Everything should be kept as simple as possible, but no simpler.

—Albert Einstein1

Since its estimated first description >500 years ago by Leonardo da Vinci,2 the bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) has progressively built a reputation; initially, as a curious valvular phenotype with a tendency to develop obstruction and insufficiency. In more contemporary times, however, the BAV is recognized as underlying almost 50% of isolated severe aortic stenosis cases requiring surgery,3 and has been extensively associated with ominous outcomes such as bacterial endocarditis and aortic dissection.4 These associations, coupled with the high prevalence of BAV in humans,5 have prompted investigative efforts into the condition, which although insightful, have generated more questions than answers. This review describes our current knowledge of BAV, but, more importantly, it highlights knowledge gaps and areas where basic and clinical research is warranted. Our review has 2 sections. The first section outlines the multifaceted challenge of BAV, our current understanding of the condition, and barriers that may hamper the advancement of the science. The second section proposes a roadmap to discovery based on current imaging, molecular biology, and genetic tools, recognizing their advantages and limitations.

Bicuspid Aortic Valve: A Multifaceted Challenge

A Condition Characterized by Variable Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation and consequences of BAV in humans are exceedingly heterogeneous, with few clinical or molecular markers to predict associated complications.4,6 BAV can be diagnosed at any stage during a lifetime, from newborns7 to the elderly,8 and in the setting of variable clinical circumstances. Some are benign circumstances such as auscultatory abnormalities or incidental echocardiographic findings in otherwise healthy patients8; other circumstances are morbid, such as early severe aortic valve dysfunction, premature congestive heart failure, and thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAAs).8,9 Life-threatening circumstances include bacterial endocarditis and acute aortic dissection.8–11 These complications may present within a wide age range and may constitute the clinical debut of an otherwise previously healthy patient with unidentified bicuspid status.10,11 In the community, auscultatory abnormalities account for ≈60% to 70% of diagnostic echocardiograms for BAV.8,10 These diverse presentations hamper coordinated screening efforts for BAV. In addition, the failure of clinicians to recognize a systolic ejection murmur or click, typically best heard at the apex and aortic area,12,13 or to appreciate the significance of aortic valve and aorta disease in the family history, may hinder the prompt diagnosis of BAV.

A Valvuloaortopathy With Varied Phenotypes and Unpredictable Outcomes

Given the high incidence of BAV dysfunction requiring surgical intervention and the high incidence of associated TAA formation8–10,14–18 (Table), the BAV condition should be viewed as a valvuloaortopathy, at least from the nosological perspective. Phenotypically, all possible combinations and degrees of cusp fusion (with or without the presence of a fibrous ridge [raphe] between the conjoined cusp) can be observed by echocardiography (Figures 1 and 2). The resulting 2 aortic cusps are usually asymmetrical with 3 identifiable sinuses of Valsalva, and only 5% are estimated to be symmetrical,19 each cusp occupying 180 degrees of the annular circumference. A symmetrical BAV without raphe is often referred to as a true BAV and has only 2 identifiable sinuses of Valsalva (Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement).

Table. Contemporary Clinical Outcomes in BAV.

| Contemporary Clinical Outcomes BAV Studies* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Study Features, Clinical Outcomes |

Michelena et al8 | Tzemos et al9 | Michelena et al10 | Davies et al14† | Russo et al15 | Borger et al16‡ | McKellar et al17 | Girdauskas et al18§ |

| Publication year | 2008 | 2008 | 2011 | 2007 | 2002 | 2004 | 2010 | 2012 |

| Clinical setting | Community, population-based | Tertiary referral center | Community, population-based | Tertiary referral center | Tertiary referral center | Tertiary referral center | Tertiary referral center | Tertiary referral center |

| Inclusion characteristics | Minimal BAV dysfunction | Any BAV dysfunction | Any BAV dysfunction | Any BAV dysfunction with aortic aneurysm (mean baseline diameter 4.6 mm) | Status post AVR | Status post AVR | Status post AVR | Status post isolated AVR with aortic aneurysm (mean baseline diameter 4.6 mm) |

| N | 212 | 642 | 416 | 70 | 50 | 201 | 1286 | 153 |

| Baseline age, y, mean±SD | 32±20 | 35±16 | 35±21 | 49 | 51±12 | 56±15 | 58±14 | 54±11 |

| Follow-up years, mean±SD | 15±6 | 9±5 | 16±7 | 5 | 20±2 | 10±4 | 12±7 | 12±3 |

| Survival | 90% at 20 y | 96% at 10 y | 80% at 25 y | 91% at 5 y | ≈40% at 15 y | 67% at 15 y | 52% at 15 y | 78% at 15 y |

| Heart failure | 7% at 20 y | 2% | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Aortic valve surgery | 24% at 20 y | 21% | 53% at 25 y | 68% | – | – | – | – |

| Reason for aortic valve surgery | AS 67% AR 15% | AS 61% AR 27% | AS 61% AR 29% | – | – | – | – | – |

| Endocarditis | 2% | 2% | 2% | – | 4% | 2% | – | – |

| Aneurysm formation (definition, mm) | 39% (>40 mm) | 45% (>35 mm) | 26% at 25 y (≥45 mm) | – | – | 9% (≥50 mm) | 10% (≥50 mm) | 3% (≥50 mm) |

| Aortic surgery (for aneurysm) | 5% at 20 y | 7% | 9% | 73% | 6% | 9% | 1% | 3% |

| Aortic dissection | 0% at 20 y | 1% | 0.5% at 25 y | 9% | 10% at 20 y | 0.5% | 1% at 15 y | 0% |

AR indicates aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; AVR, aortic valve replacement; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; and SD, standard deviation.

Outcomes reported as percentage only were not reported within Kaplan-Meier survival analyses. Survival in the first 3 studies (Michelena,8 Tzemos,9 and Michelena10) was not different than that of the general population. Survival in the McKellar17 study was inferior to that of the general population, and the rest of the studies were not compared with the general population.

This study compared BAV patients with aneurysms versus tricuspid aortic valve patients with aneurysms. The incidence of aortic dissection was the same for both groups with superior survival in BAV patients and both groups dissecting at similar aortic diameters.

This study suggested that patients with aortic dimension ≥45 mm at the time of AVR should have the aorta concomitantly repaired; the basis of the current recommendations.

This study included consecutive patients with isolated AVR performed for aortic stenosis only. However, 21 patients with predominant dilatation of the root (mean diameter, 44 mm) and severe aortic regurgitation who underwent AVR were followed in parallel for a mean of 10 years and 2 acute dissections occurred.

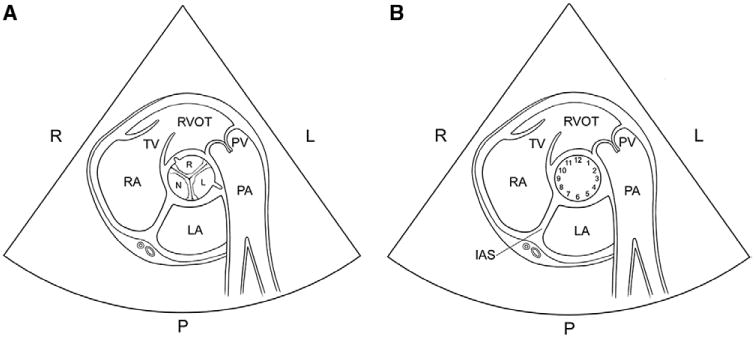

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram anatomy of the aortic valve. A, Schematic of the normal tricuspid aortic valve in the parasternal short-axis view. The right coronary cusp (small R) is anterior and positioned between the tricuspid valve and pulmonic valve. The left coronary cusp (small L) is posterior and related to the left atrium, whereas the noncoronary cusp (N) is related to the interatrial septum (IAS). Note the origin of the coronary arteries at the right and left cusps. The anatomic relations of each cusp relative to adjacent structures are critical in determining which 2 cusps are fused. B, The aortic valve annular circumference can be visualized like the face of a clock. Bicuspid valves are classified as type 1 (right-left coronary cusp fusion, 70%–80% prevalence) if the commissures are at 4 to 10, 5 to 11, or 3 to 9 o'clock and the anatomy relative to adjacent structures suggests right-left fusion, type 2 (right-noncoronary cusp fusion, 20%–30% prevalence) if the commissures are at 1 to 7 or 12 to 6 o'clock and the anatomy relative to adjacent structures suggests right-nonfusion, and type 3 (left-noncoronary cusp fusion, 1% prevalence) if the commissures are at 2 to 8 o'clock and the anatomy relative to adjacent structures suggests left-nonfusion. It is important to note that there can be an overlap between the clock positions, and, thus, it is critical to know the anatomic relations of each cusp. Identification of the raphe can be invaluable in determining the conjoined cusp. Identification of the origin of the left and right coronary arteries (as shown) may also be invaluable. LA indicates left atrium; large L, left side of the patient; large R, right side of the patient; P, posterior aspect of the heart; PA, pulmonary artery; PV, pulmonic valve; RA, right atrium; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; and TV, tricuspid valve.

