Abstract

Objective

To determine if adequate versus excessive gestational weight gain (GWG) attenuated the association between maternal obesity and offspring outcomes.

Study design

Data from 313 mother-child pairs participating in the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes in Children (EPOCH) study were used to test this hypothesis. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and weight measures throughout pregnancy were abstracted from electronic medical records. GWG was categorized according to the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) criteria as adequate or excessive. Offspring outcomes were obtained at a research visit (average age 10.4 years) and included body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), subcutaneous (SAT) and visceral adipose tissue (VAT), HDL-cholesterol (HDL-c) and triglyceride (TG) levels.

Results

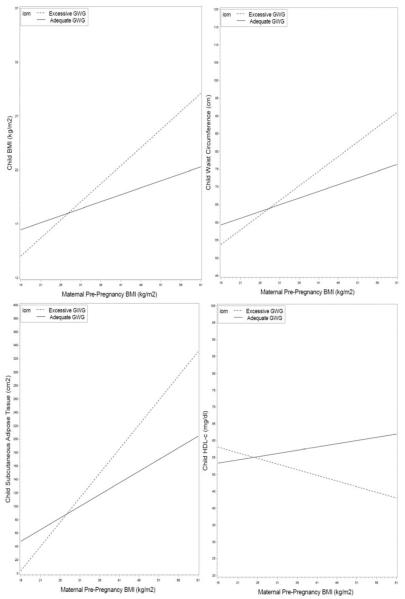

More overweight/obese mothers exceeded the IOM GWG recommendations (68%) compared with normal weight women (50%) (p<0.01). Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with worse childhood outcomes, particularly among offspring of mothers with excessive GWG [increased BMI (20.34 vs 17.80 kg/m2, WC (69.23 vs 62.83 cm), SAT (149.30 vs 90.47 cm2), VAT (24.11 vs 17.55 cm2), and HOMA-IR (52.52 vs 36.69), all p< 0.001]. The effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on several childhood outcomes was attenuated for offspring of mothers with adequate vs excessive GWG (p<0.05 for the interaction between maternal BMI and GWG status on childhood BMI, WC, SAT, and HDL-c).

Conclusion

Our findings lend support for pregnancy interventions aiming at controlling GWG to prevent childhood obesity.

Keywords: maternal obesity, childhood obesity, gestational weight gain, offspring adiposity

The prevalence of obesity has been increasing dramatically in the United States (U.S.), including among women of reproductive age.1 Maternal obesity is a major risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM) and future type 2 diabetes (T2D).2 Moreover, observational studies suggest an independent association of maternal obesity with excessive fetal growth3, 4 and childhood obesity.5 Alarmingly, increasing obesity trends are now observed early in life, even among young infants6, pointing toward harmful changes in the environment in which contemporary children are born and raised.7 These and other observations lead to the hypothesis that maternal obesity during pregnancy is associated with lifelong consequences in the offspring 8 and, possibly, over successive generations.9 It has been suggested that a trans-generational “vicious cycle” results, explaining at least in part the increases in obesity, GDM and T2D seen over the past several decades.10 In addition, obese children tend to become obese adults and, once present, obesity and its consequences are expensive and difficult to treat. This makes pregnancy a crucial window of opportunity for obesity prevention in this and the next generation.

The role of gestational weight gain (GWG) on childhood adiposity outcomes is less clear and incompletely studied. Some, but not all11, 12, epidemiologic studies have found that higher GWG is associated with higher body mass index (BMI) in childhood13–17 and adolescence5 and with increased fat mass and poorer metabolic and vascular traits at age 9 years.18 Some studies have suggested that the association of higher maternal weight gain and offspring obesity persists into adulthood.12 Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and excessive GWG have independently been linked to increased adiposity in the offspring.11, 16, 17, 19–21 In a group of preschool children, the odds of being categorized as overweight by age 4–5 years was increased by 57% in children exposed to both a maternal pre-pregnancy BMI above ≥25 kg/m2 and excessive weight gain during pregnancy.16 It remains unclear however, if the effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on childhood adiposity outcomes is mitigated by adequate weight gain during pregnancy.

The answer to this question is important as it would provide support to the notion that healthier weight gain patterns during pregnancy may improve the short and long-term effects on offspring who have been exposed to maternal obesity. To address this question using data from the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes among Children (EPOCH) study in Colorado.

