Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most serious health problems worldwide. Many researchers have investigated HCC at the level of genes, ribonucleic acid, proteins, cells, and animals. The resultant development of animal models and monitoring methods has improved the effectiveness of guidelines provided to researchers working with preclinical HCC models. HCC in animal models and clinical patients is monitored by various current imaging modalities such as ultrasound (US) imaging, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET) and bioluminescence imaging (BLI). These techniques are currently used for both preclinical and clinical assessment, and provide valuable diagnostic information. In this article, we have mainly reviewed the established animal models and the assessment of orthotopic HCC using imaging modalities. Additionally, we have introduced a method of orthotopic HCC rat model developed in our laboratory. We have furthermore evaluated the occurrence of tumor mass using molecular imaging techniques.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatoma, Orthotopic HCC, McA-7777, N1S1, Cyclosphorin A, Molecular imaging

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most serious health problem worldwide, with an incidence of 782,000 newly diagnosed cases and 746,000 liver-cancer-related deaths estimated in 2012 [1–4]. HCC is caused by liver cirrhosis due to advanced hepatitis B and C (HBV, HCV) viral infection and has been increasing around the globe [5–7].

Clinical advances for HCC have occurred in various fields of clinical surgery, liver transplantation, radioimmuno/radiation therapy, biological therapy and bio-molecular imaging [8]. Even though the study of HCC invasiveness has advanced at the molecular level with overall sophisticated breakthroughs in knowledge of HCC, it has not translated to improved HCC patient care [9].

Given the large HCC patient population, there is a strong sense of responsibility to develop relevant animal models and appropriate detection methods, applicable to preclinical research, as well as clinical trials for developing new treatments for HCC. Investigation of HCC has been done conducted at the level of genes, ribonucleic acid (RNA), proteins, cells, and animals [10–14]. The resultant development of animal models and monitoring methods has improved the effectiveness of guidelines provided to researchers working with preclinical HCC models. Furthermore, technical approaches and alternate strategies have advanced to assess prognostic values in clinical trials, as well as the efficacy and safety of anticancer drugs in the preclinical field. One such strategic approach is the application of bio-molecular imaging techniques to preclinical and clinical studies.

Research techniques have made it possible to estimate the rate of tumor occurrence, the size, growth and response to treatments, as well as to confirm the results of histology and/or immunohistochemistry, in case of HCC where molecular imaging cannot be performed. Modeling and validation methods are very important in preclinical studies of HCC. Therefore, several molecular imaging methods, which include computed tomography (CT), ultrasound (US) imaging in radiology, positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in nuclear medicine, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) in biology, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) in histology, are commonly employed in preclinical research and in designing clinical trials [15–19]. Moreover, in an effort to establish the orthotopic HCC animal models, methodological challenges involving the use of various cell lines, with or without premedication such as an immunosuppressant, and different selections of HCC cell lines have been introduced by several laboratories worldwide [20–23]. When performing in vivo experiment on HCC, scientists start with subcutaneous xenograft or orthotopic models. Subcutaneous xenograft models provide an easy and simple means to implant tumor cells into the animal and to monitor the progress of the tumor size. On the other hand, the orthotopic animal models provide more highly informative clinical translation than subcutaneous xenograft models through the biological and metastatic microenvironment similar to clinical status. Thus, orthotopic animal models of HCC are required for more reliable translation in specific tumor circumstances.

In this article, we have mainly reviewed how to establish orthotopic HCC animal models, and assess orthotopic HCC occurrence and incidence by means of several molecular imaging modalities. In addition, we have described our experimental efforts in developing a rodent model of orthotopic HCC including the data on incidence of cancer development to provide our experience to other researchers who have similar interests, and extend our findings to the professional field.

Cell Lines

Preclinical research usually involves an animal model of HCC to evaluate therapeutic effects on HCC. Additionally, various human or animal HCC cell lines are used to study comparative viability, apoptosis, and toxicity in response to test substances [24]. Typically, Hep 3B, Hep G2, Huh 7.5 and SK-Hep1 in human HCC cell lines and N1S1 and McA-RH7777 in rat HCC cell lines are commonly used in HCC models [25–30].

Subcutaneous Xenograft and Orthotopic Animal Models

After the results of in vitro examinations are acquired, in vivo studies are performed to identify the relationship between the HCC and the cellular microenvironment, as well as the interaction of HCC cells and the targeted organ [31]. When scientists perform in vivo studies, they usually begin with subcutaneous xenograft animal models, by injecting selected cells into subcutaneous space of the interest area within the body. This method is practical, since it is easy to handle the animal and monitor the progress of the tumor models [32].

