Abstract

The optic nerve often suffers regenerative failure after injury, leading to serious visual impairment such as glaucoma. The main inhibitory factors, including Nogo-A, oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein, and myelin-associated glycoprotein, exert their inhibitory effects on axonal growth through the same receptor, the Nogo-66 receptor (NgR). Oncomodulin (OM), a calcium-binding protein with a molecular weight of an ∼12 kDa, which is secreted from activated macrophages, has been demonstrated to have high and specific affinity for retinal ganglion cells (RGC) and promote greater axonal regeneration than other known polypeptide growth factors. Protamine has been reported to effectively deliver small interference RNA (siRNA) into cells. Accordingly, a fusion protein of OM and truncated protamine (tp) may be used as a vehicle for the delivery of NgR siRNA into RGC for gene therapy. To test this hypothesis, we constructed OM and tp fusion protein (OM/tp) expression vectors. Using the indirect immunofluorescence labeling method, OM/tp fusion proteins were found to have a high affinity for RGC. The gel shift assay showed that the OM/tp fusion proteins retained the capacity to bind to DNA. Using OM/tp fusion proteins as a delivery tool, the siRNA of NgR was effectively transfected into cells and significantly down-regulated NgR expression levels. More importantly, OM/tp-NgR siRNA dramatically promoted axonal growth of RGC compared with the application of OM/tp recombinant protein or NgR siRNA alone in vitro. In addition, OM/tp-NgR siRNA highly elevated intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels and inhibited activation of the Ras homolog gene family, member A (RhoA). Taken together, our data demonstrated that the recombinant OM/tp fusion proteins retained the functions of both OM and tp, and that OM/tp-NgR siRNA might potentially be used for the treatment of optic nerve injury.

Keywords: axon regeneration, Nogo-66 receptor, oncomodulin, retinal ganglion cells

INTRODUCTION

The optic nerve, composed of axons from retinal ganglion cells (RGC), often suffers regenerative failure after injury, leading to serious visual impairment (Frade et al., 1999). However, there is still a lack of effective methods for clinical treatment. The optic nerve belongs to the central nervous system (CNS) and the major obstacles to the regeneration of CNS neurons are a deficiency of neurotropic factors and the enrichment of myelin-associated inhibitory molecules (Spencer and Filbin, 2004). Unlike the peripheral nervous system, myelin of the CNS is made up of oligodendroglial cells, which mainly secrete neuronal growth inhibitors and inhibit the axonal growth of the CNS (Schachner, 1994).

After CNS injury, neurons are in an extracellular environment full of inhibitory factors. To date, three myelin-associated inhibitory molecules of the CNS have been characterized: Nogo-A (Chen et al., 2000; GrandPre et al., 2000), oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (Pham-Dinh et al., 1994), and myelin-associated glycoprotein (McKerracher et al., 1994; Mukhopadhyay et al., 1994); all of these exert their effects through the same receptor, the Nogo-66 receptor (NgR) (Wang et al., 2002a). A previous study has demonstrated that inhibiting the function of NgR by an antagonist peptide relieves endogenous inhibitory activity and promotes axonal growth, implying that NgR plays a central role in the inhibition of axon regeneration in the CNS after injury (GrandPre et al., 2002). Disturbing the intravitreal environment has been found to activate RGC to regenerate axonal growth (Berry et al., 1996; Fischer et al., 2001; Leon et al., 2000; Lorber et al., 2005), which has been suggested to be associated with macrophage activation (Yin et al., 2003). It is intriguing that proteins secreted by macrophages show a potent effect on axon regeneration and that this effect is enhanced by elevating intra-cellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels (Li et al., 2003). Later, it was demonstrated that among macrophage-derived factors, oncomodulin (OM) is the principal mediator of optic nerve regeneration (Yin et al., 2006). OM is a calcium-binding protein of 108 amino acids, with a molecular mass of 11.7 kDa (MacManus et al., 1983). OM was originally identified in hepatocellular carcinoma of the rat in the late 1970s, and was also found to be expressed in rat fibrosarcoma and mouse sarcoma (MacManus, 1979). OM has been reported to have a low expression level in the retina, but is highly expressed upon stimulation of inflammation (Berry et al, 1996). OM shows high and specific affinity for its receptor on RGC (Meyer-Franke et al., 1998).