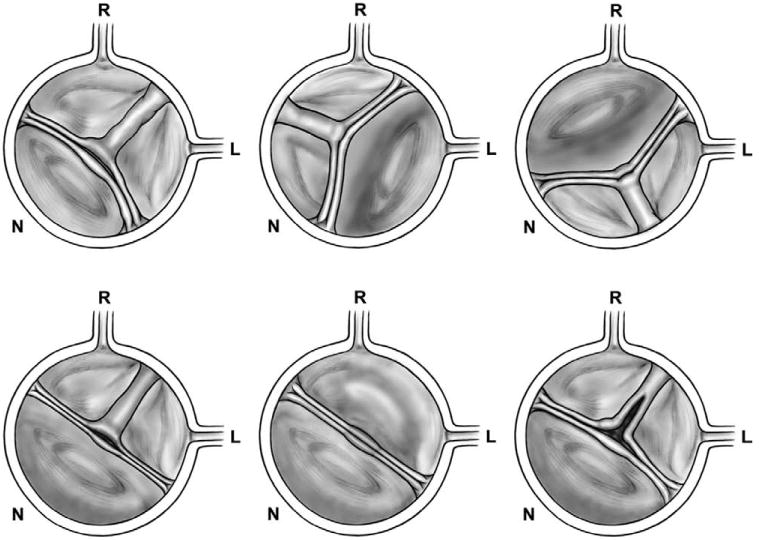

Figure 2.

Schematic of BAV phenotypes as seen by transthoracic echocardiogram. The standard imaging technique for BAV diagnosis is transthoracic echocardiogram. The diagnosis is based on parasternal long- and short-axis imaging of the aortic valve. The schematics presented represent the parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view. Bicuspid valves are classified as type 1 (right-left coronary cusp fusion), type 2 (right-noncoronary cusp fusion), and type 3 (left-noncoronary cusp fusion). The figure demonstrates BAV phenotypes. Top left shows a type 1 BAV (commissures at 10 and 5 o'clock) with complete raphe, asymmetrical (the nonfused cusp [noncoronary] is smaller than the conjoined anterior cusp). Top middle shows a type 2 BAV (commissures at 1 and 7 o'clock) with complete raphe and asymmetrical (the nonfused cusp [left] is larger than the conjoined cusp). Top right shows a type 3 BAV (shown with commissures at 2 and 8 o'clock, but could be 1 and 7 o'clock) with complete raphe, asymmetrical (the nonfused cusp [right] is larger than the conjoined one). Bottom left shows a symmetrical type 1 BAV with complete raphe. Bottom middle shows a symmetrical type 1 BAV without raphe (true BAV). Bottom right shows a type 1 BAV with incomplete raphe, partially fused. BAV indicates bicuspid aortic valve; L, left cusp; N, noncoronary cusp; and R, right cusp.

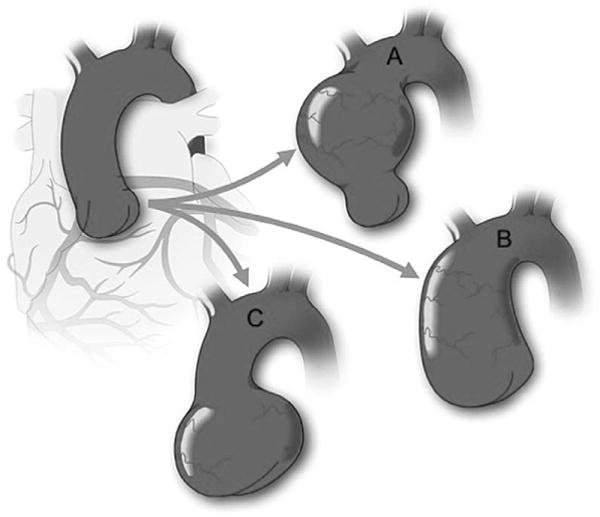

Even if normally functioning or minimally dysfunctional (as determined by echocardiography), the 2 cusps of most BAVs exhibit asymmetrical systolic excursion with marked bending strain in systole,20 high stress in the raphal area of the conjoined cusp,21 uneven systolic flow patterns, and intrinsic morphological stenosis.22 The ascending aorta (including the root [sinuses of Valsalva] and the tubular-ascending portion) also displays a spectrum of aneurysmal phenotypes (Figure 3),23–25 tubular-ascending aorta dilatation being the most common phenotype (60%–70% of dilated aortas)with the fastest growing rate in adults (≈0.4–0.6 mm/y),25,26 irrespective of BAV morphology and function.25 However, there is also a predominant sinus of Valsalva dilatation phenotype that is less common (≈25% of dilated aortas) and associated with type 1 (right-left cusp fusion) BAV morphology24 and male sex.25 This root phenotype has been associated with faster tubular-ascending aorta dilatation,26 and aortic regurgitation is, in turn, related to faster root dilatation.25 In addition, half of BAV patients with severe aortic regurgitation exhibit a significant loss of medial elastic aortic fibers,27 and a root phenotype with aortic regurgitation has recently been associated with a higher risk of aortic dissection in a limited BAV sub-group.18 Thus, we hypothesize that a root phenotype and aortic regurgitation could represent higher TAA-risk BAV subsets. Importantly, the dilatation rates are variable, independent of the BAV phenotype, and, for the most part, unpredictable in BAV patients.25 The underlying mechanisms responsible for such varied BAV-associated valvuloaortic phenotypes remain unknown, and, despite the aforementioned valvular pathophysiologic insights, why a BAV becomes stenotic, another regurgitant, another is associated with aortic dilatation, and yet another remains functional throughout a lifetime, remains fundamentally unknown and unpredictable, a critical knowledge gap that remains unresolved since its first description by Roberts >40 years ago.28 More concerning is the fact that there is only scarce insight as to why a few unfortunate BAV patients will incur aortic dissection in their lifetime but many will not.10 Indeed, available clinical tools attempting to risk stratify BAV patients for aortic catastrophes (ie, aortic size) are only modestly useful because catastrophic aortic events may occur in patients with less-than-severe enlargement, below danger-zone cutoffs,29 whereas patients with aortic diameters well above these cutoffs may never dissect or dissect late.10,30

Figure 3.

Schematic of variable aorta phenotypes encountered in BAV. Figure demonstrates the different aortic dilatation patterns that may occur in BAV in comparison with a normal aorta (Top left). Although the most common portion to dilate is the tubular ascending aorta (A), the entire ascending aorta may be affected, including sinuses of Valsalva and tubular aorta with sinotubular junction effacement (B). There is a subgroup of BAV patients who exhibit dilatation of the sinuses of Valsalva preferentially (C). This pattern is associated with type 1(right-left fusion) BAV and male sex.20,24 BAV indicates bicuspid aortic valve.

Innocent Bystander or Primary Disease?

Although the BAV phenotype presents most commonly in isolation in adults (only 15% associated congenital heart abnormalities versus 50% in young children),7,10 BAV relates to several congenital and genetic disorders with cardiovascular manifestations, often associated with congenital left-sided obstructive lesions (ie, coarctation of the aorta, Shone complex),7 ventricular septal defect,31 and syndromic conditions (ie, Turner, Loeys-Dietz), and familial TAA and dissection disease due to smooth muscle α-actin (ACTA2) gene mutations, as well.4,32,33 Despite the evidence of an autosomal dominant pattern of BAV inheritance with variable expression and incomplete penetrance in families,34,35 and the identification of mutations in NOTCH1 (associated with BAV and valvular calcium-deposition derepression), as well,36 and GATA5 (associated with BAV and aortopathy) in rare families with BAVs,37 the genetic causes and their potential clinical implications for the majority of BAV patients remain largely unknown. In light of this genetic and developmental conundrum, is it possible that the BAV may be a by-product of a more widespread genetic alteration involving the aorta and other structures of the developing heart such that the BAV is sometimes merely an innocent bystander? Or are there more restricted alterations limited to the aortic valve, with distinct types of primary BAV disease: a primary valvular type wherein a BAV is the main feature, and, thus, the most probable complication is the need for aortic valve replacement (AVR), and another primary type wherein a valvuloaortopathy predominates with potential aortic valve dysfunction and TAA formation with augmented aortic dissection risk? Or is there a complex form of BAV disease more often uncovered in childhood because of its symptomatic presentation and another simple form more often uncovered in adults because of its paucity of symptoms? Indeed, BAV is frequently associated with complex conditions leading to diagnosis in childhood (ie, Shone complex),38 whereas it is found mostly in isolation (with or without TAA) when diagnosed in adults,8 although some complex features such as aortic coarctation may be carried into adulthood. Patterns and rates of aortic dilatation may also differ between pediatric and adult populations,25 and aortic dissection is extremely rare in young BAV children.39,40 Answers to these questions are far from being a mere academic curiosity, given the direct patient care impact on risk stratification that their elucidation would provide.

