Abstract

Background

To examine (1) changes in parent (global psychological distress, trait anxiety) and family (dysfunction, burden) functioning following 12 weeks of child-focused anxiety treatment, and (2) whether changes in these parent and family factors were associated with child's treatment condition and response.

Methods

Participants were 488 youth ages 7–17 years (50% female; mean age 10.7 years) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for social phobia, separation anxiety, and/or generalized anxiety disorder, and their parents. Youth were randomly assigned to 12 weeks of “Coping Cat” individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), medication management with sertraline (SRT), their combination (COMB), or medication management with pill placebo (PBO) within the multisite Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study (CAMS). At pre- and posttreatment, parents completed measures of trait anxiety, psychological distress, family functioning, and burden of child illness; children completed a measure of family functioning. Blinded independent evaluators rated child's response to treatment using the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement Scale at posttreatment.

Results

Analyses of covariance revealed that parental psychological distress and trait anxiety, and parent-reported family dysfunction improved only for parents of children who were rated as treatment responders, and these changes were unrelated to treatment condition. Family burden and child-reported family dysfunction improved significantly from pre- to posttreatment regardless of treatment condition or response.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that child-focused anxiety treatments, regardless of intervention condition, can result in improvements in nontargeted parent symptoms and family functioning particularly when children respond successfully to the treatment.

Keywords: child anxiety, family outcomes, parent anxiety, family functioning, treatment, parent psychopathology, randomized controlled trial, pharmacotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy

Introduction

Effective treatments for pediatric anxiety disorders target factors that are implicated in the development and maintenance of symptoms, such as neurobiological (e.g., serotonin disturbance), cognitive (e.g., distortions, bias toward threat), behavioral (e.g., avoidance), or environmental/familial vulnerabilities (e.g., modeling of anxiety, autonomy-limiting parenting behaviors).1–6 The latter factor—environmental and familial vulnerabilities—acknowledges high rates of concordance for anxiety disorders among first-degree relatives. Children of anxious parents are significantly more likely to have an anxiety disorder compared to children of nonanxious parents.7–9 Indeed, there is a substantial literature indicating that parental psychopathology, and anxiety in particular, is associated with higher levels of child anxiety, predicts poor treatment outcomes (in some studies), and may play a role in the maintenance of anxiety disorders.10–16 Evidence is also clear that specific parenting behaviors (e.g., excessive accommodation and overcontrol) are associated with higher anxiety in youth.17–20 The direction of effects has been found to be reciprocal.17 Consequently, treatment research on environmental vulnerabilities has focused on modifying specific parenting behaviors associated with child anxiety.10–16

Additional family variables, such as low levels of general family functioning and cohesion, and high levels of dysfunction and conflict, are also associated with greater child anxiety and unfavorable acute treatment outcomes.14,21–25 Empirical findings that environmental/familial factors and child anxiety are reciprocal (children and parents, e.g., influence one another's level of anxiety) may explain the associations among parental psychopathology, family distress, and child anxiety identified in the above studies.17,26 Thus, a child's anxiety requiring family accommodation could result in family conflict just as family conflict could increase a child's anxiety. Consistent with developmental models of anxiety27,28 effective treatment of the child may resolve parental or family distress, yet the current treatment literature provides little information about the effects of child treatment on parent and family variables. Parent and family “spillover effects”5 have been evaluated in some cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) trials21,26,29–31 but not in pharmacological trials or combined treatment trials. In three of the four CBT trials, positive effects were identified on parent-reported family dysfunction, parental frustration with the child, parental anxiety symptoms and general psychopathology,21,26,30 and remission of maternal anxiety diagnosis29 even though these variables were not targeted in the treatment.

