This article discusses use of laser technologies in acute management of soft tissue injuries in surgical incisions and trauma. To minimize scar formation, current standard of care in acute management of surgical incisions includes irrigation and cleansing, multilayered, tension-free closure with precise approximation and eversion of wound edges, judicious use of suture material, use of postoperative moisture barrier or dressing, and early removal of surgical sutures. Traumatic soft tissue injury involving the skin can be more challenging to manage acutely due to frequent presence of crushed, macerated, or otherwise devitalized tissues. Additional steps are often warranted in that setting including removal of foreign bodies, copious irrigation of the wound, removal of clearly devitalized tissues, and use of antibiotics to cover polymicrobial flora. Despite these measures, poor cosmetic outcome is frequent after surgical procedures and traumatic skin injuries.

Numerous adjunctive measures have been proposed to optimize wound healing and obviate the need for operative scar revision, many of which are discussed in this volume. These include use of steroids, post-treatment dressings, avoidance of sunlight, dermabrasion, and laser treatment. In classic dermabrasion, mechanical debridement of the superficial papillary dermis leads to re-epithelialization via the adnexal structures, resulting in improved texture and color of the skin. This is an excellent method for smoothing an irregular surface or correcting pigmentary discrepancy between adjacent skin edges, which alters how light creates shadows across the surface. Dermabrasion is recommended 6 to 8 weeks after injury/surgical procedure. More substantial improvements are reported during this period, as the immature scar is still undergoing remodeling, rather than during the mature phase.1 Proposed mechanism of action for this modality has been described by Harmon and colleagues2 as reorganization of connective tissue ultrastructure and epithelial cell–cell interactions with an increase in collagen bundle density and size with a tendency toward unidirectional orientation of fibers parallel to the epidermal surface. Although excellent outcomes have been described with this technique, it does require a fair level of operator experience and learning curve for manual control of the depth of dermabrasion and feathering of the edges. Additionally, this technique can be complicated with excessive bleeding and tearing of tissues at the treatment margin. Laser scar revision is a competing technology that has gained increasing popularity due to the potential for excellent hemostasis, ease of use, and precise control over depth of penetration and extent of treatment.

Since the introduction of laser skin resurfacing for aesthetic surgery in the mid-1990s, the technology has worked its way into broad use in scar revision. Laser and optical methods for management of acute injury have very vital roles in postsurgical and traumatic wound therapeutic outcome. With advances in this technology a clinician may arrive at a crossroads in the decision to treat a scar with surgical revision versus dermabrasion or various laser technologies. The authors present and review their experience herein to help with this decision-making process in the acute setting. This article discusses indications and strengths of available optical modalities with a focus on acute and subacute skin injuries. The discussion is practically oriented and structured around the specific applications of each technology.

ACUTE COSMETIC MANAGEMENT OF SURGICAL WOUNDS

Scars can be disfiguring, aesthetically unacceptable, and cause pruritis, tenderness, pain, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression in postsurgical patients. Regardless of the specific strategy for treatment, current optical technologies offer the reconstructive surgeon valuable tools to lessen the psychological burden of undergoing surgery by optimizing the cosmetic outcome in a noninvasive or minimally invasive form. Availability of these tools can lead to higher levels of patient satisfaction after surgery.

For purposes of this discussion, a surgical incision is defined as an incision that is closed per standard of care as discussed previously with optimal postsurgical care and without perioperative wound complications. Ideal post-surgical scar is flat, flexible and indiscernible from surrounding skin in terms of color and texture. Despite optimal wound closure and postoperative care, aberrant fibroblast response can lead to hypertrophic or keloid scars, and aberrant angiogenesis may lead to telangiectasias or a hyperemic scar. Imperfect surgical closure or poor postoperative management can lead to poor outcomes with step-offs, depressions, suture marks, dyspigmentation, or broad hypertrophic scars due to wound tension or distal flap vascular compromise and tissue necrosis. Abnormal collagen deposition has been demonstrated histologically in hypertrophic scars with elevated levels of collagen 33 Traditionally improved via mechanical dermabrasion, the current arsenal for optimization of surgical wounds includes various optical technologies such as conventional ablative laser resurfacing and nonablative laser treatment, as well as fractionated and pulsed laser technologies. Acute optimization of wound healing can start immediately after the completion of surgery as in laser-assisted scar healing (LASH)4 or after removal of sutures within 1week postoperatively, or it may focus on treatment of maturing scar several weeks to months after surgery.

