Abstract

Selective inhibition of function-specific β-GlcNAcase has great potential in terms of drug design and biological research. The symmetrical bis-naphthalimide M-31850 was previously obtained by screening for specificity against human glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcase. Using protein-ligand co-crystallization and molecular docking, we designed an unsymmetrical dyad of naphthalimide and thiadiazole, Q2, that changes naphthalimide specificity from against a human glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcase to against insect and bacterial chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases. The crystallographic and in silico studies reveal that the naphthalimide ring can be utilized to bind different parts of these enzyme homologs, providing a new starting point to design specific inhibitors. Moreover, Q2-induced closure of the substrate binding pocket is the structural basis for its 13-fold increment in inhibitory potency. Q2 is the first non-carbohydrate inhibitor against chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases. This study provides a useful example of structure-based rationally designed inhibitors as potential pharmaceuticals or pesticides.

Glycosyl hydrolase family 20 (GH20) β-N-acetyl-D-glucosaminidases (β-GlcNAcases) (EC 3.2.1.52) catalyze the removal of terminal N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) or N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) residues from various GlcNAc/GalNAc-containing glycans or glycolipids. Crystallographic information has shown that these enzymes employ a substrate-assisted mechanism1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. To handle physiological substrates with different glycosidic linkages (β1,2, β1,3, β1,4 or β1,6) or different architectures (linear or branched, free or conjugated with lipids and proteins), GH20 β-GlcNAcases have evolved to show different substrate preferences5,11,12,13. Hence, selective inhibitors for a certain function-specific enzyme are critical tools for investigating their physiological functions or are of medicinal importance for developing target-specific drugs and agrochemicals14. Inhibitors against human glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcase (HsHex) are potential pharmacological chaperones to cure GM2 gangliosidosis15,16. And inhibitors against fungal, disease-vector insect and agriculture pest chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases are potential agrochemicals17.

Carbohydrate-based small molecules have been reported to inhibit GH20 β-GlcNAcases. Some are very potent with Ki values in the μM to nM range, most of which exhibit almost no selectivity toward function-specific β-GlcNAcases. Representative examples include nagstatin18, PUGNAc19, NAG-thiazoline20, GlcNAcstatinA/B21, pochonicine22,23, DNJNAc24,25 and other iminocyclitols26,27,28,29. The carbohydrate-based TMG-chitotriomycin is the first reported highly-selective inhibitor against chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases from bacteria, fungi and insects, but it is not active toward glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcases from plant and human30,31. Though being successfully synthesized32,33,34, practical application of TMG-chitotriomycin is hard due to its non-drug-like physicochemical properties such as high molecular weight (831.8 Da), low clogP (-6.33) and complex synthetic chemistry.

