Abstract

Objective

Lymphedema is a distressing and chronic condition affecting up to 30% of breast cancer survivors. Using a cross-sectional study design, we examined the impact of self-reported lymphedema-related distress on psychosocial functioning among breast cancer survivors in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. The WHEL Study has a dataset that includes self-report data on lymphedema status, symptoms and distress.

Methods

Chi-square tests and binary logistic regression models were used to examine how specific participant characteristics, including lymphedema-related distress, were associated with physical health and mental health as measured by the SF-36 and depressive symptoms assessed by the CES-Dsf.

Results

Of the 2,431 participants included in the current study population, 692 (28.5%) self-reported ever having lymphedema. A total of 335 (48.9%) women reported moderate to extreme distress as a result of their lymphedema and were classified as having lymphedema-related distress. The logistic regression models showed that women with lymphedema-related distress had 50% higher odds of reporting poor physical health (p=0.01) and 73% higher odds of having poor mental health (p<0.01) when compared to women without lymphedema. In contrast, even though lymphedema-related distress was significantly associated (p=0.03) with elevated depressive symptoms in the bivariate analyses, it was not significant in the logistic regression models.

Conclusion

Breast cancer survivors with lymphedema-related distress had worse physical and mental health outcomes than women with lymphedema who were not distressed and women with no lymphedema. Our findings provide further evidence of the relationship between lymphedema and psychosocial outcomes in breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: Breast cancer survivors, Lymphedema, Distress, Quality of life, Depressive symptoms, Oncology

INTRODUCTION

Lymphedema is a chronic condition faced by a significant percentage of breast cancer survivors. Of the 2.7 million breast cancer survivors, it is estimated that 6 to 30% of these women will experience lymphedema symptoms [1]. Further, the incidence of arm edema is estimated to be 26% (ranging from 0 – 56%) among breast cancer survivors [2]. Lymphedema usually arises as a result of damage to the lymphatic system near the affected breast region, impeding the flow of lymphatic fluid throughout the affected region and into the arm and/or hand. Depending on the severity of damage to the lymphatic system, the build-up of lymphatic fluid can cause a variety of symptoms. Common symptoms of lymphedema are arm or hand swelling, tenderness, numbness, puffiness, pain, and arm or hand heaviness [3–5]. Additionally, some women will experience serious complications related to lymphedema. Some examples of these complications are impairments in the local immune response, which can result in soft tissue infections with a high fever; cellulitis, which has been reported to occur in up to 63% of patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema; and adverse psychological and physical morbidity [5,6]. Also lymphedema can be a debilitating condition that negatively impacts an individual’s psychosocial functioning [7,8].

Previous research studies have shown that women living with breast cancer-related lymphedema experience a diminished quality of life [5,9–13]. In a study of 622 breast cancer survivors, women who self-reported arm or hand swelling had significantly lower mean scores on the mental and physical SF-12 subscales compared to women without swelling [13]. Using data from the Iowa Women’s Health Study, Ahmed and colleagues (2008) found that women with self-reported lymphedema (8.1% of the sample) and women with arm symptoms (37.2% of the sample) had lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) SF-36 scores compared to women without lymphedema or arm symptoms [9].

While the above studies demonstrate that diminished quality of life is a complication for breast cancer survivors living with lymphedema, a paucity of research studies have examined whether other psychological factors, such as depressive symptoms, are affected by lymphedema status. Oliveri and colleagues (2008) found that there was no difference in depression status as measured by the CES-D between women who reported arm/hand swelling and those who did not [11]. Additionally, Ridner (2005) found no association between CES-D scores between those with lymphedema and those without [12].

Although there is clear evidence that women with lymphedema have reduced quality of life, little is known about how distress attributed to lymphedema affects psychosocial functioning (i.e., quality of life and depressive symptoms). The main objective of this study is to investigate how lymphedema-related distress affects quality of life (i.e., physical and mental health) and depressive symptoms among breast cancer survivors enrolled in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study.

