Abstract

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is characterized by dark, coarse and thickened skin with a velvety texture, being symmetrically distributed on the neck, the axillae, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and groin folds, histopathologically characterized by papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis of the skin. A high prevalence of AN has been observed recently. Different varieties of AN include benign, obesity associated, syndromic, malignant, acral, unilateral, medication-induced and mixed AN. Diagnosis is largely clinical with histopathology needed only for confirmation. Other investigations needed are fasting lipoprotein profile, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, hemoglobin and alanine aminotransferase for obesity associated AN and radiological investigations (plain radiography, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging/computerized tomography) for malignancy associated AN. The most common treatment modalities include retinoids and metformin.

Keywords: Acanthosis nigricans, insulin resistance, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is characterized by dark, coarse and thickened skin with a velvety texture, being symmetrically distributed on the neck, the axillae, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and groin folds, histopathologically characterized by papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis of the skin. The term AN was originally proposed by Unna, but the first case was described by Pollitzer and Janovsky in 1891.[1]

PREVALENCE OF ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS

Due to the rising prevalence of obesity and diabetes a high prevalence of AN has been observed recently. The prevalence varies from 7% to 74%, according to age, race, frequency of type, degree of obesity and concomitant endocrinopathy. It is most common in Native Americans, followed by African Americans, Hispanics, and Caucasians. Hud et al. demonstrated predominance of AN in black women when compared to white women (prevalence <1%). Malignant AN is less common.

CLASSIFICATION OF ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS

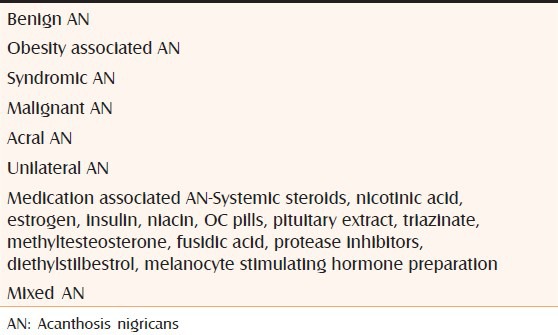

Curth classified AN into malignant, benign, and syndromic or pseudo AN. Hernandez-Perez proposed more simplified classification: simple AN not related to malignancy and paraneoplastic AN. Burke et al. classified AN according to the severity on a scale of 0-4 based on how many areas are affected. This scale is easy to use, having a high inter-observer reliability that correlates with fasting insulin and body mass index (BMI).[1] Classification of AN is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

