ABSTRACT

There has been an accumulation of information on frequencies of insertion/deletion (indel) polymorphisms within the bovine prion protein gene (PRNP) and on the number of octapeptide repeats and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the coding region of bovine PRNP related to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) susceptibility. We investigated the frequencies of 23-bp indel polymorphism in the promoter region (23indel) and 12-bp indel polymorphism in intron 1 region (12indel), octapeptide repeat polymorphisms and SNPs in the bovine PRNP of cattle and water buffaloes in Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand. The frequency of the deletion allele in the 23indel site was significantly low in cattle of Indonesia and Thailand and water buffaloes. The deletion allele frequency in the 12indel site was significantly low in all of the cattle and buffaloes categorized in each subgroup. In both indel sites, the deletion allele has been reported to be associated with susceptibility to classical BSE. In some Indonesian local cattle breeds, the frequency of the allele with 5 octapeptide repeats was significantly high despite the fact that the allele with 6 octapeptide repeats has been reported to be most frequent in many breeds of cattle. Four SNPs observed in Indonesian local cattle have not been reported for domestic cattle. This study provided information on PRNP of livestock in these Southeast Asian countries.

Keywords: BSE, indel polymorphisms, local cattle, PRNP, SNPs, Southeast Asia

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) in mammals are caused by abnormally folded prion proteins that induce conversion of the normal and noninfectious cellular form of the host prion protein (PrPC) into an abnormal and infectious form (PrPSc) [21]. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is a TSE of cattle, which is transmitted to humans via consumption of BSE-contaminated beef and causes the development of a variant type of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) [9]. Susceptibility or resistance to TSEs can be influenced by several factors of the host prion protein, such as specific amino acid polymorphisms, number of octapeptide repeats present and prion protein expression levels. Amino acid mutations in the prion protein are major factors influencing susceptibility and resistance to TSEs in humans and sheep. Susceptibility to BSE may also be enhanced by bovine PrPC having 7 or more octapeptide repeats, though only Brown Swiss cattle have been shown to have 7 octapeptide repeats [3, 10].

In general, it is hypothesized that frequencies of insertion/deletion (indel) polymorphisms at two non-coding regions of bovine PRNP, 23indel and 12indel sites, are associated with PrPC expression levels [23]. The first polymorphism is a 23-bp deletion (23del) within the upper region of the promoter that removes a binding site for the RP58 repressor protein, and the second is a 12-bp deletion (12del) within intron 1 that removes an SP1 transcription factor binding site. A reporter gene assay demonstrated an interaction between the two postulated transcription factors and lower expression levels of the 23-bp insertion (23ins)/12-bp insertion (12ins) allele compared with the 23del/12del allele [23]. Cattle possessing these deletions and therefore lacking binding sites for their respective regulatory elements have been reported to be more susceptible to classical BSE [12, 24], but these polymorphisms do not influence resistance to atypical BSE [2, 6]. Based on results of molecular weight analysis, atypical BSE can be divided into two subtypes: a subtype with a lower molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrPSc isoform (L-type) and a subtype with a higher molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrPSc isoform (H-type). An amino acid replacement at codon 211 (glutamic acid to lysine, E211K) encoded by bovine PRNP has been reported in a few H-type atypical BSE cases [19, 22]. The E211K change is analogous to the human E200K amino acid replacement, which is a trigger of the development of heritable human TSE [8]. Recently, new information regarding the frequency and distribution of bovine PRNP indel polymorphisms has been reported for Vietnamese local cattle and native Chinese cattle [17, 27, 29], and the information suggests that Asian local breed cattle have a variety of genetic divergences within the PRNP for potential association with BSE.

In order to obtain information on PRNP in Southeast Asian cattle and water buffalo, we investigated PRNP polymorphisms of cattle and water buffalo in Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

