Abstract

Men are more likely to die of cancer, heart disease, or diabetes at younger ages than women – a reality that is compounded by the reluctance of men to use healthcare services. In addition to reduced life expectancy, men can also expect to live fewer healthy years than their female counterparts. As gynecologists and obstetricians have led the women’s health movement in addressing gender-specific gaps in care, urologists are well-poised to take on a leadership role to advocate for, and address, men’s health initiatives.

Overall perspective

The women’s health movement has been a strong force in healthcare planning for the past 2 decades, addressing significant gaps in healthcare delivery, research, advocacy and policy. In contrast, there has been less focus on equally important issues related to men’s health, even though mortality rates are consistently higher among men than women.

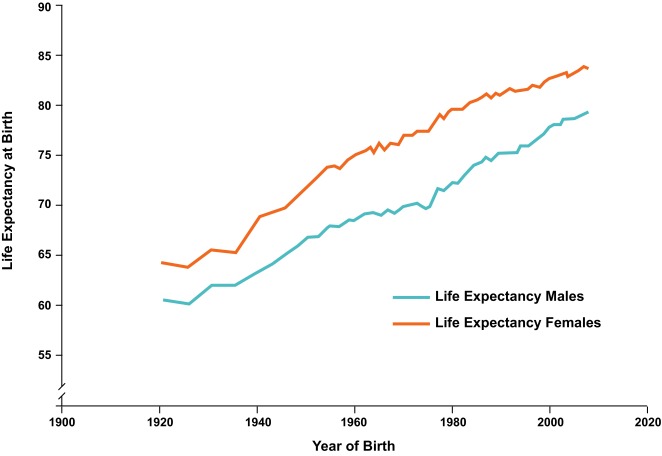

Canadian men, on average, can expect to live for 4 fewer years than women.1 Life expectancy data for British Columbia from the 1920s to the present day show a steady increase in life expectancy for both sexes, thanks to improvements that have percolated through society (i.e., labour laws, safety legislation, smoking cessation, seatbelts and environmental campaigns). Though the gender gap is gradually narrowing, women are still consistently living, on average, longer than men (Fig. 1).2 Part of the issue may be the fact that, in our culture, men are not conditioned to see their health as a priority. Unhelpful stereotypes of independence, risk taking and “the strong silent type” make it difficult to engage in positive health behaviour. An alternative explanation may also be found in the biological reality of the impact of the Y chromosome on the male body and the influence of testosterone on human (and almost all other species) human behaviour.

Fig. 1.

Life expectancy from birth in British Columbia. Taken from Bilsker et al.2

A number of biologic, social and environmental factors contribute to this gap in average life expectancy between the sexes, and there are several particular causes causes of early life loss. Cardiovascular disease is known to strike men more often and earlier than women.3 Some proposed factors contributing to this disparity include poor nutritional habits, such as lower consumption of fruits and vegetables and higher salt intake,3–5 poorer anger management,6 and a higher likelihood of being overweight.2 A potential cardioprotective effect of estrogen has been hypothesized to account for part of the disparity in cardiovascular disease between men and women;7,8 however, further research is needed to determine the role of estrogen in preventing heart disease. Death by suicide is also higher among men than women.9,10 Men are 3 to 4 times more likely to carry out suicide, with the highest rates being among middle-aged men.11 Reasons for this have been attributed to a greater willingness to use lethal methods, a reluctance to talk about emotional distress or seek help for it, higher rates of alcohol use, and a greater tendency to move quickly from thought to action. Males are generally considered to be higher risk-takers than females. Indeed, motor vehicle accidents account for a high proportion of deaths among men in their late teens and 20s. As well, men may be exposed to increased risk of death due to occupational incidents. In particular, northern residents account for 35% of all workplace deaths in British Columbia, and males account for nearly 94% of occupational deaths and the vast majority of hospitalizations resulting from workplace incidents.12

In addition to reduced life expectancy, men also have lower rates of health expectancy – the number of years a person can expect to live in good health.13 As a society, we have grown accustomed to the disappearance of millions of Canadian men from our daily lives – not only from death, but also from illnesses that have rendered them too frail to contribute to their full potential. The reality is that Canadian men spend their later years in poorer health than their female counterparts. It is debatable whether this variability between the sexes in different countries and localities is an issue of inequity, masculinity or biological inevitability.

