Abstract

Inflammatory monocytes play an important role in host defense against infections. However, the regulatory mechanisms of transmigration into infected tissue are not yet completely understood. Here we show that mice deficient in MAIR-II (also called CLM-4 or LMIR2) are more susceptible to caecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced peritonitis than wild-type (WT) mice. Adoptive transfer of inflammatory monocytes from WT mice, but not from MAIR-II, TLR4 or MyD88-deficient mice, significantly improves survival of MAIR-II-deficient mice after CLP. Migration of inflammatory monocytes into the peritoneal cavity after CLP, which is dependent on VLA-4, is impaired in above mutant and FcRγ chain-deficient mice. Lipopolysaccharide stimulation induces association of MAIR-II with FcRγ chain and Syk, leading to enhancement of VLA-4-mediated adhesion to VCAM-1. These results indicate that activation of MAIR-II/FcRγ chain by TLR4/MyD88-mediated signalling is essential for the transmigration of inflammatory monocytes from the blood to sites of infection mediated by VLA-4.

Inflammatory monocytes play an important role in host defense against infections. Here the authors provide insights into the mechanism behind the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to sites of infection by demonstrating the involvement of Toll-like receptor 4 and MAIR-II immunoreceptors in this process.

Inflammatory monocytes play an important role in host defense against infections. Here the authors provide insights into the mechanism behind the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to sites of infection by demonstrating the involvement of Toll-like receptor 4 and MAIR-II immunoreceptors in this process.

Monocytes are able to differentiate into macrophages or dendritic cells to induce innate and adaptive immunities1. There are two subsets of murine monocytes: CX3CR1int CCR2+ Ly6Chigh inflammatory monocytes (iMo), and CX3CR1high CCR2− Ly6Clow patrolling monocytes2,3. Monocyte recruitment is a crucial part of the host defense against invading microorganisms4. iMo are rapidly recruited to sites of infection and inflammation, where they protect the host from infection by bacteria, parasites or viruses5,6,7; however, they are also involved in the exacerbation of the pathogeneses of myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis and cancer8,9,10. iMo play an important role in protection from caecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced peritonitis, which is widely regarded as the most representative animal model of human polymicrobial sepsis11. iMo egress from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood via CC-chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2)-dependent mechanisms6,12. However, the recruitment of iMo from the blood to sites of infection is CCR2-independent; instead, it requires adhesion molecules such as very late antigen-4 (VLA-4)13,14. Conformational changes in individual integrin heterodimers leads to an increase in ligand-binding energy and a marked decrease in the rate of ligand dissociation15. Despite this knowledge, exactly how iMo transmigrate to sites of infection is not yet completely understood.

Myeloid-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor (MAIR)-II16,17,18(also called LMIR2 (ref. 19) or CLM-4 (ref. 20)), which is encoded by AF251705, is a member of the CD300 family of cell surface molecules that is encoded by nine genes on the small segment of mouse chromosome 11 (refs 20, 21). The human CD300 family comprises seven members, which are encoded by genes located on chromosome 17 in a region syntenic to mouse chromosome 11 (ref. 22). MAIR-II is expressed on macrophages and a subset of B cells in the spleen and the peritoneal cavity16,17. MAIR-II non-covalently associates with the signalling adaptor DAP12, which bears the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif (ITAM), in macrophages and B cells16,18. MAIR-II mediates an activating signal for the production of the proinflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 in macrophages16,17. Interestingly, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) enhances FcεRIγ (FcRγ chain) expression and induces the association of MAIR-II with FcRγ chain in peritoneal macrophages, but not in splenic macrophages or B cells, for which the lysine residue in the transmembrane region of MAIR-II is responsible17. In contrast, MAIR-II negatively regulates adaptive immune responses by B cells in a DAP12-dependent manner18. The physiological role of MAIR-II is not yet completely understood.

Here we show that MAIR-II is expressed on iMo and is involved in Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4)-mediated iMo transmigration from the blood to sites of infection as part of the host response to polymicrobial peritonitis.

Results

AF251705 −/− mice are susceptible to peritonitis

To address the role of MAIR-II in myeloid cell function in vivo, we first investigated whether MAIR-II deficiency affected the pathophysiology of peritonitis in the CLP model. Wild-type (WT) mice that underwent CLP exhibited <10% mortality at 7 days after CLP, whereas the AF251705−/− mice showed markedly shorter survival than WT mice (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Severe multiorgan injury was observed in AF251705−/− mice but not in WT mice (Fig. 1b). The number of peritoneal aerobic bacteria was increased in AF251705−/− mice compared with WT mice at 20 h after CLP (Fig. 1c). Moreover, serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were significantly increased in AF251705−/− mice compared with WT mice after CLP (Fig. 1d). These results indicate that AF251705−/− mice are more susceptible to CLP-induced peritonitis than WT mice.

Figure 1. AF251705−/− mice are more susceptible to CLP-induced peritonitis than WT mice.

(a) WT and AF251705−/− mice (n=15 per group) were subjected to CLP. Mice were monitored every 6 h for 7 days to determine survival. (b) Representative features of the peritoneal cavity of WT or AF251705−/− mice 20 h after CLP. (c) Bacterial numbers in the peritoneal cavity of WT or AF251705−/− mice (n=10 per group) 20 h after CLP. (d) Plasma levels of TNF-α and IL-6 20 h after CLP in WT or AF251705−/− mice (n=10 per group). CFU, colony forming unit. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (log-rank test in a, Mann–Whitney U-analyses in c and two-tailed Student’s t-test in d). Data are representative of three (a) or two (b–d) independent experiments. Error bars indicate s.d. (c,d).

