Abstract

Objectives

Latinos with disabilities disproportionately report substance use, including binge drinking and drug use. Ecodevelopmental factors, including socioeconomic patterning of poverty, social exclusion and post-colonial racism, have been shown to impact alcohol and drug use. However, this line of research remains under-developed among Latinos with disabilities. The purpose of this study was to obtain rich descriptions of the role of ecodevelopmental factors, including family and community, on alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities.

Methods

We utilized a community-based participatory research design, in conjunction with an innovative methodology referred to as photovoice. Three rounds of photography and focus group interviews were conducted with a total of 17 focus groups. Reflections in each focus group interview were aloud and digitally audiotaped. A total of 28 participants 19–35 years of age (mean age= 27.65, SD= 5.48) participated in each round of photography and focus group interviews. Data analyses followed the tenets of descriptive phenomenology.

Results

Findings highlight ecodevelopmental family and community risk and protective factors. At the family level, participants reflected on the ways in which family functioning, including family support, communication and cohesion, can serve as risk and promotive factors for alcohol and drug use. Additionally, participants described in detail how experiences of poverty, stigma and discrimination, violence, accessibility to alcohol and drugs, accessibility for persons with disabilities, transportation, community support and cohesion, and access to health and mental health services constitute risk and promotive factors at the community level.

Conclusion

Findings are suggestive of how ecodevelopmental family and community factors might increase the risk for alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities. From this qualitative research, we derive a series of testable hypotheses. For example, future studies should examine the impact of family functioning on alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities over time. Study findings may have great utility to inform the development of preventive interventions for this at-risk group.

Keywords: Latino/Hispanic, disability, substance use, photovoice, community-based participatory research, ecodevelopmental

Introduction

Persons with physical disabilities are disproportionately impacted by alcohol and drug use (Ebener and Smedema, 2011; Smedema and Ebener, 2010). Alcohol and drug abuse rates among persons with disabilities in the U.S. are estimated to be between 20% and 40%, as compared to approximately 10% in the general U.S. population (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2009). Of persons with disabilities who report having drank alcohol, up to 50% report binge drinking (DHHS, 2009). Latinos with physical disabilities may be at increased risk of alcohol and drug use (Cordova et al., 2013; Turner, et al., 2006). For example, Latinos with physical disabilities (5.00) are more likely to report past year drug abuse, relative to their non-Latino white (4.72) and African American (4.25) counterparts (Turner et al., 2006). Despite the public heath need to ameliorate alcohol and drug use health disparities, scientists and service providers have yet to fully take up this task – especially with regard to persons with disabilities, the largest minority group in the nation (Brault, 2008). Indeed, this is even truer among Latinos with physical disabilities (Cordova et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2006).

Family and community ecological risk factors can increase risk for alcohol and drug use. For example, communities characterized by poverty (Hannon and Cuddy, 2006), violence (Krug et al., 2002), social isolation, discrimination and stigma (Ahern et al., 2007), increased availability and access to alcohol and drugs (Redmond and Spooner, 2009), and lacking access to culturally responsive health and mental health care (Kuehn, 2012), can increase risk for alcohol and drug use. However, these studies have not focused on persons with physical disabilities, nor have they been interpreted from an ecodevelopmental framework. Latinos with physical disabilities might be at increased risk of experiencing ecological risk factors, relative to their non-Latino white counterparts (Institute of Medicine, 2007; Lezzoni, 2011), yet the theoretical and empirical literature remain under-developed (Cordova et al., 2013; McMahon et al., 2011). We sought to address this gap in the literature through qualitative methodology.

Prevention science affirms the importance of taking an ecological approach to better understand the etiology of alcohol and drug use (Cordova et al., 2011; Hawkins et al., 1992). Building on the work of Bronfenbrenner (1979), the ecodevelopmental framework (Szapocznik and Coatsworth, 1999) is a risk and protective factors framework that is helpful in conceptualizing integrated ecological processes (Paquette and Ryan, 2001). These processes, from proximal to distal, include micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems that impact and are impacted by the individual. The ecodevelopmental framework expands on risk and protective factors heuristic models by also considering developmental processes and social interactions of interrelated domains (Coatsworth and Szapocznik, 1999). For the purposes of this study, we utilized the ecodevelopmental framework as a heuristic model to help guide our study and focus on family and community microsystems. Microsystems refer to the most proximal systems in which the individual operates. Family ecodevelopmental processes can include family communication and support, whereas community ecodevelopmental factors can include accessible transportation and health care. The purpose of this study was to obtain a detailed description of the role of family and community ecodevelopmental factors on alcohol and drug use in Latinos with physical disabilities.

Methods

Study Design

This study was guided by the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). We established a community advisory board (CAB) in an effort to (a) ensure community members could contribute to the advancement of knowledge, (b) establish trust with community members, (c) facilitate recruitment, engagement and retention of participants, and (d) ensure that research findings accurately described participants’ ecology (Isreal et al., 2005; Minkler and Wallerstein, 2003).

Sampling and Recruitment

The study was conducted from May 2008 through April 2010 and was approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board.

