Abstract

Background

In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) outcomes vary widely between hospitals, even after adjusting for patient characteristics, suggesting variations in practice as a potential etiology. However, little is known about the standards of IHCA resuscitation practice among US hospitals.

Objective

To describe current US hospital practices with regard to resuscitation care.

Design

A nationally representative mail survey.

Setting

A random sample of 1,000 hospitals from the American Hospital Association database, stratified into nine categories by hospital volume tertile and teaching status (major teaching, minor teaching and non-teaching).

Subjects

Surveys were addressed to each hospital's CPR Committee Chair or Chief Medical/Quality Officer.

Measurements

A 27-item questionnaire.

Results

Responses were received from 439 hospitals with a similar distribution of admission volume and teaching status as the sample population (p=0.50). Of the 270 (66%) hospitals with a CPR committee, 23 (10%) were chaired by a Hospitalist. High frequency practices included having a Rapid Response Team (91%) and standardizing defibrillators (88%). Low frequency practices included therapeutic hypothermia and use of CPR assist technology. Other practices such as debriefing (34%) and simulation training (62%) were more variable and correlated with the presence of a CPR Committee and/or dedicated personnel for resuscitation quality improvement. The majority of hospitals (79%) reported at least one barrier to quality improvement, of which the lack of a resuscitation champion and inadequate training were the most common.

Conclusions

There is wide variability between hospitals and within practices for resuscitation care in the US with opportunities for improvement.

Keywords: cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, code blue

Introduction

An estimated 200,000 adult patients suffer cardiac arrest in U.S. hospitals each year, of which less than 20% survive to hospital discharge.1,2 Patient survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA), however, varies widely across hospitals, and may be partly attributed to differences in hospital practices.3-5 While there are data to support specific patient-level practices in the hospital, such as delivery of electrical shock for ventricular fibrillation within two minutes of onset of the lethal rhythm,6 little is known about in-hospital systems-level factors. Similar to patient-level practices, some organizational and systems level practices are supported by international consensus and guideline recommendations.7,8 However, the adoption of these practices is poorly understood. As such, we sought to gain a better understanding of current US hospital practices with regard to IHCA and resuscitation with the hopes of identifying potential targets for improvement in quality and outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a nationally representative mail survey between May and November 2011, targeting a stratified random sample of 1000 hospitals. We utilized the U.S. Acute-Care Hospitals (FY2008) database from the American Hospital Association to determine the total population of 3809 Community Hospitals (i.e., nonfederal government, nonpsychiatric, and non long-term care hospitals).9 This included General Medical and Surgical, Surgical, Cancer, Heart, Orthopedic and Children's Hospitals. These hospitals were stratified into tertiles by annual in-patient days and teaching status (major, minor, non-teaching), from which our sample was randomly selected (Figure 1). We identified each hospital's CPR Committee (sometimes known as “code committee”, “code blue committee” or “cardiac arrest committee”) Chair or Chief Medical/Quality Officer, to whom the paper-based survey was addressed, with instructions to forward to the most appropriate person if someone other than the recipient. This study was evaluated by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt from further review.

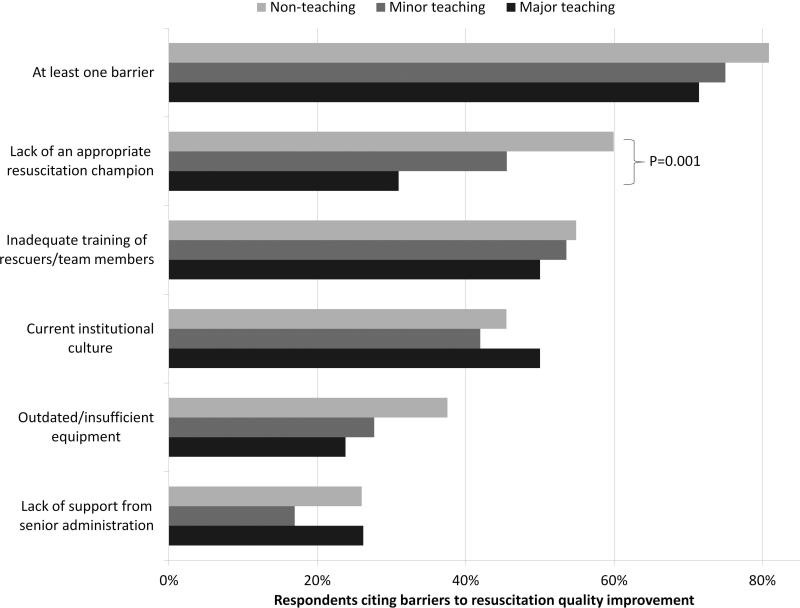

Figure 1. Hospital responders to in-hospital resuscitations by institution type and level of participation.

