Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate charge-integration at threshold by cochlear implant listeners using pulse train stimuli in different stimulation modes (monopolar, bipolar, tripolar). The results partially confirmed and extended the findings of previous studies conducted in animal models showing that charge-integration depends on the stimulation mode. The primary overall finding was that threshold vs pulse phase duration functions had steeper slopes in monopolar mode and shallower slopes in more spatially restricted modes. While the result was clear-cut in eight users of the Cochlear CorporationTM device, the findings with the six user of the Advanced BionicsTM device who participated were less consistent. It is likely that different stimulation modes excite different neuronal populations and/or sites of excitation on the same neuron (e.g., peripheral process vs central axon). These differences may influence not only charge integration but possibly also temporal dynamics at suprathreshold levels and with more speech-relevant stimuli. Given the present interest in focused stimulation modes, these results have implications for cochlear implant speech processor design and protocols used to map acoustic amplitude to electric stimulation parameters.

I. INTRODUCTION

It has been proposed that using focused, or restricted stimulation—i.e., electrical stimulation consisting of simultaneously presented pulses of opposing phases on nearby intracochlear channels aimed at reducing current spread and channel interaction—can be beneficial to the field of cochlear implants in two ways. First, by narrowing the spread of the electric field, current focusing may enhance spectral coding by the cochlear implant particularly when used in combination with current steering (Bonham and Litvak, 2008; Srinivasan et al., 2012). Another possibility is that by targeting a smaller group of neurons, focused stimulation may reveal weaknesses in information transmission at each stimulation electrode (Bierer, 2007; Bierer and Faulkner, 2010; Bierer, 2010; Goldwyn et al., 2010; Bierer et al., 2011).

In the present study, we specifically investigated listeners’ sensitivity to changes in pulse phase duration (PPD) using monopolar and more restricted modes of stimulation (bipolar and tripolar). In bipolar stimulation, the net spread of excitation is restricted by returning the current through a second, single intracochlear electrode located near the active electrode. In tripolar or partial tripolar stimulation, all or part of the current is returned through two flanking electrodes adjacent to the active electrodes. Monopolar stimulation, by returning the current through an extracochlear electrode, results in a broader excitation area and requires lower current levels to achieve the same loudness as bipolar or tripolar stimulation. As a result, monopolar stimulation likely results in a greater population of neurons responding at a lower mean probability of firing. Our premise is that sensitivity to PPD reflects neural charge integration, and as such may be indicative of the locus, or site, of excitation (e.g., peripheral process vs central axon of the stimulated neuron) and/or neuronal health (for instance, characteristics of the membrane). Further, PPD sensitivity reflects temporal integration of charge and possibly is related to other forms of temporal sensitivity, such as neuronal and/or behavioral sensitivity to rapid temporal fluctuations. For instance, if a particular neuron has a very high membrane capacitance and long charging time constant, it should behave like a lowpass filter, and we would expect it to be a poor encoder of both temporal fine structure and rapid envelope changes. Given the rising interest in focused stimulation in cochlear implants, it is important to understand the effects of different stimulation modes on the temporal response properties of the electrically stimulated auditory system.

The central axons of the auditory nerve decline both in numbers and diameter with increasing duration of deafness (Nadol, 1997; Leake and Hradek, 1988; Nadol et al., 1989). Longer chronaxie (pulse duration required for a current at twice the rheobase to elicit a criterion response, where rheobase is the lowest asymptotic threshold current for an infinitely long pulse) has been associated with neuronal damage such as demyelination and reduction in fiber diameter in neural modeling studies (Bostock et al., 1983; Colombo and Parkins, 1987; Smit et al., 2008). Smaller numbers of surviving neurons should result in reductions in the summed response, greater susceptibility to noise, and thus, poorer sensitivity to PPD (as well as other stimulus variables). This is also supported by results obtained by Miller et al. (1995) showing declines in the slope of the threshold-duration function over time (i.e., with increasing duration of deafness) in implanted animals. Recent work in deafened guinea pigs suggests that sensitivity to PPD is correlated with nerve survival counts (Prado-Guitierrez et al., 2006); however, a more complex picture is presented by Ramekers et al. (2014), who studied effects of PPDs less than 50 μs.

There are reasons to believe that sensitivity to PPD may be influenced by the stimulation mode in humans. However, a review of the literature suggests conflicting mechanisms when the factors of stimulation mode, neuronal damage, and site of neural excitation (e.g., peripheral process vs central axon) are considered together. It seems reasonable to hypothesize that restricted stimulation involves stronger contributions from surviving peripheral processes closer to the electrode contact, than in monopolar stimulation where the return electrode is outside the cochlear chambers (Miller et al., 2003). Neuronal models suggest lengthened chronaxie when peripheral processes are included (e.g., Smit et al., 2008). If survival of these peripheral processes is better in a particular region and the stimulation is such that they contribute more strongly to the response, then we may expect a longer chronaxie/time constant of integration and shallower strength-duration functions under those conditions. Thus, improved nerve survival is likely to result in shorter time constants and greater sensitivity to PPD when healthy central axons dominate the response, but longer time constants and poorer sensitivity to PPD when peripheral processes dominate the response. This hypothesis is supported by the work of Cartee et al. (2006) which suggests that summation time constants are strong indicators of excitation at different sites (peripheral process vs central axon). Those analyses indicated that longer time constants are associated with peripheral-process excitation and shorter time constants associated with (healthy) central axons. However, when central axons become demyelinated, the time constant might increase, making it difficult to draw conclusions about neural health from time constants (or chronaxie) alone.

Based on observations of electrically evoked compound action potentials and single unit modeling work in cats, Miller et al. (2003) suggested that peripheral processes are preferentially excited under conditions of focused stimulation, particularly at threshold or in low-stimulus-level conditions as in the present study. It is not entirely clear whether the same holds true in humans. There are several differences between animal and human cochlear electroanatomy and neural morphology; further, the method of deafening and the acute nature of animal experiments may result in greater survival of peripheral processes in laboratory animals than in human cochlear implant (CI) patients.

Indeed, previous work in animals provides converging evidence for changes in PPD sensitivity in different stimulation modes. A number of previous behavioral studies of threshold vs PPD functions were conducted using single-pulse stimuli or pulse trains in cats, guinea pigs, macaques, and humans (Shannon, 1985; Pfingst et al., 1991; Moon et al., 1993; Smith and Finley, 1997; Miller et al., 1999). Smith and Finley (1997) reported three time periods of charge integration measured psychophysically in cats: (i) 50–100 μs, during which monopolar and bipolar slopes converge at about −6 dB/doubling of PPD; (ii) 200–1600 μs, during which bipolar slopes are shallower (−3.4 dB/doubling for radial bipolar and −4.4 dB/doubling for longitudinal bipolar on average) than monopolar (−5.9 dB/doubling on average); and (iii) 2500–5000 μs, during which monopolar as well as bipolar slopes become considerably shallower. A somewhat different pattern of changes in slope with PPD had been previously reported by Pfingst et al. (1991) in macaques using a mix of electrode separations. They reported shallower slopes below 500 μs/phase, steeper slopes between 1000 and 2000 μs/phase, and shallower slopes again at very long PPDs. In humans, Moon et al. (1993) reported slopes of −3.6 dB/doubling with bipolar stimulation and PPDs below 500 μs/phase. They reported a steepening of the bipolar slope to −5.71 dB/doubling at higher PPDs. Although this description of slope changes is somewhat different from that described later by Smith and Finley (1997), it is closer to the pattern described by Pfingst et al. (1991) in macaques. It is not clear whether the differences can be entirely attributed to species differences: if so, macaques might provide a closer approximation to humans.

