Abstract

Introduction: There are nearly 3 million Syrian refugees, with more than 1 million in Lebanon. We combined quantitative and qualitative methods to determine cesarean section (CS) rates among Syrian refugees accessing care through United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)-contracted hospitals in Lebanon and possible driving factors.

Methods: We analyzed hospital admission data from UNHCR’s main partners from December 2012/January 1, 2013, to June 30, 2013. We collected qualitative data in a subset of hospitals through semi-structured informant interviews.

Results: Deliveries accounted for almost 50 percent of hospitalizations. The average CS rate was 35 percent of 6,366 deliveries. Women expressed strong preference for female providers. Clinicians observed that refugees had high incidence of birth and health complications diagnosed at delivery time that often required emergent CS.

Discussion: CS rates are high among Syrian refugee women in Lebanon. Limited access and utilization of antenatal care, privatized health care, and male obstetrical providers may be important drivers that need to be addressed.

Keywords: refugee, Lebanon, cesarean section, Syrian crisis, humanitarian emergency

Introduction

The cesarean section (CS) is one of the most commonly performed surgeries. Since 1985, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended maintaining a CS rate between 5 and 15 percent [1], although the optimal rate remains controversial. While many women and health care providers believe the surgery does not have serious risks, research suggests otherwise [2]; unnecessary CS do not bring health gains such as faster recovery or better care [3], but rather adverse outcomes such as antibiotic treatment, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, blood transfusion, hysterectomy, and even death [4,5]. Unfortunately, there is a growing trend worldwide of CS being performed without medical indication. The Arab region is no exception, with a stark under-utilization of CS in resource-poor countries and high rates in more developed ones [6]. Across Arab countries, Egypt has the highest CS rate of 26.2 percent, with Mauritania the lowest at 5.3 percent [7].

Currently, the CS rate is approximately 21.1 percent for the most developed areas globally, 14.3 percent for the lesser developed areas, and 2 percent for the least developed regions [8]. According to the 2010 World Health Report [9], there were approximately 18.5 million CS performed annually worldwide; 73 percent (13.5 million) performed in the 69 countries with CS rates >15 percent, where 37.5 percent (48.4 millions) of the total number of births occur. Countries with <10 percent CS rates are considered to show underuse of CS, while countries with >15 percent are considered to have overuse [1]. Using these criteria, in 2008 (latest available data), 3.18 million additional CS were needed and 6.20 million unnecessary CS were performed; the cost of the excess CS averaged US$2.32 billion [9]. This overuse commands a disproportionate share of global economic resources and can be a costly load on public-sector services.

In times of conflict, seeking and providing maternal care is challenging. Services can be interrupted or reduced, logistical access to facilities difficult, and health care workers can be targeted [10]. These factors may contribute to difficulty in adherence to well-established clinical standards [11]. There is limited literature on CS in humanitarian settings. During the Balkans war (1992-1995), it was noted that the rates of CS and post-term deliveries dropped, while there were more spontaneous abortions and vaginal deliveries following CS [12,13]. An article in 2006 about the Lebanese conflict and maternal care showed that the use of antenatal care (ANC) sharply declined among displaced populations, with issues in accessibility and availability of services being the main determinants of that decline [11]. Another study showed that during the armed conflict in Northern Sri Lanka, the CS rate among the internally displaced was 44.3 percent, despite adequate ANC attendance [14]. This article aims to determine the CS rate among the Syrian refugee population accessing care through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)-contracted hospitals in Lebanon and the possible driving factors behind those rates.