MAIR-II regulates the migration of M&phage/Mo after CLP

As acute septic peritonitis promotes the recruitment of macrophages/monocytes (Mφ/Mo) and neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity23,24, we next assessed the influx of Mφ/Mo and neutrophils in the peritoneal cavities of WT and AF251705−/− mice after CLP. Before CLP, WT mice and AF251705−/− mice did not show any difference in myeloid cell populations in the peripheral blood and bone marrow (Supplementary Table 1). Total cell number, the number of neutrophils (CD11b+ F4/80− Ly6Ghigh) and apoptotic cells (PI+) in the peritoneal cavities were increased in both WT mice and AF251705−/− mice 8 and 20 h after CLP. However, the number of Mφ/Mo (CD11b+ F4/80+) was significantly increased only in WT mice (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 2. MAIR-II regulates the influx of iMo to the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

(a,b) Numbers of total cells, Mφ/Mo (CD11b+ F4/80+), neutrophils (CD11b+ F4/80− Ly6G+) and apoptotic cells (PI+) in the peritoneal cavity of WT or AF251705−/− mice, 8 (n=5) or 20 h (n=15) after CLP operation. (c) Liposome-encapsulated PBS- or liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene bisphosphate (Cl2MBP)-treated WT and AF251705−/− mice were subjected to CLP. Mice were monitored every 6 h for 6 days to determine survival (n=9–11 per group). (d) Flow cytometry analysis of MAIR-II expression on iMo (Ly6G− F4/80high Ly6Chigh), patrolling monocytes (pMo) (Ly6G− F4/80low Ly6Clow) and neutrophils (Ly6Ghigh F4/80low) in the bone marrow. (e,f) iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were intravenously transferred into AF251705−/− mice after CLP and monitored every 6 h for 6 days to determine survival (n=10 per group). Mock indicates mice that received PBS alone after CLP (e). Bacterial titres in the peritoneal cavity 20 h after CLP were determined by colony-forming unit (CFU) assay (f). (g) CFSE-labelled iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were intravenously transferred into AF251705−/− mice 20 h after CLP. Numbers of migrated CFSE+ iMo in the peritoneal cavity were analysed by using flow cytometry 20 h after CLP (n=10 per group). (h) The mixture of equal number of CFSE-labelled WT (CD45.1+) and AF251705−/− (CD45.2+) iMo were intravenously transferred into AF251705−/− mice immediately before CLP. The proportions of transferred CD45.1+ (WT) and CD45.1− (AF251705−/−) iMo in the peritoneal cavity were analysed by using flow cytometry 20 h after CLP (n=4 per group). N.S., not significant. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test in (a,b,g,h), log-rank test in (c,e) and Mann–Whitney U-analyses in f). Error bars indicate s.d. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

To examine the importance of the influx of Mφ/Mo into the peritoneal cavity in the survival after CLP, we used liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene bisphosphonate (Cl2MBP-liposomes) to deplete Mφ/Mo in the CLP model. We administered liposome-encapsulated PBS-liposomes or Cl2MBP-liposomes to WT or AF251705−/− mice 1 day before CLP. At 20 h after CLP, Cl2MBP-liposomes had selectively depleted Mφ/Mo, but not neutrophils, in the peritoneal cavity of both WT and AF251705−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although PBS-liposome-treated WT mice showed significantly longer survival than PBS-liposome-treated AF251705−/− mice, Cl2MBP-liposome-treated WT mice showed increased mortality at the same level as Cl2MBP-liposome-treated AF251705−/− mice (Fig. 2c). Taken together, these results suggest that MAIR-II regulates the influx of Mφ/Mo into the peritoneal cavity, which contributes to the longer survival of WT mice after CLP.

WT iMo protects AF251705 −/− mice from peritonitis

iMo are rapidly recruited to sites of infection and inflammation, and they play a critical protective role in the CLP model5,6,7,11. As we found that MAIR-II is highly expressed on iMo (Ly6G−F4/80high Ly6Chigh), but not on both patrolling monocytes (Ly6G−F4/80low Ly6Clow) and neutrophils (Ly6Ghigh F4/80low) (Fig. 2d), we investigated whether MAIR-II expressed on iMo is involved in protecting mice from CLP-induced peritonitis. AF251705−/− mice were injected with iMo purified from either WT or AF251705−/− mice, and the mice then underwent CLP. We found that AF251705−/− mice that received WT iMo showed significantly improved survival after CLP compared with mice that received AF251705−/− iMo (Fig. 2e). Moreover, although phagocytosis of Escherichia coli was comparable in WT and AF251705−/− iMo (Supplementary Fig. 3), the numbers of peritoneal aerobic bacteria were reduced in mice that received WT iMo compared with mice that received AF251705−/− iMo (Fig. 2f). These results indicate that MAIR-II expressed on iMo plays an important role in protecting against septic peritonitis, suggesting that MAIR-II is involved in the migration of iMo into the peritoneal cavity.

To test this hypothesis, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labelled iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were adoptively transferred to AF251705−/− mice immediately before CLP. Significantly more CFSE-labelled iMo were detected in the peritoneal cavity of mice that received CFSE-labelled WT iMo than in mice that received CFSE-labelled AF251705−/− iMo at 20 h after CLP (Fig. 2g), suggesting that AF251705−/− iMo were impaired in migration into the peritoneal cavity compared with WT iMo. To examine whether this is derived from an intrinsic defect of AF251705−/− iMo function, 1:1 mixture of CFSE-labelled WT (CD45.1+) and AF251705−/− (CD45.2+) iMo were adoptively transferred to AF251705−/− mice immediately before CLP. We observed again that significantly more WT (CD45.1+) iMo were detected in the peritoneal cavity than AF251705−/− (CD45.1−) iMo at 20 h after CLP (Fig. 2h). These results indicate that MAIR-II plays an important role in the migration of iMo to sites of inflammation in the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

VLA-4 is involved in iMo migration

Although CCR2 expressed on iMo and its ligand CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) play an important role in the egress of iMo from the bone marrow to the peripheral blood12, several lines of evidence demonstrate that the interaction between CCR2 and CCL2 is not involved in the migration of iMo from the peripheral blood to sites of infection4. Indeed, the concentration of CCL2 in lavage fluid taken from the peritoneal cavity after CLP and the expression of CCR2 on iMo were comparable in WT and AF251705−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). Further studies did not show any difference in the levels of other chemokines and cytokines in the lavage fluid after CLP (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

