Abstract

Purpose

Racial/ethnic disparities in the incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) are well documented and many researchers have proposed that biogeographical ancestry (BGA) may play a role in these disparities. However, studies examining the role of BGA on T2DM have produced mixed results to date. Therefore, the objective of this research is to quantify the contribution of BGA to racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence controlling for the mediating influences of socioeconomic factors.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, a prospective cohort with approximately equal numbers of Black, Hispanic, and White participants. We used Ancestry Informative Markers to calculate the percentages of West African and Native American ancestry of participants. We used logistic regression with g-computation to analyze the contribution of BGA and socioeconomic factors to racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence.

Results

We found that socioeconomic factors accounted for 44.7% of the total effect of T2DM attributed to Black race and 54.9% of the effect attributed to Hispanic ethnicity. We found that BGA had almost no direct association with T2DM and was almost entirely mediated by self-identified race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors.

Conclusions

It is likely that non-genetic factors, specifically socioeconomic factors, account for much of the reported racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, biogeographic ancestry, racial/ethnic disparities, socioeconomic status, causal modeling, mediation

Disparities in type 2 diabetes (T2DM) by race/ethnicity are a pervasive public health problem in the United States and worldwide. Recent estimates from the US Centers for Disease Control report that, compared to White adults, the prevalence of diabetes is 77% higher among Black and 66% higher among Hispanic adults in the US [1]. Racial/ethnic disparities have been shown to be associated with poorer diabetes control [2], elevated rates of diabetes-related complications [3], higher rates of hospitalization [4], and greater health care costs [5]. It has been proposed in several studies that genetics, specifically, biogeographic ancestry (BGA), may explain a substantial proportion of these disparities [6].

The concepts of genetics, race, and ethnicity are often confused [7–9]. The term ‘race’ is commonly defined in terms of biological differences between groups assumed to have different biogeographical ancestries. [10]Analysis of variance of genetic variation has indicated that approximately 75% of genetic variance is found ‘within’ racial/ethnic groups, while 10% of the variance is found ‘between’ races.[10] Furthermore, the US Census categorizations (White, Black, Asian, etc.) are largely artificial constructs, as is the concept of biological race itself [9, 11]. In contrast, ethnicity is a complex multidimensional construct that reflects biological factors, geographical origins, historical influences, as well as social, cultural, economic factors [12].

A genetic basis for racial/ethnic differences in diabetes risk, the ‘thrifty gene’ hypothesis, was first proposed over 40 years ago [13]. The hypothesis has been heavily criticized from several different perspectives [7], but has nevertheless been revived in recent years as the rapid evolution of science and technologies have facilitated an expansion in genetic research. Genetic studies have established approximately 70 loci that are associated with small increases in T2DM risk [14–18]. While early studies focused primarily on people of European descent, recent studies extended this research to Black and Hispanic populations [19–21]. These studies indicate substantial overlap in the susceptibility loci across racial/ethnic groups signifying that common genetic variants contribute similarly to diabetes risk across races/ethnicities [6, 15, 21, 22] and are therefore unlikely to explain racial/ethnic differences in diabetes risk.

Since T2DM has a complex genetic etiology, it may be important to account for the substantial heterogeneity in genetic heritage that exists in admixed populations [23–26]. Individual proportions of European, African, and Native American ancestry can vary substantially among the commonly-used categories of Black [23], Hispanic [25], and White [27]. Several studies have suggested that the biologic mechanisms leading to increased T2DM risk in Black and Hispanic Americans may be related to genes associated with BGA[6, 10, 28]. However, studies examining this hypothesis by measuring Ancestry Informative Markers (AIMs), a method of estimating an individual’s genetic marker-based race/ethnicity have produced mixed results. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study found that BGA was not associated with HbA1c among African Americans and found that the contributions of demographic and metabolic factors outweighed the contributions of BGA [29]. However, an analysis of ARIC/Jackson Heart data, found that BGA was associated with T2DM among African Americans, a finding that was robust to adjustment for lifestyle and socioeconomic factors [6]. Studies among Hispanic populations have similarly produced mixed results. In a study of Columbian and Mexican participants, the association between ancestry and T2DM was attenuated, if not eliminated, when adjusting for socioeconomic factors [30]. In contrast, a study of Puerto Rican participants living in the continental US showed a negative association between African ancestry and prevalent T2DM [31]. In one of the few studies to examine the associations between ancestry and diabetes risk among African and Hispanic Americans, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) found that ancestry was significantly associated with diabetes risk, but that socioeconomic factors attenuated the effects among Hispanic but not African American women [32].