Natural History of BAV: What Do We Know?

Prospective, long-term clinical follow-up of individuals with BAV diagnosed at birth by routine screening would be ideal in decoding the natural history of BAV and its complications. However, massive echocardiographic screening of entire populations at birth and subsequent very long-term (ie, lifelong) follow-up are not feasible from resource and time perspectives. Retrospective identification and phenotyping of BAV patients with prospective follow-up is thus an important clinical research strategy.

Our knowledge of the contemporary BAV natural history stems from population-based and tertiary-referral–based retrospective studies (Table) where the BAV condition began at echocardiographic diagnosis,8–10 with the inevitable exclusion of BAV patients who never came to medical attention (remaining undiagnosed) and the rejection of uncertain BAV diagnoses.10 The notion of natural history is also tainted by pharmacological interventions and guideline-driven surgeries for life-threatening events or their prevention, best illustrated by prophylactic aorta surgical repair recommended by guidelines when the ascending aortic diameter is ≥50 mm (recently changed to >55 mm by new, 2014 AHA/ACC guidelines40a), or ≥45 mm if concomitant AVR is being performed,41 where the former represents a non–evidence-based extrapolation of Marfan syndrome guidelines and the latter is supported by 2 observational studies16,30 (importantly, there are no randomized trials to inform the timing of prophylactic surgery for any thoracic aneurysmal disease). Therefore, the information gathered by clinical research is the clinical history of BAV instead of natural history. Nonetheless, mean follow-up times up to 16 years and a maximum of 25 to 30 years have been attained,10 and important clinical history observations have emerged from contemporary studies (Table). After mean follow-ups ranging from 9 to 16 years, it is apparent that, despite increased risks of early aortic valve dysfunction, premature congestive heart failure, AVR, endocarditis, TAA formation, aortic dissection (Table), and complications related to accompanying ailments (ie, aortic coarctation), the 25-year survival of BAV patients after echocardiographic diagnosis is not different from that of the general population. This is explained in part by the young age at BAV diagnosis (mean, 32–35 years) and the low risk associated with contemporary AVR, and also by the fact that the incidence of life-threatening complications is low.10 Indeed, the incidence of aortic dissection in all BAV patients across 3 decades (1980–2010) has been estimated to be 8 times higher than in the general population, but still remains exceedingly low at 0.03% per year (up to 0.4%–0.5% in patients with aneurysms and >50 years of age).10 This low incidence is only partially explained by prophylactic aorta repair, because guidelines did not appear until the late 1990s,42–44 and current specific diameter cutoffs for BAV were not published until 200641 and continue to be controversial in both medical45 and surgical circles.46

In older BAV patient cohorts, however, overall survival is likely affected; a large retrospective study of 1286 BAV patients followed after AVR found that survival was not different from that of the general population up to 7 years, but was decreased at 15 years17 (Table). Given that people are now living longer, this older post-AVR patient group deserves further study, both to confirm these findings and to elucidate their basis.

Bacterial endocarditis exhibits a predilection for men and is also uncommon, but highly morbid, affecting ≈2% of the BAV cohorts studied (Table), and, although complicated by abscess formation more commonly than tricuspid aortic valves, it does not determine higher mortality during hospitalization and at 5 years follow-up11 for BAV patients. This is likely the result of BAV patients with endocarditis being younger and having fewer comorbidities than tricuspid valve patients despite exhibiting higher endocarditis-related complications. Thus, endocarditis in age-matched BAV patients could indeed carry a higher mortality, a hypothesis that requires further investigation.

BAV: Victim of Parsimony?

In medicine, diagnostic parsimony advocates that the source of multiple symptoms should be adjudicated to only 1 disorder: “among competing hypothesis, favor the simplest one.”47 This exercise is usually exhausted before considering the prospect of multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms occurring in the same patient. Clinical parsimony in BAV is best exemplified by the assumption that BAV-related aortopathy is clinically equivalent to the aortopathy of Marfan syndrome, which has led to the extrapolation of elective surgery aortic diameter cutoffs from Marfan guidelines to BAV guidelines.41 There are pathological similarities between BAV aortas and the aortas of patients with Marfan syndrome, a condition whose genetic basis48 and natural history49 have been definitively elucidated. These similarities include the fragmentation loss of elastic fibers, decreased numbers of smooth muscle cells, and increased deposition of proteoglycans in the medial layer of the aorta, termed medial degeneration.50,51 Interestingly, however, 100% of Marfan patients with severe aortic regurgitation and TAA exhibit a severe loss of medial elastic fibers in comparison with 47% of similar BAV patients.27 Other similarities include an imbalance of extracellular matrix–degradating enzymes (metalloproteinases) and their inhibitors that has been described for both entities.50–52 These biological similarities do not have clinically equivalent implications, however, as evidenced by significantly decreased life expectancy due to aortic dissection49 in patients with Marfan syndrome who do not undergo prophylactic aortic surgery. The average age of death in these patients is only 32 years, and acute aortic dissection and its complications account for 80% of these deaths.49 In contrast, the mean age of BAV patients at entry into the first contemporary BAV clinical history study was also 32 years of age,8 with a subsequent 20-year risk of elective aneurysm surgery of only 5%, 20-year survival identical to that of the general population, and no documented aortic dissections (Table). In addition, despite BAV being ≈100 times more common than Marfan,53 the International Registry of Aortic Dissection has shown that the Marfan syndrome still accounts for 50% of aortic dissections in patients <40 years of age (versus 9% for BAV).54 Moreover, the risk of aortic dissection during pregnancy is significantly higher with Marfan syndrome55 than with BAV.56 Nonetheless, aortic dilatation (>40 mm) was present in <10% of pregnant BAV women in the study by McKellar et al56 on BAV and pregnancy. Thus, the risk of dissection in pregnant BAV patients with dilated aortas remains unknown. A large BAV registry may offer sufficient aortic diameter variability to study this population. Finally, despite faster progression of aortic dilatation in BAV patients with aneurysms in comparison with tricuspid aortic valve patients with aneurysms,14,25 the incidence of aortic catastrophes was reported as equal14 (Table), with both groups dissecting at similar aortic diameters, although more BAV patients underwent elective aorta repair. These data suggest that the clinical outcome of the BAV-aortopathy may resemble more that of the general population with aneurysms than the aortopathy of Marfan syndrome, a notion that has been recognized in the new ACC/AHA valvular heart disease management guidelines40a by increasing the elective aorta repair cut-off to 55 mm.

The notion of a common pathogenic pathway leading to BAV and its complications is also challenged by clinical observations. It is fundamentally unknown why a child develops severe BAV dysfunction,57 an adult with moderate BAV dysfunction develops aortic dissection,10 and a healthy 89-year-old individual is incidentally found to have a minimally dysfunctional BAV.8 It is thus apparent that undiscovered, complex genetic and environmental pathogenic factors are at play, and that pathogenic parsimony is not the answer. This concept will be critical when deciphering the underpinnings of BAV stenosis. Recent evidence suggests an active inflammatory process with angiogenesis,58 fibrosis, and calcification resembling bone formation involved in the pathogenesis of tricuspid aortic valve stenosis.58 Are these the same molecular pathways involved in BAV stenosis? Why does BAV stenosis occur decades earlier than tricuspid aortic valve stenosis? Is mechanical stress more important in the pathogenesis of BAV stenosis? What role does genetic predisposition to calcification play in BAV stenosis?

BAV: Victim of Compartmentalization?

Failure to recognize its heterogeneity has made BAV a casualty of the efforts to explain its complications from oversimplified and rigid viewpoints. For example, there is considerable debate as to whether hemodynamic alterations related to BAV or a genetic defect leading to aortic disease is the cause of TAA in BAV patients.6 Data are available to support both etiologies. A genetic defect driving the BAV-associated aortopathy is supported by the fact that unaffected first-degree relatives of BAV patients may exhibit aneurysmal aortic disease.59 Additionally, tricuspid aortic valve patients with the same degree of aortic stenosis have a lower incidence of TAA than BAV patients.60 Similarly, although the aortic dilatation rate may decrease after AVR,61 AVR does not halt aortic dilatation progression in BAV,17,62 and late post-AVR aortic dissections do occur15,17 (Table). It is nevertheless evident that an association between overt BAV dysfunction and TAA formation exists,10,61 but is it causal? Recent studies also suggest that fluid hemodynamics and aortic wall stress in the BAV aorta are abnormal even in the absence of echocardiographically defined overt valvular dysfunction,63,64 which not only represents proof of concept that a normally functioning BAV is intrinsically dysfunctional,22 but also suggests that hemodynamic-induced stress likely contributes to aortic dilatation.64 Although transcriptional, protein, and histopathologic alterations have been characterized in aortas of BAV patients,50–52,65 it remains to be elucidated whether these biochemical imbalances occur spontaneously or result from altered cellular mechanics and gene expression in response to strain and shear stress in the BAV aorta,65 or both.