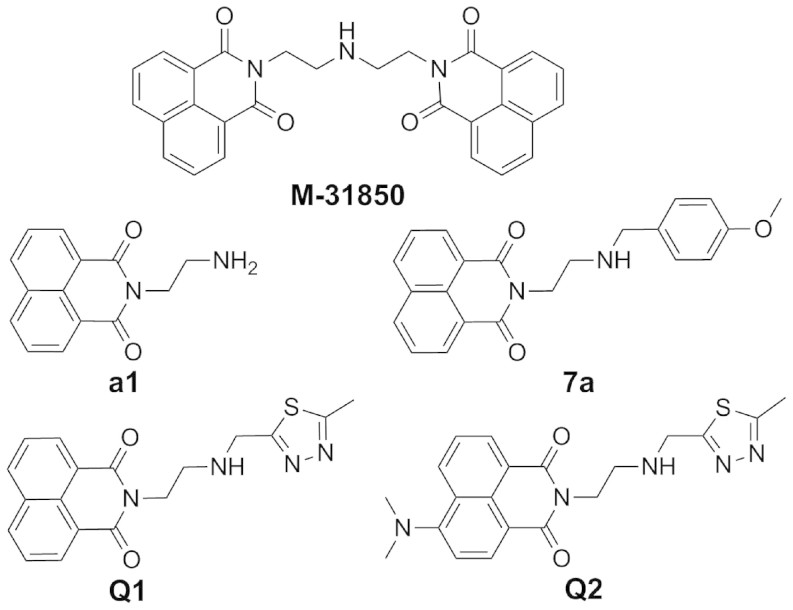

Recent progresses on naphthalimides provide a new starting point to develop specific inhibitors by means of non-carbohydrate-based structures. By screening, M-31850 (Fig. 1), the symmetrical bis-naphthalimide connected by an alkylamine linker, was obtained and found to efficiently inhibit glycoconjugate-lytic HsHex with a Ki value of 0.8 μM. The structure-activity relationship (SAR) of M-31850 and its analogs suggested its binding mode: One naphthalimide binds the active pocket and the other naphthalimide binds to a second hydrophobic patch outside of the active pocket35. Inspired by this work, our group synthesized compounds a136, 7a36 (Fig. 1) and 2037 that selectively inhibit glycoconjugate-lytic HsHex with Ki values of 2.08 μM, 0.63 μM and 1.29 μM, respectively. Compound a1 is a mono-naphthalimide, and M-31850 is a bis-naphthalimide, both exhibit μM-level activities. By replacing one naphthalimide of M-31850 by a methoxyphenyl group, the resulting 7a exhibits an inhibitory activity in the nM range, suggesting an enhanced interaction between the methoxyphenyl group and a hydrophobic patch outside of the active pocket36. However, all naphthalimide-based compounds including M-31850, a1, and 7a do not inhibit the chitinolytic β-GlcNAcase OfHex1 from the important agricultural pest Ostrinia furnacalis13 even at a concentration of 100 μM37.

Figure 1. Structures of naphthalimide-based β-GlcNAcase inhibitors.

Naphthalimide derivatives are easy to synthesize and have served as core scaffolds for many drugs38,39. Naphthalimide-based design thus provides a promising path for developing specific small molecules that target a specific glycan-processing enzyme. Here we describe the design and synthesis of a novel naphthalimide derivative, Q2, which is to our knowledge the first non-carbohydrate inhibitor against insect and bacterial chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases. We further reveal the structural basis for its potency and unique selectivity for chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases over glycoconjugate-lytic ones.

Results and Discussion

Design and bio-evaluation of Q1

In our previous work, structural comparison between HsHex and OfHex1 has revealed that chitinolytic OfHex1 possesses a deep and long substrate-binding pocket with both subsites −1 and +1, whereas glycoconjugate-lytic HsHex possesses a shallow substrate-binding pocket with only subsite -110. Subsites are numbered from −n to +n, where negative sign represents the non-reducing end of the sugar chain40. Thus, the -1 subsite consists of catalytic residues, while the +1 subsite consists of substrate binding residues. Based on crystal structures, the subsite -1 contains two catalytic residues (D367 and E368 in OfHex1, D354 and E355 in HsHex), and the subsite +1 that only OfHex1 have, is comprised by residues V327, E328 and W490.

Because of the selectivity of M-31850, a1, and 7a between HsHex and OfHex1, we hypothesize that the naphthalimide group in M-31850, a1, and 7a can bind to the subsite -1 of a glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcase but not the subsite -1 of a chitinolytic β-GlcNAcase. However, it is worth noting that the subsite +1 of OfHex1 is composed of an aromatic W490 and a hydrophobic V327. Whether this hydrophobic subsite +1 can be utilized to interact with the hydrophobic naphthalimide ring is not reported.

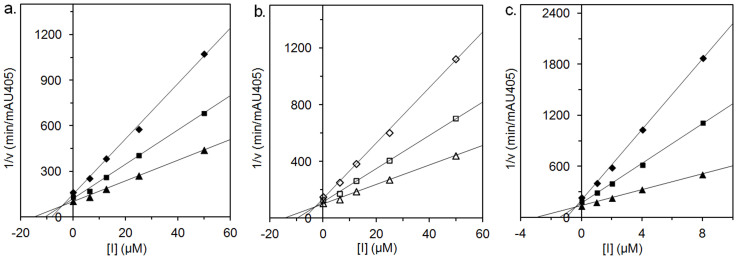

To test this notion, we first designed a novel naphthalimide derivative (Q1) that contains a methylthiadiazole group in place of the methoxyphenyl group in 7a. The methylthiadiazole contains two N atoms and one S atom, which may participate in hydrogen bonds with charged residues (R220, D367, E368, D477 and E526 in OfHex1) at the subsite -1 and facilitate Q1 binding to subsite -1. Using pNP-β-GlcNAc as substrate, Q1 exhibits moderate inhibitory activity toward OfHex1 with a Ki value of 4.28 µM (Table 1). This result suggests that Q1 successfully binds both the subsites -1 and +1 of OfHex1. Q1 also inhibits HsHex with a Ki value of 2.15 µM, which is in the same range as a1 (Ki = 2.08 µM) and M-31850 (Ki = 0.8 µM) for HsHex, suggesting that Q1 binds through its naphthalimide group to HsHex. According to Dixon plots, Q1 acts as a competitive inhibitor toward either OfHex1 or HsHex (Fig. 2a and b).