AN classification

PATHOGENESIS

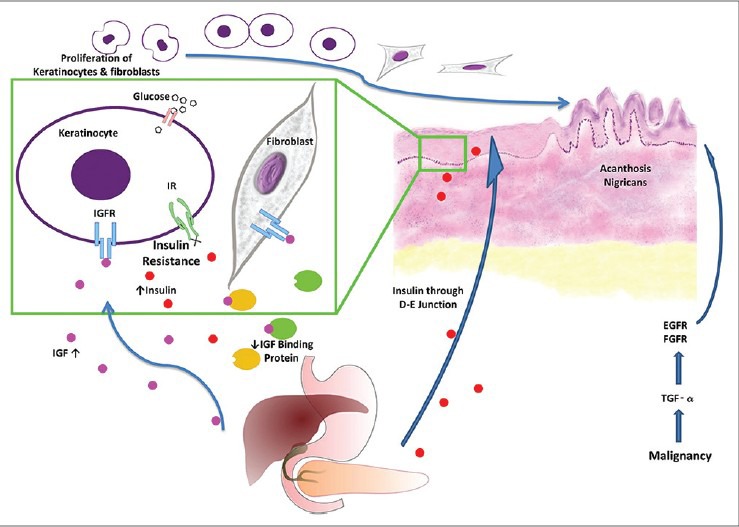

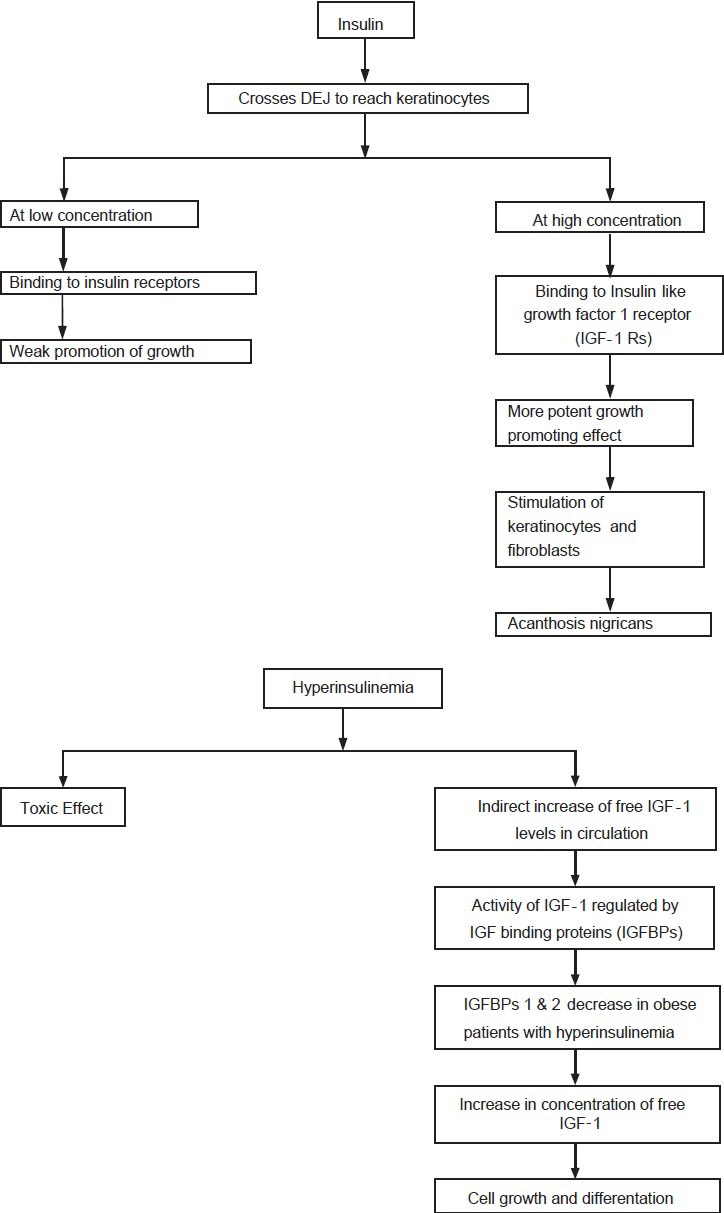

Insulin has been demonstrated to cross dermoepidermal junction (DEJ) to reach keratinocytes. At low concentrations, insulin regulates carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism and can weakly promote growth by binding to “classic” insulin receptors. At higher concentrations, however, insulin can exert more potent growth-promoting effects through binding to insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors (IGF-1Rs) that are similar in size and subunit structure to insulin receptors, but bind IGF-1 with 100- to 1000-fold greater affinity than insulin. The binding stimulates proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, leading to AN [Figure 1].[2]

Figure 1.

Etiopathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans (Image courtesy of Dr. Ashwin Kosambia, Consultant Dermatologist, Mumbai, India)

Hyperinsulinemia not only causes AN by exerting a direct toxic effect,[2] but indirectly by increasing free IGF-1 levels in circulation. The activity of IGF-1 is regulated by insulin-like growth binding proteins (IGFBPs), which increase IGF-1 half life, deliver IGFs to target tissues and regulate levels of metabolically active “free” IGF-1. IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-2 are both decreased in obese subjects with hyperinsulinemia, increasing plasma concentrations of free IGF-1, which promotes cell growth and differentiation [Flow Chart 1].

Flow Chart 1.

Highlighting role of IGF on signal pathways and on keratinocytes and melanocytes

Observations that insulin-dependent activation of IGF-1Rs can facilitate AN development are (1) IGF receptors are found in cultured fibroblasts and keratinocytes. (2) Insulin can cross DEJ and at high concentrations can stimulate growth and replication of fibroblasts. (3) Severity of AN in obesity correlates positively with fasting insulin concentration. Thus, insulin may promote AN through direct activation of the IGF-1 signaling pathway. The predilection of AN for areas such as neck and axillae suggests that perspiration and/or friction may be necessary cofactors [Flow Chart 1].

Unknown autoantibodies other than insulin-receptor antibody have been implicated; this could explain the effectiveness of cyclosporine in treating AN with autoimmune manifestations.[3]

Insulin and IGF-1 levels are affected by hepatitis C infection and both of them may be implicated in etiogenesis of acrochordons and AN through their proliferative and differentiating properties.[4]

MALIGNANCY ASSOCIATED ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS OR ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS MALIGNA

Acanthosis nigricans maligna (ANM) might be explained by elevated levels of transforming growth factor (TGF-α), exerting effects on epidermal tissue through epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor. IGF-1, fibroblast growth factor, and melanocyte stimulating hormone α that regulates melanocyte pigmentation and stimulates growth of keranocytes, can play a role in the pathogenesis of hyperplasia and hyperpigmentation. TGF-α produced by cancer cells is structurally similar to EGF-α, interacts with the same receptor on the cell surface, probably binding with it in different sites. The receptor for EGF is found on normal epidermal cells, particularly on actively proliferating cells of the basal layer where it is involved in growth and differentiation of normal keratinocytes. TGF-α and its receptor participate in tumor progression through auto and paracrine secretion leading to autostimulation. When these growth factors are produced by the primary tumor and circulate in large quantities, they may cause epidermal cell proliferation, leading to AN. Systemic immunologic response to the primary tumor as a cause cannot be discarded.[5]