Many chronic health conditions in men (estimated at 70%) can be attributed to lifestyle and are potentially preventable. In most cultures, most men have been raised to adopt a masculine role, with a focus on independence, fearlessness and strength. As a result, men are generally less likely than women to seek help, or to acknowledge weakness or vulnerability, with negative health consequences.14 It is generally acknowledged that men are less likely than women to use healthcare services, with an estimated 80% of men refusing to see a physician until they are convinced by their spouse or partner to do so.15,16

Men’s health initiatives in Canada

Although several provinces support specific men’s health initiatives, such as prostate cancer awareness, depression or exercise/diet, none of the provincial or territorial health ministries promote any overarching strategies or initiatives to target men’s health directly. In 2002, Quebec commissioned the Comité de travail en matière de prévention et d’aide aux hommes (Working committee for prevention and assistance to men); this group released a report focusing on male health and social services. In 2004, the Committee made a number of recommendations to the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services. These recommendations included the development of specific strategies for addressing suicide, where men are considered a priority client; and the development of public awareness campaigns related to men’s health, focusing on the need for men to conduct self-examinations of their testicles, as well as prostate cancer screening and prevention. They also recommended that services offered by the Ministry be adapted towards the needs of men.

Until 2007, no federal government actions directly targeted men’s health. This changed when the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) sponsored the first national Canadian conference on men’s health and held a “Boy’s and Men’s Health” Seed Grant competition, which led to the funding of 9 proposals. Awareness campaigns such as “Movember” have helped to raise awareness of men’s health issues within the mainstream population. Movember has become one of the largest sources of funding for prostate cancer in the world, and has recently expanded to increase awareness around male mental health.

In 2009, the Male Health Initiative of BC was launched as an umbrella initiative to facilitate educational collaboration, broad spectrum research and the gathering, production and dissemination of best practices or standards of care. The initiative also enabled the advocacy of men’s health issues at all levels of government. Most recently, in June 2014, the non-profit Canadian Men’s Health Foundation (CMHF) was established to inspire men to live healthier lives. The goal of the foundation is to raise social awareness of largely preventable health problems and to enable men, and their families to value men’s health by providing them with information and healthy lifestyle programs that will motivate them to truly hear, absorb and act on it. This is achieved through programs, such as online health risk assessment tools and ongoing awareness campaigns based on modern communications research, focus groups as well as collaboration with other healthcare societies and associations to assist them to activate their men’s health campaigns. The Foundation’s first national awareness campaign, “don’t change much,” includes websites, social media, advertising and news coverage directed at 30- to 50-year-old men, their partners and families. A Canadian Men’s Health Week now takes place annually in the days leading up to Father’s Day.

Where does the urologist fit as a male health specialist?

Across a man’s lifespan, the urologist plays a vital role in the management of men’s health issues – dealing with voiding abnormalities and urinary tract infections in the early years; erectile and reproductive issues throughout the reproductive years; testosterone deficiency, prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in later years; and other genitourinary cancers that can occur throughout the lifespan of a male. In addition to conditions with a urologic presentation, many general male health issues have a urologic impact. Obesity has been linked to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).17–19 Smoking is a known risk factor for bladder cancer.20 In many cases, sexual dysfunction is a portal to the early detection of cardiovascular disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, hypogonadism and bone problems. Therefore, when a man presents with erectile dysfunction, the urologist has an opportunity to investigate possible underlying causes, including cardiovascular disease and endocrine dysfunction. For the man who presents to the urologist with decreased levels of energy and libido suggestive of hypogonadism, depression might also be considered as a differential diagnosis. Analogous to the role that obstetricians and gynecologists have assumed in women’s health, urologists have a unique opportunity to act as champions of men’s health and are well-positioned to communicate important prevention messages. Urologists recognize the negative effects of early lifestyle behaviours, such as smoking and poor nutrition, on male health and the risk of later genitourinary disorders. The urologist therefore has the opportunity to affect positive change through early intervention, such as smoking cessation and weight loss counselling, as well as through education, risk assessment, awareness and prevention campaigns.