Both Miller et al. (1999) and Smith and Finley (1997) specifically examined the effects of electrode configuration. Results suggested shallow slopes for bipolar electrodes and steeper slopes for monopolar (MP) electrodes, with MP electrodes resulting in the most efficient charge integration (i.e., a halving of threshold for each doubling of pulse phase duration). Smith and Finley reported consistently shallower slopes for more closely separated (radial) bipolar electrodes than for more widely separated bipolar electrodes in cats. This suggested a hierarchy of slopes with increasing separation between the stimulated electrodes. Miller et al. (1999) reported significantly shallower slopes for bipolar electrodes than for monopolar, and their results were consistent across cats, guinea pigs, and macaques. Their dataset did not include a comparison of bipolar and monopolar mode for humans, but the slopes obtained in their human subjects in monopolar mode were consistent with the monopolar slopes obtained in the animals.

When interpreting threshold vs PPD data in CI patients, two hypothetical scenarios can be considered:

Scenario 1: Monopolar stimulation, by creating a larger area of current flow, results in stronger contributions from central axons, while restricted stimulation results in stronger contributions from surviving peripheral processes. In this situation, slopes should be shallower for bipolar/tripolar stimulation (greater proportion of responses dominated by peripheral processes) and steeper when monopolar mode is used (responses dominated by central axons). To the extent that absolute detection thresholds are related to the health of the nerve, higher thresholds should be related to steeper slopes, because greater damage would coincide with fewer surviving peripheral processes overall, and larger numbers of central axons would respond.

Scenario 2: Peripheral processes are absent and restricted stimulation elicits responses from a small group of damaged central axons. In this situation, slopes should also be shallower with focused modes (damaged/demyelinated local group of central axons) and steeper with monopolar modes. If damage to the nerve is extensive, the slopes of strength-duration functions might be shallow for both focused and monopolar modes. To the extent that detection threshold reflects neural health, higher detection thresholds should be related to shallower slopes of threshold-PPD functions (greater overall damage to the central axons).

Although the potential ambiguity in interpretation of the data could be resolved by considering absolute thresholds as an indicator of neural health, absolute thresholds are also affected by extraneous factors such as the distance and angle of the excitable tissue from the electrode source. Threshold levels are by no means unambiguous indicators of neural health, but may provide partially useful information regardless. Thus, Bierer and Faulkner (2010) reported that high thresholds obtained with focused stimulation are related to broadened tuning at the same stimulation sites, suggesting that high focused thresholds are likely partially indicative of poor local function at individual sites.

In summary, the prediction would be the same, regardless of the underlying mechanism. In either case (Scenario 1 or 2), we expect shallower slopes of strength-duration functions for restricted stimulation modes, and steeper slopes for monopolar mode.

In the present study, we compared slopes of threshold-vs-PPD functions obtained on the same electrodes using pulse trains in monopolar, bipolar, and tripolar modes in adult CI patients. In terms of the existing literature, the data presented here extend the previous datasets to include human data on all three modes for the first time. In addition, we investigated the relation between the slopes of these functions and absolute detection threshold. This analysis helped separate the potential confound between the absolute threshold and stimulation mode (as thresholds are generally higher with focused modes). To avoid the very high thresholds necessitated by single-pulse stimulation, pulse-train stimulation was selected at a moderate (and clinically relevant) rate of 1000 pulses/s. Both aspects of the pulse shape—PPD and inter-phase gap (IPG) influence the perceived loudness (as well as neural response strength—e.g., Ramekers et al., 2014). However, the precise interaction of the two remains as yet unclear. In case inter-phase gap might influence listeners’ sensitivity to PPD, measurements were made at several inter-phase gaps. As across-site variation in response is commonly observed in CI listeners, particularly with restricted stimulation modes, measurements were made at four evenly spaced electrode locations in each subject.

II. METHODS

A. Subjects

The participants were eight users (nine ears) of Cochlear CorporationTM devices and six users of Advanced BionicsTM devices. All except one, BTCICH04, were adults. Relevant information is presented in Table I. Bilaterally implanted subjects were tested on the side implanted earliest. An exception was BTN2 who was first implanted with an older, N-22 device on the right side but was tested on her left ear, which was implanted later with a Freedom device. Another exception was BTN3, who was tested on both sides. The later implanted side for BTN3 is referred to as BTN3_LE hereafter. For some participants, data collection was completed over a period of two years. There was no indication that their sensitivity changed during the period of the project. Table I indicates the participants’ ages at initial testing.

TABLE I.

Relevant information about subjects. “Early/Prelingual” refers to patients who had some hearing at birth, but had severe hearing loss at some point during the language acquisition years in development.

| Subject | Onset of deafness | Tested ear | Device | Age at implantation (years) | Age at initial testing (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT_N1 | Early/Prelingual | L.E. a | Freedom | F | 61 | 66 |

| BT_N2 | Early/Prelingual | L.E. a | Freedom | F | 16 | 22 |

| BT_N3 R.E. | Prelingual | R.E. | N-24 | M | 18 | 26 |

| BT_N3 L.E. | Prelingual | L.E. | Freedom | M | 23 | 26 |

| BT_N4 | Early/Prelingual | L.E. | N-24 | F | 41 | 51 |

| BT_N5 | Postlingual | R.E. | N-5 | F | 50 | 52 |

| BT_N6 | Postlingual | R.E. a | N-24 | M | 44 | 54 |

| BT_N7 | Postlingual | R.E. | 24-R | F | 51 | 60 |

| BT_N8 | Postlingual | R.E. a | N-24 | F | 46 | 59 |

| BT_C_01 | Postlingual | R.E. a | Clarion II | F | 31 | 37 |

| BT_C_02 | Postlingual | L.E. a | C-90 K | M | 33 | 42 |

| BT_C_03 | Postlingual | L.E. | Clarion II | M | 55 | 65 |

| BT_C_04 | Early/Prelingual | R.E. | Clarion II | F | 18 | 29 |

| BT_C_05 | Postlingual | L.E | HiRes 90 K | F | 63 | 69 |

| BT_CI_CH_04 | Early/Prelingual | R.E. | Clarion II | M | 06 | 16 |

Indicates bilaterally implanted.

B. Stimuli

Stimuli were trains of charge-balanced, biphasic current pulses, with the objective that the overall duration of each pulse should be no more than approximately half the period of the train (i.e., 500 μs). This necessitated the use of relatively short PPDs and IPGs (the maximum pulse length was 560 μs, comprised of 200 μs/phase pulses with 160 μs IPGs). Specifics for each device are given below, and parameters tested for each subject are provided in Table II. For each subject, the narrowest bipolar and tripolar configurations that yielded measurable thresholds with the shortest PPD and IPG, was used. In several cases, the narrowest bipolar configuration was what is known as BP + 1 [the two active electrodes were two electrode-distances apart, e.g., Els. (electrodes) (3,5)]. In the case of tripolar stimulation, Table II provides σ, the fraction of the current returned to each of the flanking electrodes. Thus, when σ = 0.5, the stimulation is fully tripolar, but for σ = 0.4, 20% of the current is returned to the extracochlear ground electrode. Note that henceforth, all bipolar configurations and all tripolar configurations are referred to as bipolar (BP) and tripolar (TP), respectively.

