SUMMARY

Previously, two riboswitch classes have been identified that sense and respond to the hypermodified nucleobase called pre-queuosine1 (preQ1). The enormous expansion of available genomic DNA sequence data creates new opportunities to identify additional representatives of the known riboswitch classes and to discover novel classes. We conducted bioinformatics searches on microbial genomic DNA datasets to discover numerous additional examples belonging to the two previously known riboswitch classes for preQ1 (classes preQ1-I and preQ1-II), including some structural variants that further restrict ligand specificity. Additionally, we discovered a third preQ1-binding riboswitch class (preQ1-III) that is structurally distinct from previously known classes. These findings demonstrate that numerous organisms monitor the concentrations of this modified nucleobase by exploiting one or more riboswitch classes for this widespread compound.

INTRODUCTION

In all cells and in many viruses, there exist many types of structured noncoding RNAs with important genetic and catalytic roles. In bacteria, riboswitches are a very common type of noncoding RNA that are present in the 5′-untranslated regions (5′ UTRs) of certain mRNAs (Henkin, 2008; Montange and Batey, 2008; Serganov and Nudler, 2013). Riboswitches selectively recognize specific small molecules or ions and this binding interaction triggers the RNA to alter expression of the open reading frame (ORF) located within its mRNA. Typically, each riboswitch consists of an aptamer domain that forms the binding pocket for the target metabolite or ion and an expression platform, which overlaps with the aptamer region of the riboswitch and exerts genetic control by one of a number of possible mechanisms (Breaker, 2012).

Most ligands have only one known riboswitch class, but there are a few notable exceptions. The coenzyme S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) and the related molecule S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine (SAH) are recognized by no fewer than five distinct riboswitch classes (Wang and Breaker, 2008; Breaker, 2012), the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP by two (Sudarsan et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010), and the magnesium ion by two (Ramesh and Winkler, 2010). These observations indicate that nature can exploit the considerable structural capabilities of RNA to form a variety of structures to achieve similar molecular recognition and gene control functions. Researchers must therefore consider the possibility that more rare classes of riboswitches might exist for ligands that are already known to be sensed by some of the exceptionally common riboswitch classes (Ames and Breaker, 2010).

Two distinct riboswitch classes for pre-queuosine1 (preQ1) also have been discovered previously (Roth et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2008). PreQ1 is a guanine-derived nucleobase (Figure 1A) that is known to be incorporated in the wobble position of tRNAs containing the GUN anticodon sequence and then further modified to yield queuosine (Q) (Iwata-Reuyl, 2008). The presence of Q in tRNAs improves their ability to read degenerate codons (Meier et al., 1985), while the absence of enzymes involved in Q biosynthesis or salvage results in deleterious phenotypes in a wide array of organisms (Durand et al., 2000; Rakovich et al., 2011). Despite the near-ubiquitous presence of preQ1 in organisms (Iwata-Reuyl, 2008), much remains unknown regarding the function of this modified nucleobase and its derivatives in cells. Therefore, the discovery of additional representatives of preQ1 riboswitches and their gene associations might facilitate new discoveries that will expand our understanding of preQ1 biology.

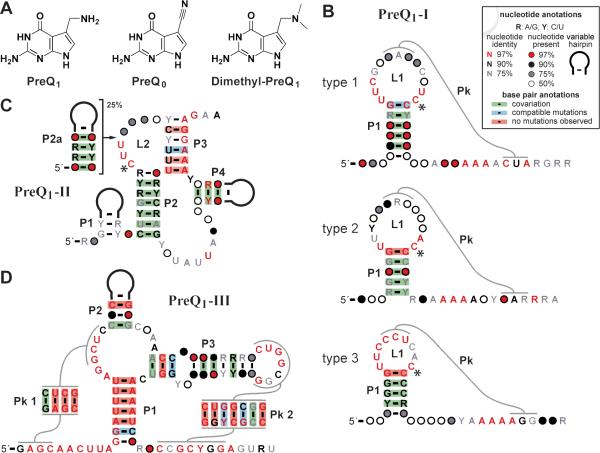

Figure 1. Riboswitch classes that sense preQ1 and related molecules.

(A) Chemical structures of preQ1, preQ0, and dimethyl-preQ1. (B) Consensus sequences and secondary structure models of the three types of preQ1-I riboswitches. Stem and loop substructures are labeled P and L, respectively, and pseudoknots (Pk) are identified by the curved line. The asterisks identify C nucleotides that form cis (preQ1-I) or trans (preQ1-II) Watson-Crick base pairs with the ligand. (C) PreQ1-II riboswitch consensus model. (D) PreQ1-III riboswitch consensus model. Other annotations are as described in B. See Supplemental Information for the alignments and methods used to generate the consensus models.

PreQ1-I riboswitch aptamers (Figure 1B) are among the smallest of all known riboswitches and the function of a minimal aptamer as short as 34 nucleotides has been validated previously (Roth et al., 2007; Klein et al., 2009). When this class was discovered, two subclasses (or types) based on nucleotide identity in the loop region of the hairpin were identified. As defined previously (Roth et al., 2007), type 1 preQ1-I riboswitches, observed in the phyla Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, feature a conserved 5′-UUCR sequence in the start of the L1 loop and a conserved 5′-UC sequence at the end of this loop (Figure 1B, top). In contrast, type 2 preQ1-I riboswitches, seen in Firmicutes, were found to possess a conserved 5′-YUAR sequence in the middle of L1 and a conserved 5′-AC sequence at its end (Figure 1B, middle). Both types feature loop regions that are between 10-15 nucleotides in length.

Subsequently, a second distinct riboswitch class was identified that specifically recognizes preQ1 (Meyer et al., 2008; Liberman et al., 2013). Riboswitches of this class, termed preQ1-II, have a larger and more complex consensus sequence and structural model compared to preQ1-I riboswitches. Representatives of this class have an average of 58 nucleotides in the aptamer, which forms as many as five base-paired substructures (Figure 1C). PreQ1-II riboswitches were observed only in Lactobacillales, an order within the phylum Firmicutes.