Clinical features

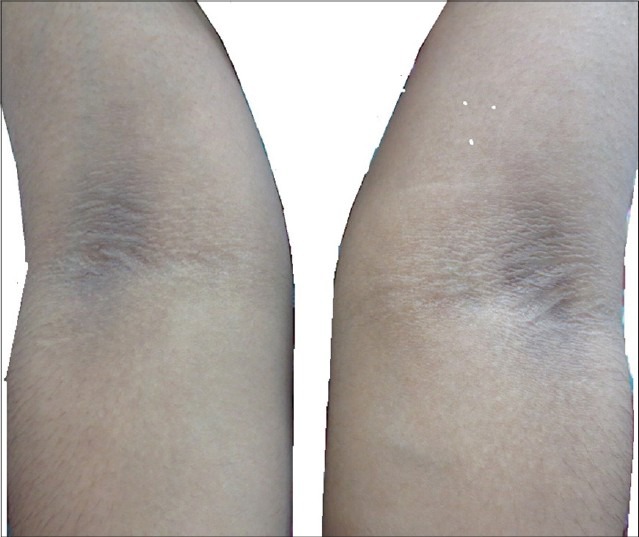

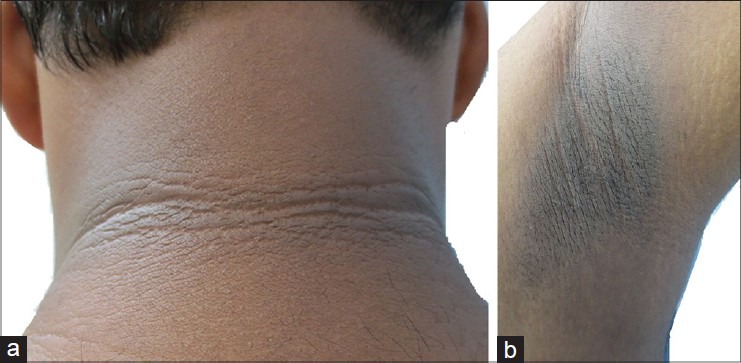

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by dark, coarse, thickened skin with a velvety texture [Figure 2a and b].[6] The earliest change is grey-brown/black pigmentation with dryness and roughness that is palpably thickened and covered by small papillomatous elevations, giving it a velvety texture. As thickening increases, skin lines are further accentuated and the surface becomes mammilated and rugose, with the development of larger warty excrescences.[7] AN is usually asymptomatic, but occasionally, it can be pruritic. The lesions are symmetrically distributed and affect back and sides of neck, axillae, groin, and ante-cubital and popliteal areas [Figures 3 and 4].[6,7] Neck is the most common site affected (99%) in children when compared with axillae (73%). Face, eyelids, flexor and extensor surface of elbows and knees, dorsa of joints of hands, umbilicus, external genitalia, inner aspects of thighs and anus are also involved [Figures 5 and 6].[7] With extensive involvement, lesions can be found over the areolae, conjunctiva, and lips. Involvement of mucous membranes is uncommon, but oral mucous membrane may show delicate velvety furrows.[7] Generalized involvement can be a rare manifestation of certain types of AN, being common in adults with underlying malignancy. Tripe palms presents as rugose hyperkeratosis and prominent dermatoglyphics of palms, likened to bovine gut lining. It is paraneoplastic in occurrence associated with malignancy in 90%, gastric cancer being the most frequent. Periocular distribution is seen in insulin resistance (IR).[6]

Figure 2.

(a) Characteristic dark, coarse, thickened skin with a velvety texture of acanthosis nigricans (AN). (b) AN of the axillae with skin tags

Figure 3.

Acanthosis nigricans on the sides of the neck

Figure 4.

Acanthosis nigricans of the antecubital fossa

Figure 5.

Acanthosis nigricans on the dorsal aspect of interphalangeal joints

Figure 6.

Acanthosis nigricans of the external genitalia and inner aspect of thighs

TYPES OF ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS

Obesity associated acanthosis nigricans (pseudo-acanthosis nigricans)

Obesity is the most common cause of AN. Lesions may appear at any age, but are more common in adulthood. More than half the adults who weigh >200% of their ideal body weight have AN. Lesions are weight dependent, with regression following weight reduction. Insulin resistance is often present in these patients.

Medication associated acanthosis nigricans

This may appear as an adverse effect of several medications [Table 1] that promote hyperinsulinemia. Lesions regress following discontinuation of the offending medication. Erickson et al. first described AN as a rare local cutaneous side-effect of insulin injection. Prescription of the correct insulin and use of proper technique will prevent AN development.[8]

Syndromic acanthosis nigricans

It may occur as two types: type A and Type B. The Type A syndrome hyperandrogenism IR (HAIR-AN syndrome) presents with hyperandrogenemia, IR, and AN. The Type B syndrome occurs in women with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, ovarian HA, or autoimmune disease.

Auto-immune acanthosis nigricans

It is due to the development of antibodies to insulin receptors in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus.[9]

Acral acanthosis nigricans (acralacanthotic anomaly)

It occurs in otherwise healthy patients. It is most common in dark-skinned individuals (African American descent), lesions being prominent over the dorsal aspects of hands and feet.

Unilateral acanthosis nigricans (nevoid acanthosis nigricans)

It is a rare form of AN, inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Lesions are unilateral along lines of Blaschko and may become evident during infancy, childhood, or adulthood. Lesions occur over the face, scalp, chest, abdomen, especially periumbilical area, back and thigh. Lesions can enlarge gradually before stabilizing or regressing.[6,7] Unilateral nevoid AN is not related to endocrinopathy.[10]

Familial acanthosis nigricans

It is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis beginning during early childhood, but may manifest at any age. The condition often progresses until puberty after which it stabilizes or regresses.