TABLE II.

Parameters tested in each subject. Under “Stimulation mode” the fraction in parentheses indicates the proportion of current returned via each flanking electrode.

| Subject | Stimulation mode | PPD tested (MP mode) (values in μs) | PPD tested (BP mode) (values in μs) | PPD tested (p/TP mode) (values in μs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT_N1 | MP1, BP + 1 | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N2 | MP1, BP + 2 | 25, 100 | 100, 200 | |

| BT_N3 R.E. | MP1, BP + 1 | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N3 L.E. | MP1, BP + 1 | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N4 | MP1, BP + 1 | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 40, 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N5 | MP1, BP | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 40, 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N6 | MP1, BP + 1 | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 40, 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N7 | MP, BP + 1 | 25, 40, 70, 100 | 70, 100, 140, 200 | |

| BT_N8 | MP1, BP | 25, 40, 70 | 70, 100, 200 | |

| BT_C_01 | MP1, BP + 1, pTP (0.375) | 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 43.104, 96.984, 193.968 |

| BT_C_02 | MP1, BP + 1, pTP (0.45) | 32.328, 96.984 | 32.328, 96.984 | 43.104, 96.984, 193.968 |

| BT_C_03 | MP1, BP+1, pTP (0.375) | 10.776, 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 32.328, 96.984, 193.968 | 43.104, 75.432, 96.984, 193.968 |

| BT_C_04 | MP1, BP + 1, TP (0.50) | 32.328, 96.984 | 32.328, 96.984 | 43.104, 96.984, 193.968 |

| BT_C_05 | MP1, BP + 1, pTP (0.375) | 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 43.104, 96.984, 193.968 |

| BT_CI_CH_04 | MP1, BP + 1, TP (0.50) | 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 32.328, 75.432, 96.984 | 43.104, 96.984, 193.968 |

1. Cochlear CorporationTM devices

Stimuli were 300 ms long trains of biphasic, charge balanced current pulses. Pulse phase duration varied from 25 to 200 μs/phase, and inter-phase gap was either 8, 80, or 160 μs. Pulse trains were presented in either monopolar or bipolar mode. Stimuli were generated and presented via the House Ear Institute Nucleus Research Interface (Robert, 2002), and experiments were controlled via a custom software interface. Stimuli were presented on electrodes (Els.) 6, 10, 14, and 18. Note that in these devices, El. 22 is most apical, and El. 1 is most basal.

2. Advanced BionicsTM devices

Stimuli were 300.65 ms long trains of biphasic, charge balanced current pulses. The PPD varied from 10.776 to 193.968 μs, and IPG was either 10.776 or 161.64 μs. Stimuli were presented in either monopolar, bipolar, tripolar (or partial tripolar) mode. Stimuli were generated and presented via the Advanced Bionics Research Interface and experiments were controlled via the BEDCS software interface made available by Advanced BionicsTM. Stimuli were presented on electrodes 12, 9, 6, and 3. On these devices, El. 1 is most apical, and El. 16 is most basal. The specific PPD conditions tested in each mode are listed in Table II. Note that for some subjects, only two PPDs could be tested, owing to limited availability.

C. Measurements

Psychophysical thresholds were obtained using a two-down, one-up, two-interval, forced choice, adaptive procedure, with minor differences between device types. For CochlearTM devices, the maximum number of trials in each run was set to 55, with a minimum of eight reversals and a maximum of 10 reversals (the run was aborted if eight reversals could not be completed). Initial step sizes were 1 dB or less, and reduced after the first four reversals. For Advanced BionicsTM devices, the maximum number of trials for each run was also set to 55, with the run stopping after 10 reversals. The initial step size was 15 μA or less, and halved after the first three reversals. For both devices, the first four reversals were discarded, and the mean of the remaining reversals was computed as threshold. Each run was repeated at least twice in most cases, and the mean of the measurements calculated to obtain the final threshold. As subject BTC05 was available for a very limited time, only one run was completed for each condition in her case. Some users of the CochlearTM device also had time constraints; in a few instances, the two runs were replaced by one longer run (with a maximum of 70 trials, maximum and minimum number of reversals set to 14 and 10, respectively). In these cases also, the first four reversals were discarded, and the mean of the remaining reversals was calculated as the final threshold. Measurements were made in blocks consisting of at least eight runs (for each condition, four electrodes and two repetitions), and the order of trials was randomized within blocks.

D. Statistical analyses

Curve fitting was done using the nonlinear regression engine in SigmaPlot v. 12. The best-fitting exponents were analyzed using linear mixed effects models (LMEs) in SPSS v. 18. LMEs handle missing data (as in the minority of cases in which curve fitting was unsuccessful) more flexibly and also are more powerful than traditional repeated-measures ANOVAs, allowing the investigation of models with fixed and random effects with different covariance structures and different levels of complexity. The different models were compared using a χ2 likelihood ratio test (Twisk, 2006). The objective was to achieve the best fit with the simplest model (i.e., smallest number of parameters).