METHODS

Study Population

The WHEL Study was a randomized controlled trial that enrolled 3088 female breast cancer survivors to assess the effectiveness of a plant-based diet on breast cancer recurrence and mortality. All participants were within 4 years of an early stage breast cancer diagnosis categorized using American Joint Committee on Cancer (edition IV) criteria as stage I (≥1cm), stage II, or stage IIIA [14]. Between March 1995 and November 2000, seven study sites (four in California, one each in Arizona, Oregon, and Texas) recruited participants through physicians, tumor registries and community breast cancer events. As previously reported in 2007, the plant-based diet did not significantly alter rates of breast cancer recurrence or mortality for the study participants, who were followed for a median of 7.3 years [15].

Procedures

The majority of WHEL Study participants completed a series of self-administered questionnaires and in-person interviews at 5 standard study time points [baseline, 1 year, 2 or 3 years (randomly determined), 4 years, and 6 years]. These standard study time points were based on each participant’s date of enrollment. Additionally, WHEL staff contacted participants twice per year to collect information on a variety of health-related topics, such as health status and medical procedures. Details on all study protocols have been reported previously [14]. For this cross-sectional study, all data used in the secondary analyses, with the exception of the baseline participant characteristics and the lymphedema dataset, were collected during the Year 4 standard study time point. The Year 4 study time point is most closely associated with the lymphedema data collection time period, which was following the Year 4 and prior to the Year 6 study time point. The institutional review boards at each study site approved the procedures for this study.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

Demographic data were collected at baseline by a telephone screening interview and intake forms. To obtain tumor and treatment characteristics for each participant, medical records including pathology reports were reviewed. Documented variables include tumor grade and size, number of lymph nodes removed, and types of breast cancer treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and hormone therapy).

Body Mass Index

During the Year 4 study time point clinic visit, the participant’s height and weight were measured and used to calculate body mass index (BMI). For this study, BMI was categorized as underweight/normal weight (BMI < 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25 to 29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

Health Behaviors

Participants completed a questionnaire on their personal health habits, including smoking status and a validated 9-item physical activity scale [16]. Frequency, duration and intensity of physical activity were converted into metabolic units (METs) using a standard compendium in accordance with Ainsworth et al. [17]. As per Hong et al. (2007) and Bertram et al. (2011), the physical activity variable for the present analyses was based on total MET-hours per week (MHW) values with four categories: inactive (MHW < 3.3), mildly to moderately active (3.3 ≤ MHW < 10.0), active (10.0 ≤ MHW < 20.0) and highly active (MHW ≥ 20.0) [18,19].

Comorbid Medical Conditions

Participants were asked to provide self-report information on a variety of diseases/medical conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and gastrointestinal diseases. As per Patterson et al. (2010), comorbid medical conditions were grouped into general systems patterned after the validated Charleston comorbidity index to avoid overlapping diagnoses and to ensure adequate samples sizes in each group [20]. In total, there were 6 general system categories: arthritis, cardiovascular, diabetic, digestive, osteoporosis, and miscellaneous conditions. For the present analyses, participants were classified as having 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more comorbid medical conditions.

Psychosocial Outcomes

A self-administered 147-item questionnaire was completed by study participants to assess HRQOL and psychosocial functioning. This questionnaire included the SF-36-Item Health Survey (SF-36), and the 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale screening form (CES-Dsf). Previous studies have shown these measures to be valid and reliable assessments of quality of life and depressive symptoms among WHEL Study participants [21–23].

The SF-36 has 8 subscales: general health, physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical health problems, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role limitations caused by emotional problems, and general mental health. A physical health (PH) summary score was calculated from the general health, physical functioning, role limitations caused by physical health problems, and bodily pain subscales; and a mental health (MH) summary score was computed from the vitality, social functioning, role limitations caused by emotional problems, and general mental health subscales. The range of scores is from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health-related quality of life. The instrument has been widely used in research studies with breast cancer populations and shown to have strong psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75 to 0.91) [24–30]. Based on the previous WHEL analyses showing time to additional breast cancer events and all-cause mortality is associated with SF-36 PH scores in the lowest 2 quintiles [20,21], the PH and MH summary scores were divided into quintiles and categorized as “Poor” (bottom 2 quintiles) and “Moderate/High” (top 3 quintiles) for the present analyses.

The CES-Dsf is a self-report scale used to identify individuals with elevated depressive symptoms. The total score added from the 8-items can be converted into a logarithmic scale. It has been shown to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73) and valid in cancer patients [22]. For this study, total scores ≥ 0.06 in the logarithmic scale were categorized as elevated depressive symptoms; this cut-off point has been used previously as an indicator of clinically elevated depressive symptoms [22].