This study examined data from the largest comparative treatment trial for pediatric anxiety disorders, which offered a unique opportunity to examine parent and family outcomes as a function of both treatment condition, including CBT and medication, and child treatment response. The Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Treatment Study (CAMS) enrolled 488 youth and compared the relative efficacy of sertraline (SRT), CBT, combination SRT + CBT treatment (COMB), and pill placebo (PBO) for pediatric anxiety disorders, and found that all active treatments outperformed PBO and that COMB offered the highest chances of significant symptom reduction and diagnostic recovery.32,33 Using these data, the current study extends existing research on whether varied child-focused anxiety treatments benefit parents and families; specifically, the effects of child-focused treatment on parent psychological distress, parent anxiety symptoms, global family functioning, and family burden associated with a psychologically ill child were examined. Based on previous empirical data, we hypothesized that parent and family outcomes would be significantly more improved in families of youth who successfully responded to treatment compared to those who did not respond. As COMB was most effective of the active treatments, it was hypothesized that parent and family outcomes would be superior among responders to the COMB treatment condition relative to responders in the other treatment conditions. Identification of familial benefits associated with child treatment is important for appreciating the full value of pediatric anxiety interventions.

Materials and Methods

Participants

As stated, participants were part of a large randomized controlled trial, CAMS, for pediatric anxiety disorders.33 CAMS was conducted across six medical and academic institutions in the United States and enrolled 488 children and adolescents (ages 7–17) who met principal DSM-IV-TR34 criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and/or separation anxiety disorder, and their parents. Mean age was 10.69 years (SD = 2.80), and 74.2% were 7–12 years old; 49.6% of the participants were female, and 78.9% were Caucasian. The majority of participants (74.5%) were of middle to high socioeconomic status, as indicated by a score of 40–66 on the Hollingshead four-factor index of social status.35

Procedures

Study procedures were approved by each site's Institutional Review Board. Prior to completing study procedures, participants signed informed consent. Diagnostic eligibility was determined using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children and Parents (ADIS-C/P),36,37 and participants completed a battery of questionnaires before they were randomly assigned to 12 consecutive weeks of child-focused treatment in one of the four conditions. At posttreatment, the diagnostic evaluation was repeated by a blind/independent evaluator (IE) and children and their parents repeated the questionnaire battery. Detailed demographic data, diagnostic characteristics, and methodology are described elsewhere.33,38,39

CAMS Treatments

Pharmacotherapy

The medication condition was double-blinded, and SRT or matching PBO was dispensed by an investigational pharmacist. Treatment included eight conjoint clinic visits and four telephone visits during the 12-week acute phase. Appointments lasted approximately 30–60 min and were devoted to a review of the participant's symptomatology, overall functioning and impairment, response to treatment, and presence of side effects/adverse events, all in a context of supportive care. Medication was dosed on a “fixed-flexible” titration schedule corresponding to clinician-assigned symptom severity and ascertainment of clinically significant side effects. Dosing started at 25 mg per day and was gradually increased up to 200 mg per day by week 8.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

The CAMS CBT protocol utilized the Coping Cat manual for children and the developmental modification, the CAT Project, for adolescents.40, 41 Treatment duration was 12 weeks, and involved 12 60-min weekly individual child-focused sessions and 2 parent sessions scheduled immediately after the child sessions at weeks 3 and 5. The first six CBT sessions focused on teaching new skills to the child (e.g., the FEAR plan that included relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, and developing a hierarchy of anxiety-provoking situations), whereas the second six sessions provided the child opportunities to practice newly learned anxiety management skills and engage in gradual exposure to anxiety-provoking situations within and outside of the sessions. During the parent sessions, information was provided about the treatment model, and strategies for parents to support the child's treatment were collaboratively identified. The focus of these parent sessions was on psychoeducation and supporting the child; neither parental anxiety symptoms nor specific parenting behaviors were directly targeted.

Combination Treatment

Participants in the combination treatment condition (COMB) received all the components from the medication-only and CBT-only treatment conditions, with the exception that the participant, parent(s), and clinician were aware that the participant was receiving active SRT. Medication and CBT visits generally occurred on the same day starting with pharmacotherapy.

Measures

Independent/Predictor Variables

Child Treatment Response

Global improvement of child anxiety symptoms and impairment was rated by an IE at 12 weeks posttreatment using the seven-item Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) Scale.42 Scores range from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse), and children were categorized as treatment responders if the CGI-I score was 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), or as treatment nonresponders if the CGI-I score was ≥3. The CGI-I is a widely used measure of outcomes, especially in psychopharmacological pediatric clinical trials. The CGI-I is strongly related to self-report and clinician-administered measures of symptomatology and functional impairment.43

Child Treatment Condition

Children were randomly assigned to 12 consecutive weeks of treatment with CBT (n = 139), SRT (n = 133), COMB (n = 140), or PBO (n = 76). The medication-only conditions were double-blinded.