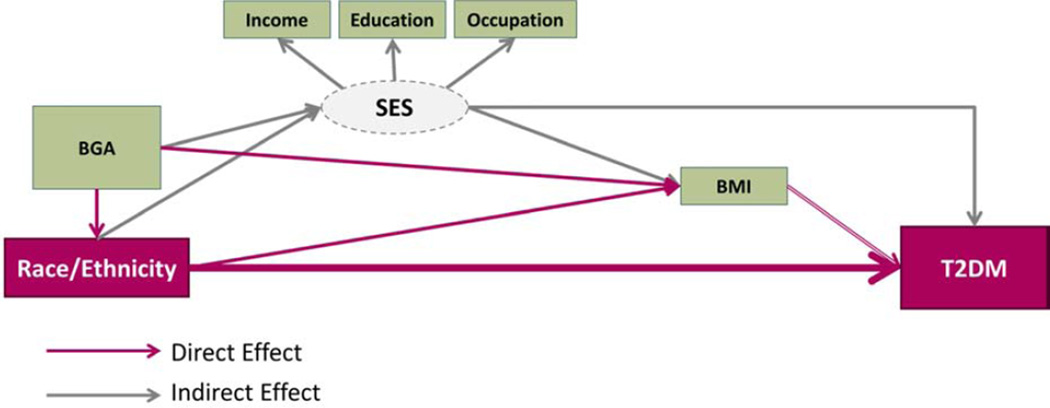

In light of these conflicting findings, further research is needed in order to validly estimate the contributions of BGA and other factors to T2DM disparities. Therefore our objectives are two-fold: 1) to quantify the contribution of African and Native American ancestry to racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence, and 2) to measure the contribution of socioeconomic status to racial/ethnic and BGA disparities in T2DM incidence (Figure 1). The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey [33] is uniquely positioned to address these research objectives given the racial/ethnic diversity of the cohort and its prospective cohort design.

Figure 1. Research Model.

- What is the contribution of BGA to racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM? (pink arrows)

- What is the indirect effect (mediation) of SES on racial/ethnic and ancestral disparities on T2DM?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey is a prospective cohort study of men and women from Boston, Massachusetts. The BACH Survey used a random stratified cluster sample design to recruit 5,502 residents (2,301 men, 3,201 women) aged 30–79 years from three racial/ethnic groups (1767 Black, 1876 Hispanic, 1859 White). Participants completed an in-person interview at baseline (2002–2005) and were contacted approximately five (BACH II: 2006–2010) and seven (BACH III: 2010–2012) years later for follow-up assessments. BACH III interviews were conducted among 3,155 (BACH III) individuals (an 81.4% conditional retention rate).

At all three time points, a home visit was conducted that included anthropometric measurements and an in-person interview, conducted in English or Spanish, to obtain information about diabetes status, comorbidities, sociodemographics, and lifestyle. AIMs were collected at BACH III only. The detailed methods have been described elsewhere [33]. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Biogeographical ancestry (BGA)

A panel of 63 uncorrelated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) were genotyped. These AIMs were selected based on their ability to estimate percent African, Native American, and European ancestry in admixed populations [25, 34]. Samples were genotyped at the Genetic Analysis Platform (GAP) at the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA) using iPLEX (Sequenom) in three batches. HapMap samples (Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry (CEU) and Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI)) were included in each batch for quality control. All Hap Map samples had 100% HapMap concordance. The average call rate for all assays was 97.4%; 1.6% of samples failed quality control with call rates <90% and two SNPs failed with call rates <90%. Ancestry proportions were estimated for individual participants using ADMIXTURE Software (version 1.12 http://www.genetics.ucla.edu/software/admixture/) using a k (the number of ancestral populations) of 3.

Race/ethnicity

Self-identified race/ethnicity was recorded using two separate survey questions as recommended by the Office of Management and Budget. The racial/ethnic categories used in this research are 1) non-Hispanic Black (Black), 2) Hispanic of any race (Hispanic), and 3) non-Hispanic White (White).

Socioeconomic status (SES)

The individual SES indicators considered were: household income, educational attainment and occupation, measured at baseline. Household income, originally grouped into 12 ordinal categories, was collapsed into the following three categories of US dollars: <20,000, 20–49,999, and ≥50,000. These categories were specified a priori based on literature review. However, other parameterizations were considered to ensure adequate control of confounding. Educational attainment was categorized as: 1) less than high school; 2) high school graduate or equivalent; 3) some college; and 4) college or advanced degree. Current or former occupation was categorized as follows: 1) management, professional, sales and office occupations; 2) service occupations; 3) manual labor; and 4) never worked. We use the broader term ‘SES’ when referring to these three distinct socioeconomic factors in the aggregate, all of which are strongly related to overall health.

Type 2 diabetes

Participants were asked at baseline (BACH I) and follow-up (BACH II and III) whether a doctor or health care professional had ever told them that they have diabetes. Individuals diagnosed with diabetes at baseline were excluded from these analyses (n=432). Incident cases of T2DM were defined as new diagnoses of T2DM at BACH II or BACH III (n=260, 6.4%). The use of insulin or oral medications for diabetes was collected by medication inventory at all three time-points and sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the potential for self-report bias. We also conducted confirmatory cross-sectional analyses using BACH III data. At BACH III prevalent diabetes cases were defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or self-report of a diabetes diagnosis confirmed by medication inventory (Appendix A).