III. RESULTS

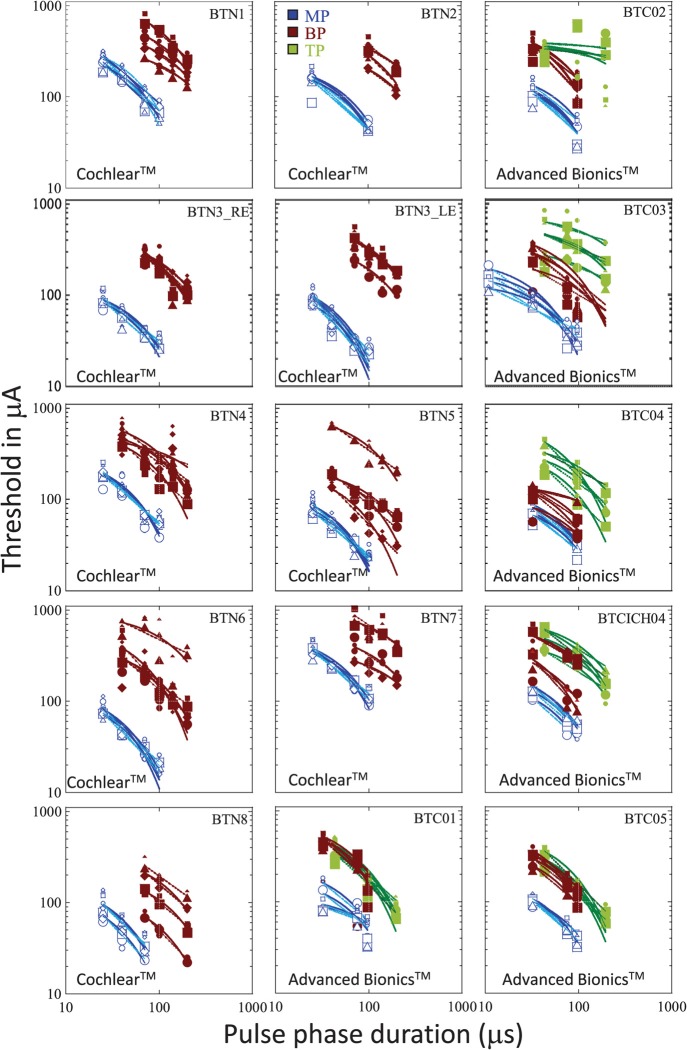

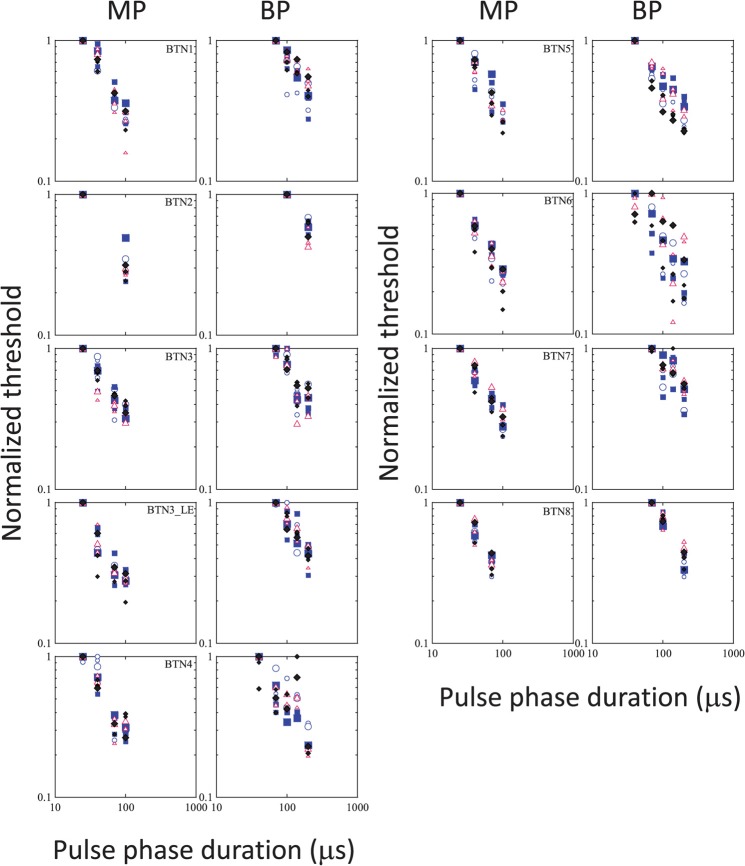

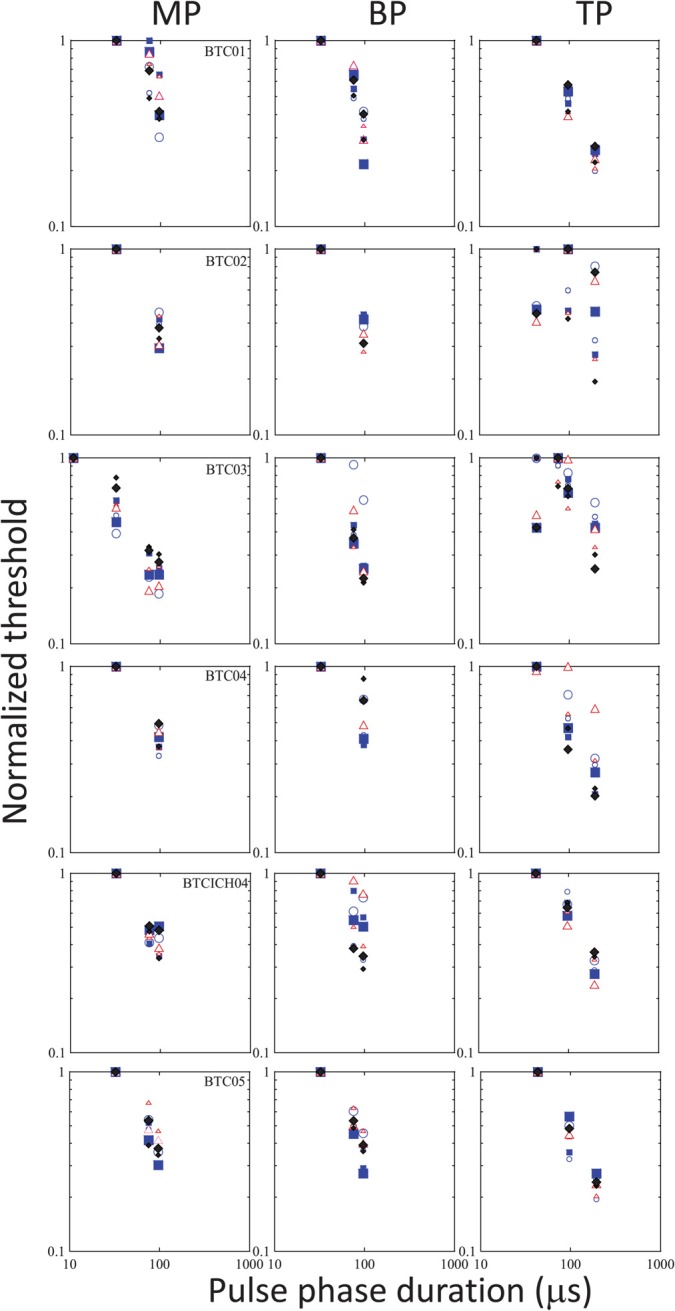

Figure 1 shows the raw data obtained in each subject, with threshold (in μA) plotted as a function of PPD. The different shades represent the different stimulation modes. The different symbols represent data obtained on the different electrodes. Smaller and larger sizes of the symbols show data obtained with the shorter and longer IPGs, respectively. As expected, MP stimulation produced lowest thresholds in general, with higher thresholds obtained in BP or TP modes. We also noted reduced across-site variability in MP mode relative to more focused modes, again consistent with previous literature and expectations (e.g., Pfingst and Xu, 2004). LME analysis conducted separately on the data obtained in each device and for the MP and BP modes, showed that increasing IPGs consistently resulted in a small but statistically significant drop in threshold in each case, but there were no significant interactions between IPG and PPD. Data obtained in the TP mode in Advanced BionicsTM devices, however, showed no significant changes in threshold with IPG, but did show a significant interaction between IPG and PPD [F(3,13.20) = 4.15, p = 0.028]. The overall lack of interaction between the two variables is confirmed by visual inspection of the raw as well as normalized data which show that the shape of the threshold vs PPD function remained relatively unchanged with IPG. This is illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, which show the same thresholds, but normalized to the peak value for each subject. In these plots, data obtained in different stimulation modes are shown in separate panels for the sake of clarity. Within each panel, different symbols show the different electrodes, and the different sizes of each symbol correspond to the different IPGs. It is apparent that the functions remain largely overlapping and do not separate out when the IPG changes. As the IPG-related change in threshold was very small compared to the PPD-related change and as changes in IPG did not result in systematic changes in the shape of the functions, curve-fitting was done with the data pooled across IPGs for each electrode. This proved to be a useful strategy in increasing statistical power.

FIG. 1.