The study population was Latinos with physical disabilities aged 18–35 residing in Service Planning Area 7, Los Angeles, California. We defined physical disability as a physical impairment that limited the individual’s ability to perform normal and daily activities, with a minimum duration of at least 3 months (Turner, et al., 2006). Participants must have reported past year1 alcohol or drug use as indicated by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health-past year Substance Use or past year Binge Drinking (SAMHSA, 2007).

Potential participants were recruited via the CAB and the research team through face-to-face presentations and distribution of fliers. Word-of-mouth and snowballing methods were employed (Umaña-Taylor and Bámaca, 2004). A list was created of potential participants who expressed interest to participate in the study and were either called by the first author via phone or met face-to-face to screen for eligibility criteria. A total of 28 participants were included in this study and stratified by gender.

Procedures

We employed photovoice in the collection of data, an innovative CBPR methodology effective in capturing in-depth descriptions of ecodevelopmental processes through shared diverse meanings associated with collected photographs (Foster-Fishman et al., 2010; Wang and Redwood-Jones, 2001). Photovoice (Wang & Burris, 1994, 1997) aims to empower marginalized populations by placing cameras in the hands of participants to better understand lived experience. Informed by Freire’s pedagogy of the oppressed, feminist theory and photographic imagery framework, photovoice provides an opportunity for participants to increase awareness of their ecology and work toward social change (Carlson, Engebretson, & Chamberlain, 2006). We employed the photovoice methodology as described by Wang and Burris (1994, 1997). To facilitate discussion of photographs, focus group interviews were utilized. Focus groups have the potential to facilitate cohesion among participants as they share similar ecodevelopmental processes, as well as generating data that cannot be generated through individual interviews (Stewart et al., 2007; Umaña-Taylor & Bámaca, 2004). Focus groups may be limited in that there is the potential for group interviews to be dominated by one participant. The utilization of focus group discussions for verbal-elicitation of participants’ reflections with regard to their photos has been used in previous photovoice studies (e.g., Cooper & Yarbrough, 2010; Foster-Fishman et al., 2010). We conducted three rounds of photography and focus group interviews (Wang and Burris, 1994, 1997). Each round was conducted every four weeks to ensure adequate time for picture taking, collection of cameras, film processing, participant reflection and the implementation of the focus group interviews. We repeated these procedures in the second round, limiting the third round to only a focus group interview. Although the majority of participants stayed within the same group across all three rounds of interviews, some participants joined another focus group that best fit their schedule.

After completing a training session on the ethical mandates of photovoice, participants were given a camera and instructed to take photos based on the grand tour questions, “Describe your life experiences as a Latino/a with a disability particularly as it relates to substance use,” and “What are your family/community risk and protective factors as a Latino with a disability as it relates to substance use?” The first two rounds of focus group interviews promoted a process of reflexivity with respect to the participants’ ecodevelopmental context (Porter, 1995; Wang and Redwood-Jones., 2001) and lasted approximately two hours. During the first hour, each participant shared with the group three photos. During this time, each participant reflected on how they made sense of the photographs in a focus group discussion. Once each member of the group shared their three photos, the group collectively voted on three photos that most accurately described their collective ecodevelopmental context. Ecodevelopmental risk and protective factors associated with these photos were discussed in-depth during the second hour of the focus group discussion. As such, the photographs were utilized to facilitate each focus group discussion. The third round of focus groups focused on member checks (Morrow, 2005). Because participants were interviewed multiple times, themes from the first round of interviews informed the subsequent rounds of interviews. For example, in the first round of focus group discussions, participants shared experiences of discrimination (i.e., being Latino). Participants were then given a second camera to take photos and prepare for the second round of focus group discussions. In the second round, and based on the first round of focus group discussions, participants shared additional contexts (e.g., work, health professionals) and identities (i.e., disability, substance user) in which they experience discrimination. As such, the longitudinal nature of conducting multiple interviews with the same participants facilitated in-depth conversations (Porter, 1994), as well as increased consciousness of issues related to social justice (Carlson et al., 2006). Participants’ responses were targeted to all members of the focus group discussion, including the facilitator and focus group discussion participants (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Focus groups (n=17) ranged in size from 2 to 7 participants. Traditionally, the recommended size for focus group discussions ranges from 6–8 participants; however, smaller groups may produce more in-depth insights particularly when seeking to understand lived experience among Latinos (Umaña-Taylor & Bámaca, 2004), and studies with focus groups consisting of two participants with Latino populations have been reported elsewhere (Cordova et al., 2013; Parra-Cardona et al., 2008). In the first round of focus group discussions (n=7), one focus group discussion consisted of 7-, 6- and 5- participants each, and two focus group discussions consisted of 2 and 3 participants each, respectively. In each of the second (n=5) and third (n=5) rounds of focus group discussions, two focus group discussions consisted of 6 participants each, and one focus group discussion consisted of 4-, 3-, and 2- participants each, respectively. In each of the three rounds of focus group discussions, two groups consisted of women, two groups of men, and the remaining groups of mixed gender. Participants were assigned to focus groups based on convenience, with the exception of gender specific groups. No significant differences were found on any of the demographic variables between participants who did and did not participate in all three rounds. Data collection took place over the course of 20 weeks.