The Syrian Refugee Crisis: Background and UNHCR’s Policy on Deliveries

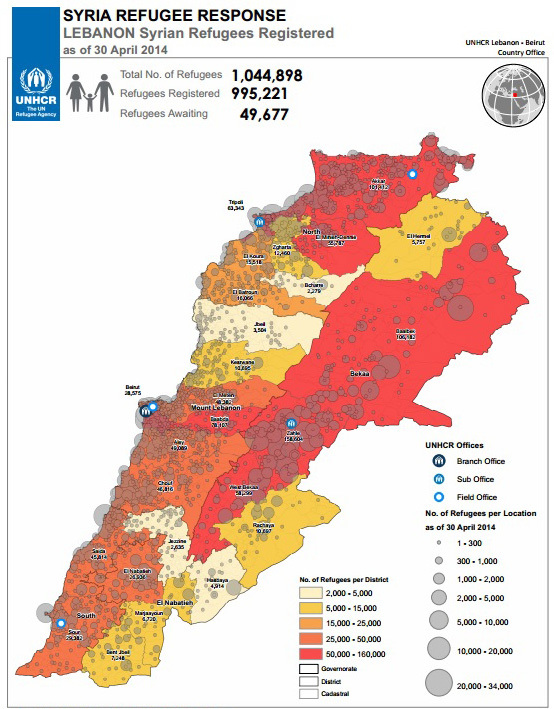

The Syrian conflict began more than 3 years ago and has displaced more than 2.7 million refugees into neighboring countries. Lebanon is the smallest of all hosting countries, yet provides asylum for the largest number of Syrian refugees (more than 1 million). With a 2012 population estimated at 4.425 million and a gross domestic product of $42.95 billion, Lebanon is today classified by the World Bank as an upper middle income country [15]. The Lebanese government estimates there are more than 1 million refugees in Lebanon today. According to UNHCR’s website, there were a total of 1,067,151 refugees in Lebanon as of May 15, 2014; 1,014,530 of them were registered and the rest awaiting registration [16]. Geographically, refugees are concentrated in the Bekaa, the North, and the Beirut area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The boundaries, names, and designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement of the United Nations or UNHCR. All data used were the best available at the time of map production. Refugee population and location data by UNHCR as of 30 April 2014. GIS and Mapping by UNHCR Lebanon. Map used with permission by UNHCR Lebanon, Beirut Country Office.

Registered Syrian refugees are entitled to a specific level of health care coverage as outlined in UNHCR’s Standard Operating Procedures for medical services. Mobile registration units exist for non-registered refugees to become registered, even for those in hospital. Pregnancy, including delivery, falls within the life-saving procedures and is therefore covered by UNHCR at 75 percent of the total cost. For deliveries, packages have been negotiated with hospitals for natural vaginal deliveries (NVDs) and CS. For NVDs, registered refugees pay a maximum of $50 per incidence, depending on hospital class. CS have been contracted to stay up to 3 days in the hospital post-delivery and an NVD for 1 day.

C-Section Rates for Lebanon and Syria

It is difficult to obtain systematic and standardized data about CS rates in Arab countries because they often lack functioning national registration systems. According to a 2009 overview of CS in Arab countries, Lebanese and Syrian women >35 years had 7 to 8 percent higher rates of CS than women between 15 and 34 years [7]. High levels of education (secondary or higher) were positively associated with CS (Lebanon: 20.1 percent vs. 14.9 percent). According to the WHO’s 2010 World Health Report, Lebanon’s CS rate (from the National Perinatal Survey of 1999/2000) was 23.3 percent, with 5,478 estimated unnecessary CS costing approximately US$2.4 million [8,9]. Another report assessing hospital-based deliveries estimated the CS rate at 18 percent in 2000 [7]. However, there is much in-country variation; some hospitals in the Beirut area have reported CS rates as high as 35 percent [17]. Syria’s CS rates have reportedly experienced a dramatic increase since 2002, when it was reported at 15 percent [7,18]. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) now reports Syria’s CS rate in 2013 to be 45 percent, up from 29 percent [19], an increase most likely related to the crisis. However, these data must be interpreted cautiously as it was not obtained by a rigorous study.