ACUTE COSMETIC MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMATIC WOUNDS

Some injuries such as uncomplicated linear lacerations are indistinguishable from surgical incisions. The challenge with traumatic skin injuries lies in irregular borders, high tension, macerated tissue, and tissue loss. More often than not, traumatic lacerations involve nonlinear or stellate disruption of the epidermis that is not at right angle to the skin surface. Traumatic abrasions can harbor foreign bodies, which if not adequately debrided, can lead to traumatic tattooing. Presence of tissue edema, hematoma, and loss of tissue can force a high-tension closure, which can lead to broad hypertrophic scarring. Risk of infection is compounded by inadequate cleansing and irrigation of tissues and lack of proper antibiotic coverage after repair. Devitalized, necrosed skin edges and infected wounds can lead to severe atrophic or hypertrophic scars and extremely poor cosmetic outcomes. Use of copious irrigation and antibiotic coverage for gram-positive skin flora with first- or second-generation cephalosporins or clindamycin should be considered in these patients. In the case of an animal or human bite or other gross contaminations of the wound, appropriate adjustments to the antibiotic coverage must be made.

Due to the specific patient population as well as the treatment setting, poor follow-up is often an issue with these patients, leading to improper postoperative care such as suture retention or delay in diagnosis of wound infection. Use of rapidly absorbing suture material where available and appropriate is therefore advised in traumatic skin closure, particularly in those whose attention to follow-up is uncertain. Delayed presentation to the surgeon can also be an issue in this population, as the patient is often acutely managed by an emergency room physician, family doctor, physician assistant, or a general surgeon as opposed to a specialist with reconstructive surgical expertise. Intervention should occur as early as possible following presentation to prevent progression in the direction of an undesirable mature scar that may require surgical revision.

OPTICAL MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE SURGICAL AND TRAUMATIC WOUNDS

This discussion encompasses conventional ablative resurfacing lasers, pulsed dye laser (PDL), and fractionated lasers for acute cosmetic optimization of surgical and traumatic wounds.

Ablative Laser Resurfacing

Traditional laser resurfacing is a technique that is commonly accomplished via ablative devices such as conventional carbon dioxide (CO2) or Erbium:YAG lasers. Mechanism of action is similar to using a mechanical dermabrader with the potential to modulate wound healing through thermal effects of laser and trigger the same regenerative mechanisms as when these devices are used for classic facial resurfacing. Tissue removal by laser is a function of treatment parameters, tissue optical properties, and tissue thermal properties. Histologically, laser-treated skin shows a subepidermal dermal repair zone consisting of compact new collagen fibers overlying collagen with evidence of solar elastosis.5 Because it is possible to achieve discrete, measurable incremental amounts of tissue removal with each pulse, only a modest level of skill is required for achieving optimal results.

CO2

The CO2 laser is the work horse of cosmetic dermatology and the model to which all optical therapies are compared. Despite nearly 20 years of use, CO2 laser skin resurfacing remains very valuable due to the capacity to remove bulk amounts of tissue in a bloodless fashion, and correct iatrogenic contour irregularities. Differences of outcomes between CO2 and dermabrasion remain incompletely understood.6,7 However, due to decreasing technology associated costs, CO2 laser resurfacing has slowly gained popularity. CO2 laser is emitted at wavelengths ranging from 9400 to 10,600 nm, and it is preferentially absorbed by water (its principal chromophore), leading to superficial ablation of tissue by vaporization. Although the majority of the energy is absorbed by the first 20 to 30 μm of the skin, the zone of thermal damage can be as much as 1 mm deep.8 This is in part responsible for the persistent erythema experienced by patients that can continue for 6 months or longer after CO2 laser treatment, but it may also contribute to enhanced collagen remodeling. Timing of the treatment is typically the same as mechanical dermabrasion, optimally performed 4 to 8 weeks after the initial injury. The ideal application of this laser is for induction of contour changes and collagen remodeling in elevated scars.