On the other hand, in the orthotopic models of HCC, the cancer cells are directly inoculated into the liver parenchyma, such as left lower segment of liver. The orthotopic implantation experimental methods have been sometimes considered as labor-intensive, because it required surgical inoculation and it was difficult to measure the tumor growth, or to validate therapeutic effect on post-treatment of tumor growth [33]. Orthotopic animal models, nevertheless, provided highly valuable clinical information, including tumor growth rate, therapeutic effect of tested materials, and in vivo tumor cell behaviors because the tumor is located within the targeted organ [34]. Moreover, orthotopic models also contribute to developing original therapeutic and molecular imaging techniques [35].

Introduction of Various Research Studies Using HCC Animal Models

A large number of scientists have performed their exclusive work using the HCC animal model induced by human and/or animal HCC cell lines. One example of the use of human cell lines was a study by, Yao et al. [25] who designed a mouse model of orthotopic HCC, by inoculation of Hep 3B human cell lines directly into the liver parenchyma. They showed periodical tumor survival rate, assessed by H&E staining and laparotomy, for 8 weeks. Ma et al. [26] showed significant therapeutic effect of a recombinant adenovirus contained a truncated-Bid gene induced by α-fetoprotein (Ad/AFPtBid) in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in the orthotopic HCC model. Their model used SK-Hep1 or Hep 3B human cell lines in culture, inoculated in mice, which represents natural occurrence. Vongchan et al. [27] used HCC models with Hep G2 cell lines in their study that demonstrated and characterized the inhibition of both tumor progression, and proliferation of liver cancer in vitro and in vivo. Chandra et al. [28] used Huh 7.5 cell lines to design xenograft mouse models. They evaluated the inhibition of hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication by small interfering RNA (siRNA) encapsulated into lipid nanoparticles (nanosomes). Their results indicated that systemic injections of siRNA nanosomes significantly reduced replication of liver cancer in HCC xenograft mouse models of HCV.

Cho et al. [29] designed HCC rat models with McA-RH7777 isolated from the Buffalo rat and achieved a high tumor incidence (73.3%). Moreover, they successfully treated hepatoma with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in all rat models. Buijs et al. [30] used N1S1 or McA-RH7777 rat cell lines to characterize tumor growth of HCC, and they assessed each cell line derived tumor of by US imaging technique in rat models. The result of their experiments showed that tumor volumes in both cell line groups continued to increase until 2 weeks post-inoculation and then started to decrease considerably. Complete tumor regression was shown at 5 or 6 weeks post-inoculation in the N1S1 and McA-RH7777 groups. In summary, the basic information on referred HCC cell lines is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information of HCC cell lines

| Type | Name | Purchased from | Culture medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Hep 3B | American Type Culture Collection | Minimum Essential Medium |

| (Manassas, VA) | (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) | ||

| Hep G2 | CLS Cell Lines Service | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium | |

| (Eppelheim, Germany) | (Gibco, Invitrogen, NY) | ||

| Huh 7.5 | The Laboratory of Charlie Rice | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium | |

| (The Rockefeller University, NY) | |||

| SK-Hep 1 | American Type Culture Collection | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium | |

| (Rockville, MD) | (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) | ||

| Rat | N1S1 | American Type Culture Collection | Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium |

| (SD Rat) | (Manassas, VA) | ||

| McA-RH7777 | American Type Culture Collection | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium | |

| (Buffalo Rat) | (Manassas, VA) | (WelGENE, Daegu, Korea) |

HCC Assessment by Bio-molecular Imaging

HCC in animal models and clinical patients of HCC were monitored by various imaging methods for preclinical and clinical assessment with valuable diagnostic information [15–18]. The most commonly used imaging modalities are US, CT with contrast agent, MRI and 18F-FDG-PET/CT [36]. These imaging techniques provide valuable information on tumor progression and therapeutic effect in both preclinical and clinical circumstances.

US imaging, especially, has been commonly used in both preclinical and clinical researches to monitor progression of liver tumors and to assess the antitumor therapeutic effects. In addition, US imaging is able to support the target destruction by high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) with a highly concentrated drug delivery system to the tumor lesion in clinical trials [37].

The use of both 18F-FDG-PET/CT and MRI has increased, as well as CT imaging. However, 18F-FDG-PET/CT and MRI are more difficult to be processed due to its high diagnostic costs, and high skill requirement for image acquisition and diagnosis [38].