Benign genetic acanthosis nigricans

It is a rare autosomal dominant disorder presenting at birth or developing during childhood without endocrinopathy.

Acanthosis nigricans maligna occurs in the course of adenocarcinomas of abdominal organs (70-90%), particularly gastric cancer (55-61%)[7] followed by adenocarcinoma of pancreas, ovary, kidneys, bladder, bronchi, thyroid, bile duct, breast, and esophagus. Onset may be related to medication usage. It is clinically indistinguishable from benign forms, but ANM appears abruptly and exuberantly. Acrochordons are often found in affected areas [Figure 4]. Lesions may be present over the oral, nasal and laryngeal mucosa, esophagus and areola of nipple. Papillomatous lesions on the eyelids and conjunctiva may occur. Leukonychia and nail hyperkeratosis has been reported. In one-third of cases skin changes occur before signs of cancer, in another one-third AN and neoplasm arise simultaneously and in remaining one third, skin findings manifest after diagnosis of cancer.[8] Warning signs that call for evaluation for malignancy in AN patients include age >40 years, not having any previous endocrine disorder or any genetically determined disease, unintentional weight loss, rapid onset of extensive AN, symptomatic lesions, atypical sites, tripe palms, florid cutaneous papillomatosis, and sign of Leser–Trélat.[11] Regression of AN occurs with treatment of the malignancy. Reappearance may suggest recurrence or metastasis of the primary tumor.

Mixed-type acanthosis nigricans

It occurs when a patient with one of the above types of AN develops new AN lesions of a different etiology. An example would be an overweight patient with obesity-associated AN who subsequently develops malignant AN.[6,12] Conditions that manifest with AN are mentioned in Table 2.

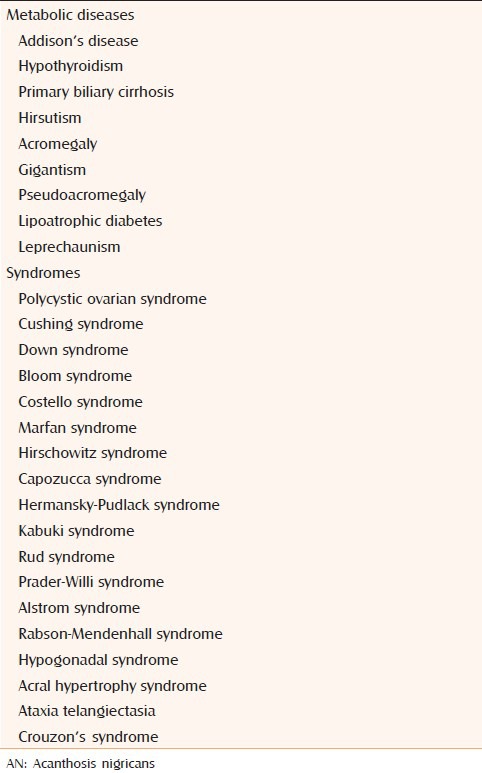

Table 2.

Conditions that manifest with AN

INVESTIGATIONS

Diagnosis is largely clinical with histopathology needed only for confirmation. Histological findings are similar in all forms of AN with papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis and hyperpigmentation of the basal layer. The dermal papillae project upwards as finger-like projections. The valleys between papillae show mild acanthosis and are filled with keratotic material. Clinically observed hyperpigmentation is due to hyperkeratosis and clinical thickening rather than to melanin.[6,9] In ANM proliferation of kerantinocytes with hyperkeratosis dominates and with minimal hyperpigmentation. Spectroscopic and colorimetric measurements combined with chemometric analysis methods provide sensitive and specific diagnosis of AN.[13]

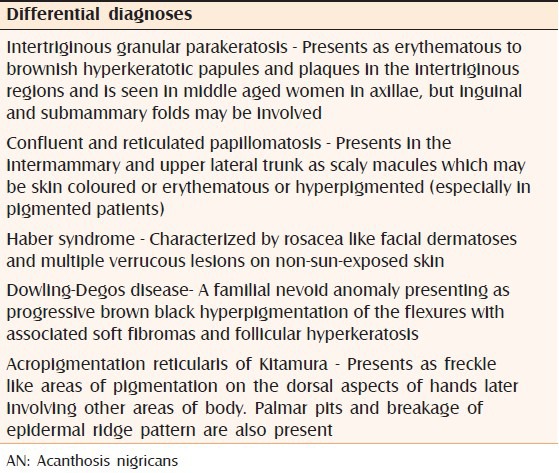

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Table 3 mentions the differential diagnoses of AN.

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of AN

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS AND OBESITY

Patients with AN, especially childhood benign AN, are at risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperinsulinemia, IR and type 2 diabetes and AN may be used as reliable index of IR.[14] But obesity is a more important determinant of IR than AN, hence AN should not be used as exclusive marker for predicting which overweight children have excess insulin levels.

