INTRODUCTION

Definition, rationale and scope

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are defined as open lesions between the knee and ankle joint that occur in the presence of venous disease.[1] They are the most common cause of leg ulcers, accounting for 60-80% of them.[2] The prevalence of VLUs is between 0.18% and 1%.[3] Over the age of 65, the prevalence increases to 4%.[4] On an average 33-60% of these ulcers persist for more than 6 weeks and are therefore referred to as chronic VLUs.[5] These ulcers represent the most advanced form of chronic venous disorders like varicose veins and lipodermatosclerosis.[6]

Risk factors for development of VLUs include older age, female sex, obesity, trauma, immobility, congenital absence of veins, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), phlebitis, and factor V Leiden mutation.[7,8,9]

Poor prognostic factors[10,11]

Duration of more than 1 year - recurrence rate in these ulcers is more than 70%

Larger wounds

Fibrin in >50% of wound surface

Ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) <0.8

Chronic venous leg ulcer results in reduced mobility, significant financial implications, and poor quality of life. There are no uniform guidelines for assessment and management of this group of conditions, which is reaching epidemic proportions in the prevalence. There is a wide variation in healing and recurrence rates of these ulcers in the Indian population due to differing nutritional status, availability of medical facilities and trained medical staff to diagnose and manage such conditions. These guidelines are devised based on current available evidence to help all concerned in accurately assessing, correctly investigating and also providing appropriate treatment for this condition.

Pathophysiology

Venous hypertension

Deep vein thrombosis, perforator insufficiency, superficial and deep vein insufficiencies, arteriovenous fistulas and calf muscle pump insufficiencies lead to increased pressure in the distal veins of the leg and finally venous hypertension.

Fibrin cuff theory

Fibrin gets excessively deposited around capillary beds leading to elevated intravascular pressure. This causes enlargement of endothelial pores resulting in further increased fibrinogen deposition in the interstitium. The “fibrin cuff” which surrounds the capillaries in the dermis decreases oxygen permeability 20-fold. This permeability barrier inhibits diffusion of oxygen and other nutrients, leading to tissue hypoxia causing impaired wound healing.[12]

Inflammatory trap theory

Various growth factors and inflammatory cells, which get trapped in the fibrin cuff promote severe uncontrolled inflammation in surrounding tissue preventing proper regeneration of wounds.[13] Leukocytes get trapped in capillaries, releasing proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen metabolites, which cause endothelial damage. These injured capillaries become increasingly permeable to various macromolecules, accentuating fibrin deposition. Occlusion by leukocytes also causes local ischemia thereby increasing tissue hypoxia and reperfusion damage.

Dysregulation of various cytokines

Dysregulation of various pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TGF-β and matrix metalloproteinases lead to chronicity of the ulcers.[14,15]

Miscellaneous

Thrombophilic conditions like factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin mutations, deficiency of antithrombin, presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, protein C and S deficiencies and hyperhomocysteinemia are also implicated.[16]