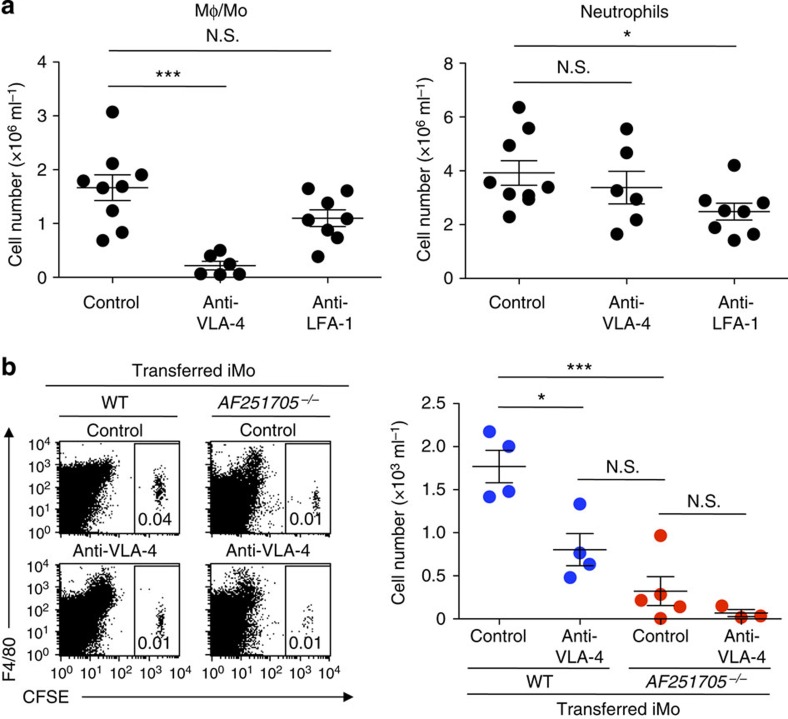

Previous reports demonstrated that the recruitment of iMo from the blood to sites of infection requires adhesion molecules such as VLA-4 (refs 13, 14). To examine whether VLA-4 is also involved in the recruitment of iMo into the peritoneal cavity after CLP, mice were injected with either a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against VLA-4 or LFA-1 immediately before CLP. The number of Mφ/Mo in the peritoneal cavity after CLP in mice that were injected with anti-VLA-4 mAb was significantly lower than in mice that received control antibody. However, the neutrophil number after CLP was comparable between these two groups (Fig. 3a). By contrast, mice that were treated with anti-LFA-1 mAb showed significantly lower number of neutrophils, but not Mφ/Mo, in the peritoneal cavity after CLP compared with mice that were treated with control antibody (Fig. 3a). These results suggest that VLA-4 and LFA-1 play an important role in transmigration of iMo and neutrophils, respectively, into the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

Figure 3. VLA-4 plays a critical role in transmigration of iMo into the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

(a) Mice were treated with control antibody, anti-VLA-4 mAb or anti-LFA-1 mAb immediately before CLP. Numbers of Mφ/Mo (CD11b+ F4/80+) and neutrophils (CD11b+ F4/80− Ly6G+) in the peritoneal cavity 20 h after CLP operation (n=6–9 per group). (b) CFSE-labelled iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were adoptively transferred intravenously into AF251705−/− mice. These mice were treated with anti-VLA-4 mAb or control antibody immediately before CLP. Migrated CFSE+ iMo in the peritoneal cavity were counted by using flow cytometry 20 h after CLP (n=4 or 5 per group). N.S., not significant. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test in a,b). Error bars indicate s.d. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

To directly demonstrate the involvement of VLA-4 in migration of iMo to the peritoneal cavity after CLP, CFSE-labelled iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were adoptively transferred to AF251705−/− mice. These mice were treated with either anti-VLA-4 mAb or control antibody immediately before CLP. Significantly more CFSE-labelled WT iMo were detected in the peritoneal cavity of mice that were treated with control antibody compared with in mice that were treated with anti-VLA-4 mAb (Fig. 3b). However, treatment with anti-VLA-4 mAb did not affect the number of CFSE-labelled AF251705−/− iMo (Fig. 3b). Taken together, these results indicate that VLA-4 as well as MAIR-II plays a critical role in transmigration of iMo into the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

TLR4 and MyD88 are involved in iMo migration

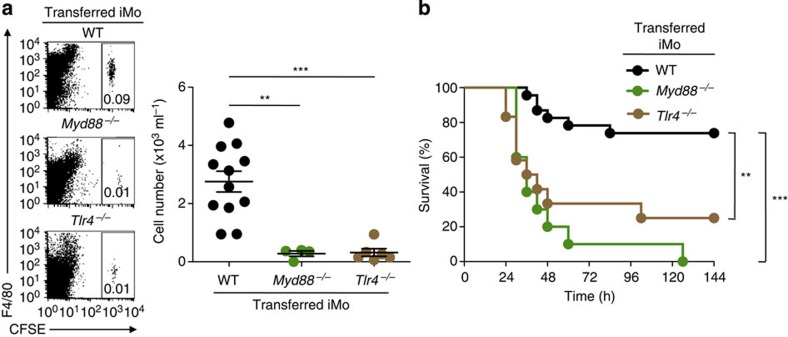

We previously reported that simultaneous stimulation of peritoneal macrophages with an anti-MAIR-II mAb and LPS synergistically increased the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α17, suggesting that MAIR-II functionally associates with TLR4. Recent evidence also suggests that MyD88 and TLR4 are required for protection from CLP-induced peritonitis25,26. To examine whether iMo require the interaction of MAIR-II with TLR4 signalling for their recruitment after CLP, we adoptively transferred CFSE-labelled iMo from WT, Myd88−/− or Tlr4−/− mice into AF251705−/− mice, as well as WT mice. Recruitment of iMo from Myd88−/− and Tlr4−/− mice into the peritoneal cavity of both AF251705−/− and WT mice was impaired compared with the recruitment of iMo from WT mice (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, the adoptive transfer of iMo from WT, but not Myd88−/− and Tlr4−/−, mice improved survival in AF251705−/− mice after CLP (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that TLR4/MyD88 signalling is critical for the recruitment of iMo into the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

Figure 4. iMo require TLR4 and MyD88 signalling for their recruitment.

