Abstract

Development of long-term implantable luminescent biosensors for subcutaneous oxygen has proved challenging due to difficulties in immobilizing a biocompatible matrix that prevents sensor aggregation yet maintains sufficient concentration for transdermal optical detection. Here, we demonstrate that Pd-porphyrins can be used as PEG crosslinkers to generate a polyamide hydrogel with extreme porphyrin density (~5 mM). Dye aggregation was avoided due to the spatially constraining 3-D mesh formed by the porphyrins themselves. The hydrogel exhibited oxygen-responsive phosphorescence and could be stably implanted subcutaneously in mice for weeks without degradation, bleaching or host rejection. To further facilitate oxygen detection using steady state techniques, we developed an oxygen non-responsive companion hydrogel by blending copper and free base porphyrins to yield intensity-matched luminescence for ratiometric detection.

Keywords: hydrogels, porphyrins, imaging, oxygen sensing, phosphorescence, implants

1. Introduction

Oxygen plays a vital role in physiological processes and abnormal levels are linked with a multitude of pathologies such as cerebral,[1] cardiovascular,[2] and neoplastic[3] diseases. Appropriate subcutaneous tissue oxygenation is essential for wound healing.[4] To date, few minimally invasive methods have been described for monitoring of oxygen directly in subcutaneous tissue that are suitable for long-term monitoring. A variety of methods have emerged to gauge the concentration of oxygen in tissues in vivo, such as direct transdermal insertion of electrodes and probes, and examination of optical and magnetic properties of blood.[5] Non-invasive methods based on oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin optical and magnetic properties are widely used, but only examine blood oxygenation within vessels, which is not a necessarily a reliable indicator of tissue oxygenation. Perhaps the most direct methods to measure tissue oxygenation are electrochemical and phosphorescence quenching methods, both of which involve the use of exogenous probes or sensors.[5] Electrochemical methods are effective for in vivo measurements, but necessitate the use of probes that pass from inside the body to outside, making long term monitoring challenging.[6] Phosphorescence quenching based on triplet state relaxation by molecular oxygen have proven useful for oxygen sensing. Porphyrins are known as excellent theranostic agents[7] and Ru(II)-,[8] Pd(II)-,[9] and Pt(II)- [10,11] porphyrins, have been validated as oxygen responsive probes. These molecules have near infrared (NIR) emission, high stability, long life-times, and good biocompatibility.[12–15] Pd- and Pt- porphyrin derivatives have emerged as an accurate method to measure oxygenation in cell cultures[16–18] and in vivo,[19–22] being well-suited to examine levels of hypoxia within tumors.[23–25] Recent advances have used nanoparticles and microparticles for in vivo oxygen sensing applications.[26] Despite their successful use for some in vivo applications, longer-term phosphorescence quenching methods generally are limited by: 1) lack of techniques for biocompatible immobilization of the porphyrin sensor within the target tissue and 2) difficulties in obtaining an immobilized porphyrin in sufficient concentration to permit transdermal phosphorescence detection. Hydrogels are hydrophilic, water-swollen polymers ideal for implantation and have numerous diverse applications in fields such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, and have been explored as doped sensors for sensing applications.[27–34] Luminescence quenching has also been explored in other potentially implantable materials such as silicone, but such approaches face the same challenges for in vivo implantation and transdermal detection.[35] We recently demonstrated that polyethylene glycol (PEG) diamines could be condensed with free base non-metallo tetracarboxy porphyrins, resulting in a bright and biocompatible polyamide polymer resistant to degradation following weeks of implantation in vivo.[36] Based on this work, we set out to examine Pd-porphyrins as active cross-linkers to generate an oxygen responsive hydrogel for use as an implantable, oxygen-responsive phosphorescent biomaterial.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Pd-mTCPP Hydrogel Synthesis and Characterization

