Abstract

Comparative analyses of complete chloroplast (cp) DNA sequences within a species may provide clues to understand the population dynamics and colonization histories of plant species. Equisetum arvense (Equisetaceae) is a widely distributed fern species in northeastern Asia, Europe, and North America. The complete cp DNA sequences from Asian and American E. arvense individuals were compared in this study. The Asian E. arvense cp genome was 583 bp shorter than that of the American E. arvense. In total, 159 indels were observed between two individuals, most of which were concentrated on the hypervariable trnY-trnE intergenic spacer (IGS) in the large single-copy (LSC) region of the cp genome. This IGS region held a series of 19 bp repeating units. The numbers of the 19 bp repeat unit were responsible for 78% of the total length difference between the two cp genomes. Furthermore, only other closely related species of Equisetum also show the hypervariable nature of the trnY-trnE IGS. By contrast, only a single indel was observed in the gene coding regions: the ycf1 gene showed 24 bp differences between the two continental individuals due to a single tandem-repeat indel. A total of 165 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were recorded between the two cp genomes. Of these, 52 SNPs (31.5%) were distributed in coding regions, 13 SNPs (7.9%) were in introns, and 100 SNPs (60.6%) were in intergenic spacers (IGS). The overall difference between the Asian and American E. arvense cp genomes was 0.12%. Despite the relatively high genetic diversity between Asian and American E. arvense, the two populations are recognized as a single species based on their high morphological similarity. This indicated that the two regional populations have been in morphological stasis.

Introduction

Approximately 480 complete chloroplast (cp) genome sequences are currently publicly available (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome), the majority of which are derived from economically important crop plants. Comparative analysis of chloroplast sequences indicate that genome structure, gene content, and gene order are largely stable in land plant lineages [1]. However, highly rearranged cp genome structures are observed in some land plant lineages, and can be used as molecular markers to elucidate the ancient divergence of specific groups [2]–[4]. Because of the generally conservative nature of cp genome structure, cp genome data are used most often to address phylogenetic and evolutionary questions at or above the species level. Nevertheless, base substitutions and small indels are seen frequently in cp genomes, even between closely related taxa. [3], [5], [6].

Cp genome comparative analyses were performed using sequences from seed plants in closely related taxa [7]–[9]. For example, 72 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 27 indels were observed when two subspecies of rice (Oryza sativa spp. indica and O. sativa spp. japonica) were compared [7], and 32 SNPs were detected between the cp genomes of 17 Jacobaea vulgaris individuals [9]. The cp genomes of Panicum virgatum, which has different ecotypes in upland and lowland regions, contained 116 SNPs and 46 indels [10], and high variability in indel (3–278) and SNP (6–1000) numbers was noted in the cp genomes of 13 Gossypium species [11]. Finally, comparison of intraspecific variation in rare and widespread pines indicated low levels of divergence [8]. These data improved our understanding of cp genome evolution and divergence times of closely related taxa. Recent advances in rapid pyrosequencing techniques provide further opportunities to study population diversification and evolution using large numbers of whole cp genome sequences.

In monilophytes, a sister group to that of seed plants, no comparative cp genome analyses have been performed in intraspecific taxa despite the availability of seven complete cp genome sequences [12]–[15]. Previous monilophyte cp genome analyses focused on higher taxonomic levels and examined gene content, gene rearrangement, nucleotide substitution, and phylogenetic relationships.

Plant species distribution in different continents is a subject of ongoing interest to botanical researchers. The disjunctive distributions of similar flowering plant species in North America and East Asia have been extensively studied with respect to migration path, migration time, habitat similarity, and phylogenic relationship [16]–[23]. Single fern species are often distributed throughout the two continents. This contrasts with flowering plant distribution, in which the same species rarely occurs in both continents [24], [25]. One example is the Adiantum pedatum complex of leptosprangiate ferns: molecular data suggest that A. pedatum migrated from East Asia to North America through the Bering land-bridge and subsequently migrated from North America to East Asia [25]. Disjunctive distribution within a species is more easily observed in ferns than in flowering plants. Homosporous fern spores are easily dispersible and are able to live independently, facilitating the founding of a new population after migrations up to thousands of kilometers [26].

E. arvense is the most widely distributed fern globally, and is divided into two chemotypes. Plants in the European population do not contain flavonoids, but plants in the Asian and American populations contain luteolin 5-O-glucoside and malonyl ester [27]. However, morphological characteristics do not differ significantly between the three regional E. arvense populations and they are recognized as a single species.

With the exception of a common inversion in monilophytes, the American E. arvense cp genome structure in the large single-copy (LSC) region resembles the cp genome in moss and hornwort. The trnY-trnE intergenic spacer (IGS) region in the American E. arvense cp genome has a distinctive length of 5 kb, unlike in other monilophyte cp genomes. The lengths of trnY-trnE IGS usually less than I kb in other monilophytes [28]. This unusual trnY-trnE IGS length was also detected in E. ramosissimum, and this unique characteristic may be attributable to a repetition of the trnY anticodon loop [29].

In this study, we investigated the differences between the Asian and American E. arvense whole cp genomes. In addition, we analyzed repeat sequences in the trnY-trnE IGS region to determine the origin of the repeating unit that forms a hotspot in the cp genomes of genus Equisetum. Finally, we used the cp genome differences between Asian and American E. arvense to understand correlations between disjunctive distribution and cp genome divergence.

Materials and Methods

Chloroplast genome sequencing and annotation

E. arvense was collected from South Korea (H.-T. Kim, 2009-0413, voucher specimen in Korea University, Seoul (KUS), herbarium) and chloroplasts were separated from fresh leaves using a sucrose step-gradient method [30]. Cp DNAs (PDBK DNA No. 2009-0413) were isolated using 5× lysis buffer [31] and were sequenced using a Genome Sequencer FLX Titanium (Macrogen, Korea). Total FLX read numbers were 123,080, and the average read length was 337.5 bp. Six large contigs covered 90% of the total cp genome sequence. The E. arvense cp genome sequencing strategy was as indicated in Figure S1. Two additional PCR methods were used to fill the 10% gap and low-coverage regions (10%). A long-PCR method was used to fill gaps >3 kb, with conditions as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C, 4 min; (94°C, 15 s; 53–65°C, 30 s; 68°C, 3–10 min)×35 cycles; and post-extension at 72°C, 7 min. A short-PCR method was used to fill gaps <3 kb, with conditions as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C, 4 min; (94°C, 15 s; 50°C, 30 s; 72°C, 2 min)×35 cycles; and post-extension at 72°C, 3 min. PCR products were purified using column-based kits (Qiagen QIAquick PCR purification kit, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced using Big-Dye chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an ABI 3730XL sequencer.

The cp genome sequence of Asian E. arvense was assembled using Sequencher 4.7. Genes were annotated using DOGMA [32], and gene locations were determined by NCBI BLAST search (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Secondary tRNA structures and location of tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE 1.21 [33] Additional bioinformatic analyses were similar to those described in Kim and Lee [34], Lee et al. [3], and Yi and Kim [35].