Covariates

The following variables were included as covariates to control for their potential effects on the dependent variables: child's age, gender, minority status, socioeconomic status (SES), treatment site, pretreatment depressive symptoms assessed by child self-report on the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire,44 and pretreatment clinical severity assessed by an IE using the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S) Scale.42

Dependent/Outcome Variables

Parental Psychological Distress (Parent Report)

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)45 is a 53-item self-report measure of psychopathology. For the present analyses, the Global Severity Index (BSI–GSI) provided a single composite score of current symptoms of somatization, obsessive–compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychosis. Higher scores suggest greater severity of psychological distress. Internal consistency was .95 at pre- and posttreatment assessments.

Parental Anxiety (Parent Report)

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-A-Trait Scale (STAI-A-Trait)46 is a self-report questionnaire for measuring symptoms of long-standing “trait anxiety” in adults. Total scores range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. Consistent with prior studies,47,48 internal consistency was excellent, with Cronbach's alphas of .90 at pretreatment and .91 at posttreatment.

Family Dysfunction (Child and Parent Report)

The Brief Family Assessment Measure-III (BFAM-III)49 is a14-item questionnaire that assesses perceptions of family functioning during the last 2 weeks. Items such as “We take the time to listen to each other” and “When things aren't going well it takes too long to work them out” are scored on a 5-point scale. Items are summed to create a total score that is converted into a T score. Higher scores reflect greater levels of perceived family dysfunction. Cronbach's alpha ranged between .76 and .87 for children and parents across pre- and posttreatment assessments.

Family Burden (Parent Report)

The 21-item Burden Assessment Scale (BAS)50 measures objective and subjective caregiver burden associated with having a child with a mental health disorder. Parents indicated the degree to which the child's anxiety disrupts family life and routines on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). A higher score signifies greater burden. Consistent with high internal consistency in initial studies, Cronbach's alpha for the current sample was .91 at pretreatment and .93 at posttreatment.

Statistical Analyses

Missing data were handled using a sequential regression multivariate imputation51,52 algorithm in the SAS IVEware package,53 assuming missingness at random. Twenty (20) imputed data sets were generated, and then results of identical analyses on each imputed data set were combined using Rubin's established guidelines.51

Preliminary analyses included one-way analyses of variance tests to compare pretreatment means on the dependent variables based on treatment condition and treatment response status. Next, five univariate one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models using SPSS version 19 General Linear Modeling were fitted to determine predicted mean (e.g., expected) values of parental anxiety, parental psychological distress, family dysfunction (child and parent report), and parent perceptions of family burden at posttreatment (week 12), and to test hypotheses of between group differences at week 12. In addition to seven grand-mean centered covariates (i.e., age, gender, race, SES, site, depression, clinical severity), each model included pretreatment scores for the dependent variables, two predictor variables (treatment condition, treatment response), and a treatment condition × treatment response interaction term. Because none of the covariates yielded significant main effects, they were removed from the reported analyses.

Results

Pre- and posttreatment means and standard deviations on parent and family functioning variables by treatment condition and treatment response are presented in Tables 1 and 2. There were no significant between-group differences on pretreatment parent and family functioning for treatment conditions (F(3, 484) = 1.194–3.465, P > .05) or treatment response groups (F(1, 486) = 0.161–2.029, P > .05). Preliminary analyses evaluating the homogeneity-of-regression assumption indicated that the relationships between the covariates and the dependent variables did not differ significantly as a function of the independent variables. With one exception described below, examination of the Levene's F statistic for each one-way ANCOVA confirmed that the underlying assumption of homogeneity of variance was met.