Urrutia-Rojas et al. suggested that mothers of AN-positive children are likely to have abnormalities of fuel metabolism compared with mothers of AN-negative children. Fathers of AN-positive children are more likely to have blood glucose levels ≥26 mg/dL. They suggested that screening children for AN is an effective strategy for identifying adults with prediabetes.[15] Investigations for all overweight adults and children include fasting lipoprotein profile, fasting glucose, hemoglobin, fasting insulin, and alanine aminotransferase.

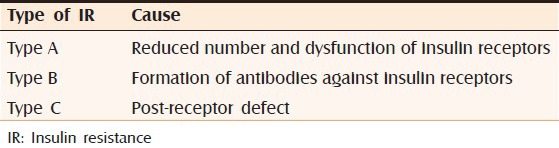

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

Insulin resistance is a metabolic disorder in which target cells fail to respond to normal levels of circulating insulin, resulting in compensatory hyperinsulinemia. IR has been associated with AN and acrochordons which may represent an easily identifiable sign of IR and noninsulin-dependent diabetes. AN is so closely associated with IR that it has been called a clinical surrogate for laboratory determined hyperinsulinemia. Katie S in their study observed that posterolateral neck texture had the highest sensitivity (96%) for IR compared with neck/axillary texture and pigment and proposed the term insulin neck (visibly increased texture on posterolateral neck appearing as visible lines and/or furrows and ridges) for this finding. They concluded that neck texture exhibits both greater sensitivity and specificity than neck pigment for AN detection, because visible roughness of the neck is recognizable without touching or disrobing patient, affording an instant assessment of AN. Furthermore, texture grading avoids possible confounding by sun-induced pigmentation. They suggested that all patients with elevated BMI should be examined for insulin neck and if neck texture is normal, IR is less likely to be present.[16] IR occurs in 20-25% of the individuals. Types of IR are mentioned in Table 4. Obese patients and patients with polycystic ovary syndrome have Type A IR.

Table 4.

Types of insulin resistance

Methods for detecting insulin resistance Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic glucose clamp technique

This technique is a gold standard and reference method for quantifying insulin sensitivity because it directly measures effects of insulin in promoting glucose utilization under steady-state conditions in vivo. However, its calculation is complicated and impractical.

Homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance

The mathematical model of the normal physiological dynamics of insulin and glucose produced the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA), which provided equations for estimating IR (HOMA-IR) and β-cell function from simultaneous fasting measures of insulin and glucose levels. HOMA was first developed in 1985 by Matthews et al. It has been proved to be a robust clinical and epidemiological tool for the assessment of IR. It has a good and linear correlation with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp method.

It is calculated as

HOMA-IR = Fasting glucose (mmol) × Fasting insulin (uU/mL)/22.5. IR is diagnosed when the result is >2.71.

Fasting insulin level

Measurement of fasting insulin level has been considered most practical approach for the measuring of IR as it correlates well with IR. Its use is limited because of a high proportion of false-positive results and lack of standardization.

Glucose/insulin

This ratio has been used in studies as an index of IR. It is a highly sensitive and specific measurement of insulin sensitivity. In adults, a ratio of <4.5 is abnormal, whereas in prepubertal children <7 is abnormal.[6]

Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) proves to be a first-rate index of IR in comparison with clamp-IR. It provides a consistent and precise index of insulin sensitivity with better positive predictive power. It is calculated as:

QUICKI = 1/(log[Insulin μU/mL] + log[Glucosemg/dL])

Patients with QUICKI index below 0.357 tend to have a higher risk of IR or frequently present with manifestations typical of metabolic syndrome.

Glucose insulin product

Product of plasma glucose and insulin concentrations has been considered an index of whole-body insulin sensitivity and it provides better index of insulin sensitivity. If plasma glucose level is higher, along with higher plasma insulin response, state of IR tends to be more severe.

Log (homeostasis model assessment-insulin-insulation resistance)

Log (HOMA-IR) is useful for assessment of IR. In research studies it may be appropriate to use log (HOMA-IR) instead of HOMA.

Several novel markers such as IGFBP-1, hs-CRP, adiponectin, ferritin, HbA1c, C3 complement, TNF alpha and sCD36 are now surfacing as surrogate markers of IR.[17] Other investigations for IR are fasting glucose and lipoprotein profile, hemoglobin A1c, body weight, blood pressure, and an alanine transferase test for evaluation of fatty liver.[6]

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Insulin resistance is thought to be a primary etiological factor in the development of cardiac dysfunction, higher prevalence being reported in nonischemic heart failure population. It predates the development of cardiovascular disease and independently defines a worse prognosis. Reduction in endothelial function may be a link between IR and decline in cardiovascular performance. IR may be linked to endothelial dysfunction by the number of mechanisms such as disturbance in subcellular signaling pathway and PI-3-kinase/Akt pathway.[18]

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS AND ADIPOKINES

Acanthosis nigricans patients have hyperinsulinemia and may be at greater risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.[19] The commonest underlying cause of IR is excess abdominal adipose tissue which releases increased amounts of free fatty acids which directly affect insulin signaling, diminish glucose uptake in muscle, drive exaggerated triglyceride synthesis and induce gluconeogenesis in liver. Other factors presumed to play a role in IR are tumor necrosis factor α, adiponectin, leptin, interlukin-6 and other adipokines. When β-cells fail to secrete excess insulin needed, diabetes mellitus Type 2 and coronary heart disease occur as a complication of IR.[20]

METABOLIC SYNDROME, INSULIN RESISTANCE AND ADIPOKINES

Obesity is commonly associated with type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and hypertension, coexistence of which is termed the metabolic syndrome. IR lies at the heart of the metabolic syndrome. Elevated serum triglycerides commonly associated with IR represent a valuable clinical marker of metabolic syndrome.[21]

White adipose tissue is a major site of energy storage and it has been increasingly recognized as an important endocrine organ that secretes a number of biologically active “adipokines” (leptin, adiponectin, resistin), some of which (especially resistin and adiponectin) have been shown to directly or indirectly affect insulin sensitivity through modulation of insulin signaling and the molecules involved in glucose and lipid metabolism.