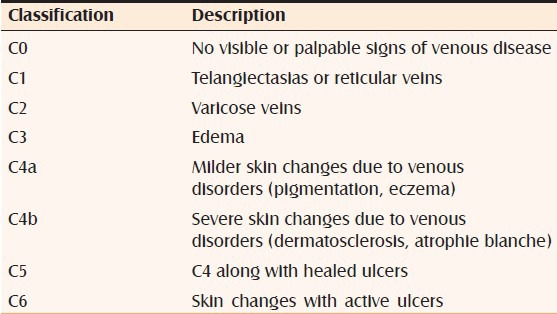

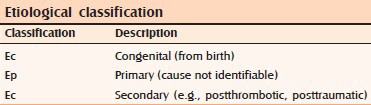

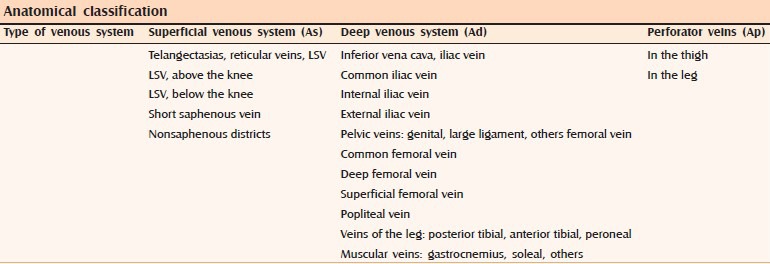

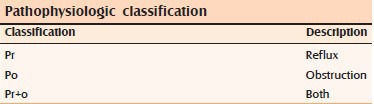

CLASSIFICATION OF CHRONIC VENOUS INSUFFICIENCY

The classification and staging of chronic venous insufficiency (clinical severity) can be measured by a scoring system called clinical manifestations, etiological factors, anatomical distribution, and pathophysiological conditions[17,18] (evidence Level D) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Classification of venous ulcers

Assessment and stepwise approach to diagnosis of VLU.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

1. Rule out arterial disease, which are indicated by:[19]

History of intermittent claudication, cardiovascular disease and stroke

Absence of pedal pulses

Abnormal blood pressure (BP): It gives clues to the presence of any cardiovascular disease.

It is very important to rule out arterial etiology as application of compression in such cases can cause severe damage[20,21] (evidence Level D).

2. Obtain clues from history suggesting venous etiology[22] (evidence Level D)

History of previous or current DVT

Family history of leg ulcers

Varicose veins or its treatment

History of phlebitis

Surgery, trauma or fractures of the affected leg, which can damage the valves

Chest pain, hemoptysis or pulmonary embolism

Occupations of prolonged standing or sitting

Obesity

Multiple pregnancies

Aching pain in the lower limbs.

3. Clinical examination to confirm the diagnosis of venous ulcer

Examination of ulcer

Location: Anterior to medial malleolus, pretibial area, lower third of leg (gaiter region)[23] (evidence Level C)

Measurement of size: Serial measurement of surface area of ulcer is a reliable index of prognosis and healing. Measurements of length, width and depth of ulcer with two maximum perpendicular axes are important. Disposable ruler, photography, acetate tracings and computerized calculation (planimetry) following digital photography are the methods which are used in measurement. Measuring the ulcers help in identifying patients not responding to conventional therapy and those requiring alternative therapy[24] (evidence Level C)

Characteristics of the ulcer: Shallow depth, irregular shaped edges with well-defined margins

Amount and type of exudates: Yellow-white in color

Appearance of ulcer bed: Presence of ruddy viable granulation tissue. Thick slough or eschar indicates arterial insufficiency

Signs of infection: Cellulitis, delayed healing despite appropriate compression therapy, increase in local skin temperature, increase in ulcer pain or change in nature of pain, newly formed ulcers within inflamed margins of preexisting ulcers, wound bed extension within inflamed margins, discoloration (esp. dull, dark brick-red), friable granulation tissue that bleeds easily, increase in exudate viscosity, increase in exudate volume, malodor, new-onset dusky wound hue, sudden appearance or increase in an amount of slough, sudden appearance of necrotic black spots and ulcer enlargement[25] (evidence Level D). Take a swab only if these signs are present

Ulcer odor

Pain associated with ulcer: Pain may be absent, mild or extreme. Pain is more at the end of the day and usually relieved by elevation of the leg.

Periulcer area

Capillary leaking causing edema leading to maceration, pruritus and scaling. Associated warmth and pruritus.

Associated changes in the leg

Firm (“brawny”) edema

Hemosiderin deposit (reddish brown pigmentation)

Lipodermatosclerosis

Evidence of healed ulcers

Dilated and tortuous superficial veins

Limb may be warm

Atrophie blanche

Eczema

Altered shape – inverted “champagne bottle”

Ankle flare.