Methods

The EPOCH study is an observational historical prospective cohort comprised of children born between 1992 and 2002 at a single hospital in Colorado, whose biological mothers were members of the Kaiser Permanente of Colorado Health Plan (KPCO) and who were offspring of singleton pregnancies. All children exposed to maternal gestational diabetes (GDM) were eligible, together with and a random sample of children not exposed to GDM. Children were invited to attend an in person-research visit when they were on average 10.5 years (range 6–13 years) and approximately 68% agreed to participate.

Included in this analysis are 313 mother-child pairs (141 non-Hispanic white, 145 Hispanic, 27 non-Hispanic black) who were part of the EPOCH study and had complete data on maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, GWG and offspring adiposity outcomes. Children and their mothers completed a research visit between January 2006 and October 2009. Because the EPOCH study was specifically designed to explore the long-term effects of maternal GDM on offspring, the cohort is enriched in offspring of GDM mothers. As we were exploring specific hypotheses regarding the role of excessive GWG as effect modifier, the small number of offspring of mothers who gained insufficient gestational weight during pregnancy were excluded. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent and youth provided written assent.

Maternal Measures

Maternal pregnancy measures (weight, GDM) and offspring birth weight were obtained from the KPCO perinatal database, a linkage of the maternal and perinatal medical record containing prenatal and delivery events for each woman. Maternal pre-pregnancy weight was measured before the last menstrual cycle preceding pregnancy. Maternal height was collected at the in-person research visit and used to calculate pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2). BMI was categorized as normal weight (18.5– 25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (≥ 25kg/m2). Multiple weight measures during pregnancy (on average 4 per participant) were used to model GWG using a longitudinal mixed effects model which included fixed effects for time, time squared, pre-pregnant BMI, maternal age, gravidity, and a time by pre-pregnant BMI interaction. The model included subject specific intercept and slope terms. GWG was estimated using the absolute predicted weight gain for a full term pregnancy (model predicted weight at term minus model predicted weight at conception). Women were categorized as either exceeding or meeting the 2009 recommended Institute of Medicine (IOM) GWG guidelines (adequate total GWG for normal BMI pre-pregnancy 11.4–15.9kg and overweight/obese BMI pre-pregnancy 5–11.4 kg).22 Women who gained inadequate weight during pregnancy were excluded from this analysis, according to our a priori hypothesis.

Physician-diagnosed GDM was coded as present if diagnosed through the standard KPCO screening protocol and absent if screening was negative. Since the 1990s, KPCO has routinely screened for GDM in all non-diabetic pregnancies using a two-step standard protocol and criteria based on the National Diabetes Data Group recommendations.23

Childhood measures

All children were invited to an in-person research visit, which included anthropometric measures, questionnaires, a magnetic resonance imaging exam (MRI) of the abdominal region and a fasting blood sample. Race/ethnicity was self-reported using 2000 U.S. census-based questions and categorized as Hispanic (any race), non-Hispanic white, or non-Hispanic African American. Pubertal development was assessed by child self-report with a diagrammatic representation of Tanner staging adapted from Marshall and Tanner.24 Youth were categorized as Tanner < 2 (prepubertal) and ≥2 (pubertal). Total energy intake (kilocalories per day) was assessed using the Block Kid's Food Questionnaire. 25 Self-reported key activities, both sedentary and non-sedentary, performed during the previous 3 days was measured using a 3-day Physical Activity Recall (3DPAR) questionnaire.26 Each 30-minute block of activity was assigned a metabolic equivalent variable to accommodate the energy expenditure. Results were reported as the average number of 30-minute blocks of moderate-to-vigorous activity per day. Current height and weight were measured in light clothing and without shoes. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1kg using a portable electronic SECA scale. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1cm using a portable SECA stadiometer. Height and weight were measured and recorded twice, and an average was taken. Scales and stadiometers were calibrated every 2 months using standard weights for scales and an aluminum measuring rod for the stadiometer. BMI was calculated as kg/m2. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 1 mm at the midpoint between the lower ribs and the pelvic bone with a metal or fiberglass non-spring loaded tape measure. MRI of the abdominal region was used to quantify visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) with a 3T HDx imager (General Electric, Waukashau, WI) by a trained technician. Each participant was placed supine and a series of T1-weighted coronal images were taken to locate the L4/L5 plane. One axial, 10-mm, T1-weighted images at the umbilicus or L4/L5 vertebra was analyzed to determine SAT and VAT content. The analysis technique used was a modification of the technique of Engelson,27 where adipose tissue regions were differentiated by their signal intensity and location. Images were analyzed by a single reader.

Cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) were obtained while the patient was fasting and measured using the Olympus (Center Valley PA) AU400 advanced chemistry analyzer system. Estimated insulin resistance was based on the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA-IR), calculated using fasting glucose and insulin levels collected at the study visit according to the formula: [fasting glucose (mmol/L) × fasting insulin (μU/ml)/ 22.5].

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Pre-pregnant BMI was categorized as normal weight (18.5– 25 kg/m2) and overweight/obese (≥ 25kg/m2). Descriptive analyses compared pre-pregnant BMI groups using both t-tests and χ2 tests (Table I). Univariate regression was used to examine whether maternal pre-pregnant BMI was associated with childhood adiposity-related variables (including BMI, waist circumference, SAT and VAT, HDL-c, triglycerides and HOMA-IR). An ANOVA model was used to investigate the modifying effect of GWG on the relationship between pre-pregnancy maternal BMI and childhood adiposity-related variables. All models were controlled for potential confounders which included current offspring age, sex, race/ethnicity, Tanner stage, birth weight and maternal GDM status.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population (mean±SD) according to maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity status.

| Normal Weight (n=149) | Overweight or Obese (n=164) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Characteristics | |||

| Maternal age at delivery (yrs) | 30.38±5.73 | 30.66±5.84 | 0.67 |

| Nulliparous, N (% yes) | 42 (28.19) | 50 (30.49) | 0.66 |

| Pre-Pregnant BMI (kg/m2) | 21.70±1.99 | 30.76±5.29 | <0.0001 |

| GDM, N (%) | 24 (16.11) | 39 (23.78) | 0.09 |

| 1st trimester weight gain (kg) | 3.98±1.07 | 3.18±1.51 | <0.0001 |

| 2nd trimester weight gain (kg) | 4.88±1.08 | 4.08±1.53 | <0.0001 |

| 3rd trimester weight gain (kg) | 5.68±1.07 | 4.89±1.51 | <0.0001 |

| Total gestational weight gain (kg) | 16.52±3.55 | 13.58±5.41 | <0.0001 |

| Exceeded IOM recommended gestational weight gain, N (%) | 74 (49.66) | 111 (67.68) | 0.0012 |

| Child Characteristics | |||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.86±1.79 | 38.74±2.43 | 0.62 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3211.30±551.00 | 3250.10±653.30 | 0.57 |

| Current Age (yrs) | 10.48±1.41 | 10.39±1.50 | 0.59 |

| Male sex, N (%) | 81 (54.36) | 91 (55.49) | 0.84 |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | 0.004 | ||

| NHW | 80 (53.69) | 61 (37.20) | |

| Hispanic | 62 (41.61) | 83 (50.61) | |

| AA | 7 (4.70) | 20 (12.20) | |

| Tanner stage ≥ 2, N (%) | 77 (46.95) | 87 (53.05) | 0.25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.80±3.31 | 20.34±5.14 | <0.0001 |

| Waist (cm) | 62.83±9.02 | 69.23±13.50 | <0.0001 |

| SAT (cm2) | 90.47±78.05 | 149.30±119.50 | <0.0001 |

| VAT (cm2) | 17.55±9.98 | 24.11±15.80 | <0.0001 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 82.72±37.91 | 93.51±43.80 | 0.02 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 52.72±9.44 | 50.46±11.14 | 0.06 |

| HOMA-IR | 36.69±26.92 | 52.52±39.95 | <0.0001 |

| Physical activity (blocks/day) | 4.52±2.93 | 3.88±2.88 | 0.05 |

| Total daily calories (kcal/day), mean (95%CI) | 1795.60±549.60 | 1839.40±531.30 | 0.47 |

| Percent calories from fat (%) | 35.99±5.11 | 36.20±4.80 | 0.70 |

Obesity defined as a BMI ≥ 30kg/m2

Results

Table I shows the characteristics of study population, according to maternal pre-pregnant obesity status. Of the 313 eligible mothers, 164 were classified as overweight or obese with a pre-pregnant BMI above 25 kg/m2. The groups were similar in terms of maternal age, parity status and gestational age at delivery. Women categorized as overweight or obese were more likely to be diagnosed with GDM compared with normal weight women, although not significantly (p=0.09). Maternal GWG patterns according to maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity status are also described in Table I. As expected, normal weight mothers gained significantly more weight in each trimester of pregnancy and overall, compared with overweight/obese mothers. However, 68% of overweight/obese mothers exceeded the 2009 GWG IOM recommendations versus only 50% of normal weight mothers (p<0.01).