Statistical methods

In order to reduce the potential for bias due to missing data and to minimize reductions in precision,[35, 36] multiple imputation was implemented for item non-response using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) [37] in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna Austria). 822 participants (26%) were missing data on BGA (i.e. % West African, Native American, and European ancestry), 248 (8%) education, 184 (6%) household income, <1% occupation, and <1% BMI. Fifteen multiple imputation datasets were created for each racial/ethnic by gender combination. Analyses were replicated on the complete data and the results were essentially the same as those obtained from the multiple imputation. In this paper, we therefore present results from the multiple imputation models because the precision of the estimates is improved by the increased sample size, and the full data set is less likely to be subject to bias.[38, 39]

Statistical analyses were performed using SUDAAN 11 (Research Triangle Park, North Carolina), Stata/SE Version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas), and Mplus Version 7 (Muthen and Muthen, Los Angeles, CA). To account for the BACH survey design (a stratified, two-staged cluster sample including oversampling of black and Hispanic participants),[33, 40] data observations were weighted inversely to their probability of selection at baseline to produce unbiased estimates of the Boston population. Survey weights were adjusted for non-response bias at follow-up using the propensity cell adjustment approach,[41] and post-stratified to the Boston census population in 2010.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on the predicted marginal risk in SUDAAN. All p-values are two-sided. BMI and other relevant lifestyle/behavioral mediators were considered including physical activity, dietary patterns, alcohol consumption, high blood pressure and high cholesterol. BGA was modeled as the proportion of West African (ranging from 0 to 1) and Native American ancestry (also ranging from 0 to 1). The RRs for 100% West African and 100% Native American ancestry versus 100% European ancestry are reported for ease of interpretation.

We performed mediation analysis to assess what degree of the racial/ethnic (or ancestry) effect is explained by socioeconomic status (the mediating influence). The excess relative risk (ERR) was calculated to quantify the risk attributable to a given exposure (i.e. Black race or Hispanic ethnicity). The unadjusted ERR is one method to estimate the “total effect” of race/ethnicity. The “indirect effect” or “mediated effect” due to SES was estimated using the SES-adjusted ERR. An estimate of the percent of the total effect that is mediated by SES was calculated as: (unadjusted ERR - adjusted ERR)/unadjusted ERR. Since BMI is likely influenced by SES (Figure 1), BMI was introduced only in the SES-adjusted models and is not included in the calculation of mediation effects.

There are limitations to using standard regression techniques to estimate mediation[42] and under some circumstances, these techniques may fail to produce valid estimates. For example, traditional regression techniques may not adequately control for confounding between the mediator and the outcome[43]. Therefore, we also used g-computation[44] to supplement the traditional regression techniques. The g-computation procedure estimates the total causal effects as well as natural direct and indirect effects[43, 44]. Since the g-computation procedure in Stata (gformula) has only been developed on an additive (risk difference) scale and does not currently support survey sample weights, we conducted an unweighted analysis with three estimates: 1) excess relative risk estimates using unweighted data (for comparison to the weighted estimates), 2) risk differences estimates from traditional regression techniques, and 3) risk differences obtained from g-computation. All models were age and gender adjusted. We included BMI in the g-computation estimate as an exposure dependent confounder of the mediator outcome association.