Table 1. Inhibition constants of Q1 for HsHex and OfHex1.

Figure 2. Dixon plots of inhibition kinetics of Q1 and Q2 against β-GlcNAcases.

(a). Q1 against OfHex1; (b). Q1 against HsHex; (c). Q2 against OfHex1.

Therefore, Q1, a novel naphthalimide-based inhibitor was obtained with equal inhibitory activities for both glycoconjugate-lytic HsHex and chitinolytic OfHex1.

Binding mode of Q1

To test the hypothesis that Q1 inhibits chitinolytic OfHex1 and glycoconjugate-lytic HsHex by different mechanisms, the crystal structure of OfHex1 complexed with Q1 was resolved at a resolution of 2.7 Å. The statistics of data collection and structure refinement were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Details of data collection and structure refinement.

| OfHex1-Q1 | OfHex1-Q2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P 3221 | P 3221 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 107.8, 107.8, 175.3 | 108.0, 108.0, 175.6 |

| α, β, γ (degrees) | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 | 90.0, 90.0, 120.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00-2.70 (2.75-2.70) | 50.00-2.10 (2.14-2.10) |

| Rmerge | 0.132 (0.397) | 0.104 (0.436) |

| I/σI | 15.12 (6.29) | 17.56 (7.43) |

| Completeness (%) | 91.72 (51.54) | 95.56 (65.55) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.70 | 2.10 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.180/0.213 | 0.162/0.181 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein | 4615 | 4626 |

| Ligand/ion | 53 | 56 |

| Water | 158 | 426 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 0.99 | 1.00 |

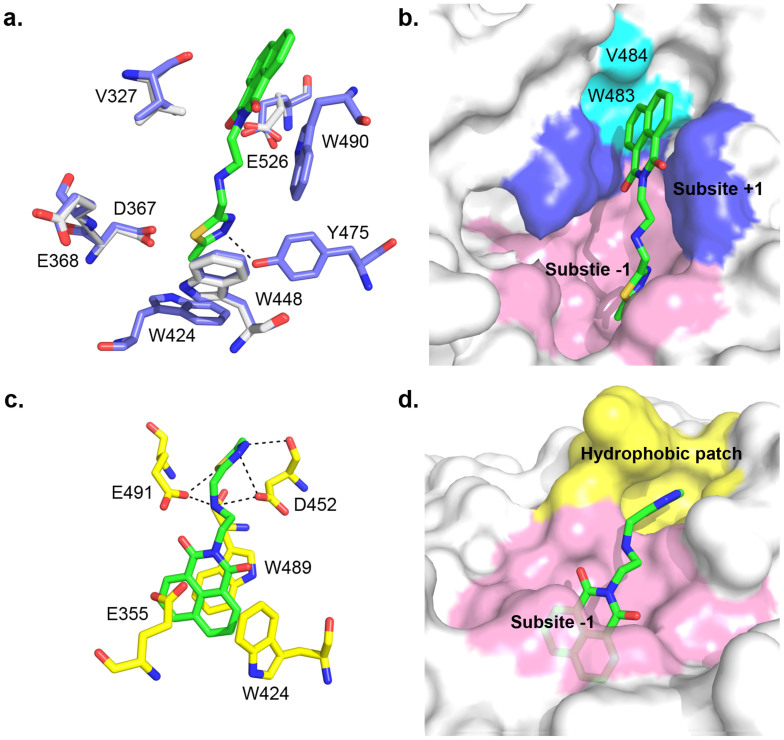

The structural comparison reveals very few conformational changes between unliganded and Q1-complexed OfHex1s (Fig. 3a). The insertion of the naphthalimide group of Q1 at the subsite +1 leads to a 256° rotation of the isopropyl group of V327. The binding of the 2-methylthiadiazole group of Q1 leads to 23° and 53° rotations of D367 and E526, respectively. Q1 binds the entire substrate-binding pocket of OfHex1 in an extended conformation (Fig. 3a and b). The methylthiadiazole group of Q1 is stabilized at the subsite -1 by π-π stacking with the indolyl group of W448. The N3 atom of the 2-methylthiadiazole group forms hydrogen bond with the phenolic hydroxyl group of Y475 within a distance of 2.71 Å. The naphthalimide group of Q1 is sandwiched by the side chains of V327 and W490 at the subsite +1. The π-π stacking interaction between the naphthalimide group of Q1 and the indolyl group of W490 is confirmed by testing the inhibition activity of Q1 against the mutant OfHex1-W490A. As expected, Q1 could not inhibit W490A even at 100 µM, again proving a naphthalimide ring can be utilized by the subsite +1 of OfHex1 (Table 1). Thus, the naphthalimide and 2-methylthiadiazole groups of Q1 interact with OfHex1 at the subsites +1 and −1, respectively.