Table 1. Pre- and posttreatment parent and family variables by treatment condition (N = 488).

| COMB M (SD) |

SRT M (SD) |

CBT M (SD) |

PBO M (SD) |

Group comparisons | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Pre-treatmenta | Post-treatmentb | Pre-treatmentc | Post-treatmentd | Pre-treatmente | Post-treatmentf | Pre-treatmentg | Post-treatmenth | ||

| Parent outcomes | |||||||||

| BSI | 0.52 (0.42) | 0.26 (0.30) | 0.40 (0.37) | 0.33 (0.41) | 0.50 (0.43) | 0.35 (0.35) | 0.49 (0.48) | 0.41 (0.43) | b,d,f,h < a,c,e,g |

| STAIT | 39.31 (10.03) | 34.30 (9.12) | 37.64 (8.50) | 34.88 (9.02) | 39.62 (9.41) | 36.41 (9.31) | 37.60 (10.24) | 36.58 (9.67) | |

| Family outcomes | |||||||||

| BFAM—parent | 48.11 (11.38) | 43.27 (12.68) | 43.95 (10.66) | 42.88 (10.07) | 46.49 (10.45) | 45.83 (10.50) | 45.89 (10.28) | 43.02 (9.72) | |

| BFAM—child | 49.44 (8.52) | 45.62 (9.10) | 47.32 (8.80) | 45.06 (9.22) | 47.70 (8.46) | 47.18 (9.50) | 48.63 (8.44) | 48.11 (8.85) | |

| BAS | 47.03 (13.43) | 38.04 (12.12) | 46.80 (12.89) | 38.13 (12.12) | 47.04 (13.56) | 37.75 (12.28) | 46.25 (13.17) | 37.08 (12.12) | |

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory—higher scores, greater severity of psychological distress; STAIT, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-A-Trait Scale— higher scores, higher levels of anxiety; BFAM, Brief Family Assessment Measure—higher scores, greater levels of perceived family dysfunction; BAS, Burden Assessment Scale—higher scores, greater perceived burden.

Table 2. Pre- and posttreatment parent and family variables by treatment response (N = 488).

| Responder M (SD) |

Nonresponder M (SD) |

Full Sample M (SD) |

Group comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Pretreatmenta | Posttreatmentb | Pretreatmentc | Posttreatmentd | Pretreatmente | Posttreatmentf | ||

| Parent outcomes | |||||||

| BSI | 0.47 (0.40) | 0.26 (0.29) | 0.50 (0.46) | 0.45 (0.46) | 0.48 (0.42) | 0.33 (0.37) | b < a,c,d f < e |

| STAIT | 39.02 (9.43) | 34.55 (9.04) | 38.06 (9.64) | 37.05 (9.46) | 38.68 (9.51) | 35.44 (9.26) | b < a,c,d f < e |

| Family outcomes | |||||||

| BFAM—parent | 46.63 (10.88) | 43.13 (10.89) | 45.35 (10.74) | 45.16 (11.08) | 46.17 (10.84) | 43.86 (10.99) | b < a,c,d f < e |

| FAM—child | 48.15 (8.37) | 45.60 (8.73) | 48.39 (8.98) | 47.56 (10.02) | 48.24 (8.58) | 46.30 (9.25) | f < e |

| BAS | 46.98 (13.40) | 37.98 (12.10) | 46.62 (13.08) | 37.57 (12.31) | 46.85 (13.31) | 37.83 (12.19) | f < e |

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory—higher scores, greater severity of psychological distress; STAIT, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-A-Trait Scale— higher scores, higher levels of anxiety; BFAM, Brief Family Assessment Measure—higher scores, greater levels of perceived family dysfunction; BAS, Burden Assessment Scale—higher scores, greater perceived burden.

In each of the five ANCOVAs (Table 3), the interaction of treatment condition × treatment response was not significant so the main effects were interpreted. The main effect for treatment condition was not significant in any model. The main effect for treatment response was not significant when family burden and child-reported family dysfunction were entered as outcome variables. Follow-up independent samples t-tests, however, revealed significant reductions from pre- to posttreatment on both family burden (t(487) = 14.64, P < .001) and child-reported family dysfunction (t(487) = 4.50, P < .001).

Table 3. Analysis of covariance for parent and family outcomes (N = 488).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSI—parent | STAIT—parent | BFAM—parent | BFAM—child | BAS—parent | |

| Posttreatment parent and family outcomes | |||||

| Pretreatment score | 90.18** | 277.83** | 223.68** | 113.86** | 166.99** |

| Treatment condition | 1.38 | 0.94 | 2.30 | 2.34 | 1.34 |

| Treatment response | 18.30** | 12.19** | 9.52* | 2.83 | 1.46 |

| Treatment condition × treatment response | 1.29 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 1.90 | 0.79 |

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; STAIT, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-A-Trait Scale; BFAM, Brief Family Assessment Measure; BAS, Burden Assessment Scale.