(a,b) CFSE-labelled (a) or unlabelled (b) iMo from WT, Myd88−/− or Tlr4−/− mice were transferred intravenously into AF251705−/− mice immediately before CLP. Numbers of migrated CFSE+ iMo in the peritoneal cavity were counted 20 h after CLP (n=4, 6 or 12 per group) (a). Mice were monitored every 6 h for 6 days to determine survival (n=10 per group) (b). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test in a and log-rank test in b). Error bars indicate s.d. (a). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

LPS induces association of MAIR-II with TLR4 and FcRγ chain

We next examined whether MAIR-II is physically and functionally associated with TLR4 by using RAW264.7 macrophage transfectants stably expressing Flag-tagged MAIR-II or Flag-tagged CD300a, which is highly homologous to MAIR-II in the extracellular domain16. Although both MAIR-II and CD300a were not coimmunoprecipitated with TLR4 in the steady state, MAIR-II, but not CD300a, was coimmunoprecipitated with TLR4 after LPS stimulation (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs 6a and 7). As both RAW264.7 transfectants expressing Flag-tagged CD300a and MAIR-II expressed comparable amount of Flag protein (Supplementary Fig. 8), these results indicated that MAIR-II, but not CD300a, specifically associates with TLR4 after stimulation with LPS. To investigate whether FcRγ chain is involved in this association, we further analysed the association of TLR4 with FcRγ-interacting mouse CD300 molecules MAIR-IV/CLM-5/LMIR4 and CD300f27. We found that MAIR-IV/CLM-5/LMIR4, but not CD300f, was coimmunoprecipitated with TLR4 after stimulation with LPS (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that LPS stimulation indeed induces physical association of TLR4 with certain FcRγ-interacting CD300 molecules such as MAIR-II/CLM-4 and MAIR-IV/CLM-5.

Figure 5. LPS enhances the association of MAIR-II with TLR4 and FcRγ chain, and amplifies Syk activation via FcRγ chain.

(a,b,d,e,f) RAW264.7, its transfectants expressing Flag-tagged CD300a or Flag-tagged MAIR-II (a,b,d,e) and iMo (f) were left unstimulated or stimulated with LPS for 20 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against TLR4 (a), Flag (b,d), DAP12 (e) or FcRγ chain (f), and immunoblotted with the antibodies indicated. (c) iMo were left unstimulated or stimulated with LPS for 20 h and analysed for Fcer1g and Tyrobp expression by using real-time reversre transcription–PCR. ***P<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). Error bars indicate s.d. (c). Data are representative of three (a) or two (b–e) independent experiments.

We previously demonstrated that MAIR-II associates with DAP12 and FcRγ chain in peritoneal macrophages17. To clarify the signalling pathway from the TLR4/MAIR-II complex, we next assessed the association of MAIR-II with DAP12 or FcRγ chain after LPS stimulation. We observed that MAIR-II was coimmunoprecipitated with both DAP12 and FcRγ chain in the steady state (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 6b). LPS stimulation increased the association of MAIR-II with FcRγ chain, but decreased the association with DAP12, in RAW264.7 transfectant expressing Flag-tagged MAIR-II (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 6b). In line with these results, we found that stimulation of iMo with LPS upregulated the expression of FcRγ chain-encoding Fcer1g mRNA but downregulated the expression of DAP12-encoding Tyrobp mRNA (Fig. 5c). Moreover, stimulation of the RAW264.7 transfectants with LPS significantly induced tyrosine phosphorylation of MAIR-II-coupled FcRγ chain (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 6c).

The phosphorylation of the ITAM tyrosine residues of FcRγ chain leads to the recruitment of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) through its tandem SH2 domains28. In fact, we observed that FcRγ chain was coimmunoprecipitated with Syk, which was tyrosine-phosphorylated after LPS stimulation (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 6c). In contrast, we did not observe the tyrosine phosphorylation of DAP12-coupled Syk (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 6d). To demonstrate the tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain associated with MAIR-II also in primary iMo, we stimulated iMo purified from the bone marrow cells of WT or AF251705−/− mice with LPS. LPS stimulation increased tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain in WT iMo compared with that in AF251705−/− iMo (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 6e), suggesting that LPS also induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of MAIR-II-coupled FcRγ chain in primary iMo. Taken together, these results indicate that LPS stimulation upregulated FcRγ chain expression but downregulated DAP12 expression, which might result in the physical and functional association of MAIR-II with FcRγ chain and subsequent activation of Syk.

iMo require FcRγ for migration into the peritoneal cavity

As recent studies have demonstrated that DAP12 and FcRγ chain, and a downstream signalling protein, Syk, promote the activation of integrin adhesion molecules such as VLA-4 (refs 29, 30, 31), WT or AF251705−/− iMo were incubated on culture dishes precoated with the VLA-4 ligand VCAM-1 fused with the Fc portion of human IgG1 (VCAM-1-Fc) in the presence or absence of LPS. LPS stimulation of WT iMo increased cellular adhesion to the VCAM-1-Fc-coated but not human IgG1-coated culture dishes, suggesting that the LPS-induced adhesion of iMo is mediated by VCAM-1-Fc. In contrast, iMo from AF251705−/− mice did not adhere to VCAM-1-Fc in response to LPS (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 9a). We observed the similar results in the flow adhesion assays, as described previously32 (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Movies 1–4). As WT and AF251705−/− iMo expressed comparable amount of VLA-4 (Supplementary Fig. 9b), these results suggest that the affinity of VLA-4 of WT iMo was higher than that of AF251705−/− iMo. Similarly, LPS stimulation did not enhance the adhesion of Fcer1g−/− iMo to VCAM-1-Fc (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 9c). In contrast, Tyrobp−/− iMo showed enhanced adhesion after LPS stimulation (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 9c). Moreover, iMo from Fcer1g−/− or AF251705−/− mice showed impaired migration into the peritoneal cavity compared with those from WT mice (Fig. 6d). In contrast, migration of Tyrobp−/− iMo into the peritoneal cavity was comparable with WT iMo (Fig. 6d). In agreement with these results, the adoptive transfer of iMo from WT and Tyrobp−/−, but not AF251705−/− and Fcer1g−/−, mice improved survival of AF251705−/− mice after CLP (Fig. 6e). Together, these results indicate that FcRγ chain, but not DAP12, plays an important role in the TLR4/MAIR-II-mediated adhesion of iMo to VCAM-1, in accordance with the results that MAIR-II associated with FcRγ chain, but not DAP12 after LPS stimulation.