Figure 3. Crystal structure of Q1-complexed OfHex1 and docked structure of Q1-complexed HsHex.

(a). The superimposition of the unliganded-OfHex1 and Q1-complexed OfHex1. Residues of unliganded-OfHex1 and Q1-complexed OfHex1 are shown in white and blue, respectively. Q1 is shown in green. The hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed black lines. (b). The binding mode of Q1 in the substrate-binding pocket of OfHex1. The subsites −1 and +1 are shown in pink and blue, respectively. W483 and V484 are shown in cyan. (c). and (d). The binding mode of Q1 in the substrate binding-pocket of HsHex. The hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed black lines. The subsites -1 and the hydrophobic patch outside the subsite -1 are shown in pink and yellow, respectively.

To study the binding mode of Q1 in HsHex, Q1 was automatically docked into the substrate-binding pocket of HsHex using AutoDock441. The docking model of Q1 with lowest binding energy was chosen for binding mode analysis (−11.87 kcal mol−1). As expected, the naphthalimide group of Q1 in HsHex is well accommodated by the subsite -1 and sandwiched by W424 and W489 (Fig. 3c and d). The 2-methylthiadiazole group binds a hydrophobic patch outside the subsite -1 comprised by G490-V493, L498, R501 and the main chain of W489 (Fig. 3c and d). Moreover, the secondary nitrogen atom of the linker forms hydrogen bonds with D452 and E491. The sulfur, N2 and N3 atoms of 2-methylthiadiazole group form hydrogen bonds with E491, the side chain and main chain of D452, respectively (Fig. 3c). The docking result showed good agreement with the fact that Q1 has similar inhibitory activity with M-3185035, a136, and 7a36. These results may suggest that a naphthalimide with a bulky substitute might not be able to bind the subsite -1 of the substrate-binding pocket of HsHex.

Therefore, we conclude that a naphthalimide ring can interact with any function-specific β-GlcNAcases but through different mechanisms. Unfortunately, Q1 exhibits very low selectivity between OfHex1 and HsHex (Table 1).

Design and bio-evaluation of Q2, the derivative of Q1

According to the complex structure of OfHex1-Q1, the naphthalimide group of Q1 is positioned in a narrow space beyond the active pocket, which is formed by residues W483 (within a distance of 3.92 Å) and V484 (within a distance of 3.75 Å). The main force for positioning is the π-π stacking interaction one ring of the naphthalimide group with the indolyl group of the W490 at the subsite +1 (Fig. 3a). And the 2-methylthiadiazole group of Q1 forms two intermolecular interactions with the subsite -1, namely a π-π stacking interaction with the indolyl group of the W448 and a hydrogen bond with the phenolic hydroxyl group of the Y475 (Fig. 3a). Moreover, there is no intermolecular interactions observed between Q1 and two catalytic residues (D367 and E368).

Based on the above data, we designed a modified Q1, named Q2, which contains a dimethylamino group at C4 of the naphthalimide. The added group might result in a steric hindrance for Q2 to bind the active pocket of HsHex, eliminating its inhibitory activity toward HsHex. However, although Q2 may not be able to bind the narrow space outside of the active pocket, the modified naphthalimide may rotate to the opposite side and in turn localize the 2-methylthiadiazole group for better interactions with the residues comprising the subsite -1.

Indeed, when pNP-β-GlcNAc is used as a substrate, Q2 exhibits a 13-fold higher activity against OfHex1 with a Ki value of 0.31 µM if compared to Q1 (Table 1). The inhibition is competitive (Fig. 2c). Q2 does not inhibit HsHex even at 100 µM, giving an high selectivity between OfHex1 and HsHex.

The selectivity of Q2 was further tested against several chitinolytic and glycoconjugate-lytic GH20 β-GlcNAcases from different organisms. Q2 does not inhibit any glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcases including OfHex2 from the insect O. furnacalis, CeHex from the plant Canavalia ensformis and BoHex from bovine, but showed clear inhibitory activities against chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases, SmChb from the bacteria Serratia marcescens, SpHex from the bacteria Streptomyces plicatus and TvHex from the fungi Trichoderma viride with Ki values of 8.25, 74.82 and 25.03 µM, respectively.

