Abstract

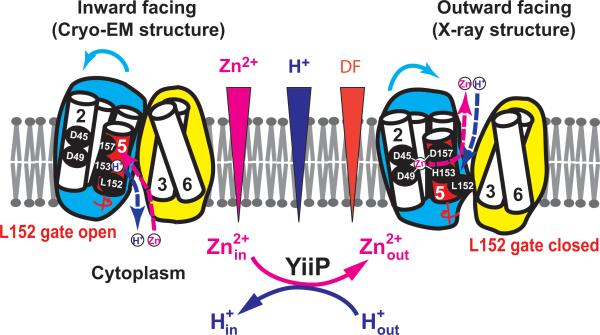

The proton gradient is a principal energy source for respiration-dependent active transport, but the structural mechanisms of proton-coupled transport processes are poorly understood. YiiP is a proton-coupled zinc transporter found in the cytoplasmic membrane of E. coli, and the transport-site of YiiP receives protons from water molecules that gain access to its hydrophobic environment and transduces the energy of an inward proton gradient to drive Zn(II) efflux1,2. This membrane protein is a well characterized member3-7 of the protein family of cation diffusion facilitators (CDFs) that occurs at all phylogenetic levels8-10. X-ray mediated hydroxyl radical labeling of YiiP and mass spectrometric analysis showed that Zn(II) binding triggered a highly localized, all-or-none change of water accessibility to the transport-site and an adjacent hydrophobic gate. Millisecond time-resolved dynamics revealed a concerted and reciprocal pattern of accessibility changes along a transmembrane helix, suggesting a rigid-body helical reorientation linked to Zn(II) binding that triggers the closing of the hydrophobic gate. The gated water access to the transport-site enables a stationary proton gradient to facilitate the conversion of zinc binding energy to the kinetic power stroke of a vectorial zinc transport. The kinetic details provide energetic insights into a proton-coupled active transport reaction.

Mammalian homologs of YiiP are responsible for zinc sequestration into secretory vesicles, thus playing important roles in neurotransmission11 and hormone secretion12. Zinc efflux catalyzed by YiiP is coupled with proton influx in a 1:1 zinc-for-proton exchange stoichiometry3. When protons are scarce at higher pH, zinc transport comes to a halt despite a large zinc concentration gradient7. Thus, the zinc-for-proton coupling is obligatory. Biochemical studies and x-ray structures of YiiP showed that zinc transport is mediated by a tetrahedral Zn(II) binding site in the center of the transmembrane domain (TMD)1,4. This intramembranous zinc transport-site adopts coordination geometry satisfied by three Asp and one His residues, but lacks any additional polar or charged residues in the Zn(II) binding pocket. The absence of available pH titratable residues in the second coordination sphere necessitates water access to fulfill proton donor or acceptor functions to enable the obligatory zinc-for-proton exchange. However, the crystal structure of zinc-bound YiiP (zinc-YiiP) shows that water access to the transport-site is blocked by hydrophobic residues that divide the zinc translocation pathway into an extracellular and intracellular cavity13. A protein conformational change is expected to open up a water portal within the hydrophobic seal. As water molecules gain access to the transport-site in a transport reaction cycle, irradiating YiiP to a millisecond synchrotron x-ray pulse could render residues in contact with waters susceptible to hydroxyl radical mediated oxidative modification, thereby permitting the monitoring of residues motions in terms of water accessibility change14,15. Radiolytic hydroxyl radicals under such experimental conditions are generated rapidly and isotropically in both bulk and activated bound waters with sidechain oxidation completed within milliseconds15-18. By comparison, the macroscopic timescale for zinc transport is in the order of 200-500 milliseconds3,7. Thus, time-resolved hydroxyl radical “footprinting” would have a sufficient time resolution to monitor proton translocation and associated protein conformational change.

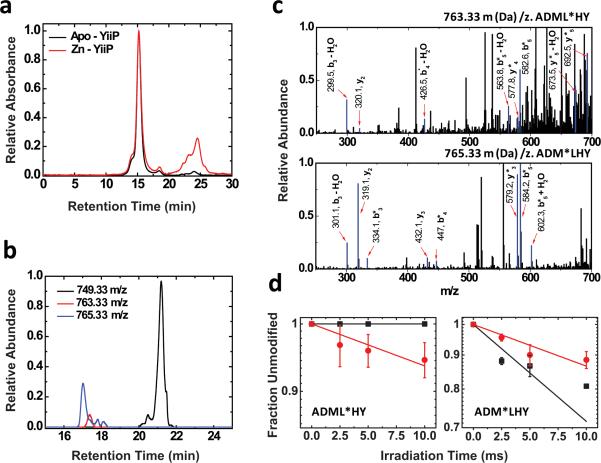

Purified YiiP in detergent micelles was exposed to a focused synchrotron white beam, followed by a rapid mix with methionine-amide to quench secondary radical chain reactions (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The effective hydroxyl radical concentration was controlled in the μM range as indicated by an Alexa 488 dosimeter, and secondary radiation damage of YiiP was minimized by adjusting the x-ray irradiation to an optimal dose range14,16. As a result, only negligible differences in size-exclusion HPLC profiles were observed for the protein peaks before and after X-ray irradiation (Fig. 1a). The broad low molecular peak in zinc-YiiP (red trace) corresponded to the methionine-amide quencher added to the apo-YiiP sample after irradiation. The sites of oxidative modification were characterized by +14, +16 and +32 Da oxygen-based mass adducts14,15,18, which were detected by bottom-up liquid chromatography (LC)-mass spectrometry (MS) of proteolytic fragments of the irradiated YiiP (Fig. 1b), and confirmed by MS/MS assignments (Fig. 1c). The overall mass spectrometric sequence coverage was 82% (Extended Data Fig. 2a), encompassing all residues located within the inter-cavity seal (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Increasing x-ray irradiation progressively increased the modified and reduced the unmodified populations, giving rise to a dose-response plot for each modified site (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3). The initial phase of the dose plot followed a pseudo first-order reaction, but occasional deviations from the exponential function were observed at increased irradiation times as a result of secondary modifications (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3). Therefore, the slope of the initial phase was used to quantify the hydroxyl radical reactivity (Extended Data Table 1).