Lymphedema Dataset

Following the Year 4 standard study time point, WHEL staff contacted participants by telephone to assess lymphedema status. Each interviewed participant answered questions adapted from Norman and colleagues’ (2001) validated telephone lymphedema questionnaire [31]. To assess the participant’s experience with lymphedema, each woman was asked: 1) “Since your breast cancer treatment, was there ever a time when your arms or hands were different sizes from each other?”, and 2) “Since your breast cancer treatment, has a health care professional ever told you that you have lymphedema?”. Based on the answers to these two questions, women were grouped into two categories: 1) the lymphedema group consisted of women who answered “yes” to one or both of the questions and 2) the non-lymphedema group consisted of women who responded “no” or “not sure/don’t know” to both questions.

Additional questions were asked to any women who responded in the affirmative to either of the above two questions. These women were asked whether they had currently, previously, or never experienced the following 13 symptoms of lymphedema: swelling; tenderness; numbness; watches, rings, bracelets, clothing becoming tight on one side; puffiness; firm or leathery skin; pain; indentations in skin after leaning against something; difficulty in seeing knuckles or veins; tiredness, thickness, heaviness of hand or arm; difficulty holding or grasping objects; difficulty writing; and infection in the affected arm or hand. In addition, lymphedema-related distress was assessed by the question, “How much did/does your lymphedema distress or bother you?”, with 5 response choices. Women who selected “moderately”, “quite a bit”, and “extremely” were categorized as having lymphedema-related distress, and those who responded with “not at all” or “a little” were considered as having lymphedema without distress.

Statistical Methods

For this cross-sectional study, we conducted secondary analyses using bivariate associations to assess if participant characteristics, health behaviors, comorbid medical conditions, current lymphedema symptoms, and lymphedema-related distress were associated with each of the 3 psychosocial outcome measures (i.e., PH, MH, and depressive symptoms) separately. Chi-square tests were used to analyze the categorical variables. Any variables associated with PH, MH, and depressive symptoms at P<0.05 were included into the multivariate regression models. Binary logistic regression models were built separately for each outcome measure with variables shown to be statistically significant in the bivariate analyses added to the models as covariates. Significance for all analyses was set at P<0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics Version 20.0 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