(Color online) Thresholds in μA plotted against PPD. Each panel shows results obtained with a different subject. Within each panel, the parameters are stimulation mode and electrode. The lines show exponential and power function curve fits through the data. Gray, black, and pale gray shades represent stimulation in MP, BP, and TP modes, respectively. Circles, squares, triangles, and diamonds show data obtained in electrodes 6, 10, 14, and 18 for Cochlear CorporationTM users (base to apex), and in electrodes 12, 9, 6, and 3 for Advanced BionicsTM users (base to apex). Increasing size of the symbols corresponds to increasing IPGs (8, 80, and 160 μs for Cochlear CorporationTM devices and 10.776, 161.64 μs for Advanced BionicsTM devices).

FIG. 2.

(Color online) Normalized thresholds plotted against PPD, for Cochlear CorporationTM users. Each pair of side-by-side panels shows data obtained in one subject, with MP and BP modes. The parameters are IPG and electrode. Circles, squares, triangles, and diamonds show data obtained in electrodes 6, 10, 14, and 18, respectively (base to apex). Increasing size of the symbols corresponds to increasing IPGs, as in Fig. 1.

FIG. 3.

(Color online) The same as Fig. 2, but for Advanced BionicsTM users, and with MP, BP, and TP data plotted in the different panels in each row for individual subjects. Circles, squares, triangles, and diamonds show data obtained in electrodes 12, 9, 6, and 3 with increasing sizes of the symbols corresponding to increasing IPGs, as in Fig. 1.

A. The slope of the threshold vs PPD function

The solid lines in Fig. 1 show the best-fitting two-parameter exponential functions following the equation

| (1) |

where Thr = Threshold, T0 = threshold at 0 μs PPD, and b represents the slope of the function. Dotted lines show the best-fitting two-parameter power functions following the equation

| (2) |

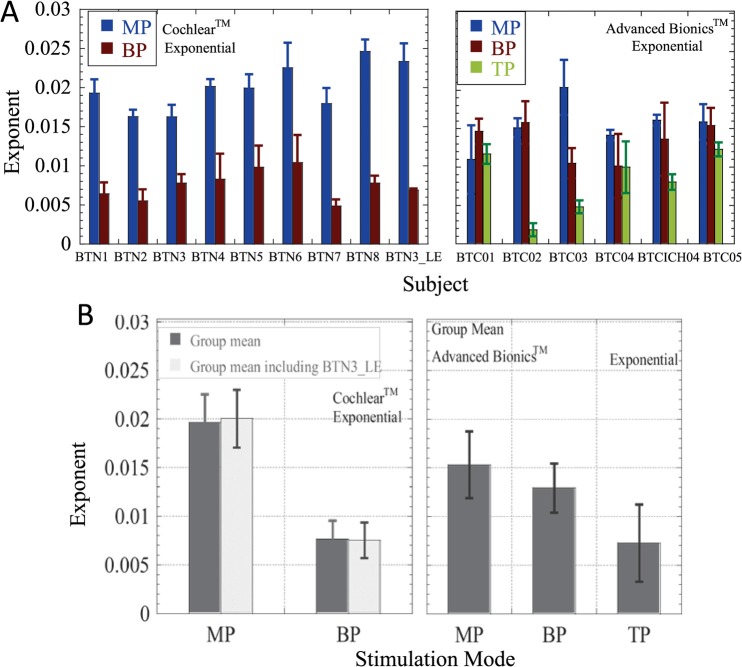

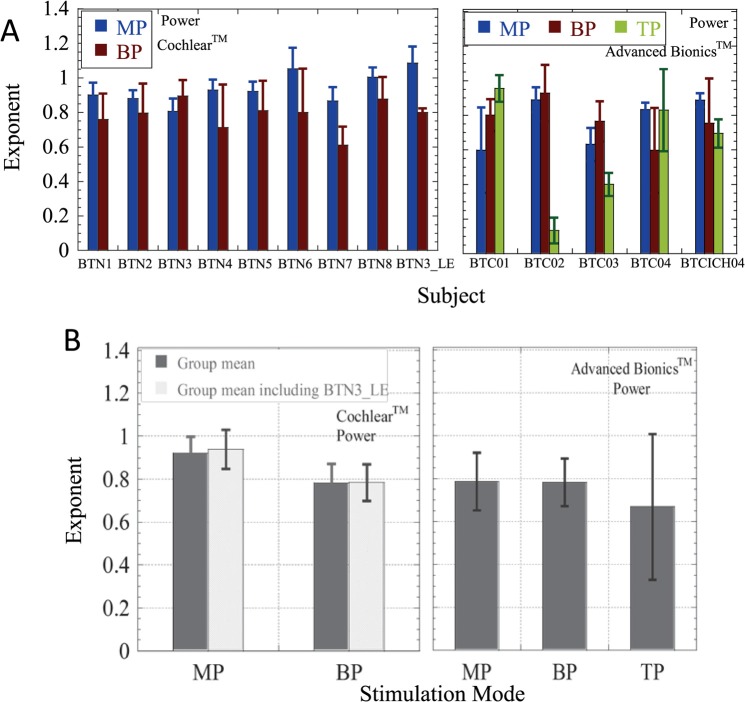

where Thr = Threshold, T1 = threshold at a PPD of 1 μs, and θ is the exponent to which the PPD is raised. As is apparent from the figure, both functions fitted the data reasonably well. The mean R values for exponential fits were 0.91 (s.d. 0.06) in MP mode, 0.87 (s.d. 0.10) in BP mode, and 0.73 (s.d. 0.28) in TP mode. The mean R (correlation coefficient) values for power function fits were 0.92 (s.d. 0.07) in MP mode, 0.88 (s.d. 0.10) in BP mode, and 0.71 (s.d. 0.31) in TP mode. The exponential fit did not converge for five cases in BP mode (BTN2 el. 10; BTN3 el. 6; BTN7 el. 10; BTN8 el. 14; BTN3_LE el. 10) out of the total of 60 curve fits (15 subjects, four electrodes each). Best-fitting exponents of both the exponential and power function fits were used in further statistical analyses. (Note: An attempt to fit the data with three-parameter exponential and power functions led to problems of overfitting limited data with too many parameters, and was abandoned.)

Individual data and group means of the best-fitting exponents are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. The exponents derived for both devices were tested for normality within each mode. The Cochlear CorporationTM data passed the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality both including and excluding the data obtained with the second CI of subject BTN3 (BTN3_LE). The Advanced BionicsTM exponents for exponential fits passed the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality but the exponents for power function fits did not pass the test in MP and TP modes. Therefore, results obtained with the power function fits below should be viewed with caution, particularly given the small sample size.

FIG. 4.

(Color online) (A) (Top). Individual subject's mean slopes (exponents derived from best-fitting exponential fits to the data), taken across the four electrode stimulation sites, for each mode. Left and right hand panels show results obtained with Cochlear CorporationTM and Advanced BionicsTM device users. Error bars show +/− one s.d. from the mean. (B) (Bottom). Group mean slopes for each mode, in Cochlear CorporationTM and Advanced BionicsTM users. Error bars show +/− one s.d. from the mean.

FIG. 5.

(Color online) (A) (Top) and (B) (Bottom). The same as Fig. 4(A) and 4(B), but for slopes (exponents) derived from best-fitting power functions.

1. Cochlear CorporationTM Devices

a. Exponential fits.