BLI, which is a novel imaging technique for the detection of luminescence emitted from the expression of luciferase genes in living cells, has provided a valuable method for preclinical research, but was not useful for clinical trials due to the limited translational benefits [39]. BLI also was beneficial in monitoring orthotopic animal models of invisible tumors [40].

Effect of Immunosuppressants in Tumor Growth

Cyclosporin A (CsA) is a known immunosuppressant used in various types of transplantation [41]. The survival of grafts and patients has considerably increased since the introduction of CsA [42]. Its efficacy was also reported in various in vitro and in vivo research studies [43]. However, CsA also enhanced the growth of tumor that was susceptible to immune-competent cells and paradoxically led to the development of specific cancers. For instance, Hammond-Mckibben et al. [44] studied three types of immunosuppressive agents: CsA, 40-O-(2-hydroxyethyl)rapamycin (SDZ RAD), and 2-amino-2-[2-(4-octyl-phenyl)ethyl]-1, 3-propanediol hydrochloride (FTY720). They demonstrated that administration of SDZ RAD or FTY720, together with CsA, resulted in more effective dose-dependent inhibition of tumor regression in an allogeneic xenograft mouse model. In addition, Van de Vrie et al. [45] showed that the CsA enhanced loco-regional metastasis of tumor but improved short-term antitumor activity in their experiment using CC531, the colon carcinoma cell line of rat models.