Children in the two groups were similar in terms of age, sex and pubertal status, but significantly more offspring of overweight/obese mothers were of Hispanic or African American descent (p=0.004). All childhood adiposity measurements were significantly different according to maternal pre-pregnancy obesity status (Table I). Offspring of overweight/obese mothers had significantly higher BMI, waist circumference, as well as subcutaneous and visceral fat, compared with offspring of normal weight mothers. Triglycerides and insulin resistance, as estimated by risk HOMA-IR were also significantly worse for the children exposed to overweight/obesity in utero.

Table II shows the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and various offspring adiposity-related outcomes. The analysis is stratified by whether the mothers were meeting or exceeding the 2009 IOM recommendations for GWG. Increasing maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with significantly worse childhood outcomes in both GWG groups. However, the effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on several childhood outcomes was attenuated for offspring of mothers with adequate versus excessive GWG. This trend was observed for all explored variables, and was statistically significant for childhood BMI, waist circumference, SAT, and HDL-c. Additional adjustment for current diet and physical activity did not materially change the results.

Table 2.

The association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring outcomes, stratified by GWG status.*

| Adequate GWG | Excessive GWG | Interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) | β (95%CI) | p-value | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.13 (0.02, 0.253) | 0.34 (0.25, 0.44) | 0.004 |

| Waist (cm) | 0.38 (0.10, 0.65) | 0.83 (0.58, 1.08) | 0.01 |

| SAT (cm2) | 3.49 (0.89, 6.08) | 7.26 (4.90, 9.62) | 0.03 |

| VAT (cm2) | 0.37 (0.004, 0.74) | 0.72 (0.39, 1.06)- | 0.16 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 0.16 (−0.98, 1.31) | 1.12 (0.08, 2.16)- | 0.21 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 0.16 (−0.12, 0.44) | −0.34 (−0.60, −0.07) | 0.01 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.55 (−0.33, 1.43) | 1.66 (0.86, 2.45)- | 0.06 |

adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Tanner stage, birth weight and maternal GDM β = the 1 unit increase in offspring parameter for every 1 kg/m2 increase in maternal pre-pregnancy BMI p-values for each univariate model reported.

The Figure illustrates the relationship between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and childhood adiposity-related outcomes and the effect of adequate vs excessive GWG on this relationship. In each panel, the association of pre-pregnancy BMI and child outcome (BMI, waist circumference, SAT and HDL-c) is attenuated for offspring of mothers who gained adequate vs those who gain excessive gestational weight.

Discussion

In this cohort of over 300 mother-child pairs, women who were overweight or obese before their pregnancy were more likely to exceed the IOM recommendations compared with women who began their pregnancy at a normal BMI. Furthermore, higher pre-pregnancy BMI was associated with worse adiposity and metabolic risk markers in their offspring at an average age of 10 years, including higher BMI and waist circumference, SAT and VAT fat deposition, and abnormal lipid markers. Several of these relationships were significantly attenuated however, for offspring of women that gain the recommended amount of weight, as compared with those that gained excessive weight during pregnancy.

This analysis extends previous observations of an association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring adiposity outcomes later in life.11, 20, 21, 28, 29 A clear relationship between maternal weight status prior to pregnancy has been linked to offspring obesity as early as 2–4 years of age in a retrospective cohort of low income WIC participants11, in a national representative cross-sectional sample of 6–8 year olds20 and extended to early adolescence period in a prospective sample of over 200 Caucasian mother-child pairs.21 Various adiposity indicators in children have been explored including BMI percentile11, 20 and fat mass via dual X ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements.21 Offspring of mothers who had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 pre-pregnancy had a higher odds of being categorized as obese (≥ 95th percentile) at age 2 years (OR 2.2 (95% CI 1.8–2.6), 3 years (OR 2.6 (95% CI 2.2–3.1), and 4 years (OR 2.6 (95% CI 2.2–3.1).11 Similarly, for every one unit increase in maternal pregnancy BMI, fat mass measured by DXA rose by 0.26 (95% CI 0.04–0.48) in boys and 0.42 (95% CI 0.29–0.56) in girls at age 9 years.21