Erbium:YAG Laser

Introduced to dermatology in the mid-1990s, the Erbium:YAG laser also removes tissue, but the penetration depth of the wavelength (2936 nm) is shallow, as is the corresponding depth of thermal injury. Light from this laser is absorbed 12 to 18 times more efficiently by water compared with the CO2 laser. However, the more superficial depth of penetration and surrounding tissue injury lead to decreased induction of collagen remodeling and contraction.9 Due to poor coagulative properties, hemostasis can also be a problem with this modality, particularly if extensive tissue needs to be removed. Application of this laser is for generating subtle contour changes in depressed and atrophic scars. Additionally, the Erbium:YAG laser may be used in cases where thermal injury is undesirable (such as a known keloid former).

PDL

PDL relies upon concept of selective photothermolysis.10 The 585 to 595 nm wavelengths are preferentially absorbed by hemoglobin, although epidermal melanin absorption can be of concern in patients with darker skin phototypes. This selectivity makes this technology ideal for in the treatment of vascular lesions skin lesions such as telangiectasia, port wine stains, and hemangiomas. During scar treatment, PDL destroys the blood supply to the wound edge at the level of dermal microvasculature, inhibiting the formation of scars. The angiolytic mechanism of action has been disputed by some authors.11 Alternatively, changes in cell cycle distribution of fibroblasts in keloid scars has been proposed recently as a mechanism of action of PDL treatment in keloid scars.12

Properties of this laser make it suitable for treatment of red, hyperemic, hypertrophic scars, and keloids (Figs. 1–3). PDL improves color, texture, and pliability of scars by reducing pigmentation, vascularity, and bulk of scar tissue.13 Because it spares the epidermal and dermal tissues, treatment can be repeated at 6- to 8-week intervals with significantly reduced downtime and erythema compared with conventional CO2 laser resurfacing. Due to competitive absorption of the emitted energy by melanin, darker toned individuals (Fitzpatrick IV–V) may not be suitable candidates for this treatment due to risk of dyspigmentation.14 The authors’ parameters for PDL wound optimization are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Hypervascular scar treated using the pulsed dye laser. Top: before treatment. Bottom: after treatment.

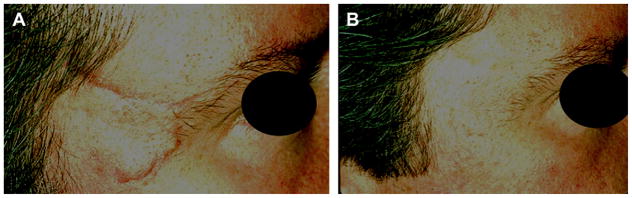

Fig. 3.

Hypervascular scar treated using the pulsed dye laser. (A) Before treatment. (B) After 3 treatments.

Table 1.

Author parameters for laser devices

| Device | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Pulsed dye laser | Low fluence (4 to 5 J/cm2), short pulse (0.45 ms), large spot 10 to 12 mm, 30/30 DCD, starting 2 to 4 weeks after suture removal, 4- to 6-week treatment intervals |

| Sciton Profractional | 250–600 μm spot size, 20% to 30% coverage, starting 2 to 4 weeks after suture removal, 4- to 6-week treatment intervals |

| Fraxel Re:Store | 20 mJ and 32% density, starting 2 weeks after suture removal, 4 to 6 treatments at 2-week intervals |

Abbreviation: DCD, dynamic cooling device.

