statistical techniques. S.H.R. undertook data checking and advised on data analysis and interpretation. J.L.C. advised on data analysis and interpretation. D.M. contributed to the study design and advised on data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to data interpretation and revised the paper critically.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Data sharing

Full ELSA data are available from the UK Data Service at http://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/catalogue?sn=5050 (27 June 2014, date last accessed) with open access.

Ethical approval

ELSA received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service: 09/H0505/124. Participants gave informed consent before taking part.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (grant number HS&DR Project 10/2002/06). The ELSA was funded by the US National Institute on Aging and UK government departments. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report or decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements

This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Health Services Research programme. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. Dave Stott and Amander Wellings, representatives of Public and Patient Involvement in Research (PPIRes), brought a helpful lay perspective to this research, including specific comments on earlier versions of this paper.

References

- 1.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:740–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steel N, Bachmann M, Maisey S, et al. Self reported receipt of care consistent with 32 quality indicators: National population survey of adults aged 50 or more in England. BMJ. 2008;337:a957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS Employers and the General Practitioners Committee. Quality and Outcomes Framework for 2012/13. Guidance for PCOs and Practices. London: NHS Employers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Khoury F, Cassou B, Charles M, Dargent-Molina P. The effect of fall prevention exercise programmes on fall induced injuries in community dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f6234. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillam SJ, Siriwardena AN, Steel N. Pay-for-performance in the United Kingdom: impact of the Quality and Outcomes Framework—a systematic review. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:461–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell SM, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Sibbald B, Roland M. Effects of pay for performance on the quality of primary care in England. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:368–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steel N, Maisey S, Clark A, Fleetcroft R, Howe A. Quality of clinical primary care and targeted incentive payments: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:449–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banks J, Nazroo J, Steptoe A. The Dynamics of Ageing: Evidence From the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing 2002–10 (Wave 5) London: Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steel N, Melzer D, Shekelle PG, Wenger NS, Forsyth D, McWilliams BC. Developing quality indicators for older adults: transfer from the USA to the UK is feasible. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13:260–4. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banks J, Breeze E, Lessof C, Nazroo J. Retirement, Health and Relationships of the Older Population in England: The 2004 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (Wave 2) London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesire H, Hussey D, Medina J, et al. London: National Centre for Social Research; 2012. Financial Circumstances, Health and Well-being of the Older Population in England: The 2008 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Wave 4 Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min LC, Reuben DB, Adams J, et al. Does better quality of care for falls and urinary incontinence result in better participant-reported outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1435–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tisnado DM, Adams JL, Liu H, et al. What is the concordance between the medical record and patient self-report as data sources for ambulatory care? Med Care. 2006;44:132–40. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196952.15921.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang JT, MacLean CH, Roth CP, Wenger NS. A comparison of the quality of medical care measured by interview and medical record. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(Supplement (abstract)):109–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, Pacala JT, Snyder C, Leff B. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the institute of medicine’s ‘retooling for an Aging America’ report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2328–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornwell J, Levenson R, Sonola L, Poteliakhoff E. Continuity of Care for Older Hospital Patients: A Call for Action. London: The King’s Fund; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.