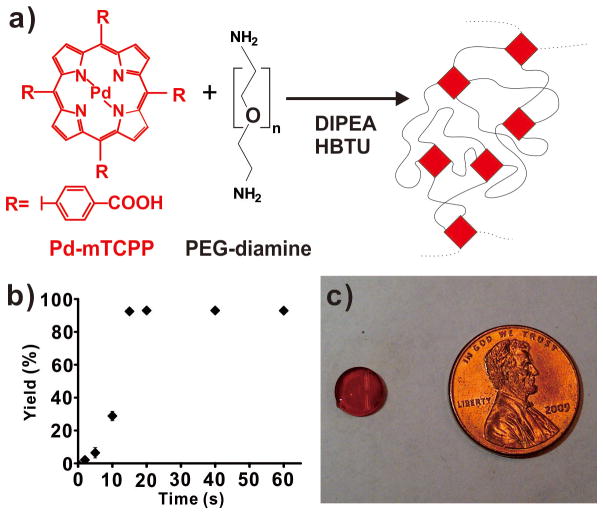

Based on the oxygen-sensitive phosphorescence of Pd-porphyrins, Pd-meso-tetra(carboxyphenyl) porphine (Pd-mTCPP) was used a crosslinker for PEG diamines (Figure 1a). The resulting polymer was predicted to have a highly interconnected mesh form, resulting in the spatial segregation of the porphyrins (Figure 1b). The polymerization was carried out in dimethylformamide (DMF) using O-benzotriazol-1-yl-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) as a coupling agent and the reaction was initiated with diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) as a base. Pd-mTCPP, PEG-diamines and HBTU were added in a 1:2:4 ratio to achieve stoichiometric ratios of acid, base and coupling agent groups. Addition of 0.5 % DIPEA was sufficient to initiate a rapid polymerization (Figure S1). The reaction completed within 20 seconds, resulting in the covalent incorporation of > 95% of the free Pd-mTCPP into the polymer network. Next, the hydrogel was generated by incubating the polymer in water to remove all DMF from the gel. The 8 mm diameter hydrogel had a smooth and reflective surface and was deeply red as a result of the extreme concentration of 5 mM Pd-mTCPP that actively formed the unique mesh network of the hydrogel (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Pd-porphyrins as effective PEG crosslinkers to generate a hydrogel with extreme (~5 mM), spatially segregated porphyrin density.

a) Chemical structures of Pd-mTCPP and PEG-diamines and the schematic polymer network formed following condensation. b) Rapid and complete polymerization of the PEG and porphyrin following addition of DIPEA to initiate the reaction. Mean +/− std. dev. shown for n=3. c) Photograph of an 8 mm hydrogel.

