Abstract

Shallow-sea (5 m depth) hydrothermal venting off Milos Island provides an ideal opportunity to target transitions between igneous abiogenic sulfide inputs and biogenic sulfide production during microbial sulfate reduction. Seafloor vent features include large (>1 m2) white patches containing hydrothermal minerals (elemental sulfur and orange/yellow patches of arsenic-sulfides) and cells of sulfur oxidizing and reducing microorganisms. Sulfide-sensitive film deployed in the vent and non-vent sediments captured strong geochemical spatial patterns that varied from advective to diffusive sulfide transport from the subsurface. Despite clear visual evidence for the close association of vent organisms and hydrothermalism, the sulfur and oxygen isotope composition of pore fluids did not permit delineation of a biotic signal separate from an abiotic signal. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in the free gas had uniform δ34S values (2.5 ± 0.28‰, n = 4) that were nearly identical to pore water H2S (2.7 ± 0.36‰, n = 21). In pore water sulfate, there were no paired increases in δ34SSO4 and δ18OSO4 as expected of microbial sulfate reduction. Instead, pore water δ34SSO4 values decreased (from approximately 21‰ to 17‰) as temperature increased (up to 97.4°C) across each hydrothermal feature. We interpret the inverse relationship between temperature and δ34SSO4 as a mixing process between oxic seawater and 34S-depleted hydrothermal inputs that are oxidized during seawater entrainment. An isotope mass balance model suggests secondary sulfate from sulfide oxidation provides at least 15% of the bulk sulfate pool. Coincident with this trend in δ34SSO4, the oxygen isotope composition of sulfate tended to be 18O-enriched in low pH (<5), high temperature (>75°C) pore waters. The shift toward high δ18OSO4 is consistent with equilibrium isotope exchange under acidic and high temperature conditions. The source of H2S contained in hydrothermal fluids could not be determined with the present dataset; however, the end-member δ34S value of H2S discharged to the seafloor is consistent with equilibrium isotope exchange with subsurface anhydrite veins at a temperature of ~300°C. Any biological sulfur cycling within these hydrothermal systems is masked by abiotic chemical reactions driven by mixing between low-sulfate, H2S-rich hydrothermal fluids and oxic, sulfate-rich seawater.

Keywords: Palaeochori Bay, Milos Island, Shallow-sea hydrothermal vents, Phase separation, Sulfur isotopes, Sulfate oxygen isotopes, Anhydrite, Sulfide oxidation

Introduction

Sulfur is critical to the functioning of all living organisms, including energy transduction, enzyme catalysis, and protein synthesis [1]. The sulfur biogeochemical cycle, with its broad range in valence (−2 to +6), exhibits a complex interplay between biotic and abiotic processes in hydrothermal vent ecology. Perhaps the most important biological pathway for H2S production in sediment-hosted marine environments is microbial sulfate reduction coupled to organic matter mineralization [2],[3]. Abiotic sources of sulfur in seafloor hydrothermal systems include volcanic inputs (H2S and SO2) and seawater sulfate that has undergone thermochemical reduction, anhydrite precipitation, or water-rock interactions [4]–[6]. Hydrologic circulation of seawater through cracks and fissures of hot ocean crust results in a net removal of seawater sulfate through the formation of anhydrite (CaSO4) [7],[8]. Overall, the exchange between seawater and ocean crust results in significant sources (e.g. Ca and Fe) and sinks (e.g. Mg and S) of elements to the global oceans [8]–[10]. These elemental budgets are primarily derived from investigations of altered basalt in trenches and deep-sea hydrothermal vents in spreading crust (mid-ocean and back-arc spreading centers) [11].

Sulfur (δ34S) and oxygen (δ18O) isotopes have provided valuable insight into deep-sea hydrothermal processes. The isotopic composition of hydrothermal fluids depends on the relative contributions of different sulfur (or oxygen) sources, their isotopic composition, and any fractionation effect that may occur during rate-limiting chemical or biological reactions. Assuming a simple two end-member system, sulfur within the ocean crust (δ34S ≈ 0‰) [12]–[15] can be distinguished from seawater sulfate (δ34SSO4 = 21.1‰) [16]. However, multiple investigations have shown that the isotopic signature of igneous sulfur is not uniform and that it depends upon oxygen fugacity of the melt [15], extent of melting [17], and water-rock interaction during assent of hydrothermal fluids. Although the subsurface variability can be due to multiple abiotic reactions, direct measurements of xenoliths provides some constraint on the sulfur isotopic composition of the mantle (δ34S = −5 to 9‰) [17],[18], and compilations of vent fluids and seafloor sulfide minerals (δ34S = −1 to 14‰) as reviewed in [13] approximate these mantle values. In contrast to the slightly 34S-enriched igneous contributions, sulfur inputs that have cycled through microbial sulfate reduction are characteristically depleted in 34S (Δ34SSO4-H2S up to 66‰) [19],[20]. Such low δ34S values have been essential in recognizing microbial activity in the deep biosphere within altered marine crust [12]–[14],[21]. Likewise, low δ34S (<< 0‰) of hydrothermal seafloor deposits is diagnostic of biogenic H2S recycled into the crust during basin-scale subduction of marine sediments [22],[23].

The oxygen isotope composition of global seawater (δ18OH2O = 0‰) tends to become 18O-enriched during thermal alteration [24]. Isotopic exchange between sulfate oxygen (δ18OSO4 = 8.7‰) and water is exceptionally slow (107 years) at normal seawater conditions (temperature = 4°C and pH = 8) [25]; however, δ18OSO4 of residual sulfate increases during microbial sulfate reduction and equilibrium isotope exchange that proceeds through the sulfur intermediate species sulfite [26],[27]. These sulfur and oxygen end-members have been informative in differentiating the relative contributions of seawater and igneous sources to high temperature fluids.

While stable isotope investigations of deep-sea hydrothermal systems (>1600 m water depth) have garnered much attention [12]–[14],[21],[28],[29], their shallow-sea analogs have been largely overlooked [30]–[32]. Volcanic arcs often produce shallow-sea vent systems, and their geochemical cycles can differ demonstrably from those found in mid-ocean ridges. Compared to deep-sea hydrothermal systems, the shallow-sea varieties are generally cooler (<150°C), are under lower hydrostatic pressure (<21.1 bar by definition), and can be found within the photic zone near shore [33],[34]. Several processes can affect the overall composition of discharging hydrothermal fluids. Phase separation is a ubiquitous process in both deep- and shallow-sea hydrothermal systems [11],[35]–[38]. At the low pressures encountered in shallow-sea systems, phase separation often occurs below the critical point of seawater and can be equated to “subcritical” boiling [37],[39]. Thus, vent fluid salinities can vary drastically, from less than 6% up to 200% of normal seawater [11]. This process of phase separation is common to arc-systems and results in wide ranges of major element compositions and base metal precipitation [38],[39]. Water-rock interactions, magma composition and volatile inputs are also highly variable compared to the more uniform basaltic crust of deep-sea systems [38]. While hydrothermal venting can occur along higher permeability fracture zones in both deep- and shallow-sea environments [40], in the latter, these highly advective pathways can become diffusive by passage through overlying sediment [39]–[44]. Shallow-sea sediments have their own recirculation and fluid hydrodynamics that are influenced by wave action, currents, and sediment remobilization [45]–[47]. Furthermore, the discharging fluids in shallow-sea systems need not originate from seawater, but in many cases can be derived from meteoric fluids [39],[48],[49].

Each of these processes, as well as the complex interaction of reduced hydrothermal fluids with oxic seawater, can affect the isotopic composition of dissolved sulfate and H2S. One such critical process includes sulfide oxidation mediated by chemical or biological reactions. Much of the H2S generated during microbial sulfate reduction or submarine hydrothermal activity is ultimately oxidized back to sulfate through aerobic or anaerobic reactions; however, this eight electron transfer does not proceed in a single step [50]. A variety of intermediate sulfur species (including sulfite, thiosulfate, elemental sulfur, polythionates, and polysulfides) are produced during sulfide oxidation under oxic and anoxic conditions [51]. Once elemental sulfur is present, it can then react with sulfite and H2S to form thiosulfate and polysulfides [51]. Although transient and generally short lived, polysulfides and H2S are involved in pyrite formation, organic matter sulfurization, and trace metal immobilization [51],[52]. Sulfide oxidation pathways within shallow-sea hydrothermal vents include chemical oxidation and biologically mediated oxidation through chemolithotrophy and phototrophy. Sulfide oxidation with molecular oxygen (O2) is relatively slow in the absence of metal catalysts or microorganisms [50],[53] with the abiotic rate of that process in seawater primarily a function of oxygen concentration. The following rate law [54] can represent this reaction:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where, k is in kg of H2O mol−1 h−1[53],[55]. At conditions representative of shallow-sea hydrothermal venting e.g., [39], the half-life of H2S at pH 4, 100°C, 0.001 activity H2S at an ionic strength (I) of 0.7 would be approximately 8 days (207 hours). In part because the abiotic oxidation kinetics are slow, chemolithotrophic microorganisms can gain energy by catalyzing this process. Aerobic chemolithotrophs can increase the net sulfide oxidation rate by many orders of magnitude, depending on cell density [56].

Environments with biological activity in close proximity to hydrothermal inputs, such as those found in shallow-sea vents, might offer a unique opportunity to explore the relative contributions of biotic and abiotic reactions to local sulfur cycling. The geochemical sulfur transformations in these settings create environmental gradients suitable for microbial activity within marine hydrothermal systems, and the biological utilization imparts additional pathways of sulfur redox chemistry. Here we investigate the impact of shallow-sea hydrothermal activity on marine sulfur cycling as revealed in sulfur and oxygen isotopes of vent fluids in coastal waters of Milos Island, Greece, with the goal of determining whether biological isotopic signals can be detected and distinguished from hydrothermal abiotic reactions. A novel film method was used to document high-resolution (mm-scale) changes in H2S abundance in order to best approximate spatial scales relevant to microorganisms [57],[58]. This work further contributes to improved understanding of sulfur and oxygen isotope systematics in shallow-sea hydrothermal systems and associated interactions with the ocean, with important consequences for refining global biogeochemical budgets [59],[60] and for providing modern analogs for evolving chemistry of the ancient ocean [61],[62].