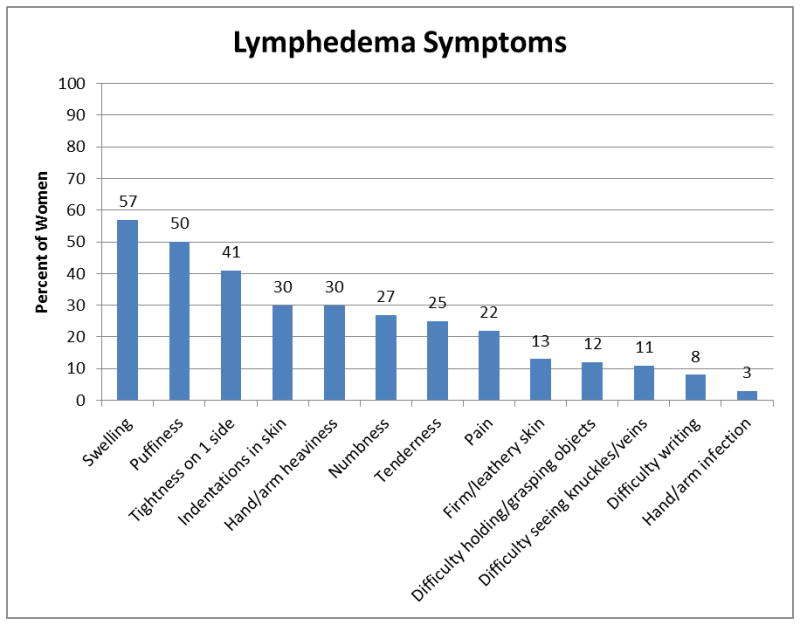

Of the 2917 WHEL participants contacted for the lymphedema assessment, 83% (N=2431) of the study cohort responded and self-reported their lymphedema status. Among these 2431 respondents, 692 (28.5%) women reported yes to either a physician’s diagnosis of lymphedema or arm/hand swelling. Of the 671 women who answered the lymphedema symptom questions, 71.7% of women were currently experiencing at least one symptom, and 44.2% of women reported experiencing four or more current symptoms. The three most common lymphedema symptoms were swelling (57%), puffiness (50%) and having watches, rings, bracelets, or clothing becoming tight on one side (41%) (Figure 1). Additionally, of the 685 women who answered the question, “how much did/does your lymphedema distress or bother you?”, 335 (48.9%) reported moderate to extreme distress as a result of their lymphedema and were classified as having lymphedema-related distress. Also there was a significant association between the number of current lymphedema symptoms and lymphedema-related distress [χ2 (3, N=671) = 56.96, p<0.01]. Of the 118 women who reported seven or more symptoms, 87 (73.7%) reported moderate to extreme distress as a result of their lymphedema.

Figure 1.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine how lymphedema-related distress and other participant characteristics were associated with physical health, mental health and depressive symptoms. The Physical Health (r=−0.258, n=2390, p<0.01) and Mental Health (r=−0.582, n=2389, p<0.01) summary scores were significantly correlated with the CES-Dsf scores. As shown in Table 1, lymphedema-related distress was significantly associated with PH, MH and depressive symptoms. Specifically, women who reported lymphedema-related distress were more likely to self-report poor PH, poor MH and elevated depressive symptoms as compared to those in the no lymphedema and lymphedema without distress groups. In terms of current lymphedema symptoms, trends towards poor PH (p=0.05) and poor MH (p=0.08) were found among those women reporting more symptoms. Additionally in the bivariate analyses, poor PH was significantly associated with the following 9 participant characteristics: age at diagnosis, ethnicity, education, marital status, BMI, menopausal status, chemotherapy, comorbid medical conditions, and physical activity. Poor MH was significantly associated with age at diagnosis, education, marital status, BMI, comorbid medical conditions, smoking status, and physical activity. Lastly, age at diagnosis, marital status, BMI, number of lymph nodes removed, comorbid medical conditions, smoking status and physical activity were significantly associated with elevated depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Lymphedema characteristics and their association with psychosocial health outcomes in a cohort of breast cancer survivors.

| Participant Characteristics | Physical Health | Mental Health | Depressive Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor PH N (%) |

P Value | Poor MH N (%) |

P Value | Elevated Depressive Symptoms N (%) |

P Value | |

| Lymphedema Distress | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.03 | |||

| No Lymphedema | 643 (37.1) | 654 (37.7) | 210 (12.2) | |||

| Lymphedema without Distress | 155 (44.7) | 143 (41.2) | 44 (12.8) | |||

| Lymphedema with Distress | 169 (50.8) | 173 (52.1) | 58 (17.6) | |||

| Current Lymphedema Symptoms (N=671) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.73 | |||

| 0 symptoms | 84 (44.2) | 80 (42.1) | 24 (12.8) | |||

| 1 to 3 symptoms | 76 (41.5) | 77 (42.1) | 30 (16.6) | |||

| 4 to 6 symptoms | 93 (53.1) | 89 (50.9) | 26 (14.9) | |||

| 7 or more symptoms | 64 (54.2) | 63 (53.8) | 19 (16.2) | |||

For the binary logistic regression models, the number of current lymphedema symptoms was not included due to its significant collinearity with lymphedema-related distress. The final PH model showed that women who reported lymphedema-related distress, being unmarried, overweight or obese, having 1 or more comorbid medical conditions, and being physically inactive were more likely to have poor physical health scores. Women who reported lymphedema-related distress had 50% higher odds of reporting poor PH compared to women in the no lymphedema group (Table 2). After adjusting for all variables in the MH model, women with poor MH scores were more likely to have lymphedema-related distress, have been diagnosed at age 50 and younger, be unmarried, have a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, have at least 1 or more comorbid medical conditions, and be physically inactive. As shown in Table 2, women with lymphedema-related distress had 73% higher odds of having poor MH when compared to women with no lymphedema. For the depressive symptoms final regression model, self-report of elevated depressive symptoms was significantly associated with being younger than 50 years at the time of cancer diagnosis, having 10 or fewer lymph nodes removed, having 1 or more comorbid medical conditions, being a current smoker, and being physically inactive. In contrast to the PH and MH models, lymphedema-related distress was not significantly associated with elevated depressive symptoms in the adjusted regression model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate-adjusted logistic regression models for physical health, mental health and depressive symptoms.