Since class I and class II riboswitches have similar ligand affinities and molecular recognition characteristics, the more restricted distribution of preQ1-II riboswitches might be due simply to its larger and more complex structure. Both class I and II riboswitches primarily exploit a conserved cytidine nucleotide to bind preQ1, though with different molecular interactions. PreQ1-I riboswitches employ a cis-Watson-Crick interaction between preQ1 and a conserved cytidine in L1 (Figure 1B) (Roth et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2010; Klein et al., 2009; Feng et al., 2011; Petrone et al., 2011; Jenkins et al., 2011), whereas preQ1-II riboswitches utilize a trans-Watson-Crick interaction between preQ1 and a conserved cytidine in L2 (Figure 1C) (Meyer et al., 2008; Liberman et al., 2013). Regardless, members of both riboswitch classes have higher affinities for preQ1 than for its precursor pre-queuosine0 (preQ0) or the analog dimethyl-preQ1 (dimethyl-preQ1) (Figure 1A) (Roth et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2008). Therefore, superior function does not appear to be the reason why the smaller preQ1-I riboswitch representatives are more common in biology.

With the dramatic reductions in the costs associated with DNA sequencing, the size of the aggregate database for bacterial genomic DNA sequences has been growing rapidly. Access to additional novel DNA sequences increases the probability that bioinformatics search algorithms will reveal novel variants of known riboswitch classes. For example, we previously used comparative sequence analysis methods to identify variant glmS ribozymes with distinct structural features (McCown et al., 2011) and additional representatives of purine riboswitches that exhibit altered ligand specificities (Mandal and Breaker, 2004; Kim et al., 2007). Recently, we have identified additional variants of thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) riboswitches that have altered ligand specificity (Breaker laboratory, unpublished data).

In this study, we have uncovered the existence of a third type of preQ1-I riboswitches. Moreover, by permitting additional insertions and deletions within computational models of the preQ1-II riboswitch class, we observed a new variant type that possesses an additional hairpin extremely close to the predicted ligand-binding site. Lastly, we discovered a third riboswitch class for preQ1, which is distinct structurally from the other two riboswitch classes (Figure 1D). Members of this preQ1-III riboswitch class were found to bind to preQ1 with affinities similar to those of the other two preQ1-sensing riboswitch classes, which indicates that bacteria employ at least three distinct riboswitch classes for this modified nucleobase.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

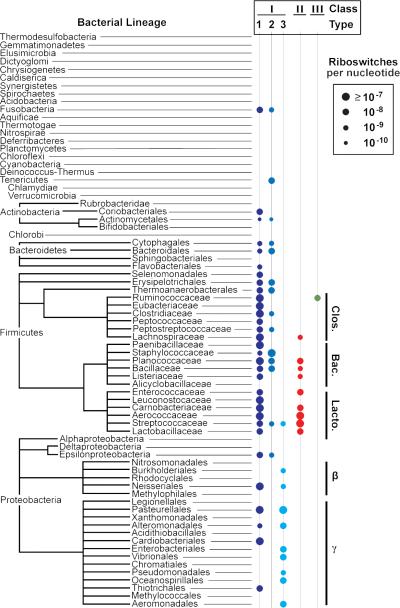

A Type 3 Aptamer Architecture for PreQ1-I Riboswitches

Bioinformatics searches (see Experimental Procedures) were conducted for additional and variant preQ1-I riboswitches by analyzing previous multiple-sequence alignments for this class (Roth et al., 2007; Burge et al., 2012). We conducted searches with expanded nucleotide sequence databases and observed numerous preQ1-I riboswitches that previously were unannotated (Table S1; Table S4). While we found additional riboswitches that conformed to the type 1 and type 2 consensus models, we also found numerous putative preQ1-I riboswitches that did not conform readily to either type. These RNAs were used to create an independent consensus model called type 3 (Figure 1B, bottom). Type 3 preQ1-I RNAs, which exist almost exclusively in Gammaproteobacteria (Figure 2; Table S1; Table S5), possess an L1 region that is between 9 and 10 nucleotides. The loops are highly biased in favor of pyrimidine nucleotides to such extent that several members have no purines in L1. All three types are observed to possess variable-sequence hairpins either before P1 or immediately after it, although these optional substructures are present in only about 5% of the representatives.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic distribution of three preQ1 riboswitch classes.

Left-most names are bacterial phyla, while names further to the right are subdivisions of the phyla as indicated by lines. Additional phylogenetic levels are depicted for the phyla Firmicutes and Proteobacteria due to the large number of preQ1 riboswitch representatives therein. Phyla for which less than 10 Mbp of genomic sequence exists are excluded from this tree.

Unlike other preQ1-I riboswitches, type 3 RNAs were found only in association with yhhQ genes, which are proposed to code for inner membrane proteins of unknown function (Granseth et al., 2005). However, other preQ1-I riboswitches also associate with yhhQ genes (Roth et al., 2007), and therefore we speculated that type 3 aptamers most likely recognize preQ1. Furthermore, despite the differences in the loop region of type 3 RNAs, the nucleotides that are key for binding preQ1 appear to be present, as are the major architectural features seen with other preQ1-I riboswitches. The 3′ portion of the pseudoknot in all type 3 riboswitches is predicted to be part of the ribosome binding site for the downstream ORF, and therefore ligand binding is predicted to repress translation.