Methods

We combined quantitative and qualitative methods to address the overall goals of determining the CS rate among the Syrian refugee population accessing care through UNHCR-contracted hospitals in Lebanon as well as the possible driving factors behind those rates. For the quantitative aspect of the analysis, we analyzed data previously collected by UNHCR’s three main health partners — the International Medical Corps (IMC) for the Bekaa and North regions, Makhzoumi Foundation (MF) for Beirut and Mount Lebanon regions, and Caritas Labor Migrant Center (CLMS) for the South region — on Syrian refugees’ overall hospital admissions. For the Bekaa/North and Beirut/Mount Lebanon regions, data were collected from January 1 to June 30, 2013. For the South region, data were collected from December 12, 2012, to June 30, 2013. All hospitals used by UNHCR’s partners listed above were included. The data was then filtered to include all admissions and diagnoses where “Intervention = Normal Delivery” or “Intervention = Cesarean Section” were the outcomes of interest. Excluded from this analysis were abortions and dilation and curettages or any other form of obstetric surgery. Using this filter, the data analysis was performed on 6,366 deliveries.

We collected qualitative data through the administration of semi-structured in-depth informant interviews with a targeted sample of medical providers (medical doctors and midwives), hospital administrators, and women who gave birth by CS to aid in the interpretation of the results of the quantitative part of the survey. For this qualitative part of the research, the hospitals were selected according to the following criteria: a) contracted by UNHCR to serve Syrian refugee women; b) comprised most of the deliveries in their category (private/public) for the area we surveyed; and c) a mixture of public and private hospitals. Data were then compiled and sorted to identify recurring themes. Interviews were conducted using three trained surveyors and a convenience sample of 37 purposefully selected informants: eight hospital administrators, six medical doctors, 12 midwives, and 11 patients. All medical doctors interviewed were Medical Directors of the maternity units, and all were men but one. All midwives were women and working in the delivery area of the hospitals. Data were then compiled and sorted to identify recurring themes.

Data collection was achieved through a voluntary in-depth interview using a semi-structured questionnaire as a supporting guide. Verbal consent was obtained from all participants after surveyors explained the project’s goals and what the interviews were about. Three individual questionnaires were designed for: 1) administration staff; 2) medical providers; and 3) patients (Appendix). All were reviewed and piloted internally for content relevance. Questionnaires were used as guides when conducting the interview and could be filled in during or after the interviews were completed. Interviews with beneficiaries were conducted in Arabic using a UNHCR translator, then transcribed into English if needed. Most questions related to women’s past obstetric history, understanding of the procedure, as well as provider preference. When possible, women with first-time CS were interviewed. The hospital administration questionnaire contained six questions and covered areas related to human resources, procedure costs, and hospital data. The medical provider questionnaire contained 14 questions, six of them specific to midwives. It covered topics such as provider perspective on the procedure, perceptions of delivery preferences for Syrian and Lebanese women, and commonly observed delivery complications, as well as length of hospital stay after delivery. The patient questionnaire contained 22 questions and was administered to women who were still in the hospital and had delivered by CS. Topics that were covered addressed past obstetric history, provider preference (male/female), understanding of procedure, labor experience and timing, and ANC history. Personnel surveyed by region and type of hospital are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Personnel surveyed by region and type of hospital (Bekaa and Beirut/Mt Lebanon).

| Public/Private | Regional Location | Personnel Surveyed |

| Public | Beirut/Mt Lebanon | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife; Beneficiary (patient) |

| Private | Beirut/Mt Lebanon | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife |

| Private | Beirut/Mt Lebanon | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife; Beneficiary |

| Public | Beirut/Mt Lebanon | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife; Beneficiary |

| Public | Bekaa | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife; Beneficiary |

| Private | Bekaa | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife; Beneficiary |

| Private | Bekaa | Hospital admin; MD; Midwife |

This work was reviewed by the University of Washington’s Human Subjects Division, which deemed it a quality improvement activity/program evaluation work. As such, “the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects do not apply, and there is no requirement under these regulations for such activities to undergo review by an IRB.”

Results

Quantitative

Between December 12, 2012 (South Region) and January 1, 2013 (all other regions) to June 30, 2013, of the 14,546 admissions recorded in all of UNHCR-contracted hospitals, 6,366 (44 percent) deliveries were recorded (Table 2). Thirty-four percent of all deliveries occurred in Bekaa, followed by 29 percent in the North, 22 percent in Beirut and Mount Lebanon, and 15 percent in the South. The average CS rate was 35 percent for all deliveries for all regions, with the Bekaa having the highest at 41 percent, compared to 31 to 34 percent in the other regions.