| Poor Physical Healtha (N = 1834) | Poor Mental Healthb (N = 1832) | Elevated Depressive Symptomsc (N = 1817) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N (%) |

OR | 95% CI | P value | Total N (%) |

OR | 95% CI | P value | Total N (%) |

OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Lymphedema Distress | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| No Lymphedema | 1318 (71.9) | 1.00 | 1317 (71.8) | 1.00 | 1306 (71.9) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Lymphedema without Distress | 260 (14.1) | 1.25 | 0.93–1.67 | 260 (14.2) | 1.14 | 0.86–1.52 | 258 (14.1) | 0.95 | 0.62–1.46 | |||

| Lymphedema with Distress | 256 (14.0) | 1.54 | 1.15–2.07 | 255 (14.0) | 1.73 | 1.31–2.30 | 253 (14.0) | 1.46 | 0.99–2.15 | |||

| Body Mass Index (YR 4) | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.23 | |||||||||

| < 25 kg/m2 (normal/ underweight) | 742 (40.5) | 1.00 | 742 (40.5) | 1.00 | 733 (40.4) | 1.00 | ||||||

| 25 – 29.9 kg/m2 (overweight) | 584 (31.8) | 1.33 | 1.04–1.71 | 583 (31.8) | 1.07 | 0.85–1.36 | 582 (32.0) | 1.27 | 0.88–1.85 | |||

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese) | 508 (27.7) | 2.41 | 1.85–3.14 | 507 (27.7) | 1.38 | 1.06–1.78 | 502 (27.6) | 1.38 | 0.94–2.02 | |||

| Comorbid Medical Conditions (YR 4) | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| 0 conditions | 690 (37.6) | 1.00 | 690 (37.7) | 1.00 | 688 (37.9) | 1.00 | ||||||

| 1 condition | 620 (33.8) | 1.54 | 1.20–1.96 | 619 (33.8) | 1.18 | 0.92–1.50 | 614 (33.8) | 1.22 | 0.84–1.75 | |||

| 2 conditions | 335 (18.3) | 2.77 | 2.05–3.74 | 334 (18.2) | 1.56 | 1.16–2.08 | 329 (18.1) | 1.66 | 1.09–2.54 | |||

| 3 or more conditions | 189 (10.3) | 3.02 | 2.09–4.38 | 189 (10.3) | 2.59 | 1.81–3.72 | 186 (10.2) | 1.98 | 1.20–3.26 | |||

| Physical Activity, METs-hour/week (MHW) (YR 4) | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Inactive (MHW < 3.3) | 393 (21.4) | 1.00 | 393 (21.5) | 1.00 | 389 (21.4) | 1.00 | ||||||

| Mildly-moderately Active (3.3 ≤ MHW < 10.0) | 389 (21.2) | 0.88 | 0.66–1.19 | 389 (21.2) | 0.72 | 0.33–0.59 | 385 (21.2) | 0.64 | 0.43–0.95 | |||

| Active (10.0 ≤ MHW < 20.0) | 466 (25.4) | 0.67 | 0.50–0.89 | 465 (25.4) | 0.63 | 0.47–0.84 | 459 (25.3) | 0.50 | 0.33–0.75 | |||

| Highly Active (MHW ≥ 20.0) | 586 (32.0) | 0.41 | 0.30–0.55 | 585 (31.9) | 0.44 | 0.33–0.59 | 584 (32.1) | 0.43 | 0.29–0.66 | |||

Physical health odds ratios were adjusted for age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, menopausal status, and chemotherapy.

Mental health odds ratios were adjusted for age at diagnosis, education, marital status, and smoking status.

Depressive symptoms odds ratios were adjusted for age at diagnosis, marital status, number of lymph nodes removed, and smoking status.