Comparison of complete cp genome sequences from Asian and American E. arvense

Indels and SNPs between the Asian and American E. arvense (NC_014699) cp genomes were detected as follows. The sequences of the two E. arvense cp genomes were divided into three functional segments (gene coding regions, introns, and intergenic spacers) and the partitioned sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE program [36]. Positions of indels and SNPs were determined using Geneious 5.6.5 [37]. Indels were divided into two types, A and B. Insertion was observed in the Asian E. arvense cp genome sequence for type A indels and in the American E. arvense cp genome for type B indels. Insertion event orientation was determined using E. hyemale and Psilotum nudum cp sequences as references for the outgroup sequence comparison method. A tandem-repeat finder [38] was used to classify indels according to location in 1) mononucleotide repeat regions, 2) tandem-repeat regions, and 3) dispersed repeat regions. The folding structure of the rrn16 gene was predicted using the Mfold Web Server [39]. The rrn16 gene sequences from three eusporangiate ferns and Osmunda cinnamomea were obtained from GenBank (KF 225592, NC 008829, NC 017006, and NC 003386) and were used for folding structure comparisons.

Analysis of trnY-trnE IGS sequences between Equisetum species

Six sequences representing the two Equisetum subgenera [40], [41] were used to analyze differences between species in the trnY-trnE IGS region. Four sequences were obtained from GenBank and two were generated in this study (Table 1). E. hyemale was collected in South Korea (H.-W. Kim 2007-0543, voucher specimen in KUS herbarium) and genomic DNA (PDBK DNA No. 2007-0543, voucher specimen in KUS herbarium) was extracted from fresh leaves using the CTAB method [42]. DNA was purified using cesium chloroide/ethidium bromide gradients. Primers were designed to amplify and sequence the trnY-trnE IGS region of E. hyemale (Forward primer: CAAAGCCAGCGGATTTACAA, Reverse primer: CCCCATCGTCTAGTGGCCTA) using the cp genome sequence of E. arvense as a reference sequence. The long-PCR method was used to amplify the region. Sequences were assembled with Sequencher 4.7 and the locations of the trnY and trnE genes were confirmed using DOGMA. The six trnY-trnE IGS sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE alignment program [36].

Table 1. The list of taxa used in this study.

| Location | Subgenus | Species | GenBank accession # |

| America | Hippochaete | Equisetum hyemale | KC117177a |

| Asia(Korea) | Equisetum hyemale | KC610090b | |

| Asia(China) | Equisetum ramosissimum | HQ658109b | |

| America | Equisetum | Equisetum arvense | NC014699a |

| Asia(Korea) | Equisetum arvense | JN968380a | |

| Asia(china) | Equisetum arvense | HQ658110b |

Repeat sequences in trnY-trnE IGS were analyzed using REPuter [43] with a 10 bp minimum length of repeat sequence and a Hamming value of 3 bp. Repeat sequence frequencies were detected using DNA Pattern Search (http://www.geneinfinity.org/sms/sms_DNApatterns.html#). The formation of repeat sequence hairpin structures was confirmed using the Mfold Web Server [39]. Consensus repeat sequences were numbered by position and sequence frequencies at each position were also calculated. Dot-matrix analysis (Serolis dot-plot software version 0.9.9, available from http://www.code10.info) was used to assess the distribution patterns of repeated units and the conservation levels of each repeat unit in the trnY-trnE IGS region.

Results

Length variation caused by insertions/deletions in two E. arvense cp genomes

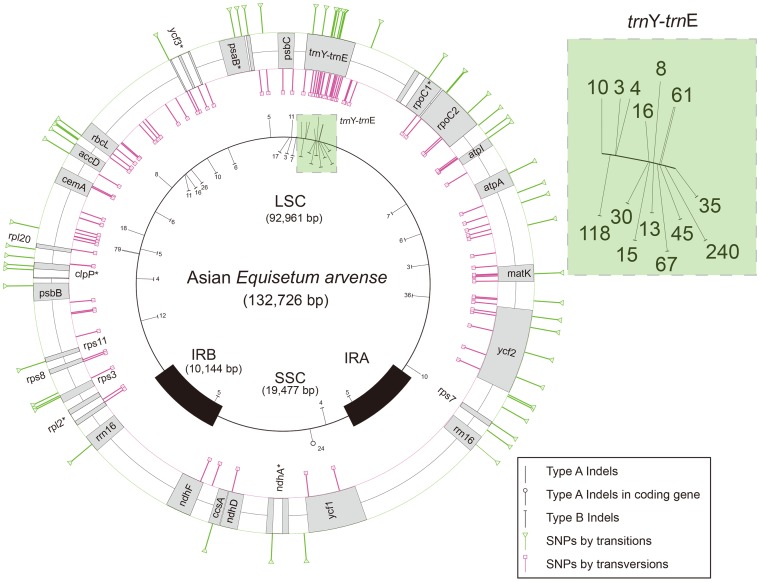

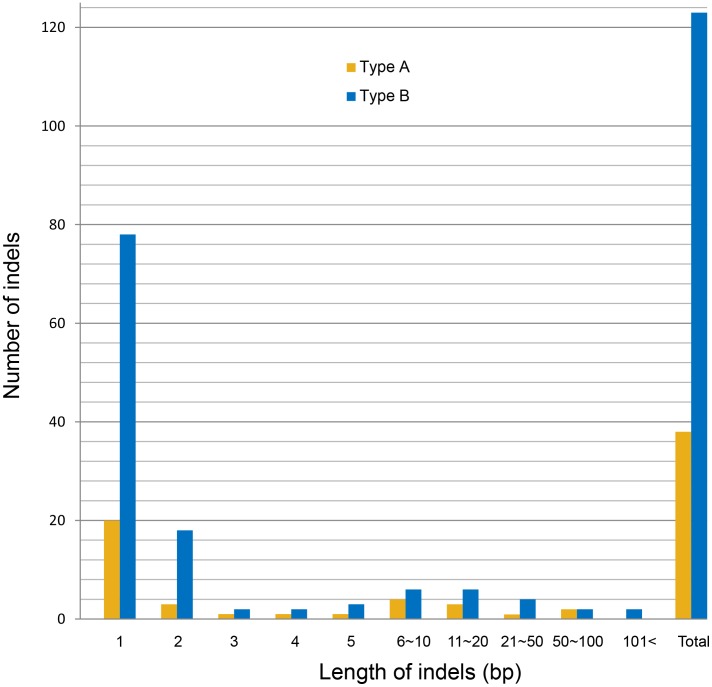

The complete cp genome sequence of Asian E. arvense was 132,726 bp in length, comprising a 92,961 bp LSC region, a 19,477 bp small single-copy (SSC) region, and two 10,144 bp inverted repeats (IRs) (Fig. 1). Comparison of the Asian and American E. arvense cp genomes indicated that the Asian E. arvense cp genome LSC region was 581 bp shorter, the IR region 5 bp shorter, and the SSC region 8 bp longer than in the American E. arvense cp genome (Table 2). Most of the 159 indels (69.2%) occurred in homopolymer regions, and most were type B indels. The remaining indels occurred in tandem-repeat regions and were more than 2 bp in length (15.1%) or were in non-repeat regions (15.7%). Regionally, 142 indels (89.3%) were detected in the LSC region, 13 (8.2%) were detected in the SSC region, and four (2.5%) were detected in the IR regions. The indel number per unit length ratio was 7.7∶3.4∶1 (LSC∶SSC∶IR). All indels were found in noncoding regions with the exception of an indel affecting the ycf1 gene in the SSC region. An insertion of a 24 bp (ATCAATGCTAGATGTTTCAAAAGT) tandem-repeat unit was observed in the ycf1 gene in Asian E. arvense. Most indels (75%) were 1–2 bp in length; these accounted for 15% of the difference in length between the Asian and American E. arvense cp genomes (Fig. 2). Indels ≥3 bp long accounted for 85% of the length difference between the two genomes. The ≥3 bp indels (13 type A and 27 type B) were found throughout the cp genome. A high proportion (35.9%) were concentrated in the trnY-trnE IGS region (Fig. 1), with the remainder evenly distributed across the rest of the cp genome.