Bars represent the percent of hospitals reporting usual resuscitation responders in their hospitals, stratified by the teaching status of the hospital. Each bar is further subdivided by the likelihood of that provider to lead the resuscitation.

Survey

The survey content was developed by the study investigators and iteratively adapted by consensus and beta testing to require approximately 10 minutes to complete. Questions were edited and formatted by the University of Chicago Survey Lab (Chicago, IL) to be more precise and generalizable. Surveys were mailed in May 2011 and re-sent twice to non-responders. A $10 incentive was included in the second mailing. When more than one response from a hospital was received, the more complete survey was used or, if equally complete, the responses were combined. All printing, mailing, receipt control, and data entry were performed by the University of Chicago Survey Lab and data entry was double-keyed to ensure accuracy.

Response rate was calculated based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research standard response rate formula.10 It was assumed that the portion of non-responding cases were ineligible at the same rate of cases for which eligibility was determined. A survey was considered complete if at least 75% of individual questions contained a valid response, partially complete if at least 40% but less than 75% of questions contained a valid response, and a non-response if less than 40% was completed. Non-responses were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using a statistical software application (Stata version 11.0, Statacorp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were calculated and presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range). A chi-squared statistic was used to assess bias in response rate. We determined a priori two indicators of resource allocation (availability of a CPR committee and dedicated personnel for resuscitation quality improvement) and tested their association with quality improvement initiatives, using logistic regression to adjust for hospital teaching status and number of admissions as potential confounders. All tests of significance used a 2-sided p<0.05.

Results

Responses were received from 439 hospitals (425 complete and 14 partially complete), yielding a response rate of 44%. One subject ID was removed from the survey and could not be identified, so it was excluded from any analyses. Hospital demographics were similar between responders and non-responders (p=0.50) (Table 1). Respondents who filled out the surveys included Chief Medical/Quality Officers [n=143 (33%)], Chairs of CPR Committees [n=64 (15%)], members of CPR Committees [n=29 (7%)], Chiefs of Staff [n=33 (8%)], Resuscitation Officers/Nurses [n=27 (6%)], Chief Nursing Officers [n=13 (3%)], and others [n=131 (30%)].

Table 1.

Stratified response rates by hospital volume and teaching status.

| Annual inpatient days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching status | <17,695 | 17,695-52,500 | >52,500 | Total |

| Major | 1/2 (50) | 1/8 (13) | 40/82 (49) | 42/92 (46) |

| Minor | 13/39 (33) | 40/89 (45) | 62/133 (47) | 115/261 (44) |

| Nonteaching | 141/293 (48) | 100/236 (42) | 40/118 (34) | 281/647 (43) |

| Total | 156/335 (47) | 143/335 (43) | 145/336 (43) | 438/1000 (44) |

Results are shown as number of respondents/total sampled (%).

Table 2 summarizes structure, equipment, quality improvement and pre- and post-arrest practices across the hospitals. Of note, 77% of hospitals (n=334) reported having a pre-designated, dedicated code team and 66% (n=281) reported standardized defibrillator make and model throughout their hospital. However, less than one-third of hospitals utilized any CPR assist technology (e.g., CPR quality sensor or mechanical CPR device). The majority of hospitals reported having a Rapid Response Team (RRT) [n=391 (91%)]. Although a therapeutic hypothermia protocol for post-arrest care was in place in over half of hospitals [n=252 (58%)], utilization of hypothermia for patients with return of spontaneous circulation was infrequent.

Table 2.

