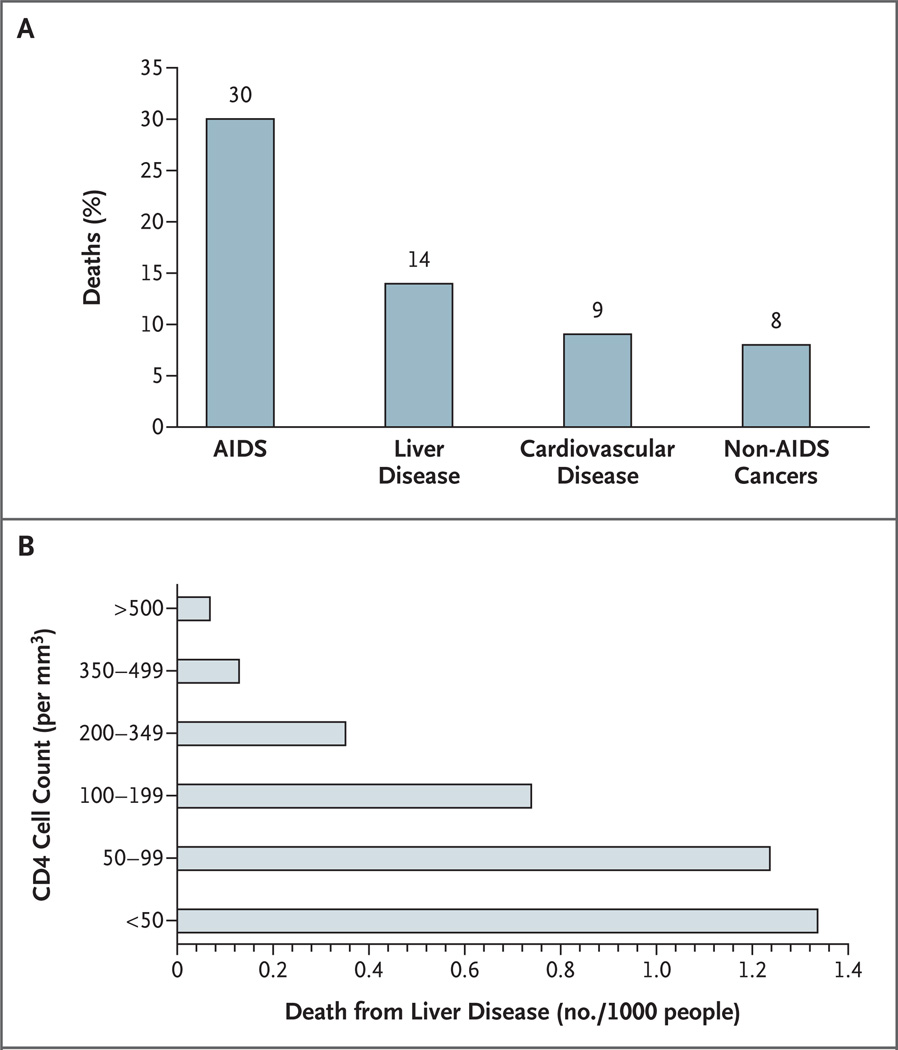

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections are common among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection because of shared routes of viral transmission. Liver disease due to chronic HBV and HCV infection is becoming a leading cause of death among persons with HIV infection worldwide, and the risk of death related to liver disease is inversely related to the CD4 cell count (Fig. 1).1,2 There is also an increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatotoxic effects associated with antiretroviral drugs in patients with HCV and HBV coinfection.1,3–6 New treatments for both HCV and HBV infections have increased the opportunities to manage these infections and potentially prevent complications of liver disease.

Figure 1. Deaths in a Cohort of 23,441 Patients Treated with Anti-HIV Drugs (Panel A) and Deaths from Liver Disease According to the CD4 Cell Count (Panel B).

The data are from the the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs Study, reported by Weber et al.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of coinfection with either HCV or HBV varies depending on the patient’s risk factors for HIV acquisition.7 HCV is most efficiently spread through direct exposure to contaminated blood or blood products. Rates of vertical and perinatal transmission are low, although they are increased in the setting of coinfection.8 Sexual transmission of HCV is inefficient, and the exact risk related to different types of sexual activity is unknown, although there has been increasing recognition of cases of acute HCV infection associated with unsafe sex practices among men who have sex with men.9 In the United States, HIV and HCV coinfection is most prevalent among patients who have a history of either hemophilia or intravenous drug use. Among these patients, rates of coinfection approach 70 to 95%, as compared with 1 to 12% among men who have sex with men.7

Since the rate of clearance of HBV varies according to the patient’s age, the risk of HIV and HBV coinfection depends on the patient’s age at the time of exposure to both viruses. In the United States and Western Europe, HBV is typically acquired during sexual activity in adolescence or early adulthood. Although there is a high rate of spontaneous clearance of HBV (>90%) in immunocompetent adults, chronic infection develops in 20% of adults with HIV infection after exposure to HBV.10 The overall prevalence of chronic HBV infection among HIV-positive persons in the United States and Western Europe is less than 10%, and it is highest among men who have sex with men and among intravenous drug users. In areas where vertical and perinatal transmission of HBV is common, such as Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, chronic HBV infection develops in more than 90% of infants exposed to HBV.11 Thus, the prevalence of HBV infection among HIV-infected persons varies markedly, from 5 to 10% in the United States12,13 to 20 to 30% in Asia and parts of sub-Saharan Africa.14,15