Site description

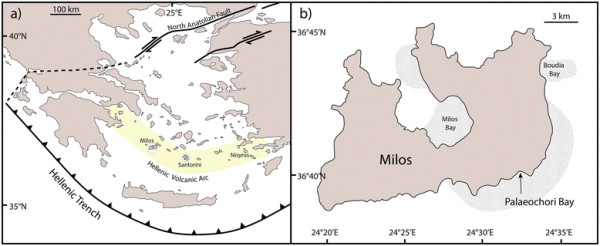

Milos is an island arc volcano located along the Hellenic Volcanic Arc in the Aegean Sea (Figure 1a). The arc system was formed by convergence between the African and the Aegean continental plates during the closure of the Tethys ocean [63]. Ocean crust subduction and crustal thinning of the continental margin results in magmas of intermediate to felsic composition (andesite, dacite, rhyolite) [64]. Since the last eruption ~90 kya, remnant heat from the dormant system drives hydrothermal circulation in many places on land and in the shallow sea, particularly near the southeastern part of the island (Figure 1b; shaded areas). Hydrothermal venting is manifested as extensive areas of free gas discharge and diffusively venting geothermal fluids along the shoreline to depths of at least 110 m [42],[65],[66] (Figure 1b). The interaction between reduced, H2S-rich, hot (up to 111°C), slightly acidic (pH 4–5) hydrothermal fluids and cooler, oxygen-rich, slightly alkaline seawater produces mineral precipitates inhabited by microbial communities on the seafloor that are visible from the shore (Figure 2a). The hydrothermal fluids are highly enriched in H2S (up to several millimolar) [39],[41],[42], and elemental sulfur and arsenic-sulfide are common precipitates [39]. The white fluffy coatings (Figure 2b) were approximately 1-cm thick and host chemolithotrophic sulfide oxidizing and sulfate reducing bacteria [41],[67]–[70]. Vent gases emitted in Palaeochori Bay consist predominantly of carbon dioxide (~95% CO2), but also contain high concentrations of H2S and other volatiles (e.g., CH4 and H2) [41]. The efflux of fluids charged with carbon dioxide and H2S likely support sulfide oxidizing bacteria that inhabit the white regions. However, there appears to be a dynamic sulfur cycle at the site, featuring both biotic and abiotic sulfur oxidation and reduction [67],[68],[70]–[72].

Figure 1.

Map of shallow sea hydrothermal vents. (a) The hydrothermally active islands of Milos, Santorini, and Nisyros are located along the Hellenic Volcanic Arc. (b) Samples were collected in 2011 from shallow (~5 m water depth) submarine hydrothermal sites in Palaeochori Bay. The shaded areas represent the areal extent of hydrothermal activity (34 km2) observed around Milos [73]. Figures modified from previous Milos studies [73],[74].

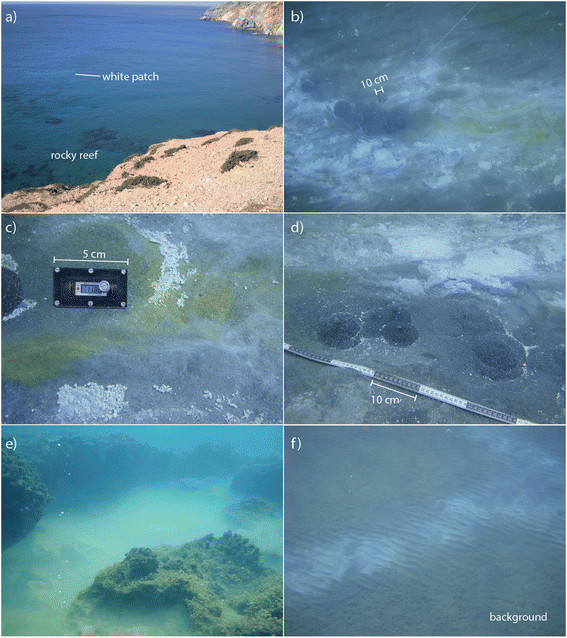

Figure 2.

Pictures of hydrothermal features in Palaeochori Bay. (a) White patches and a rocky reef as seen from cliffs overlooking the bay. (b) The physical appearance of the hydrothermal features was highly heterogeneous, ranging from patches of white to orange/yellow precipitates grading into non-pigmented background sediments. (c) The yellow and orange precipitates tended to form toward the center of the features where pore water temperatures were highest. (d) Gas flow from several vent mounds formed streams of bubbles in the water column. (e) Saline brine accumulated within a depression of a rocky reef. (f) Background sediments with no visible evidence for venting or microbial cover were used as control sites.

The seabed near our sampling area is composed of rocky reef within meters of the shoreline and sandy sediment throughout the bay (Figure 2a). The entire study area is above wave base (depth of ~ 5 m) and thus is often exposed to wind-driven mixing. The bottom topography includes wave ripples covered with white patches (Figure 2b), yellow and orange precipitates (Figure 2c), rounded mounds of dark, fluidized sand emitting free gas (Figure 2d), and a hyper-saline brine accumulated within the depression of a rocky reef (Figure 2e). The white patches and orange/yellow precipitates are much warmer (>40°C) than the surrounding sediments [39],[68],[75]. Thermal fluids often contained elevated concentrations of Na, Ca, K, Cl, SiO2, Fe, and Mn relative to mean seawater concentration [39],[42],[65],[66],[69] and were typically depleted in SO4 and Mg [39],[42],[66],[69]. However, recently a low-Cl fluid (depleted by as much as 66% relative to seawater) also depleted in Na, Mg, SO4, and Br, was sampled within a few meters of the high-Cl vents [39]. Brown (background) sediments outside of the hydrothermal features have temperatures and pore water chemistry that are similar to ambient seawater e.g., [39] (Figure 2f).

Methods

Fieldwork

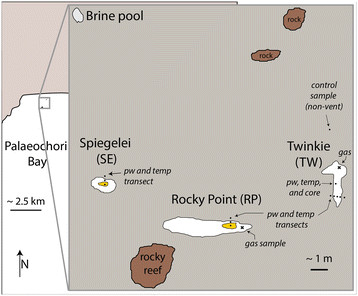

SCUBA divers collected samples (pore waters, water column and free gas) and conducted in situ temperature measurements in 2011 at study sites ‘Rocky Point’, ‘Spiegelei’, ‘Twinkie’ and the ‘Brine pool’ (Figure 3). White patches were observed within Rocky Point, Spiegelei, and Twinkie. Orange, interspersed with yellow, precipitates were found in the central areas (approximately 25 to 50 cm in diameter) of Rocky Point and Spiegelei. The patches at Twinkie were predominately white in color, with some small areas of yellow precipitate (approximately 1 cm in diameter) located toward the center of the site. Pore water sampling was conducted along transects that extended from the center of the hydrothermal vents into gray sediment (a distance of approximately 1 m) to provide environmental context between vent and adjacent sediment. Background samples were also collected from a control site located away from actively venting sediments (Figure 3; ‘control sample’). Discrete pore water samples were collected in 5 to 10-cm depth intervals to a maximum depth of 20 cm using a pipette tip attached to tygon tubing and a 60 ml syringe [39]. The first 20 ml were discarded to decrease potential seawater contamination during sampling. Seawater was collected from the bay surface near the shore and away from any apparent venting activity. A second seawater sample was collected from the bottom water overlying the Twinkie study site. A white patch area north of the transect at Twinkie was also cored with polycarbonate tubes that were sealed underwater. The pore water chemistry of the cored sediments was analyzed by voltammetry (described in 3.2 Analytical). Surface sediments were also collected from each site using 50 ml centrifuge tubes.

Figure 3.

Location map of the Brine pool, and the white patches of Twinkie (TW), Rocky Point (RP), and Spiegelei (SE). The center of RP and SE contained large areas of orange precipitate. Pore water samples and temperature measurements were taken along transects within each sampling site. Pore water, temperature and a sediment core were also collected north of the transect in TW. Free gas samples (×) were collected from RP and TW. A station north of TW was collected to provide a control sample from non-vent sediments.

Samples of free gas were collected from active vents through an inverted funnel placed over an area where free gas bubbles streamed through the seafloor sediments (Figure 3; ‘×’). Outflow from the funnel was collected in a syringe with luer lok fittings and sealed with a stopcock. Dissolved H2S in filtered pore waters (0.2 μm membrane filters) and free gas was precipitated as ZnS by addition of 3% zinc acetate (wt/v) within 1 hour after completion of the dive. Pore water temperatures were determined with a digital thermometer in an underwater housing.

Pore water pH was measured using a WTW pH meter and a MIC-D electrode with built-in temperature compensation, which had a precision of 0.1 pH units. Dissolved sulfate and chloride concentrations were determined by ion chromatography on a Dionex DX600 with a ED50 detector and KOH eluent gradient. Analytical precision of field and laboratory duplicates had a reproducibility of ±5%.