In the present study, we speculated that OM activation combined with the inhibition of neuron inhibitory signals might show a more potent stimulatory effect on axonal growth. Truncated protamine (tp), a short type of protamine consisting of 22 amino acids, contains many basic amino acids and is capable of binding to nucleic acids (Inoh et al., 2013). Thus, we introduced tp as an agent for the delivery of OM protein and NgR small interference RNA (siRNA). The direct effect of OM/tp-NgR siRNA on axonal growth in RGC was investigated in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Eight-week-old Fisher 344 rats (Vital River, China) were housed in clean polypropylene cages at a controlled temperature of 22 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 55 ± 5% with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. The rats had free access to food and water throughout the study. All experimental animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fourth Military University (China). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

Isolation and culture of rat macrophages

Rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg; Merck KGaA, Germany). Peritoneal macrophages were obtained by sterile lavage of the abdomen of the rats with Hanks’ balanced salt solution. The lavage fluid was removed from the abdomen and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 8 min. The supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet was collected. Cells were resuspended in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Cloning, expression, and identification of OM/tp recombinant proteins

Macrophages were treated with zymosan (1.25 mg/ml; Sangon, China) and incubated for 8 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Thereafter, total RNA of macrophages was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and 5 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Clontech, USA). The cDNAs were used as templates for cloning of the OM gene. The OM gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the OM forward primer (5′-ATAGGATCCATGAGCATCACGGACATCCTGAGC G-3′) and OM reverse primer (5′-CCGAAGCTTCGAGAGTGCA CCATTTCCTGGAATTCA-3′), which contained NdeI and XhoI restriction sites, respectively. The DNA fragments of OM were obtained and verified by gene sequencing (BGI, China). Subsequently, the purified OM DNA fragments were used as templates for cloning of OM/tp using the OM/tp forward primer (5′-ATAGGATCCATGAGCATCACGGACATCCTGAGCG-3′) and reverse primer (5′-CTAAAGCTTAATGCTCCGCC TCCTTCGT-CTGCGACTCTTTGTCTCTGGCGGTAATATCTGCTCCGGCTCTGGCTGCGAAGTGCACCATTTCCTGGAATTCA-3′; the sequence for tp is underlined), containing NdeI and XhoI restriction sites, respectively. The fragments were obtained and the sequences were verified, and then subcloned into pET30a plasmid to generate the recombinant plasmid pET30a-OM/tp with restriction sites.

The recombinant plasmid pET30a-OM/tp was introduced into Escherichia coli Rosetta host cells. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (0.1 mM IPTG; Sangon, China) was added and incubated for 6 h at 35°C to induce target protein expression. Afterwards, bacteria were harvested and lysed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.2% Triton X-100. The complexes were sonicated, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant, containing recombinant proteins, was collected and the fusion proteins were purified using His-Bind resin (Ni2+-resin; Novagen, Germany) according to standard protocols. The purified proteins were analyzed by 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and further verified by Western blot analysis using 6×His rabbit monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, USA).

Isolation and culture of rat primary RGC

Rat RGC were isolated and cultured from rats, as previously reported (Barres et al., 1988; Winzeler and Wang, 2013) with some modifications. Briefly, neonatal rats at postnatal days 2–3 were euthanized and disinfected in alcohol (75%). The approximate retinas were separated from the enucleated eyeballs and treated with papain followed by dissociated into a single cell suspension. Non-neuronal cells including endothelial cells, macrophages and microglia, and were depleted by using Bandeira simplifolica lectin I and/or anti-macrophage antibody coated-dishes. RGC were positively purified by using anti-Thy-1 antibodies coated-dishes. Then, the Thy-1 positive RGC were collected and cultured in DMEM containing trypsin (0.25%) for 30 min. After digestion, the RGC were washed three times with DMEM and then transferred into fresh medium containing B27 supplement (1:50; Invitrogen, USA) and penicillin/streptomycin (0.2 mg/ml), and maintained at 5% CO2 at 37°C in an incubator.

Flow cytometry assay

The 6× His monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was dialyzed three times with crosslinking reaction solution (0.05 mM NaHCO3) at 4°C. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide to a concentration of 1 mg/ml and gently added to the mAb solution at the ratio of 1 mg:150 μg before being incubated for 8 h at 4°C in the dark. Then, FITC-conjugated mAbs were dialyzed and purified by Sephadex G-50 (Seebio, China). A total of 100 mg OM/tp fusion protein was added and incubated with RGC for 12 h. Thereafter, cells were collected and washed three times in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in PBS. FITC-conjugated mAbs were added and incubated with RGC for 20 min, followed by two washes with ice-cold PBS. Then, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry assay.

Gel shift assay

The plasmid pET30a (1 μg) was mixed with different amounts of OM/tp fusion protein (0, 2, 4, and 8 μg) in NaCl solution (0.2 M) at room temperature for 30 min. Thereafter, the mobility of the OM-tp-DNA complex was analyzed by electrophoresis on agarose gels (1%).