In-hospital resuscitation structure and practices.

| STRUCTURE | n (%) | 2010 AHA Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Existing CPR Committee | 270 (66) | |

| CPR Chair | ||

| Physician only | 129 (48) | |

| Nurse only | 90 (34) | |

| Nurse/Physician co-chair | 31 (12) | |

| Other | 17 (6) | |

| Clinical specialty of chaira | ||

| Pulmonary/Critical Care | 79 (35) | |

| Emergency Medicine | 71 (31) | |

| Anesthesia/Critical Care | 43 (19) | |

| Cardiology | 38 (17) | |

| Other | 32 (14) | |

| Hospital Medicine | 23 (10) | |

| Pre-determined cardiac arrest team structure | 334 (77) | |

| Notifications of Respondersa | ||

| Hospital-wide PA | 406 (93) | |

| Pager/Calls to individuals | 230 (53) | |

| Local alarm | 49 (11) | |

| EQUIPMENT | ||

| AEDs used as primary defibrillator by location | ||

| High acuity inpatient areas | 69 (16) | |

| Low acuity inpatient areas | 109 (26) | |

| Outpatient areas | 206 (51) | Class IIb, LOE Cd |

| Public areas | 263 (78) | Class IIb, LOE Cd |

| Defibrillator throughout hospital | ||

| Same brand and model | 281 (66) | |

| Same brand, different models | 93 (22) | |

| Different brands | 54 (13) | |

| CPR assist technology useda | ||

| None | 291 (70) | |

| Capnography | 106 (25) | Class IIb, LOE Cd |

| Mechanical CPR | 25 (6) | Class IIb, LOE B/Cb, d |

| Feedback device | 17 (4) | Class IIa, LOE B |

| QUALITY IMPROVEMENT | ||

| IHCA tracked | 336 (82) | Supported c, d |

| Data reviewed | Supported c, d | |

| Data not tracked / Never reviewed | 85 (20) | |

| Intermittently | 53 (12) | |

| Routinely | 287 (68) | |

| Routine cardiac arrest case reviews/debriefing | 149 (34) | Class IIa, LOE C |

| Dedicated staff to resuscitation QI | 196 (49) | |

| Full-time equivalent staffing, median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.25-1.2) | |

| Routine simulated resuscitation training | 268 (62) | |

| PRE AND POST ARREST MEASURES | ||

| Hospitals with RRT | 391 (91) | Class I, LOE Cd |

| Formal RRT-specific training | ||

| Never | 50 (14) | |

| Once | 110 (30) | |

| Recurrent | 163 (45) | |

| TH protocol/order set in place | 252 (58) | |

| Percent of patients with ROSC receiving TH | Class IIb, LOE Bd | |

| Less than 5% | 309 (74) | |

| 5% - 25% | 68 (16) | |

| 26% - 50% | 11 (3) | |

| 51% - 75% | 10 (2) | |

| More than 75% | 18 (4) | |

Abbreviations: AHA, American Heart Association; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; AED, automatic external defibrillator; IHCA, in-hospital cardiac arrest; QI, quality improvement; IQR, inter-quartile range; RRT, rapid response team; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; TH, therapeutic hypothermia; LOE, level of evidence. Results shown as total (%), unless otherwise indicated. Percentages were adjusted by excluding missing responses.

These categories are not mutually exclusive.

May be considered for use in specific settings by properly trained personnel.

Supported in the Guidelines without official class recommendation.

Recommended or supported in 2005 Guidelines.

Hospitals reported that routine responders to IHCA events included respiratory therapists [n=414 (95%)], critical care nurses [n=406 (93%)], floor nurses [n=396 (90%)], attending physicians [n=392 (89%)], physician trainees [n=162 (37%)] and pharmacists [n=210 (48%)]. Figure 1 shows the distribution of responders and team leaders by hospital type. Of the non-teaching hospitals, attending-level physicians were likely to respond at 94% (265/281) and routinely lead the resuscitations at 84% (236/281), while of major teaching hospitals, attending physicians were only likely to respond at 71% (30/42) and routinely lead at 19% (8/42).

Two-thirds of the hospitals had a CPR committee [n=270 (66%)], and 196 (49%) had some staff time dedicated to resuscitation quality improvement. Hospitals with a specific committee dedicated to resuscitation and/or dedicated staff for resuscitation quality improvement were more likely to routinely track cardiac arrest data (OR 3.64 [95% CI: 2.05 - 6.47] and OR 2.02 [1.16 - 3.54] respectively) and review the data (OR 2.67 [1.45 - 4.92] and OR 2.18 [1.22 - 3.89] respectively), after adjusting for teaching status and hospital size. These hospitals were also more likely to engage in simulation training and debriefing (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation between resource availability and quality improvement practices.

| CPR committee (n = 406) | Dedicated QI staff (n = 398) | |

|---|---|---|

| IHCA tracking | 3.64 (2.05, 6.47) | 2.02 (1.16, 3.54) |

| Routinely review | 2.67 (1.45, 4.92) | 2.18 (1.22, 3.89) |

| Simulation training | 2.63 (1.66, 4.18) | 1.89 (1.24, 2.89) |

| Debriefing | 3.19 (1.89, 5.36) | 2.14 (1.39, 3.32) |

Abbreviations: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; QI, quality improvement; IHCA, in-hospital cardiac arrest. Logistic regression adjusting for hospital size and teaching status was performed. All results shown as OR (95% CI).