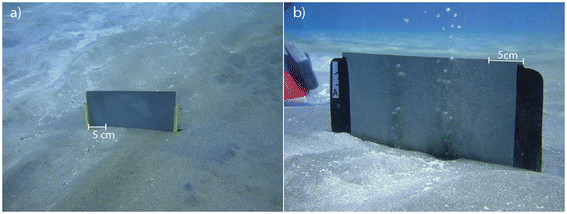

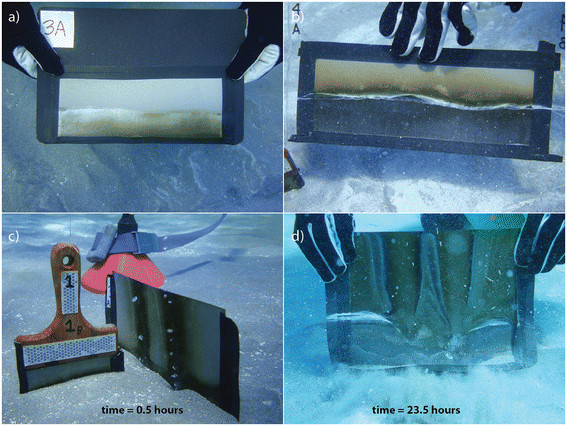

Silver halide-embedded photographic films (Ilford Delta 100) were deployed to precipitate dissolved H2S within white- and yellow-stained sediment, and background (non-vent) sediments (Figure 2b, c, d, f). Films were also deployed in diffusively venting (Figure 4a) and actively venting (Figure 4b) sediments. Dissolved H2S reacted with the silver in the film surface to form Ag2S. The degree of coloration is proportional to the mass of H2S that reacted with the film (Figure 5). Dissolved H2S that precipitated in the films represents a time-averaged H2S flux for sulfur isotope analysis. Films (4 x 5 inches or 8 x 10 inches) were deployed for at least 1 hour and up to 24 hours to ensure quantitative reaction of the silver in the resins with dissolved and free gas H2S. The films were stable within the environmental pH range of 4 to 8. Trial deployments revealed that the silver-containing resin separated from the acetate backing of the film when exposed to temperatures above 90°C. Noting this temperature effect, films were successfully used in sediment temperatures up to ~85°C.

Figure 4.

Films were deployed by SCUBA to capture free sulfide (a) dissolved in the pore waters and (b) venting from gas mounds.

Figure 5.

The film-method captured the highly variable sulfide flux across the hydrothermal sites. (a) The undulating surface of ripple marks and the position of the sediment water interface were retained on films. (b) White filamentous material indicates the position of the sediment and the sulfide-staining above the interface indicates sulfide diffusion directly into the bottom waters. (c) Gas plumes imprinted on a film placed near an active vent mound within 30 minutes and (d) after 23 hours.

Analytical

Dissolved H2S concentrations of syringe-sampled fluids were measured by voltammetry on a DLK-60 potentiostat (Analytical Instrument Systems) using a three electrode system consisting of a 100 μm Au-amalgam working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and Pt counter [76]. Voltammetric signals are produced when redox-active dissolved or nanoparticulate species interact with the surface of the Au-amalgam (Au-Hg alloy) working electrode. Electron flow, resulting from redox half-reactions occurring at specific potentials at the 100 μm Au-amalgam diameter working electrode surface, is registered as a current that is proportional to concentration [77]–[79]. Cyclic voltammetry was performed between −0.1 and −1.8 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 1000 mV s−1 with a 2 s conditioning step. Aqueous and nanoparticulate sulfur species that are electroactive at the Au-amalgam electrode surface of direct relevance to this study include HS−, H2S, S8, polysulfides, S2O32−, HSO3−, and S4O62−[80],[81]. Calibrations were performed in seawater collected on site utilizing the pilot ion method [82],[83]. Precision of the data using this technique is typically within 2-3% at these sulfide levels (<1000 μM); however, uncertainties tied to inter-electrode variability and compound analytical error associated with utilizing Mn2+ for calibration in the field can yield overall analytical uncertainties up to 10% [82],[83].

The δ34S values of the preserved sulfur compounds were measured with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Delta V Plus, at WUSTL) coupled under continuous flow to an elemental analyzer (Costech Analytical ECS 4010). Dissolved sulfate splits were precipitated as BaSO4 by addition of saturated barium chloride solution. H2S fixed as ZnS was reprecipitated as Ag2S by addition of silver nitrate solution. H2S trapped on photographic films were liberated by chromium reduction [84] and precipitated as Ag2S. Samples were mixed with vanadium pentoxide to ensure complete combustion. The oxygen isotope composition of sulfate (δ18OSO4) was measured by pyrolysis (Thermo TC/EA) and gas source mass spectrometry (Thermo Delta V Plus, at IUPUI). Graphite was added to each sample to promote consistent pyrolysis. The oxygen or sulfur isotope composition ( x E = 18O or 34S) was reported in per mil (‰) according to the equation:

| (3) |

where the isotopic ratio (R = 18O/16O or 34S/32S) of the sample is normalized to the isotopic ratio of the international standard for Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) or Vienna Canyon Diablo Troilite (VCDT), respectively. Oxygen isotope reference materials included IAEA-SO6 (δ18O = −11.0‰), NBS-127 (δ18O = 8.7‰), and IAEA-SO5 (δ18O = 12.0‰). Sulfur isotope values were calibrated against international reference materials IAEA-S3 (δ34S = −32.55‰), IAEA-S1 (δ34S = −0.3‰), and NBS-127 (δ34S = 21.1‰). For both oxygen and sulfur, linear regression was used to correct unknowns to the international reference values and to account for scale compression. Analytical precision for standards and replicate samples was ±0.2‰ (1σ) for oxygen and ±0.3‰ (1σ) for sulfur isotopes.

Sediments were analyzed for their mineral content by a combination of optical microscopy, X-ray Diffraction (XRD), and Raman microscopy. Thin sections of 3 representative areas where prepared by Vancouver Petrographics and analyzed together with grain mounts using an Olympus BX-53 microscope, a DeltaNu Rockhound portable Raman spectrometer with microscope attachment, and a Siemens D5000 XRD. Surface samples from background, white and yellow sediments were analyzed for total organic carbon (TOC) concentration. The sediments were decarbonated with 1 N HCl, rinsed three times with deionized water, and dried. Organic carbon content was measured on an elemental analyzer (Costech Analytical ECS 4010).

Results

The films method captured the spatial and temporal distribution of H2S within the upper few cm of sediment (Figures 4 and 5). Sedimentary structures, such as crests and troughs of wave ripples, as well as the position of the sediment-water interface were preserved on the film (Figure 5a). Film images also retained evidence for H2S efflux from the pore waters into the bottom water (Figure 5b) and the extent of the hydrothermal plume (Figures 5c and d). These transient and highly dynamic features of surficial venting preserved by the films are not readily sampled by static pore water extractions (e.g., rhizons, squeezing, or centrifugation) or by water column collections (e.g., Niskin or in situ pumping).

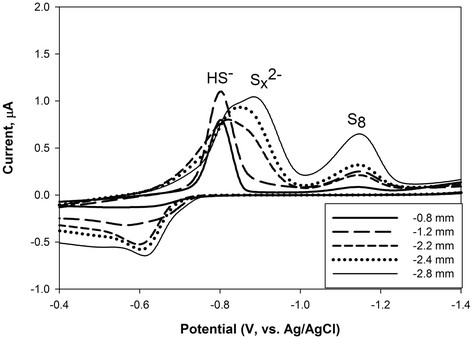

Voltammetric analysis of pore water sulfur speciation showed significant influence of precipitated elemental sulfur on the dissolved sulfur speciation present. Voltammetric scans (Figure 6) through a few millimeters of the upper portion of the core collected from Twinkie indicate the presence of micromolar levels of polysulfides when electroactive elemental sulfur is present. In contrast, there is no measurable polysulfide when voltammetric scans indicate low levels of elemental sulfur. This association with elemental sulfur, H2S, and polysulfide were observed in both core samples and in the syringe-sampled pore water. Based on equilibrium thermodynamics [85], this association, summarized by the reaction:

| (4) |

Figure 6.

Representative voltammetric scans from pore waters through a core collected from Twinkie, showing sulfide-dominated conditions and conditions with higher elemental sulfur corresponding to higher levels of polysulfide. Sulfide sourced from thermal fluids oxidizes to elemental sulfur, additional sulfide then reacts with this elemental sulfur to form polysulfide, a key part of sulfur intermediate chemistry influencing overall sulfur cycling in this system.

should yield a relatively low level of polysulfide (S n 2-) at pH between 4 and 8 (the range of observed pH in the system). Calculated total polysulfide levels [85] would be 55 nM at pH 4 and 20 μM at pH 8. However, our scans indicate a much more significant yield (at the pH for the scans in Figure 6 one would expect sub-micromolar total polysulfide concentrations, but the signal is a magnitude closer to one hundred micromolar polysulfide concentration). Samples without measureable elemental sulfur did not indicate the presence of measureable polysulfide. The observation of polysulfide, at concentrations higher than calculated equilibrium values, suggests the polysulfide levels seen in these core pore waters may be affected by other reactions than simply reaction (4).

Temperature and chemical compositions (including isotope values) of seawater, brine, and free gas are given in Table 1. Temperatures were elevated in the brine pool (46.8°C) and the free gas (>75°C at sites of venting) compared to seawater (22.1°C). The brine pool had high chloride concentrations (911.7 mM) and low sulfate (19.9 mM) relative to local seawater ([Cl] = 620.3 mM; [SO4] = 32.5 mM). The isotopic composition of surface seawater in Palaeochori Bay was δ34SSO4 = 21.2‰ and δ18OSO4 = 9.0‰. The δ34SH2S value of free gas from Twinkie and Rocky Point showed little variability (δ34SH2S = 2.5 ± 0.28‰, n = 4) (Table 1). Free gas H2S samples were not collected from the Spiegelei site.

Table 1.