Preparation of OM/tp-siRNA

According to the gene sequence of rat NgR, two siRNA targeting NgR (NgR-1 siRNA, sense: 3′-AUUUCCAACAGACGCCGGCCU-5′ and antisense: 3′-GCCGGCGUCUGUUGGAAAUGC-5′; NgR-2 siRNA, sense: 3′-AACAACCUGGCCUCCUGCGGG-5′ and antisense: 3′-CGCAGGAGGCCAGGUUGUUCC-5′) were designed. Meanwhile, nonspecific sequences (sense: 3′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUUU-5′ and antisense: 3’-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAAUU-5′) were used as a control. The siRNA was synthesized by Shanghai GenePharma Co. Ltd (China). To prepare OM/tp-siRNA, the siRNA and fusion proteins were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:6 (Wen et al., 2007) in 500 μl of DMEM and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the mixture was added to the RGC and incubated for the indicated times.

Neurite outgrowth assays

RGC were fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%) and stained with growth-associated protein 43 (GAP-43) mAbs. Neurite outgrowth was measured in images taken by the Olympus FV300 laser scanning confocal microscope (Japan). Approximately 60 cells were randomly selected in each group and the average axon length of the cells was measured using the Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., USA). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments.

Western blot analysis

A total of 20 μg protein was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE followed by electro-blotting onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, UK). Then, the membrane was incubated with 2% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline to block nonspecific binding at room temperature for 1 h. Next, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit monoclonal RhoA antibody (1:500), Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA; rabbit polyclonal NgR antibody (1:600), Abcam, UK; 6× His rabbit monoclonal antibody (1:800), Cell Signaling Technology) and diluted in the blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Boster Corporation, China) diluted 1:1000 in the blocking buffer for 1 h. Finally, the HRP substrate 4-chloro-1-naphthol (4-CN) was used for protein visualization.

Measurements of active RhoA and cAMP levels

The activity of RhoA was measured according to a previously described method (Noren et al., 2000). Briefly, cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Then, cells were lysed in Buffer A, containing Tris (50 mM, pH 7.6), NaCl (500 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM), orthovanadate (100 μM), deoxycholate (0.5%), Triton X-100 (1%), and SDS (0.1%), supplemented with protease inhibitors (100 μM). After centrifugation, supernatants were collected and divided into two equal samples. One sample was incubated with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Rho-binding domain (RBD) beads followed by washing three times with ice-cold Buffer B containing Tris (50 mM, pH 7.6), NaCl (150 mM), MgCl2 (0.5 mM), orthovanadate (100 μM), and Triton X-100 (1%), supplemented with protease inhibitors. The bound fraction, containing active GTP-RhoA, was collected for further analysis. The other sample of whole cell lysate, with an equal volume, was used for total RhoA analysis. Protein levels of total RhoA and active RhoA were analyzed by Western blotting. Intracellular cAMP levels were assessed by an EIA cAMP ELISA kit (Assay Designs, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups and among multiple groups were performed by Student t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), respectively. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., USA).

