Abstract

Background:

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing globally. Studies on this subject, especially in the older age groups are difficult to come by in developing countries like Nigeria.

Aim:

The aim of this study, therefore, is to estimate the prevalence of CKD in retired and elderly Nigerian subjects.

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 170 retired subjects were recruited for the study. Anthropometric measurements were carried out and blood samples taken for serum urea and creatinine estimation. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was determined using software by Kidney Health Australia. The figures obtained thereafter were multiplied by 1.21 to accommodate for the black race. Differences between subjects were tested, using Chi-squared test for categorical data, while two tailed unpaired t-test was used for comparison of means. A significant difference was defined as (P < 0.05)

Results:

A total of 170 subjects with age ranged between 50 and 86 years, with a mean age of 68.1 (7.7) years (95% confidence interval [CI = 66.9-69.3]) completed this study. Male: Female ratio was 2:1 and 66.5% (113/170) of subjects were elderly (above 65 years). eGFR of subjects ranged from 31 to 114 ml/min/1.73 m2, with a mean of 64.5 (16.5) ml/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI = 62.0-67.0). The prevalence of CKD in the general population studied was 43.5% (74/170), whereas that in the elderly sub-population was 40.7% (46/113). In the non-elderly subjects, CKD was observed in 49.1% (28/57) of subjects. There was no statistically significant difference between the prevalence of CKD in both groups (P = 0.53). The prevalence of CKD was significantly higher in the female subjects than their male counterparts. Subjects with CKD had 33.33% (38/74) males and 64.3% (36/74) females.

Conclusion:

Prevalence of CKD in this studied population is quite high. More aggressive public health measures are required to stem the tide.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Estimated glomerular filtration rate, Retired subjects

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is rising globally and causing enormous socio-economic burdens for societies and the health care systems across the globe. Data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2004) suggest that about 1 out of 8 adult Americans exhibit evidence of CKD.[1] Comparable estimates have been reported in Asia,[2] Australia,[3] and across Europe.[4,5,6] It is more difficult to get accurate estimates in the developing countries like Nigeria, due to lack of national registries of CKD and limited surveys. However, the risk factors for CKD are known to be just as prevalent in many developing countries as in the developed countries. Therefore, the burden of CKD in those developing countries may be comparable to those of the developed countries. In addition, developing countries exhibit a disproportionate burden of infectious and environmental factors that broaden the spectrum of CKD risk factors and are apt to increase CKD burden.

In both Canada[7] and the United States[8] subjects aged 65 and older are the most rapidly growing segment of the population starting dialysis.

Underlying these numbers in the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) population is a high prevalence of Stages 3 and 4 CKD in the elderly, with rates of 25%[9] to 55% respectively.[3] Because CKD in this age group and others is a marker of poor outcome, including cardiovascular disease and decreased survival,[10] emphasis has been placed on early detection and implementation of strategies to slow the progression of CKD.[11]

In the United States, approximately one in three adults aged 65 years and older has CKD defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min/1.73 m2.[12] The majority of patients with CKD do not progress to advanced stages of CKD because death precedes the progression to ESRD, even among patients with Stage 4 CKD.[13] The risk of death when compared to the risk of progression to ESRD may be even higher in older patients with established CKD.

Although many CKD risk factors can be managed and modified to optimize clinical outcomes, the prevailing socioeconomic and cultural factors in disadvantaged populations, more often than not, militate against optimum clinical outcomes. In addition, disadvantaged populations exhibit a broader spectrum of CKD risk factors and may be genetically predisposed to an earlier onset and a more rapid progression of CKD.

The incidence of CKD in Nigerian adults has been shown in various studies to range between 1.6% and 12.4% respectively.[14,15,16,17,18]

Our hypothesis is that a high burden of CKD is likely in elderly Nigerian subjects, because of the extra burden of ignorance and infectious diseases. After a detailed search for studies on the prevalence of CKD on retired or elderly Nigerians, there were no data found.

The aim of this study, therefore, is to estimate the prevalence of CKD in retired and elderly Nigerian subjects.

Subjects and Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive study on the prevalence of CKD, using eGFR measurement in a retired Nigerian population.

A total of 220 attendees to the quarterly medical lectures of the Ebreime Foundation for the elderly, were screened at, the medical clinics of the Federal Medical Center, Asaba between August and September 2011.