First, the data were analyzed excluding the second CI of BTN3 (as the inclusion of the second CI might violate the assumption of independence). For the eight subjects, 60 of the 64 curve fits were successful (all in BP mode). LME models (fixed, repeated factors were electrode and mode) showed significant improvements with the addition of subject-based random intercepts [χ2 (1)= 10.43, p < 0.01] and slopes [χ2 (1) = 15.23, p < 0.0001]. A significant main effect of stimulation mode was observed [F(1,28.04) = 256.878, p < 0.001] but there were no significant effects of electrode. A marginally significant interaction was observed between the two [F(3, 27.42) = 3.79, p = 0.021], primarily due to larger effects of mode (t-test, p = 0.007; p = 0.028 after Bonferroni correction) at electrode 10 than at other electrodes.

LME analysis of the data including both CIs of BTN3 (assuming independence between the two ears) showed similar effects. The model showed significant improvements by inclusion of random intercepts [χ2 (1) = 12.63, p < 0.001]. Results showed a significant effect of mode [F(1, 21.924)= 475.11, p < 0.001], but no effects of electrode and no significant interactions.

2. Power function fits

First, the data were analyzed excluding the second CI of BTN3. For the eight subjects, all of the curve fits were successful. LME analyses showed no significant improvements of the model by including subject-based random intercepts or slopes. A significant main effect of stimulation mode was observed [F(1,28.20) = 22.579, p < 0.001], but there was no main effect of electrode and no significant interaction between the two. Next, the data were analyzed including the second CI of BTN3. The model was significantly improved by including a random intercept, but inclusion of random slopes resulted in failure to converge. A significant main effect of stimulation mode was again observed [F(1, 21.92)= 475.11, p < 0.001], and once again, there was no significant effect of electrode and no interaction between the two.

3. Advanced BionicsTM Devices

a. Exponential fits.

LME analysis (fixed, repeated factors of electrode and mode) showed a significant improvement with the inclusion of random intercepts and slopes [χ2(1) = 5.87, p < 0.02]. A significant effect of stimulation mode was found [F(2, 35.029) = 19.00, p < 0.001] but there were no effects of electrode and no significant interactions. Post hoc paired t-tests of mean exponents showed no significant differences between the MP and BP modes, and a marginally significant difference between MP and TP modes which barely survived the strict Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (p = 0.017; Bonferroni-corrected α = 0.0166).

4. Power function fits

LME analysis with electrode and mode as fixed, repeated factors, showed no significant effect of mode or electrode, and no significant interactions. Further investigations including a random intercept and then both a random intercept and slope resulted in continuing, significant improvements to the model, but no significant effects. As the data violated the assumption of normality, these results should be viewed with caution. The non-parametric Friedman test, which does not require the data to be normally distributed, showed a significant difference between the modes only on electrode 9 [χ2 (2) = 9.00, p = 0.011] but not on the remaining electrodes. Post hoc tests using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed significant differences between MP and TP and BP and TP modes (p = 0.028 for both) but the differences were not significant after applying the strict Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

5. Device-related differences

Independent samples t-tests on the mean exponents obtained from the different subjects with the two devices showed significant differences between the two in MP stimulation mode, with the Advanced BionicsTM devices being associated with shallower slopes in MP mode than Cochlear CorporationTM devices (p = 0.02 for both exponential and power function slopes). A significant difference was also observed with the exponential fit for the BP mode (p < 0.001), with the BP slope being steeper for the Cochlear CorporationTM users than for Advanced BionicsTM users. Although no significant differences were observed between the two sets of BP exponents based on power function fits, these data did not pass the normality test, so the result should be viewed with caution.

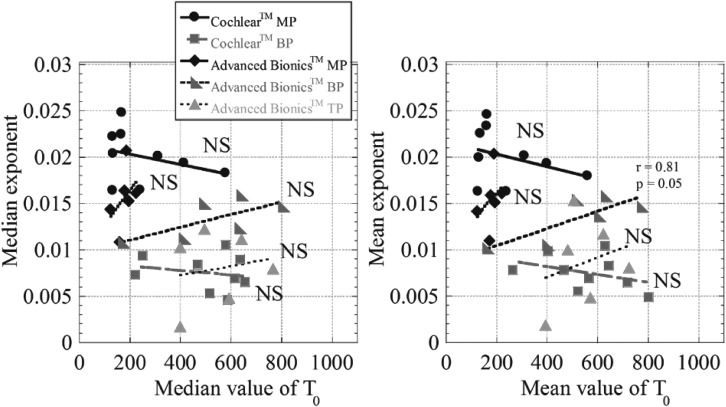

B. The effect of overall threshold on the slope

A potential confound in the findings reported above is that the threshold current varies with stimulation mode, with higher thresholds generally obtained in more restricted modes and lower thresholds in monopolar mode. It is possible that the differences in slope observed in different modes are related to the concurrent differences in threshold current. If so, then thresholds and slopes should be inversely related within modes as well. Figures 6(A) and 6(B) show the median and the mean slopes [exponents in Eq. (1)] obtained for each subject (across electrodes), plotted against the corresponding median and the mean values of T0 in Eq. (1). T0 provides an estimate of the highest theoretical threshold estimated in each experimental condition. The median data are presented alongside the means because the dataset is relatively small and variability was high, particularly for T0 in restricted stimulation modes, with some electrodes having very high thresholds relative to others. Stimulation in BP and TP modes result in higher thresholds and shallower slopes than the MP mode, but no significant correlations were observed between the slopes and T0 within any of the modes.

FIG. 6.

Slopes of best-fitting exponential functions plotted against intercepts (T0) for each stimulation condition and each subject. Left and right hand panels show mean and median values, respectively, calculated across subjects (all electrodes pooled within each subject). The lines represent linear regression through the data for each subject. Data obtained in monopolar, bipolar and tripolar stimulation mode are shown in different shades.

IV. DISCUSSION

The present data extend previous findings in animals and partial data in humans indicating that monopolar stimulation results in steeper slopes of threshold-PPD functions than does more restricted stimulation. This result is clear-cut in the case of Cochlear CorporationTM devices in the present study, but not as clear in the case of Advanced BionicsTM devices, which showed significant reductions in the slopes of exponential functions when stimulation mode was restricted, but not in the slopes of best-fitting power functions. The two functions [Eqs. (1) and (2)] are somewhat different in shape, but as the goodness-of-fit measures do not show clear advantages of one over the other, we opted to analyze slopes derived from both. We interpret the results as indicative of potentially weaker mode-based differences in the slope in the Advanced BionicsTM dataset. One limitation of the present study is the inclusion of different configurations of partial tripolar stimulation within the umbrella of “tripolar” in the analyses. The dataset was too small to allow us to examine effects of different tripolar configurations. Further investigation is needed to paint a clearer picture. Although the Advanced BionicsTM dataset is relatively small, it is valuable in the context of the gap in our knowledge-base. To our knowledge, there are no published, comparable data in humans in the literature.

As discussed in the Introduction, the interpretation of the results is complicated by at least two, somewhat different, issues: first, the possibility that surviving peripheral processes contribute more strongly to the response to focused stimulation and second, that focused stimulation may stimulate smaller numbers of local neurons and the summed response is more reflective of local damage. Carlyon et al. (2005) found a similar independence of threshold vs IPG functions from stimulation mode. We note that our stimuli were designed such that the total duration of each biphasic pulse did not exceed half of the stimulation period. This meant that IPGs used in our study were constrained to a narrow range of short values relative to the range used by Carlyon et al. (2005). Within this restricted range, effects of IPG are expected to be small based on Carlyon et al. findings.