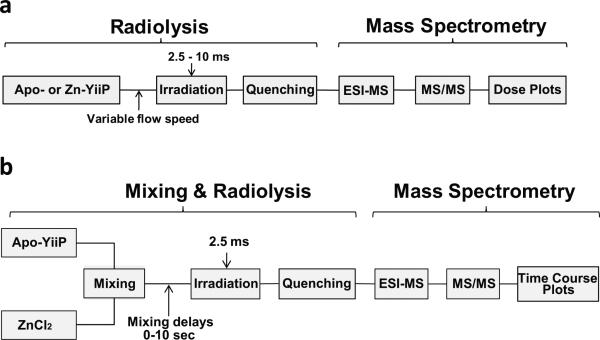

Extended Data Figure 1. Steady state and time resolved synchrotron X-ray radiolysis.

Experimental scheme for obtaining steady state dose plots. b: Experimental schemes for obtaining the time course of water accessibility change.

Fig. 1. Radiolytic labeling and mass spectrometric analysis.

a: Size-exclusion HPLC chromatograms of apo-YiiP before irradiation and zinc-YiiP after irradiation. b: Examples for quantification of radiolytic labeling by LC-MS; extracted ion-count chromatograms of singly protonated, unmodified (749.33 m/z Da, black), carbonylated (+14 Da mass shift, 763.33 m/z, red) and hydroxylated (+ 16 Da mass sift, 765.33 m/z , blue) peptide ADMLHY. c: Examples for identification of modified residues by tandem mass spectrometry of the cabonylated and hydroxylated ADMLHY with peak assignments (red arrow and blue line) confirming L152 and M151 modification, respectively. d: Does-responses showing reciprocal solvent accessibility changes at L152 and M151 sites in apo-YiiP (red) and zinc-YiiP (black). Solid lines represent least-squares fits of the means of dose dependent data and the error bar represents standard error from 4-6 independent measurements.

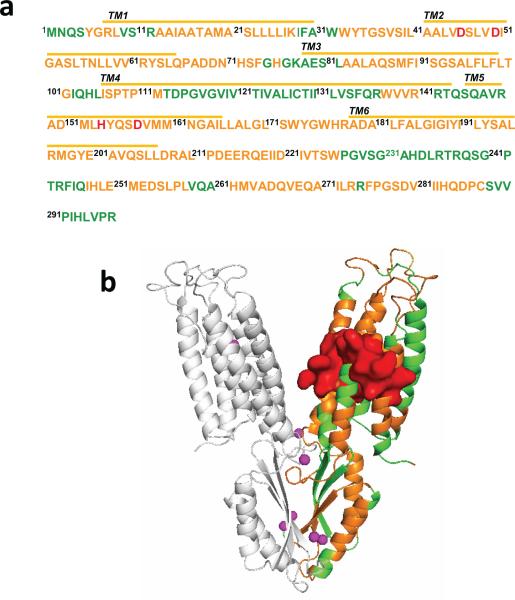

Extended Data Figure 2. a. Mass spectrometry sequence coverage.

The detectable peptides, undetectable residues and coordination residues of the transport-site are shown in orange, green and red respectively. Transmembrane helixes (TMs) are underlined as indicated. b: Mapping detectable proteolytic peptides to the YiiP crystal structure. Detectable and undetectable peptides in one protomer of a YiiP homodimer are colored in orange and green, respectively. The sidechains of detectable residues located between two cavities are shown in surface representation and colored in red. Bound zinc ions are shown as magenta spheres.

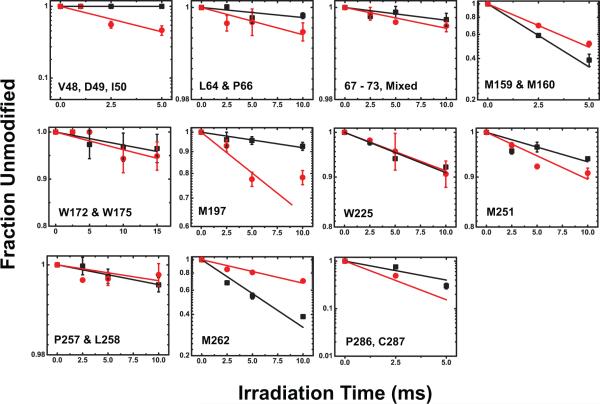

Extended Data Figure 3. Does-responses for modified sites in apo-YiiP (red) and zinc-YiiP (black).