Table 2. Hospital deliveries for Syrian refugee women by region in Lebanon among UNHCR partners, December 12 2012/January 1 2013 to June 2013.

| Bekaa | |||||

| (Jan 1 2013-June 30 2013) | # hospitals | NVDs | CS | Total Deliveries | %CS |

| Private hospital | 7 | 1156 | 785 | 1941 | 40.4% |

| Public hospital | 2 | 116 | 108 | 224 | 48.2% |

| Total: | 9 | 1272 | 893 | 2165 | 41.2% |

| North | |||||

| (Jan 1 2013-June 30 2013) | # hospitals | NVDs | CS | Total Deliveries | %CS |

| Private hospital | 5 | 757 | 321 | 1078 | 29.7% |

| Public hospital | 1 | 489 | 267 | 756 | 35.3% |

| Total: | 6 | 1246 | 588 | 1834 | 31.9% |

| Beirut/Mt Lebanon | |||||

| (Jan 1 2013-June 30 2013) | # hospitals | NVDs | CS | Total Deliveries | %CS |

| Private hospital | 10 | 284 | 107 | 391 | 27.3% |

| Public hospital | 4 | 685 | 325 | 1010 | 31.1% |

| Total: | 14 | 969 | 432 | 1401 | 30.8% |

| South | |||||

| (Dec 12 2012-Jun 30 2013) | # hospitals | NVDs | CS | Total Deliveries | %CS |

| Private hospital | 7 | 152 | 114 | 266 | 42.8% |

| Public hospital | 4 | 487 | 213 | 700 | 30.4% |

| Total: | 11 | 639 | 327 | 966 | 33.8% |

| Total in All Regions: | 40 | 4126 | 2240 | 6366 | 35.30% |

From the data collected, public hospitals appeared to have higher rates of CS compared to private hospitals in all regions except the South. In the Bekaa, 90 percent of deliveries occurred in private hospitals, with 66 percent in one single private hospital. The other regions had fewer deliveries in private hospitals (North, 58 percent; Beirut/Mt Lebanon, 26 percent; and South, 25 percent). In Beirut/Mt Lebanon, 63 percent of all deliveries took place in one single public hospital.

Of the 6,366 births paid for by UNHCR between January and June 2013, an estimated cost of US$1.4 million was spent on CS (2,240 procedures) and US$1.4 million for the 4,126 natural vaginal deliveries.

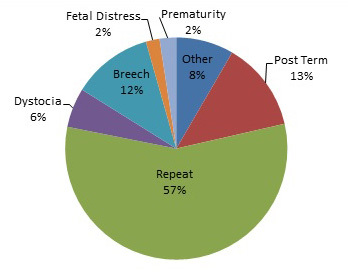

There were limited data as to the reasons why CS were carried out among the 2,240 women who had the procedure. We were able to document the reason among 453 of 1,803 (25 percent) women who had CS in the Bekaa, North and South regions; no information was available in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. The main reason for having a CS was a “repeat CS” (57 percent), with several cases accounting for the woman’s third or fourth CS. The second most common reason was “post-term” (13 percent), followed by “breech presentation” (12 percent) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reasons for cesarean sections among Syrian refugees in all regions in Lebanon, December 12, 2012/January 1, 2013 to June 2013 (N = 453).

Qualitative

Of the seven facilities where we conducted interviews, two were public hospitals and five were private hospitals. Nine women in hospital at the time of the interview discussed their experiences and understanding regarding their CS. None of the nine women interviewed had a planned CS. When asked whether they understood and agreed with the decision for a CS, all women but one said they did. That woman had an umbilical cord prolapse, a clear indication for CS. Yet she initially refused it and insisted on the NVD. It took “a lot of discussion” with the midwife to convince the woman about the necessity of the procedure, stated the doctor. Four of the nine women had no ANC visits, and two had the recommended >4 visits. The majority expressed a strong preference for female providers, and most preferred a midwife over a male physician. Only one of the seven hospitals visited had a majority of female health care providers for deliveries. Seven of the nine CS were performed by male health care providers. In separate interviews conducted with an additional 16 pregnant women waiting at registration centers or in informal tented settlements, eight reported no ANC visits, six reported one to two ANC visits, two reported three to four visits, and none reported >4 visits.