4. Regular documentation to compare results before and after treatment and progression with time

5. Assess comorbidities like obesity, malnutrition, intravenous drug use and coexisting medical conditions prior to surgery. Reduced calorie and protein intake hampers ulcer healing[26] (evidence Level D)

6. Rule out complications including severe infections, osteomyelitis and malignant changes[7] (evidence Level D).

7. If no improvement after 12 weeks or in case of recurrence or no response to treatment after 6 weeks: Reassess

Risk factors for nonhealing - Increased wound size and duration, history of venous stripping or ligation, history of hip or knee replacement, ankle-brachial index < 0.8, >50% of wound covered in fibrin and undermined wound margin

Accuracy of etiology

Rule out allergic contact dermatitis to medications and differentiate from venous eczema. Do a patch test in all cases of venous ulcers with eczema. The common sensitizers are lanolin, topical antibiotics (gentamycin, neomycin, bacitracin), antiseptics, preservatives, emulsifiers, resins and latex.[27,28,29,30,31] (evidence level C). Positive patch tests in these ulcers range from 40% to 82.5%.[27,32,33,34] (evidence Level B)

Any new comorbidities?

Think of biopsy (in case of atypical and nonhealing ulcers) - to rule out malignancy, systemic disorders, collagen vascular disorders and vasculitis[35] (evidence Level D)

Take bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal cultures

Is the treatment appropriate?

Is patient compliant with treatment?

INVESTIGATIONS

Noninvasive

-

ABPI: This is a noninvasive test using the handheld Doppler ultrasound which identifies peripheral arterial disease in the leg. Systolic BP is measured at the brachial artery and at the ankle level.

ABPI = highest systolic foot pressure (dorsalis pedis/posterior tibial artery)/highest systolic brachial BP

Nylon monofilament can be used as a simple screening test to rule out sensory neuropathy[42] (evidence Level C)

Duplex ultrasound: It is a noninvasive test which combines ultrasound with Doppler ultrasonography. Blood flow through arteries and veins can be investigated to reveal any obstructions. It allows direct visualization of veins, identifies flow through valves and can map both superficial and deep veins[43] (evidence Level C)

Photoplethysmography: This is a noninvasive test which measures venous refill time. A probe placed on the skin surface just above the ankle is used for the detection. The patient is instructed to perform calf muscle pump exercises for brief periods followed by the rest. The probe actually measures the reduction in skin blood flow following exercise. This determines the efficiency of the calf muscle pump and the presence of any abnormal venous reflux. Patients with problems in superficial or deep veins usually have poor emptying of the veins and abnormally rapid refilling (<25 s)[44] (evidence Level C)

Pulse oximetry: This is another noninvasive test which measures the red and infrared light absorption of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in a digit. Oxygenated hemoglobin absorbs more infrared light and allows more red light to pass through a digit. Deoxygenated hemoglobin absorbs more red light and allows more infrared light to pass through the digit. However, there is insufficient evidence to recommend this investigation as a primary diagnostic tool[45,46] (evidence Level C)

Toe brachial pressure index (TBPI): Noninvasive test that measures arterial perfusion in toes and feet. A toe cuff is applied to hallux and pressure is divided by the highest brachial systolic pressure, which is the best estimate of central systolic BP. TBPI identifies incompressible calcified arteries in diabetics and renal disease patients[47]

Transcutaneous oxygen: Measures amount of oxygen reaching the skin through blood circulation. Presently, insufficient evidence to recommend as primary diagnostic test.

Invasive

-

Biochemical tests

- Blood glucose - To rule out diabetes

- Hemoglobin - To rule out hematological disorders

- Urea and electrolytes

- Serum albumin, transferrin - To rule out nutritional deficiencies

- Lipids

- Rheumatoid factor

- Auto antibodies

- White blood cell count

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- C-reactive protein.

Liver function testsk

Activated protein C: Detected in 25% venous ulcers and 50% of recurrent venous thromboses patients[48] (evidence level D)

Microbiology: Bacterial wound swab when ulcer shows clinical signs of infection like cellulitis, pyrexia, increased pain, rapid extension of the area of ulceration, malodor and increased exudates[49] (evidence Level C)

Histopathology: Wound biopsy only if malignancy or other etiology is suspected.