Analytic Approach

We transcribed the audiotapes of the 17 focus groups verbatim and reviewed the transcripts for accuracy. Once all data were transcribed, we conducted a detailed analysis of family and community ecodevelopmental data according to the descriptive phenomenological approach (Porter, 1995). Descriptive phenomenology has its roots in philosophical principles that emphasize the need to privilege human experience by describing the experiences of people as lived and understood by them (Husserl, 1970). This analytic approach complements the photovoice and focus group data collection methodology as all aim to understand lived experience, and photovoice serves as a method to elicit phenomenological data when researching the lived experience (Cordova et al., 2013; Plunkett, Leipert, & Ray, 2013). For the purposes of this study, we only present ecodevelopmental data. Details on lived experience of Latinos with physical disabilities are reported elsewhere (Cordova et al., 2013). Data were categorized into elements, descriptors, and features (Porter, 1995).

Bracketing and Reflexivity

After identifying the most relevant ecodevelopmental (i.e., life-world) data, and confirming with participants in the third round of focus group interviews that such descriptions accurately describe their most relevant life experiences, a process of “filling out” was implemented (Porter, 1995). In descriptive phenomenology, this process refers to ensuring that findings are not affected by the researcher’s preconceived notions and ideas. Prior to analyzing the data of this study, the research team examined data that where “bracketed” prior to data collection and analysis (Porter, 1994). Bracketing consists of working towards identifying and monitoring preconceived ideas and biases in order to participate in the data collection and data analysis with an open mind (Porter, 1995). Bracketing consisted of conducting a thorough literature review and the first author writing and sharing with the research team a personal narrative, both of which are aimed at monitoring preconceived ideas. Essentially, through the literature review, our pre-understanding of the study was that Latinos with physical disabilities experience health and mental health inequities, including substance use. Additionally, iterations of the data analysis were presented to participants and the CAB to obtain their feedback, and emerging themes were presented to the CBO and CAB during the collection of data. Reflexivity refers to identifying the social location of the research team as well as monitoring emotional responses to participants which shapes the interpretation of the participants’ narratives (Mauthner and Doucet, 2003). To promote reflexivity, a number of methods were employed, including bracketing (Porter, 1994) and journaling (Morrow, 2005). For example, after each focus group interview, the first author engaged in journaling and described instances in which he was reactive with respect to oppressive ecological contexts, as well as the ways in which his own personal life experiences are similar and contrasting to participants’ reflections. Such reflections allowed the first author to understand certain pre-conceived notions with regard to Latinos with physical disabilities (e.g., Latinos with disabilities operate through multiple oppressed identities and contexts that influence alcohol and drug use). We used NVivo 8 software to complete all qualitative data analyses (QSR International, 2008).

Results

Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics on participants’ demographics, disability classification and alcohol and drug use, respectively.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Total n=28 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (50%) |

| Female | 14 (50%) |

| Disability classification | 14 (50%) |

| Difficulty lifting heavy objects | 6 (21.4%) |

| Difficulty bending | 4 (14.3%) |

| Uses a wheelchair | 4 (14.3%) |

| Visual impairment | 4 (14.3%) |

| Hearing impairment | 3 (10.7%) |

| Limited leg movement | 3 (10.7%) |

| Amputation | 2 (7.1%) |

| Limited arm movement | 2 (7.1%) |

| Nativity Status | |

| United States-born | 23 (82.1%) |

| Foreign-born | 5 (17.9%) |

| Generational status | |

| First-generation Latino | 10 (35.7%) |

| Second-generation Latino | 9 (32.1%) |

| Third-generation Latino | 2 (7.1%) |

| Unknown generation Latino | 7 (25%) |

| Primary language | |

| English | 17 (60/7%) |

| Spanish | 9 (32.1%) |

| Bilingual | 2 (7.1%) |

| Educational attainment | |

| Elementary school | 18 (64.3%) |

| High school | 4 (14.3%) |

| Some college | 6 (21.4%) |

| Employment status | |

| Full time | 6 (21.4%) |

| Part time | 1 (3.6%) |

| Unemployed looking for work | 12 (42.9%) |

| Unemployed not looking for work | 6 (21.4%) |

| Unemployed due to disability | 2 (7.1%) |

| Other | 1 (3.6%) |

| Combined annual family income | |

| <$10,000 | 12 (42.9%) |

| $10,001–$25,000 | 5 (17.9%) |

| $25,001–$35,000 | 2 (7.1%) |

| >$35,001 | 2 (7.1%) |

| Don’t know | 7 (25%) |

Table 2.

Past year alcohol and drug use

| Total n=28 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Binge drinking | 21 (75%) |

| Marijuana (non-medical) | 10 (35.7%) |

| Methamphetamine | 9 (32.1%) |

| Cocaine | 8 (28.6%) |

| Crack | 3 (10.7%) |

| Ecstasy | 3 (10.7%) |

| Heroin | 2 (7.1%) |

| Other hallucinogens | 2 (7.1%) |

| PCP or angel dust | 1 (3.6%) |

| LSD or acid | 1 (3.6%) |

| Inhalants | 1 (3.6%) |

| Benzodiazepine | 1 (3.6%) |

| Vicodin (non-prescription) | 1 (3.6%) |

The analytical process led to the identification of 309 elements. Of these, 5 ecodevelopmental themes were identified (Table 3): (a) ecodevelopmental family risk, (b) ecodevelopmental family protection, (c) ecodevelopmental community risk, (d) ecodevelopmental community protection, and (e) ecodevelopmental health and mental health risk.