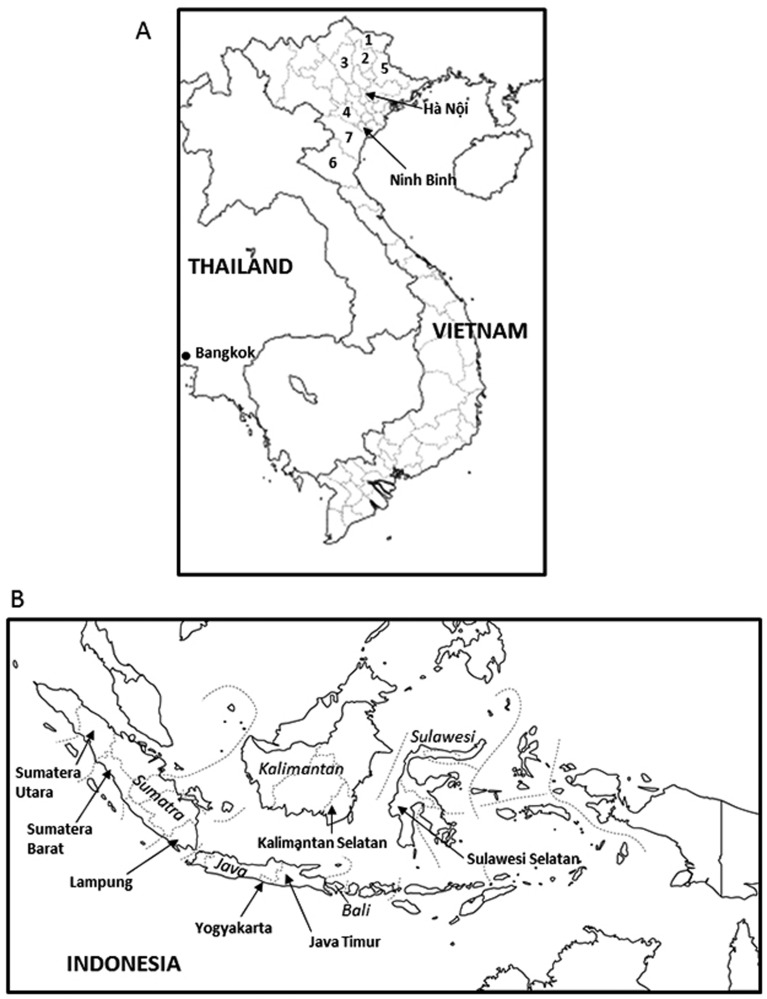

Genomic DNA samples from cattle and water buffalo in Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia: We collected liver or spleen samples from 288 cattle (Bos taurus and B. indicus) and 60 water buffalo (Swamp buffalo, Bubalus bubalis) in Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Vietnamese samples were collected from nine provinces in the northern part of Vietnam at the period from July to August in 2007. Indonesian samples were collected from seven provinces in March 2007. For the Thai samples, we bought spleens of cattle and water buffalo at several grocery stores belonging to three different logistic groups in Bangkok in December 2005. All of the bovine liver and spleen samples were subjected to extraction of genomic DNA as described elsewhere [17]. The extracted DNA solutions were stored at −30°C until use.

Table 1. Bovinae animals used for this study.

| Countries (total heads) | Sampling areasa) | Species or breedb) (subtotal heads) |

|---|---|---|

| Vietnam (100) | Cao Bằng | Local cattle (36), Water buffalo (1) |

| Bắc Kạn | Local cattle (8) | |

| Tuyên Quang, Hòa Bình | Local cattle (5, each) | |

| Lạng Sơn | Local cattle (2) | |

| Hà Nội | Local cattle (15) | |

| Nghệ An | Local cattle (6) | |

| Ninh Binh, Thanh Hóa | Local cattle (11, each) | |

| Indonesia (135) | Sumatra Utara | Brahman cross (6), Local cattle (14) |

| Sumatra Barat | UN (18) | |

| Lampung | Local cattle (2), Bali cattle (1), Limousin (2), UN (13), Water buffalo (2) | |

| Sulawesi Selatan | Peranakan Ongole (13), Limousin (2), Brahman (1), Simmental (4) | |

| Kalimantan Selatan | Local cattle (11), Water buffalo (6) | |

| Java Timur | Bali cattle (20) | |

| Yogyakarta | Bali cattle (13), Brahman (1), Water buffalo (6) | |

| Thailand (113) | Bangkok | Local cattle (68), Water buffalo (45) |

a) In Vietnam and Indonesia, each name of the sampling area means that of a province. Bangkok is the name of the capital city of Thailand. b) Vietnamese local cattle group consisted of Vietnamese Yellow local cattle and their cross breeds. UN means unknown cattle breed.

Fig. 1.

Sampling areas in Vietnam and Thailand (Panel A) and in Indonesia (Panel B). A: Vietnamese samples (99 cattle and 1 water buffalo) were collected from nine provinces in the northern part of Vietnam (nos. 1 to 7, Hà Nội and Ninh Binh). Numbers indicate the names of provinces. 1, Cao Bằng; 2, Bắc Kạn; 3, Tuyên Quang; 4, Hòa Bình; 5, Lạng Sơn; 6, Nghệ An; and 7, Thanh Hóa. Thai samples (68 cattle and 45 water buffaloes) were bought at several grocery stores in Bangkok. B: Indonesian samples were collected from seven provinces (Sumatra Utara, Sumatra Barat, Lampung, Yogyakarta, Java Timur, Kalimantan Selatan and Sulawesi Selatan). The names of islands from which samples were collected in Indonesia are shown in italics.