Chronic state of IR is associated with secondary changes in levels of “adipokines” (decreased serum adiponectin, increased serum resistin and decreased adiponectin gene expression). Decrease in adiponectin levels by genetic and environmental factors contributes to the development of the metabolic syndrome. Adiponectin is important because of its antidiabetic and antiatherogenic effects; hence it is expected to be a novel therapeutic tool for the metabolic syndrome. The thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of antidiabetic drugs, having pleiotropic effects on cardiovascular diseases and lipid metabolism exert their effects partly through increasing levels of adiponectin. Adiponectin expression and levels in circulation are upregulated by rosiglitazone.[22]

TREATMENT OF ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS

Therapeutic approach involves treatment of underlying disease or tumor, cessation/avoidance of the inciting agent in drug-induced AN, use of topical/oral agents and cosmetic surgery.[12]

Weight loss and exercise have shown to increase insulin sensitivity and reduce insulin levels causing improvement in obesity associated AN.[23] Correction of hyperinsulinemia reduces hyperkeratotic lesions. Acipimox may be used instead of nicotinic acid to improve AN while improving lipid profile.[24]

TOPICAL TREATMENT

Retinoids

Topical retinoid is considered first-line treatment, especially for unilateral nevoid AN.[10] It is epidermopoietic and causes a reduction of the stratum corneum replacement time. It corrects hyperkeratosis and causes near complete reversion to normal state. Lahiri and Malakar in their study have reported that intermittent tretinoin application is needed to maintain improved status.[25]

Ammonium lactate and tretinoin

Retinoids affect cell growth, differentiation, and morphogenesis and alter cell cohesiveness. Lactic acid is an alpha-hydroxy acid that works as a peeling agent and also via release of desmogleins, indicating disintegration of desmosomes. Though the exact mechanism of action of the two agents is unknown, synergistic interaction is thought to play a role.[11]

Peels

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) is a superficial chemical exfoliating agent causing destruction of the epidermis with subsequent repair and rejuvenation. TCA (15%) is caustic and causes coagulation of skin proteins leading to frosting. Precipitation of proteins leads to necrosis and destruction of epidermis, followed by inflammation and activation of wound repair mechanisms. This leads to re-epithelialization with replacement of smoother skin. The advantages of TCA are that it is a stable product, hence systemic absorption and peel depth correlate with the intensity of frost and endpoint is easy to judge. TCA is safe, easily available, cheap, and easy to prepare. TCA 15% is a safe and effective therapeutic modality for AN in comparison to other topical treatments. Topical tretinoin needs frequent application for long duration (2 months) and improves hyperkeratosis, but not hyperpigmentation. Topical salicylic acid, podophyllin, urea, and calcipotriol need frequent application, while TCA peel is done in two to three sessions. Dermabrasion or alexandrite laser are expensive and may lead to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Zayed et al. have reported improvement of AN in six female patients after TCA peeling.[26]

Calcipotriol

Calcipotriol is another beneficial treatment in AN.[11,27] It inhibits keratinocyte proliferation and promotes differentiation by increasing intracellular calcium levels and cyclic GMP levels in keratinocytes. Gregoriou et al. concluded that it is safe, well-tolerated, alternative treatment for AN when an etiological treatment is not possible or necessary. Bohm et al. reported a case of mixed-type AN responding favorably to calcipotriol.[28]

Miscellaneous treatment

Other beneficial therapies (case reports) include fish oil.[11,27] 20% podophyllin in alcohol[29] (for benign AN) topical colecalciferol[30] and surgical excision.[27] Urea, salicylic acid and triple-combination depigmenting cream (tretinoin 0.05%, hydroquinone 4%, fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%) with sunscreens are other options.[24]

ORAL TREATMENT

Oral retinoids

Oral retinoids (isotretinoin, acitretin) can be effective;[30] improvement requires large doses and extended courses, and relapses are described. The mechanism of action is probably normalization of epithelial growth and differentiation.[2] Acitretin has been rarely reported for AN treatment and has showed good success in cases with syndromic and benign AN. Since acitretin has a less terminal elimination half-life and fewer lipophilic properties, its effect may be limited leading to early recurrence. Oral isotretinoin has been used successfully treat to extensive AN.[31]

Metformin and rosiglitazone

Metformin and rosiglitazone are useful in AN characterized by IR. Paula et al. observed reduction in fasting insulin levels with rosiglitazone when compared to metformin and modest improvement of skin texture with both. Duration of treatment may be related to improvement as metformin improves AN and IR if given for 6 months or more [Figure 7a and b].[23] Metformin reduces glucose production by increasing peripheral insulin responsiveness, reduces hyperinsulinemia, body weight and fat mass and improves insulin sensitivity.[30,32,33] The combined use of metformin and TZDs which increase sensitivity to insulin in peripheral muscles, also give good results.[34] The combined metformin and glimepiride (at low dose) is superior in the management of IR studied through HOMA with reduction in HOMA-IR.[35] Metformin is known to improve cardiopulmonary performance in patients with high HOMA-IR possibly by favorable effects on endothelial dysfunction.[18]

Figure 7.