The BAV has also been compartmentalized from the clinical outcomes perspective, particularly when studied in pediatric versus adult populations. The controversy surrounding the clinical significance of specific BAV phenotypes exemplifies this issue. Although some cross-sectional studies in adults suggest associations between type 2 BAV and valvular stenosis, and between type 1 BAV and regurgitation,66,67 adult cohort populations show no evidence of associations between BAV phenotypes and clinical outcomes (ie, AVR).8–10 Conversely, pediatric populations exhibit an association between type 2 BAV (right-noncoronary fusion) and accelerated valve dysfunction (both stenosis and regurgitation) leading to valve intervention.7,57 Thus, the clinical significance of BAV phenotypes may differ between adults and children, which may explain why the prevalence of the right-noncoronary phenotype is higher in children (30%–40%)7,68 than in adults (≈20%),8,10 probably reflecting a natural selection process whereby phenotypes less prone to dysfunction persist into adulthood. At the same time, many patients with type 2 BAV will not develop significant valvular dysfunction, suggesting that factors other than just phenotype dictate the degree of valvular dysfunction. Identifying these factors would be the first step toward determining who with BAV is at risk for valvular complications, and may begin to shed light on the molecular mechanisms responsible for valvular dysfunction, a critical initial step for targeted therapies.

Current Clinical Approach to Adult BAV Patients

Although derived mostly from consensus, after a diagnosis of BAV is made, the following management principles should be observed: (1) Echocardiographic screening of first-degree family members is recommended to rule out BAV and aortopathy.69 (2) Aortic coarctation must be ruled out by echocardiography or computed tomography/magnetic resonance. (3) The echocardiographic monitoring interval of BAV function should follow current valvular and echocardiography appropriateness guidelines.41,70 (4) Appropriate dental hygiene must be recommended for endocarditis prevention. (5) Surgical intervention timing for BAV dysfunction should follow current valvular guidelines.41 (6) If root or ascending aorta dilatation is detected by echocardiography (ie, ≥40 mm), confirmation of size by computed tomography/magnetic resonance is recommended. If no significant measurement disparities are found between techniques, a repeat echocardiography at 6 months is recommended; and, if aortic size remains stable, without a family history of aortic dissection, annual aortic imaging is then recommended. (7) Aggressive treatment of hypertension and tobacco cessation must be pursued in BAV patients with aortopathy.69 (8) Elective intervention for ascending aneurysms is indicated when the aorta measures ≥55 mm (if no family history of aortic dissection exists), when it measures ≥45 mm and concomitant AVR is being performed, or when dilatation rate is ≥0.5 cm/year.40a,69 (9) In selected patients with aortic dilatation and family history of thoracic aortic disease, genetic consultation and testing may be useful in determining timing of elective aortic intervention. (10) BAV without aortopathy and no valve dysfunction should be screened every 3 to 5 years with echocardiography to rule out the development of aortopathy/ valvulopathy, and patients who have undergone isolated AVR must continue yearly root and ascending aorta imaging to rule out the development or worsening of dilatation. (11) After surgical replacement of the ascending aorta, the arch and descending thoracic aorta should be monitored every 3 to 5 years with computed tomography/magnetic resonance.

Rising to the Challenge: A Road Map to Discovery

Advancing the Science

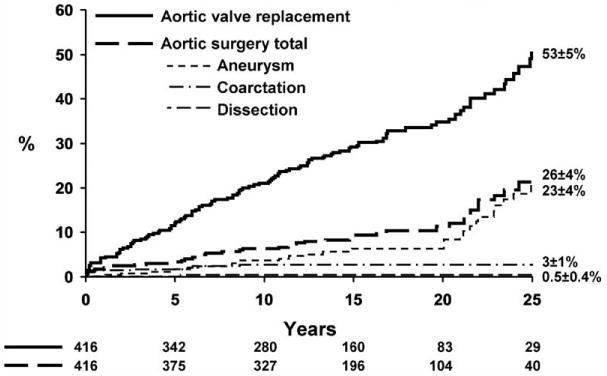

To advance the science, it is essential to identify clinical targets. Although life-threatening aortic complications are the most feared, the largest population-based outcomes study with the longest follow-up10 showed that severe BAV dysfunction driven by valvular stenosis and requiring AVR is, by far, the most common morbidity of BAV patients, with >50% of patients requiring AV R within 25 years of their initial diagnosis (Figure 4, Table). Furthermore, AVR occurs a mean of 18 years earlier in BAV patients than in those with a tricuspid valve,8 usually within the productive years of life. The second most common morbidity is the development of significant aorta dilatation (≥45 mm), which occurs in >25% of BAV patients 25 years after BAV diagnosis (age at BAV diagnosis and aneurysm diagnosis, 35±21 years and ≈50±17 years, respectively).10 These observations should focus efforts of basic science on the genetic and pathological mechanisms of BAV stenosis and TAA formation. Accurate classification of BAV phenotypes, coupled with functional aortic flow imaging and the identification of genetic risk variants and circulating biomarkers, could identify patients at high risk for accelerated valvular calcification and TAA formation, as well.

Figure 4.

Twenty-five year risk of aortic valve replacement versus surgery of the aorta. Kaplan-Meier risk of AVR and aorta surgery (all causes) 25 years after definitive diagnosis of BAV. After 25 years of follow-up, the risk of undergoing AVR doubles that of aortic surgery. Based on data from Michelena et al.10 AVR indicates aortic valve replacement; and BAV, bicuspid aortic valve.

Regarding currently available therapies for BAV, contemporary observations also mandate clinical research to improve surgical repair of the noncalcified purely regurgitant BAV.71 Despite the prolapse of the conjoined cusp being considered the premier pathomechanism involved in BAV regurgitation, it is now recognized that the prolapse of the nonfused cusp is also prevalent. In addition, the spatial orientation of the true commissures and the size of the aortoventricular junction, as well, are predictors of repair durability.71 The development of selection criteria and safe platforms for transcatheter aortic valve replacement72,73 is critical, because BAV is present in >20% of octogenarians with severe aortic valve stenosis,74 and BAV patients may also carry a high open AVR risk. Despite the theoretical concern of elliptic deployment of the transcatheter valve in BAV annuli (instead of the ideal circular deployment), and the concern of valve underdeployment,75 transcatheter delivery and the deployment of Edwards-SAPIEN valves72 and Core valves73 in patients with BAV has been proven feasible, but needs further study in large patient cohorts to define the ideal candidates for available platforms and to design new BAV-tailored ones.

Regarding life-threatening clinical targets in BAV (endocarditis and aortic dissection), given their low incidence (Table), it becomes necessary to accrue very large numbers of BAV patients with long-term follow-up, such as in a multicenter, international registry, to identify new factors associated with these complications. The registries should include retrospective patient inclusion as long as BAV diagnosis and phenotype can be confirmed with direct evaluation of previous imaging studies or available pathology.

Parsimony and compartmentalization, but, more importantly, a mere lack of data, are responsible for the current controversy surrounding the indication and timing of elective surgical intervention for the aorta in BAV patients.46,76 For example, conflicting observational studies prompt entirely different positions on the issue of prophylactic aorta repair during AVR15,17,18 (Table), some suggesting radical replacement of all ascending aortas during AVR15 and others a more conservative approach based on aortic size and direct inspection of the aorta during AVR.77,78 It is obvious that aortic size29 (the main tool to stratify the risk of aortic dissection in BAV patients) and evidence of medial degeneration (if it could be determined before catastrophic events)30 are limited risk stratification tools. Traditionally, we have interpreted aortic dissection to be the result of simple mechanical failure,43 directly related to the excess aortic wall tension that severe dilatation imposes. However, aortic dissection is likely the final product of a silent gathering storm whereby mechanical, biological, and genetic influences act in unison.79 This is the only plausible explanation as to why aortic size alone is limited as a risk predictor. Several barriers exist to advancing the science of predicting aortic catastrophes in BAV: (1) Aortic dissection is an uncommon event in BAV.10 (2) Aortic size–based randomization to elective surgery versus no intervention would be unethical. (3) Multiple imaging modalities are capable of measuring the aorta,69 but the reproducibility between modalities is controversial. Some authors report an excellent correlation between aortic measurements by transthoracic echocardiography and computed tomography,80 whereas others report decreased sensitivity for dilatation detection by echocardiography,81 and others show systematic underestimation of diameters by echocardiography in comparison with computed tomography.82 (4) Functional imaging of the aorta is in its infancy, and molecular imaging of the aorta that reflects underlying pathology is not available. (5) Potential areas such as genetic-based and biomarker-based risk stratification, both of which require very large patient numbers, remain unexplored, in part, because of a relative paucity of genetic and other biomarker candidates for BAV complications.