Solid lines represent least-squares fits of the dose dependent data as described in Methods. The reactivity rate for each site as indicated is summarized in Extended Data Table 1. Note, the linear does-response on a logarithm scale indicates negligible radiation damage by 10 ms irradiation to all sites except M151, M197 and P286C287 which reached saturation at 5 ms. In these cases, the 10 ms data points were not used in linear regression. Dose response plots for M151 and L152 is shown in Fig 1d. Zinc binding to a solvent exposed zinc site located on the cytoplasmic membrane surface (Z2, Fig. 2b) yielded 38-67% reductions in oxidative modification of neighboring L64, P66, D68, D69, H71 and F73 within the peptide SLQPADDNHSF (Extended Data Table 1). A marginal 20% reduction in water accessibility change by zinc binding was also localized to W172 and W175 within an extracellular loop connecting TM5 and TM6 (Fig. 2b). This loop is disordered in the crystal structure. Structural flexibility likely allows for distinct loop conformations in response to zinc binding. A total of six modified sites were identified in CTD (Extended Data Table 1). Two sites (M251, P286/C287) with reduced water accessibility for zinc-YiiP are located near the binuclear zinc binding site at the CDT-CDT interface. Zinc binding may partially protect these sites from labeling, but the protection was incomplete because of the solvent exposure. Two sites on the CTD protein surface (W225, P257/L258) showed no detectable change as expected for fully exposed residues. Still two more sites exhibited an increase in water accessibility for zinc-YiiP. The first site (D207-L210) was mapped to a TMD-CDT linker which is involved in a hinge-like conformational change in response to zinc binding1. The second site involved M262 on the CDT surface. There was no obvious explanation for the increase of water accessibility to this methionine residue.

| Seq No.a | Sequenceb | Modified residues and observed mass shifts c | k s-1 Zinc-Yiipd | k s-1 Apo-YiiP | Ratio (R)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-8 | YGRL | -f | - | - | - |

| 15-27 | AATAMASLLLLIK | - | - | - | - |

| 32-40 | WYTGSVSIL | - | - | - | - |

| 41-47 | AALVDSL | - | - | - | - |

| 47-50 | LVDI | V48.D49.I50 ( + 14 Da) | 0.05± 0.1 | 163.0 ± 25 | 3x10-4±±4x10-5 |

| 58-62 | LLWRY | - | - | - | - |

| 63-73 | SLOPADDNHSF | L64.P66 (+16 Da) | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0 1 | 0.37 ±0.2 |

| D68,D69,H71,F73(+16Da) | 0.3 ±0.06 | 0.5 ±0.06 | 0.62 ±0.2 | ||

| 82-88 | AALAQSM | - | - | - | - |

| 82-89 | AALAQSMF | - | - | - | - |

| 90-96 | ISGSALF | - | - | - | - |

| 97-101 | LFLTG | - | - | - | - |

| 106-111 | ISPTPM | - | - | - | - |

| 137-140 | WWR | - | - | - | - |

| 149-154 | ADMLHY | M151 ( + 16 Da) | 35.5 + 6.0 | 14 4 ± 2 4 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| L152I + 14 Da) | 0.05 ±0.1 | 8.5±0.7 | 0 006 ±0.002 | ||

| 149-177 | ADMLHYQSDVMM NGAILLALGLSWYGWHRh | W172, W175(+32 Da) | 2.8 ±0.6 | 3.8 ±0.6 | 0.8 ±0.3 |

| 153-165 | VMMNGAIL | M159.M160 ( + 16 Da) | 213 ± 1.0 | 142±05 | 1.5 ±0.01 |

| 178-196 | ADALFALGIGIYILYSALR | - | - | - | - |

| 185-189 | GIGIY | - | - | - | - |

| 197-208 | MGYEAVQSLLDR | M197 ( + 16 Da) | 8.3 ±3.0 | 30.8 ±4.4 | 0.3 ±0.1 |

| 207-220 | DRALPDEERQEIID | 207-210 (+ 16) | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 2.0 | 1.6 ±1.0 |

| 209-225 | ALPDEERQEIIDIVTSWi | W225 (+32 Da) | 9.1 ±0.7 | 9.5 ±0.8 | 0.97 ±0.2 |

| 247-258 | IHLEMEDSLPL | M251 (+ 16 Da) | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ±1.5 | 0.65 ± 2 |

| P257.L258 ( + 14 Da) | 0.4 ±0.1 | 0.4 ±0.1 | 1 ± 0.5 | ||

| 262-272 | MVADOVEOAIL | M262(+ 16 Da) | 113 5 + 10 | 39.4 ±5.5 | 3 ±0.7 |

| 275-283 | FPGSDVIIH | - | - | - | - |

| 275-287 | RFPGSDVIIHQDPC | P286.C287 (+ 16 Da) | 184 ± 44 | 374 ± 80 | 0.54 ± 0.23 |

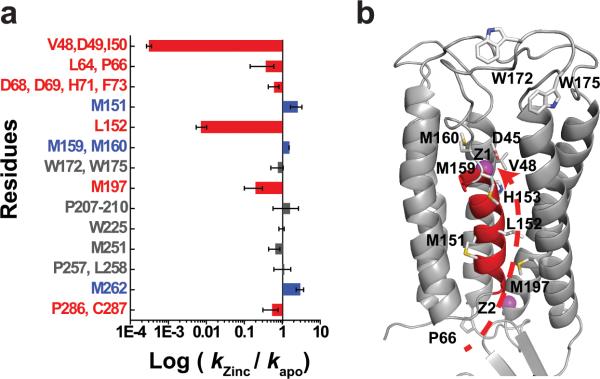

The rate of sidechain labeling is governed by intrinsic reactivity of the amino acid and water accessibility to the sidechain14,15. The ratio of the measured reactivity rates for the same residue from zinc-YiiP and apo-YiiP gave a ratiometric account of the water accessibility change independent of the intrinsic sidechain reactivity or sequence context. Among all the detectable sites of modification, two sites exhibited conspicuously large differences in reactivity in the presence and absence of zinc (Fig. 2a). One instance where Zn(II) binding reduced reactivity more than 1000-fold was observed for three consecutive residues, namely V48, D49 and I50 within the peptide LVDI of TM2 (Extended Data Table 1). In the crystal structure of zinc-YiiP (PDB ID 3H90), D49 binds Zn(II) in the transport-site and is one helical turn away from a structural water that is immobilized via a hydrogen bond to S53 (3.1 Å to Oγ) (Fig 3a).