PCR and sequencing analyses: The extracted DNA solutions were used for PCR assays to determine the frequencies of polymorphisms within the 23indel, 12indel and octapeptide repeat regions of bovine PRNP. The primers pair 23F-23R was used for genotyping 23indel, and the primers pair 12F-12R was used for genotyping 12indel in each PCR assay [2]. We designed the primer pair OctF (5′-GCAACCGTTATCCACCTCAG-3′) and OctR 5′-TGGCTTACTGGGTTTGTTCC-3′) for PCR to amplify the octapeptide repeat region on the basis of the sequence data obtained from GenBank (Acc. No. AJ298878). The entire coding region of PRNP was amplified as two fragments by PCR using the primer pairs F1-R2 and F2-R1 [2]. PCRs for the above four regions were performed with the following conditions of amplification: 2 min at 94°C followed by 13 cycles of 30 sec each at 94°C, 65°C and 72°C with stepwise lowering of the annealing temperature from 65°C to 55.4°C by the 13th cycle; and 23 cycles of 30 sec each at 94°C, 52°C and 72°C, followed by incubation at 72°C for 5 min as a final extension step. DNA sequencing was carried out for the PCR products of the entire coding region of PRNP. Purification of the PCR products for sequencing was done using a SUPRECTM- PCR (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). When the PCR products were heterozygous for octapeptide repeats in the coding region, the 5-repeat and the 6-repeat fragments were individually recovered by using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). DNA sequencing was carried out in both directions on an ABI PRISMTM 310 Genetic Analyzer using a BigDye® Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Nucleic acid sequences were assembled and edited by using sequence alignment editing software (BioEdit version 7.0.5, http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html).

Statistical analyses: We categorized all Bovinae animals into 5 groups, Vietnamese cattle, Indonesian cattle, Thai cattle, Indonesian water buffaloes and Thai water buffaloes, to determine whether the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was applicable to the population in each group. Then, in the 23indel and 12indel polymorphisms, haplotype frequencies were derived from the genotypic data. The test of HWE and the haplotype estimation were performed by using gene analysis software, Haploview 4.2 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/scientific-community/science/programs/medical-and-population-genetics/haploview/haploview). Differences in frequency distributions of allele, genotype and haplotype were calculated with Fisher’s exact test by using the freely available statistical software ‘EZR’ (version 1.00; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for the free statistical software ‘R’ (version 2.13.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) [13]. For comparison of allelic and genotypic polymorphism frequencies in the 2 indel sites and haplotype frequency, the following three cattle groups and one water buffalo group were used as reference groups: UK healthy and BSE-affected Holstein Friesian cattle [12], B. indicus of five breeds [3] and Anatolian water buffalo (B. bubalis) [20]. German healthy and BSE-affected cattle [24] were used as reference groups for comparison of allelic and genotypic polymorphism frequencies among octapeptide repeat polymorphisms. Because of the variety of cattle breeds and species, we compared the frequencies of 23indel, 12indel, haplotype and octapeptide repeat polymorphisms in subgroups of Indonesian local cattle with those of the reference groups. For comparison among the subgroups of Indonesian local cattle, information for subgroups with less than 10 head of cattle was excluded, because the numbers of cattle in these subgroups were too small for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