Table 3.

Analytic process

| Research Questions | Features | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| What are the ecodevelopmental risk factors in the lives of Latinos with Disabilities who report substance use? | Being Put Down by my Family | My family trying to help me but in the wrong way Not being able to ask my family for help. My family not trusting me |

| Being Challenged by my Community | Being impacted by poverty, violence and gangs I’m invisible to others Drugs and alcohol all around me Being discriminated against: as a Latino with a disability |

|

| Experiences with Health and Mental Health Professionals and Service Providers | Not having access to mental health Being stigmatized for receiving mental health services Being put down by service providers Service providers lacking cultural sensitivity |

|

| What are the ecodevelopmental protective factors in the lives of Latinos with Disabilities who report substance use? | Being Supported by my Family | My family being there for me and loving me My family not feeling sorry for me My family giving me strength not to use drugs |

| Being Supported by my Community | Community understanding what I’m going through My community embracing my culture My community reaching out to me and helping me |

|

Ecodevelopmental Family Risk

Participants (n=20) shared photographs of family to describe the ways in which family context can be a challenge with respect to their disability and alcohol and drug use. Participants described the following descriptors: (a) my family trying to help me, but in the wrong way, (b) not being able to ask my family for help, and (c) my family not trusting me.

My family trying to help me, but in the wrong way (n=20)

Participants reflected on feeling “put down” by their family through various forms of “negativity,” an experience that may increase their risk for alcohol and drug use. One female participant who reported difficulty lifting heavy objects described the significance of this challenge and how this may contribute to drug use:

The kind of pain I endured was rejection from my family. A lot of negativity from my family and that always contributed to my drug use… It’s really painful to not be able to be with your family or to not have your family accept you or love you.

Another female participant who reported limited leg movement reflected and shared a photograph symbolizing the challenges of family context:

When my family puts me down, it’s caused me so much pain… the relationship I have with my father has caused me so much grief and pain… And it’s always brought on this whole ‘screw it’ attitude…And then I go and seek that love and comfort from things that aren’t good for me like drugs, men, or anything just to feel accepted or loved.

Not being able to ask my family for help (n=16)

Latinos with disabilities described that one of the most difficult challenges for them is asking others for help, particularly because of past experiences in which they have reached out to family members for help and experienced rejection in return. One male, visually impaired participant stated:

Tomorrow I have an appointment right here at general hospital and it’s stressful because I can’t ask my family. Honestly, I don’t want to ask them because I know the stupidity they are going to come out with.

My family not trusting me (n=19)

A significant challenge reported by participants refers to mistrust from their families, particularly with respect to their efforts to stop substance use. One female, hearing impaired participant expressed:

I wish they would really just believe me. Cause right now that I’m staying away [from drugs]…They just don’t believe me and it really bothers me…I just really wish they would believe me when I tell them.

Ecodevelopmental Family Protection

Participants (n=22) shared experiences of strong family support, including feeling loved and encouraged by family members, which served as a protective factor. The following descriptors represent the ways in which participants felt supported: (a) my family being there for me and loving me, and (b) my family giving me strength not to use drugs.

My family being there for me and loving me (n=21)

Participants photographed family members and reflected on having felt supported by their families. Various forms of support included emotional, financial, mutual responsibility, and help with completing daily activities of living. One male participant who reported being hearing impaired reflected:

How has my family supported me? Pretty much letting me stay at my mom’s house even though she kicked me out before. I kind of burned her in different ways, taking stuff or money… she still took me back in her home and she still had love for me… I guess she just had that hope for me and never gave up on me… My family just being there for me and showing me love.

Participants shared photos to describe how supported they felt when family members provided assistance for them with daily activities of living. One male participant who utilizes a wheelchair shared:

My strength is my mom and my dad cause without them I wouldn’t be anything. Thanks to God I have them both cause either my mom or my dad, in the morning whenever I need to wake up, as you guys know I have to wear a diaper. And they go change me and all that. They take me a bath.

My family giving me strength not to use drugs (n=20)

Participants shared photographs and described how being responsible for family members served as a motivation to stop their alcohol and drug use. One female participant who reported limited arm movement mentioned:

My family helps me not to use drugs… My dad doesn’t want me to get high. He’s like, “Well what if you go out there and get high and don’t come back? What about the kids and what about me.” So he doesn’t want me to get high.

Ecodevelopmental Community Risk

Participants (n=28) reflected on photos suggestive of an ecology characterized by multiple community risk factors, which contribute to alcohol and drug use. The theme, “Ecodevelopmental community risk,” was defined through the following descriptors: (a) being impacted by poverty, violence, and gangs, (b) drugs and alcohol all around me, and (c) I’m invisible to others.