RESULTS

Expression and characterization of OM/tp fusion protein

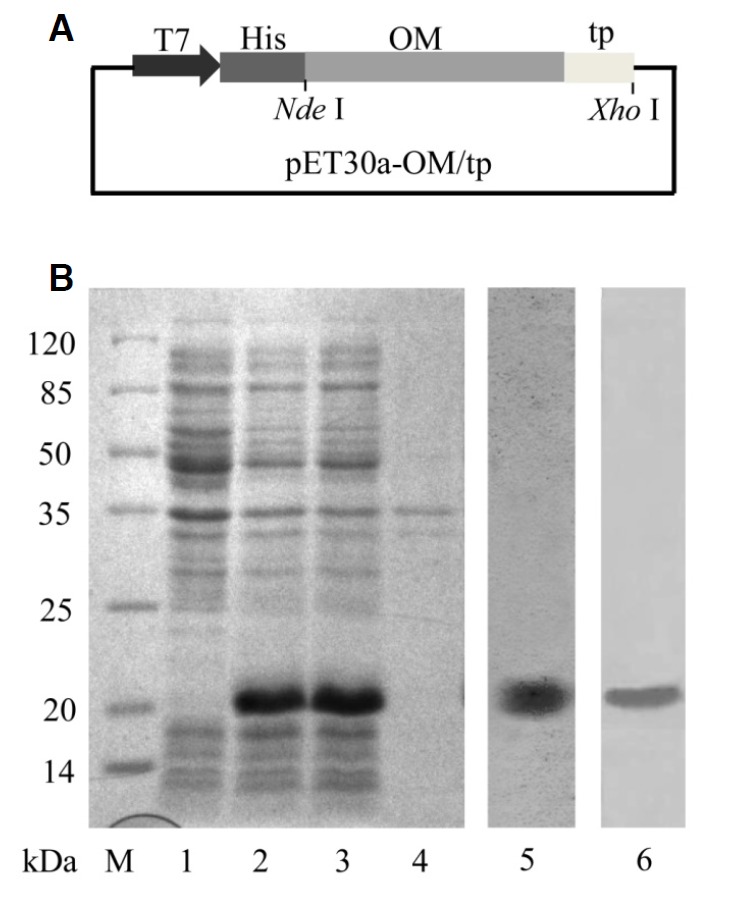

To generate recombinant OM/tp proteins, the DNA fragment of OM/tp was amplified and subcloned into pET30a plasmid with NdeI and XhoI restriction sites to obtain pET30a recombinant plasmid (Fig. 1A). The pET30a-OM/tp recombinant plasmids were then transformed into E. coli Rosetta host cells, and the expression of recombinant OM/tp proteins was induced by IPTG. As expected, the results showed that OM/tp fusion proteins had an approximate molecular mass of 21 kDa and were mainly present in the supernatants (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–4). The OM/tp fusion proteins were further purified by Ni2+-resin affinity chromatography and were detected by anti-6× His antibody (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 6). These results indicated that OM/tp fusion proteins were successfully generated in a soluble expression manner.

Fig. 1.

Expression and characterization of OM/tp fusion protein. (A) Schematic structure of pET30a-OM/tp recombinant plasmid. (B) SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of OM/tp recombinant protein. M, protein markers; lane 1, total bacterial protein without induction; lane 2, total bacterial protein after induction by IPTG (0.1 mM); lane 3, the supernatant from IPTG-induced total bacterial protein; lane 4, lysates of inclusion bodies from IPTG-induced total bacterial protein; lane 5, purified OM/tp recombinant protein; lane 6, Western blot analysis of purified OM/tp recombinant protein.

Recombinant OM/tp protein highly binds to RGC

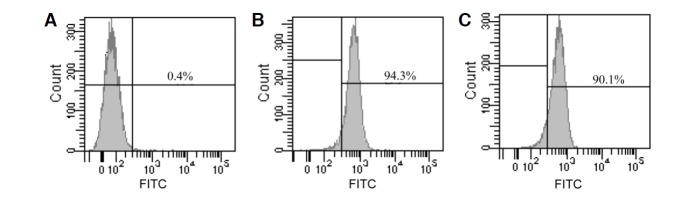

To determine whether the recombinant OM/tp retained the capacity to target RGC, RGC were treated with OM/tp fusion protein. FITC-conjugated 6× His mAbs were added to the cells and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. Compared with the control group treated with PBS, which showed 0.4% positive cells (Fig. 2A), the cells treated with His-tagged recombinant OM showed 94.3% positive cells (Fig. 2B). Similarly, recombinant OM/tp-treated cells showed 90.1% positive cells (Fig. 2C). The data implied that the OM/tp fusion protein retained the capacity of the OM protein to bind to RGC through a cell surface receptor.

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometry assay to determine the binding capacity of OM/tp to RGC. Cells were treated with PBS (A), recombinant OM (B), or recombinant OM/tp (C). FITC-conjugated 6× His mAbs were added and the fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry assay.

OM/tp-NgR siRNA significantly knocks-down NgR expression in RGC

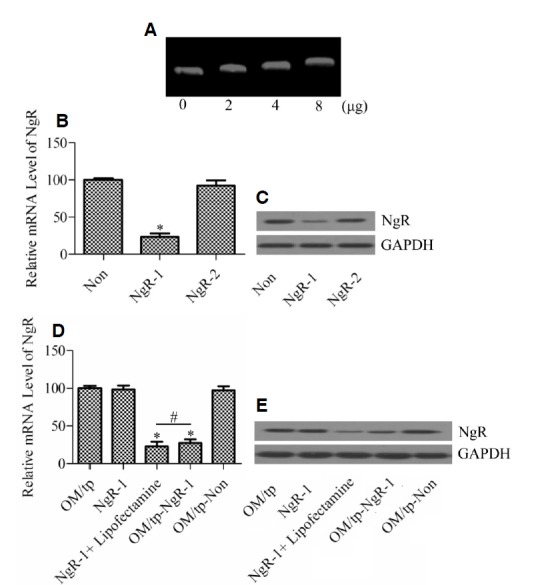

Protamine is capable of binding to DNA and carrying DNA through the cell membrane into to the cell interior (Junghans et al., 2000). To investigate whether the generated recombinant OM/tp could bind to DNA, pET30a plasmid was mixed with different amounts (0, 2, 4, and 8 μg) of OM/tp, and the mobility was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The results showed that plasmid DNA mixed with OM/tp moved slowly in a dose-dependent manner, implying the formation of a DNA/OM/tp complex (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Assessment of efficiency of OM/tp in delivering nucleic acid. (A) The DNA-binding ability of recombinant OM/tp was determined by gel shift assay. Different amounts (0, 2, 4, and 8 μg) of OM/tp were incubated with pET30a plasmid (1 μg) for 30 min and then the mixtures were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. qRT-PCR (B) and Western blotting (C) were used to analyze the knockdown efficiency of NgR-1 and NgR-2 siRNA. Nonspecific siRNA (Non) was used as control. *P < 0.05 vs Non or NgR-2 siRNA group. qRT-PCR (D) and Western blot (E) were used to analyze the capacity of OM/tp to deliver siRNA to the target gene. Cells were treated with recombinant OM/tp, NgR-1 siRNA without lipofectamine, NgR-1 siRNA mixed with lipofectamine, OM/tp-NgR-1 siRNA, and OM/tp-nonspecific siRNA, respectively. *p < 0.05 vs OM/tp, NgR-1, and OM/tp-Non groups. #p > 0.05 denotes no significant difference.