Fluid and free gas chemical data

| Depth (cm) | pH | Temp. (°C) | Cl (mM) | SO 4 (mM) | H 2 S(μM) | δ 34 S SO4 (‰) | δ 18 O SO4 (‰) | δ 34 S H2S (‰) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Seawater |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Near shore, surface water |

- |

7.91 |

22.1 |

620 |

32.5 |

- |

21.2 |

9.0 |

0.0 |

| Twinkie site, bottom water |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

21.8 |

9.1 |

- |

|

Brine pool |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Brine pool west of beach |

- |

6.30 |

46.8 |

912 |

19.4 |

0.0 |

19.9 |

9.0 |

- |

|

Free gas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vent area, Twinkie site |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2.7 |

| |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2.1 |

| |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2.8 |

| Rocky Point |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2.4 |

|

Pore water |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rocky Point (RP) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Orange center |

10 |

4.38 |

88.6 |

929 |

8.7 |

92.0 |

- |

- |

- |

| |

20 |

4.02 |

92.5 |

890 |

7.9 |

109.0 |

- |

- |

- |

| White area |

10 |

5.32 |

67.9 |

745 |

20.8 |

257.0 |

21.2 |

- |

2.7 |

| |

20 |

5.33 |

79.4 |

731 |

20.8 |

246.0 |

21.9 |

- |

2.9 |

| White area |

10 |

5.19 |

61.3 |

718 |

25.5 |

198.0 |

20.2 |

- |

2.6 |

| |

20 |

5.21 |

68.0 |

734 |

25.9 |

186.0 |

20.7 |

- |

2.7 |

| Orange/Yellow area |

5 |

4.13 |

87.5 |

944 |

8.3 |

24.0 |

17.3 |

9.0 |

- |

| |

15 |

4.12 |

97.4 |

952 |

8.8 |

18.0 |

17.6 |

9.1 |

- |

|

Spiegelei (SE) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Orange/Yellow center |

5 |

4.94 |

79.6 |

960 |

22.0 |

9.0 |

18.2 |

9.4 |

2.9 |

| |

15 |

4.29 |

90.4 |

937 |

17.3 |

81.0 |

17.9 |

9.6 |

2.0 |

| White outer area |

5 |

5.21 |

76.5 |

884 |

17.6 |

9.0 |

20.1 |

9.3 |

1.9 |

| |

15 |

5.31 |

83.3 |

871 |

17.2 |

34.0 |

20.5 |

9.5 |

2.7 |

| Gray fringe |

5 |

5.72 |

28.3 |

788 |

21.6 |

0.0 |

21.0 |

9.7 |

- |

| |

15 |

5.73 |

41.4 |

796 |

21.9 |

0.0 |

21.3 |

9.7 |

- |

|

Twinkie (TW), west side of transect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Yellow/White center |

5 |

5.34 |

52.8 |

561 |

27.5 |

253.0 |

21.3 |

8.7 |

2.2 |

| |

10 |

- |

64.3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

15 |

5.42 |

69.6 |

563 |

29.9 |

286.0 |

20.4 |

8.9 |

- |

| |

20 |

- |

71.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| White area near edge |

5 |

5.26 |

42.6 |

620 |

31.7 |

231.0 |

21.7 |

8.8 |

2.3 |

| |

10 |

- |

51.7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

15 |

5.29 |

58.4 |

639 |

32.9 |

227.0 |

21.4 |

8.8 |

2.7 |

| |

20 |

- |

62.7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Gray area near edge |

5 |

5.24 |

33.5 |

633 |

35.3 |

247.0 |

21.6 |

9.1 |

3.3 |

| |

10 |

- |

39.9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| |

15 |

5.20 |

45.5 |

630 |

32.7 |

239.0 |

21.6 |

9.1 |

3.2 |

| |

20 |

- |

49.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Twinkie (TW), east side of transect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Yellow/White center |

5 |

5.22 |

48.1 |

586 |

29.5 |

95.0 |

21.3 |

8.9 |

2.8 |

| |

15 |

5.18 |

67.8 |

583 |

29.3 |

129.0 |

21.3 |

8.9 |

2.8 |

| White area near edge |

5 |

5.22 |

40.3 |

604 |

30.6 |

82.0 |

21.6 |

8.2 |

2.6 |

| |

15 |

5.22 |

60.0 |

613 |

31.2 |

134.0 |

21.5 |

8.8 |

3.0 |

| Gray area near edge |

5 |

5.22 |

30.7 |

628 |

32.5 |

114.0 |

21.0 |

8.8 |

3.1 |

| |

15 |

5.21 |

46.7 |

634 |

33.2 |

127.0 |

21.6 |

9.0 |

2.6 |

|

Twinkie (TW), north of transect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| White area |

5 |

4.98 |

42.3 |

544 |

26.5 |

606.0 |

21.1 |

8.6 |

2.6 |

| |

15 |

4.98 |

60.5 |

529 |

26.2 |

992.0 |

21.5 |

8.6 |

2.5 |

|

Control (north of TW) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Background mud |

5 |

7.45 |

22.1 |

638 |

32.8 |

6.0 |

21.2 |

8.6 |

- |

| 15 | 7.36 | 23.0 | 640 | 33.0 | 42.0 | 21.0 | 8.5 | - | |

“-” indicates either no data or not applicable.

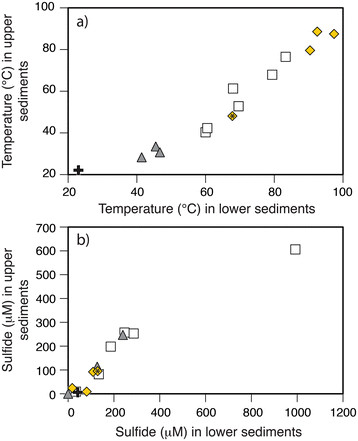

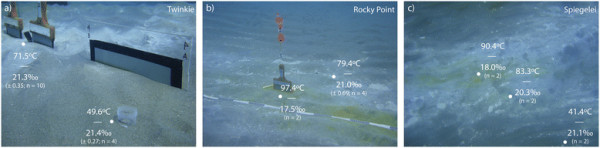

Pore waters (5–20 cm depth) exhibited a broad range in physical properties and chemistry (Table 1). The hydrothermal sites were moderately acidic (pH 4.0-5.7) and those from background sediments were circumneutral (pH ~ 7.4). Temperature profiles within the hydrothermal sites increased linearly with depth (Figure 7a). The temperatures in the upper 15 cm of background sediments were 22.1 to 23.0°C, and those of the pore waters in white patches were much higher (61.1 ± 13.6°C, n = 14). The temperatures of the yellow precipitate in Twinkie (48.1 to 67.8°C) were similar to the ranges observed in all white patches studied. In contrast, the highest temperatures were measured in orange precipitates of Rocky Point and Spiegelei, which ranged from 79.6 to 97.4°C. Temperatures of gray sediments collected along the margin of the vent areas plot along a gradient between vent influenced sediments (white and orange/yellow) and non-vent sediments (background) (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Changes in temperature and sulfide with depth in background and hydrothermal sediments. Relative to background sediment distal from venting (+), the (a) temperature increases with depth and toward the center of the vent features from gray sediments fringing the hydrothermal sites (▲), to the white patches (□) and orange/yellow precipitates (◆). The precipitates in Rocky Point and Spiegelei were both orange and those in Twinkie (symbol marked with ‘*’) were yellow in color. (b) Dissolved H2S concentrations also increase with depth in the gray and white sediments but are lowest in the yellow areas. Paired temperature and sulfide measurements in Twinkie and Spiegelei were made at 5 cm (the upper sediments) and 15 cm (lower sediments). Data from Rocky Point were measured at sediment depths of 10 cm and 20 cm.

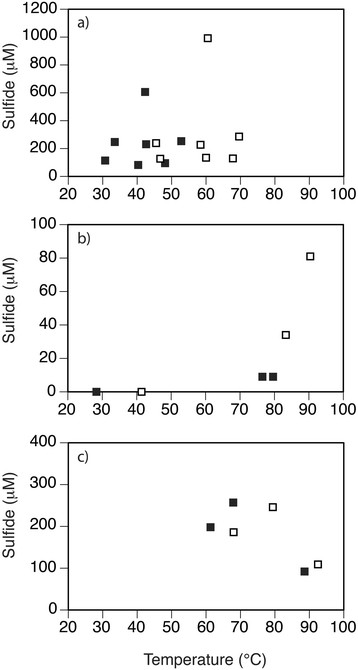

H2S concentrations were higher in areas of seafloor covered in white patches ([H2S]max = 992 μM) than either in gray sediments ([H2S]max = 247 μM), orange/yellow precipitates ([H2S]max = 129 μM), or background (non-vent) sediments ([H2S]max = 42 μM) (Figure 7b). The paired H2S and temperature data generally increased with depth in Twinkie and Spiegelei (Figures 8a and b). Although there are fewer paired measurements of H2S concentrations (S) and temperature (T) in Rocky Point, the S/T relationship decreases within the orange sediments (Figure 8c).

Figure 8.

Sulfide (S) and temperature (T) relationships observed in hydrothermal sites (a) Twinkie, (b) Spiegelei, and (c) Rocky Point. S/T measurements were made at 5 cm (closed symbols) and 15 cm (open symbols) sediment depth in (a) Twinkie and (b) Spiegelei, and at 10 cm (closed symbols) and 20 cm (open symbols) in (c) Rocky Point.

Pore water chloride concentrations in control sediments (~639 mM) were similar to those of ambient seawater (620.3 mM) (Table 1). Chloride levels in Twinkie pore waters (529.3 to 639.2 mM) were less than or equal to that of seawater, and those at Rocky Point and Spiegelei were elevated (731.2 to 959.5 mM), similar to the nearshore brine pool (911.7 mM). In contrast, sulfate concentrations at Rocky Point and Spiegelei (8.7 mM to 25.9 mM) were considerably lower than in seawater, whereas those at Twinkie (26.2 to 35.3 mM) were slightly lower to slightly above local seawater (32.5 mM).