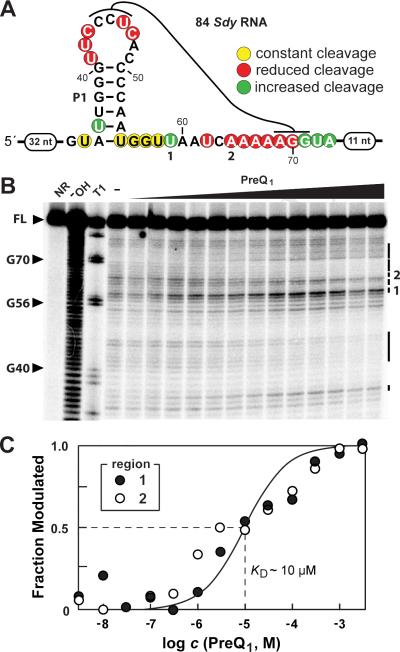

In-line probing assays (Soukup and Breaker, 1999; Regulski and Breaker, 2008) were conducted to assess ligand binding. A candidate type 3 preQ1-I aptamer from Shigella dysenteriae, called 84 Sdy RNA (Figure 3A), was subjected to in-line probing (see Experimental Procedures). This RNA indeed undergoes structural modulation upon the addition of preQ1 (Figure 3B) and nucleotide positions that undergo a reduction in spontaneous cleavage (red circles) cluster in the conserved regions of the RNA. The in-line probing data were used to estimate an apparent dissociation constant (KD) for preQ1 of ~10 μM (Figure 3C). The KD values for preQ0 (~5 μM) and dimethyl-preQ1 (~25 μM) are similar to that for preQ1 (Figure S1), which is in accordance with previously studied preQ1-I riboswitch representatives (Roth et al., 2007). Although these values are an order of magnitude poorer than those observed for a Bacillus subtilis type 2 preQ1-I riboswitch previously studied, such variation in binding affinity among members of a riboswitch class has many precedents (Jenkins et al., 2011; Liberman et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2013).

Figure 3. A type 3 preQ1-I riboswitch binds preQ1.

(A) Sequence and secondary structure model for 84 Sdy RNA, a type 3 preQ1-I riboswitch from Shigella dysenteriae. Colored circles represent in-line probing data derived from B wherein the locations are approximated with the aid of marker lanes. Notations 1 and 2 are regions identified in B and analyzed in C. (B) In-line probing results using 5′ 32P-labeled 84 Sdy RNA. NR, − OH, and T1 designate full length (FL) RNAs subjected to no reaction, partial digestion with alkali (cleaves RNA at every position), and partial digestion with RNase T1 (cleaves RNA after G residues). Other lanes include precursor RNAs exposed to in-line reaction conditions without preQ1 (− ) or with increasing amounts of preQ1 (1 nM to 3 mM). Vertical lines identify cleavage products that are altered upon preQ1 addition and the numbered lines identify the regions that were quantified to estimate a KD value. (C) Plot of the fraction of 84 Sdy RNAs bound to ligand versus the logarithm of the concentration of preQ1 inferred from band intensity changes at regions 1 (cleavage after U59) and 2 (cleavage after A64) depicted in B. The solid line depicts a theoretical binding curve for a 1-to-1 interaction between preQ1 and aptamer with a KD of 10 μM.

A Second Aptamer Type for PreQ1-II Riboswitches

Since the preQ1-II riboswitch class was found originally only within the family Streptococcaceae, it was suspected that additional riboswitch variants of this class might also exist (Meyer et al., 2008). Bioinformatics searches conducted with an expanded genomic sequence database revealed numerous examples of a variant of preQ1-II riboswitches that comprise approximately 25% of all representatives (Figure 1C; Table S2; Table S4; Table S5). The variant preQ1-II structure is similar to the prototypical preQ1-II riboswitch consensus, but contains an additional hairpin (P2a) within L2, which occurs after the conserved sequence 5′-CUU that includes the preQ1-binding cytidine (Meyer et al., 2008; Liberman et al., 2013).

For all preQ1-II riboswitches that were found in organisms whose genomes are fully sequenced, the majority are in the Streptococcaceae and Lactobacillaceae families, which is consistent with previous findings (Meyer et al., 2008). In addition, one preQ1-II riboswitch was found in the Clostridiales order. However, we also found variant preQ1-II riboswitches in closely related families within the Lactobacillales order (Figure 2). In each instance, the ribosome binding site for the downstream ORF again is predicted to be part of each preQ1-II aptamer. Therefore ligand binding is expected to repress protein expression, as with other members of this class (Meyer et al., 2008; Liberman et al., 2013).

All but one of the preQ1-II riboswitches appear in the predicted 5′ UTRs for COG4708 genes, which code for a predicted queuosine transporter (queT) (Meyer et al., 2008; Johansson et al., 2011). The exception is a putative preQ1-II riboswitch present in the predicted 5′ UTR of a metK gene (S-adenosylmethionine synthase) (Greene, 1996) from Lachnospiraceae bacterium 3_1_57FAA_CT1. Interestingly, this preQ1-II riboswitch representative appears to occur in tandem with a SAM-I riboswitch representative (Figure S2). Tandem riboswitch architectures are rare, but several examples examined previously operate as two-input Boolean logic gates (Sudarsan et al., 2006; Ames et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011), wherein two different ligands regulate gene expression. Associations between SAM riboswitches and SAM synthase genes are very common (Wang et al., 2008) because the presence of abundant SAM logically triggers the repression of SAM synthase gene expression. However, the regulatory utility of linking SAM biosynthesis to the concentration of preQ1 remains obscure. SAM is used in the process of maturing preQ1 into Q, and is used extensively in wyosine and wybutosine synthesis in eukaryotes (Noma et al., 2006; Iwata-Reuyl, 2008). Perhaps these biochemical connections between SAM and preQ1 might be the reason for the existence of this rare tandem riboswitch architecture.

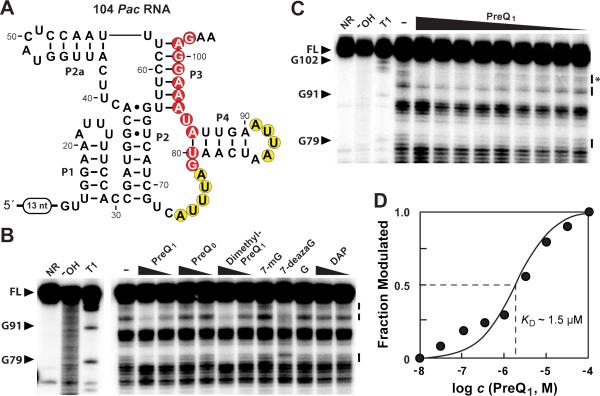

In-line probing experiments were conducted to determine whether the additional P2a hairpin found in variant preQ1-II riboswitches had any effect on the molecular recognition characteristics compared to those that lack this substructure. The 104 Pac RNA construct (Figure 4A), a variant preQ1-II aptamer from Pediococcus acidilactici, was examined with various concentrations of preQ1 (Figure 4B, C) and assorted preQ1 analogs (Figure 4B). As expected, compounds preQ1, dimethyl-preQ1, and 7-deazaguanine induce structural modulation. The KD values for preQ1 (1.5 μM) (Figure 4D) and dimethyl-preQ1 (1.3 μM) (Figure S3) are comparable to the affinities for these two compounds exhibited by the canonical preQ1-II riboswitches from S. pneumoniae (Meyer et al., 2007). In contrast, preQ0, guanine, 7-methylguanine, and 2,6-diaminopurine are rejected by the RNA at concentrations as high as 100 micromolar. Curiously, preQ0 and guanine are not strongly discriminated against by either the canonical preQ1-II riboswitch from Streptococcus pneumoniae (Meyer et al., 2008) or the type II preQ1-I riboswitch aptamer from B. subtilis (Roth et al., 2007). However, it is not clear if the structural adaptation of variant preQ1-II riboswitches that gives rise to increased ligand selectivity is biologically important.