Fractional Photothermolysis

Fractional photothermolysis, first introduced by Manstein and colleagues15 in 2004, is the latest in the available phototherapeutics for scars. Fractionation refers to a technology in which thousands of pinpoint laser beams are directed at the skin surface simultaneously in such a way as to target a fraction of the overall surface area while sparing the intervening areas of skin. Confluent epidermal damage is thus avoided. Mechanism of action is via initial induction of proinflammatory cytokines followed by dermal remodeling and collagen induction.16 Re-epithelialization is observed after as early as 1 day, leading to reduced downtime and higher patient satisfaction.

First fractional lasers were nonablative using midinfrared Erbium-doped fiber lasers. However, the technology base has broadened to include a number of ablative and nonablative fractionated lasers such as 532 nm diode, 850 to 1350 nm infrared, 1064 to 2940 nm Er:YAG, 2790 nm yttrium scandium gallium garnet (YSGG), and 10,600 nm CO2. The exact technique and device parameters, including microablation spot size and density, are highly variable and are physician-and device-dependent. No ideal fractionation pattern has been established to date. These lasers have demonstrated efficacy in improvement of surgical and traumatic atrophic and hypertrophic scars (see Figs. 2 and 4).17,18 The chief advantage of these lasers is their superior adverse effect profile compared with conventional ablative lasers, including lower risk of scarring and dyspigmentation, along with proven effectiveness.

Fig. 2.

Patient with scar after angiofibroma excision treated by pulsed dye and Er:YAG laser fractional rejuvenation. (A) Before treatment. (B) After 1 treatment.

Fig. 4.

Dog bite scar treated by Er:YAG Profractional laser. (A) Before treatment. (B) After 2 treatments.

Timing of Treatment

Most reconstructive surgical interventions are focused on timing with respect to return of tissue mechanical stability. Conventional laser resurfacing and mechanical dermabrasion can potentially destabilize a healing tissue bed or disrupt protective epidermal barrier before the incision seals. Therefore the optimal time for treatment is during the premature phase of scar formation at approximately 6 to 8 weeks after injury. Newer nonablative, pulsed, or fractionated lasers place minimal mechanical stress on the tissues, making an argument for earlier treatments. Earlier intervention can in theory alter the inflammatory phase of wound healing and change fibroblast migration, leading to a reduction in the appearance of scars. Additionally, alterations in microcirculation of the wound induced by laser treatment may be responsible for prevention of excessive scar formation at the incision line.

Benefits of early treatment with PDL for prevention of traumatic and surgical scars were initially demonstrated in a study by McGraw and colleagues19 in 1999. Treatment within the first few weeks resulted in faster resolution of scar stiffness and erythema, and less frequent development of hypertrophic scarring. Moreover, excellent color blending of the treated scars was obtained after treatment. Other studies have since confirmed the benefits of treatment as early as the time of suture removal.20,21 Initial consensus recommendations for nonablative fractional laser Fraxel (Reliant Technologies Incorporated, Mountain View, CA, USA) included treatment at 2 to 4 weeks after injury/postoperatively.22 Results of early treatment with fractional laser are depicted in Figs. 5 and 6, with parameters listed in Table 1.

Fig. 5.

Traumatic scar shown (A) before and (B) 2 weeks after 5 treatments with Fraxel Re:Store.

Fig. 6.

Another traumatic scar. Lower half of the scar is shown after 5 treatments with Fraxel

Further development of the concept of early interference has led to the development of LASH. This was first proposed by Capon and colleagues4 in 2001 using an 815 nm diode laser. In animal subjects, they demonstrated accelerated healing with an earlier continuous dermis and epidermis, resulting in a less discernible scar. Tensile strength was significantly greater than control at 7 and 15 days. Clinical trials have affirmed this result, and benefits of the use of this technique in a known hypertrophic scar former have also been demonstrated since the pilot study.23–25 These preliminary results seem encouraging, but further clinical studies to confirm the effects and to elucidate the exact mechanisms of action are warranted.