Being impacted by poverty, violence and gangs (n=28)

A constant reminder to participants with respect to poverty is the electronic benefits transfer (EBT) signs advertised throughout their community. EBT is a government supplemental assistance benefit. One female participant who reported difficulty bending expressed (see fig. 1):

I notice that in barrios and hoods, the EBT stamp is everywhere … wherever there is a minority, like Latinos or African American communities, it’s everywhere … Even in the [store] you can pay with your EBT card. But when you go to a different neighborhood with more Caucasians, you don’t see these around … It kind of makes me feel like Latinos are poor.

Figure 1.

Ecodevelopmental Community Poverty Risk.

Participants described how they have experienced community violence. One female participant who reported difficulty lifting heavy objects reflected:

I took pictures of where I live and what I’ve been exposed to and how one of my friends died. He was only 21 years old. And he just got shot in the day light right in the front. That’s really sad.

Drugs and alcohol all around me (n=28)

Participants reflected on their community characterized by the high accessibility to alcohol and drugs. One male participant who reported being hearing impaired described (see fig. 2):

This is a picture of a market. It’s like plastered in beer signs and pretty much just shoving it in your face. There’s even little neon signs just flashing. It’s just being pushed on you, to buy beer. I see that there’s just lots of times and places in the community that you’re being tempted and pressured to drink, smoke or do drugs.

Figure 2.

Ecodevelopmental Community Alcohol Advertisement Risk.

I’m invisible to others (n=21)

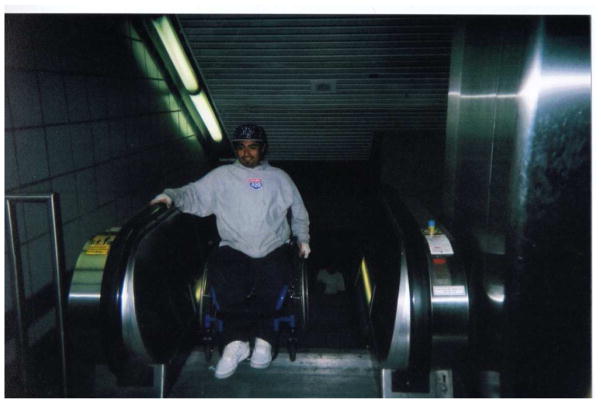

Participants reflected on the ways in which lack of accessibility for Latinos with physical disabilities constitutes a significant challenge and that many locations throughout the community are not accessible. One male participant who utilized a wheelchair shared a photo (see fig. 3):

I sometimes have to use the electrical ones [escalators]. I don’t know how to go down really … I need to learn how to do that. I know that to go up, I’m going to need help… That’s one of them, well one of my beefs. Learning how to go up the stairs and going down the stairs on my wheelchair.

Figure 3.

Ecodevelopmental Community Lacking Accessibility Risk.

Participants shared photos representing public transportation and described that they are being negatively impacted by lack of accessibility. They described the limitations of public transportation, particularly when critical routes for them were not offered. One male participant with an amputation shared (see fig. 4):

I don’t have access to services everywhere. I’m limited to places they take me. Like right there where I go to therapy, they can’t take me. There’s no bus to take me out there.

Figure 4.

Ecodevelopmental Community Access to Transportation Risk.

Being discriminated against as a Latino with a disability and substance use (n=21)

Participants shared photos describing the ways in which they experience discrimination. One male visually impaired participant reflected:

It sucked being discriminated against. I was 8 years blind already and I wanted to change my life so bad. And I got information about the [institute]. They were going to teach me how to walk with a cane, teach me how to use a computer, a bunch of things. And these people just judged me by my looks. They stopped me from getting this information.

Another female participant who reported difficulty bending reflected on her experiences of discrimination:

Everybody thought I was a gangster…I think the stereotypes for Latina women, either we’re whores or we’re cholas [Latina female gang member]… There can never be strong, good Latina women.

Participants shared photos of their disability and discussed the stigma attached to having a disability, and how they perceive disability as shunned by the community. One female participant with limited leg movement shared, “For a lot of people in the community, disability is shunned and we just get the doors closed on us.”

Participants reflected on how they experience stigma for their alcohol and drug use, which perpetuates their use. One female participant who reported limited arm movement described, “It’s hard because people tend to think that they can disrespect you. People that don’t use alcohol and drugs think they are better than you. They think you are worthless, that you’re nothing.”

Participants shared how people lack an understanding of their alcohol and drug use because they overlook how ecodevelopmental challenges influence alcohol and drug use. One female participant who reported difficulty lifting heavy objects reflected:

I know it’s just a label when they say, “Them addicts, all they care about is getting high.” And that’s not true. They don’t look at what affects us. They don’t look at our consequences. They don’t look at what’s come before us. All they look at is just that label. And the label says a lot in one shot. Just being an addict mother with a disability says a lot… people don’t look at the way we’ve grown up, or how.

Ecodevelopmental Community Protection

Participants (n=18) elaborated on the various sources of support in their community. The theme, “Ecodevelopmental community protection,” was defined through the following descriptors: (a) my community understanding what I’m going through, (b) my community embracing my culture, and (c) my community reaching out to me and helping me.

My community understanding what I’m going through (n=18)

Participants described how members of the community who express an understanding of their experiences constitute a source of strength to help combat alcohol and drug use. One male amputee participant described, “Right there in my apartments, they understand that I have a disability… It’s cool. They’re cool and a lot of people understand me. They understand what I’m going through.”