Figure 6. iMo require FcRγ chain and Syk for migration into the peritoneal cavity after CLP.

(a,c) iMo from WT, AF251705−/−, Tyrobp−/− or Fcer1g−/− mice were incubated on human IgG1-precoated or VCAM-1-Fc-precoated plates in the presence or absence of LPS for 20 h, and adherent cells were counted by means of microscopy (n=3 per group). Scale bars, 100 μm. (b) iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were incubated in the presence or absence of LPS for 20 h, subjected to flow adhesion assays to VCAM-1-Fc or human IgG1-coated glass capillaries, and then adherent cells were counted by means of microscopy (n=3 per group). (d) CFSE-labelled iMo from WT, AF251705−/−, Tyrobp−/− or Fcer1g−/− mice were transferred intravenously into AF251705−/− mice 20 h after CLP. Migrated CFSE+ iMo in the peritoneal cavity were counted by using flow cytometry 20 h after CLP (n=7, 9 or 13 per group). (e) iMo from WT, AF251705−/−, Tyrobp−/− or Fcer1g−/− mice were transferred intravenously into AF251705−/− mice immediately before CLP. Mice were monitored every 6 h for 6 days to determine survival (n=6, 7, 3 or 5 per group). (f) iMo from WT or AF251705−/− mice were stimulated with LPS on VCAM-1-Fc-precoated plates in the presence or absence of piceatannol, a Syk inhibitor, for 20 h, and adherent cells were counted by means of microscopy (n=3 per group). (g) iMo from WT or Myd88−/− mice were left unstimulated or stimulated with LPS for 20 h, and the expression of Fcer1g and Tyrobp mRNA was analysed by using real-time reverse transcription–PCR (n=3 per group). (h) iMo from WT or Myd88−/− mice were incubated on VCAM-1-Fc-precoated plates in the presence or absence of LPS for 20 h, and adherent cells were counted by means of microscopy (n=3 per group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test in (a–d,f–h)) and log-rank test in e). N.S., not significant. Error bars indicate s.d. Data are representative of two independent experiments. See also Supplementary Figs 9 and 10.

To examine whether FcRγ chain-mediated Syk activation is required for iMo adhesion to VCAM-1, WT or AF251705−/− iMo were incubated on culture dishes precoated with VCAM-1-Fc in the presence or absence of piceatannol, a Syk inhibitor. Piceatannol suppressed iMo adhesion to VCAM-1-Fc in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 10a,b), suggesting that Syk activation is required for LPS-induced iMo adhesion to VCAM-1.

E-selectin-mediated integrin activation was regulated via the activation of Syk, subsequent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk), phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phospholipase C (PLC) γ2 (ref. 33). We examined whether these molecules in the downstream of Syk were also involved in the adhesion of iMo to VCAM-1-Fc by using an inhibitor of the activity for each molecule. Incubation of WT iMo in the presence of PCI-32765 (a Btk inhibitor), Wortmannin and LY294002 (both phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors), or U-73122 (a PLC inhibitor) showed significantly impaired adhesion to VCAM-1-Fc, which was comparable with AF251705−/− iMo (Supplementary Fig. 10c). These results suggest that MAIR-II expressed on iMo regulates TLR4-mediated cell adhesion to VCAM-1 via the activation of Syk.

MyD88 regulates FcRγ and DAP12 expression and iMo adhesion

We have shown that the migration of iMo from Tlr4−/− and Myd88−/− mice into the peritoneal cavity was impaired compared with WT iMo, and that these mice showed significantly shorter survival than WT mice after CLP (Fig. 4). Furthermore, LPS stimulation upregulated FcRγ chain expression and downregulated DAP12 expression and adhesion of iMo to VCAM-1. To directly show that LPS-mediated signalling via MyD88 is involved in the regulation of the expression of both FcRγ chain and DAP12, and the adhesion of iMo to VCAM-1, iMo derived from WT or Myd88−/− mice were stimulated with LPS. In accordance with the results shown in Fig. 5c, LPS stimulation increased Fcer1g expression but decreased Tyrobp expression in WT iMo (Fig. 6g). However, the expression of Fcer1g and Tyrobp was not altered in iMo from Myd88−/− mice (Fig. 6g). Moreover, although LPS stimulation enhanced binding of WT iMo to VCAM-1-Fc, it did not enhance the binding of Myd88−/− iMo (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 10d). These results indicate that MyD88 is required for the regulation of FcRγ chain and DAP12 expression, and the adhesion of iMo to VCAM-1.

Discussion

In the present study, we first showed that TLR4/MyD88 signalling is essential for iMo recruitment from the blood to sites infected with Gram-negative bacteria via VLA-4. We further showed that TLR4/MyD88-mediated signalling upregulated FcRγ chain expression, and induced physical and functional association of TLR4/MyD88 with MAIR-II, FcRγ chain and Syk, leading to activation of VLA-4 in iMo (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. A proposed model of TLR4-mediated regulation of iMo migration.

TLR4/MyD88-mediated signalling upregulated FcRγ chain expression but downregulated DAP12 expression, and induced physical and functional association of TLR4/MyD88 with MAIR-II, FcRγ chain, and Syk, leading to activation of VLA-4 in iMo. See also text.

Previous studies have demonstrated that TLR4 is coimmunoprecipitated with CD16 (Fcγ receptor III), an FcRγ chain-coupled immunoreceptor, in neutrophils and macrophages after stimulation with LPS or IgG immune complex34. Interestingly, neutrophils and macrophages from Tlr4−/− mice were unresponsive to either LPS or IgG immune complex for cytokine production and the tyrosine phosphorylation of FcRγ chain on stimulation of CD16 with IgG immune complex34, suggesting that TLR4 is indispensable for CD16 signalling via FcRγ chain activation. Although it remains undetermined how TLR4 associates with CD16 and MAIR-II, FcRγ chain may play a key role in the link between TLR4 and MAIR-II or CD16. As LPS stimulation induces activation of the Src family of kinases, a family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases35, it is possible that activated Src kinases phosphorylate the tyrosine of ITAM in FcRγ chain. Interestingly, we showed that another FcRγ chain-interacting mouse CD300 molecule CLM-5/MAIR-IV/LMIR4 also associated with TLR4 after stimulation with LPS. In contrast, we did not observe the association of TLR4 with CD300f that also interacts with FcRγ chain (Supplementary Fig. 7). It is unclear at present whether FcRγ chain is involved in this association. Further studies are required to clarify the molecular basis of the association of TLR4 with FcRγ chain-coupled immunoreceptors.