PREVENTING VIRAL HEPATITIS AND MINIMIZING DISEASE

Patients with HIV infection, if nonimmune, should be vaccinated against both hepatitis A virus (HAV) and HBV because of the increased severity of hepatitis in patients with preexisting liver disease.16 Failure to induce immunity to HAV and HBV is a function of both missed opportunities for vaccination17,18 and the immunocompromised state. In HIV-infected persons, antibody titers after vaccination are lower19 and less durable than they are in those who do not have HIV infection, and fewer HIV-infected persons have protective levels of antibodies against hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg).20 The rates of response to HAV or HBV vaccines decrease with lower CD4 cell counts21–23 and higher levels of HIV RNA.18 However, there is no general agreement about when immunization becomes futile. Although there is no vaccine against HCV, education about transmission patterns and safer sex may reduce the incidence of acute HCV infection.9 Finally, clinicians play an important role in counseling patients about transmission, avoidance of alcohol, and limitation of exposure to other hepatotoxic agents (e.g., acetaminophen).

HCV INFECTION

The natural history of HCV infection is accelerated in patients with HIV,24 with an increased rate of progression to cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death.25,26 Immune restoration with combination antiretroviral therapy decreases the rate of death due to liver disease.27 In addition to liver disease, HCV infection is associated with changes in cognitive and psychiatric function,28,29 a decreased quality of life,30 and an increased prevalence of diabetes mellitus,31 all of which potentially affect the management of HIV infection. There are six HCV genotypes, which vary geographically; genotype 1 predominates in North America.32

The effect of HCV infection on the progression of HIV disease is less clear. There are reports of impaired immune reconstitution in patients with HIV and HCV coinfection as compared with those with HIV infection alone33,34; however, this effect appears to be modest and may delay rather than prevent full immune reconstitution.35 Hepatotoxic effects of antiretroviral therapy are more likely to develop in patients with underlying HCV or HBV infection,36 although whether these effects change the time to discontinuation or modification of this therapy is unclear.37,38 Hepatotoxic effects of antiretroviral therapy correlate with the underlying degree of fibrosis.39 Hepatotoxic effects have been described in more detail previously.6,36

ASSESSMENT OF LIVER INJURY

Given the limited response to and toxic effects of current therapy for HCV infection, many experts recommend liver biopsy in most patients to assess the extent of underlying liver damage, to aid in the choice of treatment options, and to provide important prognostic information. In HCV infection, the degree of histologic injury is a better predictor of subsequent clinical events40 than is the degree of elevation of serum aminotransferase levels, the genotype,41 or the viral load.40,42 In one study, 29% of patients with HIV and HCV coinfection and persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels had considerable fibrosis that warranted treatment.43 The biopsy may also reveal steatosis, an independent risk factor for fibrosis in patients with only HCV infection. The association of steatosis with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, HCV genotype 3, use of alcohol, use of antiretroviral drugs, and the lipodystrophy syndrome is poorly understood in patients with HIV infection.44,45

Unfortunately, there is no noninvasive test that accurately predicts either the degree of injury seen on liver biopsy or subsequent clinical events,46 although elastography, a measure of liver stiffness, in combination with serum markers shows promise in the evaluation of fibrosis.47 Patients with cirrhosis should have regular monitoring for evidence of decompensation and liver cancer (Table 1), as well as for a possible referral for liver transplantation.49

Table 1.

Monitoring for Liver Disease in Patients with HIV Infection.*

| Patients | Recommended Test or Procedure |

|---|---|

| At initial evaluation | |

| For HCV | |

| All patients | Test for HCV antibodies |

| Patients with a negative test for HCV antibodies and CD4 cell count <200, persistently elevated aminotransferase levels, or suspected acute hepatitis | Test for HCV RNA† |

| For HBV | |

| All patients | Test for HBsAg, anti-HBs, and anti-HBc (total antibodies) |

| Patients with a positive test for HBsAg or anti-HBc | Test for HBV DNA |

| Patients with a negative test for HBsAg and anti-HBs | Vaccinate against HBV |

| For HAV | |

| All patients | Test for HAV antibodies (total)‡ |

| Patients with a negative test for HAV antibodies | Vaccinate against HAV |

| HCV therapy | |

| At start of therapy | |

| All patients | Measure AST, ALT, albumin, INR, and platelets |

| Test for HCV RNA | |

| Assess genotype (for treatment) | |

| Assess fibrosis stage | |

| During therapy | |

| All patients | Measure CBC and platelets weekly for 4 wk, then measure CBC, platelets, AST, ALT, and uric acid monthly |

| Test for TSH and ANA every 3 mo | |

| Test for HCV RNA before treatment and at 12 wk during and 6 mo after therapy | |

| Patients with a low hemoglobin or neutrophil level | Reduce dose or give erythropoietin or G-CSF during therapy |

| Patients with depression before or during treatment | Give antidepressants as needed |

| Check HCV RNA after 12 wk and discontinue therapy if <2 log10 decrease | |

| HBV therapy | |

| At start of therapy | |

| All patients | Measure AST, ALT, albumin, INR, and platelets |

| Test for HBV DNA, HBeAg, and anti-HBe | |

| During therapy | |

| All patients | Measure AST, ALT, albumin, INR, and platelets and HBV DNA every 3 mo |

| Consider liver biopsy | |

| Monitor creatinine and adjust dose or change therapy if level is abnormal | |

| If patient is receiving nucleotide analogue, monitor phosphate level | |

| Patients with a rise in HBV DNA or ALT level | Check for compliance and resistance |

| Therapy for cirrhosis§ | |

| All patients | Perform liver imaging and alpha-fetoprotein tests every 6–12 mo to evaluate for hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Perform upper endoscopy | |

| Patients with gastroesophageal varices | Give beta-blockers |

| Patients with ascites | Give prophylactic antibiotics weekly |

| Patients with liver decompensation | Refer patient for possible liver transplantation |