Thus, a naphthalimide-based non-carbohydrate inhibitor acquires specificity reversal toward two isoforms of GH20 β-GlcNAcases by means of a simple dimethylamination.

Novel binding mode of Q2

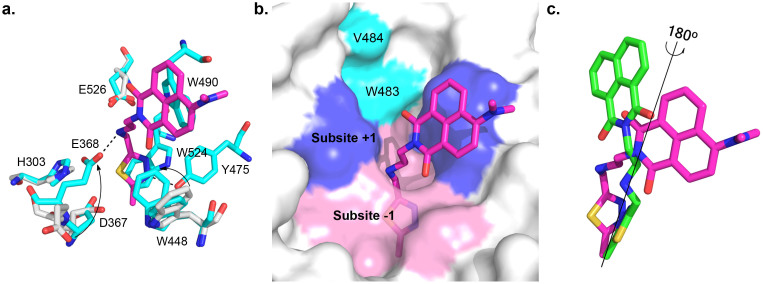

To prove the hypothesized inhibitory mechanism, the crystal structure of OfHex1 complexed with Q2 was resolved to a resolution of 2.1 Å (Table 2). Structure-based comparison between unliganded and Q2-complexed OfHex1 reveals that several residues including H303, D367, E368, W448 and E526 undergo large conformational changes in a manner similar to OfHex1 complexed with TMG-chitotriomycin10 (Fig. 4a). The catalytic E368 rotates approximately 180° and W448 rotates approximately 60°, resulting in tight binding of Q2 to both subsites −1 and +1. Additionally, a dual conformation of W448 was observed, indicating a dynamic balance between the closed and semi-closed state of the active pocket.

Figure 4. Crystal structure of Q2-complexed OfHex1.

(a). The superimposition of the unliganded-OfHex1 and Q2-complexed OfHex1. Residues of unliganded-OfHex1 and Q1-complexed OfHex1 are shown in white and cyan, respectively. The hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed black lines. (b). The binding mode of Q2 in the substrate-binding pocket of OfHex1. The subsites −1 and +1 are shown in pink and blue, respectively. W483 and V484 are shown in cyan. (c). The superimposition of the binding modes of Q1 and Q2 in OfHex1. Q1 and Q2 are shown in green and magenta, respectively.

Q2 occupies the entire substrate binding pocket of OfHex1 but has a different conformation than Q1 (Fig. 4b). Compared with Q1 in OfHex1, the 4-dimethylaminonaphthalimide group of Q2 rotates approximately 180° and engages in π-π stacking with the indolyl group of W490 (Fig. 4c). This conformation change causes the 4-dimethylamino group to leave the restricted space formed by residues W483 and V484 and protrude into the solvent. By virtue of this conformation change, the linker and the methylthiadiazole group of Q2 binds well at the subsite -1 (Fig. 4a and b). The linker of Q2 is bent into a curved conformation and the secondary nitrogen atom forms a 2.81-Å hydrogen bond with the catalytic residue E368. The methylthiadiazole group of Q2 is sandwiched by W524 and W448 and its N3 atom forms a 2.62-Å hydrogen bond with the phenolic hydroxyl group of Y475.

Thus, the structural basis for the 13-fold increment in the inhibitory activity of Q2 for OfHex1 by a simple dimethylamination were revealed to be the different binding mode of naphthalimide ring at subsite +1 and the closure of substrate-binding pocket at subsite -1.

Conclusion

In this paper, by using protein-ligand co-crystallization and molecular docking, we designed and synthesized an unsymmetrical dyad of naphthalimide and thiadiazole, Q2, that switched naphthalimide specificity from against a human glycoconjugate-lytic β-GlcNAcase to against insect and bacterial chitinolytic β-GlcNAcases. Since naphthalimide derivatives are easy to synthesize and have served as core scaffolds for many drugs, this work provides a possibility for developing naphthalimide acting as target-specific pharmaceuticals or pesticides by taking advantage of crystal structure information.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization of β-GlcNAcase inhibitors

The general description of chemical synthesis, the synthesis of intermediates 1, 2 and 3 and the all of the schemes are given as Supplementary files.