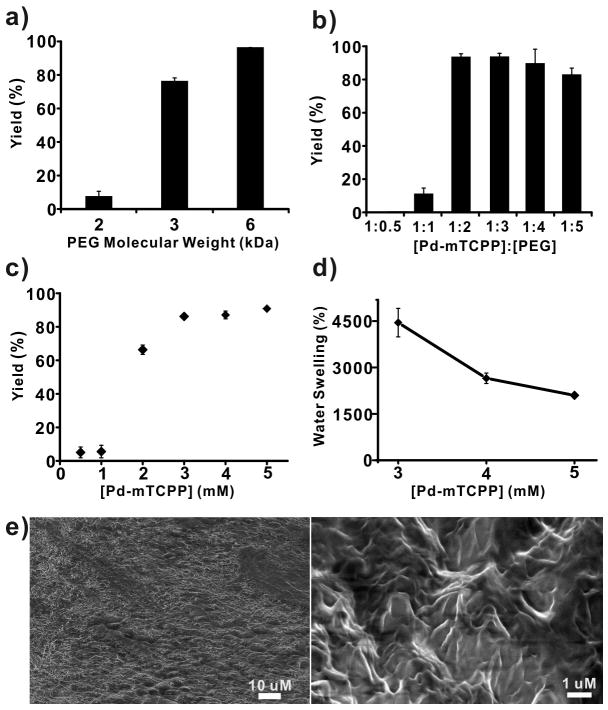

Next, the properties of Pd-mTCPP hydrogel formation were examined. As shown in Figure 2a, as the molecular weight of the PEG diamines decreased from 6K to 2K, the polymerization efficiency declined from over 95% to less than 10%. This demonstrates that the unique three dimensional mesh framework of the Pd-mTCPP hydrogels required appropriate spacing distances between alternating PEG and porphyrin units to polymerize effectively. It noteworthy that in these expriments, lack of incorporation of Pd-mTCPP into the insoluble hydrogel does not imply that polymerization was not occurring, but rather the conditions were not appropriate for achieving a single, massively interconnected and insoluble polymer. Since PEGs carrying 2 amine groups and porphyrins carrying 4 carboxy groups were the main connective elements to the polymer, the ratio between these molecules was critical. As expected, a molar ratio of 1:2 (Pd-mTCPP:PEG-diamine) provided the highest full polymerization efficiency, since this corresponds to the stoichiometric ratio of the functional groups (Figure 2b). The concentration of Pd-mTCPP also played a vital role in the reaction. As shown in Figure 2c, with the ratio between Pd-mTCPP:PEG-diamine:HBTU fixed at 1:2:4, hydrogel generation efficiency declined dramatically as the Pd-mTCPP concentration decreased to below 2 mM in the reaction solution. Again, this points to the requirement of a well-defined spatial arrangement between PEG and porphyrin units in the three dimensional polymer mesh. Amongst the concentrations that permitted effective polymerization (3, 4, and 5 mM Pd-mTCPP), the resulting gels displayed markedly different water swelling ratios ranging from ~4500% for the 3 mM concentration to ~2000% for the 5 mM hydrogel. Scanning electron micrographs revealed a hydrogel with a relatively smooth macroscale surface in accordance to the optically reflective hydrogel shown in Figure 1c. At higher magnifications, distinct sub-micron sized features were apparent, supporting the existence of a disordered but highly interconnected porphyrin-PEG environment (Figure 2e).

Figure 2. Characterization of Pd-porphyrin hydrogel formation.

In otherwise equivalent conditions, polymer yield was affected by a) PEG diamine size; b) Ratio of Pd-mTCPP to PEG-diamine (6K); and c) Pd-mTCPP concentration (with constant ratios of PEG:porphyrin:HBTU). d) Water swelling as a function of Pd-mTCPP concentration during polymerization. Mean +/− std. dev. shown for n=3. e) SEM of a freeze-dried portion of Pd-mTCPP hydrogel.

Pd-mTCPP hydrogels featured a typical porphyrin absorption with a Soret band at 416 nm and a lesser Q-band at 523 nm and produced long wavelength phosphorescence around 705 nm. Due to spatial constraint in the matrix, strong luminescence quenching was avoided, which can occur at due to porphyrin-porphyrin interaction at high densities.[37] The hydrogel responses to varying oxygen levels was measured by adsorbing the gel to the side of a water filled cuvette with bubbling gas and probing the phosphorescence response either in a fluorometer or with a bifurcated optical fiber for lifetime measurements. As shown in Figure 3a, by changing the environment of the hydrogel from pure nitrogen to 10% oxygen, a reversible change in phosphorescence was observed. When oxygen was introduced, the phosphorescence of the hydrogel decreased in approximately 15 seconds. When an oxygen-free enviromenment was reintroduced, the hydrogel responded with an increase in phosphosphorescence over a 30 second period. These response times in the tens of seconds and with the low oxygen conditions taking a longer time for equilibration are in line with previously phosphorescence oxygen sensors.[12,12,13,38,39] Phosphorescent lifetimes were obtained over a wide range of oxygen concentrations using an analog lifetime detection system as previously reported.[40] Phosphorescence lifetimes ranged from 55 μs in oxygen free conditions to 2.4 μs in 60% oxygen (Figure 3b). The Stern Volmer lifetime quenching constant was determined using Equation (1)

Figure 3. Oxygen-responsive phosphorescence of the Pd-porphyrin hydrogel.

a) Reversible steady-state phosphorescence response to oxygen in indicated conditions at 37 °C. b) Characterization of hydrogel phosphorescence lifetime response. c) Stern-Volmer lifetime analysis of hydrogel phosphorescence as a function of oxygen concentration.

| (1) |

Following unit conversion, a KSV value of 38 × 105 Pa−1 was observed, which is similar to previously reported oxygen quenching constants of Pd- and Pt- porphyrins.[41] In this range, which extends well beyond physiological levels of oxygen, the lifetime quenching relationship was linear (with an R2 value of 0.999) in accordance with the Stern-Volmer quenching expected for collisional quenching of the porphyrins by freely diffused molecular oxygen (Figure 3c).