Figure 4. A variant preQ1-II riboswitch strongly discriminates against preQ0.

(A) Sequence and proposed secondary structure for 104 Pac RNA, a variant preQ1-II riboswitch from Pediococcus acidilactici. (B) In-line probing of 5′ 32P-labeled 104 Pac RNA with preQ1, preQ0, dimethyl-preQ1 (all at 0.1 and 100 μM), and various analogs as indicated. 7-mG is 7-methyl-guanine (100 μM), 7-deazaG is 7-deazaguanine (100 μM), G is guanine (10 μM), and DAP is 2,6-diaminopurine (0.1 and 100 μM). Asterisk denotes the band used to estimate the KD. Other annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3B. (C) In-line probing of 5′ 32P-labeled 104 Pac RNA with various concentrations of preQ1 (100 μM to 10 nM from right to left). (D) Plot of the fraction of 104 Pac RNA whose structure has been modulated by bound ligand versus the logarithm of the concentration of preQ1 (data derived from C). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3C.

It has been demonstrated that preQ1-II riboswitches wherein the P4 stem has been deleted exhibit only an order of magnitude reduction in ligand affinity (Soulière et al., 2013). Therefore, we also conducted bioinformatics searches based on a modified consensus model for preQ1-II riboswitches that lacks a P4 stem. Although we did not find any natural examples of riboswitches with a P4 deletion, it remains possible that representatives with this structural feature could exist either in genomes yet to be sequenced or with accompanying alterations that obscure them from our bioinformatics searches.

A Third Riboswitch Class for PreQ1

In addition to investigating variants within the preQ1-I and preQ1-II riboswitch classes, we used bioinformatics searches to detect candidates for new preQ1 riboswitch classes. Specifically, we compared the 5′ UTRs of genes encoding the preQ1-related COG4708 domain (Roth et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2008) using previously established methods (Weinberg et al., 2010). A total of 86 representatives of a novel conserved RNA motif (Figure 1D) were identified, with all but three occurring in environmental DNA samples (Table S3; Table S4; Table S5). The three fully-sequenced genomes that possess the conserved RNA are from organisms in the family Ruminococcaceae. After conducting an expanded search for representatives of this motif, examples were observed exclusively in the 5′ UTRs of COG4708 genes, which are also commonly associated with preQ1-I and preQ1-II riboswitch classes (Roth et al., 2007; Meyer et al., 2008).

The predicted RNA architecture consists of three base-paired regions (P1 through P3), a four nucleotide M-type pseudoknot (Pleij, 1990) formed from sequences located between the region immediately before P1 and the junction region between P1 and P2, and another possible pseudoknot formed between L3 and the 3′ tail. However, the first pseudoknot is short, the P1 stem is exceptionally A•U-rich, and nucleotides contributing to the second pseudoknot can be deleted without adverse effects (see below). These observations, coupled with the fact that these predicted substructures show little evidence of covariation, casts some doubt on the accuracy of the consensus structural model.

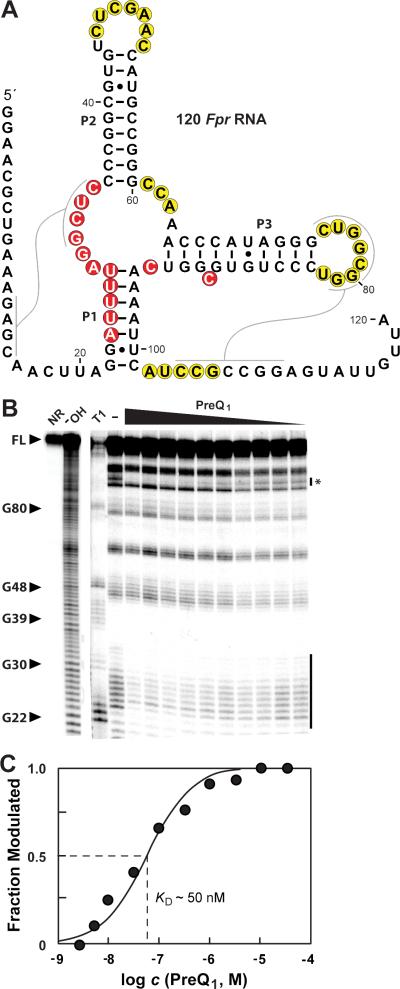

To assess ligand binding characteristics, the 120 Fpr RNA construct (Figure 5A), a representative of this riboswitch candidate from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, was used for inline probing experiments with preQ1 (Figure 5B) and related compounds. The KD values observed with 120 Fpr RNA for preQ1 (50 nM) (Figure 5C) and dimethyl-preQ1 (800 nM) (Figure S4) are consistent with the hypothesis that this RNA is a representative of an aptamer domain of a novel preQ1 riboswitch class. Compared to representatives of other classes, the 120 Fpr RNA more strongly discriminates against preQ0 (Figure S5), as the KD for this compound is at least two orders of magnitude poorer than for preQ1.

Figure 5. A preQ1-III riboswitch from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii binds preQ1.

(A) Sequence and predicted secondary structure of 120 Fpr RNA, a preQ1-III riboswitch candidate. Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3A. (B) In-line probing analysis of 5′ 32P-labeled 120 Fpr RNA with various concentrations of preQ1 (100 μM to 3.3 nM from left to right). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 4C. The NR and − OH lanes, from the same gel but separated by one lane, are depicted at lower intensity than the remainder of the image to improve clarity of alkaline ladder. Asterisk denotes the band used to estimate the KD. (C) Plot of the fraction of 120 Fpr RNA whose structure has been modulated by bound ligand versus the logarithm of the concentration of preQ1 (data derived from C). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3C.