2-(2-(((5-methyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)methyl)amino)ethyl)-1H-benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3(2H)-dione (Q1)

Potassium carbonate (383 mg, 2.77 mmol) was added to a solution of 1 (500 mg, 2.08 mmol) and 3 (206 mg, 1.39 mmol) in 20 mL acetonitrile. The mixture was stirred at reflux until the completion of reaction was detected by TLC and then the undissolved substance was removed by filtration. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to give a residue, which was purified by silica gel column chromatography using CH2Cl2/CH3OH (30:1) to give Q1 (250 mg, 51%) as white solid. Rf = 0.43 (CHCl3/MeOH, 30:1); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.59 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 8.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.76 (dd, J = 8.0, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.37 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.22 (s, 2H), 3.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.63 (s, 3H), 1.96 (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 172.0, 165.7, 164.4, 134.1, 131.6, 131.3, 128.2, 127.0, 122.5, 47.9, 47.2, 39.6, 15.6; HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C18H17N4O2S [M+H]+ 353.1072, found 353.1078.

6-(dimethylamino)-2-(2-(((5-methyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)methyl)amino)ethyl)-1H-benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3(2H)-dione (Q2)

The title compound was prepared as yellow oil using 2 and 3 according to the synthetic method of Q1. Yield: 50%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.54 (dd, J = 7.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 8.47–8.40 (m, 2H), 7.64 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.21 (s, 2H), 3.10 (s, 6H), 3.07 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.62 (s, J = 3H), 2.16 (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 172.1, 165.6, 164.8, 164.2, 157.0, 132.7, 131.3, 131.1, 130.3, 125.2, 124.8, 122.9, 114.7, 113.2, 47.8, 47.3, 44.7, 39.4, 15.5; HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C20H22N5O2S [M+H]+ 396.1494, found 396.1494.

Enzyme preparation

OfHex1 and OfHex2 from O. furnacalis were expressed and purified as described in our previous works42. The SmChb from S. marcescens was recombinantly expressed and purified according to the reported methods43. SpHex from S. plicatus was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beijing, China). Human HsHex, bovine BtHex, plant CeHex from C. ensformis and fungal TvHex from T. viride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China).

Enzyme Activity Assay

The enzymatic activities of Hexes and chitinases measured at 25°C using 4-nitrophenyl-N-acetyl-β-acetylglucosamine (pNP-β-GlcNAc, Sigma-Aldrich). OfHex1, SmChb and TvHex were assayed in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and HsHex, CeHex and SpHex were assayed in 20 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5). After incubating for appropriate time, 0.5 M Na2CO3 was added to the reaction mixture and the absorbance at 405 nm was monitored using a Sunrise microplate reader (TECAN, Shanghai, China). As for Ki value determination, three substrate concentrations (0.075, 0.125 and 0.2 mM) were used. The concentrations of inhibitor varied for different enzyme. The Ki values and types of inhibition were determined by linear fitting of data in Dixon plots.

Protein Crystallization and Structure Determination

Crystallization experiments were performed by the hanging drop-vapor diffusion method at 4°C. OfHex1 was desalted in 20 mM bis-Tris with 50 mM NaCl (pH 6.5) and concentrated to 7.0 mg mL−1 by ultracentrifugation. The crystal of Q1 and Q2-complexed OfHex1were obtained within 2 weeks with 10-fold excess of Q1 and Q2 in mother liquid A (100 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 100 mM MgCl2, 30% PEG400) and mother liquid B (100 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 mM MgCl2, 35% PEG400), respectively. Diffraction data was collected at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, BL-17U (ADSC Quantum 315r CCD at 100 K), and processed using HKL200044.

The structures of Q1 and Q2-complexed OfHex1 were solved by molecular replacement with PHASER45 using the structure of the unliganded OfHex1 (PDB code: 3NSM) as the model. PHENIX46 was used for structure refinement. The molecular models were manually built and extended using Coot47. The stereochemistry of the models was checked by PROCHECK48. Coordinates for OfHex1-Q1 and OfHex1-Q2 complexes have been deposited with accession codes 3MWB and 3MWC. All structural figures were generated using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA, USA).

Molecular Docking

The PDB files of the Q1 were generated by PRODRG49. The ligand-free PDB file of HsHex (PDB code 1NP0) were prepared by PyMOL. The PDBQT files of the proteins and compounds were prepared by MGLTools41. Affinity grid of 70 × 70 × 70 Å positioned on the center of the ligand (NAG-thiazoline in HsHex) was calculated using AutoGrid441. Molecular dockings were done by AutoDock441 using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm with a population size of 150 individuals, 25,000,000 energy evaluations and 27,000 generations. Plausible docking models were selected from the most abundant cluster (RMSD = 2 Å) which had lowest binding energy.