Establishment of the Orthotopic HCC Rat Model

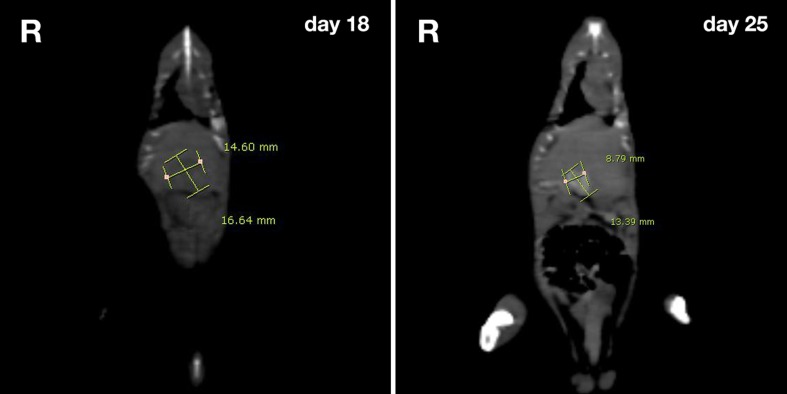

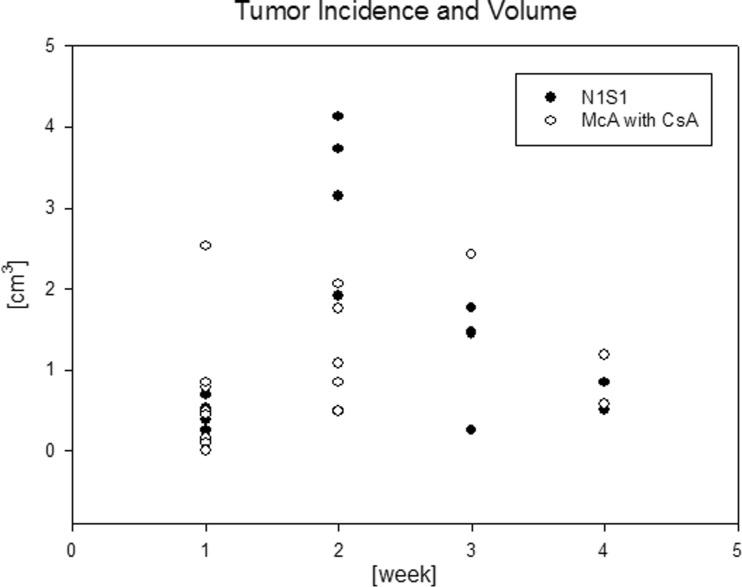

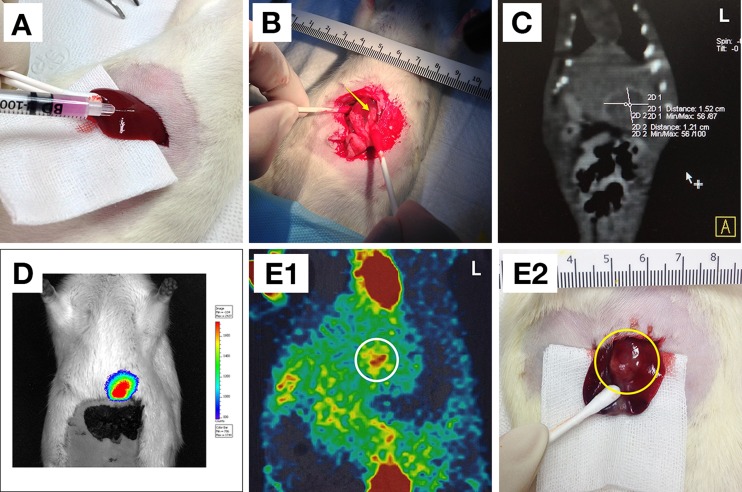

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the policies and procedures of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for animal treatment of Chonbuk National University. To design and assess the HCC orthotopic rat models (Sprague Dawley rat, n = 10), we started with the McA-RH7777 cell line, but most inoculated tumors spontaneously regressed (Fig. 1), similar to previously published findings by other researchers [29, 30]. The administration of CsA was considered as a method of pre-treatment. We achieved a significant tumor incidence with orthotopic HCC (Table 2, Fig. 2). We attempted to assess and identify the incidence, size changes, and tumor location with different types of imaging modalities: CT (Symbia TruePoint SPECT-CT, Siemens, Munich, Germany), PET/CT (FLEX Pre-clinical Platform, Gamma Medica-Ideas, Salem, USA) and BLI, as well as by surgical laparotomy (Fig. 3). Monitoring the tumor progression of HCC with CT, we were able to assess tumor dimension, tumor location, tumor progression, as well as anatomical information. The CT modality was the most helpful in the measurement of tumor dimensions because of its timesaving attributes. CT modality obviated the need for surgery, such as laparotomy. Using PET/CT imaging with 18F-FDG, we were also able to successfully observe the tumor location. We additionally identified the existence of HCC tumor by BLI imaging, using an in vivo imaging system (IVIS Spectrum; PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA). The HCC tumor can be detected by measuring luminescent intensity emitted from the inoculated HCC, if there is an expression of luciferase genes in the HCC cell lines. It provides a valuable means of monitoring invisible tumors, such as an orthotopic HCC.

Fig. 1.

CT images of HCC rat model. The regression of tumor was assessed by CT imaging and tumor size measured at follow-up day 18 (W: 14.60 cm, H: 16.64 cm) and day 25 (W: 8.79 cm, H: 13.39). The issue about HCC regression has been reported from any other laboratories in the world

Table 2.

Tumor incidence for the orthotopic HCC model. Two types of cell line and the immunosuppressant, cyclosphorin A (CsA), were used to establish the orthotopic HCC rat model. When using CsA, the tumor incidence of HCC shows a totally outstanding result

| Cell lines | CsA | Number of rats | Number of successes | Tumor incidence [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1S1 | Not used | 59 | 6 | 10.17 |

| McA-RH7777 | Not used | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Used | 10 | 10 | 100 |

Fig. 2.

The frequency and size of HCCs at weekly intervals in two rat model groups: N1S1 without CsA and McA-7777 with CsA

Fig. 3.

a The inoculation of an HCC cell line by subcapsular injection. b–e Four types of method to assess the tumor incidence of HCC at the 14th day postoperative day. b Laparotomy was performed by once to three times. The yellow colored arrow indicates a tumor. c CT was also performed to follow-up tumor incidence or size growth. d BLI of McA-7777 with a luciferase is easily able to confirm a tumor incidence. e 1 PET/CT with 18F-FDG provides valuable diagnostic information via the glycometabolism of the tumor with anatomical information in both preclinical and clinical trials. The white colored circle indicates a tumor as expected; 2 the yellow colored circle indicates where the tumor is indicated in 1

According to our experimental research, we believe that various bio-molecular imaging methods are the most valuable tools for detection and evaluation of different types of tumors in any pre-clinical and clinical trials.

Conclusions

Several experimental design methods of orthotopic HCC animal models have been reported. These models have been used to develop therapeutic methods and to evaluate tumor progression in preclinical and clinical trials in various laboratories. Furthermore, sophisticated bio-molecular imaging modalities—US, CT, MRI, PET/CT and BLI—have been developed to assess the orthotopic HCC models and have been applied for several decades. Thus, both the therapeutic interpretation and diagnostic results have generated valuable information with high accuracy, in preclinical as well as clinical studies.