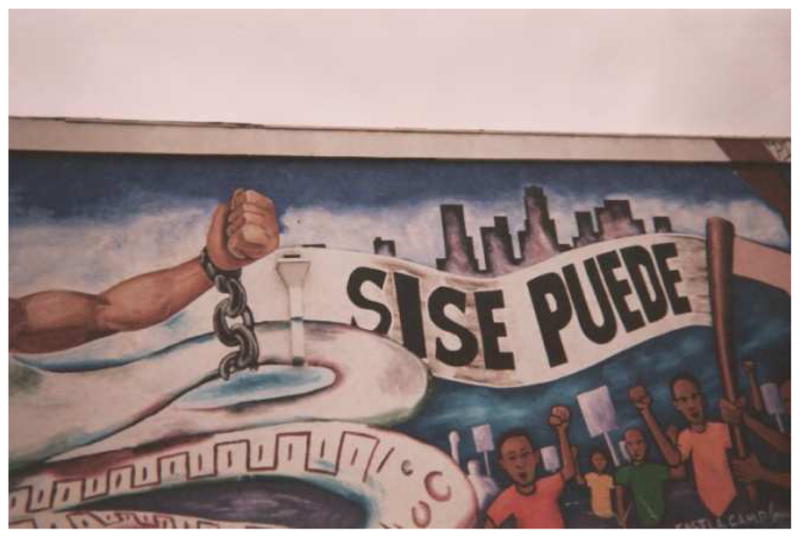

My community embracing my culture (n=18)

Participants described how they felt supported by their community because of the open recognition and value of the Latino culture. One female participant who reported difficulty lifting heavy objects reflected (see Fig. 5):

In the community, you have the art work…the neighborhood is about brown pride … at the park, they always have family things … they always have celebrations, the night outs, and they make it safe for the community … Everybody has a spot to go to the park and the tamales are right there … They always have the big fairs and they make it seem like it’s a Latino thing.

Figure 5.

Ecodevelopmental Community Culture Representation Protection.

Participants shared a strong sense of community cohesion and the collectivistic nature of the community which represents one key value of the Latino culture. One female participant who reported difficulty bending shared:

I think there is still some sort of respect in our community… I’ve had neighbors that I’ll send them a plate of food and then the next day they’ll send me a plate of food. We are there for each other… we can be really united as a people when we want to be.

My community reaching out to me and helping me (n=17)

Community resources constitute a critical source of support for participants. One male participant who reported difficulty lifting heavy objects expressed, “To know that there is that extra support out there, it’s awesome, it’s great.”

Ecodevelopmental Health and Mental Health Risk

Participants (n=17) shared negative experiences with health and mental health professionals and service providers. Descriptors for this ecodevelopmental context include: (a) not having access to mental health, (b) being stigmatized, and (c) being put down by service providers.

Not having access to mental health (n=17)

Not having access to mental health care, including lacking financial resources and health insurance, constituted a challenge for participants (n=17) which negatively influenced drug and alcohol use. One male participant who utilized a wheelchair reflected, “They ain’t going to do nothing for free, you know? Anywhere you go, they want to see your Medi-Cal, Medicare, or money. They won’t do nothing for free.”

Being stigmatized (n=17)

Participants reported a fear of receiving mental health services because of the stigma attached to receiving services. One female participant who reported difficulty bending shared:

It is taboo, in our community if you go to therapy, you’re crazy. Something’s wrong with you… we are taught at an early age or it’s programmed into our head, that if you go to some kind of therapy, you are nuts… There’s something wrong with you.

Being put down by service providers (n=16)

Participants reflected on photos describing being put down by service providers. One male visually impaired participant described:

These people work and they even have a disability and they act like if they are buying the things out of their own pocket. They won’t help you get your things in time. They don’t try to support you a lot. I had a lot of problems with them too. My state rehab counselor held me back for so many months to get the tools that I need for my disability.

Participants expressed professionals and service providers lacking understanding and cultural responsiveness with regard to disability and alcohol and drug use. One female participant who reported limited arm movement stated:

The thing that I would probably relay to them is them knowing substance use… Sometimes, social workers could not relate or have no idea of what disability is about. Maybe having them be more aware of what disability and addiction is all about.

Discussion

Findings suggest that Latinos with physical disabilities experience significant family and community ecodevelopmental risk factors that may increase risk for alcohol and drug use. Additionally, participants provided descriptions of protective factors which could be targeted to reduce alcohol and drug use in this population.

The Role of Ecodevelopmental Family Risk

Given the proximity of family, combined with the salient and central theme of family in Latino cultures, participants frequently chose to photograph their families. Findings suggest that an environment characterized by ineffective family communication and cohesion may play a significant role in alcohol and drug use among Latinos with disabilities. Interventions aimed at preventing alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities could focus on improving family communication, especially with regard to alcohol and drug use in the context of physical disability and Latino culture. Indeed, research has demonstrated that family-based preventive interventions are among the most efficacious for Latino populations (Sandler et al., 2011; Szapocznik et al., 2007). However, there currently are no efficacious alcohol and drug use preventive interventions tailored to meet the needs of Latinos with physical disabilities. Future research should work toward the development and evaluation of a culturally responsive, family-based preventive intervention for this population.