The Syrian women interviewed stated that they usually insisted on having a NVD, even against medical advice, because it is an act mostly performed by the midwives and under supervision of a medical doctor. They often resist, and sometimes refuse, to have male providers for the delivery. Of the 18 clinicians interviewed, almost all observed that Syrian refugee patients had a high incidence of birth and health complications diagnosed only at delivery time that often required emergent CS due to various diagnoses, including placenta previa, oligohydramnios, meconium in amniotic fluid, pre-eclampsia, and eclampsia. They attributed this to many Syrian women never having visited a health care provider during their pregnancy.

“Many women come in the second stage of labor to the hospital, with untreated pre-eclampsia, or meconium in the amniotic fluid.”

“Syrian women don’t know about complications. Even if they have very noticeable edema, they will not go to the doctor.”

The general manager at a private hospital in the Bekaa stated that the number of deliveries has increased and that Syrian refugees composed 85 percent of those deliveries. He also noted that NICU admissions were dominated by Syrian children. Managers and health care providers at other hospitals reported being overwhelmed with the demand for deliveries and NICU admissions by Syrian refugees. Some stated that the demand exceeded the capacity of the hospital, and non-UNHCR contracted hospitals had to be contacted to provide care for some pregnant women. As one hospital general manager stated, “You can’t grow as fast as the problem is growing.”

No hospital provider admitted to providing CS on demand. Two hospital workers said that if the woman and her husband really wanted it, they would do a CS after counseling the woman on the risks and benefits.

“With Syrian women, there are more C-sections even though they don’t want a C-section. With Lebanese women, there are less C-sections, but women sometimes request it. And if after discussion with the provider they still want it, we do it.”

They were all very clear that Syrian women never ask for a CS and strongly prefer a NVD, which is cheaper for them, has a quicker recovery, and a faster discharge. “Syrian women hate C-sections,” said a midwife. Syrian women, it was noted by all health care workers, had a very high rate of repeat CS (up to nine previous CS were observed), and they often came to the hospital with no previous ANC visits, leading to births with complications that resulted in a CS. Some providers explained the high rate of CS by directly linking it to the effects of the war in Syria, explaining that women want to plan their deliveries for safety reasons, drawing a parallel to the times when Lebanon was at war.

Discussion

Deliveries were the biggest reason for admission to hospitals for Syrian refugees from December 12, 2012/January 1, 2013, to June 30, 2013 in UNHCR-contracted hospitals that provided obstetrical care. Of these deliveries, 65 percent were NVD and 35 percent were CS; this proportion is significantly higher than the WHO recommended CS rate of between 5 and 15 percent. CS rates were not uniform among regions and in hospital types in Lebanon. The Bekaa had the highest CS rate at 41 percent, compared to 31 to 34 percent in the other regions. Public hospitals had higher rates of CS compared with private hospitals in all regions except the South. The demand on the existing public and private hospitals for delivery of obstetrical services has rapidly increased due to the Syrian refugee influx and, in some cases, exceeded existing capacity.

Much has been written about Lebanon’s high rate of CS and the atmosphere that exists to encourage its use. Lebanon’s over-medicalized birth process, which often unnecessarily intervenes with the natural process of labor, and the high rates of CS can be related to its health care system that is dominated by the private sector, limited of physician accountability, private health insurance system, limited role for midwives, and women’s misunderstanding of the CS procedure and its safety [6,20-22]. Our results are similar to another study that documented high CS rates due in part to primiparity and obstetric complications [23]; however, we did not collect women’s ages and thus could not correlate high maternal age as did this study.