Next, we synthesized two siRNA, NgR-1 and NgR-2, which targeted the NgR gene sequence. NgR-1 and NgR-2 siRNA were then transfected into RGC to determine their knockdown efficiency. Compared with nonspecific siRNA-treated cells, NgR-1 siRNA-treated cells showed a significant decrease of NgR mRNA (Fig. 3B). The decrease of NgR protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3C). However, NgR-2 siRNA had no effect on NgR expression. The data verified that NgR-1 siRNA specifically targeted the NgR gene.

To further determine whether OM/tp carrying siRNA was capable of passing through the cell membrane to knockdown the target gene, recombinant OM/tp was mixed with siRNA, and was then transfected into cells. The results showed that NgR mRNA expression was significantly decreased in the NgR-1 siRNA mixed with lipofectamine group and OM/tp-NgR-1 siRNA group compared with the OM/tp group, NgR-1 siRNA without lipofectamine group, and OM/tp-nonspecific siRNA group (Fig. 3D). There was no significant difference between the NgR-1 siRNA with lipofectamine group and the OM/tp-NgR-1 siRNA group, implying that OM/tp was an efficient agent for siRNA delivery. These results were further confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3E).

OM/tp-NgR siRNA significantly promotes axonal growth in RGC

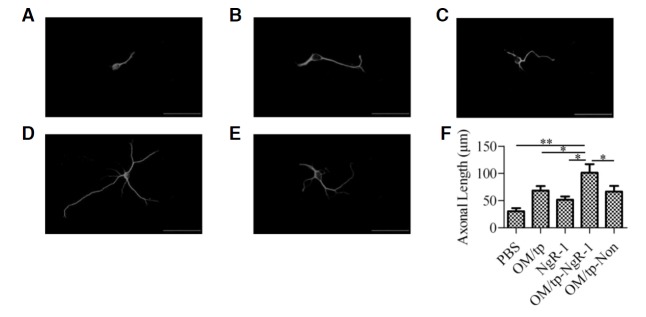

To investigate whether OM/tp-NgR siRNA was able to stimulate RGC to extend axons in culture, RGC were pre-incubated with forskolin and then treated with OM/tp, NgR siRNA, OM/tp-NgR siRNA, and OM/tp-nonspecific siRNA. Three days later, the length of the axons was measured. Compared with the control group, which was treated with PBS (30.52 ± 5.48 μm), the average axonal length was longer in cells treated with OM/tp recombinant proteins (68.27 ± 8.36 μm) and in cells treated with NgR siRNA without OM/tp recombinant proteins (51.35 ± 6.41 μm). As expected, in the OM/tp-NgR siRNA-treated group, RGC showed a potent increase in the average axonal length (101.38 ± 15.70 μm) compared with the control group (p < 0.01), OM/tp group (p < 0.05), and NgR siRNA group (p < 0.05). However, RGC treated with OM/tp-nonspecific siRNA showed an average axonal length of 66.56 ± 10.45 μm, which was similar to that of the OM/tp recombinant group but shorter than that of the OM/tp-NgR siRNA group (p < 0.05). The data demonstrated that OM/tp-NgR siRNA had a potent stimulatory effect on axonal growth in RGC (Figs. 4A–4F).

Fig. 4.

Effect of OM/tp-NgR siRNA on axon regeneration of RGC. RGC were pre-incubated with forskolin (100 μM) for 6 h. Then the cells were treated with PBS (A), OM/tp (B), NgR siRNA (C), OM/tp-NgR siRNA (D), or OM/tp-nonspecific siRNA (E) and incubated for 72 h. Cells were immunostained with GAP-43 antibody and observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy. (F) The average axon length of the cells was measured by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