Figure 1. Distribution map of indels and SNPs on the cp genomes of Equisetum arvense.

This map was generated by comparing Asian and American E. arvense individuals. Indels ≥3 bp in length are indicated on the inner circle and SNPs are indicated on the outer circle. Genes with SNP(s) are listed on the outer circle. The numeric values on the inner circle indicate the indel length at each location. A gene name annotated with an asterisk indicates an intron-containing gene. Detailed locations of SNPs on relevant gene(s) and IGS region(s) are marked on the outer circle. The green box at the right upper corner shows indel locations and indel length on the trnY-trnE IGS region.

Table 2. Indel events on the cp genomes of Asian and American E. arvense.

| LSC | SSC | IR(×2) | Total | |||||

| Type A | Type B | Type A | Type B | Type A | Type B | Type A | Type B | |

| Indels on homopolymer regions | 17 | 80 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 92 |

| Indels on tandem repeat regions | 6 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 17 |

| Indels on other regions | 11 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 14 |

| total | 34 | 108 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 36 | 123 |

Figure 2. Bar graph showing the number (Y axis) and length (X axis) of indels.

Type B indels were predominant over type A indels (see text).

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in two E. arvense cp genomes

In total, 165 SNPs were detected between the Asian and American E. arvense genomes (Fig. 1). Of these, 155 (93.9%) were found in the LSC region, eight (4.8%) were located in the SSC region, and two (1.2%) were found in the IR regions (Table 3). The SNP number per unit length ratio was 16.8∶4.2∶1 (LSC∶SSC∶IR). Most SNPs (100; 60.6%) were found in IGS, 50 SNPs (30.5%) were located in protein-coding genes, 13 SNPs (7.9%) were in introns, and two SNPs (1.2%) were found in an rRNA gene. Thirty-five SNPs were concentrated in the trnY-trnE IGS region. The SNP in the IR region was detected in the rrn16 gene, and was a unique base substitution reported only in Asian E. arvense (Fig. 3). The putative folding structures of rrn16 due to the SNP are compared in the Figure S2. Of the 50 SNPs found in protein-coding genes, 23 were transitional changes (Ts) and 27 were transversional changes (Tv) (Table 4). Twenty Ts and ten Tv changes were synonymous substitutions (Ks), and three Ts and seven Tv changes were nonsynonymous (Kn). SNPs were detected in 26 of the 84 protein-coding genes. The highest K2P distance was observed for the matK gene, which had five Kn changes. The most substitutions were found in the ycf2 gene, with five Ks and four Kn changes. The Ts/Tv ratio for the whole cp genome was 0.53, while the Ts/Tv ratio for the coding region alone was 0.85. The Ts/Tv ratio in coding regions (0.85) was two-fold higher than the ratio in IGS regions (0.39) and introns (0.41).

Table 3. SNPs on the cp genomes of Asian and American E. arvense.

| Coding regions | IGSs | Introns | rRNAs | Total | ||||||

| Ts | Tv | Ts | Tv | Ts | Tv | Ts | Tv | Ts | Tv | |

| LSC | 21 | 23 | 28 | 71 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 53 | 103 |

| SSC | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| IR(×2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 23 | 27 | 28 | 72 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 57 | 108 |

Ts and Tv indicate transitional and transversional changes, respectively.

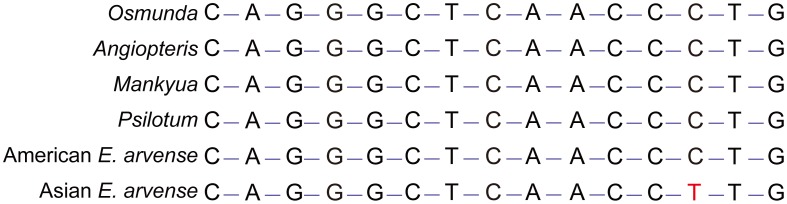

Figure 3. Aligned SNP sequences of the rrn16 gene region.

All eusporangiate ferns and Osmunda cinnamomea, except Asian E. arvense, contained identical sequences. C to T substitution was observed in Asian E. arvense. Ten E. arvense individuals from various locations in Korea, Japan, and China share the C to T substitution.

Table 4. Distribution of nucleotide substitutions on coding genes of the cp genomes of Asian and American E. arvense populations.

| Region | Gene | Ts | Tv | S | N |

| LSC (21 genes) | accD | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| atpA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| atpI | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| cemA | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| clpP | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| matK | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 | |

| psaB | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| psbB | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| psbC | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| rbcL | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| rpl2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| rpl20 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| rpoC1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| rpoC2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| rps11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| rps14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| rps3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| rps7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| rps8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| ycf2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| ycf3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| SSC (5 genes) | ccsA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| ndhA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| ndhD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| ndhF | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| ycf1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Total | 23 | 27 | 30 | 20 |

Hairpin structures in the trnY-trnE IGS in genus Equisetum

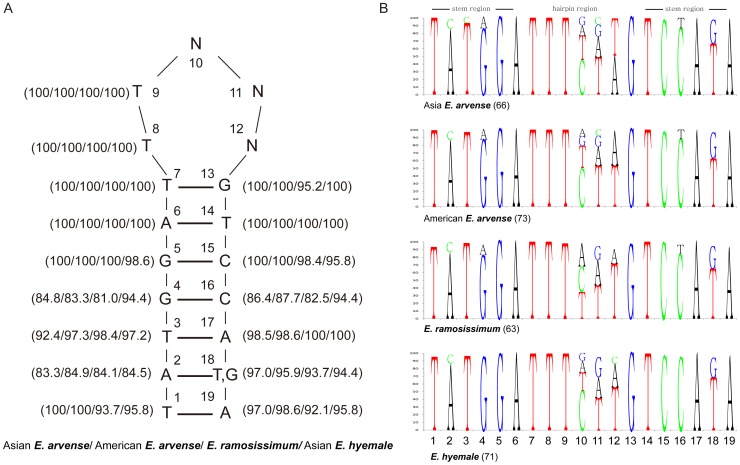

The trnY-trnE IGS was 4,534 bp and 4,991 bp in length in Asian and American E. arvense, respectively. This region comprised only 3.4% of the genome but was responsible for 78% of the total variation in length between the two cp genomes. Several secondary-structure-forming repeats were located in the trnY-trnE IGS region and had a 19 bp basic unit.