2.2. In vivo implantation of Pd-mTCPP hydrogels

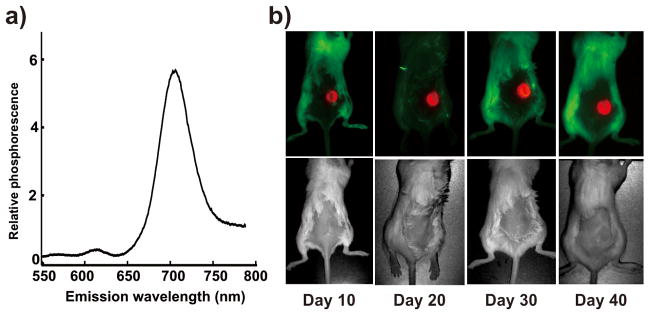

As shown in Figure 4a, the hydrogel phosphorescence peak appeared around 705 nm, a wavelength that is in the near infrared window well-suited for in vivo biological imaging applications.[42] Due to the high porphyrin density that is spatially constrained to prevent self-quenching[36], we hypothesized that measurement of the Pd-porphyrin hydrogel phosphorescence would be possible in vivo. The hydrogel was implanted with a minor surgical procedure that involved making an incision on the back of BALB/c mice, inserting the hydrogel and closing the incision with sutures. In the future, an injectable hydrogel formulation, either through size modification of the existing hydrogel into microparticles or chemical modification of the material would be beneficial to avoid risks and inconvenience associated with minor surgery. The hydrogel was readily detected through the skin on the back of the mouse. Hydrogel luminescence could clearly be detected over the autofluorescence of background using steady state luminescence imaging with a short 200 ms camera exposure. Figure 4b shows the implanted hydrogel luminescence 10 days after implantation, after the sutures had been removed. The hydrogel maintained its shape and bightness over a 40 day period without significant degradation or photobleaching. The mouse remained healthy and did not display any outward signs of toxicity. To our knowedge, this is longest in vivo demonstration of a stable, implantable oxygen-sensitive phosphorescent biomaterial. Other oxygen sensing materials might be rapidly be cleared, degraded or drained by the body, or alternatively at the high concentrations required for transdermal detection might be self-quenched.

Figure 4. Suitability of the Pd-porphyrin hydrogel for in vivo implantation and transdermal imaging.

a) Luminescence emission spectrum in the near infrared of the Pd-porphyrin hydrogel in 20% oxygen. b) Hydrogel was implanted subcutaneously in a BALB/c mouse and imaged every 10 days. Luminescence images are shown in the top row and corresponding white light images are shown in the bottom row. No obvious degradation, photobleaching or toxicity was observed. Images were aquired on a Maestro imager.