AST denotes aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, INR international normalized ratio, CBC complete blood count, TSH thyroid-stimulating hormone, ANA antinuclear antibodies, G-CSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen, anti-HBs antibodies against HBsAg, anti-HBc antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen, and anti-HBe antibodies against HBeAg.

A quantitative test is used to measure HCV RNA at all points in time except for 6 months after treatment, when a qualitative HCV RNA test should be performed.

This test is for total HAV antibodies, not HAV IgM antibodies.

For management guidelines for cirrhosis, see Runyon.48

TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH HIV AND HCV COINFECTION

The current goal of therapy in HCV infection is a sustained virologic response, defined as an undetectable level of serum HCV RNA 6 months after the end of therapy. Studies in patients with HCV monoinfection have confirmed that a sustained virologic response is generally durable50 and that cessation of viral replication results in a reduction in liver injury and possible reversal of fibrosis.51 All patients with fibrosis on liver biopsy should be evaluated for treatment. The current standard of care for patients with HCV monoinfection is pegylated interferon alfa plus ribavirin (Table 2). These agents are not specific for HCV, but they have complex forms of action, including both direct antiviral and immunomodulatory effects.

Table 2.

Therapies for HBV Infection and HCV Infection in HIV-Positive Patients.

| Agent | Antiviral Efficacy and Dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| YMDD-Resistant | |||

| Wild-Type HBV | HBV | HIV | |

| HBV infection* | |||

| Lamivudine | 100 mg | No efficacy | 150 mg twice daily |

| Tenofovir† | 300 mg | 300 mg | 300 mg |

| Tenofovir and emtricitabine† | 300 mg and 200 mg | 300 mg and 200 mg | 300 mg and 200 mg |

| Adefovir | 10 mg | 10 mg | No efficacy |

| Entecavir | 0.5 mg | 1 mg | No efficacy |

| Telbivudine | 600 mg | No efficacy | No efficacy |

| Dose | Duration | ||

| HCV infection (all genotypes) | |||

| Pegylated interferon alfa 2a | 180 µg/wk | 12 mo | |

| Pegylated interferon alfa 2b | 1.5 µg/kg/wk | 12 mo | |

| Ribavirin | Dose based on patient’s weight | 12 mo | |

Doses for HBV infection are total daily doses.

This agent has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for HBV therapy.

For the treatment of infection with HCV genotype 1 or 4, the dose of ribavirin is based on the patient’s weight (1000 mg per day if the weight is <75 kg and 1200 mg per day if the weight is >75 kg); for genotype 2 or 3 infection, ribavirin is given at a lower dose (800 mg per day). For HCV monoinfection, therapy is continued for 48 weeks in patients with genotype 1 or 4 and for 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 or 3.52 With these regimens, sustained virologic responses have been reported in 45 to 55% of patients with genotype 1 or 4 and 80% of those with genotype 2 or 3. A liver biopsy can be deferred in patients with genotype 2 or 3 because of the higher response rates, and it can be limited to those patients without a response to therapy if information about the stage of disease is needed for prognosis and retreatment. Response rates are notably lower in blacks, patients who are obese, patients with cirrhosis, those with genotype 1 or 4, and those with high viral loads (>800,000 IU per milliliter). Weight-based dosing of ribavirin is particularly important for patients who have HCV monoinfection with genotype 1 or 4 and high viral loads.53

Several recent large trials have examined the response rates to pegylated interferon alfa and ribavirin in patients with HIV and HCV coinfection.54–57 Patients in these trials generally received ribavirin at a maximum dose of 800 mg per day.55 Sustained virologic response rates among these patients, who were all treated for 48 weeks irrespective of the genotype, ranged from 14 to 44% for genotype 1 or 4 infection and 44 to 73% for genotype 2 or 3. Treatment was well tolerated. Patients with coinfection had similar dropout rates but required more treatment with growth factors than patients with monoinfection.55,57 A smaller study, using weight-based doses of ribavirin in patients with HIV and HCV coinfection and in those with HCV monoinfection, showed response rates of 18% and 39%, respectively, although the dose of ribavirin was more likely to be reduced in the patients with HIV and HCV coinfection.58

Multiple variables could explain the lower response rates among patients with HIV and HCV coinfection, including the lower dose of ribavirin or dose escalation. One study showed that among patients with coinfection, sustained virologic response rates were lower in those with a high viral load,57 which is common in such patients. The early virologic response (loss of serum HCV RNA or a decrease by at least 2 log10 after 12 weeks of therapy) was validated in patients with coinfection. Thus, if a patient has not had an early virologic response, the likelihood of a sustained virologic response is negligible. Extending therapy in patients who do not have an early virologic response does not increase sustained virologic response rates.59 Ribavirin should not be administered with zidovudine, because of the risk of anemia,60 or with didanosine, because of the risk of mitochondrial toxicity,61 so antiretroviral therapy may need to be modified before anti-HCV therapy is administered.