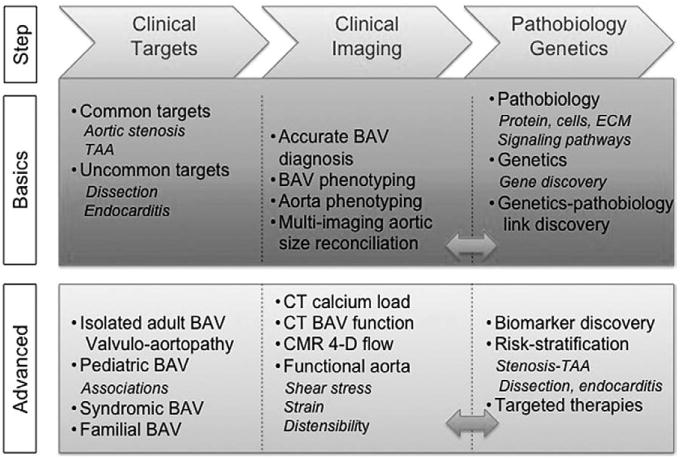

Rising to the aforementioned challenges calls for several general steps. The first step is to recognize that association does not imply causality, but clever interpretation of associations may steer the design of research to elucidate causality and evaluate prophylactic and secondary treatment strategies. The second step is to develop a collaborative multicenter retrospective and prospective BAV patient registry with homogeneous and rigorous entry criteria (ie, accurate BAV diagnosis and phenotyping with exclusion of unclear cases), where state-of-the-art multimodality imaging, pathology, and genotyping tools are used (Figure 5). The third step is to assemble a panel of experts from different specialties to nonparsimoniously reconcile the clinical, imaging (phenotypic and functional), pathobiology, genetic, and management pieces of the puzzle.

Figure 5.

Roadmap for advancing the science. After identifying basic and advanced clinical targets, the critical next steps are precise BAV diagnosis and phenotyping, and accurate aortic size multi-imaging measurement, as well. Advanced imaging allows for additional CT and CMR innovative evaluations. The bidirectional feedback between clinical imaging and pathobiology-genetics (double-headed arrows) leads to biomarker discovery, sophisticated risk stratification, and the development of specific therapies for basic and advanced clinical targets. BAV indicates bicuspid aortic valve; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; ECM, extracellular matrix; and TAA, thoracic aortic aneurysm.

State-of-the-Art Imaging of the BAV and Aorta: An Essential Requirement

Echocardiography

Despite well-recognized transthoracic echocardiographic BAV diagnostic features (Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement) and reasonable phenotyping capability, diagnostic uncertainty may remain in 10% to 15% of patients after echocardiogram.10 This limitation not only affects patient care (ie, unclear bicuspid status), but also hampers phenotypic-genetic association research efforts. In patients with good-quality transthoracic images who do not have dense BAV calcification, diagnostic sensitivity and specificity are >70% and >90%, respectively.83,84 Diagnostic and phenotyping accuracy can be significantly improved with the use of higher-resolution imaging techniques (ie, magnetic resonance, computed tomography, and transesophageal echocardiography), particularly in patients with advanced calcific disease in whom diagnostic accuracy may improve from ≈70% with echocardiography to >90% for magnetic resonance.85,86 When ascertaining aortic dimensions, echocardiography may potentially measure obliquely and not perpendicular to the long axis of the aortic flow, rendering inaccurate measurements. In addition, different measurement protocols (ie, inner-edge to inner-edge versus leading-edge to leading-edge and end-diastolic versus end-systolic) result in systematic measurement variation87 within echocardiography. Furthermore, transthoracic echocardiography measurements of the aortic root are systematically lower than those measured by ECG-gated computed tomography angiography.88 This has important implications with regard to surveillance imaging, because computed tomography angiography should be considered state-of-the-art owing to its higher resolution, but clinical cutoffs for intervention have largely been derived from echocardiography. Another potential risk stratifier that deserves further study in BAV patients is the value of aortic cross-sectional area indexed by height89 or other anthropometric parameters. Nonetheless, echocardiography remains a validated, state-of-the-art imaging modality for the diagnosis, phenotyping, and hemodynamic assessment of aortic valve dysfunction and the initial assessment of the thoracic aorta.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

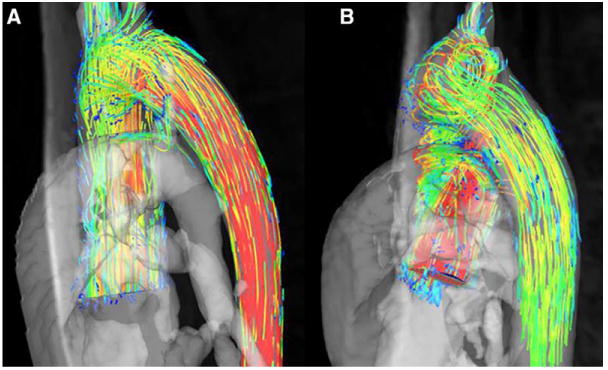

Cardiac MRI (CMR) has gained importance in clarifying questionable BAV diagnoses and imaging the ascending aorta perpendicular to the aortic lumen. More importantly, new CMR techniques have brought us closer to understanding the hemodynamic forces within the ascending aorta in the presence of BAV. Blood flow imaging with 3-dimensional time-resolved, phase-contrast CMR (4-dimensional flow) allows descriptive flow characterization and quantification of aortic wall shear stress, as well63 (Figure 6). Eccentric systolic jets resulting in abnormal right-handed helical ascending aorta flow have been identified in BAV patients, even in normally functioning BAVs with normal aortic diameters.64,90 Furthermore, an increased flow angle (jet eccentricity) was associated with greater aortic growth in BAV patients in a small retrospective cohort,91 suggesting that the quantification of the hemodynamic contribution in BAV aortopathy could become a novel imaging biomarker for risk stratifcation.91 Flow abnormalities appear to depend on BAV phenotype,64,92 but the clinical implication of this observation is unknown. CMR may also shed light on the functional aortopathy by quantifying aortic function with aortic strain, distensibility, and pulse wave velocity, but current results are inconclusive; 1 study showed changes in ascending aortic distensibility in young patients with BAV,93 whereas a larger study including a wide age range of patients could not replicate those findings.64 CMR offers the unique opportunity to transition from anatomic to dynamic imaging of the ascending aorta, assessing its functional properties and blood flow patterns, as well.

Figure 6.

CMR ascending aortic flow patterns in BAV. A, Normal ascending aortic flow pattern in a healthy volunteer. B, Typical ascending aortic flow pattern in a patient with bicuspid aortic valve; helical flow is seen in the ascending aorta, a forward-moving rotational movement of the aortic blood flow. BAV indicates bicuspid aortic valve; and CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

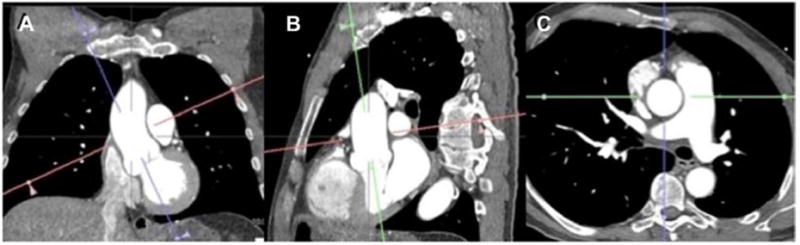

Computed Tomography

Akin to CMR, computed tomography (CT) provides a measurement that is perpendicular to the longitudinal or flow axis of the aorta to correct for the variable geometry of the aorta as it courses through the chest69 (double-oblique measurement technique, Figure 7). A major advantage of CT is its superior spatial resolution in comparison with both echocardiography and CMR. With faster image acquisition, dynamic imaging of the aortic valve is also feasible with temporal resolutions <100 ms,94 which may provide information on BAV function. The aortic valve can be planimetered for area, interrogated for morphology, and the presence and patterns of calcification ascertained. BAV patients tend to have large annuli (ie, >23 mm),25 which may generate discordant less-than-severe aortic stenosis echocardiographic grading with mean gradients of >40 mm Hg and valve areas of >1 cm2.95 A severity-grading tool such as CT-derived aortic valve calcium load may offer an independent platform to reconcile these discrepancies,96 but it has not been studied in BAV patients.

Figure 7.