Additional exploratory analyses were conducted to examine associations within the lymphedema group. We re-ran the regressions models with the reference group defined as those with lymphedema without distress. Compared to the lymphedema without distress group, those with lymphedema-related distress had worse psychosocial outcomes OR (95% CI): 1.24 (0.85, 1.80) for the PH model, 1.52 (1.06, 2.18) for the MH model, and 1.54 (0.92, 2.57) for the depressive symptoms model. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to focus only on participants who reported a physician diagnosis of lymphedema and excluded those who reported only arm or hand swelling (i.e., a self-diagnosis of lymphedema). The ORs and significance levels for lymphedema-related distress categories of these restricted analyses were similar for the MH and depressive symptoms final logistic regression models. In the PH model the associations for both categories of lymphedema were significant OR (95% CI): 1.51 (1.05, 2.2) for the lymphedema without distress group; and 1.45 (1.04, 2.01) for the lymphedema with distress group.

DISCUSSION

The results of this cross-sectional study showed that lymphedema-related distress was associated with psychosocial functioning among women in the WHEL Study. After examining the relationship between current symptoms and distress specific to lymphedema, we found that the number of current lymphedema symptoms was highly correlated with reporting lymphedema-related distress. Further, our bivariate analyses findings showed that the number of current lymphedema symptoms as well as distress-specific to lymphedema were significantly associated with not only physical health, but with mental health outcomes as well. The results of our logistic regression models revealed that women with lymphedema-related distress had 50% higher odds of reporting poor physical health and 73% higher odds of having poor mental health when compared to women without lymphedema. In contrast, while lymphedema-related distress was significantly associated with elevated depressive symptoms in the bivariate analyses, it was not significant in the adjusted binary logistic regression models. However, lymphedema-related distress compared to no lymphedema was close to significant in the final model (OR=1.46; 95% CI 0.99, 2.15; p=0.06).

Our differences in the findings of the MH and depressive symptoms final regression models may be due to the fact that the MH summary score consists of multiple domains, which may better capture distress caused by lymphedema symptoms. Another explanation for the differences is that there were fewer cases of elevated depressive symptoms and hence the models for CES-Dsf may have been underpowered; the percentage of participants self-reporting poor MH was 38.3% compared to only 12.3% reporting elevated depressive symptoms. Clinicians should be aware that patients with lymphedema may experience both PH and MH challenges.

Other studies have examined the impact of lymphedema on quality of life as measured by the SF-36 or SF-12 among breast cancer survivors [9–11,13,32–34]. Similar to our study findings, the majority of these studies have shown that women with lymphedema have significantly lower PH summary scores than women without lymphedema [9–11,13,32,33]. These findings are important when considering that poor PH has been shown to be associated with decreased time to additional breast cancer events and all-cause mortality [21]. However, it should be noted that we did not find a significant association between lymphedema and additional breast cancer events or all-cause mortality (data not shown).

Further, we have confirmed findings in multiple studies showing that women with breast cancer-related lymphedema have lower MH summary scores on the SF-36 and SF-12 [9,11,13,34]. In contrast to our study findings, two studies found no significant differences in SF-36 MH summary scores between those with lymphedema compared to those without breast cancer-related lymphedema [32,33]. These differences in MH findings may be due to participant demographics, sample size, or study objectives, which may influence how participants were selected. Both of these previous studies had small lymphedema populations (< 50 women), which may limit the power to detect clinically meaningful results. These studies found statistically significant lower mean scores in women with lymphedema in all SF-36 subscales, except the mental health subscale. Yet the mental health subscale scores were lower for those with lymphedema when compared to those without lymphedema, which may suggest a lack of power.

While our study findings for HRQOL measured by the SF-36 in breast cancer survivors with lymphedema support the results from other studies, the main difference between our study and other studies was our focus on examining how self-reported distress attributable to lymphedema impacts PH and MH outcomes. It should be noted that for both the PH and MH models, adding lymphedema-related distress to a model that included the variables in Table 2 increased the Nagelkerke R-squared by < 1%. The other variables shown in Table 2 (i.e., physical activity, body mass index, and comorbid medical conditions) explained 18% of the total variance in both the PH and MH models. However, knowledge that lymphedema-related distress is associated with poor MH and PH is important for counseling breast cancer survivors with this condition. Another difference between our study and others was how we chose to categorize the SF-36 PH and MH summary scores. Our study followed the work of Saquib and colleagues (2011) in categorizing the PH and MH summary scores into quintiles with the bottom two quintiles for each summary score representing either “poor physical health” or “poor mental health” [21]. Scores were grouped into quintiles to allow for ease of interpretation and to rank study participants as to not assume the cut-points for the study population. The other studies discussed above used mean PH and MH scores to describe HRQOL among breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. Regardless of how the PH and MH summary scores were analyzed, our results are similar with these studies in showing that breast cancer survivors with lymphedema have significantly poorer mental and physical health when compared to those without lymphedema.