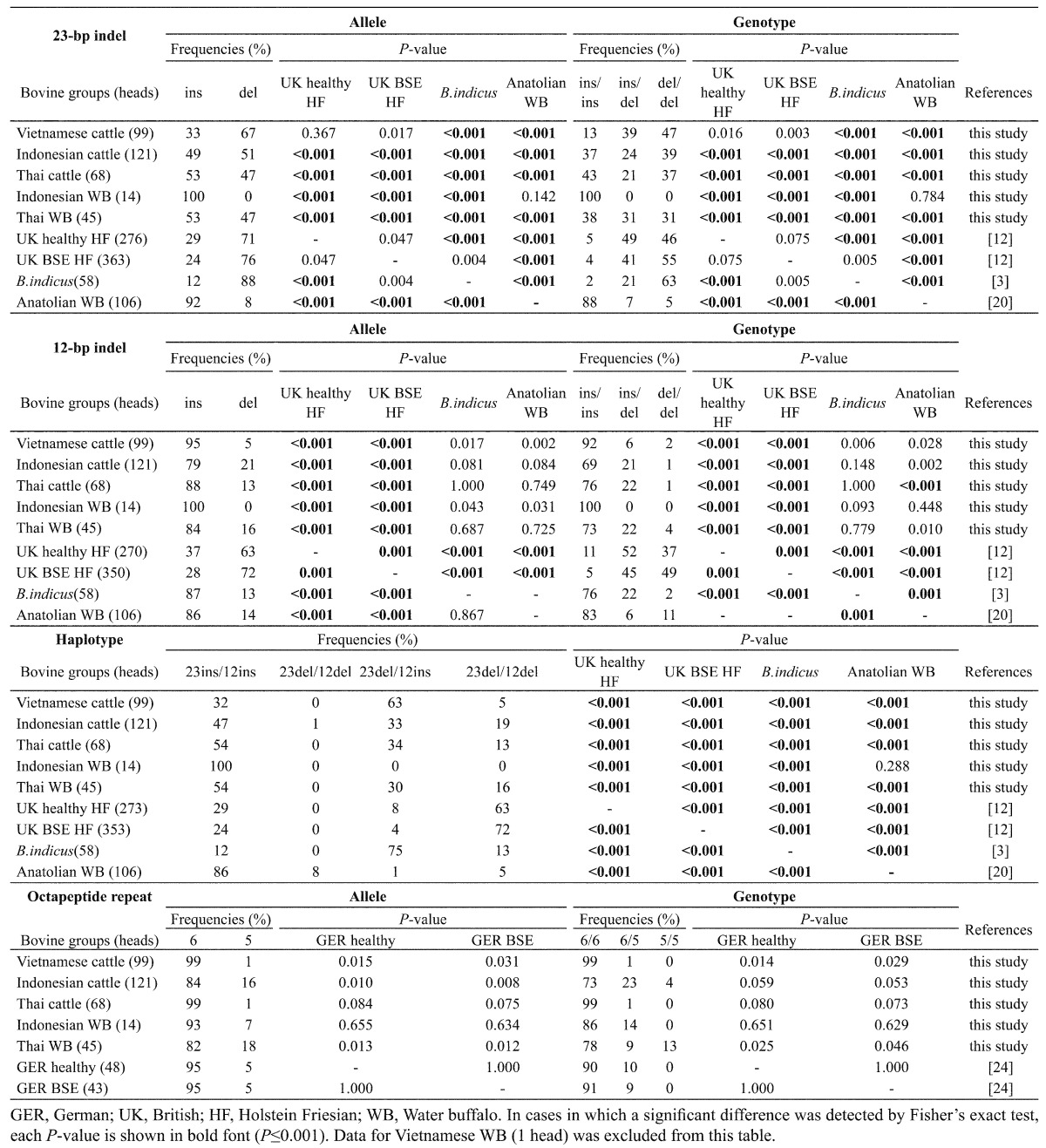

23indel, 12indel, haplotype and octapeptide repeat polymorphisms (Table 2 ): The frequency distributions of alleles and genotypes in the 23indel site of Indonesian cattle and Thai cattle were significantly lower than those of all of the reference cattle groups. However, a significant difference in the frequency distribution of alleles or genotypes in the 23indel site was not found between Vietnamese cattle and the UK reference cattle groups. In the 12indel site of cattle, the frequency distributions were clustered on the ins allele and the ins/ins genotype. The frequencies of the 12del allele and del/del genotype of the cattle of all three countries were significantly lower than those of the UK reference cattle groups.

Table 2. Distributions of allele and genotype frequencies for 23-bp indel, 12-bp indel and octapeptide repeat polymorphisms in PRNP of the bovidae animals examined in this study.

All of the cattle groups of the three countries showed significant differences in the frequency distributions of haplotype polymorphisms against all of the reference groups, but the major haplotype of Vietnamese cattle was different from those of the other 2 countries. The frequencies of 23del-12del in cattle of all 3 countries were significantly lower than those in the UK reference cattle groups. The HWE was applicable to all populations for both indel polymorphisms.

In the Indonesian water buffaloes, the frequency distributions of polymorphisms in all items (indel sites, haplotype and octapeptide repeats) were similar to those of Anatolian water buffaloes. On the other hand, Thai water buffaloes showed polymorphic patterns of frequency distributions similar to those of the frequency distributions in Thai cattle for all items. We excluded information for the Vietnamese water buffalo from Table 2, because we tested only one water buffalo in Vietnam in this study. The genotype and octapeptide repeat polymorphisms of the Vietnamese water buffalo tested were ins/ins in both indel sites and 6/6. A significant difference between observed bovine data and reference data was not detected in octapeptide repeat polymorphism. Seven or more repeats were not detected in our study.