RESULTS

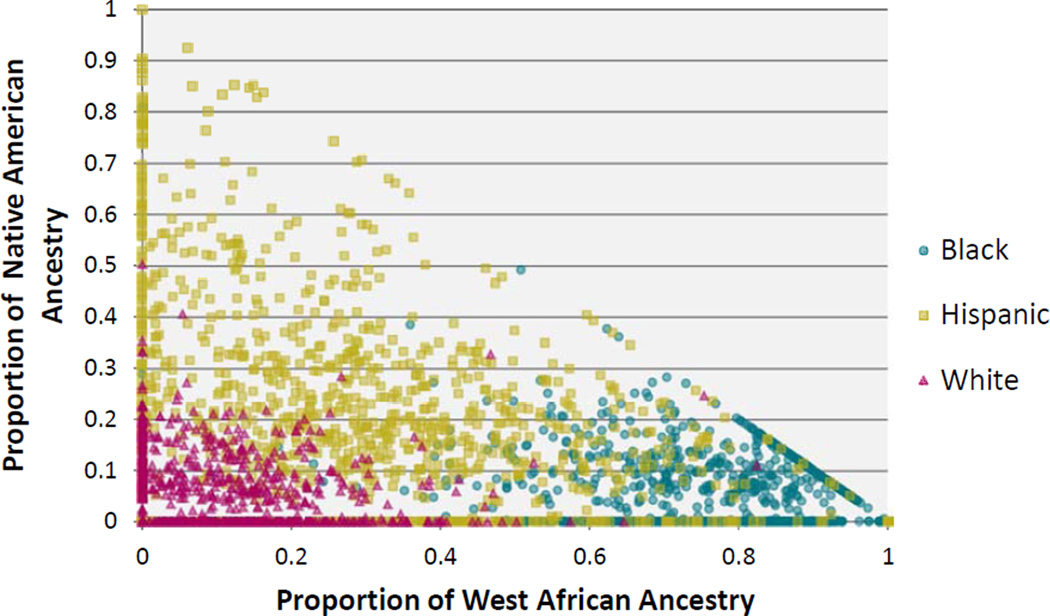

The demographic characteristics of the 2,723 men and women in the analytic sample are presented in Table 1. The mean and standard error (SE) time between the baseline (BACH I) and follow-up (BACH III) assessments was 7.2 (0.3) years. Over 25% of the sample had a household income < $25,000, over one-third had a high school education or less, and over two-thirds were overweight or obese. We estimated individual ancestry with respect to three ancestral populations: West African, Native American, and European (Figure 2). For Black participants, the ancestral composition is on average 78% West African (95% CI: 75–80%), 5% Native American (4–6%), and 17% European (15–20%). Hispanic participants were on average 29% West African (26–33%), 22.4% Native American (19–26%), and 48% European (45–52%) and had the greatest degree of variability around these measures due to the high degree of admixture. White participants were on average 9% West African (8–9%), 5% Native American (4–6%), and 87% European (86–88%). Figure 2 demonstrates that while BGA (represented as % Native American and % African ancestry) was highly correlated with self-identified race/ethnicity, there was substantial variability in the individual proportions, particularly among Blacks and admixed Hispanics. For example, among self-identified Black participants, the minimum percentage of West African ancestry was 0.001% and the maximum was 99.99% (not imputed). Similarly wide ranges were seen for Native American ancestry (min: 0.001%, max: 80.9%) among Black participants; for African (min: 0.001%, max: 99.99%) and Native American (min: 0.001%, max: 99.99%) ancestry among Hispanic participants; and even African (min: 0.001%, max: 82.4%) and Native American (min: 0.001, max: 50.3%) ancestry among White participants (Figure 2). The overall cumulative incidence of T2DM over the follow-up period was 6%, with a cumulative incidence of 10% among Black, 6% among Hispanic, and 5% among White participants.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Self Reported Race/Ethnicity at Baseline

| Race/ethnicity Number (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black N=863 |

Hispanic N=870 |

White N=990 |

Total N=2723 |

|

| Age | ||||

| 30–39 | 225 (50.38) | 278 (63.72) | 199 (39.11) | 702 (45.10) |

| 40–59 | 281 (23.27) | 267 (21.34) | 247 (24.34) | 795 (23.69) |

| 60–69 | 210 (14.56) | 198 (8.62) | 260 (14.41) | 668 (13.74) |

| 70–79 | 108 (7.75) | 96 (4.49) | 194 (13.09) | 398 (10.62) |

| 80+ | 39 (4.04) | 31 (1.84) | 90 (9.05) | 160 (6.84) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 312 (42.57) | 292 (45.77) | 420 (48.33) | 1024 (46.49) |

| Female | 551 (57.43) | 578 (54.23) | 570 (51.67) | 1699 (53.51) |

| Biogeographical Ancestry (mean %, SE) | ||||

| African | 77.72 (1.25) | 29.24 (1.70) | 8.52 (0.46) | 29.41 (1.33) |

| Native American | 5.01 (0.41) | 22.35 (1.62) | 4.93 (0.30) | 7.08 (0.32) |

| European | 17.27 (1.19) | 48.41 (1.95) | 86.55 (0.54) | 63.51 (1.35) |

| Income | ||||

| <$20,000 | 372 (38.16) | 552 (51.34) | 237 (17.82) | 1161 (27.31) |

| $20,000 –$49,999 | 322 (38.62) | 252 (35.53) | 281 (26.70) | 855 (30.94) |

| ≥ $50,000 | 169 (23.22) | 66 (13.13) | 472 (55.48) | 707 (41.75) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than High School | 137 (11.26) | 367 (36.58) | 74 (4.04) | 578 (9.93) |

| High school or equivalent | 375 (45.47) | 293 (35.53) | 235 (19.13) | 903 (28.12) |

| Some college | 181 (22.60) | 109 (12.29) | 131 (11.02) | 422 (14.25) |

| College or advanced degree | 170 (20.67) | 101 (15.60) | 550 (65.81) | 821 (47.70) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Professional, Managerial, Sales, and Office | 449 (58.55) | 270 (37.72) | 735 (80.03) | 1454 (69.17) |

| Service | 223 (21.10) | 341 (36.81) | 121 (8.17) | 685 (15.09) |

| Manual labor | 180 (19.52) | 209 (20.74) | 118 (9.42) | 507 (13.48) |

| Never worked | 11 (0.83) | 50 (4.73) | 16 (2.39) | 77 (2.26) |

| Neighborhood SES | ||||

| Low | 581 (66.24) | 482 (51.00) | 255 (18.24) | 1318 (34.97) |

| Middle | 143 (16.42) | 192 (24.16) | 372 (39.55) | 707 (31.54) |

| High | 138 (17.34) | 196 (24.84) | 363 (42.21) | 697 (33.49) |

| BMI | ||||

| Normal (<25) | 177 (21.48) | 175 (28.01) | 314 (34.39) | 666 (30.18) |

| Overweight (25–30) | 269 (29.33) | 359 (38.69) | 351 (39.53) | 978 (36.72) |

| Obese (≥30) | 417 (49.19) | 336 (33.30) | 325 (26.08) | 1078 (33.10) |

Figure 2. Biogeographical Ancestry by Self-Identified Race/Ethnicity.