Immunoreceptors containing positively charged amino acids in the transmembrane regions, present on lymphocytes and myeloid cells, are able to non-covalently associate with any of the ITAM-bearing signalling adaptors DAP12, FcRγ chain, DAP10 or CD3ζ; exceptionally, the NK receptor NKG2D can bind to both DAP12 and DAP10 in T cells36. MAIR-II is a unique immunoreceptor that binds either DAP12 or FcRγ chain (expressed on peritoneal macrophages, but not macrophages or B cells in the spleen) via a lysine residue located in the transmembrane region of MAIR-II17. We have shown that LPS stimulation upregulates FcRγ chain expression17, leading to the preferential association of MAIR-II with FcRγ chain. A previous report demonstrated that LPS stimulation of macrophages activates interferon regulatory factor-8 (ref. 37), which downmodulates Tyrobp transcription and DAP12 expression38. This is one possible explanation for why DAP12 expression is downregulated in iMo by stimulation with LPS. In contrast, the expression of FcRγ chain is regulated by multiple transcription factors, including Sp1, GABP and Elf-1 (ref. 39). However, it is unclear at present whether TLR4 signalling is involved in the transcription mechanism of Fcer1g.

We have shown that MAIR-II regulates TLR4-mediated cell adhesion to VCAM-1 in highly purified iMo (in the present study) or cytokine production in B cells (in a previous report18) in response to TLR ligands alone, suggesting that a ligand for MAIR-II may be expressed on iMo and B cells, or induced after TLR ligand stimulation, resulting in cis-binding between MAIR-II and the ligand. Recent studies suggest that CD300 and the TREM family proteins physically bind to phospholipids40. These molecules are preferentially expressed on myeloid cells, whose membrane phospholipids are dynamically remodelled on stimulation with innate stimuli such as TLR ligands41, suggesting functional bindings between CD300 and the TREM family proteins. Indeed, ourselves and others have recently identified phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of apoptotic cells as a ligand for mouse and human CD300a42,43. Moreover, CD300f is reported to also bind to several extracellular lipids, including phosphatidylserine, ceramide and lipoproteins44,45,46. Therefore, it is possible that MAIR-II may also bind to phospholipids as functional ligands. Our previous study demonstrated that unlike CD300a, MAIR-II does not bind phosphatidylserine47. Further studies are required for the clarification of MAIR-II function in vivo.

Methods

Mice

BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Clea Japan. AF251705−/− mice were generated in our laboratory and backcrossed onto the C57BL/6J genetic background for 12 generations18. C57BL/6.SJL (Ptprca Pepcb, CD45.1+) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Myd88−/− and Tlr4−/− mice in a BALB/c background were purchased from Oriental Bioservice. Tyrobp−/− and Fcer1g−/− mice were provided by Toshiyuki Takai (Tohoku University, Japan) and backcrossed onto the C57BL/6J genetic background for 12 generations as described17,48,49. All mice used were 8–12 weeks old female or male. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the animal ethics committee of the University of Tsukuba Animal Research Center.

Caecal ligation and puncture

CLP was performed as described42,50. The caecum was exposed by a 1- to 2-cm midline incision in the ventral abdomen, ligated at ~7 mm from its distal portion and punctured twice with a 25-gauge needle in the ligated segment. The abdomen was closed in two layers, and 1 ml of sterile saline was administered subcutaneously. Sham-operated mice were subjected to a similar laparotomy without ligation and puncture. Peritoneal lavage fluid and plasma from mice 8 and 20 h after CLP, respectively, were collected for analyses of cytokine and chemokine levels. To determine bacterial loads after CLP, peritoneal lavage fluid from mice 20 h after CLP was placed on ice and serially diluted in sterile PBS. A 100-μl aliquot of each dilution was spread on Brain Heart Infusion agar plates without antibiotics and incubated under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h.

Measurement of cytokines and chemokines

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations were measured in triplicate by using ELISA kits purchased from BD Biosciences (TNF-α and IL-6) and R&D Systems (CCL2).

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

mAbs against mouse CD11b, Ly6G, Ly6C, CD45.1, CD45.2 and LFA-1 (CD11a) (M1/70, 1A8, AL-21, A20, 104 and M17/4, respectively) were purchased from BD Biosciences. mAbs against mouse F4/80 (Cl:A3-1), CCR2 (475301) and VLA-4 (PS/2) were purchased from AbD Serotec, R&D Systems and Abcam, respectively. mAbs against mouse MAIR-II (TX52) were generated in our laboratory as described16,17. mAbs diluted at 10~50 times with PBS were used for flow cytometric analysis by using a FACSCalibur or an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Boscience). For in vivo analyses, 100 μg of anti-LFA-1 or anti-VLA-4 were injected intravenously into mice. Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star) was used for data analysis.

Depletion of macrophages and monocytes

For in vivo depletion of Mφ/Mo, mice were injected intravenously with 200 μl PBS-liposomes or Cl2MBP-liposomes (Encapsula NanoSciences) 1 day before CLP, as described51.

Isolation of iMo and adoptive transfer

iMo were purified from bone marrow cells by positive selection using a MACS cell separation system (Miltenyi Biotec) with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CCR2 mAb and anti-allophycocyanin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of iMo, which were determined as CD11b+ Ly6Chigh cells, was >90%. For adoptive transfer, iMo were transferred by intravenous inoculation of 1 × 106 cells into the orbital venous plexus of AF251705−/− mice immediately before CLP. To trace the transferred iMo, the cells were labelled with CFSE (Molecular Probes) before adoptive transfer.