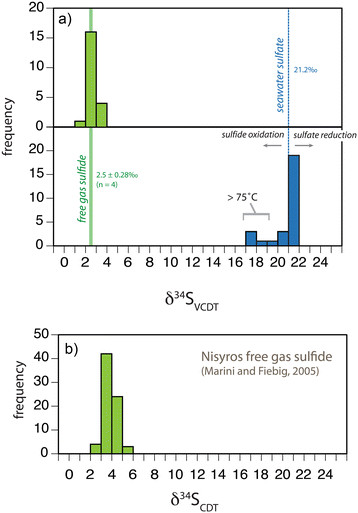

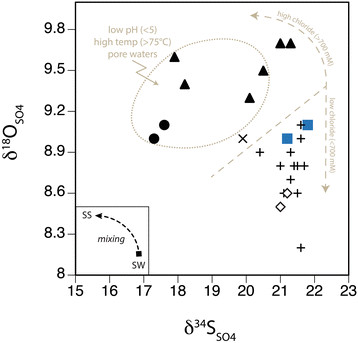

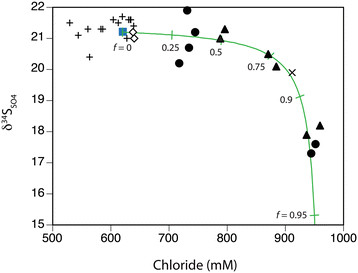

The pore water isotope signatures appear to be overprinted by abiotic chemical reactions. The δ34S increase in residual sulfate and associated low δ34S in in situ H2S production expected for microbial sulfate reduction was not observed in pore waters collected in this study. The isotopic composition of pore water H2S was constant (δ34SH2S = 2.7 ± 0.4‰, n = 21) across all sites and similar to that in vent gas (2.5‰) (Figure 9a). The δ34SSO4 that was identical to seawater was measured in pore waters sampled from background sediment and from Twinkie (Figure 9a). The exception was a lower δ34SSO4 value (20.4‰) of a high temperature sample (69.6°C) from Twinkie (Table 1). Pore waters in higher temperature sediments (>75°C) all decreased in δ34SSO4 (Figure 9a), which is a trend inconsistent with microbial sulfate reduction. When viewed spatially, the maximum temperatures were observed toward the center of each hydrothermal site (Figure 10). Although there is little variation in Twinkie δ34SSO4 (Figure 10a), Rocky Point and Spiegelei exhibited a pronounced decrease in δ34SSO4 as temperatures increased (Figures 10b and c). The lowest δ34SSO4 values (17.3‰ and 17.6‰) within these sites were observed at temperatures above 75°C in the orange zone of Rocky Point. A cross-plot of temperature and δ34SSO4 further demonstrates the overall trend of low δ34S values at high temperatures (Figure 11a). These high temperature, low δ34SSO4, pore waters also had the highest δ18OSO4 values (~9.5‰) (Figure 12). The more acidic (pH <5), warmer (>75°C), and more chloride-rich (>700 mM) pore waters of both Rocky Point and Spiegelei were 18O-enriched relative to ambient seawater sulfate (δ18OSO4 = 9.0‰). In contrast, pore waters in Twinkie and background sediments tended to have lower chloride concentrations (<700 mM) and lower δ18OSO4. Chloride concentrations appear to have a more direct relationship with δ34SSO4, that decreases as chloride increases (Figure 13). Pore water freshening (chloride concentrations less than seawater) does not appear to influence the δ34SSO4 in Twinkie (Figure 13; ‘+’).

Figure 9.

Sulfur isotope compositions of pore fluids and free gas samples. (a) Frequency distribution of δ34S values for sulfide (green) and sulfate (blue) collected from Palaeochori Bay, Milos (this study). The vertical solid line is the average of free gas sulfide in Palaeochori Bay (δ34S = 2.5‰) and the width of the line is the standard deviation of all measurements (±0.28‰, n = 4). The dashed vertical line represents seawater sulfate (δ34S = 21.2‰). (b) Frequency distribution of free gas sulfide δ34S at Nisyros Island [30]. Note, the δ34S values for this study (a) were normalized to VCDT and the literature values (b) were referenced to CDT.

Figure 10.

Maximum temperatures and average pore water δ 34 S SO4 for discrete samples collected 5 to 20 cm below the sediment water interface at hydrothermal sites (a) Twinkie, (b) Rocky Point, and (c) Spiegelei. The color of the surficial sediments varied from orange/yellow, white, and gray. δ34SSO4 decreased as temperatures increased toward the center of each feature.

Figure 11.

Relationship between pore water δ 34 S SO4 and temperature. (a) δ34SSO4 decreases with increasing temperature across the hydrothermal sites Twinkie (+), Rocky Point (●), and Spiegelei (▲), relative to the Brine pool (×), background sediments (◇), and surface seawater sulfate (sw; ■). (b) A mass balance model suggests an increasing fraction of secondary sulfate (f SS ) in sites with elevated temperatures.

Figure 12.

δ 18 O SO4 and δ 34 S SO4 of pore water in the hydrothermal sites Twinkie (+), Rocky Point (●), and Spiegelei (▲), relative to the Brine pool (×), background sediments (◇), and seawater (■). The inset illustrates the potential mixing trajectory between seawater sulfate (sw) and secondary sulfate (ss).

Figure 13.

δ 34 S SO4 values exhibit an inverse relationship with chloride concentrations. A conservative mixing model demonstrates elevated contributions of high-Cl fluid in Rocky Point (●), Spiegelei (▲), and the Brine pool (×), relative to Twinkie (+), background sediments (◇), and surface seawater (■).

The sediments collected from each site were screened by microscopy and for their element compositions. Polarized light microscopy (PLM) analyses of thin sections from three separate areas (white sediment, yellow sediment, and background (non-vent) sediments) indicate very similar mineralogical compositions with minor amounts of elemental sulfur as individual grains and as part of a coating. XRD analysis and thin section PLM indicates a predominance of quartz, with modal percentages via each technique estimated at over 90%, with minor clay and feldspar content but no calcite; this is in contrast to a study on sands in a different part of Milos that contained significantly more calcite, clay, and chlorite with much lower quartz content [86]. PLM analysis measured observable elemental sulfur particles of several microns in size, but in quantities <1%. Yellow and white coloration of the grains visible in stereomicroscope images is not visible in thin section, suggesting a very thin coating or reaction of these coatings with the epoxy during sample preparation. Raman spectroscopy of selected grains yields a weak signal for elemental sulfur (normally a strong Raman scatterer), suggesting the visible thin coating of material is at least partly elemental sulfur. The organic carbon concentrations in background, white and yellow sediments were very low (TOC = 0.04 - 0.08%).

Discussion

Geochemical variability

We observed chemical and isotopic variability that spanned broad spatial scales. At the scale of the geologic feature of the Hellenic Volcanic Arc (Figure 1a), the δ34S values of free gas H2S collected from Palaeochori Bay were highly uniform (2.5 ± 0.28‰, n = 4) and similar to fumorolic H2S (3.7 ± 0.6‰, n = 73) from Nisyros Island, >300 km away [30]. Consistency between volcanogenic δ34SH2S (Figure 9) from these two islands implies a regional control of H2S delivery.

At the local scale, chemical variability at vent sites in Palaelochori Bay is best explained by mixing. This is evidenced by changes in seafloor temperature that spanned from that of ambient seawater (22.1°C) to that of hydrothermal inputs (97.4°C). Temperature is often used as a proxy for evaluating the extent to which a hydrothermal fluid mixed with overlying seawater, and the shallow temperature gradients at Spiegelei, Rocky Point and Twinkie imply focused fluid flow at the center of the hydrothermal features (Figure 10). The concentric zonation observed at Rocky Point and Speigelei suggests that seafloor coloration is qualitatively linked to seafloor temperature and associated mineralization, ranging from orange (high temperatures) to white (intermediate temperatures) and gray (lower temperatures) (Figure 7a). The orange precipitates were only found in the warmest regions (>70°C) of the hydrothermal features surveyed in our study area. Small (~1 cm diameter) patches of yellow precipitates interspersed in the white mat were a more common precipitate. The yellow surface manifestations of fluid flow exhibited temperatures that were similar to those measured in the white patches. H2S concentrations however, had more direct relationship to temperature (Figure 7). For example, the H2S concentrations (up to 250 μM) of the low temperature (average of 36°C) gray sediments that surround the hydrothermal features are low compared to actively venting seafloor. The white patches are warmer (average of 61°C) and feature correspondingly higher pore water H2S concentrations (up to 990 μM). The central orange/yellow regions have the highest hydrothermal throughput (average 82°C), but H2S concentrations (up to 130 μΜ) appear to be buffered by removal during chemical oxidation to elemental sulfur and amorphous arsenic sulfides [39]. The accumulation of elemental sulfur within the highest temperature regions is consistently observed at the Palaeochori hydrothermal sites. The lack of prominent orange patches at the lower temperature Twinkie site is also consistent with this observation and with previous studies [39],[68],[73],[75],[87]. Temperature differences between these sites are thus a key constraint on the patterns of surficial geochemistry as expressed by seafloor coloration.

Intra-site variation in geochemistry occurs on two different scales; one controlled by the intrinsic heterogeneities of the sediment and another by hydrothermal convection. The film deployments revealed highly dynamic fluid exchange patterns between sulfidic fluids (brown or black stained film) and overlying seawater (gray, unreacted film) (Figure 5). H2S exposure on films placed in low temperature sediments with no visible evidence of gas flow (e.g., lack of bubble streams) typically exhibited a gradient of darker staining at the bottom of the film that faded toward the sediment water interface (Figure 5a). These films had a stippled pattern possibly caused by reaction with sulfidic fluids traveling between grain spaces, or the sediment grains themselves may create nucleation points for H2S precipitation. In either case, the stippled pattern captures the diffusive transport and mineral grain interactions within low-flow sites. Seafloor ripple marks and the position of the sediment interface are clearly imprinted on these films. In higher temperature white sediments characterized by advective flow, the films were completely darkened (Figure 5b). In one deployment, white filaments bound to the surface of the film, preserving the location of the sediment-water-interface and clearly demonstrating the efflux of H2S from the sediments into the overlying bottom waters (note position of white layer in Figure 5b). Regardless of the sediment composition, advective flux completely overwhelmed any localized differences in flow path or mineralogy (e.g., by wave actions, currents, and sediment remobilization). Similar patterns were observed within actively venting sites. Film deployed within a bubble stream reacted quickly (within 30 minutes) (Figure 5c) and retained the pattern of channelized flow from the sediment into the bottom water (Figure 5d). The films captured the flux of H2S into the overlying water column at a temporal and spatial resolution that improves upon traditional water sampling methods (pumping or syringe sampling).