The Ebreime Foundation for the elderly and physically challenged is a non-profit, non-governmental organization, which among other activities, holds quarterly medical lectures for elderly subject in a town hall meeting format. Invitation to meetings was advertised on radio and television and by telephone text messages to regular attendees. Attendance is voluntary and subjects are expected to transport themselves to the advertised venue.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethics committee of Federal Medical Center, Asaba.

Study population

All attendees underwent a detailed history and physical examination, with emphasis on recent ingestion of nephrotoxic agents (drugs and dyes), recent history of significant trauma or fluid loss and recent history of febrile illness. Those who had experienced any of these conditions in the preceding 1 month were excluded. Those with incomplete data and those who denied consent, were also excluded. At the end of the screening, 50 attendees were considered ineligible for the study. The remaining 170 subjects were grouped in batches and screened over 4 weeks. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. A data proforma was used to record biodata, medical history, and regular medications, among other parameters. Anthropometrics measurements were obtained, using standard hospital equipment.

Biochemical analysis

From each participant, 5 cc of blood was collected from a suitable vein after an overnight fast, into plain blood containers and sent to the laboratory. Serum of subjects was analyzed by colorimetry at the chemical pathology laboratory of Federal Medical Center, Asaba for creatinine, the Rehbery-Folin method of Jaffe's reaction, using the Olympus AU600 auto analyzer and the coefficient of variation was <1.9%. This method is traceable by isotope dilution-mass spectrometry. EGFR was calculated by the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation (MDRD eGFR [ml/min/1.73 m2]) =175 × ([serum creatinine [μmol/L]/88.4]−1.154) × (age in years)−0.203 × (0.742 if female) × (1.210 if African-American) (which has been validated in Nigerian adults),[19,20] using software by Kidney Health Australia, which utilizes an abbreviated, four variable MDRD equation. Each subject's age, sex, weight and serum creatinine were fed into the provided spaces and the eGFR was generated by the computer. Results were multiplied by 1.21 to accommodate for race (black race).

Statistical analysis

Data was stored in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 17.0 (Chicago II, USA) for statistical analysis. Differences between subjects were tested, using Chi-squared test for categorical data, while two tailed unpaired t-test was used for comparison of means. A significant difference was defined as (P < 0.05).

Results

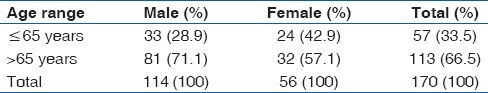

A total of 170 subjects were recruited for this study [Table 1]. The ages of the subjects ranged between 50 and 86 years, with a mean age of 68.1 (7.7) years (95% confidence interval [CI = 66.9-69.3]). Subjects comprised of 67.1% (114/170) males and 32.9% (56/170) females, giving a male: Female ratio of 2:1. 66.5% (113/170) of the studied population were elderly (above 65 years), while 33.5% (57/170) were below 65 years Among the elderly sub group, 71.7% (81/113) and 28.3% (32/113) were male and female respectively, while in the non-elderly population only 57.9% (33/57) were male and 42.1% (24/57) female.

Table 1.

Sex and age distribution of the subjects

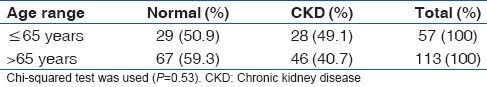

Table 2 shows the eGFR of subjects. Their eGFR ranged between 31 and 114 ml/min/1.73 m2, with a mean of 64.5 (16.5) ml/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI = 62.0-67.0). EGFR was used to classify subjects into normal (above 60 ml/min) and CKD (below 60 ml/min). Of the 170 subjects studied, 96 had normal GFR, while 74 had CKD, giving a CKD prevalence rate of 43.5% (74/170) in the general population studied. Of the 113 elderly subjects, 59.3% (67/113) had normal GFR, while 40.7% (46/113) had CKD. While in the non-elderly population, 50.9% (29/57) had normal GFR, while 49.1% (28/57) had CKD. All the subjects with CKD belonged to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Stage 3, with the lowest eGFR recorded among the subjects being 31 ml/min/1.73 m2

Table 2.

Prevalence of CKD according to age groups of subjects

There was no significant statistical difference in the prevalence of CKD between the elderly and non-elderly groups (P = 0.53).