Author Contributions

T.L., Q.Y. and X.Q. conceived and designed the project. P.G. and H.Y. performed inhibitor synthesis and chemical characterization. T.L. and J.W. performed protein expression, purification, crystallization and inhibitor biochemical characterization. Y.Z. and L.C. performed the X-ray crystallography experiments and data analysis. T.L., Q.Y. and X.Q. analyzed the results. Q.Y., T.L. and P.G. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental methods

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Project for Basic Research (2010CB126100), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2011AA10A204), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31101671, 61202252), the Program for Liaoning Excellent Talents in University (LJQ2014006), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DUT14LK13) and the Open Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol at Sun Yat-Sen University (SKLBC13KF01).

References

- Tews I. et al. Bacterial chitobiase structure provides insight into catalytic mechanism and the basis of Tay-Sachs disease. Nat Struct Biol 3, 638–648 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark B. L. et al. Crystallographic evidence for substrate-assisted catalysis in a bacterial β-hexosaminidase. J Biol Chem 276, 10330–10337 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark B. L. et al. Crystal structure of human β-hexosaminidase B: Understanding the molecular basis of Sandhoff and Tay-Sachs disease. J Mol Biol 327, 1093–1109 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T. et al. The X-ray crystal structure of human β-hexosaminidase B provides new insights into Sandhoff disease. J Mol Biol 328, 669–681 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubbu N., Thomas L. M., Ragunath C. & Kaplan J. B. Structural analysis of dispersin B, a biofilm-releasing glycoside hydrolase from the periodontopathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Mol Biol 349, 475–486 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux M. J. et al. Crystallographic structure of human β-hexosaminidase A: interpretation of Tay-Sachs mutations and loss of GM2 ganglioside hydrolysis. J Mol Biol 359, 913–929 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley D. B. et al. Structure of N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (GcnA) from the endocarditis pathogen Streptococcus gordonii and its complex with the mechanism-based inhibitor NAG-thiazoline. J Mol Biol 377, 104–116 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida T., Ishii R., Yanagisawa T., Yokoyama S. & Ito M. Molecular cloning and crystal structural analysis of a novel β-N-acetylhexosaminidase from Paenibacillus sp. TS12 capable of degrading glycosphingolipids. J Mol Biol 392, 87–99 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. et al. Structural basis for the substrate specificity of a novel β-N-acetylhexosaminidase StrH protein from Streptococcus pneumoniae R6. J Biol Chem 286, 43004–43012 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. et al. Structural determinants of an insect β-N-Acetyl-D-hexosaminidase specialized as a chitinolytic enzyme. J Biol Chem 286, 4049–4058 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluvinage B. et al. Inhibition of the pneumococcal virulence factor StrH and molecular insights into N-glycan recognition and hydrolysis. Structure 19, 1603–1614 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard R. et al. The Drosophila fused lobes gene encodes an N-acetylglucosaminidase involved in N-glycan processing. J Biol Chem 281, 4867–4875 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Liu T., Liu F., Qu M. & Qian X. A novel β-N-acetyl-D-hexosaminidase from the insect Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenée). FEBS J 275, 5690–5702 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster T. M. & Vocadlo D. J. Developing inhibitors of glycan processing enzymes as tools for enabling glycobiology. Nat Chem Biol 8, 683–694 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropak M. B. & Mahuran D. Lending a helping hand, screening chemical libraries for compounds that enhance β-hexosaminidase A activity in GM2 gangliosidosis cells. FEBS J 274, 4951–4961 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R. E. et al. Pharmacological chaperones as therapeutics for lysosomal storage diseases. J Med Chem 56, 2705–2725 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X., Lee P. W. & Cao S. China: forward to the green pesticides via a basic research program. J Agric Food Chem 58, 2613–2623 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama T. et al. The structure of nagstatin, a new inhibitor of N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 45, 1557–1558 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch M., Hoesch L., Vasella A. & Rast D. M. N-acetylglucosaminono-1,5-lactone oxime and the corresponding (phenylcarbamoyl)oxime. Novel and potent inhibitors of β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. Eur J Biochem 197, 815–818 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S. et al. NAG-thiazoline, an N-acetyl-β-hexosaminidase inhibitor that implicates acetamido participation. J Am Chem Soc 118, 6804–6805 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Dorfmueller H. C. et al. GlcNAcstatin: a picomolar, selective O-GlcNAcase inhibitor that modulates intracellular O-GlcNAcylation levels. J Am Chem Soc 128, 16484–16485 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuki H., Toyo-oka M., Kanzaki H., Okuda T. & Nitoda T. Pochonicine, a polyhydroxylated pyrrolizidine