Due to the dearth of research studies that have examined elevated depressive symptoms measured by the CES-Dsf in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema, ours is the first large, population-based study to report no significant differences in CES-Dsf scores in multivariate models between breast cancer survivors with lymphedema compared to those without lymphedema. However, in the bivariate analyses, we found there to be a significant association between elevated depressive symptoms and lymphedema-related distress (P=0.03). After examining the proportion of variance explained for the depressive symptoms models, we found that lymphedema-related distress explained only a small proportion of the variance; whereas, physical activity was the largest contributor to the proportion of variance. Other studies have found no significant differences in depressive symptoms scores when comparing breast cancer survivors with lymphedema compared to those without lymphedema [11,12].

The main strength of our study is the use of lymphedema-related distress as a means of determining how lymphedema impacts psychosocial functioning among our study population. Another study strength is its large sample size of women reporting lymphedema (N=692). Most studies examining the psychosocial impact of lymphedema in breast cancer survivors have had fewer than 100 participants reporting lymphedema symptoms [7,8,10–12,32–34]. Another study strength is its comprehensive dataset on tumor and treatment variables, health behaviors, comorbid medical conditions, and psychosocial factors.

In contrast to the study strengths, the primary limitation of this present study is its reliance on self-report for many of the study variables, including lymphedema status. However, the assessment of lymphedema was obtained through the use of a validated questionnaire that has been shown to accurately identify lymphedema in breast cancer survivors [31]. Further, the study outcome variables (i.e., PH, MH, and depressive symptoms) were collected using valid and reliable instruments. For example, the SF-36 has been used in numerous breast cancer survivorship studies to assess HRQOL [8,9,21,23,32,35]. Bardwell and colleagues (2004) confirmed that response bias did not influence the accuracy of the SF-36 scores in the WHEL Study [23]. Also previous studies have shown the CES-Dsf to be a useful measure to identify elevated depressive symptoms in cancer survivors [8,22]. It should be noted that WHEL Study participants were mostly White, well-educated, and volunteered to be part of an intense dietary intervention; therefore, the study results may not be generalizable to other breast cancer populations. Also distress attributed to lymphedema in this study may be related to other factors and there is no way to ascertain “all-cause” distress. Further, due to the cross-sectional nature of the lymphedema assessment, we cannot comment on the causative relationships between lymphedema and the study outcome variables.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the negative psychosocial impact of lymphedema-related distress among breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer survivors with lymphedema-related distress had worse physical and mental health outcomes compared to women with lymphedema without distress and women with no lymphedema. These findings are in line with and support previous studies showing that breast cancer survivors with lymphedema report lower health-related quality of life. This study adds to the literature the importance of assessing distress caused specifically by lymphedema when studying breast cancer-related lymphedema. Also future research should develop tailored health behavior interventions to improve psychosocial functioning among breast cancer survivors distressed by their lymphedema.

Acknowledgments

The WHEL Study was initiated with the support of the Walton Family Foundation and continued with funding from National Cancer Institute grant CA 69375. Some of the data were collected from General Clinical Research Centers, National Institutes of Health grants M01-RR00070, M01-RR00079, and M01-RR00827. Research related to the development of this paper was supported by Award Number T32-GM084896 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. Study investigators would like to thank all WHEL Study participants who contributed time and effort to this research.