Several mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive may explain these associations. These include shared genes, shared familial socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, as well as specific intrauterine effects. Work, particularly from the Pima Indian population, suggests that the effect of maternal pregnancy diabetes on offspring obesity risk is not fully explained by genetic factors. In a small nuclear family study (52 families, 182 siblings) conducted in the Pima Indian population, obesity was greater among non-diabetic offspring born after the mother had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (i.e. overnutrition resulting from exposure to increased intrauterine glucose levels) than in their sibs born before their mothers' diagnosis (i.e. exposed to lower intrauterine glucose levels).30 In another study the prevalence of obesity among 2–18 year old siblings born after maternal biliopancreatic surgery was 52% lower than among age-matched siblings born when their mother was obese.31 Because siblings discordant for intrauterine exposures carry a similar risk of inheriting the same susceptibility genes, and share a similar postnatal environment, such studies provide strong evidence that part of the excess risk of childhood obesity associated with overnutrition in utero reflects specific intrauterine effects.

From a public health prevention perspective, distinguishing between specific intrauterine mechanisms and shared familial genetic/behavioral effects is essential for the development of randomized trials aimed at testing effective pregnancy interventions to reverse the obesity epidemic. In the absence of definite evidence provided by a randomized clinical trial this question can be tested by exploring whether GWG is a potential effect modifier of the relationship between maternal BMI and child outcomes. We found that adequate GWG significantly reduces the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring outcomes. For most childhood adiposity-related outcomes, the association with maternal pre-pregnancy BMI was still significant even if mothers gained the recommended amount of weight during pregnancy, likely reflecting the other causal pathways described above (shared familial genetic and non-genetic effects). However, all these associations were substantially reduced (by 50–60%) if women gained the recommended amount of weight during pregnancy. Of note, the inverse association between maternal BMI and offspring HDL-c levels observed with excessive weight gain during pregnancy became non-significant among the group who met the GWG recommendations.

Our study had numerous strengths including directly measured pregnancy exposures, state-of the art measures of childhood adiposity and the ability to readily explore associations between pregnancy exposures and childhood adiposity outcomes later in life. Limitations include the observational (rather than experimental) nature of the study and, likely, the relatively limited size of the cohort, which may have resulted in some non-significant interactions. We were underpowered to additionally explore whether insufficient GWG modifies the association between maternal BMI and offspring outcomes. However, the majority of research in this area has found no or little association between inadequate GWG and childhood risk of obesity.32 Finally, our cohort has oversampled women with GDM and thus our findings may not be completely generalizable to a lower risk population.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the effect of maternal pre-pregnancy BMI on several childhood adiposity-related outcomes is attenuated for offspring of mothers with adequate vs excessive GWG. Therefore, pregnant women should be encouraged to follow the IOM recommendations of weight gain for their given pre-pregnancy BMI. Finally, our study lends support for pregnancy interventions aiming at controlling GWG to prevent childhood obesity. Carefully designed randomized clinical trials are needed to determine whether improved weight gain patterns can be achieved throughout pregnancy that would prevent the short and long-term consequences on the offspring, and curb the obesity epidemic.

Figure 1.

GWG modifies the association between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and childhood adiposity-related parameters (Panels A–D).

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 DK068001).

Abbreviations

- NHW

non-Hispanic White

- BMI

body mass index

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- KPCO

Kaiser Permanente of Colorado Health plan

- U.S.