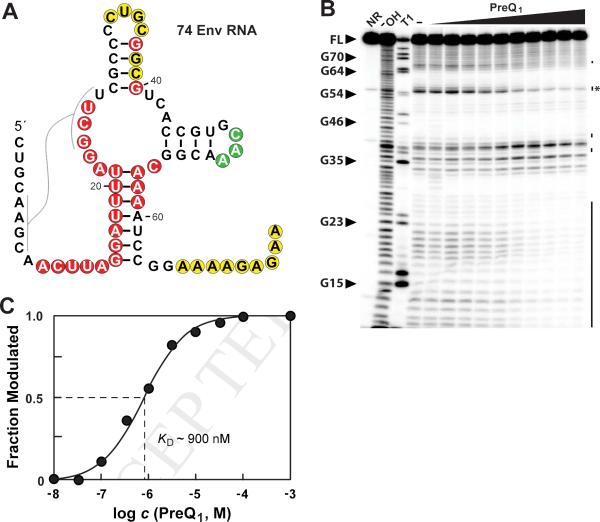

We also conducted an in-line probing analysis on an additional preQ1-III aptamer, called 74 Env RNA, which was derived from an environmental sequence (Figure 6A). This RNA undergoes robust changes in its pattern of spontaneous RNA cleavage on the addition of preQ1 (Figure 6B) and exhibits a KD of ~900 nM (Figure 6C). Therefore, both preQ1-III riboswitch aptamers examined yield in-line probing results upon addition of preQ1 that are largely consistent with the proposed secondary-structure model, including the first predicted pseudoknot and A•U-rich P1 substructures. Indeed, the addition of preQ1 appears to promote formation of these two structures.

Figure 6. A preQ1-III riboswitch from environmental sequences binds preQ1.

(A) Sequence and predicted secondary structure of 74 Env RNA, a preQ1-III riboswitch from an environmental sequence. Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3A. (B) In-line probing analysis of 5′ 32P-labeled 74 Env RNA with various concentrations of preQ1 (1 mM to 10 nM from left to right). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 4C. (C) Plot of the fraction of 74 Env RNA whose structure has been modulated by bound ligand versus the logarithm of the concentration of preQ1 (data derived from C). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3C.

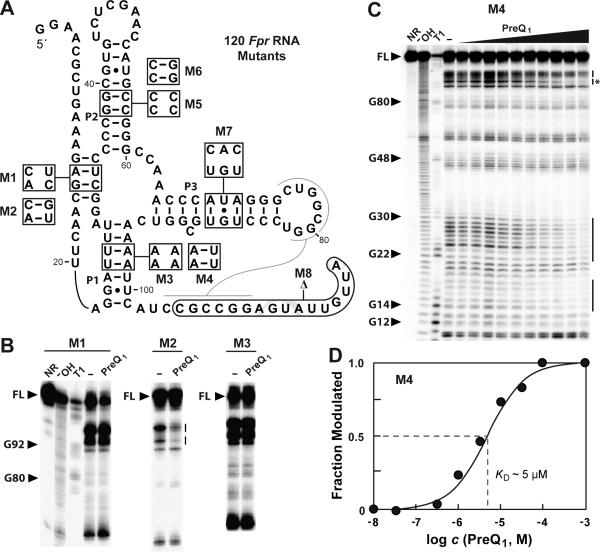

To further assess the structural model, we introduced mutations into the 120 Fpr RNA construct (Figure 7A) and conducted additional binding studies. The importance of the pseudoknot was evaluated by the introduction of disruptive (M1) and compensatory (M2) mutations into this substructure. As expected, M1 causes a loss of ligand binding while M2 restores function (Figure 7B, Figure S6). Mutations M3 and M4 were used to assess the importance of the predicted P1 stem. Again, as expected, disruption of the P1 stem causes a near complete loss of preQ1 binding. Importantly, the mutations in the M3 RNA also alter highly-conserved nucleotides, which could have independently caused the loss of function. However, M4 exhibits a substantial restoration of function (KD ~5 μM). This mutant retains binding function, albeit with a ~100-fold reduction in affinity, despite having changes to four conserved nucleotides (Figure 7C and D). This finding indicates that the formation of P1 is more important to binding than are the conserved nucleotides that form this substructure.

Figure 7. Analyses of various 120 Fpr RNA mutants by in-line probing.

(A) Locations (boxes) and nucleotide identities of the mutants examined. (B) In-line probing results for mutants M1, M2 and M3. Gel images depict only the region containing the full-length RNA through nucleotide 60, which includes the major site of modulation near nucleotide 90. Inline probing reactions were conducted in the absence (− ), or in the presence of 10 μM preQ1. (C) In-line probing of mutant M4 with increasing amounts of preQ1 (10 nM to 1 mM). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 4C. (D) Plot of the fraction of 120 Fpr M4 RNA whose structure has been modulated by bound ligand versus the logarithm of the concentration of preQ1 (data derived from C). Annotations are as described in the legend to Figure 3C.

Mutants M5 and M6 that, respectively, disrupt and restore the formation of stem P2 also cause the loss and restoration of ligand binding, as expected if P2 is critical for aptamer function (Figure S6). In contrast, mutant M7 largely retains ligand binding affinity, suggesting that more substantive mutations might be needed to disrupt the formation of this strong hairpin. Furthermore, deletion of 16 nucleotides from the 3′ terminus of the RNA does not adversely affect ligand binding (Figure S6, M8). Some of the residues deleted to form M8 are conserved among most representatives, suggesting these might be functionally relevant. An exception is the example from environmental DNA that lacks these nucleotides (Figure 7B), suggesting that they are not essential for aptamer formation. However, the conserved nucleotides appear to serve as ribosome binding sites among many representatives. Therefore the possible pseudoknot might represent an expression platform that precludes translation initiation when preQ1 is bound. In summary, our mutational data indicates that the key sequence and structural elements are confined to the consensus aptamer model derived from comparative sequence analysis (Figure 1D).