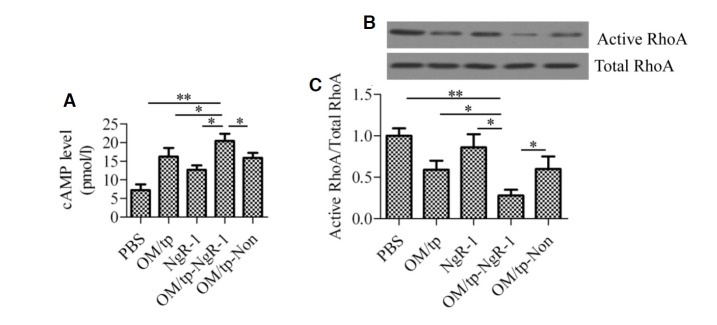

OM/tp-NgR siRNA markedly increases axon regeneration signals

To further explore the effect of OM/tp-NgR siRNA on axon regeneration signals, we first measured the changes in intra-cellular cAMP levels upon treatment with OM/tp, NgR siRNA, OM/tp-NgR siRNA, and OM/tp-nonspecific siRNA. Intracellular cAMP levels were increased in OM/tp- and NgR siRNA-treated groups, which were 16.25 ± 1.32 pmol/L and 12.68 ± 1.17 pmol/L, respectively, compared with the levels in the control group (7.24 ± 1.52 pmol/L). The OM/tp-NgR siRNA-treated group showed higher levels of cAMP (20.43 ± 1.91 pmol/L) compared with the control group (p < 0.01), OM/tp group (p < 0.05), and NgR siRNA group (p < 0.05). However, the OM/tpnonspecific siRNA-treated group showed lower levels of cAMP (15.86 ± 1.86 pmol/L) than the OM/tp-NgR siRNA-treated group (Fig. 5A). Next, we assessed the activity of RhoA. Similarly, the activation of RhoA was significantly inhibited in the OM/tp-NgR siRNA group compared with the other groups (Figs. 5B and 5C).

Fig. 5.

Effect of OM/tp-NgR siRNA on axon regeneration signals. (A) Detection of intracellular levels of cAMP. (B) Measurement of active RhoA and total RhoA by Western blot analysis (C). Protein levels were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software and relative RhoA activity is presented as active RhoA normalized to total RhoA. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Here, we studied for the first time the effect of tp carrying OM and NgR siRNA on axonal growth in RGC. We found that OM/tp-NgR siRNA efficiently promoted axonal growth in RGC in vitro. OM had a stimulatory effect on axonal growth and NgR siRNA-mediated NgR gene silencing blocked the transduction of inhibitory signals.

By expressing recombinant DNA, we successfully obtained a fusion protein of OM/tp. We then showed that the OM/tp recombinant protein retained the capacity of OM protein to bind to RGC through a cell surface receptor. Yin et al. (2006) described that the OM protein binds strongly to RGC in the presence of elevated intracellular cAMP stimulated by forskolin. They further suggested that OM shows high affinity and specific binding to RGC, which are cAMP-dependent. However, the receptor for OM has not been identified to date. It has been proposed that cAMP induces the receptor to translocate from the cytosol to the cell surface, which is necessary for OM binding (Meyer-Franke et al., 1998).

Protamine is now taken as an ideal agent for the delivery of DNA into cells, as it can condense DNA into compact particles, accelerating DNA uptake and increasing transfection efficiency (You et al., 1999). Furthermore, protamine is also capable of binding to siRNA to form a protein/siRNA complex, delivering siRNA into various types of cells. Additionally, the protamine-based systemic delivery is now considered to be a safe and reliable method for siRNA delivery (Choi et al., 2010; Peer et al., 2007). Here, we found that OM/tp recombinant protein carrying NgR siRNA efficiently silenced NgR gene expression in RGC. The data suggest that our OM/tp fusion proteins not only bound to RGC with high affinity, but were also capable of delivering siRNA to knockdown the target gene. To further investigate the application of OM/tp-NgR siRNA as an effective drug for axon regeneration, we evaluated the effect of OM/tp-NgR siRNA on RGC in vitro. Because forskolin promoted interaction of OM with its receptor (Yin et al., 2006), we pretreated RGC with forskolin and then added OM/tp-NgR siRNA to investigate its effect on axonal growth. The results showed that OM/tp-NgR siRNA significantly increased the average length of axons compared with the application of OM/tp recombinant protein or NgR siRNA alone. These results implied that OM/tp-NgR siRNA had a potent stimulatory effect on axonal growth in RGC.

Most recently, neutrophils, the first responders of the innate immune system, were demonstrated to express OM and markedly stimulate optic nerve regeneration (Kurimoto et al., 2013). The data further implied that OM plays an important role in axonal growth. However, the mechanism underlying the regulation of neuronal growth and regeneration by OM remains poorly understood. Yin et al. (2006) proposed that the effect of OM in promoting greater axon outgrowth is associated with a calmodulin-dependent kinase II-dependent pathway. Neurotrophic factors overcome the inhibitory effects of myelin by elevating cAMP levels (Fischer et al., 2004). It is reported that OM exerts its effects in a cAMP-dependent manner and can further elevate intracellular cAMP levels (Yin et al., 2006).