Despite these advances in the management of HCV infection in patients with HIV infection, many questions remain, such as the response to therapy in patients with very low CD4 cell counts and the optimal duration of therapy for each HCV genotype.56 Furthermore, the effects of moderate alcohol use and ongoing substance abuse on sustained virologic response rates are unknown.

In addition to the problem of treatment failures, many patients with HIV and HCV coinfection are not deemed to be candidates for current therapy because of one or more coexisting medical or psychiatric conditions.62,63 For patients in whom therapy has failed, clinical trials are currently examining whether the long-term administration of interferon might prevent the progression of fibrosis even in the absence of a virologic cure.55 New agents with specific activity against HCV are being tested, although none have been tested in patients with HIV and HCV coinfection. Two major targets of drug development are the serine protease (nonstructural protein 3) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (nonstructural protein 5B) proteins. Early phase 2 studies with one protease inhibitor, VX-950, showed marked early declines in HCV viral loads during treatment.64 However, future studies need to define the interaction of these agents with antiretroviral therapeutic agents and with each other.65,66 Finally, the benefit of liver transplantation in patients with HIV infection is being evaluated, and patients with end-stage liver disease can be referred for evaluation to centers with expertise in HIV infection and transplantation.49,67

HBV INFECTION

As with HCV infection, HBV infection in HIV-infected patients increases the risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and death from liver disease, especially in patients with a low CD4 cell count or concomitant alcohol use.68 As compared with patients who have HBV infection alone, patients with HBV and HIV coinfection have higher rates of chronic HBV infection and higher HBV DNA levels.10,14 Serum aminotransferase levels are less useful in assessing the need for therapy, since they may be lower in patients with HIV and HBV coinfection. In immunocompetent patients without HIV infection who are older than 30 years of age, the level of HBV DNA correlates with the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.69,70 However, such studies have not been performed in patients with coinfection. HBV has eight genotypes (A through H) with wide geographic distribution. Genotypes B and C are most common in Asia, and genotype A, which is more responsive to interferon therapy than are the other genotypes,71 is most common in Europe. The role of HBV genotypes in the natural history of the infection and in the response to therapy in patients with HIV coinfection is unclear. Monitoring of patients with HBV infection is critical because of the variable nature of the disease (Table 1).

One controversial issue has been the clinical relevance of an isolated positive test for antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc). In HIV-positive patients, a variable fraction of persons (10 to 45%) with an isolated positive test for anti-HBc have detectable levels of HBV DNA, or so-called occult HBV infection.72–76 Such atypical serologic findings have led to the recommendation that all patients with HIV infection undergo testing for HBsAg, antibodies against HBsAg (anti-HBs), and anti-HBc. If the tests for HBsAg, anti-Hbc, or both are positive, these patients should be tested for HBV DNA, since therapy for both HIV and HBV infection may be needed (Table 1). Patients without HBV DNA in serum (i.e., those who have anti-HBc alone) should be vaccinated against HBV and may — like HIV-negative patients — have a primary or anamnestic response.77,78

TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH HIV AND HBV COINFECTION

The treatment end points for HBV infection in HIV-infected patients are the suppression of viral replication (the absence of HBV DNA or hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg] in serum) and improvement in liver disease. Given the relatively low toxicity of many of the available therapeutic agents, a liver biopsy may not be needed for the assessment of risks and benefits in individual patients with elevated HBV DNA levels, although it may still offer important prognostic information. Immune control, as indicated by the loss of HBeAg and HBsAg or seroconversion to anti-HBe and anti-HBs, is rare in patients with HIV infection. Therefore, long-term therapy is the rule. Treatment guidelines for HBV infection in patients with HIV coinfection can be based on standard criteria if the HIV infection does not require therapy (Table 3).79,80 However, more research is needed to define the optimal strategy for the management of HBV infection in patients with HIV infection. Options for the management of HIV and HBV coinfection include interferons and nucleoside and nucleotide agents (Tables 2 and 3).80 Although pegylated interferon alfa is effective in both controlling HBV replication and reducing liver injury in patients with HBV monoinfection,81,82 it has not been tested in clinical trials of patients with HIV and HBV coinfection, and it is most successful in patients with high alanine aminotransferase levels and low HBV viral loads, both of which are uncommon in HIV infection.

Table 3.

Treatment Guidelines for HBV Infection in HIV-Negative Patients.*

| HBeAg Status | HBV DNA (IU/ml)† |

Alanine Aminotransferase |

Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | <20,000 | Normal | Monitor every 6–12 mo Consider liver biopsy; treat if fibrosis and inflammation present |

| Positive | ≥20,000 | Normal | Consider liver biopsy; if fibrosis present, treat with adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, or pegylated interferon |

| Positive | ≥20,000 | Elevated | Treat with adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, or pegylated interferon |

| Negative | <2,000 | Normal | Monitor every 6–12 mo |

| Negative | ≥2,000 | Normal | Consider liver biopsy; if fibrosis present, treat with adefovir, entecavir, or pegylated interferon |

| Negative | ≥2,000 | Elevated | Treat with adefovir, entecavir, or pegylated interferon |