(a) and (b) Improvement in acanthosis nigricans after 2 months of metformin

Cosmetic treatment

Because darkening of affected areas is common in AN, Alan Rosenbach considered the possibility that long-pulsed alexandrite laser, which was designed to target melanin in hair could improve this condition. They hypothesized that thermal heating of epidermis and dermis results in tissue remodeling and pigment reduction. They reported 95% clearance of AN of axillae after seven sessions and concluded that long-pulsed alexandrite laser can effectively and safely treat acanthosis nigricans of the axillae.[11,27,36]

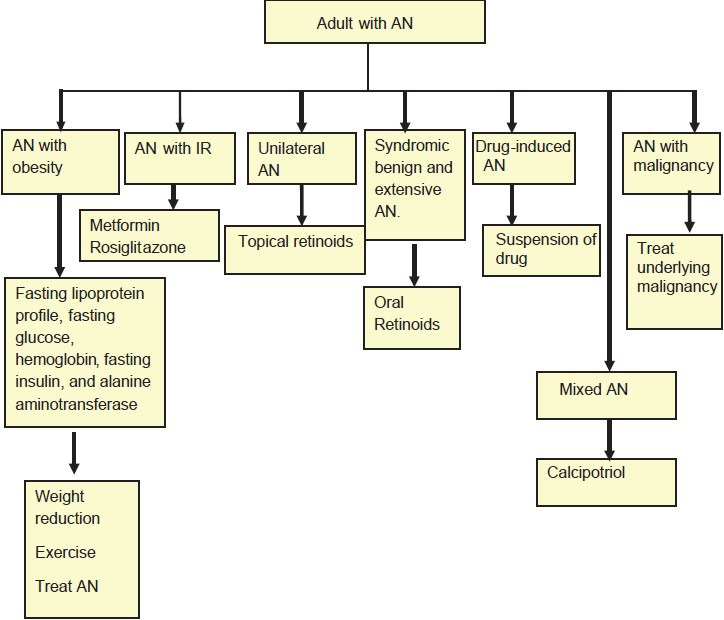

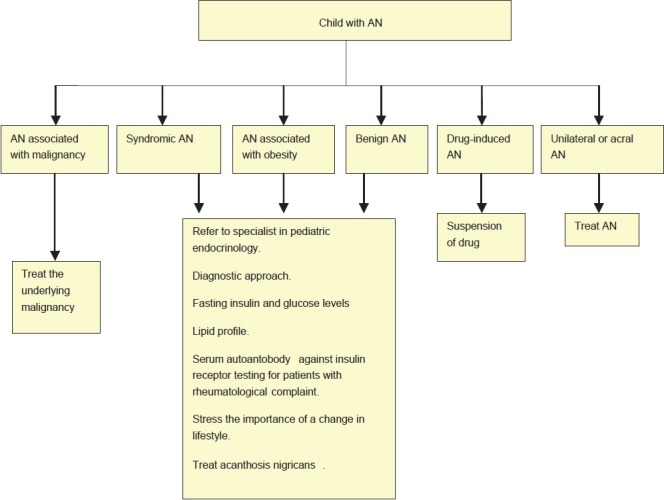

Treatment of acanthosis nigricans maligna

There is a case report of AMN regressing rapidly following treatment with cyproheptadine despite progression of metastatic disease. Rothman in 1925 suggested that both AMN and juvenile AN might be associated with some growth promoting substance in the blood causing papillary hypertrophy of skin. Therefore it was proposed that flattening of AN occurs after administration of cyproheptadine due to reduction of growth hormone released from pituitary, or from the tumor or metastasis.[37] Bonnekoh et al. successfully treated AMN associated with bronchial carcinoma with psoralen and ultraviolet A radiation therapy (patient received oral 8-methoxypsoralen and a total UVA dose of 52 J/cm2 over 18 exposures) Flow Charts 2 and 3 detail the treatment of adult and childhood AN respectively.[34]

Flow Chart 2.

Approach to AN in adult

Flow Chart 2.