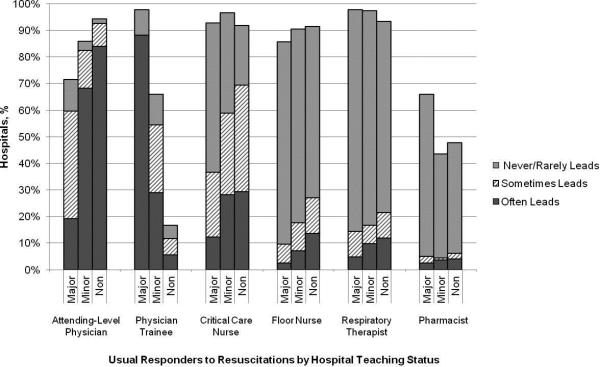

Ninety percent (n=391) of respondents agreed that “there is room for improvement in resuscitation practice at my hospital” and 70% (n=302) agreed that “improved resuscitation would translate into improved patient outcomes.” Overall, 78% (n=338) cited at least one barrier to improved resuscitation quality, of which the lack of adequate training [n=233 (54%)] and the lack of an appropriate champion [n=230 (53%)] were the most common. In subgroup analysis, non-teaching hospitals were significantly more likely to report the lack of a champion than their teaching counterparts (p=0.001) (Figure 2). In addition, we analyzed the data by hospitals that reported lack of a champion was not a barrier and compared them to those for whom it was, and found significantly higher adherence across all the measures in Table 2 supported by the 2010 guidelines, with the exception of real-time feedback (data not shown).

Figure 2. Barriers to resuscitation quality improvement by institution type.

Bars represent the percent of responders reporting specific perceived barriers to resuscitation quality improvement at their hospital, stratified by the teaching status of the hospital.

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of hospitals, we found considerable variability in cardiac arrest and resuscitation structures and processes, suggesting potential areas to target for improvement. Some practices, including use of RRTs and defibrillator standardization, were fairly routine, while others, such as therapeutic hypothermia and CPR assist technology, were rarely utilized. Quality initiatives, such as data tracking and review, simulation training and debriefing, were variable.

Several factors likely contribute to the variable implementation of evidence-based practices. Guidelines alone have been shown to have little impact on practice by physicians in general.11 This is supported by the lack of correlation we found between the presence, absence or strength of specific American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care treatment recommendations and the percent of hospitals reporting performing that measure. It is possible that other factors, such as a lack of familiarity or agreement with those guidelines or the presence of external barriers may be contributing.12,13 Specifically, the importance of a clinical champion was supported by our finding that hospitals reporting lack of a champion as a barrier were less likely to be adherent with guidelines. However, since the study did not directly test the impact of a champion, we wanted to be careful to avoid overstating or editorializing our results.

Some of the variability may also be related to the resource intensiveness of the practice. Routine simulation training and debriefing interventions, for example, are time intensive and require trained personnel to institute. That may explain the correlation we noted between these practices and the presence of CPR committee and dedicated personnel. The use of dedicated personnel was rare in this study, with less than half of respondents reporting any dedicated staff and a median of 0.5 full-time equivalents (FTEs) for those reporting positively. This is in stark contrast to the routine use of resuscitation officers (primarily nurses dedicated to overseeing resuscitation practices and education at the hospital) in the United Kingdom.14 Such a resuscitation officer model adopted by US hospitals could improve quality and intensity of resuscitation care approaches.