What is the contribution of African and Native American ancestry to racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence?

In age and gender adjusted models, Black participants were 2.3 times as likely to report having developed diabetes (RR=2.3; 95% CI: 1.4–3.7) and Hispanics were 1.7 times as likely to report new diabetes (RR=1.7; 1.0–2.8) than White participants (Table 2). The excess relative risk (ERR) indicates that Black participants are 128% more likely, and Hispanic participants 67% more likely, to develop T2DM over the study period compared to White participants. Adjustment for BGA increased these estimates slightly and widened the confidence intervals (Black vs. White: RR=2.6; 0.9–7.2; Hispanic vs. White: RR=2.0; 1.1–3.8).

Table 2.

Risk Ratios for Diabetes Incidence by Self-Identified Race/Ethnicity (Longitudinal)1

| Black vs. White | Hispanic vs. White | Adjusted for | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | CI | ERR | RR | CI | ERR | ||

| Base model | 2.28 | 1.40–3.71 | 1.28 | 1.67 | 1.00–2.80 | 0.67 | Gender and age |

| Ancestry adjusted | 2.57 | 0.92–7.19 | 1.57 | 2.02 | 1.07–3.80 | 1.02 | Gender, age, African, and Native American ancestry |

| SES adjusted | 1.46 | 0.88–2.44 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.47–1.51 | −0.16 | Gender, age, income, education, and occupation |

| Ancestry and SES adjusted | 1.71 | 0.58–5.07 | 0.71 | 1.02 | 0.50–2.09 | 0.02 | Gender, age, African, and Native American ancestry, income, education, and occupation |

| Ancestry, SES, and BMI adjusted | 1.55 | 0.52–4.61 | 0.55 | 1.11 | 0.55–2.21 | 0.11 | Gender, age, African, and Native American ancestry, income, education, occupation, and BMI |

| % mediated by SES2 | 64% | 100% | Indirect effect through SES/Total effect of race/ethnicity * 100 | ||||

Corresponds to the black arrows in Figure 1

% mediated (indirect effect over the total effect) is calculated as: ((ERRBase model) – (ERRSES adjusted model)) / (ERRBase model)

RR=Relative Risk

ERR=Excess Relative Risk (RR-1)

We examined the relationship between 1 unit increments of African and Native American ancestry on incident T2DM (Table 3). In age- and gender-adjusted models, the risk of developing T2DM were on average 1.6 times higher (RR= 2.6; 1.3–5.0) for an individual with 100% African ancestry versus an individual with 100% European ancestry. There was no relationship between Native American ancestry and developing T2DM (RR=1.0; 0.2–4.9).

Table 3.

Risk Ratios for Diabetes Incidence by Biogeographical Ancestry (Longitudinal)1

| 100% West African vs. 100% European |

100% Native American vs. 100% European |

Adjusted for | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | CI | ERR | RR | CI | ERR | ||

| Base model | 2.56 | 1.33–4.95 | 1.56 | 1.01 | 0.21–4.90 | 0.01 | Gender and age |

| Race/ethnicity adjusted | 0.86 | 0.19–3.94 | −0.14 | 0.42 | 0.07–2.66 | −0.58 | Gender, age, and self-identified race/ethnicity |

| SES adjusted | 1.52 | 0.77–3.01 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.08–2.31 | −0.57 | Gender, age, income, education, and occupation |

| Race/ethnicity and SES adjusted | 0.82 | 0.18–3.76 | −0.18 | 0.46 | 0.07–2.96 | −0.54 | Gender, age, self-identified race/ethnicity, income, education, and occupation |

| Race/ethnicity, SES, and BMI adjusted | 0.83 | 0.18–3.90 | −0.17 | 0.40 | 0.06–2.59 | −0.60 | Gender, age, self-identified race/ethnicity, income, education, occupation, and BMI |

| % mediated by SES2 | 67% | N/A4 | Indirect effect through SES/Total effect of race/ethnicity * 100 | ||||

| % mediated by Race/ethnicity and SES3 | 100% | N/A4 | Indirect effect through Race/ethnicity and SES/Total effect of race/ethnicity * 100 | ||||

Corresponds to the gray arrows in Figure 1

% mediated (indirect effect over the total effect) is calculated as: ((ERRBase model ) – (ERRSES adjusted model )) / (ERRBase model )

% mediated (indirect effect over the total effect) is calculated as: ((ERRBase model ) – (ERRRace/ethnicity and SES adjusted model )) / (ERRBase model )

The base model indicated no total effect, % mediated was not calculated

RR=Relative Risk

ERR=Excess Relative Risk (RR-1)

What is the contribution of socioeconomic status to racial/ethnic and ancestral disparities in T2DM?