The orthotopic HCC models induced by immunosuppressants have shown significantly high tumor incidence, thus facilitating well-designed research procedures. However, the biological relationship between tumor and immunosuppressants needs to be further considered, since it may not be affordable in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Radiation Technology R&D programs through the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant (NRFG) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012-M2A2A7014020, 2011-0028581).

Conflict of Interest

Tai Kyoung Lee, Kyung Sook Na, Jeonghun Kim and Hwan-Jeong Jeong declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the animal ethics committee in our hospital and performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Liver Cancer Estimated Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx. Accessed 13 Mar 2014.

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz J, Mazzolini G, Sangro B, Qian C, Prieto J. Gene Therapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig Dis. 2001;19:324–32. doi: 10.1159/000050699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SY, Hann HW. Hepatitis B related hepatocellular carcinoma. OA Hepatology. 2013;1(1):7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu C, Zhou W, Wang Y, Qiao L. Hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(2):216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson SC, Johnson DE, Harris MP, et al. p53 gene therapy in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1649–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma-cause, treatment and metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(4):445–54. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KI, Lee YJ, Lee TS, Song I, Cheon GJ, Lim SM, et al. In vitro radionuclide therapy and in vivo scintigraphic imaging of alpha-fetoprotein-producing hepatocellular carcinoma by targeted sodium iodide symporter gene expression. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;47:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13139-012-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quagliata L, Matter MS, Piscuoglio S, Arabi L, Ruiz C, Procino A, et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTTIP/HOXA13 expression is associated with disease progression and predicts outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):911–23. doi: 10.1002/hep.26740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tai WT, Shiau CW, Chen PJ, Chu PY, Huang HP, Liu CY, et al. Discovery of novel Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 agonists from sorafenib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):190–201. doi: 10.1002/hep.26640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng YF, Shi YH, Ding ZB, Ke AW, Gu CY, Hui B, et al. Autophagy inhibition suppresses pulmonary metastasis of HCC in mice via impairing anoikis resistance and colonization of HCC cells. Autophagy. 2013;9(12):2056–68. doi: 10.4161/auto.26398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huynh H, Ong R, Soo KC. Foretinib demonstrates anti-tumor activity and improves overall survival in preclinical models of hepatocellular carcinoma. Angiogenesis. 2012;15(1):59–70. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9243-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chae MJ, Lee ST, Kim JY, Woo GS, Jung WS, Chun KS, et al. Small animal PET imaging with [124I]FIAU for herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase gene expression in a hepatoma model. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;42(3):235–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin CY, Chen JH, Liang JA, Lin CC, Jeng LB, Kao CH. 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT for detecting extrahepatic metastases or recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(9):2417–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addley HC, Griffin N, Shaw AS, Mannelli L, Parker RA, Aitken S, et al. Accuracy of hepatocellular carcinoma detection on multidetector CT in a transplant liver population with explant liver correlation. Clin Radiol. 2011;66(4):349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma X, Liu Z, Yang X, Gao Q, Zhu S, Qin C, et al. Dual-modality monitoring of tumor response to cyclophosphamide therapy in mice with bioluminescence imaging and small-animal positron emission tomography. Mol Imaging. 2011;10(4):278–83. doi: 10.2310/7290.2010.00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson SM, Callstrom MR, Knudsen B, Anderson JL, Butters KA, Grande JP, et al. AS30D model of hepatocellular carcinoma: tumorigenicity and preliminary characterization by imaging, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(1):198–203. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz V, Tirado-Ledo L, Tiemann K, Raskopf E, Heinicke T, Ziske C, et al. Establishment of an orthotopic tumour model for hepatocellular carcinoma and non-invasive in vivo tumour imaging by high resolution ultrasound in mice. J Hepatol. 2004;40(5):787–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Tang ZY, Ye SL, Liu YK, Chen J, Xue Q, et al. Establishment of cell clones with different metastatic potential from the metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line MHCC97. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(5):630–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armengol C, Tarafa G, Boix L, Solé M, Queralt R, Costa D, et al. Orthotopic implantation of human hepatocellular carcinoma in mice: analysis of tumor progression and establishment of the BCLC-9 cell line. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(6):2150–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin HL, Lui WY, Liu TY, Chi CW. Reversal of Taxol resistance in hepatoma by cyclosporin A: involvement of the PI-3 kinase-AKT 1 pathway. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(6):973–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TK, Lau TC, Ng IO. Doxorubicin-induced apoptosis and chemosensitivity in hepatoma cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;49(1):78–86. doi: 10.1007/s00280-001-0376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao X, Hu JF, Daniels M, et al. A novel orthotopic tumor model to study growth factors and oncogenes in hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2719–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma SH, Chen GG, Yip J, Lai PB. Therapeutic effect of alpha-fetoprotein promoter-mediated tBid and chemotherapeutic agents on orthotopic liver tumor in mice. Gene Ther. 2010;17(7):905–12. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vongchan P, Kothan S, Wutti-In Y, Linhardt RJ. Inhibition of human tumor xenograft growth in nude mice by a novel monoclonal anti-HSPG isolated from human liver. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(12):4067–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandra PK, Kundu AK, Hazari S, Chandra S, Bao L, Ooms T, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication by intracellular delivery of multiple siRNAs by nanosomes. Mol Ther. 2012;20(9):1724–36. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29.Cho HR, Choi JW, Kim HC, Song YS, Kim GM, Son KR, et al. Sprague-Dawley rats bearing McA-RH7777 cells for study of hepatoma and transarterial chemoembolization. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(1):223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buijs M, Geschwind JF, Syed LH, Ganapathy-Kanniappan S, Kunjithapatham R, Wijlemans JW, et al. Spontaneous tumor regression in a syngeneic rat model of liver cancer: implications for survival studies. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(12):1685–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu SD, Ma YS, Fang Y, Liu LL, Fu D, Shen XZ. Role of the microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(3):218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HJ, Choi HJ, Yang HM, Kim YM, Lee J, Chio D, et al. Establishment of primary xenograft model from newly characterized patient extrauterine carcinosarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(9):1552–60. doi: 10.1097/01.IGC.0000434105.98035.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Luan W, Goz V, Burakoff SJ, Hiotis SP. Non-invasive in vivo imaging for liver tumour progression using an orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma model in immunocompetent mice. Liver Int. 2011;31(8):1200–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walters DM, Stokes JB, Adair SJ. Stelow EB. Lowrey BT, et al. Clinical, molecular and genetic validation of a murine orthotopic xenograft model of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using fresh human specimens. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Lu W, Melancon MP, Xiong C, Huang Q, Elliott A, Song S, et al. Effects of photoacoustic imaging and photothermal ablation therapy mediated by targeted hollow gold nanospheres in an orthotopic mouse xenograft model of glioma. Cancer Res. 2011;71(19):6116–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliva MR, Saini S. Liver cancer imaging: role of CT. US and PET. Cancer Imaging. 2004;4(Spec No A):S42-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cheung TT, Fan ST, Chan SC, Chok KS, Chu FS, Jenkins CR, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation: an effective bridging therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(20):3083–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wintermark M, Sesay M, Barbier E, Borbély K, Dillon WP, Eastwood JD, et al. Comparative overview of brain perfusion imaging techniques. J Neuroradiol. 2005;32(5):294–314. doi: 10.1016/S0150-9861(05)83159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarraf-Yazdi S, Mi J, Dewhirst MW, Clary BM. Use of in vivo bioluminescence imaging to predict hepatic tumor burden in mice. J Surg Res. 2004;120(2):249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng J, Xu L, Zhou H, Zhang W, Chen Z. Quantitative analysis of cell tracing by in vivo imaging system. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2010;30(4):541–5. doi: 10.1007/s11596-010-0465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pino-Lagos K, Michea P, Sauma D, Alba A, Morales J, Bono MR, et al. Cyclosporin A-treated dendritic cells may affect the outcome of organ transplantation by decreasing CD4 + CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. Biol Res. 2010;43(3):333–7. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602010000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogosheske JR, Fargen AD, DeFor TE, Warlick E, Arora M, Blazar BR, et al. Higher therapeutic CsA levels early post transplantation reduce risk of acute GVHD and improves survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(1):122–5. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamdy S, Haddadi A, Shayeganpour A, Alshamsan A, Montazeri Aliabadi H, Lavasanifar A. The immunosuppressive activity of polymeric micellar formulation of cyclosporine A: in vitro and in vivo studies. AAPS J. 2011;13(2):159–68. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9259-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammond-McKibben D, Lake P, Zhang J, Tart-Risher N, Hugo R, Weetall M. A high-capacity quantitative mouse model of drug-mediated immunosuppression based on rejection of an allogeneic subcutaneous tumor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297(3):1144–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van de Vrie W, Marquet RL, Eggermont AM. Cyclosporin A enhances locoregional metastasis of the CC531 rat colon tumour. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1997;123(1):21–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01212610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]