P < .01;

P < .001.

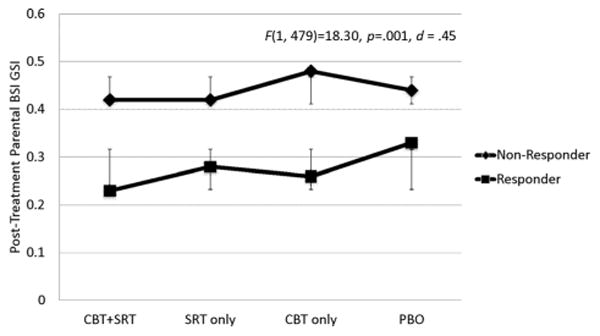

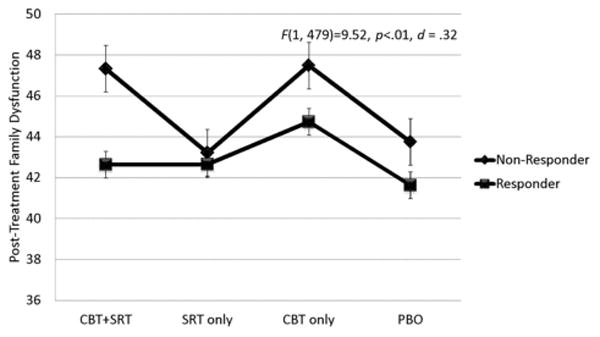

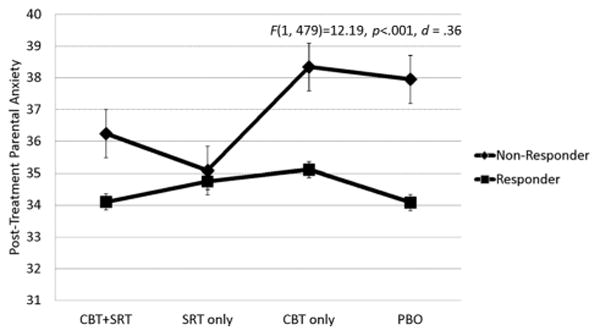

The main effect for treatment response was significant for both parent outcomes and parent-reported family functioning. Specifically, posttreatment global psychological distress, trait anxiety, and parent-reported family dysfunction were significantly lower among parents of children rated as responders compared to nonresponders (Figs. 1–3). When parental psychological distress was entered as the dependent variable, the assumption of equality of variance was not met (F(7, 480) = 6.353, P < .001) suggesting that results for this model should be interpreted with caution. Parents of responders reported an average improvement of 0.21 on global psychological severity which was significantly greater than the average improvement of 0.05 reported by parents of nonresponders (F(1, 479) = 18.30, P = .001). With regard to parental anxiety, parents of responders reported an average improvement of 4.47 on the total score, and this was significantly greater compared to an improvement of 1.01 for parents of nonresponders (F(1, 479) =12.19, P< .001). Finally, parents of treatment responders reported an average improvement of 3.50 on the family functioning scale whereas parents of nonresponders reported an average improvement of 0.19. The Cohen's d effect sizes for the significant adjusted mean differences at posttreatment were 0.45 for psychological distress, 0.36 for parent anxiety, and 0.32 for family dysfunction.

Figure 1.

Estimated marginal means of parental psychopathology by child treatment response and condition.

Figure 3.

Estimated marginal means of parent-reported family dysfunction by child treatment response and condition.

In a post hoc exploratory step, we considered that the CBT conditions could offer relatively more benefits to parents due to the increased time spent with a clinician or the potential for parents to learn and use coping skills taught to the children. Thus, treatment groups involving CBT were collapsed and compared to medication groups, but this analysis did not result in a significant effect of treatment condition on parent and family outcomes.