Approach to AN in children

CONCLUSION

Though mainly a disease of cosmetic concern, AN can be pointer to underlying metabolic syndrome or malignancy. A thorough investigation and treatment is therefore mandatory to prevent long term consequences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke JP, Hale DE, Hazuda HP, Stern MP. A quantitative scale of acanthosis nigricans. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1655–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.10.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeong KH, Oh SJ, Chon S, Lee MH. Generalized acanthosis nigricans related to type B insulin resistance syndrome: A case report. Cutis. 2010;86:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo Y, Umegaki N, Terao M, Murota H, Kimura T, Katayama I. A case of generalized acanthosis nigricans with positive lupus erythematosus-related autoantibodies and antimicrosomal antibody: Autoimmune acanthosis nigricans? Case Rep Dermatol. 2012;4:85–91. doi: 10.1159/000337751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Safoury OS, Shaker OG, Fawzy MM. Skin tags and acanthosis nigricans in patients with hepatitis C infection in relation to insulin resistance and insulin like growth factor-1 levels. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:102–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.94275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakubovic BD, Sawires HF, Adam DN. Occult cause of paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans in a patient with known breast dcis: Case and review. Curr Oncol. 2012;19:e299–302. doi: 10.3747/co.19.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, editors. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2011. Endocrine diseases; pp. 494–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2010. p. 19. (119-21). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawatkar GU, Dogra S, Bhadada SK, Kanwar AJ. Acanthosis nigricans – An uncommon cutaneous adverse effect of a common medication: report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:553. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.113112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavithran K, Karunakaran M, Palit A. Disorders of keratinization. In: Valia RG, Ameet RV, editors. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2008. pp. 1009–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong JS, Lee JY, Yoon TY. Unilateral nevoid acanthosis nigricans with a submammary location. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:95–7. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins SP, Freemark M, Prose NS. Acanthosis nigricans: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy N, Das T, Kundu AK, Maity A. Atypical presentation of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:1058–9. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.103048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devpura S, Pattamadilok B, Syed ZU, Vemulapalli P, Henderson M, Rehse SJ, et al. Critical comparison of diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and colorimetry as dermatological diagnostic tools for acanthosis nigricans: A chemometric approach. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:1664–73. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu JF, Liang L, Dong GP, Jiang YJ, Zou CC. Obese children with benign acanthosis nigricans and insulin resistance: Analysis of 19 cases. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2004;42:917–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urrutia-Rojas X, McConathy W, Willis B, Menchaca J, Luna-Hollen M, Marshall K, et al. Abnormal glucose metabolism in Hispanic parents of children with acanthosis nigricans. ISRN Endocrinol 2011. 2011:481371. doi: 10.5402/2011/481371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne KS, Rader RK, Lastra G, Stoecker WV. Posterolateral neck texture (insulin neck): Early sign of insulin resistance. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:875–7. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh B, Saxena A. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance: A review. World J Diabetes. 2010;1:36–47. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v1.i2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cadeddu C, Nocco S, Deidda M, Cadeddu F, Bina A, Demuru P, et al. Relationship between high values of HOMA-IR and cardiovascular response to metformin. Int J Cardiol. 2012;9:302–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz AS, Goff DC, Feldman SR. Acanthosis nigricans in obese patients: Presentations and implications for prevention of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Dermatol Online J. 2000;6:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mlinar B, Marc J, Janez A, Pfeifer M. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance and associated diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;375:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grundy SM. Hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:25F–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1784–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellot-Rojas P, Posadas-Sanchez R, Caracas-Portilla N, Zamora-Gonzalez J, Cardoso-Saldaña G, Jurado-Santacruz F, et al. Comparison of metformin versus rosiglitazone in patients with acanthosis nigricans: A pilot study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:884–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puri N. A study of pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans and its clinical implications. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:678–83. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahiri K, Malakar S. Topical tretinoin in acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62:159–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zayed A, Sobhi RM, Abdel Halim DM. Using trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of acanthosis nigricans: A pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:223–5. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.674194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapoor S. Diagnosis and treatment of acanthosis nigricans. Skinmed. 2010;8:161–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregoriou S, Anyfandakis V, Kontoleon P, Christofidou E, Rigopoulos D, Kontochristopoulos G. Acanthosis nigricans associated with primary hypogonadism: Successful treatment with topical calcipotriol. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:373–5. doi: 10.1080/09546630802050506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein E. Podophyllin therapy in acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 1951;17:7. doi: 10.1038/jid.1951.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermanns-Lê T, Scheen A, Piérard GE. Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin resistance: Pathophysiology and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:199–203. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz RA. Treatment of acanthosis nigricans with oral isotretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:110–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atabek ME, Pirgon O. Use of metformin in obese adolescents with hyperinsulinemia: a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21:339–48. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2008.21.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tankova T, Koev D, Dakovska L, Kirilov G. Therapeutic approach in insulin resistance with acanthosis nigricans. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56:578–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbato MT, Criado PR, Silva AK, Averbeck E, Guerine MB, Sá NB. Association of acanthosis nigricans and skin tags with insulin resistance. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:97–104. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bermúdez-Pirela VJ, Cano C, Medina MT, Souki A, Lemus MA, Leal EM, et al. Metformin plus low-dose glimeperide significantly improves Homeostasis Model Assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA (IR)) and beta-cell function (HOMA (beta-cell)) without hyperinsulinemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Ther. 2007;14:194–202. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000249909.54047.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbach A, Ram R. Treatment of Acanthosis nigricans of the axillae using a long-pulsed (5-msec) alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1158–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenwood R, Tring FC. Treatment of malignant acanthosis nigricans with cyproheptadine. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:697–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]