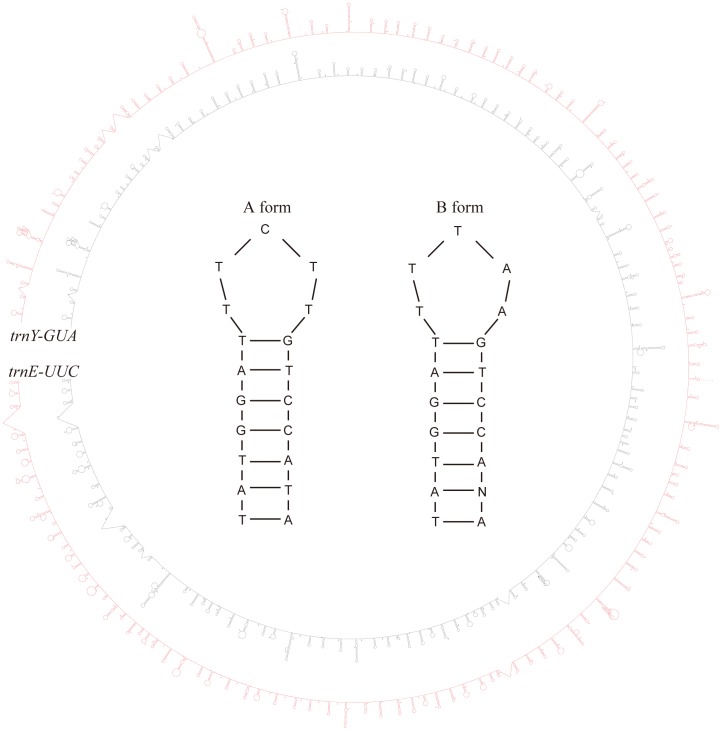

The number of repeats differed between the genomes, with 66 in Asian E. arvense and 73 in American E. arvense. Most of the repeating units were in one of two different sequence forms, A and B. The A-form consisted of a 7 bp stem region (TATGGAT) and a 5 bp loop region (TTCTT). The same stem region (TATGGAT) was observed in the B-form, but a different loop region was present (TTTAA) (Fig. 4). Eighteen A-form and twenty-three B-form repeats were detected in Asian E. arvense, while twenty-eight A-form and twenty-eight B-form repeats were detected in American E. arvnese. Indels greater than 10 bp in length occurred mainly in the stem regions of these hairpin structures and contributed to the variation in length between the Asian and American E. arvense sequences. In addition, two indels were detected between Chinese and Korean individuals of Asian E. arvense, both of which were associated with the A-form repeating unit.

Figure 4. Putative folding structures of trnY-trnE IGS sequences in Asian and American E. arvense.

The inner circle indicates Asian E. arvense sequence and the outer circle indicates American E. arvense sequence. Both sequences had numerous hairpin structures that were largely distributed evenly across the entire region. The most common two hairpin sequences (A and B forms) are shown inside the two circles. The two forms differed mainly on the loop region sequences. The most frequent base at the N position in the stem of the B form was G or T followed by A or C.

Other species from genus Equisetum varied in the length of their trnY-trnE IGS region. These species had similar 19 bp repeating units to those in E. arvense, but sequence units were slightly modified (Fig. 5). E. hyemale and E. ramosissimum had 71 and 63 of the 19 bp repeat units, respectively. These repeating units were highly conserved both in structure and sequence, with a higher level of variation observed in the loop region than the stem region (Fig. 5). Stem region sequences were identical at the positions from 5 to 9 in all individual units with the exception of a single A-T pairing of the 5th–15th bases in E. hyemale. In addition, the 13th, 14th, and 15th bases paired with the 7th, 6th, and 5th bases, respectively, and showed over 95% identity between/among the four species. The 1st–19th and 17th–3rd pairings showed greater than 90% identity between/among the four species.

Figure 5. Consensus sequences for the repeated hairpin structure in the trnY-trnE IGS region.

(A) The most common consensus 19 bp sequences and frequencies were as indicated on the hairpin structure. Positions 6, 7, 8, 9, and 14 were invariable and positions 10, 11, and 12 were the most variable sites. (B) Consensus sequences were derived from the 66 repeats of Asian E. arvense, the 73 repeats of American E. arvense, the 63 repeats of E. ramosissimum, and the 71 repeats of E. hyemale.

The 2nd base was most frequently A (83–85%), while the 18th position was usually T (63–69%). C was occasionally found at the 2nd base position (11–12%), and G was sometimes at the 18th base position (25–32%). Three main base-pairings were observed between the 2nd and 18th base positions: A-T had the highest frequency, followed by A-G and C-G pairs. The 10th, 11th, and 12th bases were hypervariable sites, and the main nucleotides at these positions varied according to species. For example, CTT was the main sequence in subgenus Equisetum. In subgenus Hippochaete, however, ATT was predominant in E. ramosissimum but CTT was the main sequence found in E. hyemale.

The total sequence lengths in the two species from the subgenus Hippochaete were longer than the sequences from two E. arvnese of subgenus Equisetum. We calculated the p-distance and the number of differences in the trnY-trnE IGSs between the species (Table 5). The intraspecific p-distances between E. hyemale and the two continental individuals of E. arvense were both 0.008. The distance between the two Asian individuals was 0.0004. The interspecific p-distances in subgenus Hippochaete (E. hyemale and E. ramosissimum) were in the range 0.031–0.034. The interspecific p-distances between the two subgenera (subgenus Hippochaete and subgenus Equisetum) were in the range 0.084–0.096. The lowest interspecific p-distance value was observed between Korean E. arvense and American E. hyemale and the highest value was seen between E. ramosissimum and American E. arvense.

Table 5. No. of nucleotide differences and p-distances of the trnY-trnE IGS region in genus Equisetum.

| Korean E. arvense | Chinese E. arvense | American E. arvense | Korean E. hyemale | American E. hyemale | E. ramosissimum | |

| Korean E. arvense (4534 bp) | - | 2 | 35 | 351 | 333 | 360 |

| Chinese E. arvense (4872 bp) | 0.0004 | - | 38 | 378 | 369 | 375 |

| American E. arvense (4991 bp) | 0.008 | 0.008 | - | 397 | 356 | 385 |

| Korean E. hyemale (5400 bp) | 0.090 | 0.092 | 0.095 | - | 44 | 147 |

| American E. hyemale (5645 bp) | 0.084 | 0.089 | 0.084 | 0.008 | - | 159 |

| E. ramosissimum (5000 bp) | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.096 | 0.031 | 0.034 | - |

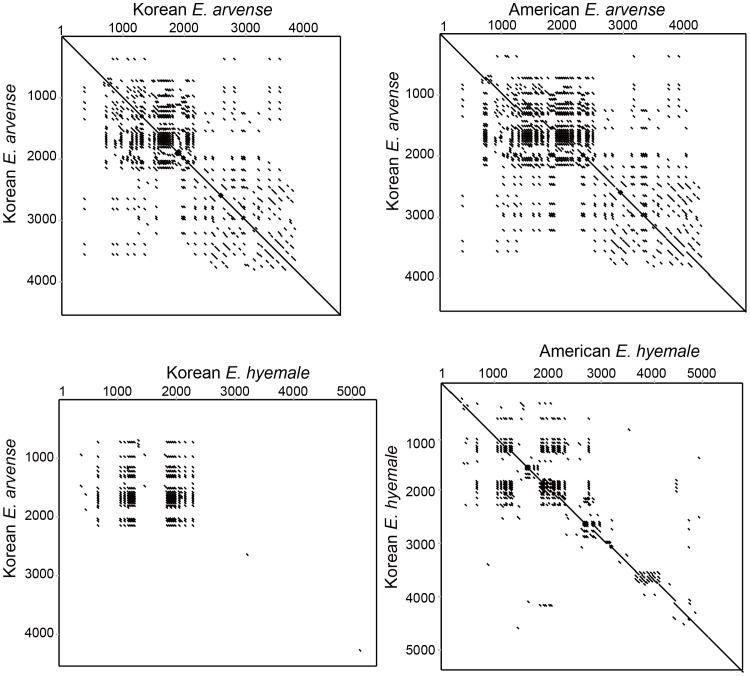

Dot-plot analysis of Korean E. arvense indicated that repeating units were widespread and concentrated in the first half of the trnY-trnE IGS region (Fig. 6). A similar pattern was observed with dot-plot analysis of Asian and American E. arvense. A few repeat units were found in the second half of the trnY-trnE IGS region in E. arvense and E. hyemale. E. arvense and E. hyemale had many similar repeat units, and these were located primarily in the 800 to 2,200 bp region. Overall, repeat unit conservation was more prominent in the first half of the IGS than the second half.