In the same study, insurance coverage in the Beirut/Mount Lebanon area was also a factor in the CS rate. This area has a population with higher socio-economic background and a more highly developed medical infrastructure than the rest of Lebanon. Another study in greater Beirut assessed the predictors for nulliparous women of having a CS at a hospital with CS rates within the WHO recommendations of 5 to 15 percent (control hospitals) to the CS predictors at eight other hospitals with CS rates (25.2 percent to 42.2 percent) well above WHO’s recommendation. The main differences for having higher rates of CS were increased odds of a male provider, higher socioeconomic status of the patient, and having private or public health insurance as opposed to “unspecified” mode of payment; the latter comprised women of a lower socioeconomic background and education at the study hospitals. All women at the control hospital with lower CS rates had their labor attended by a midwife [24]. Since UNHCR pays for all or most of the CS for Syrian refugee women at UNHCR-contracted hospitals, such financial guarantees may increase number of CS doctors perform. This factor would be in line with the studies mentioned above [23,24].

In Syria, a large study examining women’s preferences for birth place and attendant type showed an overall preference to deliver in a hospital setting (65.8 percent), with most preferring their provider to be a doctor rather than a midwife (60.4 percent vs. 21.2 percent) [6]. Over 85 percent of the interviewees preferred their provider to be a female [25]. Historically for Syria, 87.7 percent of women had at least one ANC visit during their pregnancy in 2009, and 64 percent had at least 4 ANC visits (68 percent in urban areas, 59 percent in rural areas) [26]. According to the World Bank, 96 percent had a birth attended by skilled health personnel [27]. The qualitative interviews with Syrian women and Lebanese health care providers confirm these findings. Furthermore, more men than women health care professionals were providing care during the pregnancy in UNHCR-contracted hospitals. One of the studies mentioned earlier found that male health care providers increased the probability of a CS [24]; however, we did not attempt to measure this in our study.

The high CS rates among Syrian refugee women are likely a combination of the numerous factors stated above. Our qualitative interviews found that Syrian refugee women report low ANC attendance, particularly when compared to a previous study undertaken in Syria [25], even though ANC services are free for Syrian refugee women. Unfortunately, currently UNHCR and its partners do not have sufficient quantitative data to confirm the low ANC coverage. However, low ANC attendance could be one significant factor that accounts for more high-risk pregnancies arriving at hospitals at time of delivery. Reasons for low ANC attendance for Syrian refugee women may include limited access due to insufficient or lack of services, shortage of money for transport and more expensive investigations or procedures, difficulty of access to care, or other more pressing needs given the difficult situation of being a refugee, and lack of female health care providers. Supporting providers’ statements that Syrian refugee women present late often with serious complications that require emergent CS, an analysis of the referral care requests sent to the UNHCR office found that 48 out of 150 total referral cases from May 27 to August 8, 2013, were for NICU admissions following birth. As stated above, hospital administrators reported having to close their maternity wards because their NICU was full.

Furthermore, the privatized Lebanese health care system that already has high CS rates for Lebanese likely plays an important factor. Besides the UNHCR partial or full payment for CS to UNHCR-contracted hospitals that may serve as an incentive for hospitals and doctors to perform CS, other important issues such as a purported preponderance of male doctors in the obstetric wards and increased complications at time of arrival to hospital with minimal to no previous obstetrical care likely play an important role for high CS rates among Syrian refugee women, despite their stated preference for NVD by a female provider at hospital.

The purported low ANC attendance and high CS rates of Syrian refugee women need to be actively addressed by the Lebanese government, UNHCR, and other organizations working with Syrian refugees.

Comprehensive, consistent, and systematic data collection remains a challenge in humanitarian emergencies. Efforts should nonetheless be undertaken to unify the data collected by government, private, and humanitarian organizations that refer refugees from primary care centers to all referral hospitals. A centralized patient database should be established so that data can reliably be used for monitoring, analysis, identification, reporting, and better decision-making. A set of agreed-upon indicators should be defined and used consistently to better track all refugee patients accessing care in Lebanon. The ANC coverage of Syrian refugee women by region in Lebanon needs to be assessed and barriers documented.

Audits and feedback to providers and hospital management on CS rates have an impact on reducing the rates of CS and increasing provider accountability. Identifying the barriers to change as well as the strategies that would be most efficient within the context of refugee health will help with an effective intervention as well as improvement of adherence to established and internationally accepted clinical guidelines.

