We read with great interest the article by Tremosini et al in Gut 1, which prospectively validated the use of a panel of three antibodies (glypican 3, heat shock protein 70 and glutamine synthetase) for the histopathological diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. According to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology2, hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) are classified into HCC not otherwise specified (HCC-NOS) which accounts for the vast majority of HCC, fibrolamellar HCC (fHCC), scirrhous HCC, spindle cell variant HCC, clear cell HCC and pleomorphic HCC. While many studies including the one from Tremosini and colleagues restrict their focus on HCC-NOS, we decided to study fHCC in more depth. fHCC is a rare tumor with limited clinical information available. Current data suggest that demographic attributes of fHCC cases are very different from cases of HCC-NOS not only in terms of gender but also with regard to the presence for the existence of pre-existing liver disease3–5. Unlike most HCCs, fHCCs typically arise in the absence of liver cirrhosis6, 7.

Because of differences between HCC-NOS and fHCC, many clinical trials specifically exclude patients with fHCC8. However, the tumor is commonly treated similarly to HCC-NOS in the absence of better knowledge.

With the aim of increasing existing knowledge of fHCC, we examined data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program for fHCC. Cases included in this report were reported by the SEER 18 registries. Cases were diagnosed with fHCC between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010.

Gender, age and reported frontline treatment, including radiofrequency ablation, resection, and transplantation were examined. To protect confidentiality, counts with fewer than 10 cases are not displayed. Radiofrequency ablation, resection, and transplant cases were combined as “treatments with curative intent” in survival analyses. Analyses were performed using SEER*Stat software version 7.1.0 (IMS Incorporated, Silver Spring, MD). Analyses calculated chi-squared tests using SAS v 9.2 (Cary, NC) to estimate P-values for differences in both tumor size and receipt of surgery by histology.