The Role of Ecodevelopmental Community Risk

In addition to describing challenges that perhaps all members of the community might experience (e.g., poverty, violence), participants described community challenges that might be more likely to play a role in Latinos with physical disabilities, including accessibility. Lack of accessibility for participants served as a constant reminder of how they experience social isolation, which could play a role in alcohol and drug use. Moreover, participants reflected on experiences of discrimination and stigma for identifying as an ethnic minority, having a physical disability, and for their alcohol and drug use (Austin et al., 2004; Koch et al., 2002). Research suggests that both mental and physical health in alcohol and drug users are impacted by stigma, discrimination and alienation (Ahern et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2012). Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which ecodevelopmental community risk factors impact alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities. Understanding these mechanisms is of public health importance for developing community-based, ecodevelopmental alcohol and drug use preventive interventions aimed at promoting community action and mobilization. From a policy perspective, there remains the need for structural policies aimed at reducing the cumulative effects of ecodevelopmental risk. Policies are needed to provide Latinos with physical disabilities with the necessary means to reduce their experiences of isolation, stigma and discrimination (Livingston et al., 2012) which can be as effective as traditional interventions aimed at reducing alcohol and drug use (Sullivan, 2003).

The Role of Ecodevelopmental Health and Mental Health Risk

Findings demonstrate the participants’ strong desires to seek out health and mental health services yet experiencing multiple barriers, including lack of cultural responsiveness, outreach and engagement, and stigma which prevented them from seeking out services. Unfortunately, ways of coping with this structural exclusion included the use of alcohol and drugs. Thus, it appears that these structural and policy barriers play a significant role in alcohol and drug use among Latinos with disabilities. Studies have indicated that inequities exist with respect to having access to and having received treatment for health and mental health among Latinos (Fox et al., 2007) and persons with disabilities (Reichard, et al., 2011), as well as the effects of lacking access to health and mental health care on alcohol and drug use (Kuehn, 2012). Future research should work toward a better understanding of the effects of lacking access to health and mental health care on drug and alcohol use in this population over time.

The Role of Ecodevelopmental Family and Community Protection

Findings demonstrate the need to remain attentive to the role of ecodevelopmental protective factors operating in the lives of participants. Participants reflected and identified family and community strengths. These strengths served to validate the participants’ experiences and facilitate engagement of participants to family and community contexts, and thereby may serve as a protective role in preventing and reducing alcohol and drug use. These reflections should constantly inform prevention approaches adopted by researchers and service providers committed to supporting this population.

Expanding the Ecodevelopmental Framework to Latinos with Physical Disabilities

The ecodevelopmental framework (Szapocznik & Coatsworth, 1999) provided a conceptual framework to help guide this study and work toward a fuller understanding of family and community ecological risk and protective factors operating in the lives of Latinos with physical disabilities. The accumulative effect of multiple ecological risks (e.g., poverty, violence) experienced by participants, combined with multiple marginalized identities (i.e., minority status), may make substance use more pronounced in this population (Cordova et al., 2013). Future research should examine this conceptual framework using a longitudinal design.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, a purposive sample was used in this study design. The sample is not representative of the U.S. Latinos with physical disabilities population, and the results might not have transportability to all Latinos with physical disabilities. Additionally, potential selection bias may constitute a threat to the generalizability of the findings. The participants’ ecology in this study may differ from those in other communities. Finally, the reliance on self-report measures of alcohol and drug use might be vulnerable to social desirability effects (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Notwithstanding these limitations, the methodology employed in this study design suggests that CBPR approaches might be an effective way to recruit and engage this understudied population.

Key Messages.

Researchers have documented that Latinos with physical disabilities in the USA experience alcohol and drug use health inequities, and have highlighted the importance of identifying risk and protective factors to inform prevention and health promotion in this population.

Prevention scientists have demonstrated the role family and community ecodevelopmental factors play in the etiology of alcohol and drug use among the general population, yet the research among Latinos with physical disabilities remains underdeveloped. Study findings provide evidence that in addition to experiencing family and community ecodevelopmental factors that may affect all individuals in the targeted community, Latinos with physical disabilities may experience additional risk factors that are unique to this population.

Our study contributes evidence of the importance of understanding family and community ecodevelopmental factors associated with alcohol and drug use. Findings contribute to the literature in working toward a fuller understanding of the complexities associated with identifying as an ethnic minority, having a disability, and alcohol and drug use aimed at the development of best practice knowledge for this population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapists Minority Fellowship Program; the Dissertation Completion Fellowship, School of Social Science, Michigan State University; and the Verna Lee and John R. Hildebrand Dissertation Fellowship, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, to David Cordova. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Loan Repayment Program under Grant 1L60MD006269-01, and National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grant R25 DA026401 06 to David Cordova. We thank the courageous participants in this study who willingly shared their life stories. We also thank the community advisory board members and community partners for their support throughout the implementation of this study.

Footnotes

We initially had past 30-day alcohol or drug abuse as the inclusion criteria. However, many potential participants were reluctant to participate because they were receiving services that were contingent on them not using alcohol or drugs. By participating in this study, they would in fact disclose their alcohol or drug use. Therefore, the CAB suggested past year alcohol or drug use as the inclusion criteria.