The sex of the health care provider was an important factor for Syrian refugee women. Most obstetrical physicians in the hospitals were male, while midwives were always female. The former was often cited by midwives as an issue for many Syrian women and their husbands who often requested a female provider. A male-dominated field may also be a barrier for Syrian refugee women to access ANC. Midwives reported numerous discussions with Syrian refugee women to try to convince them to accept care from a male provider in hospital. UNHCR and its partners need to work with selected public and private health care providers at the primary care and hospital level to find solutions to this issue. The hiring of female health care providers by UNHCR and its partners to help the overstretched Lebanese health care services may be a possibility, including the use of qualified Syrian refugees.

Incentives for ANC attendance could be considered, such as baby welcome kits, transportation vouchers, or increased subsidization of medical costs related to pregnancy complications. The quality of ANC and the sex of health care providers also need to be assessed and possible improvements undertaken.

Sensitization of the Syrian refugee community about the importance of ANC, deliveries, and when CS may or may not be needed should be undertaken. The government, UNHCR and its partners have developed a wide range of methods to reach out at the individual, household, and community levels to Syrian refugees. These were used in the recent polio campaign and include text messages from UNHCR’s comprehensive database, traditional and social media, as well as home visits and via community centers.

There are limitations to this study that must be noted. While UNHCR’s referral partners recorded all hospital admissions and types of delivery, important maternal indicators (e.g., para, gravida, primary/secondary CS, gestational stage, birth complications) were often absent from the data. This limited our analysis and understanding of the causes behind the CS rates. A lack of data uniformity among referral partners made any comparison between hospitals or geographical areas difficult. Moreover, while most Syrian refugees access UNHCR-contracted hospitals for births, not all of them do, and thus not all deliveries by Syrian refugees were captured during this time period. For example, in the Bekaa region, many Syrian women chose to deliver in the Palestinian hospital where care is cheaper, often reimbursed by UNWRA, and midwives generally deliver the babies. Due to limited time and some logistical and security constraints, no hospitals in the North and South of Lebanon were visited for the qualitative component of the study.

In future studies of a similar nature, we would recommend that comparisons of CS rates between Syrian refugees and Lebanese are assessed. Furthermore, if the number of CS allows, we would recommend examining trends of CS by geographical region, context (e.g., urban, rural, informal tented settlements) and over time. While the overall CS rate is elevated, the data available do not always distinguish between primary and secondary CS, an indicator that should be considered in the future. Finally, a concomitant study of ANC coverage and barriers to access according to geographical region and context should occur.

The Syrian refugee crisis is a humanitarian tragedy whose magnitude has not been seen in recent history. Refugees fleeing the conflict in Syria have often settled in Lebanon in precarious living conditions. Those with the lowest socio-economic status live in informal tented settlements in rural areas with difficult access to established medical care services. Others are lost in the urban anonymity of cities. Some are unaware of the services available to them. A 2006 article on the Lebanese conflict and maternal care showed that the use of ANC sharply declined in displaced populations during that time. Issues related to accessibility and availability of services were the main determinants [11]. Seeking regular maternal care under these conditions is very challenging and may explain why many Syrian refugee women present very late to the hospital with minimal to no ANC together with health complications requiring emergent medical intervention such as CS. However, other factors such as a privatized Lebanese health care system, a guaranteed partial or full payment by UNHCR for CS, predominance of male obstetrical providers in hospitals may also be important factors. To address these issues, UNHCR must work with the government and other international, national, public, and private partners to assess and likely improve access to and quality of ANC for Syrian refugee women and sensitize refugees and health care workers to the risks and benefits of undertaking CS.

Abbreviations

- ANC

antenatal care

- CLMS

Caritas Labor Migrant Center

- CS

cesarean section

- IMC

International Medical Corps

- MF

Makhzoumi Foundation

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- NVD

normal vaginal delivery

- UNHCR

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- UNFPA

United Nations Population Fund

- WHO

World Health Organization

Appendix.

References

- WHO. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985;2:436–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) Caesarean section without medical indication increases risk of short-term adverse outcomes for mothers (Policy Brief) World Health Organization [Internet] 2010. [cited 14 May 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/rhr_hrp_10.20/en/ .