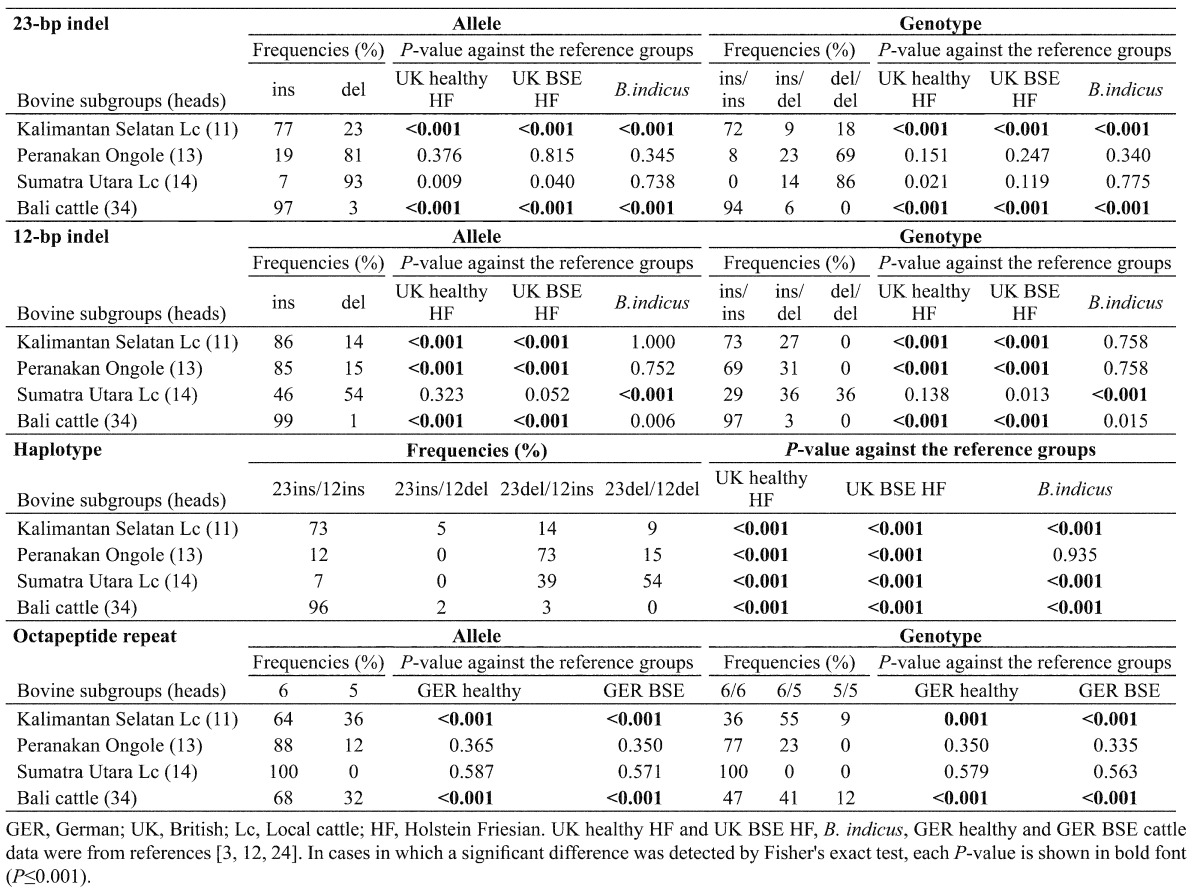

Frequencies of 23indel, 12indel, haplotype and octapeptide repeat polymorphisms in subgroups of Indonesian local cattle (Table 3 ): In the Kalimantan Selatan local cattle and Bali cattle, frequencies of the del allele and del/del genotype in both indel sites were significantly lower than those in all of the reference cattle groups. Significant differences in frequencies of the 12indel site were found between Peranakan Ongole breed cattle and the UK reference groups and between Sumatra Utara breed cattle and B. indicus, respectively. The major haplotypes were 23ins-12ins in Kalimantan Selatan local cattle and Bali cattle, 23del-12ins in Peranakan Ongole breed and 23del-12del in Sumatra Utara local cattle. Haplotype 23ins-12del was minor or was not detected. The frequencies of 23del-12del were significantly lower in all cattle subgroups except Sumatra Utara local cattle than in the reference groups. The frequencies of 23ins-12ins were significantly higher in Kalimantan Selatan local cattle and Bali cattle than in the reference groups. For all of the tested subgroups, the HWE was applicable for the 12indel polymorphism, but was not applicable for the 23indel polymorphism. As for the frequency of octapeptide repeat polymorphism, only two subgroups (Kalimantan Selatan local cattle and Bali cattle) showed a significant difference from the reference groups.

Table 3. Distributions of allele and genotype frequencies for 23-bp indel, 12-bp indel and octapeptide repeat polymorphisms in PRNP among subgroups of Indonesian local cattle.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the coding region of PRNP (Table 4): A total of 15 SNPs were detected in the coding region of PRNP in 85 cattle DNA samples selected from the three countries. All of the genotypes for octapeptide repeat polymorphism (6/6, 6/5 and 5/5) were included in the selected samples. Numbering of each nucleotide and amino acid position refers to the sequence of Bali cattle obtained in this study (GenBank accession no. AB761619). Three sites at nucleotide positions 8 (A to C), 461 (G to A) and 554 (A to G) were non-silent mutations. These SNPs corresponded to the following amino acid substitutions: lysine to threonine (K3T), serine to asparagine (S154N) and asparagine to serine (N185S). Of the remaining 12 SNPs that showed silent mutations, four sites at positions 108 (T to G), 267 (T to A), 554 (A to G) and 783 (C to T) were unique to Indonesian cattle, particularly Kalimantan Selatan local cattle and Bali cattle. These 4 SNPs have not yet been reported for domestic cattle, and nucleotide mutation at position 783 (C to T) is known only for Banteng (B. javanicus) [26]. There was no PRNP allele in our samples that exhibited E211K amino acid replacement, which is considered to be a possible cause of H-type atypical BSE.