Fig. 2. Quantification of water accessibility changes.

a: Water accessibility changes in response to Zn(II) binding measured by the ratio of labeling rates for residues with an increase (blue), decrease (red) or no change (grey) in water accessibility after a rapid Zn(II) exposure. The labeling rate for each site as indicated is summarized in Extended Data Table 1, and the error bar represents standard error from 4-6 independent measurements. b: Residues with a partial water accessibility change in response to zinc binding. TM5 is colored in red. Z1 and Z2 (magenta spheres) represent bound zinc ions. Arrow indicates a putative zinc transport pathway from the cytoplasm through the L152 gate to the transport-site.

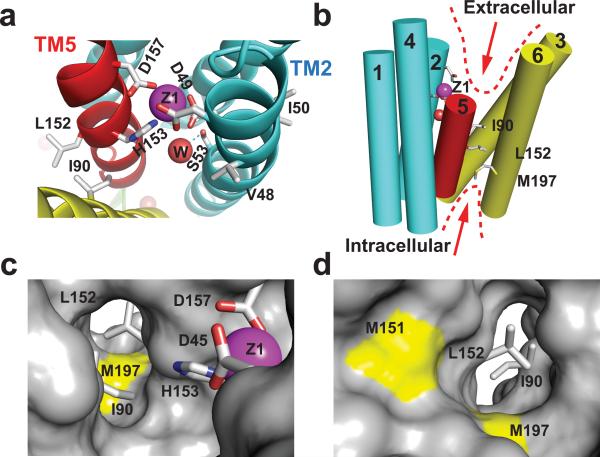

Fig. 3. L152 controls the opening of an inter-cavity water portal.

a: A structural water molecule (W, red sphere) near the transport-site occupied by a tetrahedral coordinated Zn(II) (Z1, magenta sphere), viewed from the periplasm. Relevant residues are drawn in sticks and labeled accordingly. TM5 is colored in red as indicated. b: Intracellular and extracellular cavity as outlined by dash lines. c: L152 gate viewed from the extracellular cavity along the arrow as indicated in b. The sidechains of L152, I90 and coordination residues in the transport-site (sticks) are excluded from the protein surface drawing. M197 is shown as a yellow patch at the cytoplasmic entrance to the inter-cavity portal. d: L152 gate viewed from the intracellular cavity along the arrow as indicated in b. M151 and M197 are visible as yellow patches on the protein surface.

Coordination of Zn(II) to the transport-site may suppress productive radiolysis of this structural water, resulting in a negligible rate of VDI labeling in zinc-YiiP (Extended Data Table 1). In sharp contrast, the absence of a coordinated Zn(II) in apo-YiiP permitted an unusually fast radiolytic labeling at 163 s−1 (Extended Data Table 1) . Such a high level of reactivity has been observed for radiolytic labeling by structural water molecules in the hydrophobic core of a G-protein coupled receptor17.

The second largest change was observed for a +14 Da modification of L152 in the peptide ADMLHY of TM5 (Fig. 2a). In apo-YiiP, the rate of +14 Da modification for L152 was 8.5 s−1 (Extended Data Table 1) while Zn(II) binding reduced the reactivity of L152 more than 100-fold, to a negligible level, illustrating that a Zn(II)-binding induced conformational change removed water access to the sidechain of L152. This peptide contained another labeled residue M151, whose +16 Da modified products could be isolated from those of L152 based on difference in the m/z ratio (Fig 1b and 1c). The same conformational change that reduced reactivity of L152 yielded a 2.5-fold increase in reactivity for the neighboring M151 (Fig. 1d and Fig. 2a). In the zinc-YiiP structure, L152 is fully buried and oriented toward the intracellular cavity as a part of the inter-cavity seal, consistent with the lack of radiolytic labeling (Fig. 3a).

L152 is located at the interface between a TM3-TM6 helix pair and a compact TM1-TM2-TM4-TM5 four-helix-bundle (Fig. 3b). These two subdomains cross over to form two cavities located on either side of the membrane as indicated by arrows in Fig. 3b. The inter-domain packing wedges TM5 (colored in red) at one corner of the four-helix-bundle into the TM3-TM6 interface with L152 situated at the center of the TM5→TM3-TM6 triple-helix joint (Fig. 3b). L152 interacts with I90 from TM3 and A194 from TM6 to form a tight knob-into-hole packing. The I90 equivalents have been identified as metal determinant residues in plant and yeast CDF homologs19,20. One helical turn down toward the intracellular cavity is another layer of residue triad: A83 from TM3, A149 from TM5 and M197 from TM6 that define the innermost section of the intracellular cavity (Fig. 3b). Of note, the conformational changes of M197 echo those of L152, with a zinc-dependent reduction of solvent accessibility (Fig. 2a) except that M197's accessibility is not reduced to the background level in the zinc-bound state (Extended Data Fig. 3). This cluster of six residues forms a highly conserved TM5→TM3-TM6 packing core (Extended Data Fig. 4) with L152 serving as a principal hydrophobic barrier between the two cavities (Fig. 3c-d). The structural and functional importance of L152 was examined by a series of point mutations (Extended Data Fig. 5). All L152 mutants expressed well. However, substitutions of L152 with smaller (G, A), bulky aromatic (F) and charged residues (D, R) resulted in complete denaturation after the mutant proteins were solubilized by DDM, whereas conserved L152 substitutions with I and M residues were partially tolerated (Extended Data Fig. 5). The sidechain dependent effects of L152 mutations on protein stability are consistent with a critical structural role for L152 in the highly conserved TM5→TM3-TM6 packing core.