Adjusting for SES (income, occupation, and education) attenuated the racial/ethnic disparities (Black vs. White: RR=1.7; 0.6–5.1; Hispanic vs. White: RR=1.1; 0.6–2.2, Table 2). The traditional mediation analyses indicated that SES accounted for 64% of the total effect attributed to Black race and 100% of the total effect attributed to Hispanic ethnicity. Further adjustment for BMI only changed the risk ratios slightly. Estimates adjusting for other lifestyle/behavioral factors are not reported since their effects were negligible (< 3%). Consistent with previous studies and with the results by self-report race/ethnicity, the effects of BGA were attenuated with adjustment for socioeconomic factors (African ancestry: RR=1.5; 0.8–3.0; Native American ancestry: RR=0.4; 0.1–2.3, Table 3). The mediation analyses indicated that SES accounted for 67% of the total effect attributed to West African ancestry. We tested for statistical interaction between ancestry and socioeconomic factors and found no statistically significant interactions.

The findings from the G-computation (Table 4, unweighted data) largely agree with the findings from the standard regression techniques. The g-computation estimated the proportion mediated by SES to be lower, indicating that 45% of the Black vs. White effect, and 55% of the Hispanic vs. White effect was mediated by SES. Both the traditional regression techniques and the g-computation indicated that African ancestry was 82% mediated by race/ethnicity and SES and that there was no direct effect of Native American Ancestry on T2DM.

Table 4.

The Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of Race/Ethnicity and Biogeographical Ancestry on T2DM, Estimated Using Standard Regression Models and G-computation Using Unweighted Data

| Excess Relative Risk Method1 | Risk difference Method1 | G-computation1,2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Hispanic | Black | Hispanic | Black | Hispanic | |||||||

| CI |

CI |

CI |

CI |

CI |

CI |

|||||||

| Total effect | 0.90 | 0.39, 1.59 | 1.19 | 0.61, 1.98 | 0.05 | 0.03, 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05, 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.002, 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01, 0.04 |

| Direct effect | 0.42 | 0.01, 1.00 | 0.40 | −0.02, 1.01 | 0.03 | −0.009, 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.009, 0.07 | 0.008 | −0.008, 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.005, 0.03 |

| Indirect/Total effect3 | 53.3% | 66.4% | 60.0% | 42.9% | 44.7% | 54.9% | ||||||

| African Ancestry |

Native American Ancestry |

African Ancestry |

Native American Ancestry |

African Ancestry |

Native American Ancestry |

|||||||

| CI |

CI |

CI |

CI |

CI |

CI |

|||||||

| Total effect | 0.84 | 0.29, 1.64 | 1.12 | 0.04–3.32 | 0.06 | 0.02, 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.02, 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.02, 0.07 | 0.008 | −0.01,0.03 |

| Direct effect | 0.15 | −0.49, 1.60 | −0.28 | −0.75, 1.09 | 0.01 | −0.07, 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.11, 0.05 | 0.009 | −0.02, 0.04 | −0.0006 | −0.02, 0.02 |

| Indirect/Total effect4 | 82.1% | 100.0% | 83.3% | 100.0% | 82.1% | 100.0% | ||||||

All estimates are adjusted for age and gender

BMI is allowed to be an intermediate confounder in the mediator – outcome relationship

The indirect/total effect is the % of the racial/ethnic effect on T2DM that is mediated by SES

The indirect/total effect is the % of the BGA effect on T2DM that is mediated by race/ethnicity and/or SES

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study, we report on two key findings. First, we found that racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM were potentially mediated by SES, whereas BGA had no effect on this relationship. Second, we found that while African ancestry is significantly associated with T2DM incidence, a large proportion of this association was mediated by self-identified race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors. These findings were consistent with the results from g-computation, which indicated that SES accounted for approximately half of the racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence and nearly all of the BGA differences.

Our estimates of the magnitude of racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM risk are in line with national trends [1]. In the BACH sample, the approximate 7-year incidence of T2DM was twice as high among Black versus White participants, and 60% higher among Hispanic versus White participants. In our unadjusted estimates of the effect of BGA we found that having 100% African ancestry versus 100% European ancestry conferred a 1.5 fold risk of T2DM. Due to the conflicting findings regarding BGA to date, the finding that socioeconomic status explains a large proportion of this association agrees with some studies [29, 30, 32] but is in contrast with others [6, 31, 32].

Race/ethnicity is a complex multidimensional construct reflecting biological factors, geographical origins, as well as social, cultural, and economic factors [12]. These analyses indicate that while genetic factors, including bio-geographic ancestry, may play a role in T2DM, it is likely that the social, cultural, and economic facets of race/ethnicity better explain T2DM disparities in the US. Specifically, the lower average SES of Blacks and Hispanics in the US, compared with that of Whites, provides a plausible explanation for a large proportion of the excess risk of T2DM.