Figure 6. Dot matrix showing the occurrence, conservation, and divergence of the repeating units in the trnY-trnE IGS region.

The region proximal to the trnY gene (1–2,200 bp region) had high density and conservation of repeating sequences compared to the region proximal to the trnE gene (>2,200 bp region).

Discussion

Molecular evolution of the cp genome in Asian and American E. arvense

The Asian and American E. arvense cp genomes were of different lengths, and this variation was due to the presence of 159 indels. The majority of the indels were homopolymer length variants; however, these can be produced as artifacts of the 454-sequencing process [44], [45]. Nevertheless, we were confident of the accuracy of our complete sequences for three reasons. First, our pyrosequencing contigs covered the majority of specific sequences with 100× coverage and the majority consensus sequences were derived from numerous overlapping contigs. Second, we manually amplified and sequenced low-coverage regions and found many homo- and heteropolymer repeating regions. Third, the cp genome of the Olea europaea complex had approximately 4–8× more 1–2 bp indels than >3 bp indels [46], whereas the ratio of 1–2 bp to >3 bp indels in E. arvense was 3∶1. If the E. arvense indels were identified mainly as a result of 454-pyrosequencing errors, the indel ratio would be biased towards 1–2 bp rather than >3 bp indels. Therefore, we believe that the majority of the homopolymer indels found in E. arvense were true indels that reflected the evolutionary history of the two continental individuals.

Relatively few large indels (>3 bp) were previously observed in closely related taxa of plant genera. For example, only seven indels were reported in the cp genomes of the O. europaea complex. Nine indels were observed in three species of Phyllostachys and 3–21 indels were reported in Gossypium species. No indels were detected between the two cp genomes of Nicotiana tabacum and N. sylvestis. By contrast, 40 indels of >3 bp were seen in Asian and American E. arvense despite the recognition of these two continental populations as a single species. In this study, we excluded 14 indels that were identified from the hypervariable trnY-trnE region of the Equisetum cp genome. Therefore, our data clearly indicated that the variation between the cp genomes of the two E. arvense was much higher than the intersubspecific or the interspecific differences observed in various flowering plants. The high intraspecific difference observed between the two continental E. arvense was also confirmed by SNP analysis.

SNP variation between Asian and American E. arvense was 0.12%. This variation level was higher than intraspecific or interspecific differences previously reported in numerous seed plants, with intraspecific SNP variation being very low in many plant groups. For example, SNP variation was 0.07% between two interecotypes of Panicum virgatum [10], and was 0.02% between 17 individuals of Jacobaea vulgaris [9]. In addition, SNP variation was 0.05% between Oryza sativa subsp. indica and O. sativa subsp. japonica [7] and 0.03–0.07% in the Olea europaea complex [46]. The SNP variation between E. arvense individuals was higher than interspecific variation observed in several cases. Variation was 0.003% between Nicotiana tabacum and N. sylvestis, 0.007–0.11% between five Gossypium species [11], and 0.02–0.05% between three Phyllostachys species [47]. In addition to the substantial indel and SNP differences between Asian and American E. arvense, the genetic distance between the two E. arvense individuals was higher than the interspecific variation in flowering plants. The high genetic diversity and low morphological diversity indicated that the two continental E. arvense populations had high genetic heterogeneity while being in morphological stasis.

A few examples of regionally isolated flowering plant species in similar habitats exhibiting similar morphological characteristics have been reported [19], [48]. The two continental populations of E. arvense experience similar habitats and have no morphological differences, yet are geographically isolated in Asia and North America. This suggested that the cp genomes would differ considerably as the two E. arvense populations were split by disjunctive distribution. The high variance between the cp genomes of the two continental E. arvense suggests relatively ancestral divergence if a molecular clock concept is applied.

To estimate the divergence time between Asian and American E. arvense, we adopted different SNP data from five data sets. The whole cp SNP data between the two inter-subspecies of Oryza sativa (ssp. indica and ssp. japonica) and two ecotypes of P. virgatum were used. The divergence time of the two O. sativa inter-subspecies was estimated at 0.4 mya [50], and the divergence time of the two P. virgatum eocotypes was estimated at 0.7–1.0 mya [51]. SNP variation between the two E. arvense was 2.3× higher than between the two O. sativa inter-subspecies and 1.5× higher than between the two P. virgatum eocotypes. This suggested that the two E. arvense populations diverged 1.0–1.7 mya. We also estimated the divergence time of the two E. arvense populations using the partial and whole cp SNP data from the same Equisetum genus using a published calibration clock [49]. There are three different data sets available from Equisetum. First, the rbcL calibration clock suggested that subgenus Equisetum and subgenus Hypochaete diverged approximately 28.5±5.5 mya. Differences in rbcL between the two E. arvense were 15× lower than between two subgenera of Equisetum. Therefore, the rbcL calibration clock suggested that the two E. arvense populations diverged approximately 1.9±0.4 mya. Second, the hypervariable trnY-trnE intergenic spacer different between the two subgenus Equisetum and subgenus Hypochaete was 9.1% (Table 5) and they diverged approximately 28.5±5.5 mya. Differences in the hypervariable trnY-trnE intergenic spacer between the two E. arvense were 11.4× lower than between two subgenera of Equisetum. Therefore, the hypervariable trnY-trnE intergenic spacer data suggested that the two E. arvense populations diverged approximately 2.5±0.5 mya. Third, the cp SNP difference between the subgenus Equisetum (E. arvense) and subgenus Hypochaete (E. hyemale) was 1.44% and they diverged approximately 28.5±5.5 mya as in the rbcL calibration. Differences in the whole cp SNP between the two E. arvense were 12× lower than between two subgenera of Equisetum. Therefore, the whole cp SNP calibration suggested that the two E. arvense populations diverged approximately 2.4±0.5 mya. The five independent estimates of divergence time are relatively concordant and fall into an overlapping range. However, we are more confident to the Equisetum calibration than the Poaceae calibration because of two reasons. First, the Equisetum clock is based upon abundant fossil records. Second, the Equisetum calibration uses data from the same lineages, minimizing the lineage bias effect of the molecular clock.

Phylogenetic analysis of genus Equisetum estimated the speciation time of E. arvense to be 2.588 mya, which lies between the Pliocene and Quaternary periods [49]. E. arvense may have migrated from one region to another through the Bering land-bridge after speciation, in a similar manner to the migration that produced the Asian and North American Adiantum pedatum complexes. Japanese A. pedatum and northeastern American A. pedatum diverged 2.47 mya. Northeastern American A. pedatum and Chinese A. pedatum subsequently diverged 1.09 mya [25]. The disjunctive distribution of northeastern American A. pedatum and Chinese A. pedatum through the Bering land-bridge in the mid-Pleistocene is very similar to the scenario for the disjunctive distribution of Asian and American E. arvense. Therefore, we believe that E. arvense and A. pedatum might have migrated during the same period, stimulated by the geological or environmental conditions at that time. The molecular differences therefore accumulated between the two continental E. arvense populations since the mid-Pleistocene, 1.9–2.9 mya, with almost no corresponding development of morphological differences.