A. The potential effect of compliance limits on the results

One effect that should be considered is that of the voltage compliance limit of the current sources in the device. With focused stimulation modes, high threshold currents may have exceeded such limits in several cases. Let us consider the impact of this on the data: at the shortest PPDs, the thresholds are highest, and the effect of the compliance limit is the greatest, leading to lower threshold currents than actually recorded in our measurements. At the wider PPDs, the thresholds are lower, and the effect of the compliance limit is less, resulting in threshold currents that are closer to those estimated. This means that when the compliance limit was exceeded, the true slope of the Threshold-PPD function would have been shallower than the estimated slope. Thus, if anything, our measurements likely overestimated the slopes of the functions in the more restricted stimulation modes. The overall conclusion of shallower slopes in more restricted modes is not influenced by this factor: However, in future studies, the compliance limit should be included in measurements.

B. Comparison with previous literature

The present data are qualitatively consistent with previous results in other species showing shallower slopes of strength-duration functions in bipolar than in monopolar mode. Although results with tripolar or partial tripolar mode have not been reported in the literature, the present results are also consistent with findings of Smith and Finley (1997) showing progressively shallower slopes with increasingly focused bipolar stimulation mode. Although it was not easy to determine whether power or exponential functions fit the present data better, the neural membrane charging follows an exponential function owing to the resistive-capacitive (leaky integrator) properties of the membrane in its passive state. However, in many instances in the literature, data were analyzed using dB/doubling of phase duration as the index of slope (a variant of the power function fit). One appeal of this measure is that it is relatively simple to define “efficiency” of charging in this way: perfect linear integration would follow a power function slope of −1 (i.e., −6 dB/doubling of phase duration), while shallower slopes would indicate less efficient charging. To facilitate comparison, Table III provides a comparison of mean slopes in dB/doubling of PPD in the present data set. Previous data comparing such slopes across stimulation modes in animal species were often obtained with single-pulse stimuli and across a much larger range of PPDs. With such stimuli, Miller et al. (1999) found MP slopes of −5.3 to −5.9 dB/doubling in macaques, cats, and guinea pigs, BP slopes of −4.2 dB/doubling in humans, and BP slopes of −4 to −5.3 dB/doubling in macaques, cats and guinea pigs. Human data could not be obtained in MP mode with the N-22 electrodes used in the Miller et al. (1999) study. Moon et al. (1993) measured BP slopes in human CI patients using both single pulse and low-rate (100 Hz) pulse train stimuli. They did not observe significant differences in slope between the two. The mean slope for their pulse-train stimuli was −4.25 dB/doubling for pulse durations in the range of the present study. Smith and Finley (1997) report MP, longitudinal BP and radial BP slopes of −6, −6.1, and −5.4 dB/doubling, respectively in five cats attending to single biphasic pulses, again presented over a much wider range of PPDs. Although the pulse trains used in the present study were at a much higher rate than in previous studies, it is reassuring that the present dataset is in reasonable agreement with previously reported slopes.

TABLE III.

Mean threshold-PPD function slopes in dB per doubling of duration. Figures in parentheses indicate standard deviations.

| Stimulation mode | MP | BP | TP |

|---|---|---|---|

| CochlearTM | −5.65 (0.55) | −4.72 (0.51) | N/A |

| Advanced BionicsTM | −4.72 (0.81) | −4.71 (0.67) | −4.02 (2.04) |

C. Mechanisms

The precise morphology and distribution of surviving auditory nerve neurons in human cochlear implant patients is not well understood. The data that are available from human temporal bones are sparse, mixed, and possibly further complicated by age/other health factors. Regardless, it seems clear that peripheral processes die out first in the overall degeneration sequence (e.g., Nadol, 1997). It may be that even when peripheral processes remain, their numbers are few and variable from site to site. Across-site variation in our results, particularly evident with restricted stimulation modes, is likely to reflect variability in both peripheral process survival and the health of stimulated central axons. The cell body is myelinated in humans; however, the fact that the present data largely confirm previous findings in animals, suggests that this difference in myelination did not contribute greatly to the overall pattern of results. The size and shape of the stimulating field changes with stimulation mode (Kral et al., 1998). The positive and negative phases of bipolar and tripolar stimuli are likely to stimulate different populations of neurons as well, and both the spatial pattern and the temporal dynamics may change across the duration of each pulse. Mechanisms of temporal integration and recovery across pulses within the pulse train may also differ from mode to mode. These factors are not well understood at present, even at the level of neural modeling studies. What is known is that the reduction in the numbers of surviving central axons in animals, is related to changes in temporal coding at the neural level (reflected in longer refractory periods, abnormal bursting activity, etc.; e.g., Shepherd et al., 2004).

D. Implications for clinical speech processors

The present results have important implications for clinical speech processors for cochlear implants, as they provide confirmation of previous findings in animals showing that charge integration is likely to be different across stimulation modes. This suggests that the mapping of acoustic amplitude to electrical charge might need to be different for different combinations of stimulation mode and PPD. Given the recent interest in restricted stimulation, it would also be of considerable interest to understand the extent to which such differential processing would persist at suprathreshold levels and be reflected in other measures of temporal coding. A slower charge integration process implies greater membrane capacitance and poorer temporal coding overall. The spectral degradation in cochlear implants requires greater emphasis on temporal envelope cues for different aspects of speech perception, including phoneme recognition, gender identification and speech intonation recognition (Xu et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2004; Winn et al., 2012, 2013; Peng et al., 2009, 2012). If future experiments show that stimulation mode influences temporal coding at both threshold and suprathreshold levels, speech coding or speech processor settings may need to be altered depending on the mode. Such differences may not be apparent when testing speech perception in quiet, but in challenging listening situations when access to redundant speech cues is limited (by background noise or reverberation), any mode-related differences may be amplified.