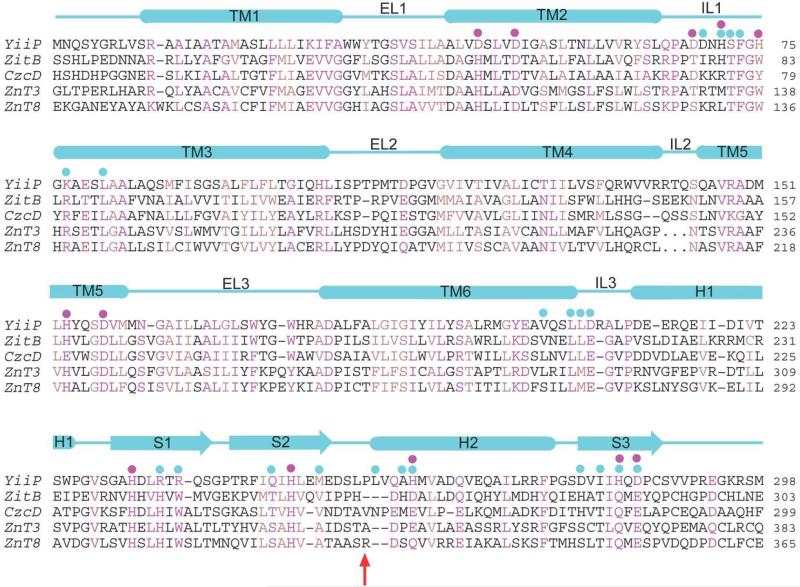

Extended Data Figure 4. Sequence conservation of the inter-cavity seal.

Residues involved in TM5→TM3-TM6 packing are marked by black asterisks in a CDF sequence alignment. Conserved and homologous residues are colored in magenta and light-blown. Magenta, cyan and black dots indicate residues involved in zinc coordination, dimerization contacts and the interlocked (Lys77-Asp207)2 salt-bridges, respectively. Dashed lines in two human ZnT sequences represent omitted residues in a loop (IL2) between TM4 and TM5. Red arrow indicates the position of the R325W mutation in human ZnT8.

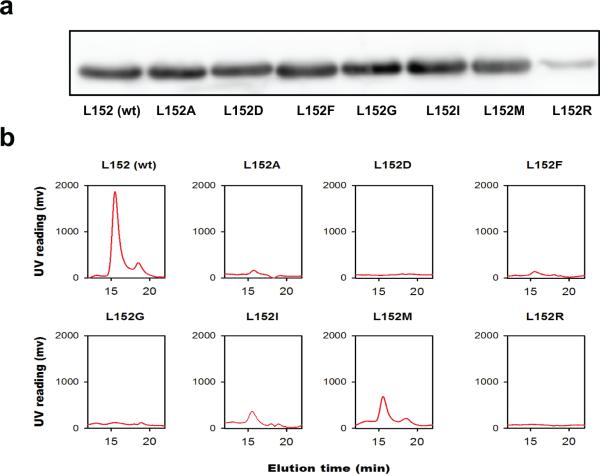

Extended Data Figure 5. Expression and size-exclusion analysis of purified L152 mutants.

L152 was substituted by an A, D, F, G, I, M or R residue to evaluate the effect of L152 mutations on structural stability. a: Western-blot analysis of the expression of YiiP and L152 mutants as indicated. Only a L152R point mutation caused a modest reduction of protein expression whereas other L152 substitutions and wild type YiiP showed a similar level of expression based on western-blot detection of His-tagged proteins in membrane vesicles using a monoclonal antibody against the poly-histidine tag. b: Eluted protein peaks for YiiP and L152 mutants as indicated after the removal of protein aggregates by ultracentrifugation. YiiP and L152 mutants were solubilized by DDM and purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography and size exclusion HPLC. The purified wild type YiiP remained stable in DDM micelles for weeks. Sizing HPLC analysis showed a monodisperse YiiP peak followed by a minor detergent peak eluted at expected retention times6. In sharp contrast, purified L152 mutants rapidly denatured, forming lager protein aggregates. After removing the aggregates by ultracentrifugation, none of the purified L152A, D, F, G, and R became detectable by sizing HPLC. Two conserved L152 substitutions, L152I and L152M showed a significantly reduced peak volume within 48 hours of DDM solubilization. A prolonged DDM solubilization led to complete denaturation of L152I and L152M while the wild type YiiP remained stable under the same experimental condition. Thus, L152 is critically important to the protein stability in detergent micelles. The lack of protein stability in detergent solution precluded functional reconstitution and characterization of purified L152 mutants.

Among all the detectable sites, only the transport-site and its neighboring L152 gate exhibited all-or-none water accessibility changes (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 3, and Fig. 2a), suggesting a tight control of water leakage across the membrane. Within the TMD, oxidative modifications were observed at four reactive Met residues outside of the transport-site and the L152 gate. As noted above, M197 at the intracellular entrance to the L152 gate (Fig. 2b) showed a 70% reduction in water accessibility upon Zn(II) binding (Fig. 2a) whereas M151, M159 and M160 at the N- and C-terminus of TM5 (Fig. 2b) showed a 50-130% increase of water accessibility (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Table 1). These latter Met residues reside on a helical face of TM5 with increased water accessibility upon Zn(II) binding (Fig. 2b). By contrast, residues with a reduction of water accessibility upon Zn(II) binding are either located on the opposite TM5 face (e.g. L152) or packed against the opposite TM5 face (V48 and M197) (Fig. 2b). The tetrahedral transport-site (H153, D157, D45 and D49) is also located on the same TM5 face with a zinc-dependent loss of water accessibility. The reciprocal change in water accessibility on two opposite TM5 faces is consistent with re-orientation of TM5 in response to Zn(II) binding. Furthermore, solvent accessible residues in apo-YiiP were found to line a putative transmembrane zinc pathway, starting from M197 in the intracellular cavity, through L152 within the inter-cavity seal and arriving at H153, V48 and D49 in the extracellular cavity (Fig. 2b). This finding of a well-defined channel from the transport-site in apo-YiiP to the intracellular cavity is in agreement with an inward-facing conformation revealed by an electron crystallographic structure of an apo-YiiP homolog21.