One rRNA SNP in Asian E. arvense was of particular interest because it was shared by all the Asian individuals, suggesting a single origin for all the Asian individuals. E. arvense is a member of the eusporangiate ferns, which is the basal ferns lineage. Other eusporangiate ferns (Mankyua chejuense, Psilotum nudum and Angiopteris evecta) and basal leptosporangiate fern (Osmunda cinamomea) share the same rRNA sequence as American E. arvense (Fig. 3B). The CCCUG sequence in the rrn16 gene of eusporangiate ferns, including American E. arvense and O. cinamomea, produces a hairpin structure by pairing with CAGGG (Fig. 3). However, in the rrn16 gene of Asian E. arvense, the CCCUG sequence was mutated (to CCUUG) and the CCUUG sequence was paired with CAGGG. Therefore, the rrn16 gene of Asian E. arvense had a less stable folding structure than the equivalent American E. arvense sequence (Figure S2). The SNP in the rrn16 gene therefore changed the minimum free energy for RNA secondary structure. We tested for this SNP using PCR-sequencing techniques in ten Asian E. arvense individuals from Korea, Japan, and China. All Asian individuals shared this SNP.

Repeat sequence evolution in genus Equisetum

Eusporangiate ferns consist of four orders, including Equisetales [52], and the cp genome of one or two species from each order has been sequenced [13], [28], [53]. However, the trnY-trnE IGS expanded up to 5 kb in Equisetum and the duplication of a 19 bp repeating unit was responsible for this expansion. The 19 bp repeating unit was not detected in the cp genomes of the other three orders. This indicated that the 19 bp repeating unit might be a unique molecular characteristic that only occurred in the monotypic genus Equisetum. The genus Equisetum is divided into two subgenera and the 19 bp repeating units with hairpin structures were identified in both. The sequence identity of the 19 bp unit was sufficiently conserved to allow easy recognition. We therefore assumed that the consensus repeating unit originated prior to the separation of the two subgenera in genus Equisetum. Similar expansion of the trnY-trnE IGS (albeit shorter; ∼450 bp) was reported in the leptosporangiate fern Vanderboschia radicans. In that case, duplication of a 27 bp repeat unit homologous to a trnY anticodon was responsible for the expansion of the trnY-trnE IGS [29]. A similar duplicated expansion of trnD-trnY IGS was responsible for length variation in Pseudotsuga species (Gymnosperms) [54]. We compared the Equisetum trnY-trnE IGS repeat unit to those in other species but were unable to conclusively determine the origin of the 19 bp repeat unit in Equisetum trnY-trnE IGS as sequence identity with trnY was low. Gao et al. [29] suggested that a 13 bp repeat in the Equisetum trnY-trnE IGS may be derived from partial trnY sequences. However, our data do not support this as the extended stem region in our 19 bp consensus repeat unit is substantially different from trnY anticodon sequences. Several cp trn genes hold similar sequence components and it is therefore difficult to deduce the origin of the trn repeat unit. Furthermore, the trnY duplication occurs at slightly different locations in Pseudotsuga and V. radicans. Pseudotsuga, Equisetum, and V. radicans are not phylogenetically close and no known trnY-trnE IGS expansions have occurred in the sister groups of these three lineages. Therefore, we believe that the trnY-trnE IGS expansions in Pseudotsuga, Equisetum and V. radicans were independent parallel evolutionary events rather than a homologous synapomorphy. By contrast, the trnY-trnE IGS expansion was discovered in all Equisetum species examined in this study and is a single evolutionary event.

Fossils of the genus Equisetites, which is the most closely related genera to genus Equisetum [55], were discovered worldwide in Europe [56], North America [57], Antarctica [58], China [59], and New Zealand [60] in underlying strata of the post-Mesozoic era. This suggested that the divergence time for genus Equisetum was in the Tertiary period. Extant Equisetum species diverged more recently than the Miocene period [49]. Therefore, we reasoned that the repeating units were formed during the Miocene period after or before the formation of genus Equisetum, and the repeating units then spread widely and diverged alongside Equisetum speciation events. To summarize, the 19 bp repeating unit is a synapomorphic molecular characteristic shared by all living members of Equisetum.

The trnY-trnE IGS region differed in length between Korean and Chinese E. arvense individuals. Chinese E. arvense had 76 repeat sequences and a trnY-trnE IGS length of 4,872 bp. When repeat sequence numbers and trnY-trnE IGS lengths were compared, Chinese E. arvense was more superficially similar to American E. arvense than to Korean E. arvense. However, when the indel and SNP patterns were considered together, Chinese E. arvense was found to be more closely related to Korean E. arvense than to American E. arvense. Two large indels (241 bp, 97 bp) and two SNPs were detected between Korean E. arvense and Chinese E. arvense, but 19 indels and 38 SNP differences were noted between the Chinese and American E. arvense individuals.

The difference in the number of repeating units observed in Korean E. arvense and Chinese E. arvense suggested unequal crossover on the tandem-repeat regions. Two unequal crossovers may have generated the large length difference between the Korean and Chinese E. arvense individuals. The two large indels, composed of 241 bp and 97 bp, contained six and three 19 bp repeating units, respectively. Small indels of 1–10 bp were not found between Korean and Chinese E. arvense. In contrast to the large indels, the large numbers of small indels observed between Korean and American E. arvense suggested that the majority of small indels originated as mutation events formed by slipped strand mispairing [61]. A few indels with long length differences were observed between Korean and American E. arvense.

Analysis of the 19 bp repeat sequence (TATGGATTTCTTGTCCATA) (Fig. 5), suggested that the original source sequence was the trnY-trnE IGS. The 19 bp sequence found in this study is 6 bp longer than the trnY anticodon partial sequence proposed as the repeating unit origin [29]. Additionally, the 19 bp sequence had higher similarities than the 13 bp consensus sequence of the trnY anticodon loop region suggested in previous studies [29]. Our 19 bp consensus sequence was based on the wide range of sequence data available for the diverse Equisetum taxa. The expected origin sequence of repeating units was commonly abundant not only in subgenus Equisetum but also in subgenus Hippochaete. In E. ramosissimum, of subgenus Hippochaete, the repeating unit of TATGGATTTATTGTCCATA, which differed from the E arvense consensus at the 10th position (C to A), was found at a slightly higher frequency than the TATGGATTTCTTGTCCATA sequence.

The 11th and 12th sites, located in the hairpin loop region, showed A to T substitutions. Substitutions, albeit rare, were also observed at the 2nd, 4th, 16th, and 18th sites of the stem region. This indicated that the 19 bp repeating units have mutated constantly and maintained evolutionary heterogeneity in the genus Equisetum. Heterogeneity of the repeating unit was confirmed by dot-plot analysis (Fig. 6). The first half of the trnY-trnE IGS had more conserved repeating units than the second half. When compared with the length of the trnY-trnE IGS in other eusporangiate ferns, it was apparent that many repeats occurred in the second half of trnY-trnE IGS, but no apparent homologous repeating sequences were observed between E. arvense and E. hyemale. Therefore, we assumed that the progression to heterogeneity in the repeating unit proceeded particularly rapidly in the second half of the trnY-trnE IGS.