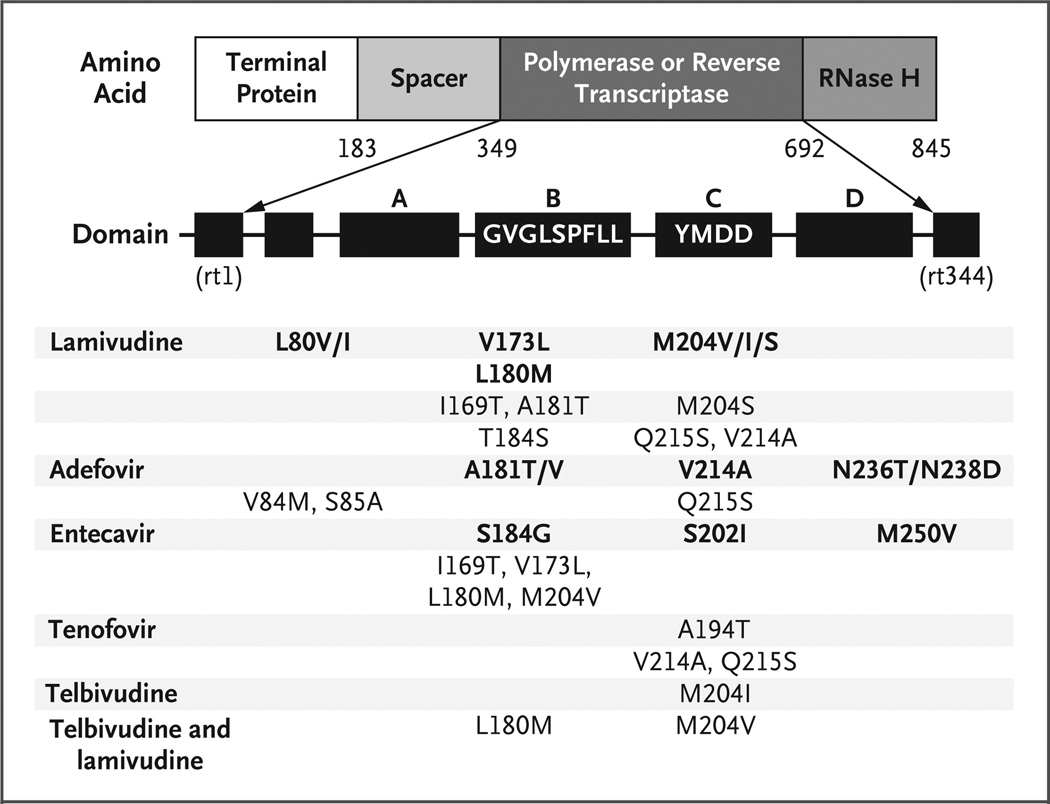

Nucleoside and nucleotide analogues approved for the treatment of HBV infection in the United States include lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, and telbivudine; tenofovir is not approved for HBV infection, although it has in vitro and in vivo activity against HBV.83–85 All of these agents target the HBV DNA polymerase.86 The use of lamivudine as the sole agent with anti-HBV activity is associated with unacceptably high rates of resistance (approaching 20 to 25% per year and 90% after 4 years).87 The first lamivudine-resistance mutation to be described was the YMDD mutation in domain C (Fig. 2). A lower rate of resistance to adefovir dipivoxil has been reported among patients without HIV infection, but the rate increases with time (18% at 4 years) among those receiving monotherapy.88 A randomized, controlled study comparing tenofovir and adefovir showed that both are safe and efficacious in decreasing HBV DNA levels in patients with coinfection. However, the majority of patients (96%) were also receiving lamivudine as part of antiretroviral therapy.83–85 Resistance to entecavir occurs in patients with a preexisting YMDD mutation, and resistance to wild-type HBV has not yet been seen. There has been one report of resistance to tenofovir in a patient with HBV infection.89 In patients without HIV infection, telbivudine is associated with a 61% rate of viral suppression (undetectable HBV DNA) and a 5% rate of resistance after 1 year of therapy.90 However, telbivudine shares cross-resistance with lamivudine and is therefore unlikely to be useful in patients who have received antiretroviral therapy.

Figure 2. HBV Reverse-Transcriptase and Polymerase Mutations That Confer Resistance to HBV Therapies.

The mutations are numbered according to the amino acid position in the polymerase and reverse transcriptase. The arrows denote the expansion of the polymerase or reverse transcriptase and show its various domains. The first nucleoside, rt1, corresponds to amino acid 349, and the last nucleoside, rt344, corresponds to amino acid 692. Patients who receive entecavir must have existing resistance to lamivudine. Tenofovir has not been approved for the treatment of HBV infection.

The likelihood of HBV resistance to nucleoside analogues is inversely proportional to the degree of the initial suppression of HBV. For example, the greater the degree of suppression with a nucleoside or nucleotide after 12 or 24 weeks of therapy, the lower the incidence of resistance.90,91 Recent guidelines from the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and other expert panels recommend that all patients who have HIV and HBV coinfection receive two active HBV drugs when HIV or both viruses require treatment,92,93 even though there are limited data on combination therapy in patients with either HBV monoinfection or HBV and HIV coinfection. A pilot study involving 35 patients with HIV and HBV coinfection who received adefovir and lamivudine for 4 years has not shown evidence of resistance, although most patients had YMDD mutations at baseline.94 The DHHS expert panel recommended tenofovir and emtricitabine (or lamivudine) as the preferred agents, although the Food and Drug Administration has not approved tenofovir for the management of HBV infection.