References

- Ahern J, Stuber J, Galea S. Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin JK, MacLeod J, Dunn DW, Shen J, Perkins SM. Measuring stigma in children with epilepsy and their parents: instrument development and testing. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2004;5(4):472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault M. Americans with Disabilities: 2005, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2008. pp. 70–117. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ED, Engebretson J, Chamberlain RM. Photovoice as a social process of critical counsciousness. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:836–52. doi: 10.1177/1049732306287525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CM, Yarbrough SP. Tell Me—Show Me: Using Combined Focus Group and Photovoice Methods to Gain Understanding of Health Issues in Rural Guatemala. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(5):644–653. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, Huang S, Arzon M, Freitas D, Malcolm S, Prado G. The role of attitudes, family, peer and school on alcohol use, rule breaking and aggressive behavior in Hispanic delinquent adolescents. The Open Family Studies Journal. 2011;4:38–45. doi: 10.2174/1874922401104010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdova D, Parra-Cardona JR, Blow A, Johnson D, Prado G, Fitzgerald H. The role of intrapersonal factors on alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. doi: 10.1080/1533256X.2013.812007. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebener DJ, Smedema SM. Physical disability and substance use disorders: A convergence of adaptation and recovery. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 2011;54(3):131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman PG, Law KM, Lichty LF, Aoun C. Youth ReACT for social change: A method for youth participatory action research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;46:67–83. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V. Gender differences in drug treatment careers among clients in the national drug abuse treatment outcome study. The American Journal of Drug Alcohol and Abuse. 1999;25(3):383–404. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon L, Cuddy MM. Neighborhood ecology and drug dependence mortality: an analysis of New York City census tracts. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32(3):453–63. doi: 10.1080/00952990600753966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DJ, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other substance problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husserl EG. The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Northwestern Univ Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) The Future of Disability in American. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Isreal BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Scholenber JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent druge use: Overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research. The University of Michigan; 2012. p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Koch DS, Nelipovich M, Sneed Z. Alcohol and other drug use and coexisting disabilities: Considerations for counselors serving individuals who are blind or visually impaired. Re:View. 2002;33(4):151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. WHO documents worldwide need for better drug abuse treatment--and access to it. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(5):442–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezzoni L. Eliminating health and health care disparities among the growing population of people with disabilities. Health Affairs. 2011;30(10):1947–1954. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, Amari E. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: A systematic review. Addiction. 2012;107(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-Based Participatory Research for Healths. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow SL. Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(2):250–260. [Google Scholar]

- National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women. Changing perceptions of sexual violence over time. Washington, DC: McMahon, S., & Baker, K; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D, Ryan J. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory: Culture. 2001 Retrieved from http://cms-kids.org/providers/early_steps/training/documents/bronfenbrenners_ecological.pdf.

- Plunkett R, Leipert BD, Ray SL. Unspoken phenomena: using the photovoice method to enrich phenomenological inquiry. Nursing Inquiry. 2013;20:156–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2012.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter EJ. Older widows’ experience of living alone at home. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1994;26:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter EJ. The life-world of older widows: The context of lived experience. Journal of Women and Aging. 1995;7:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. Nvivo, Getting Started. 2008 Retrieved August, 8th, 2012, from http://www.qsrinternational.com/FileResourceHandler.ashx/RelatedDocuments/DocumentFile/289/NVivo8-Getting-Started-Guide.pdf.

- Redmond G, Spooner C. Alcohol and other drug related deaths among young people in CIS countries: Proximal and distal causes and implications for policy. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2009;20(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichard A, Stolzle H, Fox MH. Health disparities among adults with physical disabilities or cognitive limitations compared to individuals with no disabilities in the United States. Disability and Health Journal. 2011;4(2):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Schoenfelder EN, Wolchik SA, MacKinnon DP. Long-Term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:299–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedema SM, Ebener D. Substance use and psychosocial adaptation to physical disability: analysis of the literature and future directions. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010;32(16):1311–1319. doi: 10.3109/09638280903514721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DW, Shamdasani PN, Rook DW. Focus groups: Theory and Practice. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CM. Using the ESID model to reduce intimate male violence against women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32:295–303. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004749.87629.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth D. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and prevention. In: Glantz Meyer D, Hartel Christine R., editors. Drug abuse: Origins and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew AK, Williams RA, Santisteban DA. Drug abuse in African American and Latino adolescents: Culture, development, and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:77–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health. Racial disparities in adolescent health and access to care. 1. Washington, DC: Fox, H. B., McManus, M. A., Zarit, G. F., Cassedy, A. E., Bethell, C. D., & Read, D; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, Taylor J. Physical disability and mental health: An epidemiology of psychiatric and substance disorders. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2006;51(3):214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Bámaca MY. Conducting focus groups with Latino populations: Lessons from the field. Family Relations. 2004;53(3):261–272. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Office on Disability. (2009) Substance abuse and disability. 2012 Sep 17; Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/od/about/fact_sheets/substanceabuse.html.

- Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):171–186. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Redwood-Jones YA. Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from Flint Photovoice. Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28(5):560–572. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]