Conclusions

The preQ1-III riboswitch class represents the third distinct consensus sequence and structural architecture that senses and responds to preQ1. To date, only the collection of SAM-sensing riboswitches manifest more distinct RNA structures for a specific ligand (Breaker, 2012). While the additional variants for preQ1-I and -II riboswitch classes and the newly discovered preQ1-III riboswitch class increase the distribution of organisms that possess such riboswitches, there remain numerous bacterial phyla that do not possess any known preQ1-sensing riboswitch (Barrick and Breaker, 2007) (Figure 2). It is not clear why these three riboswitch classes for preQ1 are not more widespread among the bacterial lineages. One intriguing possibility is that there are even more classes remaining to be discovered, although different methods of regulating queuosine biosynthesis in these phyla might also have gone undetected.

Regardless, the widespread distribution of queuosine biosynthesis and transport genes in many species (Iwata-Reuyl, 2008), including some viruses (Sabri et al., 2011; Holmfeldt et al., 2013) indicates that this compound is critical for many biological systems. This observation, coupled with the discovery of a diverse collection of riboswitches for this modified base suggests that the origin of preQ1 might date back to the time of the RNA World (Gilbert, 1986; Breaker, 2012). It is known that Q-containing tRNAs are important for translation fidelity (Bienz and Kubli, 1981; Meier et al., 1985; Urbonavicius et al., 2001). PreQ1 and Q biosynthesis genes are required for effective nitrogen-fixing symbiosis between Sinorhizobium meliloti and the barrel clover plant (Marchetti et al., 2013). Also, glutamyl-Q, another Q derivative, has been linked to effective stress response in S. flexneri (Caballero et al., 2012), while Q-deficiency halts tyrosine production in germ-free mice (Rakovich et al., 2011). In human and murine cancer cells, lack of Q-modification in tRNAs has been associated with cell proliferation, anaerobic metabolism, and malignancy (Elliot et al., 1984; Pathak et al., 2008). All these phenotypes of Q deficiency highlight the importance many cells place on this modified nucleotide and its derivatives.

The diversity of preQ1-responsive riboswitches indicates that RNA has the structural and functional characteristics needed to serve as the primary sensor for this key modified nucleobase. Given the biological importance of preQ1, perhaps it is not surprising that riboswitches for this compound rank among the top 12 most common classes (Breaker, 2012). Representatives of another nucleobase-sensing riboswitch class, the purine-sensing riboswitches, whose variants respond selectively to guanine, adenine, or 2′ deoxyguanosine, are even more common. Despite the abundance of preQ1- and purine-sensing riboswitches, there are no riboswitches known presently for other nucleobases, modified or unmodified. Many other modified nucleobases are created by in situ alteration of a genetically-encoded nucleotide, whereas preQ1 exists as a separate metabolite that is grafted into an RNA chain. Therefore, most other modified nucleobases are not required to be present as free compounds (Ferré-D′Amaré, 2003; Noma et al., 2006; Iwata-Reuyl, 2008), which might provide some explanation for the lack of certain riboswitch classes for these compounds.

With the discovery of each new riboswitch class, a greater fraction of the super-regulon controlled by the metabolite ligand is revealed. This is particularly useful for exploring the biological roles of bacterial signaling compounds such as c-di-GMP (Sudarsan et al., 2008) and c-di-AMP (Nelson et al., 2013). Specifically, the location of a riboswitch immediately upstream of a gene creates a functional link between the signaling compound and the gene product. Most riboswitch classes sense fundamental metabolic intermediates or end products, and therefore they routinely control only those genes whose protein products synthesize or transport these compounds. However, rare gene associations can reveal otherwise hidden links between metabolites and biological processes. For example, the tandem arrangement of riboswitches for SAM and preQ1 suggests that other unknown functions for queuosine and related compounds are likely to be found.

SIGNIFICANCE

The modified guanine base preQ1 and its nucleoside derivative queuosine are present in many organisms, yet the biochemical roles of this natural derivative are not fully understood. Previously, two distinct classes of riboswitches had been reported that selectively bind preQ1 and its close derivatives and regulate the expression of genes for biosynthesis or import of this compound. Given that many organisms from all three domains of life synthesize or import preQ1, it is possible that this modified guanine compound emerged during the RNA World – well before the last common ancestor of extant life forms. If true, the common classes of riboswitches for preQ1 might also have an ancient origin. Our discovery of numerous additional representatives of preQ1-I and preQ1-II riboswitches supports the hypothesis that this important modified base might have been sensed by ancient RNAs. We have also discovered a third preQ1 riboswitch class called preQ1-III, suggesting that there might be additional rare classes of preQ1riboswitches remaining to be discovered. A plot of the phylogenetic distribution of preQ1- sensing riboswitches reveals which bacterial lineages commonly use these RNAs and which organisms have no known preQ1 sensors. This data might help focus searches for additional preQ1-mediated gene control systems in organisms that have preQ1 metabolic genes but that lack known preQ1-responsive RNA- or protein-based elements.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioinformatics Searches

Homology searches for members and variants of riboswitch classes were conducted using INFERNAL 1.0 and 1.1 on the NCBI Reference Sequence Database release 56 with assorted environmental datasets (Pruitt et al., 2009; McCown et al., 2011; Nawrocki et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2013). Searches were undertaken by increasing the highest accepted E-value in a way similar to that described previously (McCown et al., 2011). Sequences might match to only a part of the riboswitch structure due to a variety of reasons, e.g. the riboswitch is at the edge of a metagenomic contig, an interruption by a transposon insertion, etc. No partial RNA structures were accepted in the final collection of preQ1-I riboswitches. Partial structures were considered for inclusion in the final collection of preQ1-II and preQ1-III riboswitches if the first half of the riboswitch aptamer was present or if the second half was present and it was in a relevant genetic context. For those species without known preQ1-sensing riboswitches, we attempted to find any sequence homology with known preQ1-sensing riboswitches. Specifically, BLAST searches of the 5′ UTRs of yhhQ and queT genes in species lacking preQ1 riboswitch hits were conducted. All consensus models were modelled with R2R (Weinberg and Breaker, 2011).