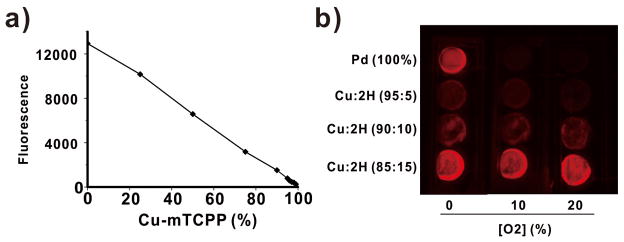

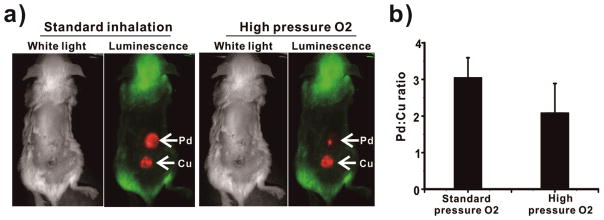

Direct measurement of absolute hydrogel gel phosphorescence intensity in itself does not provide a reliable measure oxygen levels. Phosphorescence lifetime analysis as shown in Figure 3 provides a more robust measure but setup of such a transdermal phosphorescence lifetime imaging system poses significant technical challenges. Therefore, to obtain a simple measure of oxygen levels, ratiometric approaches may be used.[43] We developed a ratiometric approach that compared total Pd-hydrogel luminescence to the luminescence of a non-oxygen responsive fluorescent companion hydrogel. Since freebase porphyrins are orders of magnitude brighter in comparison to Pd-porphyrins (in normal atmospheric conditions), to prevent detector saturation of the free base porphyrin hydrogel, the total luminescence of the freebase porphyrins was attenuated by incorporation of non-luminescent copper tetracarboxy porphyrins (Cu-mTCPP) into the polymer. A series of hydrogels was synthesized with increasing amounts of Cu-mTCPP into a free base porphyrin background (Figure 5a). This approach provided a highly tunable method to generate hydrogels that could have their total NIR luminescence readily attenuated while maintaining the polymer structure. Three of these non-oxygen-responsive fluorescent hydrogels (containing 5, 10, and 15 % freebase-mTCPP with the remaining portion being comprised of non-luminescent copper porphyrins) were examined along with the Pd-porphyrin-hydrogel in atmospheres composed of 0, 10, or 20% oxygen in nitrogen gas (Figure 5b). As expected, the steady state luminescence of the freebase-copper hydrogels did not vary, whereas the Pd-porphyrin hydrogel luminescence increased greatly as oxygen levels decreased while the maximum phosphorescence emission wavelength remained constant (Figure 6b and Figure 6c). The Pd-mTCPP and 15% freebase-mTCPP hydrogels were co-implanted on the back of BALB/c mice, in the subcutaneous space between the skin and the muscle. After the two hydrogels were placed subcutaneously in a small incision, the skin was sutured closed and was allowed to heal for one week. To demonstrate proof of principle for the new paradigm of dual hydrogel transdermal ratiometric imaging, we examined a basic scenarios where subcutaneous oxygen levels changed. Following anesthization of the mouse, the mice were imaged immediately. They were then secured into the nose cone and administered high pressure pure oxygen (3L/min) for 45 minutes. This technique was chosen as it has been demonstrated to increase subcutaneous levels of oxygen in rodents.[44] As shown in Figure 5c, following high pressure oxygen, the the Pd-mTCPP hydrogel became noticeably dimmer whereas the 2H/Cu hydrogel luminescence remained constant. Figure 5d shows that the ratio of the total luminescence of the two hydrogels decreased reproducibly in the subcutaneous following high pressure oxygen exposure. To deal with possible optical interference the light by tissues, future studies should be performed to accurately and quantitatively calibrate the obtained in vivo luminescnece ratios with direct measurement of subcutaneous oxygen using electrode measurements.

Figure 5. A copper-doped, non-oxygen-responsive companion hydrogel for ratiometric imaging.

a) Freebase mTCPP could be titrated with non-luminescent Cu-mTCPP to tune overall hydrogel luminescence. b) Luminescence imaging of Pd-mTCPP and freebase-Cu-mTCPP hydrogels in varying oxygen conditions.

Figure 6. In vivo detection of subcutaneous oxygenation.

a) Transdermal luminescence imaging of dual-implanted Pd-mTCPP and 15% freebase-Cu-mTCPP hydrogels. Left images were taken following anesthetization and right ones taken following high pressure oxygen administration. b) Ratiometric changes in Pd and 2H/Cu luminescence over time following mouse exposure to high pressure inhaled oxygen (error bars show mean +/− std. dev. for n=3 separately implanted and treated mice).