Conclusions

Molecular clock analysis suggested that E. arvense migrated between two continents via the Bering land-bridge 1.9–2.9 mya. After migration, its morphological characteristics remained largely unchanged in each region due to adaption to similar habitats, but constant mutational events occurred in the cp genomes. This indicated that the two continental populations of E. arvense have been in prolonged morphological stasis while the cp genome sequences in the two regions have changed continuously since population dispersal. The levels of sequence and indel divergence between the two regional cp genomes were far higher than those of closely related interspecific taxa in many seed plants. Two regional genotypes can therefore be recognized. Rigorous comparative analyses of the whole cp genomes from multiple accessions of each continental population, including European populations, are needed to comprehensively address population history and the validity of the species boundary.

The trnY-trnE IGS is a hypervariable region within the E. arvense cp genome, and many indel events and SNPs were concentrated in this region. A unique 19 bp repeating sequence unit that formed a hairpin structure was replicated many times in this IGS region and was responsible for the dynamic sequence evolution of the cp genome. The genus Equisetum is a monotypic genus in Equisetales and the repeating units did not exist in other eusporangiate ferns. It was therefore challenging to find the exact origin sequence and to explain the evolutionary paths of repeat unit evolution. A comprehensive study involving additional Equisetum species is needed to understand the evolution of repeat units in the genus. However, with the current limited data set, the region showed very different intraspecific, interspecific, and intersubgeneric p-distance values. Therefore, the hypervariable trnY-trnE IGS region may be a useful molecular marker to study the evolution and phylogeny of Equisetum.

Supporting Information

Sequencing strategy for the E. arvense chloroplast genome. The outer blue circle indicates the sequence region generated by next –generation sequencing (NGS). Seven large NGS contigs cover approximately 90% of the genome. The green broken lines indicate the regions sequenced by PCR amplifications and Sanger sequencing. The trnY-trnE IGS was amplified by long-range PCR methods. The genome map in the inner circle was generated in OrganellarGenomeDRAW [62] after the completion of sequencing and annotation.

(TIF)