Patients who need treatment for HBV infection but not HIV infection should not receive HBV medications that have activity against HIV. Instead, they should receive agents with HBV activity alone; these agents include entecavir, interferon, and adefovir at a dose of 10 mg per day (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Some experts caution against the use of adefovir alone at a dose of 10 mg, since there is a theoretical risk of HIV resistance, but resistance has not been shown in vivo.89 Entecavir has not been evaluated in patients with HIV and HBV coinfection who are not receiving effective treatment for HIV at the same time. There is one reported case of resistance to HIV in a patient who was receiving entecavir without antiretroviral therapy.95 Lamivudine-resistant HBV infection may progress more slowly than untreated HBV infection, and continued therapy with the addition of another nucleotide is prudent in patients who already have lamivudine resistance.96 When changing or initiating antiretroviral regimens, it is important to continue administering agents with anti-HBV activity, since there is a risk of the immune reconstitution syndrome during recovery of CD4 cell counts; this syndrome may be difficult to distinguish from hepatotoxicity.

An important area for future research is the long-term efficacy of combination regimens in patients with HIV monoinfection and in those with HBV and HIV coinfection. For example, one recent study showed that adding tenofovir to a regimen in patients with lamivudine resistance resulted in nearly the same degree of viral suppression as an initial regimen of tenofovir and lamivudine in patients with wild-type HBV infection.97 The use of HBV agents in resource-limited settings depends on the availability of antiretroviral therapy and HBV drugs as well as the urgency associated with the treatment of life-threatening HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–defining complications.

FUTURE TREATMENTS FOR HEPATITIS

Future research will focus on small-molecule inhibitors, with and without pegylated interferon alfa, for the treatment of HCV infection and ideal combination therapies for HBV infection. Monitoring of patients for end-stage liver disease is a major focus of care and may lead to new opportunities for liver transplantation in patients with HIV infection.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (UO1 AI27663, to Dr. Peters, and AI27659, to Dr. Koziel).

Dr. Koziel reports receiving consulting or lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and Valeant and grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Valeant. Dr. Peters reports receiving consulting or lecture fees from Gilead, Idenix, and F. Hoffmann–La Roche and grant support from Achillion Pharmaceuticals and serving on an independent data monitoring committee for GlaxoSmithKline.