Particularly surprising was the high rate of respondents (70%) reporting that they do not utilize any CPR assist technology. In the patient who does not have an arterial line, use of quantitative capnography is the best measure of cardiac output during a cardiac arrest yet only one quarter of hospitals reported using it, with no discrepancy between hospital type or size. A recent summit of national resuscitation experts expounded on the AHA guidelines suggesting that end tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) should be used in all arrests to guide quality of CPR with a goal value of > 20.8 Similarly, CPR feedback devices have an even higher Level of Evidence recommendation in the 2010 AHA guidelines than capnography, yet only 4% of hospitals reported utilizing them. While it is true that introducing these CPR assist technologies into a hospital would require some effort on the part of hospital leadership, it is important to recognize the potential role such devices might play in the larger context of a resuscitation quality program to optimize clinical outcomes from IHCA.

Several differences were noted between hospitals based on teaching status. While all hospitals were more likely to rely on physicians to lead resuscitations, non-teaching hospitals were more likely to report routine leadership by nurses and pharmacists. Non-teaching hospitals were also less likely to have a CPR committee, even after adjusting for hospital size. In addition, these hospitals were also more likely to report the lack of a clinical champion as a barrier to quality improvement.

There were several limitations to this study. First, this was a descriptive survey that was not tied to outcomes. As such, we are unable to draw conclusions about which practices correlate with decreased incidence of cardiac arrest and improved survival. Second, this was an optional survey with a somewhat limited response rate. While the characteristics of the non-responding hospitals were similar to the responding hospitals, we cannot rule out the possibility that a selection bias was introduced, which would likely overestimate adherence to the guidelines. Self-reported responses may have introduced additional errors. Finally, the short interval between the release of the 2010 Guidelines and the administration of the first survey may have contributed to the variability in implementation of some practices, but many of the recommendations had been previously included in the 2005 Guidelines.

We conclude that there is wide variability between hospitals and within practices for resuscitation care. Future work should seek to understand which practices are associated with improved patient outcomes and how best to implement these practices in a more uniform fashion.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nancy Hinckley who championed the study; David Chearo, Christelle Marpaud, and Martha Van Haitsma of the University of Chicago Survey Lab for their assistance in formulating and distributing the survey; and JoAnne Resnic, Nicole Twu and Frank Zadravecz for administrative support.

Financial support: This study was supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine with a grant from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Edelson is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23 HL097157). In addition, she has received research support and honoraria from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), research support from the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway), and an honorarium from Early Sense (Tel Aviv, Israel). Dr. Hunt has received research support from the Laerdal Foundation for Acute Medicine (Stavanger, Norway), the Hartwell Foundation (Memphis, TN) and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation (Jacksonville, FL), and honoraria from the Kansas University Endowment (Kansas City, KS), JCCC (Overland Park, KS) and the UVA School of Medicine (Charlottesville, VA) and the European School of Management (Berlin, Germany). Dr. Mancini is supported in part by an AHRQ grant (R18HS020416). In addition, she has received research support from the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway), and honoraria from Sotera Wireless, Inc. (San Diego, CA). Dr. Abella has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Medtronic Foundation (Minneapolis, MN), and Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA); volunteer activities with the American Heart Association; and honoraria from Heartsine (Belfast, Ireland), Velomedix (Menlo Park, CA), and Stryker (Kalamazoo, MI). Mr. Miller is employed by the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Appendix Figure.

Survey tool.

References

- 1.Girotra S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS. Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012 Nov 15;367(20):1912–1920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merchant RM, Yang L, Becker LB, et al. Incidence of treated cardiac arrest in hospitalized patients in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2011 Nov;39(11):2401–2406. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, et al. Racial differences in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2009 Sep 16;302(11):1195–1201. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA, Nallamothu BK. Hospital variation in time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Jul 27;169(14):1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberger ZD, Chan PS, Berg RA, et al. Duration of resuscitation efforts and survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Lancet. 2012 Oct 27;380(9852):1473–1481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60862-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after inhospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):9–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science. Circulation. 2010;122(18 suppl 3):S640–S946. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meaney PA, Bobrow BJ, Mancini ME, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013 Jul 23;128(4):417–435. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829d8654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Hospital Association [October 11, 2013];AHA Annual Survey. AHA Data Viewer: Survey Instruments. 2008 2012 http://www.ahadataviewer.com/about/hospital-database/.

- 10.Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lomas J, Anderson GM, Domnick-Pierre K, Vayda E, Enkin MW, Hannah WJ. 1989;321(19):1306–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grol R, Grimshaw J. 2003;362(9391):1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabbott D, Smith G, Mitchell S, et al. 2005;13(3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]