Transient fluid flux and sediment heterogeneity are well characterized using the film method. In this study, all H2S had a uniform sulfur isotope composition (compare free gas and pore water H2S, Figure 9a). Although the H2S measured here is isotopically homogenous, exposure patterns suggest the film-capture method is an ideal technique for sampling across chemical and biological gradients.

Stable isotopes: biogenic vs. abiogenic signatures

The large white patches formed by chemical precipitation of H2S-rich and silica-rich hydrothermal fluids at the seafloor host an active microbial community predominated by chemolithotrophic sulfide oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Thiomicrospira spp., Thiobacillus hydrothermalis, Achromatium volutans) and thermophilic sulfate reducing bacteria (e.g., Desulfacinum spp) [41],[67]–[70],[72],[73],[87]. Sulfur isotope effects during chemical and biological sulfide oxidation are small (±5‰) [88]–[90] relative to the large isotopic offsets observed during microbial sulfate reduction (up to 66‰) [19],[20]. The process of biological sulfate reduction preferentially produces 34S-depleted H2S and residual sulfate enriched in 34S. Sulfur isotopic fractionation between seawater sulfate and product H2S depends on intracellular sulfur transformations during sulfate reduction [91], sulfate reduction rates [20], type of organic substrate [92], microbial community [93], sulfate supply [94], and possibly reoxidation reactions through sulfur disproportionation [95]. Although δ34S fractionations between sulfate and H2S can be either large (associated with sulfate reduction) or small (associated with sulfide oxidation), δ18O fractionations during oxidative and reductive sulfur cycling can both be substantial. Oxygen isotope exchange between intracellular sulfite and water during microbial sulfate reduction produces residual sulfate with high δ18OSO4[26]. Abiotic sulfide oxidation likewise produces a product sulfate with oxygen that is 18O-enriched relative to water or molecular oxygen [27].

Although there is an active community of sulfur oxidizing and reducing bacteria present at the vents, there is no isotope evidence in the bulk geochemical signatures that detects these microbial processes. Microbial sulfate reduction in the sediments would result in a downcore decrease in sulfate concentrations and an associated increase in δ34S and δ18O of the residual pore water sulfate. No such gradients in pore water sulfate concentration or isotope compositions were present in the upper 20 cm of the sediments. Furthermore, none of the H2S extracted from pore water or free gas exhibited the characteristically low δ34SH2S values consistent with microbially mediated sulfate reduction (Figure 9). There is also no clear isotopic evidence for sulfur utilization by sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. Previous studies of Milos microbial ecology would suggest that lower temperature white patches would be the most likely areas for an active microbial vent community. Yet, isotope effects (low δ34SSO4) were only observed within the hottest regions of the vents, not in Twinkie, which is a large white patch that hosts chemolithotrophic bacteria.

The lack of an obvious isotope signature for biotic sulfur cycling within vent and non-vent sediments suggests that in situ H2S production by microbial sulfate reduction is a minor process relative to the advective (abiotic) H2S flux, and that mixing with ambient seawater occurs at a rate sufficient to mask any signal from microbial sulfide oxidation. These results are surprising given that detailed microbial studies indicate the Milos vents are habitat to an active microbial community of sulfate reducers. Genetic sequences (16S rRNA) and abundance data (MPN) demonstrate that thermophilic sulfate reducers of the genus Desulfacinum are present within Milos vents [67],[68],[72]. Controlled experiments of natural microbial populations indicate that extant sulfate reducers are well-adapted to low pH and high pCO2 conditions of these hydrothermal systems [71]. In that same study, sulfate reduction rate measurements were determined ex situ in the laboratory and thus represent the potential rates of microbial sulfate reduction. Based on these experiments, the potential sulfate reduction rates in background sediments were higher than rates achieved in vent sediments [71]. Although the capacity for sulfate reduction is clearly demonstrated, the relative activity of reducers in situ may be limited by carbon availability. Previous studies of seagrass beds adjacent to white mats in Palaeochori Bay report high total organic carbon concentrations (0.2 - 3.2%) [73],[87], and sulfate reduction rates (up to 76 μmol SO4 dm−3 d−1) [73] that are similar to those observed at Guaymas Basin and Vulcano Island [33]. In contrast, the vent and non-vent sediments investigated in this study had low organic carbon content (0.04 - 0.08%) and likely low sulfate reduction rates. Furthermore, the films deployed in background sediments showed no visible evidence for reaction with pore water H2S.

The relatively low organic carbon content in the sandy sediments of the background and vent sites potentially minimizes biogenic H2S generation by microbial sulfate reduction in a setting where abiotic H2S appears to predominate. Admittedly, bulk isotope sampling may overlook biological utilization of sulfur within microfabrics or textures at the micron scale. For example, ion microprobe analysis of sulfide minerals (AVS, pyrite, and marcasite) in altered basalt of the West Pacific revealed low δ34S characteristic of sulfate reduction and isotopic variability in excess of 30‰ relative to bulk analysis [14]. Such microbial hotspots e.g., [57] are likely present in Palaeochori vents and will be a subject of subsequent studies. Overall, the bulk isotope observations are consistent with carbon and sulfur isotope results reported for the hydrothermally active island of Nisyros. The carbon isotope composition of fumarolic CO2 sampled from Nisyros falls on a mixing line between limestone and mid-ocean ridge basalt [96] and the δ34S value of free gas H2S reflects sulfur derived from a rhyodacite magma [31]. In many locations, Aegean sediments containing organic matter and biogenic H2S that would otherwise impart low δ13C and low δ34S to the subducted lithosphere are thus a minor contribution relative to the flux of abiotic carbon and sulfur sources recycled along the Hellenic Volcanic Arc.

Although biogenic H2S contributions are obscured by advection of hydrothermal H2S, the sulfur isotope variability observed in sulfate is influenced by hydrothermal input. The majority of pore water δ34SSO4 were consistent with Palaeochori seawater sulfate (21.2‰; Table 1), but those δ34S values that did deviate from normal seawater decreased at higher temperatures (>75°C) (Figure 9). Pore water data show a clear decrease in δ34SSO4 toward the centers of both Rocky Point and Spiegelei (Figures 10b and c). In contrast, δ34SSO4 values remain constant in the lower temperature site of Twinkie (Figure 10a). This pattern of low δ34SSO4 at high temperature suggests that seawater entrained by convective circulation oxidized H2S issued from the vents. Sulfide oxidation with molecular oxygen produces a sulfur isotope fractionation of −5.2‰ [88]. Assuming the hydrothermal H2S input is large relative to the mass of biogenic H2S, chemical oxidation of free gas H2S (2.5‰; Table 1) would produce a sulfate (referred herein as secondary sulfate) δ34S value of −2.7‰. A two-component mixing model,

| (5) |

can then be used to estimate the relative contribution of secondary sulfate (fss), assuming the δ34S value of sulfate within the pore water (δpw) is a mixture of oxic seawater (δsw = 21.2‰; Table 1) and sulfate formed from oxidized free gas H2S (δgas = −2.7‰). Isotopic mass balance suggests that approximately 15% (fss = 0.16) of pore water sulfate within the high temperature sites at Spiegelei and Rocky Point is derived from advected H2S that was oxidized by seawater entrainment (Figure 11b). If the sulfide oxidation reaction was quantitative (with no attendant fractionation) the secondary sulfate generated by sulfide oxidation could be up to 20% (fss = 0.21). Either estimate demonstrates that a substantial contribution of vent gas-derived H2S is incorporated into the local sulfate pool.

The oxygen isotope composition of pore water sulfates in Palaeochori sediments further demonstrates the production of secondary sulfate during seawater entrainment. Residual sulfate δ34S and δ18O typically evolves toward higher values during microbial sulfate reduction [26]. Contrary to this positive relationship, the paired sulfur and oxygen isotopic composition of sulfates tend to be both 34S-depleted and 18O-enriched, or invariant δ34S coupled with depletion in 18O (Figure 12). The departure from Palaeochori seawater sulfate (δ18OSO4 = 9.0‰) in either a positive or negative direction likely resulted from oxygen isotope exchange during abiotic sulfide oxidation. Spiegelei and Rocky Point pore waters with low pH (<5) and high temperature (>75°C) have high δ18OSO4 values (Figure 12). Mass balance demonstrates that the low δ34SSO4 values of these pore waters result from a mixture of seawater sulfate and 34S-depleted secondary sulfate produced by sulfide oxidation (Figure 11b). Sulfite, a sulfoxy ion, is an intermediate species produced during both sulfide oxidation and sulfate reduction. Sulfite readily exchanges oxygen with the environment and this equilibrium isotope effect determines the δ18O value of sulfate produced by oxidative or reductive sulfur cycling [27]. Ambient sources of oxygen in shallow-sea hydrothermal systems include molecular oxygen (δ18OO2 = 23.5‰), magmatic water (δ18OH2O = 6 to 8‰) and seawater (δ18OH2O = −1 to 1.5‰) [24],[97]. It is well demonstrated that seawater altered during high temperature phase separation or water-rock reactions becomes δ18O-enriched (by 1 to 2.5‰ at 300°C) [24]. The full extent of oxygen isotope fractionation between newly formed sulfate and available oxygen (Δ18OSO4-H2O = 5.9 to 17.6‰) depends on the residence time of sulfite, which rapidly exchanges oxygen at low pH [27]. Regardless of source and the associated isotope effect, the oxygen inherited from acidic and high temperature hydrothermal fluids during abiotic sulfide oxidation is 18O-enriched. The high δ18O value of geothermal waters on Milos Island (δ18OH2O = 4.5‰; aquifer temperature of 330°C) [98] is consistent with this effect.