Treatment of Traumatic Tattoos

Inadequate primary cleansing of dirt-ingrained skin abrasions can result in disfiguring traumatic tattoos. The resultant discoloration has been successfully treated with excision, dermabrasion, salabrasion, overgrafting, cryotherapy, and micro-surgical removal, in addition to optical treatments. Laser treatment of collagen-entrapped pigmented particles takes advantage of selective photothermolysis principle. As such, it is theorized that selective absorption of thermal energy by the entrapped particles leads to shattering of the particles into numerous smaller particles that are subsequently phagocytosed and removed by macrophages. Q-switching is a laser technology with widespread use in removal of elective tattoos that allows production of high peak powered pulses with extremely short nanosecond pulse durations. Q-switched ruby, alexandrite, and Nd-YAG lasers have all been demonstrated as effective treatment modalities for traumatic tattoos.26–29 Repeated treatments, spaced apart by a minimum of 1 month, may be necessary.

Adverse Effects and Complications of Laser Treatment

Despite relative safety and efficacy of laser scar revision, adverse effects and complications may arise that the treating clinician must be aware of and manage. As previously described, conventional CO2 laser resurfacing can lead to a significant thermal damage to tissues. Continuous wave lasers, in particular the CO2 lasers, carry the risk of scarring due to considerable collateral thermal damage and necrosis. Hypertrophic scarring is a rare complication of treatment often caused by poor intraoperative technique, and it is treated with topical or intralesional steroids or PDL. Intense postoperative erythema lasting up to 6 months after treatment is an indicator of the degree of nonspecific tissue injury. Intensity and duration are most pronounced with conventional CO2 lasers. In addition to the erythema, complete epidermal ablation produces an exposed weeping wound along with edema, pain, and pruritis during the initial week after treatment. These symptoms can be managed with cold compresses, pain control, steroids, and antihistamines. Irritation of the skin at this stage can also lead to acne eruptions and contact dermatitis. Infectious complications include reactivation of herpes simplex virus and bacterial and fungal infections. Close monitoring and appropriate antibiotic/antiviral treatment and preoperative prophylaxis for herpetic infection can minimize the incidence and adverse sequelae of these infections. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can complicate recovery of patients with darker skin types and is generally managed with topical bleaching agents, steroids, and retinA. Incidence of complications can be substantially reduced with careful patient selection, preoperative planning, and meticulous treatment technique. Early detection and treatment of complications is the key to circumventing poor treatment outcomes.