The RNA folding structure differences of rrn16 gene from two E. arvense populations. The gray box regions indicated the folding structure differences due to the SNP(C-U). The sequence -CCCUG- paired with the sequence –CAGGG- and form a hairpin structure in the American E. arvense (left). However, the sequence –CCUUG- paired with the sequence –CAAGG- and form a distinct stem structure in the Korean E. arvense (left). Two contrasting folding structures are based on the minimum free energy only. Other alternate folding structures are also possible if we consider other factors affecting the secondary structures.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions for improving the manuscript. All DNA materials used in this study are deposited in the Plant DNA Bank of Korea (PDBK) and are available from the PDBK.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a research grant (#KRF-2010-0011796) from the Korea Research Foundation and by research grants (#062-091-078, #416-111-005) from KEITI to Ki-Joong Kim. A Ph.D. fellowship to HTK was granted by the graduate student education program from NIBR (2012–2013). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jansen RK, Ruhlman TA (2012) Plastid Genomes of Seed Plants. In: R. Bock and V. Knoop, editors. Genomics of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria. Springer Netherlands. pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cosner ME, Raubeson LA, Jansen RK (2004) Chloroplast DNA rearrangements in Campanulaceae: phylogenetic utility of highly rearranged genomes. BMC Evol Biol 4: 27 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/4/27 Accepted 23 August 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee HL, Jansen RK, Chumley TW, Kim KJ (2007) Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of Jasminum and Menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1161–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saski C, Lee SB, Fjellheim S, Guda C, Jansen RK, et al. (2007) Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Hordeum vulgare, Sorghum bicolor and Agrostis stolonifera, and comparative analyses with other grass genomes. Theor Appl Genet 115: 571–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Funk HT, Berg S, Krupinska K, Maier UG, Krause K (2007) Complete DNA sequences of the plastid genomes of two parasitic flowering plant species, Cuscuta reflexa and Cuscuta gronovii. BMC Plant Biol 7: 45 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2229/7/45 Accepted 22 August 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yi DK, Lee HL, Sun BY, Chung MY, Kim KJ (2012) The complete chloroplast DNA sequence of Eleutherococcus senticosus (Araliaceae); comparative evolutionary analyses with other three asterids. Mol Cells 33: 497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tang J, Xia H, Cao M, Zhang X, Zeng W, et al. (2004) A comparison of rice chloroplast genomes. Plant Physiol 135: 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whittall JB, Syring J, Parks M, Buenrostro J, Dick C, et al. (2010) Finding a (pine) needle in a haystack: chloroplast genome sequence divergence in rare and widespread pines. Mol Ecol 19 Suppl 1: 100–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doorduin L, Gravendeel B, Lammers Y, Ariyurek Y, Chin AWT, et al. (2011) The Complete Chloroplast Genome of 17 individuals of Pest Species Jacobaea vulgaris: SNPs, microsatellites and barcoding markers for population and phylogenetic studies. DNA Res 18: 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young HA, Lanzatella CL, Sarath G, Tobias CM (2011) Chloroplast Genome Variation in Upland and Lowland Switchgrass. Plos One 6: e23980 Available: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0023980 Accessed 1 August 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu Q, Xiong G, Li P, He F, Huang Y, et al. (2012) Analysis of complete nucleotide sequences of 12 Gossypium chloroplast genomes: origin and evolution of allotetraploids. PLoS One 7: e37128 Available: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0037128. Accessed 16 April 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wolf PG, Rowe CA, Sinclair RB, Hasebe M (2003) Complete nucleotide sequence of the chloroplast genome from a leptosporangiate fern, Adiantum capillus-veneris L. DNA Res 10: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roper JM, Hansen SK, Wolf PG, Karol KG, Mandoli DF, et al. (2007) The complete plastid genome sequence of Angiopteris evecta (G. Forst.) Hoffm. (Marattiaceae). Am Fern J 97: 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gao L, Yi X, Yang YX, Su YJ, Wang T (2009) Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a tree fern Alsophila spinulosa: insights into evolutionary changes in fern chloroplast genomes. BMC Evol Biol 9: 130 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/9/130 Accepted 11 June 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolf PG, Der JP, Duffy AM, Davidson JB, Grusz AL, et al. (2011) The evolution of chloroplast genes and genomes in ferns. Plant Mol Biol 76: 251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tiffney BH (1985) Perspectives on the origin of the floristic similarity between eastern Asia and eastern North America. J Arnold Arboretum 66: 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Qiu YL, Chase MW, Parks CR (1995) A chloroplast dna phylogenetic study of the eastern Asia eastern North America disjunct section Rytidospermum of Magnolia (Magnoliaceae). Am J Bot 82: 1582–1588. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiang QY, Soltis DE, Soltis PS (1998) The eastern Asian and eastern and western North American floristic disjunction: Congruent phylogenetic patterns in seven diverse genera. Mol Phylogenet Evol 10: 178–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wen J (1999) Evolution of eastern Asian and eastern north American disjunct distributions in flowering plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 30: 421–455. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xiang QY, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Manchester SR, Crawford DJ (2000) Timing the eastern Asian-eastern north American floristic disjunction: molecular clock corroborates paleontological estimates. Mol Phylogenet Evol 15: 462–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wall WA, Douglas NA, Xiang QY, Hoffmann WA, Wentworth TR, et al. (2010) Evidence for range stasis during the latter Pleistocene for the Atlantic Coastal Plain endemic genus, Pyxidanthera Michaux. Mol Ecol 19: 4302–4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wen J (2001) Evolution of eastern Asian-eastern north American biogeographic disjunctions: A few additional issues. Int J Plant Sci 162: S117–S122. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li H-L (1952) Floristic relationships between eastern Asia and eastern north America. Trans Am Philoso Soc 42: 371–429. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato M (1993) Biogeography of ferns - dispersal and vicariance. J Biogeogr 20: 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lu JM, Li DZ, Lutz S, Soejima A, Yi TS, et al. (2011) Biogeographic disjunction between eastern Asia and north America in the Adiantum Pedatum complex (Pteridaceae). Am J Bot 98: 1680–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wolf PG, Schneider H, Ranker TA (2001) Geographic distributions of homosporous ferns: does dispersal obscure evidence of vicariance? J Biogeogr 28: 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Veit M, Geiger H, Czygan FC, Markham KR (1990) Malonylated flavone 5-O-Glucosides in the barren sprouts of Equisetum arvense. Phytochemistry 29: 2555–2560. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karol KG, Arumuganathan K, Boore JL, Duffy AM, Everett KDE, et al. (2010) Complete plastome sequences of Equisetum arvense and Isoetes flaccida: implications for phylogeny and plastid genome evolution of early land plant lineages. BMC Evol Biol 10: 321 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/321. Accepted 23 October 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao L, Zhou Y, Wang ZW, Su YJ, Wang T (2011) Evolution of the rpoB-psbZ region in fern plastid genomes: notable structural rearrangements and highly variable intergenic spacers. BMC Plant Biol 11: 64 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2229/11/64. Accepted 13 April 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palmer JD (1986) Isolation and structural analysis of chloroplast DNA. Methods Enzymol 118: 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jansen RK, Raubeson LA, Boore JL, dePamphilis CW, Chumley TW, et al. (2005) Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Method Enzymol 395: 348–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL (2004) Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20: 3252–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lowe TM, Eddy SR (1997) tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim KJ, Lee HL (2004) Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res 11: 247–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yi DK, Kim KJ (2012) Complete chloroplast genome sequences of important oilseed crop Sesamum indicum L. Plos One 7: e35872 Available: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0035872. Accepted 23 March 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, et al. (2012) Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Benson G (1999) Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zuker M (2003) Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hauke RL (1963) A taxonomic monograph of the genus Equisetum subgenus Hippochaete. J. Cramer. Beihefte Nova Hedwigia 8: 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hauke RL (1978) Taxonomic monograph of Equisetum subgenus Equisetum. Nova Hedwigia 30: 385–455. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1987) A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull 19: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, et al. (2001) REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 4633–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wicker T, Schlagenhauf E, Graner A, Close TJ, Keller B, et al. (2006) 454 sequencing put to the test using the complex genome of barley. BMC Genomics 7: 275 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/7/275. Accepted 26 October 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gilles A, Meglecz E, Pech N, Ferreira S, Malausa T, et al. (2011) Accuracy and quality assessment of 454 GS-FLX Titanium pyrosequencing. BMC Genomics 12: 245 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/12/245. Accepted 19 May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mariotti R, Cultrera NGM, Diez CM, Baldoni L, Rubini A (2010) Identification of new polymorphic regions and differentiation of cultivated olives (Olea europaea L.) through plastome sequence comparison. BMC Plant Biol 10: 211 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2229/10/211. Accepted 24 September 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang YJ, Ma PF, Li DZ (2011) High-throughput sequencing of six bamboo chloroplast genomes: phylogenetic implications for temperate woody bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae). PLoS One 6: e20596 Available: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0020596. Accepted 5 May 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hoey MT, Parks CR (1991) Isozyme Divergence between Eastern Asian, North-American, and Turkish Species of Liquidambar (Hamamelidaceae). Am J Bot 78: 938–947. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Des Marais DL, Smith AR, Britton DM, Pryer KM (2003) Phylogenetic relationships and evolution of extant horsetails, equisetum, based on chloroplast DNA sequence data (rbcL and trnL-F). Int J Plant Sci 164: 737–751. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhu Q, Ge S (2005) Phylogenetic relationships among A-genome species of the genus Oryza revealed by intron sequences of four nuclear genes. New Phytol 167: 249–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morris GP, Grabowski PP, Borevitz JO (2011) Genomic diversity in switchgrass (Panicum virgatum): from the continental scale to a dune landscape. Mol Ecol 20: 4938–4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith AR, Pryer KM, Schuettpelz E, Korall P, Schneider H, et al. (2006) A classification for extant ferns. Taxon 55: 705–731. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grewe F, Guo WH, Gubbels EA, Hansen AK, Mower JP (2013) Complete plastid genomes from Ophioglossum californicum, Psilotum nudum, and Equisetum hyemale reveal an ancestral land plant genome structure and resolve the position of Equisetales among monilophytes. BMC Evol Biol 13: 8 Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/8. Accepted 7 January 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hipkins VD, Marshall KA, Neale DB, Rottmann WH, Strauss SH (1995) A mutation hotspot in the chloroplast genome of a conifer (Douglas-Fir, Pseudotsuga) Is caused by variability in the number of direct repeats derived from a partially duplicated transfer rna gene. Curr Genet 27: 572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schaffner JH (1930) Geographic distribution of the species of Equisetum in relation to their phylogeny. Am Fern J 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kelber KP, van Konijnenburg-van Cittert JHA (1998) Equisetites arenaceus from the Upper Triassic of Germany with evidence for reproductive strategies. Rev Palaeobot Palyno 100: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 57. DiMichele WA, Van Konijnenburg-Van Cittert JH, Looy CV, Chaney DS (2005) Equisetites from the early Permian of north central Texas. The Nonmarine Permian 30: 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cantrill DJ, Hunter MA (2005) Macrofossil floras of the Latady Basin, Antarctic Peninsula. New Zeal J Geol Geop 48: 537–553. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang ZQ (1996) Recovery of vegetation from the terminal Permian mass extinction in North China. Rev Palaeobot Palyno 91: 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- 60. McQueen D (1954) Upper Paleozoic plant fossils from South Island, New Zealand. Trans, roy Soc NZ 82: 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Levinson G, Gutman GA (1987) Slipped-Strand Mispairing - a Major Mechanism for DNA-Sequence Evolution. Mol Biol Evol 4: 203–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lohse M, Drechsel O, Bock R (2007) OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr Genet 52: 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequencing strategy for the E. arvense chloroplast genome. The outer blue circle indicates the sequence region generated by next –generation sequencing (NGS). Seven large NGS contigs cover approximately 90% of the genome. The green broken lines indicate the regions sequenced by PCR amplifications and Sanger sequencing. The trnY-trnE IGS was amplified by long-range PCR methods. The genome map in the inner circle was generated in OrganellarGenomeDRAW [62] after the completion of sequencing and annotation.

(TIF)

The RNA folding structure differences of rrn16 gene from two E. arvense populations. The gray box regions indicated the folding structure differences due to the SNP(C-U). The sequence -CCCUG- paired with the sequence –CAGGG- and form a hairpin structure in the American E. arvense (left). However, the sequence –CCUUG- paired with the sequence –CAAGG- and form a distinct stem structure in the Korean E. arvense (left). Two contrasting folding structures are based on the minimum free energy only. Other alternate folding structures are also possible if we consider other factors affecting the secondary structures.

(TIF)