Biochemical analysis

RAW264.7 transfectants stably expressing Flag-tagged CD300a or Flag-tagged MAIR-II were generated as described16, and incubated in RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% fetal bovine serum with or without LPS (O55:B5; Sigma-Aldrich) (1 μg ml−1) for 20 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 1% digitonin (Calbiochem) supplemented with protease inhibitors as described17. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-TLR4 polyclonal antibodies (L-14; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Flag polyclonal antibodies (F7425; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-DAP12 polyclonal antibodies (FL-113; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-FcRγ chain polyclonal antibodies (06–727; Millipore). Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS–PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by electroblotting, immunoblotted with polyclonal antibodies against Flag, TLR4, DAP12, FcRγ chain (T2040; US Biological), tyrosine phosphorylated Syk (Tyr525/526) (2710; Cell Signaling) or Syk (2712; Cell Signaling), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-goat IgG (sc-2768; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or HRP-conjugated TrueBlot anti-rabbit IgG (18-8816-33; eBioscience). In some cases, HRP-conjugated anti-phosphorylated tyrosine mAbs (4G10; Millipore) was used for immunoblotting.

Complementary DNA synthesis and real-time reverse transcription–PCR

Total RNA was extracted with Isogen reagent (Nippon Gene), and cDNA was synthesized by using a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time reverse transcription–PCR was performed with gene-specific primers (Supplementaly Table 2) and SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems). Expression of each target gene was normalized to that of β-actin.

Cell adhesion analysis

For static adhesion assay, culture dishes (NUNC, 35 × 10 mm) were precoated with human IgG1 antibody (AG502; Millipore) or mouse VCAM-1-Fc (643-VM; R&D Systems) (2 μg ml−1) for 16 h, washed with PBS and blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. iMo (4 × 105 per dish) were plated on the culture dishes and incubated in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg ml−1) for 20 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were then gently removed by washing with PBS, the numbers of adherent cells in five fields were counted under BZ-9000 All-in One Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence) ( × 20) and the mean number of adherent cells were calculated. For analysis of the involvement of kinases in iMo adhesion to VCAM-1, inhibitors of Syk (Piceatannol; Sigma-Aldrich), Btk (PCI-32765; Selleck Chemicals), PI3 kinase (Wortmannin and LY294002; both from Wako Pure Chemical Industries) or PLC (U-73122; Calbiochem) were added into the culture media before incubation and iMo adhesion was assessed as described above.

Flow adhesion assay was performed as described previously32. Briefly, the inner surface of 0.69-mm-diameter glass capillaries (Drummond) was coated with VCAM-1-Fc or human IgG1 (20 μg ml−1 each) at 4 °C overnight and blocked with fetal bovine serum at room temperature for 5 min. iMo (0.8 × 106 cells per ml) resuspended in RPMI1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum were infused into the capillaries at a shear stress of 0.20 dyne c−1 m−2 at 37 °C. The rate of flow was controlled by a Harvard PHD 2000 syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus). After 4-min stabilization period, the cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope (Olympus IX70) and the number of adhered cells in a 0.60-mm2 microscope field was determined at a 40-s interval.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between groups was determined by using the two-tailed Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism). Bacterial counts of mice subjected to CLP were analysed by using the Mann–Whitney U-analysis (GraphPad Prism). Mortality of mice subjected to CLP was analysed by using Kaplan–Meir survival curves and the log-rank test (GraphPad Prism). Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Author contributions

N.T. conducted the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. Y.-G.K. designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. K.K., K.N. and E.U. performed the experiments and analysed the data, S.T.-H. and M.M. designed the experiments and analysed the data. C.N.-O. generated the AF251705−/− mice and analysed the data. S.H. and K.S. analysed the data. A.S. supervised the overall project and wrote the paper.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Totsuka, N. et al. Toll-like receptor 4 and MAIR-II/CLM-4/LMIR2 immunoreceptor regulate VLA-4-mediated inflammatory monocyte migration. Nat. Commun. 5:4710 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5710 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-10, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary Reference

WT iMo adhesion in the absence of LPS. iMo from WT mice were incubated in the absence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

AF251705-/- iMo in the absence of LPS. iMo from AF251705-/- mice were incubated in the absence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

WT iMo adhesion in the presence of LPS. iMo from WT mice were incubated in the presence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