Double-oblique CTA ascending aorta measurement. Figure demonstrates a coronal multiplanar reformation. An imaging plane longitudinal to the aorta (A) results in a subsequent image depicted in B, through which another plane is aligned longitudinal to the aorta (green) and a plane orthogonal to the latter (red) is also prescribed. The resulting image (C) is a plane that is axial to the ascending aorta at the level of the pulmonary arterial bifurcation. CTA indicates computed tomography angiography.

If headway is to be made in the study of BAV, several imaging research goals must be pursued: (1) CT or MR should be used to diagnose and determine specific BAV phenotypes in patients with unclear echocardiographic evaluation; (2) CT or MR should be pursued for measurement of the entire thoracic aorta when it appears dilated by echocardiography (ie, measures >40 mm) or when echocardiographic mid-distal ascending aorta visualization is limited; (3) determination of the best aorta measurement protocols that reconcile differences between echocardiography, CT, and MR, with standardization of these measurement methods for each technique, with the premise that the gold standard should be CT or MR (higher resolution and optimal cross-sectional acquisition), and the caveat that current clinical cutoffs were mostly derived from echocardiography; (4) long-term imaging and clinical follow-up of a BAV cohort in which the aforementioned imaging was performed, along with baseline MRI–4-dimensional aortic flow data, should be pursued, and DNA and surgical valve/ aorta specimens banked for molecular and genetic studies; and (5) quantification and characterization of calcification patterns of BAVs by CT according to BAV phenotype.

Pathobiology and Genetics: Pathways Toward Individualized Risk Stratification and Care of the BAV Patient

Pathobiology

Previous studies have identified molecular signaling pathways responsible for aortic valve embryological development. The Notch signaling pathway is involved in the formation of the outflow tract and the endocardial-mesenchymal transition, an important process involved in valvulogenesis.97 The development of the semilunar valves is intimately linked to outflow tract septation and aorta/aortic arch remodeling. Neural crest cells participate in the formation of the vascular smooth cells of the ascending aorta, present in the late phase of semilunar valve development.98 The disruption of Notch signaling in mice is associated with defective neural crest cells patterning, unequal aortic valve leaflets with a bicuspid-like morphology and disorganized aortic wall histology.99 These observations suggest a potential signaling pathway abnormality linked to both aortic valve and aorta embryology.

Decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression may be related to BAV formation in mice100 and could modulate valvular mineralization. Also, dysregulation of the transforming growth factor-β pathway in BAV aortas in comparison with tricuspid aortic valve aortas has been suggested.101 In addition to and consistent with the flow abnormalities described by CMR, an asymmetrical pattern of histological abnormalities and nonhomogeneous distribution of biomolecular changes is observed in the ascending aortas of BAV patients.102,103

It is therefore apparent that genetic alterations that lead to altered cellular signaling (ie, Notch, transforming growth factor-β) can cause BAV and associated aortic pathologies, such that establishing the genetic-to-pathology link is critical. The creation of banks of valve and aortic tissue from well-phenotyped patients operated on for aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, and aortic aneurysm will be critical for assessing the gene and protein expression patterns associated with the condition. The selection of appropriate controls for these studies is pivotal; they may include patients undergoing surgery for related conditions but without BAV, for example, those with aortic stenosis and tricuspid aortic valves. Developing animal models of BAV and its associated complications is a challenge, but it remains of crucial importance to deciphering the molecular pathology of BAV. Ultimately, further understanding of BAV at the molecular level may help identify novel markers of complications and targets for medical therapy.

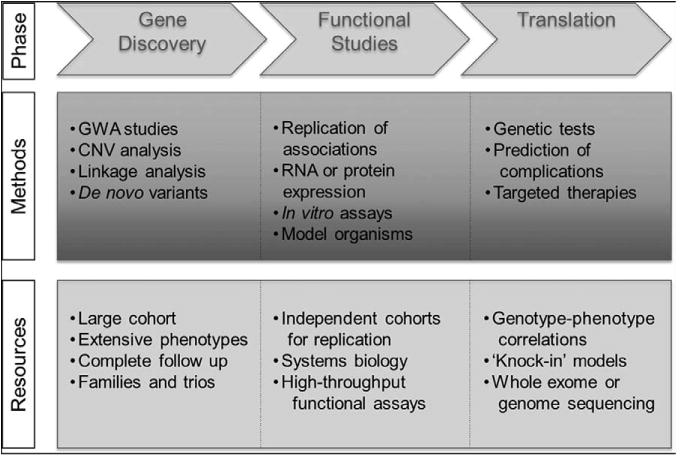

Genetics

The aforementioned marked heterogeneity of BAV poses a major challenge to researchers whose aim is to identify genetic variants that cause BAV or predict BAV-associated complications. To address these challenges, specific goals need to be met. (1) A well-characterized BAV cohort that is followed over time should be established that is sufficiently large to permit association studies that are adequately powered to detect genetic variants with small or moderate effects leading to both BAV and its complications and to examine genetic determinants of rare outcomes or subtypes of BAV. Therefore, thousands of cases will be required to identify substantial genetic contributors. (2) To minimize bias due to misclassification, all cases in a BAV registry should be evaluated by experts in the field with the use of stringent, uniform criteria and standardized measurements. Adjudication of valve phenotypes and clinical end points by the appropriate imaging and outcomes cores will prevent misclassification and ensure the validity of findings. (3) Follow-up should be sufficiently long to capture the complications of BAV that may be slow to develop, such as aortic stenosis, with prioritized enrollment of patients who have not yet experienced complications. In most cases, this will require follow-up periods of >10 years; therefore, the inclusion of retrospectively identified patients will be critical, as long as accurate phenotype adjudication and standardized measurements are applied to current or previous available imaging. (4) A control cohort of imaging-negative, tricuspid aortic valve individuals should be recruited and followed in parallel with the BAV cohort. To minimize the confounding of associations due to systematic differences between cases and controls, it will be essential to compare BAV findings in appropriately matched tricuspid valve individuals who are equally well characterized and drawn from the same populations as the BAV cases. Associations can be distorted by ascertainment bias if convenience control groups, who may not have received the same level of diagnostic scrutiny, are acquired from registries or sample banks. (5) Families with inherited BAV should be prioritized for enrollment, because these families are more likely to have rare variants in single genes that can be identified by using whole exome or whole genome sequencing. Genes that were discovered to be altered in families with BAV, such as NOTCH1, are also found to be altered in sporadic cases and can provide a starting point for understanding the genetic architecture of BAV. Finally, as genetic risk factors for BAV and its complications are identified, the registry should be the foundation for clinical trials of gene-based tests or therapies for BAV patients who are at high risk for adverse outcomes to develop targeted medical therapies and to inform surgical decision making based on their individualized genetic risk profiles (Figure 8). Because many different genetic variants are likely to contribute to BAV outcomes, we envision a multicenter registry as a rich and continuous source of future genetic studies.

Figure 8.

The roadmap to translate genetic discoveries into clinical applications. A key priority is to identify candidate genes for BAV-associated phenotypes, a critical step in the development of translational therapies. First, suggestive findings from family-based or case-control studies must be independently validated in separate groups of BAV cases. The roles of candidate genes in valve development or disease can then be assessed by using in vitro or animal models, which may facilitate the development of interventions that target these genes and biological pathways. Finally, genetic tests or therapies need to be tested in randomized clinical trials of BAV patients. Knockout animal models include tissue-specific and whole organism deletion of genes, and knock-in models are generated by introducing a specific human sequence variant into a similar gene in a model organism. BAV indicates bicuspid aortic valve; CNV, copy number variant; and GWA, genome-wide association.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://circ.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007851/-/DC1