The oxygen isotope composition of seawater and the hydrothermal fluids were not measured in this study, but the trend toward higher δ18OSO4 observed in hydrothermal pore waters (Figure 12), is consistent with oxygen isotope exchange via a sulfite intermediate. The isotopic composition of secondary sulfate formed at these sites thus provides a record of both the parent oxygen e.g. [29] and sulfur incorporated during abiotic oxidation.

The secondary sulfate production rates are likely tied to the high spatial and temporal variability of H2S delivery from the subsurface. The hydrothermal flux has been shown to fluctuate with tidal pumping, diurnal cycles, and storm activity [47],[65],[68],[69],[73]. In addition, phase-separation (boiling) at these shallow-sea hydrothermal sites can partition seawater into a chloride-rich brine and steam distillate that is low in chloride and enriched in volatile gases such as H2S, CO2, He, and H2[39]. The highly variable thermal regimes resulted in complex pore water chemistry including contributions from a H2S-rich gas that may move independently of chloride-rich fluids. The low temperature Twinkie pore waters include phase separated (low chloride) fluids and sulfate concentrations and δ34S that were similar to those in seawater. Rocky Point and Spiegelei were higher temperature sites that emit fluids with high chloride concentrations, low sulfate, and δ34SSO4 that varies with temperature. A second mass balance model normalized to the fractional input of chloride (fbrine) was developed to further constrain the system:

| (6) |

and

| (7) |

where the sulfate ([SO42−]) and chloride ([Cl−]) concentrations and δ34S values of the pore water sulfate (pw) is a mixture of seawater (sw; δ34S = 21.2‰; [SO42−] = 32.4 mM; [Cl−] = 620.3 mM) and brine. The trajectory of the model array represents the best fit to the observed pore water data (Figure 13). End member values for the brine required to fit the data include secondary sulfate produced by chemical oxidation (δ34Sbrine = −2.7‰), low sulfate concentration ([SO42−] = 0.2 mM) and high chloride content ([Cl−] = 960 mM). Pore waters from Speigelei and Rocky Point with chloride concentrations in excess of those in Aegean seawater (fbrine > 0.5) had lower δ34S sulfate values (Figure 13). Control samples with negligible fluid inputs (fbrine = 0) were isotopically identical to seawater.

Hydrothermal circulation

Downward movement of entraining (cold) oxic seawater and buoyant upward flow of (hot) fluids establish convective circulation in which solutions pass through multiple reactions zones during transport in the subsurface [4]. Regardless of the chemical pathway, an equilibrium isotope effect between dissolved H2S and anhydrite (CaSO4) veins precipitated near the seafloor can buffer the δ34S of evolved fluids [6]. Anhydrite is a common hydrothermal mineral that forms during retrograde solubility of seawater sulfate at temperatures above 150°C [99],[100]. H2S in the ascending fluids will equilibrate with sulfate in the anhydrite front, and the extent of equilibration depends upon temperature and residence time of the fluid that comes into contact with the anhydrite. Multiple sulfur isotope (32S, 33S, 34S) mass balance models indicate that the anhydrite buffer model imparts a final filter on the isotope signature of fluids that discharge on the seafloor. Based on these isotope models, a significant portion of vent sulfide in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise is derived from seawater sulfate (22% to 33%) [12],[13].

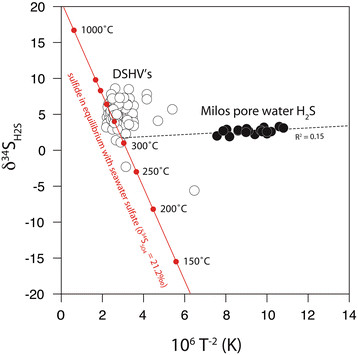

In this study of the upper 20 cm of the Palaeochori seafloor sediment, δ34S and temperature data are consistent with partial isotopic exchange between vent H2S and subsurface anhydrite (Figure 14). Isotopic exchange between sulfate and dissolved H2S increases with temperature according to the empirical equilibrium model:

| (8) |

Figure 14.

Temperature and δ 34 S of hydrothermal sulfide from deep-sea hydrothermal vents (DSHV’s; open symbols) and Milos pore waters (solid symbols). Estimates calculated for sulfide in equilibrium (red line) with seawater sulfate (δ34SSO4 = 21.2‰). The Milos regression intersects the equilibrium model at 311.4°C and δ34SH2S = 1.7‰.

where the fractionation factor between sulfate and H2S (α) is inversely proportional to temperature (T, in Kelvin) [101]. H2S in exchange with anhydrite approaches seawater values (δ34SSO4 = 21.2‰) at temperatures above 1273.2 K (1000°C). Deep-sea hydrothermal vent H2S (>1500 m water depth) have δ34S values that approximate high temperature equilibrium exchange with seawater sulfate (Figure 14). In contrast, Palaeochori H2S is out of isotopic equilibrium with seawater sulfate (δ34SSO4 = 21.2‰), yet these data fall along a mixing line that intercepts the equilibrium line at a buffered H2S value of 1.7‰ and 311.4°C. The δ34S values track a temperature dependent array from this initial value up to a maximum δ34S of 3.3‰ in the lower temperature background sediments (33.5°C). This linear departure from the initial δ34S value could represent an array of isotopic signatures attained at high temperature and those altered during non-equilibrium (enzymatic) reactions, such as microbial sulfate reduction in the low temperature sediments. Inorganic disproportionation of magmatic SO2 is another potential isotope fractionation mechanism that can produce 34S-enriched sulfate (by 16 to 21‰) and a residual H2S with low δ34S [28]; however, SO2 has not been detected in Milos vents e.g. [41] and vent H2S is not exceptionally depleted in 34S.

The ~300°C temperature estimate is consistent with geothermometry calculations for the deep-seated hydrothermal reservoir. Reaction temperatures estimated from phase equilibrium Na-K-Ca geothermometry of volcanic fluids from Milos suggests a 300-325°C reservoir [69],[102] positioned at 1–2 km depth and a shallow 248°C reservoir at 0.2-0.4 km [102]. Similar deep reservoir temperatures (345°C) and a phase separation temperature (260°C) were estimated from gas geothermometry (H2-Ar, H2-N2, H2-H2O) at Nysiros [96].

Conclusions

Much of the current understanding of hydrothermal cycling of sulfur and carbon is based on major element and isotope systematics developed from investigations of altered basalts in trenches and new crust formed along spreading centers. In general, sulfur contributions to submarine hydrothermal vents are derived from sulfur mobilized from host rock and seawater sulfate reduced during thermochemical or microbial sulfate reduction. The felsic to intermediate composition of magma at Milos and other shallow-sea vents results in vent fluids with wide-ranging chemistries. The shallow depths also expose these igneous fluids to physical mixing (tidal or wind-driven), phase separation, and microbial utilization. Chemical and biological reactions in these systems are dynamic over small spatial scales and short temporal scales. Shallow-sea hydrothermal vents along continental margins and convergence zones such as Milos have geochemical and environmental conditions that are unique from deep-sea counterparts.

The Milos vents are characterized by white (lower temperature) and orange/yellow (higher temperature) seafloor precipitates. Sulfide-sensitive films deployed in colored seafloor and background sediments captured the diffusive or advective nature of fluid discharge. Pore fluids analyzed from these same sites revealed a highly uniform sulfur isotope value for H2S in the vent gases and pore waters (δ34SH2S = 2.5‰). The shifts toward low δ34SH2S, and high δ34SSO4 and δ18OSO4 characteristic of microbial sulfate reduction was not observed within any of the sites. Sulfur isotope evidence does suggest that pore fluids in high temperature sites contain a mixture of entrained oxic seawater and a 34S-depleted pool of secondary sulfate. An equilibrium isotope model suggests that volcanic inputs are buffered to an initial δ34SH2S value of 1.7‰ by subsurface anhydrite veins. At these shallow-sea hydrothermal vent sites, the normally diagnostic biosignatures of microbial sulfate reduction (low δ34SH2S and high δ34SSO4 and δ18OSO4) were not readily differentiated from igneous sulfur inputs. Improved knowledge obtained here about the interactions between the biotic and abiotic sulfur cycle within complex natural environments will further refine geochemical proxies for biologically mediated processes recorded in the geologic record.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DF, GD, JA, and WG conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. DF, GD, JA, RP, and WG conducted the fieldwork and sample collection. WG prepared and analyzed samples for isotopic analysis. RP and JA measured pH and temperature in situ. RP analyzed anion concentrations. GD conducted the voltammetry and FK calibrated the electrodes for the accurate determination of dissolved H2S concentrations. WG, DF, and GD drafted the manuscript. RP and JA provided assistance editing and finalizing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

William P Gilhooly, Email: wgilhool@iupui.edu.

David A Fike, Email: dfike@levee.wustl.edu.

Gregory K Druschel, Email: gdrusche@iupui.edu.

Fotios-Christos A Kafantaris, Email: fotkafan@iupui.edu.

Roy E Price, Email: roy.price@stonybrook.edu.

Jan P Amend, Email: janamend@usc.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Associate Editor Richard Wilkin and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank Athanasios Godelitsas, University of Athens, for his discussion of hydrothermal systems and access to his laboratory. Paul Gorjan, Mike Brasher, and Dwight McCay assisted in the sulfur isotope analyses at Washington University in St. Louis. The research was supported through NSF funding to DAF, JPA and GKD (NSF MGG 1061476).