3. Conclusion

We successful used Pd-porphyrins as PEG crosslinkers to generate a novel hydrogel with oxygen-responsive optical properties. The polymerization reaction was fast and effective and resulted in an extreme density porphyrin hydrogel (~5 mM) with a unique three dimensional network that prevented porphyrin aggregation and associated concentration-dependent quenching. Using an intensity matched non-oxygen-sensitive 2H/Cu porphyrin hydrogel, ratiometric imaging was demonstrated in vivo with a companion hydrogel system. Future work will aims to create an injectable hydrogel system to avoid the need for surgical implantation and to develop a hydrogel with an internal ratiometric standard so that a single hydrogel can be implanted instead of two. The advantage of spectrally resolved, internal ratiometric fluoresence callibration has been demonstrated for oxygen sensors.[36,37] The approach of using porphyrins as covalent conjugation sites for dendrimers has recently been demonstrated[47], opening the possibility of creating analagous ultrabright nanoscale porphyrin oxygen sensors.

4. Experimental Section

Synthesis and Characterization of Pd-mTCPP Hydrogel

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise noted. The main components of the hydrogel were Pd-meso-tetra(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (Cat# PdT790, Frontier Scientific) and diamine-functionalized PEG 6K (Cat# 11 6000-2, Rapp Polymere). Unless otherwise stated, this PEG 6K was used. Pd-mTCPP, PEG 6K and the acid activator HBTU (O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate) were dissolved in DMF (N,N-Dimethylformamide) and mixed together with the molar ratio of 1:2:4, at concentrations of 5mM, 10mM and 60mM, respectively. After adding 40μL this solution to a polypropylene 96-well plate, 2μL of 10% DIPEA (N,N-Diisopropylethylamine) in DMF was added to initiate the reaction. The reaction completed within 20 second but was left untouched for at least another 15 minutes. Excess DMF was then added to first stop the solid polymerization reaction and to wash out unincorporated porphyrins and other mateials for 8 hours. The DMF was collected and the absorbance was compared to the original solution to obtain polymerization efficiency. This same basic procedure was used to test the various parameters of hydrogel formation. The influence of PEG size was assessed with PEG 2K and PEG 3K (Cat# 11 2000-2 and 11 3000-2, Rapp Polymer). Following removal of DMF, the hydrogel was placed in water to remove excess DMF overnight and remained stored in water. The hydrogel was freeze-dried for scanning electron micrographs (SEM) and water swelling studies. The Pd-mTCPP hydrogel was frozen rapidly in a dry ice/acetone bath and then transferred to a freeze dryer overnight (Freezone, Labconco) to fully remove all water. Swelling efficiency was calculated as the weight of the water swollen gel compared to the weight of the freeze-dried gel. SEM was performed using the freeze-dried polymer on a stage in a vacuum(Auriga dual beam system, Zeiss).

Optical Properties of the Pd-mTCPP hydrogel

For generating a non-oxygen responsive companion hydrogel, freebase mTCPP and Cu-mTCPP (Cat# T790 and C974, Frontier Scientific) were combined with 0, 20%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 95%, 96%, 97%, 98%, 99% and 100% copper porphyrin. For each well in a 96-well plate, the volume of the mixed solution and HBTU were both 13.3 μL and 2μL of 10% DIPEA in DMF was added. 5 minutes later, 13.4 μL PEG-6K solution was added into into each well and 15 minutes later DMF was used to wash out unincorporated reactants. A fluorescence plate reader was used to measure the fluorescence of the samples using 415 nm excitation and 680 nm emission with 5.0 nm slit widths (Safire plate reader, TECAN). Oxygen measurements were performed in a mixed gas controlled flowcell that achieved desired levels of oxygenation from two externally tanks (nitrogen and oxygen). Steady-state measurements were performed at 40 °C. Excitation wavelength light was provided by a pulsed dye laser source set a 30° angle to the plane of the glass. The laser is pulsed by signal generator and connected to an amplified photodetector (Thorlab PDA-100A) through a lock-in amplifier. Data acquisition was performed in real time using a LabView 8.2 interface. Gas was delivered to the hydrogel by channels within a flowcell with the hydrogel adsorbed to the wall of the cuvette. Luminescence collection was completed by photodiode with a 700 nm bandpass filter. Luminescence photographs were taken in a fluorescence imaging system (Maestro, CRI) after hydrogels had been placed in glass cuvettes containing the indicated oxygen concentrations in a nitrogen background and were sealed with parafilm. All time-resolved intensity decay traces were acquired using an oscilloscope-based time-resolved instrument. The excitation source is a VSL-337 pulsed N2 (g) laser (337 nm, <P> = 2.0 mW, Pmax = 40 kW); detection is achieved by a fast wired photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu, model R928) with the output directed to an oscilloscope (Tektronix, model TDS 350).