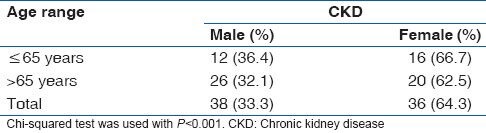

The prevalence of CKD according to gender is presented in Table 3. Among a total of 114 male subjects, 33.33% (38/114) had CKD. The elderly sub population of male subjects had 32.1% (26/81) CKD, whereas the non-elderly male subjects had 36.4% (12/33) CKD.

Table 3.

Prevalence of CKD according to gender

Prevalence of CKD observed among female subjects was 64.3% (36/56). The elderly sub-population of females showed 62.5% (20/32) CKD while 66.7% (16/24) was found among the non-elderly females subjects.

The prevalence of CKD among the female group was significantly higher than that of their male counterparts (P < 0.001).

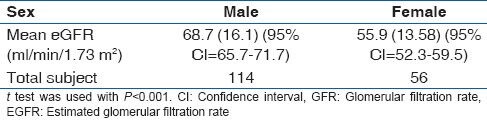

Table 4 shows comparison of mean eGFR between male and female subjects. The mean eGFR in the male subjects was 68.7 (16.1) ml/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI = 65.7-71.7), while that in the female subjects was 55.9 (13.6) ml/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI = 52.3-59.5).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean GFR between male and female subjects

The mean values of eGFR between the male and female subjects were significantly different (P < 0.001).

Discussion

This study was intended to estimate the prevalence of CKD in a retired Nigerian population. In 2002, Kidney Disease Outcomes Qualitative Initiative of the National Kidney Foundation defined CKD as either kidney damage, exemplified by proteinuria, or a decreased function, i.e., GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for 3 or more months.[11] Scholars have used either criterion to define CKD in earlier publications.[21,22,23] eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was used in defining CKD in this study.

The key findings in the study are as follows:

Prevalence of CKD in the general population was 43.5%. This is in agreement with the 44% reported by Stevens et al.[12] on Kidney Early Evaluation Program and NHANES subjects in the USA. Interestingly, their study recruited subjects aged 65 years and above, making them closely age matched with our participants. From Netherland, Brugts et al.[24] in 2005 reported a prevalence of 44.9% among adult subjects. Furthermore, Takahashi et al.[25] in 2010 reported a prevalence of 26.7% among elderly Japanese. The lower prevalence in these subjects may be due to differences in environmental and cultural factors. In an article in 2009, Afolabi et al.[18] recorded a prevalence of 20.4% among adult subjects on routine visits to a general practice clinic in south west Nigeria. However, their population was significantly younger than ours.

All the subjects with CKD in this study belong to Stage 3. The range of eGFR values in our subjects with CKD, ranged from 31 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. This is similar to the findings of many previous authors on the same subject, including Chadban et al.[3] whose Australian subjects with CKD were mostly in Stage 3. The third NHANES also found most American adults with CKD belonged to Stage 3.[9]

Prevalence of CKD was slightly higher in non-elderly subjects in this present study. This finding is not consistent with the observation of most authors on the subject including a 2009 study by Flessner et al.[26] reporting on prevalence of CKD among African American subjects. Hemmelgarn et al.[27] in 2006 published data from Alberta, Canada, showing an annual decline in GFR in elderly subjects, even in those without obvious CKD risk factors. The same observation was made in 2004 by Garg et al.[28] in seniors requiring long-term care in Ontario, Canada.

However, the reported difference in prevalence between the two groups in this present study was not statistically significant. There was also a very slight difference in age between the two groups studied, making them almost within the same age bracket.

Prevalence of CKD was significantly higher in female subjects than their male counterparts. This finding is consistent with several other studies in different continents; North America;[9,29] Europe[30] and Asia.[2]