United States

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Yeh J, Shelton JA. Increasing prepregnancy body mass index: analysis of trends and contributing variables. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;193:1994–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, Schmid CH, Lau J, England LJ, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care. 2007;30:2070–6. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2559a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Okun N, Verma A, Mitchell BF, Flowerdew G. Relative importance of maternal constitutional factors and glucose intolerance of pregnancy in the development of newborn macrosomia. J Matern Fetal Med. 1997;6:285–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199709/10)6:5<285::AID-MFM9>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baeten JM, Bukusi EA, Lambe M. Pregnancy complications and outcomes among overweight and obese nulliparous women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:436–40. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Oken E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Field AE, Frazier AL, Gillman MW. Maternal gestational weight gain and offspring weight in adolescence. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;112:999–1006. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818a5d50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim J, Peterson KE, Scanlon KS, Fitzmaurice GM, Must A, Oken E, et al. Trends in overweight from 1980 through 2001 among preschool-aged children enrolled in a health maintenance organization. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1107–12. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemic of obesity in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:1650–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360:473–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Catalano PM. Obesity and pregnancy--the propagation of a viscous cycle? The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;88:3505–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pettitt DJ, Knowler WC. Diabetes and obesity in the Pima Indians: a cross-generational vicious cycle. J Obesity and Weight Regulation. 1988;7:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Whitaker RC. Predicting preschooler obesity at birth: the role of maternal obesity in early pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e29–36. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Koupil I, Toivanen P. Social and early-life determinants of overweight and obesity in 18-year-old Swedish men. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:73–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wrotniak BH, Shults J, Butts S, Stettler N. Gestational weight gain and risk of overweight in the offspring at age 7 y in a multicenter, multiethnic cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2008;87:1818–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Moreira P, Padez C, Mourao-Carvalhal I, Rosado V. Maternal weight gain during pregnancy and overweight in Portuguese children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:608–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oken E, Taveras EM, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;196:322, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Robinson CA, Cohen AK, Rehkopf DH, Deardorff J, Ritchie L, Jayaweera RT, et al. Pregnancy and post-delivery maternal weight changes and overweight in preschool children. Preventive medicine. 2014;60:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ensenauer R, Chmitorz A, Riedel C, Fenske N, Hauner H, Nennstiel-Ratzel U, et al. Effects of suboptimal or excessive gestational weight gain on childhood overweight and abdominal adiposity: results from a retrospective cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:505–12. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fraser A, Tilling K, Macdonald-Wallis C, Sattar N, Brion MJ, Benfield L, et al. Association of maternal weight gain in pregnancy with offspring obesity and metabolic and vascular traits in childhood. Circulation. 2010;121:2557–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hinkle SN, Sharma AJ, Swan DW, Schieve LA, Ramakrishnan U, Stein AD. Excess gestational weight gain is associated with child adiposity among mothers with normal and overweight prepregnancy weight status. The Journal of nutrition. 2012;142:1851–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.161158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Salsberry PJ, Reagan PB. Dynamics of early childhood overweight. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1329–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gale CR, Javaid MK, Robinson SM, Law CM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C. Maternal size in pregnancy and body composition in children. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;92:3904–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. National Academy of Sciences; Washington DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].National Diabetes Data Group Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and the other categories of glucose intolernance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039–57. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Growth and physiological development during adolescence. Annu Rev Med. 1968;19:283–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.19.020168.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Block G, Murphy M, Roullet J, Wakimoto P, Crawford P. T B. Pilot validation of a FFQ for children 8–10 years. The Fourth International Conference on Dietary Assessment Methods.2000. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pate RR, Ross R, Dowda M, Trost SG, Sirard J. Validation of a 3-day physical activity recall instrument in female youth. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2003;15:257–65. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hu HH, Nayak KS, Goran MI. Assessment of abdominal adipose tissue and organ fat content by magnetic resonance imaging. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2011;12:e504–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li C, Kaur H, Choi WS, Huang TT, Lee RE, Ahluwalia JS. Additive interactions of maternal prepregnancy BMI and breast-feeding on childhood overweight. Obesity research. 2005;13:362–71. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, Emmett PM, Ness A, Rogers I, et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2005;330:1357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38470.670903.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dabelea D, Pettitt DJ. Intrauterine diabetic environment confers risks for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity in the offspring, in addition to genetic susceptibility. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM. 2001;14:1085–91. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2001-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kral JG, Biron S, Simard S, Hould FS, Lebel S, Marceau S, et al. Large maternal weight loss from obesity surgery prevents transmission of obesity to children who were followed for 2 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1644–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nehring I, Lehmann S, von Kries R. Gestational weight gain in accordance to the IOM/NRC criteria and the risk for childhood overweight: a meta-analysis. Pediatric obesity. 2013;8:218–24. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]