Discussion

This study examined the “spillover effects”5 of child-focused treatment on parental and family outcomes that were not targeted in treatment. Findings supported a small body of literature indicating that child-focused treatment does confer benefits to parents' mental health functioning and the family at large.21,26,29 However, findings extended existing research by showing that improvements in parent-reported psychological distress, anxiety, and family functioning corresponded to successful treatment for the child, and were not afforded to all families. That parent and family factors were not specifically targeted in CAMS treatment supports the notion of bidirectional or reciprocal relationships between environmental risk factors and child anxiety symptoms.26 While directionality cannot be pinpointed in the present study and may be challenging to tease apart methodologically, parents who personally benefitted the most had children who benefitted the most from treatment. Thus, parental anxiety and general psychological distress may be reactive or increased by a child's anxiety disorder, a conclusion that is supported by previous studies.17,26

On the other hand, family burden and child-reported family dysfunction improved overall regardless of the child's treatment response. Perceptions of high family burden may be relieved merely by initiating treatment, having expectations for symptom relief, and/or gaining increased insight regarding the nature of anxiety disorders. Similarly, children may report improved family functioning since treatment involves devoted time toward addressing their anxiety disorder(s). Regardless of the explanation, findings of an overall reduction in family burden and improvement in family functioning, independent of treatment efficacy, highlights that there are meaningful potential gains for treatment-seeking families apart from the potential to achieve targeted symptom reduction.

This study was also the first to examine whether secondary benefits to the family are dependent upon the treatment condition, namely SRT-only, Coping Cat CBT-only, SRT plus CBT (COMB), and pill placebo, but the hypothesis that superior gains for the family would be achieved in the COMB condition was not supported. In an exploratory step, we considered whether families might benefit more in the CBT conditions in which two sessions were devoted to parents. In these parent sessions, they received information about specific approaches used in the treatment of the child, were encouraged to share their impressions of their child, and were asked to facilitate their children in practicing coping skills and completing exposure tasks. It should be noted that, recently, there is now a parent booklet (The Coping Cat: Parent Companion) that provides a description of the child's treatment and ways parents can assist.54 However, in the present study, results for parent and family outcomes were not significantly different when treatment conditions involving CBT (CBT-only, COMB) were combined and compared to medication-only conditions. The absence of an effect for treatment condition suggests that parent improvement is linked to child improvement and supports the notion that child anxiety shapes the family environment. This finding highlights the fact that any treatment leading to improvement in child anxiety will likely confer benefits for parents and families.

Findings from this study extend the implications of successful youth-focused anxiety treatments. First, that nontargeted family factors improved during the course of effective child treatments strengthens the value of pediatric anxiety intervention from a public health perspective. Second, the improvement of parent and family factors during the course of treatment may benefit children over the long term. Specifically, continued progress or maintenance of children's gains could be engendered by interrupting the cycle in which child anxiety and maladaptive parent and family variables influence each other. Indeed, existing research suggests that the absence of parental anxiety is associated with maintenance of treatment gains in youth.29 Additional research that identifies predictors of long-term child functioning following completion of anxiety treatment is needed.

Limitations Merit Consideration

Unlike youth diagnostic status, clinical severity, and treatment response, which were determined by a blinded evaluator, all parent and family variables were based on self-report, which may affect the internal validity of outcome data (e.g., response shift).55 Additionally, there are variables of interest, such as family conflict and cohesion, which were not captured in the rating scales used in this study. Thus, the demonstrated improvements in family functioning are unclear with regard to specific characteristics or processes in the family that benefit from child-focused treatment. Another design issue that should be noted is the unbalanced randomization scheme, which resulted in a smaller size placebo group compared to active treatment groups. Although the cell sizes were adequately powered to address acute treatment effects on symptom improvement, it is possible that the lack of a treatment-type effect in the current investigation is explained by the relatively smaller size of the placebo group. Finally, the sample was predominantly Caucasian and of middle to high socioeconomic status, which limits the generalizability of findings to other racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

In sum, the current study shows that psychosocial and medication treatments for pediatric anxiety disorders lead to reductions in parent anxiety symptoms and global psychological distress as well as family dysfunction and burden associated with having a psychologically ill child, and that some benefit to the family is achieved even in the absence of significant improvement in targeted youth anxiety symptoms.

Figure 2.