Table 4. SNPs in the coding region of bovine PRNP detected in this study.

| Countries | Cattle species or breeds (heads) | Polymorphic nucleotide positions (nucleotide mutaions)a) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam | Vietnamese local cattle (24) | 8 (A to C) | 69 (C to T) | 75 (G to A) | 108 (T to A) | 126 (A to G) | 234 (G to A) |

| 357 (C to T) | 461 (G to A) | 555 (C to T) | 630 (C to T) | 675 (C to T) | 678 (T to C) | ||

| Indonesia | Sumatra Utara local cattle (2), | 69 (C to T) | 108 (T to G) | 126 (A to G) | 234 (G to A) | 267 (T to A) | 555 (C to T) |

| Peranakan Ongole (3), Unkown (4) | 630 (C to T) | 678 (T to C) | 783 (C to T) | ||||

| Kalimantan Selatan local cattle (11) | 8 (A to C) | 108 (T to G, T to A) | 126 (A to G) | 234 (G to A) | 267 (T to A) | 461 (G to A) | |

| 554 (A to G) | 555 (C to T) | 678 (T to C) | 783 (C to T) | ||||

| Bali cattle (34) | 108 (T to G) | 126 (A to G) | 234 (G to A) | 267 (T to A) | 461 (G to A) | 554 (A to G) | |

| 555 (C to T) | 630 (C to T) | 678 (T to C) | 783 (C to T) | ||||

| Thailand | Thai local cattle (7) | 108 (T to A) | 126 (A to G) | 234 (G to A) | 461 (G to A) | 555 (C to T) | 630 (C to T) |

| 675 (C to T) | 678 (T to C) | ||||||

a) Bold nucleotide positions are predicted to result in amino acid replacements. All others represent synonymous mutation. Amino acid replacements provided by SNPs are as follows: 8 (A to C) (K3T), 461 (G to A) (S154N) and 554 (A to G) (N185S). Nucleotide positions and mutations underlined have not yet been reported for domestic cattle. Numbering was derived from the six-octapeptide cattle allele. Nucleotide positions refer to GenBank AJ298878.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide information on PRNP of livestock in these Southeast Asian countries. Significantly lower frequencies of the del polymorphism in the 23indel site were found in cattle in Indonesia and Thailand, and significantly lower frequencies of the del polymorphism in the 12indel site were found in cattle in all three countries. In contrast, the distributions of 23del polymorphisms in Vietnamese cattle showed a tendency to be similar to those in the UK reference cattle groups. The breeding history of Vietnamese cattle may have contributed to the distributional similarity. In Vietnam, more than 80% of dairy cattle are cross-bred between Holstein Friesian cattle and local Yellow cattle and Red Sindhi, a B. indicus breed introduced to Vietnam at the beginning of the 20th Century [1, 28].

The frequency patterns of 2 indel polymorphisms in Indonesian cattle and Thai cattle, especially Bali cattle and Kalimantan Selatan local cattle in Indonesia, do not conform to any of those previously reported for domestic cattle. These unique genetic backgrounds of PRNP probably originated from their ancestral animals. Bali cattle are generally recognized as domesticated cattle from wild Banteng. Bali cattle are different from all other species of cattle as a result of difference in their origin and evolution. B. taurus (European breed) and B. indicus (Zebu breed) are known to have been divided from a common ancestor, Aurochs (Bos primigenius), more than 3 million years ago. In contrast, restriction fragment length polymorphisms of mitochondrial DNA and the sequences of mitochondrial genes for cytochrome b confirmed that B. javanicus had a different ancestor from that of both B. taurus and B. indicus [14]. Moreover, a wide gene flow from B. javanicus extends to Southeast Asian local cattle to varying degrees [18]. It is notable that the del allele frequencies of two indel polymorphisms were low in Bali cattle, and our results suggested that both 23del and 12del polymorphisms are nonexistent or very few in B. javanicus and the ancestral animal of Southeast Asian local cattle.

An association between haplotype frequency for indel polymorphisms and BSE susceptibility has been reported in some domestic cattle breeds of B. taurus [7, 12]. The haplotype 23del-12del, which is associated with BSE incidence, is common in B. taurus, while the haplotype 23ins-12ins is the major haplotype in Indonesian and Thai cattle and in water buffalo. Functional studies of the promoter region of bovine PRNP indicated that 12del results in a significantly low level of PRNP expression compared with that in the case of 12ins [23]. However, the frequency of 12del allele is higher in the population of BSE-affected cattle, because the 12indel site is in strong linkage disequilibrium with the polymorphism in the 23indel site of PRNP [11, 12, 23, 29]. The 12indel polymorphism of bovine PRNP contains a putative binding region of SP1, which activates a wide range of viral and cellular genes. The 23-bp insertion leads to strong and specific binding with RP58, which represses transcription by interfering with the DNA-binding activity of SP1 [15]. Therefore, PRNP expression level is lower in the haplotype 23ins-12ins than in the haplotype 23del-12del owing to the repressive effect of the haplotype 23ins-12ins [23].