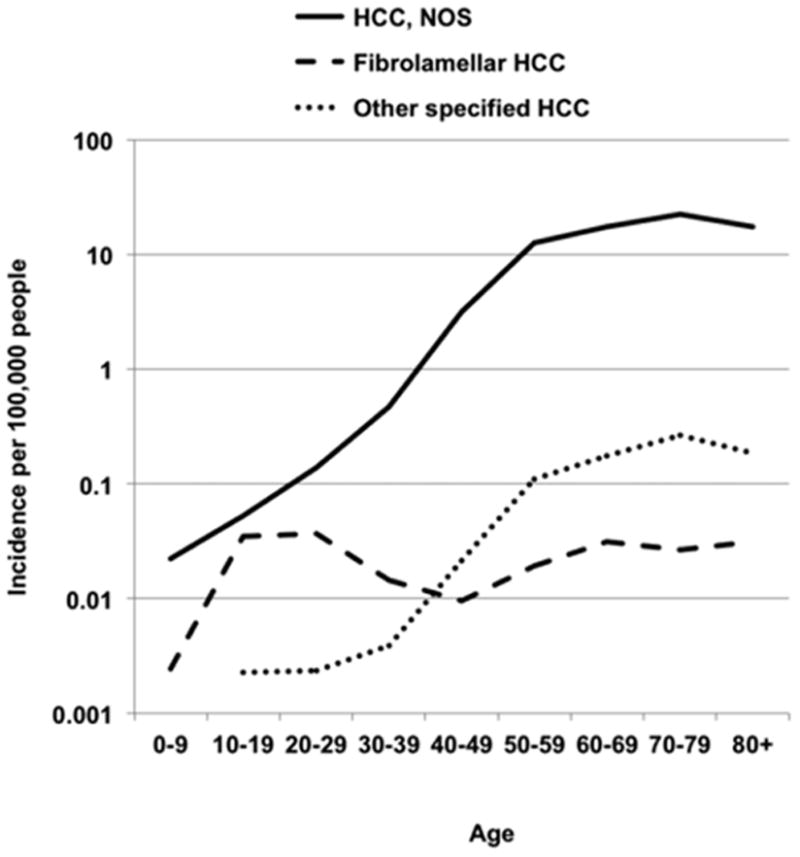

Between 2000 and 2010, a total of 46,392 cases of HCC-NOS, 339 cases of clear cell HCC, 19 cases off HCC and 118 cases of the remaining 3 HCC subtypes were reported. For all histologies, including fHCC, a higher proportion of cases were male with HCC-NOS having the highest male to female case ratio (3.2), and fHCC having the lowest ratio (1.7). Unexpectedly, age-specific incidence analysis, revealed two age-specific peaks for patients with fHCC, one among young persons between the ages of 10–30 years and a second among persons aged 60–69 years (Figure 1). For the other HCC types combined, the age specific rates and peak incidence (70–79 years) were very similar to those of HCC-NOS. fHCC patients experienced significantly better 5-year relative survival (34%) than patients with HCC-NOS (16%) (Table 1). In summary this case series of 191 fHCC patients, which is the largest to date, revealed the new finding of the existence of two age-specific peaks for fHCC, one at younger ages and one at more typical ages for HCC-NOS. Furthermore, while five year survival was significantly better among fHCC cases than HCC-NOS cases, no difference in survival was found by HCC type among cases who received a curative treatment procedure (surgery, radiofrequency ablation and transplantation) as a first line treatment.

Figure 1.

Age-specific hepatocellular carcinoma incidence rates per 100,000 by tumor histology, SEER 18 registries, 2000–2010

Table 1.

5-year relative survival by surgery, fHCC and HCC-NOS cases by age group, SEER 18 2000–2010*

| HCC, Not Otherwise Specified | Fibrolamellar HCC | P‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Group | N | 5-year relative survival, CI† | N | 5-year relative survival, CI† | |

| All Cases | 880 | 25.0% (21.7%, 28.5%) | 115 | 40.3% (29.9%, 50.5%) | |

| RFA, Resection, Transplant | 9,047 | 51.1% (49.6%, 52.5%) | 88 | 56.8% (43.5%, 68.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Non-curative treatment§ | 34,665 | 6.2% (5.8%,6.6%) | 94 | 7.4% (2.2%, 16.9%) | |

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), resection and transplants combined due to small counts for specific fibrolamellar therapy as treatment with curative intent

Results for other types of surgery that are not potentially curative were not reported.

CI= 95% confidence interval

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA), resection, or transplantation versus no surgery by Fibrolamellar versus HCC, NOS

Non-curative treatment include transarterial chemoembolization, radiation and systemic therapies

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, National Cancer Institute contracts with SEER registries.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- NOS

not otherwise specified

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Footnotes

Contributorship: KM, AD, MPM, TFG and SA: study concept, TE and SA primary data screen, TE, SA and TG data analysis, TG and SE wrote manuscript, all authors approved final manuscript.

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tremosini S, Forner A, Boix L, et al. Prospective validation of an immunohistochemical panel (glypican 3, heat shock protein 70 and glutamine synthetase) in liver biopsies for diagnosis of very early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2012;61:1481–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, et al., editors. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3. Geneva: World Health Organzation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Is fibrolamellar carcinoma different from hepatocellular carcinoma? A US population-based study. Hepatology. 2004;39:798–803. doi: 10.1002/hep.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuda K. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma including fibrolamellar and hepato-cholangiocarcinoma variants. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:401–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig JR, Peters RL, Edmondson HA, et al. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver: a tumor of adolescents and young adults with distinctive clinico-pathologic features. Cancer. 1980;46:372–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800715)46:2<372::aid-cncr2820460227>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakar S, Burgart LJ, Batts KP, et al. Clinicopathologic features and survival in fibrolamellar carcinoma: comparison with conventional hepatocellular carcinoma with and without cirrhosis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1417–23. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagorney DM, Adson MA, Weiland LH, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatoma. Am J Surg. 1985;149:113–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(85)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]