alkaloid from fungus Pochonia suchlasporia var. suchlasporia TAMA 87 as a potent β-N-acetylglucosaminidase inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem 17, 7248–7253 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. et al. Synthesis of eight stereoisomers of pochonicine: nanomolar inhibition of β-N-acetylhexosaminidases. J Org Chem 78, 10298–10309 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P. et al. Novel five-membered iminocyclitol derivatives as selective and potent glycosidase inhibitors: New structures for antivirals and osteoarthritis. Chembiochem 7, 165–173 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glawar A. F. G. et al. Scalable syntheses of both enantiomers of DNJNAc and DGJNAc from glucuronolactone: The effect of N-alkylation on hexosaminidase inhibition. Chem-Eur J 18, 9341–9359 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree J. S. S. et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of enantiomeric β-N-acetylhexosaminidase inhibitors LABNAc and DABNAc as potential agents against Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff disease. Chemmedchem 4, 378–392 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. et al. Development of GlcNAc-inspired iminocyclitiols as potent and selective N-acetyl-β-hexosaminidase inhibitors. ACS Chem Biol 5, 489–497 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers B. J. et al. Nine of 16 stereoisomeric polyhydroxylated proline amides are potent beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase inhibitors. J Org Chem 79, 3398–3409 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree E. V. et al. Synthesis of the enantiomers of XYLNAc and LYXNAc: comparison of beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase inhibition by the 8 stereoisomers of 2-N-acetylamino-1,2,4-trideoxy-1,4-iminopentitols. Org Biomol Chem 12, 3932–3943 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuki H. et al. TMG-chitotriomycin, an enzyme inhibitor specific for insect and fungal β-N-acetylglucosaminidases, produced by actinomycete Streptomyces anulatus NBRC 13369. J Am Chem Soc 130, 4146–4152 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiota H., Kanzaki H., Hatanaka T. & Nitoda T. TMG-chitotriomycin as a probe for the prediction of substrate specificity of β-N-acetylhexosaminidases. Carbohyd Res 375, 29–34 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Li Y. & Yu B. Total synthesis and structural revision of TMG-chitotriomycin, a specific inhibitor of insect and fungal β-N-acetylglucosaminidases. J Am Chem Soc 131, 12076–12077 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. et al. Synthesis, evaluation, and mechanism of N,N,N-trimethyl-D-glucosamine-1,4-chitooligosaccharides as selective inhibitors of glycosyl hydrolase family 20 β-N-acetyl-D-hexosaminidases. Chembiochem 12, 457–467 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halila S., Samain E., Vorgias C. E. & Armand S. A straightforward access to TMG-chitooligomycins and their evaluation as β-N-acetylhexosaminidase inhibitors. Carbohyd Res 368, 52–56 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropak M. B., Blanchard J. E., Withers S. G., Brown E. D. & Mahuran D. High-throughput screening for human lysosomal β-N-acetyl hexosaminidase inhibitors acting as pharmacological chaperones. Chem Biol 14, 153–164 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P. et al. Development of unsymmetrical dyads as potent noncarbohydrate-based inhibitors against human β-N-acetyl-D-hexosaminidase. ACS Med Chem Lett 4, 527–531 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. et al. Exploring unsymmetrical dyads as efficient inhibitors against the insect β-N-acetyl-D-hexosaminidase OfHex2. Biochimie 97, 152–162 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S. et al. Recent advances in the development of 1,8-naphthalimide based DNA targeting binders, anticancer and fluorescent cellular imaging agents. Chem Soc Rev 42, 1601–1618 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A., Bolla N. R., Srikanth P. S. & Srivastava A. K. Naphthalimide derivatives with therapeutic characteristics: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat 23, 299–317 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G., Wilson K. & Henrissat B. Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J 321, 557–559 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 30, 2785–2791 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Liu F., Yang Q. & Yang J. Expression, purification and characterization of the chitinolytic β-N-acetyl-D-hexosaminidase from the insect Ostrinia furnacalis. Protein Expres Purif 68, 99–103 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tews I., Vincentelli R. & Vorgias C. E. N-acetylglucosaminidase (chitobiase) from Serratia marcescens: gene sequence, and protein production and purification in Escherichia coli. Gene 170, 63–67 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. & Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol 276, 307–326 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A. J. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 63, 32–41 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G. & Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A., Macarthur M. W., Moss D. S. & Thornton J. M. Procheck-a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr 26, 283–291 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Schuttelkopf A. W. & van Aalten D. M. F. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 1355–1363 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental methods