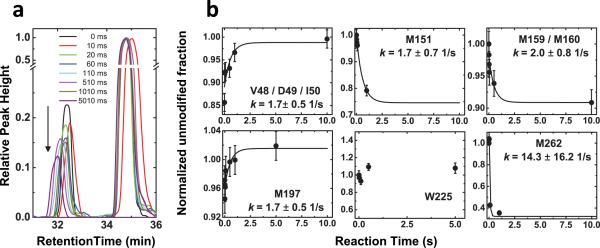

In order to understand the structural dynamics of the Zn-dependent closing of the inter-cavity portal, we monitored the time course of radiolytic modification upon rapid mixing of apo-YiiP and 0.2 mM ZnCl2(Extended Data Fig. 1b). Only highly reactive residues could be detected with a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio for quantitative kinetic analysis (Fig. 4a). In the TMD, time-resolved measurements were performed on four Met residues (M151, M159/M160 and M197) and the V48/D49/I50 peptide. After mixing of apo-YiiP and Zn(II), the exponential increases in unmodified V48/D49/I50 and M197 residues, indicative of the closing of the inter-cavity portal, mirrored the exponential falls in unmodified M151 and M159/M160 residues (Fig. 4b). The rates of reciprocal water accessibility changes for these four positions on opposite faces of TM5 were identical within experimental errors, suggesting that TM5 underwent a rigid-body re-orientation upon zinc binding. The rigid-body motion of TM5 predicted a similar rate of L152 motion. Averaging the rates of four detectable sites gave an overall rate of TM5 motion at 1.8 ± 0.7 s−1, approximating the macroscopic transport rate (2-5 s−1) determined by stopped-flow Zn(II) flux measurements3,7. Thus, zinc access to the transport-site and the ensuing TM5 motion linked to the closing of the L152 gate occurs on the same time scale. As an internal control, time-resolved measurement showed no changes in labeling to W225 on the CTD surface (Fig. 4b). Another surface residue M262, however, exhibited a rapid change at 14.3 s−1 (Fig. 4b). The marked kinetic difference suggested that the observed water accessibility change to M262 preceded TM5 motion, but its functional relevance is unclear.

Fig.4. Kinetics of water accessibility changes.

a: An example of extracted ion chromatograms from the unmodified and modified M197 in peptide 197-208. The data were smoothed by a low-passing filter and normalized to the peak height of respective unmodified species. The arrow indicates a progressive decrease of the modified peaks as a function of the reaction time. b: Time courses of water accessibility change for indicated residues. The solid line represents a single exponential fit of the time course of the unmodified fraction with a fitted rate constant (k) presented as mean ± standard error from six independent measurements.

The time-resolved data suggested that Zn(II) binding triggers a concerted rigid-body motion of TM5 that swings L152 into place to plug the inter-cavity seal (Fig. 5). Since the four coordination residues of the transport-site are projected from TM2 and TM5 (Fig. 3a), a TM5 motion is expected to alter the TM2-TM5 inter-helix orientation that determines the coordination geometry of the transport-site1. Thus, a rigid-body TM5 motion would simultaneously affect the mode of Zn(II) coordination and the gating of the inter-cavity portal through L152 movement (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 3c-d, the opening of the L152 gate would expose the transport-site through a nanotube to the aqueous bulk of the intracellular cavity22. When a Zn(II) from the intracellular cavity reaches the transport-site, the favorable match of its coordination chemistry with the tetrahedral transport-site23 would release binding free energy in the confinement of the hydrophobic core where the free energy may be guided to trigger TM5 reorientation. By analogy to the working of a combustion engine, the released zinc binding energy is transformed to useful mechanical energy, providing the power stroke of TM5 reorientation to close the L152 gate (Fig. 5). As a result, this conformational change alternatively exposes the transport-site to intracellular and extracellular cavity. The in vivo transmembrane proton gradient of an enteric bacterium E. coli is about one to two pH units24. The flipping of H153 as a part of the transport-site to either side of the membrane with a physiological pH gradient is expected to change its protonation state. A deprotonated H153 facing a relatively alkaline cytosol would promote Zn(II) binding from the intracellular cavity whereas a protonated H153 facing a relatively acidic periplasm may facilitate Zn(II) release into the extracellular cavity (Fig. 5). As such, an inward pH gradient drives a vectorial Zn(II) efflux in a 1:1 exchange stoichiometry. The dynamic details revealed in the present study explain how a physiological proton gradient, zinc coordination chemistry and water nanofluidics are orchestrated in a dynamic protein structure to overcome the activation barrier to Zn(II) efflux and promote a vectorial Zn(II) movement through an inter-cavity water portal that is highly conserved in the CDF protein family.

Fig. 5. Schematic representation of zinc-for-proton exchange.

based on two existing structural models with the L152 gate open or closed as indicated. The protein conformational change alternates the membrane facing, on-off mode of zinc coordination and protonation-deprotonation of the transport-site in a coordinated fashion.