Inhibitory signals transduced into cells through NgR activates RhoA, which causes myosin depolymerization and growth cone collapse, and ultimately leads to axon regeneration failure [15]. Thus, blocking the interaction of NgR with inhibitory molecules can suppress the activation of RhoA. Also, disrupting the interaction of NgR with the p75 receptor complex blocked the transduction of inhibitory signals into the interior of responding neurons (Wang et al., 2002b). These reports suggest that NgR plays a central role in the regulation of inhibitory signal transduction. Intracellular cAMP has been suggested to activate protein kinase A, which induces the phosphorylation and inactivation of RhoA (Ellezam et al., 2002). Here, we found that OM activation combined with NgR knockdown significantly elevated cAMP levels and inhibited RhoA activation in RGC compared with the application of OM/tp recombinant protein or NgR siRNA alone.

Nogo-A, one of the myelin-associated inhibitory factors which directly interacts with NgR, is also found in the central and peripheral neurons during development (Caroni and Schwab, 1988; Chen et al., 2000). Nogo-A is also expressed in the neonatal rat visual system during development (Huo et al., 2011). Huo et al. (2013) demonstrated that Nogo-A was highly expressed in RGC in which knockdown of Nogo-A by siRNA significantly promoted axonal length of RGC. Therefore, the ligands of NgR such as Nogo-A can be expressed in RGC and may exert an inhibitory effect on axonal growth through NgR. Accordingly, we demonstrated that the knockdown of NgR alone by siRNA promoted axonal growth of RGC. OM exerted its effect by interacting with its receptor on RGC to promote axonal growth. In addition, NgR siRNA specifically inhibited the transduction of inhibitory signals. Taken together, OM/tp-NgR siRNA dramatically promoted axonal growth in RGC. It appears that OM combined with NgR knockdown can enhance the stimulatory effect on axonal growth. Thus, the OM/tp-NgR siRNA designed provided novel insight for the potential of gene therapy of optic nerve injury. As OM/tp-NgR siRNA might potentially be used for clinical therapy, we are interested in further evaluating its safety and biological activity in vivo. Further investigation of OM/tp-NgR siRNA in animal models will be carried out in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30700930).