Phylogenetic Map of PreQ1-sensing Riboswitches

The total collection of preQ1 riboswitch representatives from each type and class were mapped onto a bacterial phylogenetic (Figure 2) tree using the phyla based on the Interactive Tree of Life as provided (Letunic and Bork, 2011).

Chemicals, PCR, and RNA Transcription

PreQ1, preQ0 and N,N-dimethyl-preQ1 were synthesized as previously described (Roth et al., 2007). Guanine, 7-deazaguanine, and 2,6-diaminopurine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All DNAs used to generate templates for in vitro transcription were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. These templates were prepared by PCR via primer extension. A full list of primers and their corresponding full-length constructs can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Each RNA transcription reaction was carried out using double-stranded DNA templates in a 60 μL reaction containing 80 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5 at 23°C), 40 mM DTT, 24 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 4 mM of each ribonucleoside 5′-triphosphate (NTPs), and 40 U bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours and terminated by the addition of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) loading buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 90 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0 at 23°C), and 8 M urea. Transcription products were purified by PAGE on a denaturing (8 M urea) 6% polyacrylamide gel. A band containing the correct size RNA was excised from the gel and the RNA was recovered by soaking the gel slice in a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5 at 23°C), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0 at 23°C). The RNAs were precipitated by adding 50 μL 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.0 at 23°C) and 1 mL of cold (−20°C) ethanol, pelleted by centrifugation, and the resulting pellet washed with cold 70% ethanol, resuspended in water, and stored at −20°C until used.

Generating 5′32P-labeled RNAs

Radioactively labeled RNAs were prepared by dephosphorylating 1 to 5 pmol of the desired RNA using alkaline phosphatase according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche). The dephosphorylated RNAs were 5′-32P labeled by incubation with [γ-32P] ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase following the manufacturer's protocol (New England Biolabs). Denaturing 6% PAGE was used to purify the RNAs as described above, except that a denaturing 10% polyacrylamide gel was necessary for the smaller 84 Sdy RNA.

In-line Probing

In-line probing reactions were carried out essentially as described previously (Regulski and Breaker, 2008). 5′ 32P-labeled RNAs were incubated at 23°C in a solution containing 75 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3 at 23°C), 20 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, and different potential or known ligands at concentrations as indicated for each experiment. After incubation for 40-48 h, the spontaneous cleavage products were separated by denaturing 10% PAGE. The gels were dried and then imaged using a Storm 820 PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare). Band intensities were quantified using ImageQuant 5.1 (GE Healthcare), and those that exhibited the most substantial modulation were used to estimate KD values.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Additional variant types of class I and II preQ1 riboswitches have been discovered.

A third riboswitch class that senses preQ1 has been discovered and validated.

Our findings expand the bacterial lineages that exploit preQ1-sensing riboswitches.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant GM022778 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. P.J.M. was supported in part by NIH Grant T32GM007499. J.J.L. was supported in part by a Yale Science Scholars Fellowship. We thank Dr. M. Plummer for preparing preQ0, preQ1, and dimethyl-preQ1. We thank Dr. J. Barrick (UT-Austin) for assistance with the phylogenetic distribution plot, and we thank Dr. A. Roth, Dr. K. Furukawa, M. Rutenberg-Schoenberg, and other members of the Breaker laboratory for helpful comments. We also thank Dr. J. Wedekind (U. Rochester) for providing insight on preQ1-III riboswitch structure models and we thank R. Bjornson, N. J. Carriero, A. Sherman, and the facilities and staff of the Yale University Faculty of Arts and Sciences High Performance Computing Center (supported by NIH Grant RR19895).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

P.J.M. and R.R.B. designed the experiments, P.J.M., J.J.L., and Z.W. performed the bioinformatics searches, P.J.M. and J.J.L. performed the experiments, and all authors analyzed the data. P.J.M., J.J.L., and R.R.B. wrote the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Data (including additional experimental details), six figures, three supplemental files, and two tables and can be found with this article online.

REFERENCES

- Ames TD, Rodionov DA, Weinberg Z, Breaker RR. A eubacterial riboswitch class that senses the coenzyme tetrahydrofolate. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames TD, Breaker RR. Bacterial riboswitch discovery and analysis. In: Mayer G, editor. The Chemical Biology of Nucleic Acids. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2010. doi: 10.1002/9780470664001.ch20. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick JE, Breaker RR. The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R239. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz M, Kubli E. Wild-type tRNATyrG reads the TMV RNA stop codon, but Q base-modified tRNATyrQ does not. Nature. 1981;294:188–190. doi: 10.1038/294188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker RR. Riboswitches and the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:a003566. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge SW, Daub J, Eberhardt R, Tate J, Barquist L, Nawrocki EP, Eddy SR, Gardner PP, Bateman A. Rfam 11.0: 10 years of RNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:D226–D232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero VC, Toledo VP, Maturana C, Fisher CR, Payne SM, Salazar JC. Expression of Shigella flexneri gluQ-rs gene is linked to dksA and controlled by a transcriptional terminator. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AGY, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. Mechanism for gene control by a natural allosteric group I ribozyme. RNA. 2011;17:1967–1972. doi: 10.1261/rna.2757311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand JMB, Dagberg B, Uhlin BE, Björk GR. Transfer RNA modification, temperature and DNA superhelicity have a common target in the regulatory network of the virulence of Shigella flexneri: the expression of the virF gene. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:924–935. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MS, Katze JR, Trewyn RW. Relationship between a tumor promoter induced decrease in queuine modification of transfer RNA in normal human cells and the expression of an altered cell phenotype. Cancer Res. 1984;44:3215–3219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Walter NG, Brooks CL. Cooperative and directional folding of the preQ1 riboswitch aptamer domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:4196–4199. doi: 10.1021/ja110411m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré-D′Amaré AR. RNA-modifying enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert W. Origin of life: The RNA world. Nature. 1986;319:618. [Google Scholar]

- Granseth E, Daley DO, Rapp M, Melén K, von Heijne G. Experimentally constrained topology models for 51,208 bacterial inner membrane proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene RC. Biosynthesis of methionine. In: Neidhardt FC, editor. Escherichia coli and Salmonella. ASM Press; Washington, DC.: 1996. pp. 542–560. [Google Scholar]