Although an association between octapeptide repeat polymorphism of bovine PRNP and typical BSE incidence has not been reported in cattle, transgenic mice expressing bovine PrPC of which the coding region contains 7 or 10 repeats have been reported to be more susceptible to BSE inoculums [4, 5]. While most domestic cattle have 5 or 6 octapeptide repeats [3, 24, 27, 29], seven repeats were reported in at least 5% of Brown Swiss breed [25] and 4 repeats were identified in an animal of B. indicus × B. taurus composite cattle and 2 domesticated cattle from wild Gaur (Bos gaurus) in Asia, named Mythun [26, 27]. In this study, an abnormal number of octapeptide repeats was not detected, but frequencies of the octapeptide repeat in Bali cattle and Kalimantan Selatan local cattle showed genetic differences from those of B. taurus and B. indicus.

In this study, we detected three non-silent mutations: lysine to threonine (K3T), serine to asparagine (S154N) and asparagine to serine (N185S). The mutation of K3T, which is located in a signal sequence of PrP, has been reported to be present in at least 6% of native Chinese cattle [29]. Our results suggested the probability of genetic interchange among Vietnamese local cattle, Kalimantan Selatan local cattle and native Chinese cattle. On the other hand, the mutation of S154N, which is located close to the first α-helix [16], is a very minor amino acid replacement in domestic cattle. The replacement has been observed in all alleles for a wide variety of Bovinae animals (Lesser kudu, Nilgai, Asian water buffalo, Lowland anoa, African buffalo and Forest buffalo) [26]. The mutation of N185S, which is located within the second α-helix [16], has not been reported in domestic cattle, but has been confirmed in B. javanicus and African buffalo [26]. There has been no report showing an association between the 3 non-silent mutations and BSE susceptibility. We detected several mutations that were reported in B. javanicus. The similarity between Bali cattle and B. javanicus in PRNP polymorphisms supports the hypothesis that Bali cattle are domesticated from B. javanicus, and our results suggest that the genetic diversity of PRNP in Indonesian local cattle is a result of gene flow from B. javanicus.