REFERENCES

- Barres B.A., Silverstein B.E., Corey D.P., Chun L.L. Immunological, morphological, and electrophysiological variation among retinal ganglion cells purified by panning. Neuron. 1988;1:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M., Carlile J., Hunter A. Peripheral nerve explants grafted into the vitreous body of the eye promote the regeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons severed in the optic nerve. J. Neurocytol. 1996;25:147–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02284793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P., Schwab M.E. Antibody against myelin-associated inhibitor of neurite growth neutralizes nonpermissive substrate properties of CNS white matter. Neuron. 1988;1:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.S., Huber A.B., van der Haar M.E., Frank M., Schnell L., Spillmann A.A., Christ F., Schwab M.E. Nogo-A is a myelin-associated neurite outgrowth inhibitor and an antigen for monoclonal antibody IN-1. Nature. 2000;403:434–439. doi: 10.1038/35000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y.S., Lee J.Y., Suh J.S., Kwon Y.M., Lee S.J., Chung J.K., Lee D.S., Yang V.C., Chung C.P., Park Y.J. The systemic delivery of siRNAs by a cell penetrating peptide, low molecular weight protamine. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1429–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellezam B., Dubreuil C., Winton M., Loy L., Dergham P., Selles-Navarro I., McKerracher L. Inactivation of intracellular Rho to stimulate axon growth and regeneration. Prog. Brain Res. 2002;137:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D., Heiduschka P., Thanos S. Lens-injury-stimulated axonal regeneration throughout the optic pathway of adult rats. Exp. Neurol. 2001;172:257–272. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer D., Petkova V., Thanos S., Benowitz L.I. Switching mature retinal ganglion cells to a robust growth state in vivo: gene expression and synergy with RhoA inactivation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8726–8740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2774-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frade J.M., Bovolenta P., Rodriguez-Tebar A. Neurotrophins and other growth factors in the generation of retinal neurons. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999;45:243–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990515/01)45:4/5<243::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GrandPre T., Nakamura F., Vartanian T., Strittmatter S.M. Identification of the Nogo inhibitor of axon regeneration as a Reticulon protein. Nature. 2000;403:439–444. doi: 10.1038/35000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GrandPre T., Li S., Strittmatter S.M. Nogo-66 receptor antagonist peptide promotes axonal regeneration. Nature. 2002;417:547–551. doi: 10.1038/417547a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y., Yuan R.D., Ye J., Yin X.L., Zou H. Expression of Nogo-A and Nogo receptor in neonatal rats visual system during development. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2011;47:54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y., Yin X.L., Ji S.X., Zou H., Lang M., Zheng Z., Cai X.F., Liu W., Chen C.L., Zhou Y.G., et al. Inhibition of retinal ganglion cell axonal outgrowth through the Amino-Nogo-A signaling pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2013;38:1365–1374. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoh Y., Furuno T., Hirashima N., Kitamoto D., Nakanishi M. Synergistic effect of a biosurfactant and protamine on gene transfection efficiency. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;49:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junghans M., Kreuter J., Zimmer A. Antisense delivery using protamine-oligonucleotide particles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E45. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurimoto T., Yin Y., Habboub G., Gilbert H.Y., Li Y., Nakao S., Hafezi-Moghadam A., Benowitz L.I. Neutrophils express oncomodulin and promote optic nerve regeneration. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:14816–14824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5511-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon S., Yin Y., Nguyen J., Irwin N., Benowitz L.I. Lens injury stimulates axon regeneration in the mature rat optic nerve. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4615–4626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04615.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Irwin N., Yin Y., Lanser M., Benowitz L.I. Axon regeneration in goldfish and rat retinal ganglion cells: differential responsiveness to carbohydrates and cAMP. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:7830–7838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber B., Berry M., Logan A. Lens injury stimulates adult mouse retinal ganglion cell axon regeneration via both macrophage- and lens-derived factors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;21:2029–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacManus J.P. Occurrence of a low-molecular-weight calcium-binding protein in neoplastic liver. Cancer Res. 1979;39:3000–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacManus J.P., Watson D.C., Yaguchi M. The complete amino acid sequence of oncomodulin--a parvalbumin-like calcium-binding protein from Morris hepatoma 5123tc. Eur. J. Biochem. 1983;136:9–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerracher L., David S., Jackson D.L., Kottis V., Dunn R.J., Braun P.E. Identification of myelin-associated glycoprotein as a major myelin-derived inhibitor of neurite growth. Neuron. 1994;13:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Franke A., Wilkinson G.A., Kruttgen A., Hu M., Munro E., Hanson M.G., Jr., Reichardt L.F., Barres B.A. Depolarization and cAMP elevation rapidly recruit TrkB to the plasma membrane of CNS neurons. Neuron. 1998;21:681–693. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80586-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay G., Doherty P., Walsh F.S., Crocker P.R., Filbin M.T. A novel role for myelin-associated glycoprotein as an inhibitor of axonal regeneration. Neuron. 1994;13:757–767. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren N.K., Liu B.P., Burridge K., Kreft B. p120 catenin regulates the actin cytoskeleton via Rho family GTPases. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:567–580. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer D., Zhu P., Carman C.V., Lieberman J., Shimaoka M. Selective gene silencing in activated leukocytes by targeting siRNAs to the integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4095–4100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608491104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham-Dinh D., Allinquant B., Ruberg M., Della Gaspera B., Nussbaum J.L., Dautigny A. Characterization and expression of the cDNA coding for the human myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:2353–2356. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachner M. Neural recognition molecules in disease and regeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1994;4:726–734. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T., Filbin M.T. A role for cAMP in regeneration of the adult mammalian CNS. J. Anat. 2004;204:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2004.00259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.C., Koprivica V., Kim J.A., Sivasankaran R., Guo Y., Neve R.L., He Z. Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein is a Nogo receptor ligand that inhibits neurite outgrowth. Nature. 2002a;417:941–944. doi: 10.1038/nature00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.C., Kim J.A., Sivasankaran R., Segal R., He Z. P75 interacts with the Nogo receptor as a co-receptor for Nogo, MAG and OMgp. Nature. 2002b;420:74–78. doi: 10.1038/nature01176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W.H., Liu J.Y., Qin W.J., Zhao J., Wang T., Jia L.T., Meng Y.L., Gao H., Xue C.F., Jin B.Q., et al. Targeted inhibition of HBV gene expression by single-chain antibody mediated small interfering RNA delivery. Hepatology. 2007;46:84–94. doi: 10.1002/hep.21663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler A., Wang J.T. Purification and culture of retinal ganglion cells from rodents. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013;2013:643–652. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot074906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Cui Q., Li Y., Irwin N., Fischer D., Harvey A.R., Benowitz L.I. Macrophage-derived factors stimulate optic nerve regeneration. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:2284–2293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02284.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Henzl M.T., Lorber B., Nakazawa T., Thomas T.T., Jiang F., Langer R., Benowitz L.I. Oncomodulin is a macrophage-derived signal for axon regeneration in retinal ganglion cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:843–852. doi: 10.1038/nn1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J., Kamihira M., Iijima S. Enhancement of transfection efficiency by protamine in DDAB lipid vesicle-mediated gene transfer. J. Biochem. 1999;125:1160–1167. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]