Strengths and limitations

A potential limitation of this study is the reliance on self-report for incident diabetes outcomes. However, our sensitivity analyses (available as an Appendix), which use objective measures of diabetes status, largely agree with the data presented here. In addition, research has shown that self-report of major medical conditions correlate well with medical record review [45] and over 80% of self-report incident cases were confirmed by medication inventory. Another limitation to this analysis is the lack of detailed information on changes in risk factors over time. While BGA and race/ethnicity are constant, the effects of socioeconomic and lifestyle/behavioral factors may be fine-tuned in a proportional hazards regression model. However, our study does provide evidence for a temporal effect between SES and diabetes incidence whereas many studies of BGA have been limited to cross-sectional [6, 30, 31] or limited measures of SES [30–32]. Finally, although the sample is geographically limited to Boston, Massachusetts, the BACH Survey sample has been compared to other large regional (Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) and national (the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) on a number of socio-demographic and health-related variables.[40] The results suggest that the BACH Survey estimates of key health conditions are comparable with national trends.

The key strengths of this study stem from the community-based random sample design of the BACH Survey. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the effects of BGA in a large cohort of Black, Hispanic, and White men and women. Most of the literature on the effects of BGA on T2DM have been restricted to one racial or ethnic group, such as African Americans [6] or Hispanics [30, 31] with the exception of the WHI [32]. Limiting the sample to one racial/ethnic group may restrict on the cultural, social, and economic factors that most directly appear to influence T2DM.

Another key strength of this study is the analytic strategy which was grounded in a causal modeling framework. The sensitivity analyses using the G-computation formula allow us to estimate the total causal effect as well as natural direct/indirect effects and allowed flexibility to the modeling assumptions [43].

Conclusions

Racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM are well documented. However, it is likely that a proportion of the excess risk in T2DM attributed to race/ethnicity is explained by differences in social and economic circumstances. These results have profound implications for informing appropriate prevention strategies. It is likely that non-genetic factors, namely socioeconomic factors, lead to the observed racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM incidence, and the continued focus on genetic causes of disparities in T2DM is likely misplaced. Appropriate prevention strategies need to address the root causes for these disparities, which appear to be largely socioeconomic in nature.

Acknowledgements

Source of Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (DK080786, PI: John B. McKinlay and DK080140, PI: James Meigs).

We thank Dr. James Meigs of Massachusetts General Hospital and Dr. Richard Grant of Kaiser Permanente for their assistance in parameterizing the Ancestry Informative Markers (AIMs); Dr. Jay Kaufman of McGill University for his valuable input to earlier versions of this paper; Dr. Jonathan Bartlett and Dr. Chris Frost both of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for their valuable input regarding the statistical analyses.

Abbreviations

- AIMS

Ancestry Informative Markers

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- BACH

Boston Area Community Health

- BGA

Biogeographic ancestry

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- MICE

Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations

- RMSEA

Root mean square error of approximation

- RR

Risk ratio

- SE

Standard error

- SES

Socioeconomic status

- T2DM

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- WHI

Women’s Health Initiative

Appendix A: Supplementary Cross-Sectional Analysis

Notes: For the confirmatory cross-sectional analyses, the prevalence of diabetes was 21.8% (980 prevalent cases).

Table A1.

Risk Ratios for Diabetes Prevalence1 by Self-Identified Race/Ethnicity (BACH III Confirmatory Cross-Sectional Analysis)2

| Black vs. White | Hispanic vs. White |

Adjusted for | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | CI | RR | CI | ||

| Base model | 2.05 | 1.59–2.63 | 1.57 | 1.18–2.11 | Gender and age |

| Ancestry adjusted | 1.91 | 1.18–3.09 | 1.60 | 1.09–2.36 | Gender, age, African, and Native American ancestry |

| SES adjusted | 1.57 | 1.22–2.02 | 0.98 | 0.72–1.34 | Gender, age, income, education, and occupation |

| Ancestry and SES adjusted | 1.49 | 0.89–2.50 | 1.02 | 0.67–1.56 | Gender, age, African, and Native American ancestry, income, education, and occupation |

| Ancestry, SES, and BMI adjusted | 1.43 | 0.85–2.38 | 1.02 | 0.67–1.54 | Gender, age, African, and Native American ancestry, income, education, occupation, and BMI |

| % mediated by SES3 | 45.7% | 100% | Indirect effect/Total effect | ||

Diabetes prevalence defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or self-report of a diabetes diagnosis

Corresponds to the black arrows in Figure 1

% mediated(indirect effect over the total effect) is calculated as: ((RRBase model -1) – (RRSES adjusted model - 1)) / (RRBase model - 1)

RR=Relative Risk

Table A2.