Conclusion

Prevalence of CKD among apparently healthy retired Nigerian subjects is quite high. The implications of this are obvious. More aggressive preventive measures, targeting known risk factors, need to be put in place in order to reverse this trend.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by the Ebreime Foundation for the elderly and physically challenged a Non-Governmental Organization. The objective, intentions and available funds of the sponsor were the main determinants of the number of people recruited and data collected.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was sponsored by the Ebreime Foundation for the elderly and physically challenged.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J, Wildman RP, Gu D, Kusek JW, Spruill M, Reynolds K, et al. Prevalence of decreased kidney function in Chinese adults aged 35 to 74 years. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2837–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chadban SJ, Briganti EM, Kerr PG, Dunstan DW, Welborn TA, Zimmet PZ, et al. Prevalence of kidney damage in Australian adults: The AusDiab kidney study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S131–8. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070152.11927.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viktorsdottir O, Palsson R, Andresdottir MB, Aspelund T, Gudnason V, Indridason OS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease based on estimated glomerular filtration rate and proteinuria in Icelandic adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1799–807. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otero A, Gayoso P, Garcia F, de Francisco AL EPIRCE study group. Epidemiology of chronic renal disease in the Galician population: Results of the pilot Spanish EPIRCE study. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;68:S16–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirillo M, Laurenzi M, Mancini M, Zanchetti A, Lombardi C, De Santo NG. Low glomerular filtration in the population: Prevalence, associated disorders, and awareness. Kidney Int. 2006;70:800–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Register COR. Vol. 1. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2001. Report. Dialysis and Renal Transplantation. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, Chavers BM, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, et al. Excerpts from the US renal data system 2009 Annual Data Report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:S1–420. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.009. A6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1–12. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manjunath G, Tighiouart H, Coresh J, Macleod B, Salem DN, Griffith JL, et al. Level of kidney function as a risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes in the elderly. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1121–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens LA, Li S, Wang C, Huang C, Becker BN, Bomback AS, et al. Prevalence of CKD and comorbid illness in elderly patients in the United States: Results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:S23–33. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:659–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oyediran AB, Akinkugbe OO. Chronic renal failure in Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med. 1970;22:41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akinsola W, Odesanmi WO, Ogunniyi JO, Ladipo GO. Diseases causing chronic renal failure in Nigerians – A prospective study of 100 cases. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1989;18:131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mabayoje M, Bamgboye E, Odutola T, Mabadeje A, editors. Chronic Renal Failure at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital: A 10-year review. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:1851–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alebiosu CO, Ayodele OO, Abbas A, Olutoyin AI. Chronic renal failure at the Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2006;6:132–8. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2006.6.3.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afolabi MO, Abioye-Kuteyi AE, Arogundade FA, Bello IS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a Nigerian family practice population. S Afr Fam Pract. 2009;51:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agaba EI, Wigwe CM, Agaba PA, Tzamaloukas AH. Performance of the Cockcroft-Gault and MDRD equations in adult Nigerians with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:635–42. doi: 10.1007/s11255-008-9515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abefe SA, Abiola AF, Olubunmi AA, Adewale A. Utility of predicted creatinine clearance using MDRD formula compared with other predictive formulas in Nigerian patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009;20:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higashiyama A, Watanabe M, Kokubo Y, Ono Y, Okayama A, Okamura T, et al. Relationships between protein intake and renal function in a Japanese general population: NIPPON DATA90. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(Suppl 3):S537–43. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai E, Horio M, Iseki K, Yamagata K, Watanabe T, Hara S, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the Japanese general population predicted by the MDRD equation modified by a Japanese coefficient. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2007;11:156–63. doi: 10.1007/s10157-007-0463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duru OK, Vargas RB, Kermah D, Nissenson AR, Norris KC. High prevalence of stage 3 chronic kidney disease in older adults despite normal serum creatinine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0850-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brugts JJ, Knetsch AM, Mattace-Raso FU, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Renal function and risk of myocardial infarction in an elderly population: The Rotterdam Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2659–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi S, Okada K, Yanai M. The Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) of Japan: Results from the initial screening period. Kidney Int Suppl. 2010;77:S17–23. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flessner MF, Wyatt SB, Akylbekova EL, Coady S, Fulop T, Lee F, et al. Prevalence and awareness of CKD among African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:238–47. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemmelgarn BR, Zhang J, Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Larsen E, Ghali WA, et al. Progression of kidney dysfunction in the community-dwelling elderly. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2155–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg AX, Papaioannou A, Ferko N, Campbell G, Clarke JA, Ray JG. Estimating the prevalence of renal insufficiency in seniors requiring long-term care. Kidney Int. 2004;65:649–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown WW, Peters RM, Ohmit SE, Keane WF, Collins A, Chen SC, et al. Early detection of kidney disease in community settings: The Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:22–35. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nitsch D, Felber Dietrich D, von Eckardstein A, Gaspoz JM, Downs SH, Leuenberger P, et al. Prevalence of renal impairment and its association with cardiovascular risk factors in a general population: Results of the Swiss SAPALDIA study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:935–44. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]