References

- 1.Petrek JA, Heelan MC. Incidence of breast carcinoma-related lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83(12 Suppl American):2776–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12b+<2776::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA, Adams J, Kahn KL. Arm edema in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(2):96–111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrell RM, Halyard MY, Schild SE, Ali MS, Gunderson LL, Pockaj BA. Breast cancer-related lymphedema. Mayo Clinic. 2005;80(11):1480–4. doi: 10.4065/80.11.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman SA, Localio AR, Potashnik SL, Simoes Torpey HA, Kallan MJ, Weber AL, et al. Lymphedema in breast cancer survivors: incidence, degree, time course, treatment, and symptoms. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):390–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakorafas GH, Peros G, Cataliotti L, Vlastos G. Lymphedema following axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2006;15(3):153–65. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shih YCT, Xu Y, Cormier JN, Giordano S, Ridner SH, Buchholz TA, et al. Incidence, treatment costs, and complications of lymphedema after breast cancer among women of working age: a 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(12):2007–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paskett ED, Dean JA, Oliveri JM, Harrop JP. Cancer-related lymphedema risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, and impact: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3726–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.8574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu MR, Ridner SH, Hu SH, Stewart BR, Cormier JN, Armer JM. Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: A systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(7):1466–84. doi: 10.1002/pon.3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed RL, Prizment A, Lazovich D, Schmitz KH, Folsom AR. Lymphedema and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(35):5689–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nesvold I-L, Reinertsen KV, Fosså SD, Dahl AA. The relation between arm/shoulder problems and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;5(1):62–72. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0156-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveri JM, Day JM, Alfano CM, Herndon JE, Katz ML, Bittoni MA, et al. Arm/hand swelling and perceived functioning among breast cancer survivors 12 years post-diagnosis: CALGB 79804. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(4):233–42. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridner SH. Quality of life and a symptom cluster associated with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(11):904–11. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0810-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paskett ED, Naughton MJ, McCoy TP, Case LD, Abbott JM. The epidemiology of arm and hand swelling in premenopausal breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(4):775–82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierce JP, Faerber S, Wright FA, Rock CL, Newman V, Flatt SW, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of a plant-based dietary pattern on additional breast cancer events and survival: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23(6):728–56. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298(3):289–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson-Kozlow M, Rock CL, Gilpin EA, Hollenbach KA, Pierce JP. Validation of the WHI brief physical activity questionnaire among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(2):193–202. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong S, Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, Flatt SW, Rock CL, Newman VA, et al. Correlates of physical activity level in breast cancer survivors participating in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101(2):225–32. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertram LAC, Stefanick ML, Saquib N, Natarajan L, Patterson RE, Bardwell W, et al. Physical activity, additional breast cancer events, and mortality among early-stage breast cancer survivors: findings from the WHEL study. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:427–35. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9714-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Saquib N, Rock CL, Caan BJ, Parker BA, et al. Medical comorbidities predict mortality in women with a history of early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122(3):859–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saquib N, Pierce JP, Saquib J, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Bardwell WA, et al. Poor physical health predicts time to additional breast cancer events and mortality in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(3):252–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, Dimsdale JE, Rock CL, Mortimer JE, Hollenbach K, et al. Objective cancer-related variables are not associated with depressive symptoms in women treated for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(16):2420–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bardwell WA, Major JM, Rock CL, Newman VA, Thomson CA, Chilton JA, et al. Health-related quality of life in women previously treated for early-stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(9):595–604. doi: 10.1002/pon.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin PJ, Black JT, Bordeleau LJ, Ganz PA. Health-related quality-of-life measurement in randomized clinical trials in breast cancer--taking stock. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(4):263–81. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry S, Kowalski TL, Chang CH. Quality of life assessment in women with breast cancer: benefits, acceptability and utilization. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:32. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrans CE. Differences in what quality-of-life instruments measure. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;2007(37):22–6. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golden-Kreutz DM, Thornton LM, Wells-Di Gregorio S, Frierson GM, Jim HS, Carpenter KM, et al. Traumatic stress, perceived global stress, and life events: prospectively predicting quality of life in breast cancer patients. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):288–96. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norman SA, Miller LT, Erikson HB, Norman MF, McCorkle R. Development and validation of a telephone questionnaire to characterize lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer. Phys Ther. 2001;81(6):1192–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson RW, Hutson LM, Vanstry D. Comparison of 2 quality-of-life questionnaires in women treated for breast cancer: the RAND 36-Item Health Survey and the Functional Living Index-Cancer. Phys Ther. 2005;85(9):851–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawes DJ, Meterissian S, Goldberg M, Mayo NE. Impact of lymphoedema on arm function and health-related quality of life in women following breast cancer surgery. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(8):651–8. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velanovich V, Szymanski W. Quality of life of breast cancer patients with lymphedema. Am J Surg. 1999;177(3):184–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pusic AL, Cemal Y, Albornoz C, Klassen A, Cano S, Sulimanoff I, et al. Quality of life among breast cancer patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments and outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):83–92. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0247-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]