AF251705-/- iMo adhesion in the presence of LPS . iMo from AF251705-/- mice were incubated in the presence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Mitsuishi and Y. Nomura for secretarial assistance, and the members of the laboratory for their discussions. This work was supported in part by grants provided by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- Gordon S. & Taylor P. R. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 953–964 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F., Jung S. & Littman D. R. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19, 71–82 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley-Bauer L. P., Wynn G. M. & Mocarski E. S. Cytomegalovirus impairs antiviral CD8+ T cell immunity by recruiting inflammatory monocytes. Immunity 37, 122–133 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C. & Pamer E. G. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 762–774 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. G. et al. The Nod2 sensor promotes intestinal pathogen eradication via the chemokine CCL2-dependent recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Immunity 34, 769–780 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunay I. R. et al. Gr1(+) inflammatory monocytes are required for mucosal resistance to the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity 29, 306–317 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima N., Mattei L. M. & Iwasaki A. Recruited inflammatory monocytes stimulate antiviral Th1 immunity in infected tissue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 284–289 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swirski F. K. et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science 325, 612–616 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swirski F. K. et al. Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 195–205 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedi K. et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 70, 5728–5739 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocuin L. M. et al. Neutrophil IL-10 suppresses peritoneal inflammatory monocytes during polymicrobial sepsis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 89, 423–432 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbina N. V. & Pamer E. G. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat. Immunol. 7, 311–317 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. R., Hyduk S. J. & Cybulsky M. I. Chemoattractants induce a rapid and transient upregulation of monocyte alpha4 integrin affinity for vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 which mediates arrest: an early step in the process of emigration. J. Exp. Med. 193, 1149–1158 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. B., Hobbs J. A., Mathies M. & Hogg N. Rapid recruitment of inflammatory monocytes is independent of neutrophil migration. Blood 102, 328–335 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K., Laudanna C., Cybulsky M. I. & Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 678–689 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsumoto K. et al. Paired activating and inhibitory immunoglobulin-like receptors, MAIR-I and MAIR-II, regulate mast cell and macrophage activation. J. Exp. Med. 198, 223–233 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi C. et al. Dual assemblies of an activating immune receptor, MAIR-II, with ITAM-bearing adapters DAP12 and FcRgamma chain on peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 178, 765–770 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano-Yokomizo T. et al. The immunoreceptor adapter protein DAP12 suppresses B lymphocyte-driven adaptive immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1661–1671 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai H. et al. Identification and characterization of a new pair of immunoglobulin-like receptors LMIR1 and 2 derived from murine bone marrow-derived mast cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 719–729 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D. H. et al. CMRF-35-like molecule-1, a novel mouse myeloid receptor, can inhibit osteoclast formation. J. Immunol. 171, 6541–6548 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T. et al. Activation of neutrophils by a novel triggering immunoglobulin-like receptor MAIR-IV. Mol. Immunol. 45, 289–294 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark G. J., Cooper B., Fitzpatrick S., Green B. J. & Hart D. N. The gene encoding the immunoregulatory signaling molecule CMRF-35A localized to human chromosome 17 in close proximity to other members of the CMRF-35 family. Tissue Antigens 57, 415–423 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Q. T. et al. Blockade of CD137 signaling counteracts polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture. Infect. Immun. 77, 3932–3938 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Filho J. C. et al. Interleukin-33 attenuates sepsis by enhancing neutrophil influx to the site of infection. Nat. Med. 16, 708–712 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck-Palmer O. M. et al. Deletion of MyD88 markedly attenuates sepsis-induced T and B lymphocyte apoptosis but worsens survival. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83, 1009–1018 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supajatura V. et al. Differential responses of mast cell Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in allergy and innate immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 1351–1359 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego F. The CD300 molecules: an emerging family of regulators of the immune system. Blood 121, 1951–1960 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocsai A., Ruland J. & Tybulewicz V. L. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 387–402 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbock A., Lowell C. A. & Ley K. Spleen tyrosine kinase Syk is necessary for E-selectin-induced alpha(L)beta(2) integrin-mediated rolling on intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Immunity 26, 773–783 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarbock A. et al. PSGL-1 engagement by E-selectin signals through Src kinase Fgr and ITAM adapters DAP12 and FcR gamma to induce slow leukocyte rolling. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2339–2347 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews R. P., Kepley C. L., Youssef L., Wilson B. S. & Oliver J. M. Regulation of the very late antigen-4-mediated adhesive activity of normal and nonreleaser basophils: roles for Src, Syk, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Leukoc. Biol. 70, 776–782 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto E. et al. Nepmucin, a novel HEV sialomucin, mediates L-selectin-dependent lymphocyte rolling and promotes lymphocyte adhesion under flow. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1603–1614 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller H. et al. Tyrosine kinase Btk regulates E-selectin-mediated integrin activation and neutrophil recruitment by controlling phospholipase C (PLC) gamma2 and PI3Kgamma pathways. Blood 115, 3118–3127 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittirsch D. et al. Cross-talk between TLR4 and FcgammaReceptorIII (CD16) pathways. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000464 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev A. E. et al. Role of TLR4 tyrosine phosphorylation in signal transduction and endotoxin tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16042–16053 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilfillan S., Ho E. L., Cella M., Yokoyama W. M. & Colonna M. NKG2D recruits two distinct adapters to trigger NK cell activation and costimulation. Nat. Immunol. 3, 1150–1155 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. et al. IRF-8/interferon (IFN) consensus sequence-binding protein is involved in Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and contributes to the cross-talk between TLR and IFN-gamma signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10073–10080 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orabona C. et al. Toward the identification of a tolerogenic signature in IDO-competent dendritic cells. Blood 107, 2846–2854 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. et al. Cooperative regulation of Fc receptor gamma-chain gene expression by multiple transcription factors, including Sp1, GABP, and Elf-1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15134–15141 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon J. P., O’Driscoll M. & Litman G. W. Specific lipid recognition is a general feature of CD300 and TREM molecules. Immunogenetics 64, 39–47 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-de-Gomez L. et al. A phosphatidylinositol species acutely generated by activated macrophages regulates innate immune responses. J. Immunol. 190, 5169–5177 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi-Oda C. et al. Apoptotic cells suppress mast cell inflammatory responses via the CD300a immunoreceptor. J. Exp. Med. 209, 1493–1503 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simhadri V. R. et al. Human CD300a binds to phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine, and modulates the phagocytosis of dead cells. Blood 119, 2799–2809 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa K. et al. The receptor LMIR3 negatively regulates mast cell activation and allergic responses by binding to extracellular ceramide. Immunity 37, 827–839 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. C. et al. Cutting edge: mouse CD300f (CMRF-35-like molecule-1) recognizes outer membrane-exposed phosphatidylserine and can promote phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 187, 3483–3487 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L. et al. p85alpha recruitment by the CD300f phosphatidylserine receptor mediates apoptotic cell clearance required for autoimmunity suppression. Nat. Commun. 5, 3146 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi-Oda C., Tahara-Hanaoka S., Honda S., Shibuya K. & Shibuya A. Identification of phosphatidylserine as a ligand for the CD300a immunoreceptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 646–650 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaifu T. et al. Osteopetrosis and thalamic hypomyelinosis with synaptic degeneration in DAP12-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 323–332 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T., Li M., Sylvestre D., Clynes R. & Ravetch J. V. FcR gamma chain deletion results in pleiotrophic effector cell defects. Cell 76, 519–529 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittirsch D., Huber-Lang M. S., Flierl M. A. & Ward P. A. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat. Protoc. 4, 31–36 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N. The liposome-mediated macrophage ‘suicide’ technique. J. Immunol. Methods 124, 1–6 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-10, Supplementary Tables 1-2 and Supplementary Reference

WT iMo adhesion in the absence of LPS. iMo from WT mice were incubated in the absence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

AF251705-/- iMo in the absence of LPS. iMo from AF251705-/- mice were incubated in the absence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

WT iMo adhesion in the presence of LPS. iMo from WT mice were incubated in the presence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.

AF251705-/- iMo adhesion in the presence of LPS . iMo from AF251705-/- mice were incubated in the presence of LPS for 20 h and subjected to flow adhesion assay to VCAM-1-Fc-coated glass capillaries. Cells were monitored under an inverted light microscope. See also Fig. 6b.