In Vivo Studies

Animal experiments were conducted in compliance with University at Buffalo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee policy. Mice were anesthetized with 2 % v/v isoflurane in 100% oxygen carrier gas. Under deep anesthesia, a small incision was made in skin on the back of the mouse and a Pd-mTCPP and a 15% mTCPP / 85% Cu-mtCPP hydrogel were inserted. Sutures (Reli Black Nylon-monofilament Sutures from MYCO Medical Inc., MYCO Catalog number is N931) were used to close the wound. After surgery, luminescence transdermal photos of the hydrogels were taken in the Maetro imager under isoflurane anesthesia as indicated. For high pressure inhaled oxygen, turning the button on the anesthesia machine to change the 100% oxygen flow rate was set to 3 L/min, with the concentration of isoflurane was still 2% v/v. Mice were subjected the gas for 45 minutes before imaging.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Pd-mTCPP hydrogel polymerization efficiency as a function of DIPEA added to initiate the reaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a SUNY RF Collaboration Fund grant.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available online from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Haoyuan Huang, Departments of Biomedical and Chemical and Biological Engineering 201 Bonner Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA.

Wentao Song, Departments of Biomedical and Chemical and Biological Engineering 201 Bonner Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA.

Dr. Guanying Chen, Institute for Lasers, Photonics and Biophotonics 428 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA. Department of Chemistry, 511 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA

Justin M. Reynard, Department of Chemistry, 511 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA

Dr. Tymish Y. Ohulchanskyy, Institute for Lasers, Photonics and Biophotonics 428 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA. Department of Chemistry, 511 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA

Prof. Paras N. Prasad, Institute for Lasers, Photonics and Biophotonics 428 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA. Department of Chemistry, 511 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA

Prof. Frank V. Bright, Department of Chemistry, 511 NSC, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA

Prof. Jonathan F. Lovell, Email: jflovell@buffalo.edu, Departments of Biomedical and Chemical and Biological Engineering 201 Bonner Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, 14260, USA