We thank Stephen Locarnini and Howard Libman for their assistance during the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Moller N, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: the D:A:D study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1632–1641. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmon-Ceron D, Lewden C, Morlat P, et al. Liver disease as a major cause of death among HIV infected patients: role of hepatitis C and B viruses and alcohol. J Hepatol. 2005;42:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benhamou Y. Antiretroviral therapy and HIV/hepatitis B virus coinfection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S98–S103. doi: 10.1086/381451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pol S, Lebray P, Vallet-Pichard A. HIV infection and hepatic enzyme abnormalities: intricacies of the pathogenic mechanisms. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S65–S72. doi: 10.1086/381499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powderly WG. Antiretroviral therapy in patients with hepatitis and HIV: weighing risks and benefits. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S109–S113. doi: 10.1086/381443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulkowski MS. Drug-induced liver injury associated with antiretroviral therapy that includes HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S90–S97. doi: 10.1086/381444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl):S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mast EE, Hwang LY, Seto DS, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the natural history of HCV infection acquired in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1880–1889. doi: 10.1086/497701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotz HM, van Doornum G, Niesters HG, den Hollander JG, Thio HB, de Zwart O. A cluster of acute hepatitis C virus infection among men who have sex with men — results from contact tracing and public health implications. AIDS. 2005;19:969–974. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171412.61360.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadler SC, Judson FN, O’Malley PM, et al. Outcome of hepatitis B virus infection in homosexual men and its relation to prior human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:454–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology. 2006;44:521–526. doi: 10.1002/hep.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goedert JJ, Brown DL, Hoots K, Sherman KE. Human immunodeficiency and hepatitis virus infections and their associated conditions and treatments among people with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2004;10(Suppl 4):205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon L, Flynn C, Muck K, Vertefeuille J. Prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C among entrants to Maryland correctional facilities. J Urban Health. 2004;81:25–37. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thio CL. Hepatitis B in the human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient: epidemiology, natural history, and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:125–136. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uneke CJ, Ogbu O, Inyama PU, Anyanwu GI, Njoku MO, Idoko JH. Prevalence of hepatitis-B surface antigen among blood donors and human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Jos, Nigeria. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:13–16. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vento S, Garofano T, Renzini C, et al. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:286–290. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellerman SE, Hanson DL, McNaghten AD, Fleming PL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B and incidence of acute hepatitis B infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:571–577. doi: 10.1086/377135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overton ET, Sungkanuparph S, Powderly WG, Seyfried W, Groger RK, Aberg JA. Undetectable plasma HIV RNA load predicts success after hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1045–1048. doi: 10.1086/433180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shire NJ, Welge JA, Sherman KE. Efficacy of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine in HIV-infected patients: a hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2006;24:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurence JC. Hepatitis A and B immunizations of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 10A):75S–83S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimland D, Guest JL. Response to hepatitis A vaccine in HIV patients in the HAART era. AIDS. 2005;19:1702–1704. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000186815.99993.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornejo-Juarez P, Volkow-Fernandez P, Escobedo-Lopez K, Vilar-Compte D, Ruiz-Palacios G, Soto-Ramirez LE. Randomized controlled trial of hepatitis B virus vaccine in HIV-1-infected patients comparing two different doses. AIDS Res Ther. 2006;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasricha N, Datta U, Chawla Y, et al. Immune responses in patients with HIV infection after vaccination with recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, et al. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562–569. doi: 10.1086/321909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merchante N, Giron-Gonzalez JA, Gonzalez-Serrano M, et al. Survival and prognostic factors of HIV-infected patients with HCV-related end-stage liver disease. AIDS. 2006;20:49–57. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198087.47454.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pineda JA, Macias J. Progression of liver fibrosis in patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus undergoing antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:417–419. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qurishi N, Kreuzberg C, Luchters G, et al. Effect of antiretroviral therapy on liver-related mortality in patients with HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection. Lancet. 2003;362:1708–1713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherner M, Letendre S, Heaton RK, et al. Hepatitis C augments cognitive deficits associated with HIV infection and methamphetamine. Neurology. 2005;64:1343–1347. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158328.26897.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Libman H, Saitz R, Nunes D, et al. Hepatitis C infection is associated with depressive symptoms in HIV-infected adults with alcohol problems. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1804–1810. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming CA, Christiansen D, Nunes D, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with HIV disease: impact of hepatitis C coinfection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:572–578. doi: 10.1086/381263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butt AA, Fultz SL, Kwoh CK, Kelley D, Skanderson M, Justice AC. Risk of diabetes in HIV infected veterans pre- and post-HAART and the role of HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2004;40:115–119. doi: 10.1002/hep.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus genetic variability: pathogenic and clinical implications. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:45–66. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greub G, Ledergerber B, Battegay M, et al. Clinical progression, survival, and immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Lancet. 2000;356:1800–1805. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03232-3. [Erratum, Lancet 2001; 357:1536.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller MF, Haley C, Koziel MJ, Rowley CF. Impact of hepatitis C virus on immune restoration in HIV-infected patients who start highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:713–720. doi: 10.1086/432618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan PS, Hanson DL, Teshale EH, Wotring LL, Brooks JT. Effect of hepatitis C infection on progression of HIV disease and early response to initial antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20:1171–1179. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226958.87471.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nunez M. Hepatotoxicity of antiretrovirals: incidence, mechanisms and management. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 1):S132–S139. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braitstein P, Justice A, Bangsberg DR, et al. Hepatitis C coinfection is independently associated with decreased adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a population-based HIV cohort. AIDS. 2006;20:323–331. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198091.70325.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hooshyar D, Napravnik S, Miller WC, Eron JJ., Jr Effect of hepatitis C coinfection on discontinuation and modification of initial HAART in primary HIV care. AIDS. 2006;20:575–583. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210612.37589.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aranzabal L, Casado JL, Moya J, et al. Influence of liver fibrosis on highly active antiretroviral therapy-associated hepatotoxicity in patients with HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:588–593. doi: 10.1086/427216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghany MG, Kleiner DE, Alter H, et al. Progression of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:97–104. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pawlotsky JM. Virology of hepatitis B and C viruses and antiviral targets. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 1):S10–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goedert JJ, Hatzakis A, Sherman KE, Eyster ME. Lack of association of hepatitis C virus load and genotype with risk of end-stage liver disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1202–1205. doi: 10.1086/323665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanchez-Conde M, Berenguer J, Miralles P, et al. Liver biopsy findings for HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C and persistently normal levels of alanine aminotransferase. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:640–644. doi: 10.1086/506440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marks KM, Petrovic LM, Talal AH, Murray MP, Gulick RM, Glesby MJ. Histological findings and clinical characteristics associated with hepatic steatosis in patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1943–1949. doi: 10.1086/497608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sulkowski MS, Mehta SH, Torbenson M, et al. Hepatic steatosis and antiretroviral drug use among adults coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus. AIDS. 2005;19:585–592. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163935.99401.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelleher TB, Afdhal N. Assessment of liver fibrosis in co-infected patients. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 1):S126–S131. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Ledinghen V, Douvin C, Kettaneh A, et al. Diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis by transient elastography in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:175–179. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194238.15831.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004;39:841–856. doi: 10.1002/hep.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roland ME, Stock PG. Liver transplantation in HIV-infected recipients. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:273–284. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lau DT, Kleiner DE, Ghany MG, Park Y, Schmid P, Hoofnagle JH. 10-Year follow-up after interferon-alpha therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1998;28:1121–1127. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, et al. Impact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1303–1313. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carrat F, Bani-Sadr F, Pol S, et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b vs standard interferon alfa-2b, plus ribavirin, for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-infected patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:2839–2848. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung RT, Andersen J, Volberding P, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:451–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laguno M, Murillas J, Blanco JL, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for treatment of HIV/HCV co-infected patients. AIDS. 2004;18:F27–F36. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200409030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Torriani FJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rockstroh JK, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:438–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moreno A, Barcena R, Garcia-Garzon S, et al. HCV clearance and treatment outcome in genotype 1 HCV-monoinfected, HIV-coinfected and liver transplanted patients on peg-IFN-alpha-2b/ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2005;43:783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fuster D, Planas R, Gonzalez J, et al. Results of a study of prolonging treatment with pegylated interferon-alpha2a plus ribavirin in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients with no early virological response. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:473–482. [Erratum, Antivir Ther 2006; 11:667.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alvarez D, Dieterich DT, Brau N, Moorehead L, Ball L, Sulkowski MS. Zidovudine use but not weight-based ribavirin dosing impacts anaemia during HCV treatment in HIV-infected persons. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:683–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bani-Sadr F, Carrat F, Pol S, et al. Risk factors for symptomatic mitochondrial toxicity in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients during interferon plus ribavirin-based therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174649.51084.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nunes D, Saitz R, Libman H, Cheng DM, Vidaver J, Samet JH. Barriers to treatment of hepatitis C in HIV/HCV-coinfected adults with alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1520–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thompson VV, Ragland KE, Hall CS, Morgan M, Bangsberg DR. Provider assessment of eligibility for hepatitis C treatment in HIV-infected homeless and marginally housed persons. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 3):S208–S214. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192091.38883.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reesink HW, Zeuzem S, Weegink CJ, et al. Rapid decline of viral RNA in hepatitis C patients treated with VX-950: a phase Ib, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:997–1002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coelmont L, Paeshuyse J, Windisch MP, De Clercq E, Bartenschlager R, Neyts J. Ribavirin antagonizes the in vitro antihepatitis C virus activity of 2’-C-methylcytidine, the active component of valopicitabine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3444–3446. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00372-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koev G, Dekhtyar T, Han L, et al. Antiviral interactions of an HCV polymerase inhibitor with an HCV protease inhibitor or interferon in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2007;73:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miro JM, Laguno M, Moreno A, Rimola A. Management of end stage liver disease (ESLD): what is the current role of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT)? J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 1):S140–S145. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thio CL, Seaberg EC, Skolasky R, Jr, et al. HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and risk of liver-related mortality in the Multicenter Cohort Study (MACS) Lancet. 2002;360:1921–1926. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678–686. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fung SK, Lok AS. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: do they play a role in the outcome of HBV infection? Hepatology. 2004;40:790–792. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hofer M, Joller-Jemelka HI, Grob PJ, Luthy R, Opravil M. Frequent chronic hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-infected patients positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen only. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:6–13. doi: 10.1007/BF01584356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Piroth L, Binquet C, Vergne M, et al. The evolution of hepatitis B virus serological patterns and the clinical relevance of isolated antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen in HIV infected patients. J Hepatol. 2002;36:681–686. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pogany K, Zaaijer HL, Prins JM, Wit FW, Lange JM, Beld MG. Occult hepatitis B virus infection before and 1 year after start of HAART in HIV type 1-positive patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:922–926. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santos EA, Yoshida CF, Rolla VC, et al. Frequent occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:92–98. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shire NJ, Rouster SD, Rajicic N, Sherman KE. Occult hepatitis B in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:869–875. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gandhi RT, Wurcel A, Lee H, et al. Response to hepatitis B vaccine in HIV-1-positive subjects who test positive for isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen: implications for hepatitis B vaccine strategies. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1435–1441. doi: 10.1086/429302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McMahon BJ, Parkinson AJ, Helminiak C, et al. Response to hepatitis B vaccine of persons positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:590–594. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90851-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:936–962. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857–861. doi: 10.1002/hep.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lada O, Benhamou Y, Cahour A, Katlama C, Poynard T, Thibault V. In vitro susceptibility of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus to adefovir and tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peters MG, Andersen J, Lynch P, et al. Randomized controlled study of tenofovir and adefovir in chronic hepatitis B virus and HIV infection: ACTG A5127. Hepatology. 2006;44:1110–1116. doi: 10.1002/hep.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Bommel F, Wunsche T, Mauss S, et al. Comparison of adefovir and tenofovir in the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;40:1421–1425. doi: 10.1002/hep.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Locarnini S. Molecular virology of hepatitis B virus. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24(Suppl 1):3–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Thibault V, et al. Long-term incidence of hepatitis B virus resistance to lamivudine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Hepatology. 1999;30:1302–1306. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Angus P, Vaughan R, Xiong S, et al. Resistance to adefovir dipivoxil therapy associated with the selection of a novel mutation in the HBV polymerase. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:292–297. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00939-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sheldon J, Camino N, Rodes B, et al. Selection of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations in HIV-coinfected patients treated with tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:727–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lai CL, Leung N, Teo EK, et al. A 1-year trial of telbivudine, lamivudine, and the combination in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yuen MF, Sablon E, Hui CK, Yuan HJ, Decraemer H, Lai CL. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology. 2001;34:785–791. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. [Accessed March 16, 2007]. DHHS guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Benhamou Y. Treatment algorithm for chronic hepatitis B in HIV-infected patients. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 1):S90–S94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Benhamou Y, Thibault V, Vig P, et al. Safety and efficacy of adefovir dipivoxil in patients infected with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B and HIV-1. J Hepatol. 2006;44:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Important information regarding BARACLUDE®(entecavir) in patients coinfected with HIV and HBV. [Accessed March 16, 2007]; at http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007/baraclude_dhcp_02-2007.pdf.

- 96.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schmutz G, Nelson M, Lutz T, et al. Combination of tenofovir and lamivudine versus tenofovir after lamivudine failure for therapy of hepatitis B in HIV-coinfection. AIDS. 2006;20:1951–1954. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247116.89455.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]