Risk Ratios for Diabetes Prevalence1 by Biogeographical Ancestry (BACH III Confirmatory Cross-Sectional Analysis)2

| West African | Native American | Adjusted for | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | CI | RR | CI | ||

| Base model | 2.35 | 1.72–3.21 | 1.41 | 0.65–3.05 | Gender and age |

| Race/ethnicity adjusted | 1.13 | 0.58–2.21 | 0.80 | 0.27–2.36 | Gender, age, and self-identified race/ethnicity |

| SES adjusted | 1.74 | 1.26–2.39 | 0.73 | 0.29–1.85 | Gender, age, income, education, and occupation |

| Race/ethnicity and SES adjusted | 1.10 | 0.55–2.20 | 0.76 | 0.26–2.24 | Gender, age, self-identified race/ethnicity, income, education, and occupation |

| Race/ethnicity, SES, and BMI adjusted | 1.11 | 0.56–2.21 | 0.79 | 0.28–2.22 | Gender, age, self-identified race/ethnicity, income, education, occupation, and BMI |

| % mediated by race/ethnicity and SES3 | 92.5% | 100% | Indirect effect/Total effect | ||

Diabetes prevalence defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or self-report of a diabetes diagnosis

Corresponds to the gray arrows in Figure 1

% mediated (indirect effect over the total effect) is calculated as: ((RRBase model-1 ) – (RRRace/ethnicity and SES adjusted model -1)) / (RRBase model -1)

RR=Relative Risk

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.C.f.D.C.a.P. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirk JK, et al. Disparities in HbA1c levels between African-American and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2130–2136. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanting LC, et al. Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients: a review. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2280–2288. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. [cited 2012 August 4];Diabetes and African Americans. Available from: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=51&ID=3017.

- 5.Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):596–615. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng CY, et al. African ancestry and its correlation to type 2 diabetes in African Americans: a genetic admixture analysis in three U.S. population cohorts. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearce N, et al. Genetics, race, ethnicity, and health. BMJ. 2004;328(7447):1070–1072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7447.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger N, et al. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):312–323. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.032482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper RS, Kaufman JS, Ward R. Race and genomics. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1166–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb022863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Risch N, et al. Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease. Genome Biol. 2002;3(7) doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-comment2007. p. comment2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krieger N. Stormy weather: race, gene expression, and the science of health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2155–2160. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR. Race and health: basic questions, emerging directions. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(5):322–333. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neel JV. Diabetes mellitus: a "thrifty" genotype rendered detrimental by "progress"? Am J Hum Genet. 1962;14:353–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy MI. Genomics, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2339–2350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0906948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxena R, et al. Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 39 studies identifies type 2 diabetes loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(3):410–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupuis J, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42(2):105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris AP, et al. Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):981–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voight BF, et al. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet. 2010;42(7):579–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gamboa-Melendez MA, et al. Contribution of common genetic variation to the risk of type 2 diabetes in the mexican mestizo population. Diabetes. 2012;61(12):3314–3321. doi: 10.2337/db11-0550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos E, et al. Replication of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) loci for fasting plasma glucose in African-Americans. Diabetologia. 2011;54(4):783–788. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-2002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waters KM, et al. Consistent association of type 2 diabetes risk variants found in europeans in diverse racial and ethnic groups. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Q, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in association of fasting glucose-associated genomic loci with fasting glucose, HOMA-B, and impaired fasting glucose in the U.S. adult population. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2370–2377. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parra EJ, et al. Estimating African American admixture proportions by use of population-specific alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(6):1839–1851. doi: 10.1086/302148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halder I, et al. A panel of ancestry informative markers for estimating individual biogeographical ancestry and admixture from four continents: utility and applications. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(5):648–658. doi: 10.1002/humu.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price AL, et al. A genomewide admixture map for Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(6):1024–1036. doi: 10.1086/518313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabriel SB, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296(5576):2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halder I, et al. Measurement of admixture proportions and description of admixture structure in different U.S. populations. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(9):1299–1309. doi: 10.1002/humu.21045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Risch N. Dissecting racial and ethnic differences. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):408–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maruthur NM, et al. Does genetic ancestry explain higher values of glycated hemoglobin in African Americans? Diabetes. 2011;60(9):2434–2438. doi: 10.2337/db11-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Florez JC, et al. Strong association of socioeconomic status with genetic ancestry in Latinos: implications for admixture studies of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52(8):1528–1536. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1412-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai CQ, et al. Population admixture associated with disease prevalence in the Boston Puerto Rican health study. Hum Genet. 2009;125(2):199–209. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi L, et al. Relationship between diabetes risk and admixture in postmenopausal African-American and Hispanic-American women. Diabetologia. 2012;55(5):1329–1337. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piccolo RS, et al. Cohort Profile: The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ije/dys198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith MW, et al. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in african americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(5):1001–1013. doi: 10.1086/420856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterne JA, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Little R, DB R. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Mutlivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(3):1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(12):1255–1264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Heijden GJ, et al. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(10):1102–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52(2):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heeringa S, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press; 2010. pp. xix–467. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hafeman DM. "Proportion explained": a causal interpretation for standard measures of indirect effect? Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1443–1448. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daniel RM, De Stavola BL, Cousens SN. gformula: Estimating causal effects in the presence of time-varying confounding or mediation using the g-computation formula. Stata Journal. 2010;11(4):479–517. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robins JM, Greenland S. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 1992;3(2):143–155. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okura Y, et al. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]