Estimated marginal means of parental anxiety by child treatment response and condition.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants (U01 MH064089 to Dr. Walkup; U01 MH064092 to Dr. Albano; U01 MH064003 to Dr. Birmaher; U01 MH063747 to Dr. Kendall; U01 MH064107 to Dr. March; U01 MH064088 to Dr. Piacentini) from the National Institute of Mental Health. Sertraline and matching placebo were supplied free of charge by Pfizer. Views expressed within this article represent those of the authors and are not intended to represent the position of NIMH, NIH, or DHHS.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors receive salaries from their institutions. In addition, in the past 3 years, Dr. Albano has received grant funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), served as a consultant for Bracket Global, received an author's fee from Lynn Sonberg books and royalties from Oxford University Press, and has pending grant support from the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Dr. Birmaher has received NIMH grant funding, book royalties from Random House, Inc. and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, and has NIMH pending grant support. Dr. Drake has received NIMH and Institute of Educational Sciences (IES) grant support. Dr. Keeton has current and pending grant support from NIMH and IES. Dr. Ginsburg has received grant funding and has funding pending from NIMH and IES. Dr. Kendall has received NIMH grant support and funding for travel and presentations, and royalties for the sale of books and anxiety treatment materials. Dr. March has received NIMH grant support, travel funding from Duke University Medical Center, and has served as a board member for Pfizer, Inc. and Eli Lilly, and received royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (measure was donated at no cost to the current study). Dr. Piacentini has received NIMH grant support, royalties from Oxford University Press and Guilford, and speaking honoraria and travel funds from the International Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Foundation and the Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA). Dr. Rynn has received NIMH grant support and royalties from APPI Press, served as a consultant for Shire, and has pending grants from Shire, NIMH, NICHD, Pfizer, Inc., Eli Lilly, and Merck. Dr. Sakolsky has received NIMH grant funding, served on the editorial board of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmcology News, has pending grant funding from NARSAD, received funding from the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry for 2012 review course development, and travel support from American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology for a conference. Dr. Walkup has received NIMH grant support, royalties from Oxford University Press and Guilford, travel funds from TSA, medication and matching pill placebo for the current study from Pfizer, Inc., has pending grant funding from TSA, and has served as a board member of TSA; Anxiety Disorders Association of America; Trichotillomania Learning Center, and as a consultant for Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; Contract grant numbers: U01 MH064089, U01 MH064092, U01 MH064003, U01 MH063747, U01 MH064107, U01 MH064088.