SUMMARY

An unsightly scar negatively affects patients as an unwelcome and often public reminder of a traumatic incident or surgical procedure. Conventional CO2 is a powerful tool for nonsurgical revision of traumatic and surgical scars, promising excellent results. Unfortunately, the extended recovery period and the adverse effect profile of the treatments make some patients hesitate to undergo this treatment. Newer targeted therapies such as PDL, fractional laser, and nonablative lasers have moderate adverse effect profiles and rapid recovery periods while striving to achieve cosmetic results that approach conventional CO2 laser resurfacing via earlier interventions.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Katz BE, Oca AG. A controlled study of the effectiveness of spot dermabrasion (scarabrasion) on the appearance of surgical scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(3):462–6. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70074-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harmon CB, Zelickson BD, Roenigk RK, et al. Dermabrasive scar revision. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evaluation. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21(6):503–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveira GV, Hawkins HK, Chinkes D, et al. Hypertrophic versus nonhypertrophic scars compared by immunohistochemistry and laser confocal microscopy: type I and III collagens. Int Wound J. 2009;6(6):445–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2009.00638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capon A, Souil E, Gauthier B, et al. Laser-assisted skin closure (LASC) by using a 815-nm diode-laser system accelerates and improves wound healing. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28(2):168–75. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotton J, Hood AF, Gonin R, et al. Histologic evaluation of preauricular and postauricular human skin after high-energy, short-pulse carbon dioxide laser. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(4):425–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitzmiller WJ, Visscher M, Page DA, et al. A controlled evaluation of dermabrasion versus CO2 laser resurfacing for the treatment of perioral wrinkles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(6):1366–72. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200011000-00024. [discussion: 1373–4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nehal KS, Levine VJ, Ross B, et al. Comparison of high-energy pulsed carbon dioxide laser resurfacing and dermabrasion in the revision of surgical scars. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(6):647–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green HA, Domankevitz Y, Nishioka NS. Pulsedcarbon dioxide laser ablation of burned skin: in vitro and in vivo analysis. Lasers Surg Med. 1990;10(5):476–84. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900100513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman JB, Lord JL, Ash K, et al. Variable pulse erbium:YAG laser skin resurfacing of perioral rhytides and side-by-side comparison with carbon dioxide laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2000;26(2):208–14. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(2000)26:2<208::aid-lsm12>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220(4596):524–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6836297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison KP, Kiernan MN, Waters RA, et al. Pulsed dye laser treatment of burn scars. Alleviation or irritation? Burns. 2003;29(3):207–13. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhibo X, Miaobo Z. Molecular mechanism of pulsed-dye laser in treatment of keloids: an in vitro study. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010;23(1):29–33. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000363486.94352.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alster TS. Improvement of erythematous and hypertrophic scars by the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32(2):186–90. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199402000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong AK, Tan OT, Boll J, et al. Ultrastructure: effects of melanin pigment on target specificity using a pulsed dye laser (577 nm) J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88(6):747–52. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manstein D, Herron GS, Sink RK, et al. Fractional photothermolysis: a new concept for cutaneous remodeling using microscopic patterns of thermal injury. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;34(5):426–38. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orringer JS, Rittie L, Baker D, et al. Molecular mechanisms of nonablative fractionated laser resurfacing. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(4):757–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunzeker CM, Weiss ET, Geronemus RG. Fractionated CO2 laser resurfacing: our experience with more than 2000 treatments. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(4):317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haedersdal M. Fractional ablative CO(2) laser resurfacing improves a thermal burn scar. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(11):1340–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCraw JB, McCraw JA, McMellin A, et al. Prevention of unfavorable scars using early pulse dye laser treatments: a preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42(1):7–14. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conologue TD, Norwood C. Treatment of surgical scars with the cryogen-cooled 595 nm pulsed dye laser starting on the day of suture removal. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(1):13–20. doi: 10.1111/1524-4725.2006.32002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nouri K, Jimenez GP, Harrison-Balestra C, et al. 585-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of surgical scars starting on the suture removal day. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(1):65–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29014.x. [discussion: 73] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherling M, Friedman PM, Adrian R, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of an erbium-doped 1550-nm fractionated laser and its applications in dermatologic laser surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(4):461–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capon A, Iarmarcovai G, Gonnelli D, et al. Scar prevention using laser-assisted skin healing (LASH) in plastic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(4):438–46. doi: 10.1007/s00266-009-9469-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capon A, Iarmarcovai G, Mordon S. Laser-assisted skin healing (LASH) in hypertrophic scar revision. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11(4):220–3. doi: 10.3109/14764170903352878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choe JH, Park YL, Kim BJ, et al. Prevention of thyroidectomy scar using a new 1550 nm fractional erbium–glass laser. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(8):1199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achauer BM, Nelson JS, Vander Kam VM, et al. Treatment of traumatic tattoos by Q-switched ruby laser. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93(2):318–23. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang SE, Choi JH, Moon KC, et al. Successful removal of traumatic tattoos in Asian skin with a Q-switched alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(12):1308–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dufresne RG, Jr, Garrett AB, Bailin PL, et al. CO2 laser treatment of traumatic tattoos. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(1):137–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haywood RM, Monk BE, Mahaffey PJ. Treatment of traumatic tattoos with the Nd YAG laser: a series of nine cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52(2):97–8. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1998.3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]