SUMMARY [EVIDENCE LEVEL C]

The prevalence of VLUs is on the increase with chronic venous insufficiency being the main culprit. A detailed accurate assessment of leg ulcer in patients is essential to ensure starting of timely and appropriate treatment. It should be an ongoing continuous assessment as signs and symptoms can rapidly change thereby requiring progressive evaluation. Good and accurate quality patient assessment will save time and cost by an enforcement of appropriate treatment regimens.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) Edinburgh: SIGN; 1998. The Care of Patients with Chronic Leg Ulcer. Guideline 26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Meara S, Al-Kurdi D, Ovington LG. Antibiotics and antiseptics for venous leg ulcers. [Last assessed on 2013 Dec 20];Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 14 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003557.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornwall JV, Doré CJ, Lewis JD. Leg ulcers: Epidemiology and aetiology. Br J Surg. 1986;73:693–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callam MJ, Ruckley CV, Harper DR, Dale JJ. Chronic ulceration of the leg: Extent of the problem and provision of care. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:1855–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6485.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briggs M, Flemming K. Living with leg ulceration: A synthesis of qualitative research. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59:319–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowkes FG, Evans CJ, Lee AJ. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology. 2001;52:S5–15. doi: 10.1177/0003319701052001S02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbade LP, Lastória S. Venous ulcer: Epidemiology, physiopathology, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:449–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott TE, LaMorte WW, Gorin DR, Menzoian JO. Risk factors for chronic venous insufficiency: A dual case-control study. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:622–8. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etufugh CN, Phillips TJ. Venous ulcers. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruckley CV. Socioeconomic impact of chronic venous insufficiency and leg ulcers. Angiology. 1997;48:67–9. doi: 10.1177/000331979704800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margolis DJ, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Risk factors associated with the failure of a venous leg ulcer to heal. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:920–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.8.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnand KG, Whimster I, Naidoo A, Browse NL. Pericapillary fibrin in the ulcer-bearing skin of the leg: The cause of lipodermatosclerosis and venous ulceration. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:1071–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6348.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falanga V, Eaglstein WH. The “trap” hypothesis of venous ulceration. Lancet. 1993;341:1006–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91085-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendez MV, Raffetto JD, Phillips T, Menzoian JO, Park HY. The proliferative capacity of neonatal skin fibroblasts is reduced after exposure to venous ulcer wound fluid: A potential mechanism for senescence in venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:734–43. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higley HR, Ksander GA, Gerhardt CO, Falanga V. Extravasation of macromolecules and possible trapping of transforming growth factor-beta in venous ulceration. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb08629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norgauer J, Hildenbrand T, Idzko M, Panther E, Bandemir E, Hartmann M, et al. Elevated expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (CD147) and membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases in venous leg ulcers. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1180–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.05025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kistner RL, Eklof B, Masuda EM. Diagnosis of chronic venous disease of the lower extremities: The “CEAP” classification. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:338–45. doi: 10.4065/71.4.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, Carpentier PH, Gloviczki P, Kistner RL, et al. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: Consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphreys ML, Stewart AH, Gohel MS, Taylor M, Whyman MR, Poskitt KR. Management of mixed arterial and venous leg ulcers. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1104–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Edinburgh: SIGN; 2010. Management of Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers. A National Clinical Guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Recommendations. London: RCN; 2006. Royal College of Nursing Centre for Evidence Based Nursing. Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Nursing Management of Patients with Venous Leg Ulcers. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carville K. Osborne Park, WA: Silver Chain Nursing Association; 2005. Wound Care Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelzén O, Bergqvist D, Lindhagen A. Venous and non-venous leg ulcers: Clinical history and appearance in a population study. Br J Surg. 1994;81:182–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stacey MC, Burnand KG, Layer GT, Pattison M, Browse NL. Measurement of the healing of venous ulcers. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61:844–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Wound Management Association. London: MEP Ltd; 2005. Position document. Identifying Criteria for Wound Infection. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wipke-Tevis DD, Stotts NA. Nutrition, tissue oxygenation, and healing of venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Nurs. 1998;16:48–56. doi: 10.1016/s1062-0303(98)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson CL, Cameron J, Powell SM, Cherry G, Ryan TJ. High incidence of contact dermatitis in leg-ulcer patients – Implications for management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:250–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1991.tb00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaki I, Shall L, Dalziel KL. Bacitracin: A significant sensitizer in legulcer patients? Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:92–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angelini G, Rantuccio F, Meneghini CL. Contact dermatitis in patients with leg ulcers. Contact Dermatitis. 1975;1:81–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1975.tb05332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fräki JE, Peltonen L, Hopsu-Havu VK. Allergy to various components of topical preparations in stasis dermatitis and leg ulcer. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:97–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1979.tb04806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulozik M, Powell SM, Cherry G, Ryan TJ. Contact sensitivity in community-based leg ulcer patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:82–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1988.tb00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallenkemper G, Rabe E, Bauer R. Contact sensitization in chronic venous insufficiency: Modern wound dressings. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38:274–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichert-Pénétrat S, Barbaud A, Weber M, Schmutz JL. Leg ulcers. Allergologic studies of 359 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsarou-Katsari A, Armenaka M, Katsenis K, Papageorgiou M, Katsambas A, Bareltzides A. Contact allergens in patients with leg ulcers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang D, Morrison BD, Vandongen YK, Singh A, Stacey MC. Malignancy in chronic leg ulcers. Med J Aust. 1996;164:718–20. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Qaisi M, Nott DM, King DH, Kaddoura S. Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI): An update for practitioners. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:833–41. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fowkes FG, Housley E, Macintyre CC, Prescott RJ, Ruckley CV. Variability of ankle and brachial systolic pressures in the measurement of atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988;42:128–33. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2006. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 20]. Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease. SIGN Guideline No. 89. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign89.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caruana MF, Bradbury AW, Adam DJ. The validity, reliability, reproducibility and extended utility of ankle to brachial pressure index in current vascular surgical practice. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowkes FG. The measurement of atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease in epidemiological surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 1988;17:248–54. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Male S, Coull A, Murphy-Black T. Preliminary study to investigate the normal range of Ankle Brachial Pressure Index in young adults. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1878–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caputo GM, Cavanagh PR, Ulbrecht JS, Gibbons GW, Karchmer AW. Assessment and management of foot disease in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:854–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dugdale D. Medline Plus. Duplex Ultrasound. 2010. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 20]. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003433.htm .

- 44.Dodds S. ABC of Vascular Disease: Photoplethysmography (PPG) 2001. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.simondodds.com/

- 45.Bianchi J, Douglas WS, Dawe RS, Lucke TW, Loney M, McEvoy M, et al. Pulse oximetry: A new tool to assess patients with leg ulcers. J Wound Care. 2000;9:109–12. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2000.9.3.26267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bianchi J, Zamiri M, Loney M, McIntosh H, Dawe RS, Douglas WS. Pulse oximetry index: A simple arterial assessment for patients with venous disease. (256-8).J Wound Care. 2008;17:253–4. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.6.29585. 260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses Society. Toe brachial index: Best practice for clinicians. 2008. [Last cited on 2010 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.wocn.org .

- 48.Peus D, Heit JA, Pittelkow MR. Activated protein C resistance caused by factor V gene mutation: Common coagulation defect in chronic venous leg ulcers? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:616–20. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansson C, Hoborn J, Möller A, Swanbeck G. The microbial flora in venous leg ulcers without clinical signs of infection. Repeated culture using a validated standardised microbiological technique. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:24–30. doi: 10.2340/00015555752430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]