Conclusion

With the growing acknowledgement of the need for a gender-specific focus on the health needs of men, the urologist is uniquely poised to assume a leadership role in the coordination and collaboration of male health issues – from “cradle to grave.” By acting as a gateway to the health system for men who might otherwise be reluctant to seek care, urologists can help organize standards of care and best practices for men’s health.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Goldenberg has received honoraria from Abbott Canada, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, and Eli Lilly in the past 2 years.

References

- 1.United Nations Statistics Division. Social indicators. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind/default.htm. Accessed June 17, 2014.

- 2.Bilsker D, Goldenberg L, Davison J. A roadmap to men’s health: Current status, research, policy and practice. Vancouver, BC: Men’s Health Initiative; 2010. www.aboutmen.ca/application/www.aboutmen.ca/asset/upload/tiny_mce/page/link/A-Roadmap-to-Mens-Health-May-17-2010.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health Agency of Canada. Tracking heart disease and stroke in Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2009/cvd-avc/pdf/cvd-avs-2009-eng.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fruit and vegetable consumption among adults-United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leigh JP, Fries JF. Associations among healthy habits, age, gender, and education in a sample of retirees. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1993;36:139–55. doi: 10.2190/ELMX-WXGJ-7HQN-AN18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chida Y, Steptoe A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: A meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:936–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi BG, McLaughlin MA. Why men’s hearts break: cardiovascular effects of sex steroids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:365–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wizemann TM, Pardue M-L. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does sex matter? Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Committee on Understanding the Biology of Sex and Gender Differences, Board on Health Sciences Policy. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10028.html. Accessed June 17, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hee Ahn M, Park S, Ha K, et al. Gender ratio comparisons of the suicide rates and methods in Korea, Japan, Australia, and the United States. J Affect Disord. 2012;142:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milner A, McClure R, De Leo D. Globalization and suicide: an ecological study across five regions of the world. Arch Suicide Res. 2012;16:238–49. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.695272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada. Definitions and data sources. Statistics Canada health indicators. 2001. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-221-x/01201/4149362-eng.htm. Accessed June 17, 2014.

- 12.Sharpe A, Hardt J. Five deaths a day: Workplace fatalities in Canada, 1993–2005. Ottawa: Centre for the Study of Living Standards; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics. Global health indicators part 2. 2010. http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS10_Full.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2014.

- 14.Courtenay WH. Key determinants of the health and the well-being of men and boys. Int J Men’s Health. 2003;2:1–27. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0201.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juel K, Christensen K. Are men seeking medical advice too late? Contacts to general practitioners and hospital admissions in Denmark 2005. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:111–3. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldenberg SL. Men’s Health Initiative of British Columbia: Connecting the dots. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;39:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Kim JC, Lee JY, et al. Effects of obesity on lower urinary tract symptoms in Korean BPH patients. Asian J Androl. 2009;11:663–8. doi: 10.1038/aja.2009.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammarsten J, Hogstedt B, Holthuis N, et al. Components of the metabolic syndrome-risk factors for the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1998;1:157–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammarsten J, Hogstedt B. Clinical, anthropometric, metabolic and insulin profile of men with fast annual growth rates of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Blood Press. 1999;8:29–36. doi: 10.1080/080370599438365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anton-Culver H, Lee-Feldstein A, Taylor TH. The association of bladder cancer risk with ethnicity, gender, and smoking. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:429–33. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90072-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]