Methods

Preparation of apo-YiiP and zinc-YiiP for x-ray radiolysis

His-tagged YiiP was over-expressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS cells and purified as described previously3. Briefly, cells in the stationary phase of an overnight auto-induction culture were harvested and lysed mechanically by three passages through a microfluidizer press cell. The resulting membrane vesicles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation, and then solubilized using a detergent buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 7% n-Dodecyl-β-D Maltopyranoside, 0.25 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TECP) and 20% w/v glycerol. The crude membrane extract was applied to a Ni2+-NTA superflow column. After washing the column with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20% w/v glycerol, 0.05% DDM, 0.25 mM TCEP, 30 mM imidazole, YiiP was eluted with an elevated imidazole concentration at 500 mM. The purified His-YiiP was loaded to a 10 KDa cutoff dialysis cassettes against a bulk solution containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 20% w/v glycerol, 0.05% DDM, 0.25 mM TCEP. Thrombin (Novagen) was added into the dialysis cassette at a ratio of 1 unit per mg of His-YiiP. The proteolytic removal of the His-tag was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Prior to X-ray exposure, YiiP was demetallized by incubation with 5 mM EDTA for 30 min. The EDTA-treated sample was then subjected to size-exclusion purification using a TSK 3000SWXL column pre equilibrated with a radiolytic labeling buffer (10 mM NaPi, pH 6.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.02% DDM, 0.1mM TCEP). The purified YiiP is referred to as apo-YiiP thereafter. A total of 2.5 titratable zinc sites in each apo-YiiP monomer was detected by isothermal titration calorimetry3. These zinc sites were mapped to a transport-site in the transmembrane domain (TMD), a surface zinc binding site on the cytoplasmic membrane surface, and a partially occupied binuclear zinc binding site in the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD)13. ZnCl2 was added to 0.1 mM to an aliquot of apo-YiiP to form zinc-YiiP at 10 μM concentration. At this zinc concentration, the transport-site in zinc-YiiP was mostly occupied because the zinc binding affinity of the transport-site is in the μM range3.

Synchrotron X-ray radiolysis, mass spectrometry and data analysis

Apo-YiiP or zinc-YiiP was exposed to an x-ray white beam at beamline X28C of National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory as described previously (Extended Data Fig. 1a) 16,25. Briefly, x-ray beam parameters were optimized to provide a sufficient dose of hydroxyl radical in a millisecond timeframe as judged by a standard fluorophore assay25. A Kintek® quench flow apparatus (KinTek Corporation) was modified to push 200 μl of protein samples through an x-ray window (0.8 mm internal diameter × 4 mm length) at varied flow-speeds that gave an x-ray irradiation time ranging from 2.5 to 20 ms. All irradiations were carried out at 4°C. Unwanted secondary oxidations were quenched within 40 ms by collecting the irradiated samples directly in a tube containing 10 mM methionine amide, and then frozen at −80°C. The 'zero' sample was run under same condition without opening the beamline shutter. Proteolytic cleavage of the irradiated samples was performed using pepsin, trypsin or trypsin chymotrypsin double digestion to obtain maximum sequence coverage. For pepsin digestion, the detergent in the samples was first removed by methanol-water-chloroform precipitation followed by pepsin digestion at 37°C for 10 min. For trypsin and trypsin chymotrypsin digestion, protein samples were incubated with the proteases overnight at 37°C, followed by detergent removal using an affinity spin column (Thermo Scientific). A bottom-up proteomic analysis by reverse phase LC-MS was carried out using Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLC nano LC interfaced to a Fourier Transform LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The digests (~1 pmol) were loaded onto a PepMap reverse-phase trapping column (300 μm × 5 mm C18) to enrich the peptides and wash away excess salts using a nano-HPLC UltiMate-3000 column switching technique; reverse-phase separation was then performed on a C18, PepMap column (75 μm × 15 cm). Buffer A (100% water and 0.1% formic acid) and buffer B (20% water, 80% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid) were employed in a linear gradient. Proteolytic peptides eluted by an acetonitrile gradient (1% per min) were directed to an LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a nanospray ion source operated at a needle voltage of 2.4 kV. Mass spectra were acquired in the positive-ion mode with the following acquisition cycle: a full scan recorded in the Fourier transform analyzer at resolution (R) 100,000 followed by MS/MS of the eight most intense peptide ions in a linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) analyzer. The MS/MS data for peptides and their sites of modifications were manually interpreted with the aid of ProteinProspector algorithm (University of California, San Francisco), ProtMap26 and Bioworks 3.3 (Thermo Scientific). The peak area from the extracted ion chromatograms of a specific peptide fragment with a particular mass-to-charge ratio and associated +14- , +16- or +32-Da sidechain modifications was used to quantify the amount of modification at a given irradiation time. The fraction of unmodification versus the x-ray irradiation time was plotted and fitted to a single exponential function using Origin 7.5 (OriginLabs®) to determine the hydroxyl radical reactivity rate of the sidechain16. All data are presented as mean ± standard error based on three or more independent measurements.

Time-resolved synchrotron X-ray radiolysis

Time-resolved radiolysis was carried out in a modified KinTek® apparatus using a three-step (push-pause-push) flow sequence (Extended Data Fig. 1b) 18,27. A 20 μl of 20 μM apo-YiiP in the radiolysis buffer and an equal volume of 0.2 mM ZnCl2 in the radiolysis buffer were pushed into a T-mixer. After a designated delay time from 0-10 sec, a second push drove the mixed sample through an irradiation cell and then into a collection tube containing methionine-amide to a final concentration of 10 mM. The sample flow speed was calibrated to achieve a 2.5 ms of fixed x-ray irradiation in the irradiation cell. The dead time for the sample to travel from the T-mixer to the irradiation cell was 10 ms. The reaction time was the sum of the dead time and the delay time for the sample to be held in the mixing loop. Mass spectrometric measurements of radiolytic labeling and data analysis followed the same procedure as described above. The extent of radiolytic modification was plotted against the reaction time and fitted with a single exponential function to determine the rate of water accessibility change to the site of radiolytic modification. All data are presented as mean ± standard error based on three or more independent measurements.