Our results suggest that Southeast Asian cattle and water buffaloes have low susceptibility to BSE, particularly to classical BSE. In Southeast Asian countries where crossbreeding with B. taurus and B. indicus has been increasing, selective improvement in local cattle is important as an approach to provide additional protection against BSE infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid to Cooperative Research (Rakuno Gakuen University Dairy Science Institute, 2009-6), a Support Project to Assist Private Universities in Developing Bases for Research, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (grant no. 17405044) and the Program of Founding Research Centers for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, from the MEXT, Japan. This work was also supported by a grant from the MHLW, Japan (grant no. 20330701).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashbaugh H. R.2010. A descriptive survey of dairy farmers in Vinh Thinh Commune, Vietnam. pp. 9–11. In: Public Health. Ohio State University, Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunelle B. W., Hamir A. N., Baron T., Biacabe A. G., Richt J. A., Kunkle R. A., Cutlip R. C., Miller J. M., Nicholson E. M.2007. Polymorphisms of the prion gene promoter region that influence classical bovine spongiform encephalopathy susceptibility are not applicable to other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 85: 3142–3147. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunelle B. W., Greenlee J. J., Seabury C. M., Brown C. E., 2nd, Nicholson E. M.2008. Frequencies of polymorphisms associated with BSE resistance differ significantly between Bos taurus, Bos indicus, and composite cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 4: 36. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-4-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castilla J., Gutierrez-Adan A., Brun A., Pintado B., Parra B., Ramirez M. A., Salguero F. J., Diaz San Segundo F., Rabano A., Cano M. J., Torres J. M.2004. Different behavior toward bovine spongiform encephalopathy infection of bovine prion protein transgenic mice with one extra repeat octapeptide insert mutation. J. Neurosci. 24: 2156–2164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3811-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castilla J., Gutierrez-Adan A., Brun A., Pintado B., Salguero F. J., Parra B., Segundo F. D., Ramirez M. A., Rabano A., Cano M. J., Torres J. M.2005. Transgenic mice expressing bovine PrP with a four extra repeat octapeptide insert mutation show a spontaneous, non-transmissible, neurodegenerative disease and an expedited course of BSE infection. FEBS Lett. 579: 6237–6246. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clawson M. L., Richt J. A., Baron T., Biacabe A. G., Czub S., Heaton M. P., Smith T. P., Laegreid W. W.2008. Association of a bovine prion gene haplotype with atypical BSE. PLoS One 3: e1830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haase B., Doherr M. G., Seuberlich T., Drogemuller C., Dolf G., Nicken P., Schiebel K., Ziegler U., Groschup M. H., Zurbriggen A., Leeb T.2007. PRNP promoter polymorphisms are associated with BSE susceptibility in Swiss and German cattle. BMC Genet. 8: 15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heaton M. P., Keele J. W., Harhay G. P., Richt J. A., Koohmaraie M., Wheeler T. L., Shackelford S. D., Casas E., King D. A., Sonstegard T. S., Van Tassell C. P., Neibergs H. L., Chase C. C., Jr, Kalbfleisch T. S., Smith T. P. L., Clawson M. L., Laegreid W. W.2008. Prevalence of the prion protein gene E211K variant in U.S. cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 4: 25. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill A. F., Desbruslais M., Joiner S., Sidle K. C., Gowland I., Collinge J., Doey L. J., Lantos P.1997. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature 389: 448–450. doi: 10.1038/38925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter N., Goldmann W., Smith G., Hope J.1994. Frequencies of PrP gene variants in healthy cattle and cattle with BSE in Scotland. Vet. Rec. 135: 400–403. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.17.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong B. H., Lee Y. J., Kim N. H., Carp R. I., Kim Y. S.2006. Genotype distribution of the prion protein gene (PRNP) promoter polymorphisms in Korean cattle. Genome 49: 1539–1544. doi: 10.1139/g06-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juling K., Schwarzenbacher H., Williams J. L., Fries R.2006. A major genetic component of BSE susceptibility. BMC Biol. 4: 33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanda Y.2013. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48: 452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikkawa Y., Amano T., Suzuki H.1995. Analysis of genetic diversity of domestic cattle in east and Southeast Asia in terms of variations in restriction sites and sequences of mitochondrial DNA. Biochem. Genet. 33: 51–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00554558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee D. K., Suh D., Edenberg H. J., Hur M. W.2002. POZ domain transcription factor, FBI-1, represses transcription of ADH5/FDH by interacting with the zinc finger and interfering with DNA binding activity of Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 26761–26768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202078200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López Garcia F., Zahn R., Riek R., Wuthrich K.2000. NMR structure of the bovine prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97: 8334–8339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muramatsu Y., Sakemi Y., Horiuchi M., Ogawa T., Suzuki K., Kanameda M., Hanh T. T., Tamura Y.2008. Frequencies of PRNP gene polymorphisms in Vietnamese dairy cattle for potential association with BSE. Zoonoses Public Health 55: 267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Namikawa T., Widodo W.1978. Electrophoretic variation of hemoglobin and serum albumin in the Indonesian cattle including Bali cattle (Bos banteng). Jpn. J. Zootech. Sci. 49: 817–827 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholson E. M., Brunelle B. W., Richt J. A., Kehrli M. E., Jr, Greenlee J. J.2008. Identification of a heritable polymorphism in bovine PRNP associated with genetic transmissible spongiform encephalopathy: evidence of heritable BSE. PLoS ONE 3: e2912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oztabak K., Ozkan E., Soysal I., Paya I., Un C.2009. Detection of prion gene promoter and intron1 indel polymorphisms in Anatolian water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 126: 463–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0388.2009.00821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prusiner S. B.1998. Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95: 13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richt J. A., Hall S. M.2008. BSE associated with prion protein gene mutation. PLoS Pathog. 4: e1000156. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sander P., Hamann H., Drogemuller C., Kashkevich K., Schiebel K., Leeb T.2005. Bovine prion protein gene (PRNP) promoter polymorphisms modulate PRNP expression and may be responsible for differences in bovine spongiform encephalopathy susceptibility. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 37408–37414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506361200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sander P., Hamann H., Pfeiffer I., Wemheuer W., Brenig B., Groschup M. H., Ziegler U., Distl O., Leeb T.2004. Analysis of sequence variability of the bovine prion protein gene (PRNP) in German cattle breeds. Neurogenetics 5: 19–25. doi: 10.1007/s10048-003-0171-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schläpfer I., Saitbekova N., Gaillard C., Dolf G.1999. A new allelic variant in the bovine prion protein gene (PRNP) coding region. Anim. Genet. 30: 386–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.1999.00526-5.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seabury C. M., Honeycutt R. L., Rooney A. P., Halbert N. D., Derr J. N.2004. Prion protein gene (PRNP) variants and evidence for strong purifying selection in functionally important regions of bovine exon 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101: 15142–15147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406403101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimogiri T., Msalya G., Myint S. L., Okamoto S., Kawabe K., Tanaka K., Mannen H., Minezawa M., Namikawa T., Amano T., Yamamoto Y., Maeda Y.2010. Allele distributions and frequencies of the six prion protein gene (PRNP) polymorphisms in Asian native cattle, Japanese breeds, and mythun (Bos frontalis). Biochem. Genet. 48: 829–839. doi: 10.1007/s10528-010-9364-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanton E., Stanton S.2011. 8.5 Dairy cattle breeds. pp. 29–30. In: Vietam Livestock Genetics: A Review of the Market and Opportunities for Canadian Livestock Genetics Exporters, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao H., Wang X. Y., Zou W., Zhang Y. P.2010. Prion protein gene (PRNP) polymorphisms in native Chinese cattle. Genome 53: 138–145. doi: 10.1139/G09-087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]