References

- 1.Zhang K, Zhu L, Fan M. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:1. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmedtje JF, Jr, Ji Y-S. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1998;8:24. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(97)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López-Lázaro M. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:517. doi: 10.2174/187152009788451806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schreml S, Szeimies Rm, Prantl L, Karrer S, Landthaler M, Babilas P. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Springett R, Swartz HM. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2007;9:1295. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolger FB, McHugh SB, Bennett R, Li J, Ishiwari K, Francois J, Conway MW, Gilmour G, Bannerman DM, Fillenz M, Tricklebank M, Lowry JP. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;195:135. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Lovell JF. Theranostics. 2012;2:905. doi: 10.7150/thno.4908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holder E, Oelkrug D, Egelhaaf HJ, Mayer HA, Lindner E. J Fluoresc. 2002;12:383. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu CS. J Lumin. 2013;135:5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briñas RP, Troxler T, Hochstrasser RM, Vinogradov SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11851. doi: 10.1021/ja052947c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obata M, Tanaka Y, Araki N, Hirohara S, Yano S, Mitsuo K, Asai K, Harada M, Kakuchi T, Ohtsuki C. J Polym Sci Part Polym Chem. 2005;43:2997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeh TS, Chu CS, Lo YL. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2006;119:701. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins AN, Wenner BR, Jordan JD, Xu W, Demas JN, Bright FV. Appl Spectrosc. 1998;52:750. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu CS, Lo YL. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2008;134:711. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papkovsky DB, Ponomarev GV, Trettnak W, O’Leary P. Anal Chem. 1995;67:4112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian Y, Shumway BR, Meldrum DR. Chem Mater. 2010;22:2069. doi: 10.1021/cm903361y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian Y, Shumway BR, Gao W, Youngbull C, Holl MR, Johnson RH, Meldrum DR. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2010;150:579. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu H, Jin Y, Tian Y, Zhang W, Holl MR, Meldrum DR. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:19293. doi: 10.1039/C1JM13754A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebedev AY, Cheprakov AV, Sakadz_ic S, Boas DA, Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2009;1:1292. doi: 10.1021/am9001698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson DF, Cerniglia GJ. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakadžić S, Roussakis E, Yaseen MA, Mandeville ET, Srinivasan VJ, Arai K, Ruvinskaya S, Devor A, Lo EH, Vinogradov SA, Boas DA. Nat Methods. 2010;7:755. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanzetta I, Grinvald A. Science. 1999;286:1555. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziemer LS, Lee WMF, Vinogradov SA, Sehgal C, Wilson DF. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1503. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01140.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shonat RD, Wilson DF, Riva CE, Pawlowski M. Appl Opt. 1992;31:3711. doi: 10.1364/AO.31.003711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunphy I, Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. Anal Biochem. 2002;310:191. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meier RJ, Schreml S, Wang X, Landthaler M, Babilas P, Wolfbeis OS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:10893. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiang H, Zhou L, Feng Y, Cheng J, Wu D, Zhou X. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:5208. doi: 10.1021/ic300040n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Wei Z, Xu F, Li YH, Lu TJ, Chen YM, Zhou GJ. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2012;33:1191. doi: 10.1002/marc.201200136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie Z, Ma L, deKrafft KE, Jin A, Lin W. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:922. doi: 10.1021/ja909629f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman AS. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64(Supplement):18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Polymer. 2008;49:1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seliktar D. Science. 2012;336:1124. doi: 10.1126/science.1214804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Zhang B, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Shi J, Zhang XX, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5008. doi: 10.1021/ja402490j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klimant I, Wolfbeis OS. Anal Chem. 1995;67:3160. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovell JF, Roxin A, Ng KK, Qi Q, McMullen JD, DaCosta RS, Zheng G. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3115. doi: 10.1021/bm200784s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, Jin H, Kim C, Rubinstein JL, Chan WCW, Cao W, Wang LV, Zheng G. Nat Mater. 2011;10:324. doi: 10.1038/nmat2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borisov SM, Krause C, Arain S, Wolfbeis OS. Adv Mater. 2006;18:1511. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amao Y, Miyashita T, Okura I. J Fluor Chem. 2001;107:101. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang Y, Tehan EC, Tao Z, Bright FV. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2407. doi: 10.1021/ac030087h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borisov SM, Vasil’ev VV. J Anal Chem. 2004;59:155. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amao Y, Okura I. J Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2009;13:1111. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu C, Bull B, Christensen K, McNeill J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2741. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dewhirst MW, Ong ET, Rosner GL, Rehmus SW, Shan S, Braun RD, Brizel DM, Secomb TW. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1996;27:S241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu H, Aylott JW, Kopelman R, Miller TJ, Philbert MA. Anal Chem. 2001;73:4124. doi: 10.1021/ac0102718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Gorris HH, Stolwijk JA, Meier RJ, Groegel DBM, Wegener J, Wolfbeis OS. Chem Sci. 2011;2:901. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wirotius AL, Ibarboure E, Scarpantonio L, Schappacher M, McClenaghan ND, Deffieux A. Polym Chem. 2013;4:1903. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Pd-mTCPP hydrogel polymerization efficiency as a function of DIPEA added to initiate the reaction.