- Holmfeldt K, Solonenko N, Shah M, Corrier K, Riemann L, Verberkmoes NC, Sullivan MB. Twelve previously unknown phage genera are ubiquitous in global oceans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12798–12803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305956110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkin TM. Riboswitch RNAs: using RNA to sense cellular metabolism. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3383–3390. doi: 10.1101/gad.1747308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata-Reuyl D. An embarrassment of riches: the enzymology of RNA modification. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JL, Krucinska J, McCarty RM, Bandarian V, Wedekind JE. Comparison of a preQ1 riboswitch aptamer in metabolite-bound and free states with implications for gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:24626–24637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, Paulin L, Säde E, Salovuori N, Alatalo ER, Björkroth KJ, Auvinen P. Genome sequence of a food spoilage lactic acid bacterium, Leuconostoc gasicomitatum LMG 18811T, in association with specific spoilage reactions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:4344–4351. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00102-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Peterson R, Feigon J. Structural insights into riboswitch control of the biosynthesis of queuosine, a modified nucleotide found in the anticodon of tRNA. Mol. Cell. 2009;33:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Peterson R, Feigon J. Erratum: Structural insights into riboswitch control of the biosynthesis of queuosine, a modified nucleotide found in the anticodon of tRNA. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:653–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JN, Roth A, Breaker RR. Guanine riboswitch variants from Mesoplasma florum selectively recognize 2′-deoxyguanosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:16092–16097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705884104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DJ, Edwards TE, Ferré-D'Amaré AR. Cocrystal structure of a class I preQ1 riboswitch reveals a pseudoknot recognizing an essential hypermodified nucleobase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:343–344. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ER, Baker JL, Weinberg Z, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. An allosteric self-splicing ribozyme triggered by a bacterial secondary messenger. Science. 2010;329:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1190713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life v2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W475–478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman JA, Salim M, Krucinska J, Wedekind JE. Structure of a class II preQ1 riboswitch reveals ligand recognition by a new fold. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:353–355. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti M, Capela D, Poincloux R, Benmeradi N, Auriac MC, Le Ru A, Maridonneau-Parini I, Batut J, Masson-Boivin C. Queuosine biosynthesis is required for Sinorhizobium meliloti-induced cytoskeletal modifications on HeLa Cells and symbiosis with Medicago truncatula. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Breaker RR. Adenine riboswitches and gene activation by disruption of a transcription terminator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown PJ, Roth A, Breaker RR. An expanded collection and refined consensus model of glmS ribozymes. RNA. 2011;17:728–736. doi: 10.1261/rna.2590811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier F, Suter B, Grosjean H, Keith G, Kubli E. Queuosine modification of the wobble base in tRNAHis influences ‘in vivo’ decoding properties. EMBO J. 1985;4:823–827. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, Roth A, Chervin SM, Garcia GA, Breaker RR. Confirmation of a second natural preQ1 aptamer class in Streptococcaceae bacteria. RNA. 2008;14:685–695. doi: 10.1261/rna.937308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange R, Batey RT. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki EP, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2933–2935. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JW, Sudarsan N, Furukawa K, Weinberg Z, Wang JX, Breaker RR. Riboswitches in eubacteria that sense the second messenger c-di-AMP. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:834–839. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A, Kirino Y, Ikeuchi Y, Tsutomu S. Biosynthesis of wybutosine, a hyper-modified nucleoside in eukaryotic phenylalanine tRNA. EMBO J. 2006;25:2142–2154. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak C, Jaiswal YK, Vinayak M. Modulation in the activity of lactate dehydrogenase and level of c-Myc and c-Fos by modified base queuine in cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008;7:85–91. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.1.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrone PM, Dewhurst J, Tommasi R, Whitehead L, Pomerantz AK. Atomic-scale characterization of conformational changes in the preQ1 riboswitch aptamer upon ligand binding. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2011;30:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleij CW. Pseudoknots: a new motif in the RNA game. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990;15:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90214-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Klimke W, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences: current status, policy and new initiatives. Nucl. Acids Res. 2009;37:D32–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakovich T, Boland C, Bernstein I, Chikwana VM, Iwata-Reuyl D, Kelly VP. Queuosine deficiency in eukaryotes compromises tyrosine production through increased tetrahydrobiopterin oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:19354–19363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh A, Winkler WC. Magnesium-sensing riboswitches in bacteria. RNA Biol. 2010;7:77–83. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.1.10490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski EE, Breaker RR. In-line probing analysis of riboswitches. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;419:53–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-033-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Winkler WC, Regulski EE, Lee BW, Lim J, Jona I, Barrick JE, Ritwik A, Kim JN, Welz R, Iwata-Reuyl D, Breaker RR. A riboswitch selective for the queuosine precursor preQ1 contains an unusually small aptamer domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri M, Häuser R, Ouellette M, Dehbi M, Moeck G, García E, Titz B, Uetz P, Moineau S. Genome annotation and intraviral interactome for the Streptococcus pneumoniae virulent phage Dp-1. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:551–562. doi: 10.1128/JB.01117-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serganov A, Nudler E. A decade of riboswitches. Cell. 2013;152:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA. 1999;5:1308–1325. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulière MF, Altman RB, Schwarz V, Haller A, Blanchard SC, Micura R. Tuning a riboswitch response through structural extension of a pseudoknot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E3256–E3264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304585110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan N, Hammond MC, Block KF, Welz R, Barrick JE, Roth A, Breaker RR. Tandem riboswitch architectures exhibit complex gene control functions. Science. 2006;314:300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1130716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan N, Lee ER, Weinberg Z, Moy RH, Kim JN, Link KH, Breaker RR. Riboswitches in eubacteria that sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2008;321:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1159519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbonavicius J, Qian Q, Durand JM, Hagervall TG, Björk GR. Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J. 2001;20:4863–4873. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JX, Breaker RR. Riboswitches that sense S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;86:157–168. doi: 10.1139/O08-008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z, Breaker RR. R2R--software to speed the depiction of aesthetic consensus RNA secondary structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z, Wang JX, Bogue J, Yang J, Corbino K, Moy RH, Breaker RR. Comparative genomics reveals 104 candidate structured RNAs from bacteria, archaea, and their metagenomes. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.