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Einstein A. On the method of theoretical physics: The Herbert Spencer lecture, delivered at Oxford 10 June 1933. Oxford University Press; 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braverman AC, Güven H, Beardslee MA, Makan M, Kates AM, Moon MR. The bicuspid aortic valve. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2005;30:470–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts WC, Ko JM. Frequency by decades of unicuspid, bicuspid, and tricuspid aortic valves in adults having isolated aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, with or without associated aortic regurgitation. Circulation. 2005;111:920–925. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155623.48408.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cedars A, Braverman AC. The many faces of bicuspid aortic valve disease. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;34:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carro A, Teixido-Tura G, Evangelista A. Aortic dilatation in bicuspid aortic valve disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2012;65:977–981. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandes SM, Sanders SP, Khairy P, Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Lang P, Simonds H, Colan SD. Morphology of bicuspid aortic valve in children and adolescents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1648–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelena HI, Desjardins VA, Avierinos JF, Russo A, Nkomo VT, Sundt TM, Pellikka PA, Tajik AJ, Enriquez-Sarano M. Natural history of asymptomatic patients with normally functioning or minimally dysfunctional bicuspid aortic valve in the community. Circulation. 2008;117:2776–2784. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzemos N, Therrien J, Yip J, Thanassoulis G, Tremblay S, Jamorski MT, Webb GD, Siu SC. Outcomes in adults with bicuspid aortic valves. JAMA. 2008;300:1317–1325. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michelena HI, Khanna AD, Mahoney D, Margaryan E, Topilsky Y, Suri RM, Eidem B, Edwards WD, Sundt TM, 3rd, Enriquez-Sarano M. Incidence of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. JAMA. 2011;306:1104–1112. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Sorel C, Thuny F, Casalta JP, Riberi A, Jeu A, Gouriet F, Collart F, Caus T, Raoult D, Habib G. Clinical characteristics and outcome of infective endocarditis in adults with bicuspid aortic valves: a multicentre observational study. Heart. 2010;96:1723–1729. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.189050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leech G, Mills P, Leatham A. The diagnosis of a non-stenotic bicuspid aortic valve. Br Heart J. 1978;40:941–950. doi: 10.1136/hrt.40.9.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs WR. Ejection clicks. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd. chap 28. Boston, MA: Butterworths; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies RR, Kaple RK, Mandapati D, Gallo A, Botta DM, Jr, Elefteriades JA, Coady MA. Natural history of ascending aortic aneurysms in the setting of an unreplaced bicuspid aortic valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1338–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russo CF, Mazzetti S, Garatti A, Ribera E, Milazzo A, Bruschi G, Lanfranconi M, Colombo T, Vitali E. Aortic complications after bicuspid aortic valve replacement: long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:S1773–S1776. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04261-3. discussion S1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borger MA, Preston M, Ivanov J, Fedak PW, Davierwala P, Armstrong S, David TE. Should the ascending aorta be replaced more frequently in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKellar SH, Michelena HI, Li Z, Schaff HV, Sundt TM., 3rd Long-term risk of aortic events following aortic valve replacement in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1626–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girdauskas E, Disha K, Raisin HH, Secknus MA, Borger MA, Kuntze T. Risk of late aortic events after an isolated aortic valve replacement for bicuspid aortic valve stenosis with concomitant ascending aortic dilation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:832–837. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs137. discussion 837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabet HY, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, Daly RC. Congenitally bicuspid aortic valves: a surgical pathology study of 542 cases (1991 through 1996) and a literature review of 2,715 additional cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:14–26. doi: 10.4065/74.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katayama S, Umetani N, Hisada T, Sugiura S. Bicuspid aortic valves undergo excessive strain during opening: a simulation study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conti CA, Della Corte A, Votta E, Del Viscovo L, Bancone C, De Santo LS, Redaelli A. Biomechanical implications of the congenital bicuspid aortic valve: a finite element study of aortic root function from in vivo data. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:890–896. 896.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robicsek F, Thubrikar MJ, Cook JW, Fowler B. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve: how does it function? Why does it fail? Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazel SS, Mallidi HR, Lee RS, Sheehan MP, Liang D, Fleischman D, Herfkens R, Mitchell RS, Miller DC. The aortopathy of bicuspid aortic valve disease has distinctive patterns and usually involves the transverse aortic arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:901–907. 907.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaefer BM, Lewin MB, Stout KK, Gill E, Prueitt A, Byers PH, Otto CM. The bicuspid aortic valve: an integrated phenotypic classification of leaflet morphology and aortic root shape. Heart. 2008;94:1634–1638. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Detaint D, Michelena HI, Nkomo VT, Vahanian A, Jondeau G, Sarano ME. Aortic dilatation patterns and rates in adults with bicuspid aortic valves: a comparative study with Marfan syndrome and degenerative aortopathy. Heart. 2014;100:126–134. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Della Corte A, Bancone C, Buonocore M, Dialetto G, Covino FE, Manduca S, Scognamiglio G, D'Oria V, De Feo M. Pattern of ascending aortic dimensions predicts the growth rate of the aorta in patients with bicuspid aortic valve. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts WC, Vowels TJ, Ko JM, Filardo G, Hebeler RF, Jr, Henry AC, Matter GJ, Hamman BL. Comparison of the structure of the aortic valve and ascending aorta in adults having aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis versus for pure aortic regurgitation and resection of the ascending aorta for aneurysm. Circulation. 2011;123:896–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts WC. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. A study of 85 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1970;26:72–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90761-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pape LA, Tsai TT, Isselbacher EM, Oh JK, O'Gara PT, Evangelista A, Fattori R, Meinhardt G, Trimarchi S, Bossone E, Suzuki T, Cooper JV, Froehlich JB, Nienaber CA. Eagle KA; International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Investigators. Aortic diameter >or = 5.5 cm is not a good predictor of type A aortic dissection: observations from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Circulation. 2007;116:1120–1127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eleid MF, Forde I, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Suri RM, Schaff HV, Enriquez-Sarano M, Michelena HI. Type A aortic dissection in patients with bicuspid aortic valves: clinical and pathological comparison with tricuspid aortic valves. Heart. 2013;99:1668–1674. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hor KN, Border WL, Cripe LH, Benson DW, Hinton RB. The presence of bicuspid aortic valve does not predict ventricular septal defect type. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:3202–3205. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeys BL, Chen J, Neptune ER, Judge DP, Podowski M, Holm T, Meyers J, Leitch CC, Katsanis N, Sharifi N, Xu FL, Myers LA, Spevak PJ, Cameron DE, De Backer J, Hellemans J, Chen Y, Davis EC, Webb CL, Kress W, Coucke P, Rifkin DB, De Paepe AM, Dietz HC. A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:275–281. doi: 10.1038/ng1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milewicz DM, Guo DC, Tran-Fadulu V, Lafont AL, Papke CL, Inamoto S, Kwartler CS, Pannu H. Genetic basis of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections: focus on smooth muscle cell contractile dysfunction. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:283–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huntington K, Hunter AG, Chan KL. A prospective study to assess the frequency of familial clustering of congenital bicuspid aortic valve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1809–1812. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cripe L, Andelfinger G, Martin LJ, Shooner K, Benson DW. Bicuspid aortic valve is heritable. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garg V, Muth AN, Ransom JF, Schluterman MK, Barnes R, King IN, Grossfeld PD, Srivastava D. Mutations in NOTCH1 cause aortic valve disease. Nature. 2005;437:270–274. doi: 10.1038/nature03940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Padang R, Bagnall RD, Richmond DR, Bannon PG, Semsarian C. Rare nonsynonymous variations in the transcriptional activation domains of GATA5 in bicuspid aortic valve disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escárcega RO, Michelena HI, Bove AA. Bicuspid aortic valve: a neglected feature of Shone's complex? Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35:186–187. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zalzstein E, Hamilton R, Zucker N, Diamant S, Webb G. Aortic dissection in children and young adults: diagnosis, patients at risk, and outcomes. Cardiol Young. 2003;13:341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fikar CR, Fikar R. Aortic dissection in childhood and adolescence: an analysis of occurrences over a 10-year interval in New York State. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E23–E26. doi: 10.1002/clc.20383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, 3rd, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM, 3rd, Thomas JD. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. [Accessed May 2, 2014]; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000031. published online ahead of print March 3, 2014. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2014/02/27/CIR.0000000000000031.full.pdf+html. [DOI]