References

- Clark BC. In: Life in the Universe. Billingham J, editor. MIT Press, Cambridge; 1981. Sulfur: Fountainhead of Life in the Universe; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen BB. Mineralization of organic matter in the sea bed - the role of sulphate reduction. Nature. 1982;296:643–645. [Google Scholar]

- Berner RA. Burial of organic carbon and pyrite sulfur in the modern ocean: its geochemical and environmental significance. Am J Sci. 1982;282:451–473. [Google Scholar]

- Gamo T. In: Biogeochemical Processes and Ocean Flux in the Western Pacific. Sakai H, Nozaki Y, editor. Terra Scientific, Tokyo; 1995. Wide variation of chemical characteristics of submarine hydrothermal fluids due to secondary modification processes after high temperature water-rock interaction: a review; pp. 425–451. [Google Scholar]

- Henley RW, Ellis AJ. Geothermal Systems Ancient and Modern: A Geochemical Review. Earth Sci Rev. 1983;19:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmoto H, Goldhaber MB. In: Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits. Barnes HL, editor. John Wiley & Sons, New York; 1997. Sulfur and Carbon Isotopes; pp. 517–611. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA, Jonassan IR, Massoth GJ, Feely RA, Roe KK, Embley RE, Holden JF, McDuff RE, Lilley MD, Delaney JR. Seafloor eruptions and evolution of hydrothermal fluid chemistry. Philos Trans R Soc A. 1997;355:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Elderfield H, Schultz A. Mid-ocean Ridge hydrothermal fluxes and the chemical composition of the ocean. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 1996;24:191–224. [Google Scholar]

- Staudigel H, Hart SR. Alteration of basaltic glass: Mechanisms and significance for the oceanic crust-seawater budget. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1983;47:337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Edmond JM, Measures C, McDuff RE, Chan LH, Collier R, Grant B, Gordon LI, Corliss JB. Ridge crest hydrothermal activity and the balances of the major and minor elements in the ocean: The Galapagos data. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1979;46:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- German CR, Von Damm KL. In: Treatise on Geochemistry. Holland HD, Turekian KK, editor. Elsevier, Oxford; 2003. Hydrothermal Processes; pp. 181–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Shanks WC III, Rouxel OJ, Rumble D. S-33 contraints on seawater sulfate contribution in modern seafloor hydrothermal vent sulfides. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2007;71:1170–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Peters M, Strauss H, Farquhar J, Ockert C, Eickmann B, Jost CL. Sulfur cycling at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge: A multiple sulfur isotope approach. Chem Geol. 2010;269:180–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rouxel O, Ono S, Alt J, Rumble D, Ludden J. Sulfur isotope evidence for microbial sulfate reduction in altered oceanic basalts at ODP Site 801. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2008;268:110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H, Des Marais DJ, Ueda A, Moore JG. Concentrations and isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in ocean-floor basalts. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48:2433–2441. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(84)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees CE, Jenkins WJ, Monster J. The sulphur isotopic composition of ocean water sulphate. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1978;42:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- Chaussidon M, Albarede F, Sheppard SMF. Sulphur isotope variations in the mantle from ion microprobe analyses of micro-sulphide inclusions. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1989;92:144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chaussidon M, Albarede F, Sheppard SMF. Sulphur isotope heterogeneity in the mantle from ion microprobe measurements of sulphide inclusions in diamonds. Nature. 1987;330:242–244. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield DE. In: Stable Isotope Geochemistry. Valley JW, Cole DR, editor. Mineralogical Society of America, Washington DC; 2001. Biogeochemistry of Sulfur Isotopes; pp. 607–636. [Google Scholar]

- Sim MS, Ono S, Donovan K, Templer SP, Bosak T. Effect of electron donors on the fractionation of sulfur isotopes by a marine Desulfovibrio sp. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2011;75:4244–4259. [Google Scholar]

- Alt JC, Burdett JW. In: Proc. ODP, Sci. Results, 129: College Station TX (Ocean Drilling Program) Larson RL, Lancelot Y, editor. 1992. Sulfur in Pacific deep-sea sediments (Leg 129) and implications for cycling of sediment in subduction zones; pp. 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield DE. The Evolution of the Earth Surface Sulfur Reservoir. Am J Sci. 2004;304:839–861. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks WC. Stable Isotopes in Seafloor Hydrothermal Systems: Vent fluids, hydrothermal deposits, hydrothermal alteration, and microbial processes. Rev Mineral Geochem. 2001;43:469–525. [Google Scholar]

- Shanks WC, III, Böhlke JK, Seal RR. , II. Seafloor Hydrothermal Systems: Physical, Chemical, Biological, and Geological Interactions. AGU, Washington, DC; 1995. Stable isotopes in mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal systems: Interactions between fluids, minerals, and organisms; pp. 194–221. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba H, Sakai H. Oxygen isotope exchange rate between dissolved sulfate and water at hydrothermal temperatures. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1985;49:993–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner B, Bernasconi SM, Kleikemper J, Schroth MH. A model for oxygen and sulfur isotope fractionation in sulfate during bacterial sulfate reduction processes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2005;69:4773–4785. [Google Scholar]

- Müller IA, Brunner B, Coleman M. Isotopic evidence of the pivotal role of sulfite oxidation in shaping the oxygen isotope signature of sulfate. Chem Geol. 2013;354:186–202. [Google Scholar]

- Craddock PR, Bach W. Insights to magmatic-hydrothermal processes in Manus back-arc basin as recorded by anhydrite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2010;74:5514–5536. [Google Scholar]

- Teagle DAH, Alt JC, Halliday AN. Tracing the chemical evolution of fluids during hydrothermal recharge: Constraints from anhydrite recovered in ODP Hole 504B. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1998;155:167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Marini L, Fiebig J. In: The Geology, Geochemistry and Evolution of Nisyros Volcano (Greece). Implications for the Volcanic Hazards. Hunziker JC, Marini L, editor. Section des sciences de la Terre, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne; 2005. Fluid geochemistry of the magmatic-hydrothermal system of Nisyros (Greece) pp. 121–163. [Google Scholar]

- Marini L, Gambardella B, Principe C, Arias A, Brombach T, Hunziker JC. Characterization of magmatic sulfur in the Aegean island arc by means of the δ34S values of fumarolic H2S, elemental S, and hydrothermal gypsum from Nisyros and Milos Islands. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2002;200:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Peters M, Strauss H, Petersen S, Kummer N, Thomazo C. Hydrothermalism in the Tyrrhenian Sea: Inorganic and microbial sulfur cycling as revealed by geochemical and multiple sulfur isotope data. Chem Geol. 2011;280:217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Amend JP, Rogers KL, Meyer-Dombard DR. In: Sulfur Biogeochemistry - Past and Present: Geological Society of America Special Paper 379. Amend JP, Edwards KJ, Lyons TW, editor. Geological Society of America, Boulder; 2004. Microbially mediate sulfur-redox: Energetics in marine hydrothermal vent systems; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov VG, Gebruk AV, Mironov AN, Moskalev LI. Deep-sea and shallow-water hydrothermal vent communities: Two different phenomena? Chem Geol. 2005;224:5–39. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield DA, Massoth GJ, McDuff RE, Lupton JE, Lilley MD. Geochemistry of hydrothermal fluids from Axial Seamount hydrothermal emissions study vent field, Juan de Fuca Ridge: Subseafloor boiling and subsequent fluid-rock interaction. J Geophys Res. 1990;95:12895–12922. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff JL, Rosenbauer RJ. The critical point and two-phase boundary of seawater, 200–500°C. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1984;68:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Foustoukos DI, Seyfried WE. Fluid Phase Separation Processes in Submarine Hydrothermal Systems. Rev Mineral Geochem. 2007;65:213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi J-i, Urabe T. In: Backarc Basins. Taylor B, editor. Springer US, New York; 1995. Hydrothermal Activity Related to Arc-Backarc Magmatism in the Western Pacific; pp. 451–495. [Google Scholar]

- Price RE, Savov I, Planer-Friedrich B, Bühring SI, Amend JP, Pichler T. Processes influencing extreme As enrichment in shallow-sea hydrothermal fluids of Milos Island, Greece. Chem Geol. 2013;348:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Druschel GK, Rosenberg PE. Non-magmatic fracture-controlled hydrothermal systems in the Idaho Batholith: South Fork Payette geothermal system. Chem Geol. 2001;173:271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Dando PR, Aliani S, Arab H, Bianchi CN, Brehmer M, Cocito S, Fowler SW, Gundersen J, Hooper LE, Kölbl R, Kuever J, Linke P, Makropoulos KC, Meloni R, Miquel J-C, Morri C, Müller S, Robinson C, Schlesner H, Sievert SM, Stöhr R, Stüben D, Thomm M, Varnavas SP, Ziebis W. Hydrothermal Studies in the Aegean Sea. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part B: Hydrology, Oceans and Atmosphere. 2000;25:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dando PR, Hughes JA, Leahy Y, Niven SJ, Taylor LJ, Smith C. Gas venting rates from submarine hydrothermal areas around the island of Milos, Hellenic Volcanic Arc. Continent Shelf Res. 1995;15:913–929. [Google Scholar]

- Price RE, Amend JP, Pichler T. Enhanced geochemical gradients in a marine shallow-water hydrothermal system: Unusual arsenic speciation in horizontal and vertical pore water profiles. Appl Geochem. 2007;22:2595–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Price RE, Pichler T. Distribution, speciation and bioavailability of arsenic in a shallow-water submarine hydrothermal system, Tutum Bay, Ambitle Island, PNG. Chem Geol. 2005;224:122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone FJ, Pawlak G, Stanton TP, McManus MA, Glazer BT, DeCarlo EH, Bandet M, Sevadjian J, Stierhoff K, Colgrove C, Hebert AB, Chen IC. Kilo Nalu: Physical/biogeochemical dynamics above and within permeable sediments. Oceanography. 2008;21:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert AB, Sansone FJ, Pawlak GR. Tracer dispersal in sandy sediment porewater under enhanced physical forcing. Continent Shelf Res. 2007;27:2278–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel M, Sievert SM, Vetriani C, Foustoukos DI, Giovannelli D, Le Bris N. Eco-geochemical dynamics of a shallow-water hydrothermal vent system at Milos Island, Aegean Sea (Eastern Mediterranean) Chem Geol. 2013;356:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Truesdell A, Nehring N. Gases and water isotopes in a geochemical section across the Larderello, Italy, geothermal field. Pure Appl Geophys. 1978;117:276–289. [Google Scholar]