At present, a primary limitation in CIs is their inability to provide the level of spectro-temporal resolution required of “normal” auditory perception. Given this limitation, other approaches need to be considered. In recent years, Pfingst and colleagues (e.g., Garadat et al., 2012) have shown that electrode-selection based on psychophysical parameters such as masked modulation detection, can result in significant improvements in speech perception by CI patients. If stimulation in different modes results in differences in psychophysical sensitivity to temporal parameters and/or provides insight into nerve survival mechanisms as has been suggested in recent animal studies, electrode-selection combined with mode-selection at each site, may result in even greater improvements in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant no. R01 DC004786 and start-up funds from Boys Town National Research Hospital. Subject recruitment was facilitated by the Human Subjects Research Core of NIH grant no. P30 DC004662 (PI: Dr. Michael Gorga). We are grateful to all the CI patients who participated for their efforts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bierer, J. A. (2007). “ Threshold and channel-interaction in cochlear implant users: Evaluation of the tripolar electrode configuration,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121, 1642–1653 10.1121/1.2436712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierer, J. A. (2010). “ Probing the electrode−neuron interface with focused cochlear implant stimulation,” Trends Amplif. 14, 84–95 10.1177/1084713810375249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierer, J. A. , and Faulkner, K. F. (2010). “ Identifying cochlear implant channels with poor electrode−neuron interface: Partial tripolar, single-channel thresholds and psychophysical tuning curves,” Ear Hear. 31, 247–258 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181c7daf4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierer, J. A. , Faulkner, K. F. , and Tremblay, K. L. (2011). “ Identifying cochlear implant channels with poor electrode−neuron interfaces: Electrically evoked auditory brain stem responses measured with the partial tripolar configuration,” Ear Hear. 32, 436–444 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181ff33ab [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonham, B. H. , and Litvak, L. M. (2008). “ Current focusing and steering: modeling, physiology, and psychophysics,” Hear. Res. 242, 141–153 10.1016/j.heares.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bostock, H., Sears, T. A. , and Sherratt, R. M. (1983). “ The spatial distribution of excitability and membrane current in normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibres,” J. Physiol. 341, 41–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlyon, R. P. , van Wieringen, A., Deeks, J. M. , Long, C. J. , Lyzenga, J., and Wouters. J. (2005). “ Effect of inter-phase gap on the sensitivity of cochlear implant users to electrical stimulation,” Hear. Res. 205, 210–224 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartee, L. A. , Miller, C. A. , and van den Honert, C. (2006). “ Spiral ganglion cell site of excitation I: Comparison of scala tympani and intrametal electrode responses,” Hear. Res. 215, 10–21 10.1016/j.heares.2006.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo, J., and Parkins, C. W. (1987). “ A model of electrical excitation of the mammalian auditory-nerve neuron,” Hear. Res. 31, 287–311 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90197-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu, Q -J., Chinchilla, S., and Galvin, J. J. (2004). “ The role of spectral and temporal cues in voice gender discrimination by normal-hearing listeners and cochlear implant users,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 5, 253–260 10.1007/s10162-004-4046-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garadat, S. N. , Zwolan, T. A. , and Pfingst, B. E. (2012). “ Across-site patterns of modulation detection: Relation to speech recognition,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 131, 4030–4041 10.1121/1.3701879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldwyn, J. H. , Bierer, S. M. , and Bierer, J. A. (2010). “ Modeling the electrode−neuron interface of cochlear implants: effects of neural survival, electrode placement, and the partial tripolar configuration,” Hear. Res. 268, 93–104 10.1016/j.heares.2010.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kral, A., Hartmann, R., Mortazavi, D., and Klinke, R. (1998). “ Spatial resolution of cochlear implants: The electrical field and excitation of auditory afferents,” Hear. Res. 121, 11–28 10.1016/S0378-5955(98)00061-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leake, P. A. , and Hradek, G. T. (1988). “ Cochlear pathology of long term neomycin induced deafness in cats,” Hear. Res. 33, 11–33 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90018-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller, A. L. , Smith, D. W. , and Pfingst, B. E. (1999). “ Across-species comparisons of psychophysical detection thresholds for electrical stimulation of the cochlea: II. Strength-duration functions for single, biphasic pulses,” Hear. Res. 135, 47–55 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00089-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, C. A. , Abbas, P. J. , Nourski, K. V. , Hu, N., and Robinson, B. K. (2003). “ Electrode configuration influences action potential initiation site and ensemble stochastic response properties,” Hear. Res. 175, 200–214 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00739-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, C. A. , Faulkner, M. J. , and Pfingst, B. E. (1995). “ Functional responses from guinea pigs with cochlear implants. II. Changes in electrophysiological and psychophysical measures over time,” Hear. Res. 92, 100–111 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00205-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon, A. K. , Zwolan, T. A. , and Pfingst, B. E. (1993). “ Effects of phase duration on detection of electrical stimulation of the human cochlea,” Hear. Res. 67, 166–178 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90244-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadol, J. B. , Jr. (1997). “ Patterns of neural degeneration in the human cochlea and auditory nerve: Implications for cochlear implantation,” Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 117, 220–228 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadol, J. B. , Jr., Young, Y. S. , and Glynn, R. J. (1989). “ Survival of spiral ganglion cells in profound sensorineural hearing loss: implications for cochlear implantation,” Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 98, 411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng, S. C. , Chatterjee, M., and Lu, N. (2012). “ Acoustic cue integration in speech intonation recognition with cochlear implants,” Trends Amplif. 16, 67–82 10.1177/1084713812451159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng, S. C. , Lu, N., and Chatterjee, M. (2009). “ Effects of cooperating and conflicting cues on speech intonation recognition by cochlear implant users and normal hearing listeners,” Audiol. Neurootol. 14, 327–337 10.1159/000212112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfingst, B. E. , DeHaan, D. R. , and Holloway, L. A. (1991). “ Stimulus features affecting psychophysical detection thresholds for electrical stimulation of the cochlea. I: Phase duration and stimulus duration,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 90, 1857–1866 10.1121/1.401665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfingst, B. E. , and Xu, L. (2004). “ Across-site variation in detection thresholds and maximum comfortable loudness levels for cochlear implants,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 5(1 ), 11–24 10.1007/s10162-003-3051-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prado-Guitierrez, P., Fewster, L. M. , Heasman, J. M. , McKay, C. M. , and Shepherd R. K. (2006). “ Effect of interphase gap and pulse duration on electrically evoked potentials is correlated with auditory nerve survival,” Hear. Res. 215, 47–55 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramekers, D., Versnel, H., Strahl, S. B. , Smeets, E. M. , Klis, S. F. , and Grolman W. (2014). “ Auditory-nerve responses to varied inter-phase gap and phase duration of the electric pulse stimulus as predictors for neuronal degeneration,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 15(2 ), 187–202 10.1007/s10162-013-0440-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert, M. E. (2002). House Ear Institute Nucleus Research Interface User's Guide (House Ear Institute, Los Angeles, CA: ), pp. 1–45 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shannon, R. V. (1985). “ Threshold and loudness functions for pulsatile stimulation of cochlear implants,” Hear. Res. 18, 135–143 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90005-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shepherd, R. K. , Roberts, L. A. , and Paolini, A. G. (2004). “ Long-term sensorineural hearing loss induces functional changes in the rat auditory nerve,” Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 3131–3140 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smit, J. E. , Hanekom, T., and Hanekom, J. J. (2008). “ Predicting action potential characteristics of human auditory nerve fibres through modification of the Hodgkin–Huxley equations,” S. Afr. J. Sci. 104, 284–292 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, D. W. , and Finley, C. C. (1997). “ Effects of electrode configuration on psychophysical strength-duration functions for single biphasic electrical stimuli in cats,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 2228–2237 10.1121/1.419636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srinivasan, A. G. , Shannon, R. V. , and Landsberger, D. M. (2012). “ Improving virtual channel discrimination in a multi-channel context,” Hear. Res. 286, 19–29 10.1016/j.heares.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Twisk, J. W (2006) Applied Multilevel Analysis: A Practical Guide (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK: ). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winn, M. B. , Chatterjee, M., and Idsardi, W. J. (2012). “ The use of acoustic cues for phonetic identification: Effects of spectral degradation and electric hearing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 131, 1465–1479 10.1121/1.3672705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winn, M. B. , Chatterjee, M., and Idsardi, W. J. (2013). “ Roles of voice onset time and F0 in stop consonant voicing perception: effects of masking noise and low-pass filtering,” J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 56, 1097–1107 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0086) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu, L., Thompson, C. S. , and Pfingst, B. E. (2005). “ Relative contributions of spectral and temporal cues for phoneme recognition,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 3255–3267 10.1121/1.1886405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]