- 41.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, de Leon AC, Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, O'Gara PT, O'Rourke RA, Otto CM, Shah PM, Shanewise JS, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Fuster V, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College Of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006;114:e84–e231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonow RO, Carabello B, de Leon AC, Edmunds LH, Jr, Fedderly BJ, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, McKay CR, Nishimura RA, O'Gara PT, O'Rourke RA, Rahimtoola SH, Ritchie JL, Cheitlin MD, Eagle KA, Gardner TJ, Garson A, Jr, Gibbons RJ, Russell RO, Ryan TJ, Smith SC., Jr ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. Executive Summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease) J Heart Valve Dis. 1998;7:672–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Hammond GL, Mandapati D, Darr U, Kopf GS, Elefteriades JA. What is the appropriate size criterion for resection of thoracic aortic aneurysms? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:476–491. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70360-X. discussion 489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kouchoukos NT, Dougenis D. Surgery of the thoracic aorta. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1876–1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guntheroth WG. A critical review of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association practice guidelines on bicuspid aortic valve with dilated ascending aorta. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma S, Yanagawa B, Kalra S, Ruel M, Peterson MD, Yamashita MH, Fagan A, Currie ME, White CW, Wai Sang SL, Rosu C, Singh S, Mewhort H, Gupta N, Fedak PW. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice patterns in surgical management of bicuspid aortopathy: a survey of 100 cardiac surgeons. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:1033–1040.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilliard AA, Weinberger SE, Tierney LM, Jr, Midthun DE, Saint S. Clinical problem-solving. Occam's razor versus Saint's Triad. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:599–603. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps031794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dietz HC, Cutting GR, Pyeritz RE, Maslen CL, Sakai LY, Corson GM, Puffenberger EG, Hamosh A, Nanthakumar EJ, Curristin SM. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature. 1991;352:337–339. doi: 10.1038/352337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murdoch JL, Walker BA, Halpern BL, Kuzma JW, McKusick VA. Life expectancy and causes of death in the Marfan syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:804–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197204132861502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nataatmadja M, West M, West J, Summers K, Walker P, Nagata M, Watanabe T. Abnormal extracellular matrix protein transport associated with increased apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells in Marfan syndrome and bicuspid aortic valve thoracic aortic aneurysm. Circulation. 2003;108(suppl 1):II329–II334. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087660.82721.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fedak PW, Verma S, David TE, Leask RL, Weisel RD, Butany J. Clinical and pathophysiological implications of a bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2002;106:900–904. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027905.26586.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ikonomidis JS, Jones JA, Barbour JR, Stroud RE, Clark LL, Kaplan BS, Zeeshan A, Bavaria JE, Gorman JH, 3rd, Spinale FG, Gorman RC. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and endogenous inhibitors within ascending aortic aneurysms of patients with bicuspid or tricuspid aortic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1028–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sundt TM., 3rd Replacement of the ascending aorta in bicuspid aortic valve disease: where do we draw the line? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(6 suppl):S41–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.053. discussion S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Januzzi JL, Isselbacher EM, Fattori R, Cooper JV, Smith DE, Fang J, Eagle KA, Mehta RH, Nienaber CA, Pape LA International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Characterizing the young patient with aortic dissection: results from the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elkayam U, Ostrzega E, Shotan A, Mehra A. Cardiovascular problems in pregnant women with the Marfan syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:117–122. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-2-199507150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McKellar SH, MacDonald RJ, Michelena HI, Connolly HM, Sundt TM., 3rd Frequency of cardiovascular events in women with a congenitally bicuspid aortic valve in a single community and effect of pregnancy on events. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandes SM, Khairy P, Sanders SP, Colan SD. Bicuspid aortic valve morphology and interventions in the young. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2211–2214. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dweck MR, Boon NA, Newby DE. Calcific aortic stenosis: a disease of the valve and the myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1854–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loscalzo ML, Goh DL, Loeys B, Kent KC, Spevak PJ, Dietz HC. Familial thoracic aortic dilation and bicommissural aortic valve: a prospective analysis of natural history and inheritance. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1960–1967. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keane MG, Wiegers SE, Plappert T, Pochettino A, Bavaria JE, Sutton MG. Bicuspid aortic valves are associated with aortic dilatation out of proportion to coexistent valvular lesions. Circulation. 2000;102(19 suppl 3):III35–III39. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim YG, Sun BJ, Park GM, Han S, Kim DH, Song JM, Kang DH, Song JK. Aortopathy and bicuspid aortic valve: haemodynamic burden is main contributor to aortic dilatation. Heart. 2012;98:1822–1827. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yasuda H, Nakatani S, Stugaard M, Tsujita-Kuroda Y, Bando K, Kobayashi J, Yamagishi M, Kitakaze M, Kitamura S, Miyatake K. Failure to prevent progressive dilation of ascending aorta by aortic valve replacement in patients with bicuspid aortic valve: Comparison with tricuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2003;108(suppl 1):II291–II294. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087449.03964.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hope MD, Hope TA, Crook SE, Ordovas KG, Urbania TH, Alley MT, Higgins CB. 4D flow CMR in assessment of valve-related ascending aortic disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bissell MM, Hess AT, Biasiolli L, Glaze SJ, Loudon M, Pitcher A, Davis A, Prendergast B, Markl M, Barker AJ, Neubauer S, Myerson SG. Aortic dilation in bicuspid aortic valve disease: flow pattern is a major contributor and differs with valve fusion type. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:499–507. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lehoux S, Tedgui A. Cellular mechanics and gene expression in blood vessels. J Biomech. 2003;36:631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Novaro GM, Tiong IY, Pearce GL, Grimm RA, Smedira N, Griffin BP. Features and predictors of ascending aortic dilatation in association with a congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:99–101. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang JW, Song HG, Yang DH, Baek S, Kim DH, Song JM, Kang DH, Lim TH, Song JK. Association between bicuspid aortic valve phenotype and patterns of valvular dysfunction and bicuspid aortopathy: comprehensive evaluation using MDCT and echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahle WT, Sutherland JL, Frias PA. Outcome of isolated bicuspid aortic valve in childhood. J Pediatr. 2010;157:445–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE, Jr, Eagle KA, Hermann LK, Isselbacher EM, Kazerooni EA, Kouchoukos NT, Lytle BW, Milewicz DM, Reich DL, Sen S, Shinn JA, Svensson LG, Williams DM. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College Of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation. 2010;121:e266–e369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d4739e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Douglas PS, Garcia MJ, Haines DE, Lai WW, Manning WJ, Patel AR, Picard MH, Polk DM, Ragosta M, Parker Ward R, Weiner RB. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:229–267. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aicher D, Kunihara T, Abou Issa O, Brittner B, Gräber S, Schäfers HJ. Valve configuration determines long-term results after repair of the bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2011;123:178–185. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wijesinghe N, Ye J, Rodés-Cabau J, Cheung A, Velianou JL, Natarajan MK, Dumont E, Nietlispach F, Gurvitch R, Wood DA, Tay E, Webb JG. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with bicuspid aortic valve stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:1122–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Himbert D, Pontnau F, Messika-Zeitoun D, Descoutures F, Détaint D, Cueff C, Sordi M, Laissy JP, Alkhoder S, Brochet E, Iung B, Depoix JP, Nataf P, Vahanian A. Feasibility and outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in high-risk patients with stenotic bicuspid aortic valves. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roberts WC, Janning KG, Ko JM, Filardo G, Matter GJ. Frequency of congenitally bicuspid aortic valves in patients ≥80 years of age undergoing aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis (with or without aortic regurgitation) and implications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1632–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.01.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zegdi R, Khabbaz Z, Ciobotaru V, Noghin M, Deloche A, Fabiani JN. Calcific bicuspid aortic stenosis: a questionable indication for endovascular valve implantation? Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:342. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elefteriades JA. Editorial comment: should aortas in patients with bicuspid aortic valve really be resected at an earlier stage than those in patients with tricuspid valve? Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:315–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sperling JS, Brizzio M, Zapolanski A. Bicuspid aortic valves and aortic complications. JAMA. 2011;306:2453. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1768. author reply 2453–2453; author reply 2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goland S, Czer LS, De Robertis MA, Mirocha J, Kass RM, Fontana GP, Chang W, Trento A. Risk factors associated with reoperation and mortality in 252 patients after aortic valve replacement for congenitally bicuspid aortic valve disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Forte A, Della Corte A, Grossi M, Bancone C, Provenzano R, Finicelli M, De Feo M, De Santo LS, Nappi G, Cotrufo M, Galderisi U, Cipollaro M. Early cell changes and TGFβ pathway alterations in the aortopathy associated with bicuspid aortic valve stenosis. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:97–108. doi: 10.1042/CS20120324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tamborini G, Galli CA, Maltagliati A, Andreini D, Pontone G, Quaglia C, Ballerini G, Pepi M. Comparison of feasibility and accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography versus computed tomography in patients with known ascending aortic aneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:966–969. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaplan S, Aronow WS, Ahn C, Lai H, DeLuca AJ, Weiss MB, Dilmanian H, Spielvogel D, Lansman SL, Belkin RN. Prevalence of an increased ascending thoracic aorta diameter diagnosed by two-dimensional echocardiography versus 64-multislice cardiac computed tomography. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsang JF, Lytwyn M, Farag A, Zeglinski M, Wallace K, daSilva M, Bohonis S, Walker JR, Tam JW, Strzelczyk J, Jassal DS. Multimodality imaging of aortic dimensions: comparison of transthoracic echocardiography with multidetector row computed tomography. Echocardiography. 2012;29:735–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2012.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan KL, Stinson WA, Veinot JP. Reliability of transthoracic echocardiography in the assessment of aortic valve morphology: pathological correlation in 178 patients. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brandenburg RO, Jr, Tajik AJ, Edwards WD, Reeder GS, Shub C, Seward JB. Accuracy of 2-dimensional echocardiographic diagnosis of congenitally bicuspid aortic valve: echocardiographic-anatomic correlation in 115 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1469–1473. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee SC, Ko SM, Song MG, Shin JK, Chee HK, Hwang HK. Morphological assessment of the aortic valve using coronary computed tomography angiography, cardiovascular magnetic resonance, and transthoracic echocardiography: comparison with intraoperative findings. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28(suppl 1):33–44. doi: 10.1007/s10554-012-0066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]