Mutagenesis, mutant expression and stability assay

L152 mutations were generated using a Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). The L152 mutants were produced by auto-induction over-expression, DDM solubilization and Ni-NTA affinity purification as described above. The purified proteins were further purified by sizing HPLC using a TSK3000SWXL column equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 12.5% glycerol, 0.05% DDM and 2 mM β-ME. Protein expression was examined before DDM solubilization. Membrane vesicles were directly solubilized by SDS and then subjected to western blot detection using rabbit affinity-purified His-tag polyclonal antibody (catalog #2365) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Western blots were performed three times. Protein stability was monitored by size exclusion HPLC. Equal amounts of purified L152 mutants and YiiP were kept in the HPLC buffer for 24 hours at 4 oC, and then protein aggregates were removed by ultracentrifugation. The resultant supernatants were injected to the TSK column. The eluted peaks were recoded using the wild type YiiP peak as a reference.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this work to the memory of Dr. Peter C. Maloney. This work is supported in part by the National Institute of Health under Grant R01 GM065137 (to D.F), Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Department of Energy (DOE KC0304000 to D.F) and the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering under Grants P30-EB-09998 and R01-EB-09688 (to MRC), The National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-98CH10886.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions M.C. and D.F. conceived the work, S.G. and D.F. designed the experiments, S.G., J.C., R.D. and D. F. performed the experiments, S.G., M.C. and D.F analyzed the data, D.F. interpreted the data and wrote the paper with S.G. and M.C.

References

- 1.Lu M, Chai J, Fu D. Structural basis for autoregulation of the zinc transporter YiiP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1063–1067. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grass G, et al. FieF (YiiP) from Escherichia coli mediates decreased cellular accumulation of iron and relieves iron stress. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao Y, Fu D. Thermodynamic studies of the mechanism of metal binding to the Escherichia coli zinc transporter YiiP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17173–17180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei Y, Fu D. Selective metal binding to a membrane-embedded aspartate in the Escherichia coli metal transporter YiiP (FieF). J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33716–33724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei Y, Fu D. Binding and transport of metal ions at the dimer interface of the Escherichia coli metal transporter YiiP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23492–23502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei Y, Li H, Fu D. Oligomeric state of the Escherichia coli metal transporter YiiP. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:39251–39259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao Y, Fu D. Kinetic Study of the Antiport Mechanism of an Escherichia coli Zinc Transporter, ZitB. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12043–12050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kambe T, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Sasaki R, Nagao M. Overview of mammalian zinc transporters. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:49–68. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3148-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montanini B, Blaudez D, Jeandroz S, Sanders D, Chalot M. Phylogenetic and functional analysis of the Cation Diffusion Facilitator (CDF) family: improved signature and prediction of substrate specificity. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nies DH. Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:313–339. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmiter RD, Cole TB, Quaife CJ, Findley SD. ZnT-3, a putative transporter of zinc into synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14934–14939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemaire K, et al. Insulin crystallization depends on zinc transporter ZnT8 expression, but is not required for normal glucose homeostasis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14872–14877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906587106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu M, Fu D. Structure of the zinc transporter YiiP. Science. 2007;317:1746–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1143748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu G, Chance MR. Hydroxyl radical-mediated modification of proteins as probes for structural proteomics. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3514–3543. doi: 10.1021/cr0682047. doi:10.1021/cr0682047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takamoto K, Chance MR. Radiolytic protein footprinting with mass spectrometry to probe the structure of macromolecular complexes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102050. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta S, et al. Conformational changes during the gating of a potassium channel revealed by structural mass spectrometry. Structure. 2010;18:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angel TE, Gupta S, Jastrzebska B, Palczewski K, Chance MR. Structural waters define a functional channel mediating activation of the GPCR, rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14367–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta S, D'Mello R, Chance MR. Structure and dynamics of protein waters revealed by radiolysis and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14882–14887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209060109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podar D, et al. Metal selectivity determinants in a family of transition metal transporters. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3185–3196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin H, et al. Gain-of-function mutations identify amino acids within transmembrane domains of the yeast vacuolar transporter Zrc1 that determine metal specificity. Biochem J. 2009;422:273–283. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coudray N, et al. Inward-facing conformation of the zinc transporter YiiP revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:2140–2145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215455110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinds BJ, et al. Aligned multiwalled carbon nanotube membranes. Science. 2004;303:62–65. doi: 10.1126/science.1092048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoch E, et al. Histidine pairing at the metal transport site of mammalian ZnT transporters controls Zn2+ over Cd2+ selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7202–7207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200362109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramos S, Schuldiner S, Kaback HR. The electrochemical gradient of protons and its relationship to active transport in Escherichia coli membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:1892–1896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta S, Sullivan M, Toomey J, Kiselar J, Chance MR. The Beamline X28C of the Center for Synchrotron Biosciences: a national resource for biomolecular structure and dynamics experiments using synchrotron footprinting. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2007;14:233–243. doi: 10.1107/S0909049507013118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur P, Kiselar JG, Chance MR. Integrated algorithms for high-throughput examination of covalently labeled biomolecules by structural mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry. 2009;81:8141–8149. doi: 10.1021/ac9013644. doi:10.1021/ac9013644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ralston CY, et al. Time-resolved synchrotron X-ray footprinting and its application to RNA folding. Methods in enzymology. 2000;317:353–368. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]