References

- 1.Bar-Haim Y, Morag I, Glickman S. Training anxious children to disengage attention from threat: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:861–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake KL, Ginsburg GS. Family factors in the development, treatment, and prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15:144–162. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisak BJ, Grills-Taquechel A. Parental modeling, reinforcement, and information transfer: risk factors in the development of child anxiety? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2007;10:213–231. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson JL, Rapee RM. Familial and social environments in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders. In: Antony MM, Stein MB, editors. Oxford Handbook of Anxiety and Related Disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall PC. Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures. 4th. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strawn JR, Wehry AM, DelBello MP, Rynn MA, Strakowski S. Establishing the neurobiologic basis of treatment in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:328–339. doi: 10.1002/da.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Micco JA, Henin A, Mick E, et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring at high risk for anxiety: a meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieb R, Wittchen H, Höfler M, Fuetsch M, Stein MB, Merikangas KR. Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:859–866. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner SM, Beidel DC, Costello A. Psychopathology in the offspring of anxiety disorders patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:229–235. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodden DHM, Bögels SM, Nauta MH, et al. Child versus family cognitive-behavioral therapy in clinically anxious youth: an efficacy and partial effectiveness study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1384–1394. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318189148e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobham VE, Dadds MR, Spence SH. The role of parental anxiety in the treatment of childhood anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:893–905. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginsburg GS, Becker KD, Drazdowski TK, Tein J. Treating anxiety disorders in inner city schools: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial comparing CBT and usual care. Child Youth Care Forum. 2012;41:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10566-011-9156-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginsburg GS, Silverman WK, Kurtines WK. Family involvement in treating children with phobic and anxiety disorders: a look ahead. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:457–473. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liber JM, van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, et al. Parenting and parental anxiety and depression as predictors of treatment outcome for childhood anxiety disorders: has the role of fathers been underestimated? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:747–758. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapee RM. Group treatment of children with anxiety disorders: outcome and predictors of treatment response. Aust J Psychol. 2000;52:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC, Weersing VR. Examining outcome variability: correlates of treatment response in a child and adolescent anxiety clinic. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:422–436. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson JL, Doyle AM, Gar N. Child and maternal influence on parenting behavior in clinically anxious children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:256–262. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rork KE, Morris TL. Influence of parenting factors on childhood social anxiety: direct observation of parental warmth and control. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2009;31:220–235. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, Hwang W, Chu BC. Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:134–151. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford AM, Manassis K. Familial predictors of treatment outcome in childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1182–1189. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginsburg GS, Siqueland L, Masia-Warner C, Hedtke KA. Anxiety disorders in children: family matters. Cogn Behav Prac. 2004;11:28–43. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes AA, Hedtke KA, Kendall PC. Family functioning in families of children with anxiety disorders. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22:325–328. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey Y, Marin CE, Silverman WK. Failures in cognitive-behavior therapy for children. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:1140–1150. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Victor AM, Bernat DH, Bernstein GA, Layne AE. Effects of parent and family characteristics on treatment outcome of anxious children. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman WK, Kurtines WM, Jaccard J, Pina AA. Directionality of change in youth anxiety treatment involving parents: an initial examination. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:474–485. doi: 10.1037/a0015761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ginsburg GS, Schlossberg MC. Family-based treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rapee RM. Family factors in the development and management of anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Settipani CA, O'Neil KA, Podell JL, Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Youth anxiety and parent factors over time: directionality of change among youth treated for anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 42:9–21. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.719459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waters AM, Ford LA, Wharton TA, Cobham VE. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for young children with anxiety disorders: comparison of a child + parent condition versus a parent only condition. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsburg GS, Kendall PC, Sakolsky D, et al. Remission after acute treatment in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: findings from the CAMS. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:806–813. doi: 10.1037/a0025933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollingshead AB. Commentary on “the indiscriminate state of social class measurement. Soc Forces. 1971;49:563–567. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albano AM, Silverman WK. Clinician's Guide to the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Versions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverman WK, Albano AM. The anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV, research and lifetime version for children and parents (ADIS-RLV) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; [Google Scholar]

- 38.Compton SN, Walkup JT, Albano AM, et al. Child/adolescent anxiety multimodal study (CAMS): rationale, design, and methods. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2010;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendall PC, Compton SN, Walkup JT, et al. Clinical characteristics of anxiety disordered youth. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendall PC, Hedtke KA. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual. 3rd. Workbook Publishing; Ardmore, PA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kendall PC, Choudhury M, Hudson J, Webb A. "The C.A.T. Project” Manual for the Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Anxious Adolescents. Workbook Publishing; Ardmore, PA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy W The clinical global impression scale. The ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised (DHEW Publ. No. ADM 76-338) Rockville, MD: U.S. Departmentof Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research; 1976. pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Evaluation of the clinical global impression scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychol Med. 2003;33:611–622. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angold A, Costello E. Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) Durham, NC: Developmental Epidemiology Program, Duke University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grös DF, Antony MM, Simms LJ, McCabe RE. Psychometric properties of the state-trait inventory for cognitive and somatic anxiety (STICSA): comparison to the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) Psychol Assess. 2007;19:369–381. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grös DF, Simms LJ, Antony MM. Psychometric properties of the state-trait inventory for cognitive and somatic anxiety (STICSA) in friendship dyads. Behav Ther. 2010;41:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skinner HA, Steinhauer P, Santa-Barbara J. Brief Family Assessment Measure (FAM) Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinhard SC, Gubman GD, Horwitz AV, Minsky S. Burden Assessment Scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17:261–269. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, Van Hoewyk J. IVEware: imputation and variance estimation software. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kendall PC, Podell J, Gosch E. The Coping Cat: Parent Companion. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brossart DF, Clay DL, Willson VL. Methodological and statistical considerations for threats to internal validity in pediatric outcome data: response shift in self-report outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:97–107. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]