- Béhague DP, Victora CG, Barros FC. Consumer demand for caesarean sections in Brazil: informed decision making, patient choice, or social inequality? A population based birth cohort study linking ethnographic and epidemiological methods. BMJ. 2002;324:942–945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza J, Gülmezoglu A, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Carroli G, Fawole B. et al. Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004-2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Medicine. 2010;14:71. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J, Carroli G, Zavaleta N, Donner A, Wojdyla D, Faundes A. et al. Maternal and neonatal individual risks and benefits associated with caesarean delivery: multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2007;335:1025. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39363.706956.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja M, Jurdi R. Cesarean section rates in the Arab regions: A cross-national study. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:101–110. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja M, Choueiry N, Jurdi R. Hospital-based caesarean section in the Arab region: an overview. La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée orientale. 2009;15:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Lauer JA, Bing-Shun W, Thomas J, Van Look P. et al. Rates of caesarean section: Analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2007;21:98–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons L, Belizán JM, Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The Global Number and Costs of Additionally Needed and Unnecessary Caesarean sections performed per year: overuse as a barrier to universal coverage (Background Paper, No 30) WHO [Internet] 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/30C-sectioncosts.pdf .

- Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Reproductive Health in Crisis Situations. Reproductive Health Response In Crisis Consortium [Internet] Available from: http://misp.rhrc.org/ .

- Kabakian-Khasholian T, Shayboub R, El-Kak F. Seeking Maternal Care at Times of Conflict: The Case of Lebanon. Health Care for Women International. 2013;34(5):352–362. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.736570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstić D, Marinković D, Mirković L, Krstić J. Pregnancy outcome during the bombing of Yugoslavia from March 24 to June 9, 1999. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2006;63(4):377–382. doi: 10.2298/vsp0604377k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudić I, Radoncić F, Balić A, Fatusić Z. Operative deliveries in Clinic of Gynecology and Obstetrics Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina, during 1986-2005. Lijec Vjesn. 2009;131(9-10):248–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simetka O, Reilley B, Joseph M, Collie M, Leidinger J. Obstetrics during Civil War: six months on a maternity ward in Mallavi, northern Sri Lanka. Med Confl Surviv. 2002;18(3):258–270. doi: 10.1080/13623690208409634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Data. The World Bank [Internet] [cited 23 July 2013]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/country/lebanon#cp_wdi .

- Syrian Regional Refugee Response. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) [Internet] [cited 14 May 2014]. Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=122 .

- Kassak K, Mohammad A, Abdallah A. Opting for a Cesarean: What Determines the Decision? Public Administration & Management. 13(3):100–122. [Google Scholar]

- Syrian Arab Republic — Reproductive Health Profile. WHO [Internet] 2008. Available from: http://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa1162.pdf .

- Regional Situation Report for Syria Crisis. UNFPA. UNFPA [Internet] 2013. [cited 14 May 2014]. Available from: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=3189 .

- Kabakian-Khasholian T, Kaddour A, Dejong J, Shayboub R, Nassar A. The policy environment encouraging C-section in Lebanon. Health Policy. 2007;83(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health System Profile — Lebanon. WHO [Internet] 2006. [cited 14 May 2014]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js17301e/ .

- Network. Routines in facility-based maternity care: evidence from the Arab World. BJOG. 2005;112(9):1270–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayol M, Zein A, Ghosn N, Du Mazaubrun C, Breart G. Determinants of caesarean section in Lebanon: geographical differences. Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiology. 2008;22(2):136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamim H, El-Chemaly S, Nassar A, Aaraj A, Campbell O, Kaddour A. et al. Cesarean Delivery Among Nulliparous Women in Beirut: Assessing Predictors in Nine Hospitals. Birth. 2007;34(1):4–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashour H, Abdusalam A. Syrian women’s preferences for birth attendant and birth place. Birth. 2005;32(1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- At a glance: Syrian Arab Republic. UNICEF [Internet] [cited 14 May 2014]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/syria_statistics.html .

- Births attended by skilled health staff. The World Bank [Internet] [cited 19 Mar 2014]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.BRTC.ZS .