Abstract

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) was evaluated as a method for extracting semivolatile organic compounds (SOCs) from air sampling media; including quartz fiber filter (QFF), polyurethane foam (PUF), and a polystyrene divinyl benzene copolymer (XAD-2). Hansen solubility parameter plots were used to aid in the PLE solvent selection in order to reduce both co-extraction of polyurethane and save time in evaluating solvent compatibility during the initial steps of method development. A PLE solvent composition of 75:25% hexane:acetone was chosen for PUF. The XAD-2 copolymer was not solubilized under the PLE conditions used. The average percent PLE recoveries (and percent relative standard deviations) of 63 SOCs, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and organochlorine, amide, triazine, thiocarbamate, and phosphorothioate pesticides, were 76.7 (6.2), 79.3 (8.1), and 93.4 (2.9) % for the QFF, PUF, and XAD-2, respectively.

Keywords: Pressurized liquid extraction, Polyurethane foam, Polystyrene divinyl benzene, Quartz fiber filter, Hansen solubility parameter

Introduction

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) is an exhaustive extraction technique that uses less solvent (~100–200 mL) and time (~20 minutes) compared to traditional solvent extraction techniques such as Soxhlet extraction [1]. Extraction efficiencies reported for PLE are similar to those reported for Soxhlet and supercritical fluid extraction [2] and PLE has been shown to be effective for the extraction of semivolatile organic compounds (SOCs) from environmental matrices including: soils, particulate matter, fly ash, and sediments [3–7]. Fitzpatrik et al. previously reported important considerations for the selection of PLE parameters (e.g. cycles, temperature) [7].

For more than a decade, the global atmospheric transport of anthropogenic SOCs has been shown to cause surface contamination in remote locations [8] and atmospheric transport is a major environmental transport pathway for SOCs from source regions to remote locations [9]. Often, a quartz fiber filter (QFF) is combined with polyurethane foam (PUF) and polystyrene divinyl benzene (XAD-2) in a QFF-PUF-(XAD-2)-PUF sampling train to ensure complete collection of particulate-phase SOCs (QFF), followed by gas-phase SOCs (PUF and XAD-2) [6, 10].

Because the air sampling media used for trapping gas-phase SOCs are polymers such as PUF and XAD-2, the appropriate selection of PLE extraction solvents is essential in order to minimize matrix interferences due to co-extraction of the polymeric matrix, while simultaneously achieving adequate extraction of the SOCs. The minimization of interferences from PLE extraction cells has been reported [11]; however, the minimization of polymeric matrix interferences from air sampling media has not.

Previous research has focused on the intentional extraction of monomers/oligomers and/or polymeric additives from polymers. Lou et al. used PLE to extract monomers and oligomers from nylon-6 and poly(1,4-butyleneterephthalate), showing that the PLE extraction solvent chosen and the extraction temperature were important, but that solvent selection was “largely empirical” [12]. Vandenburg et al. proposed using Hildebrand solubility parameters to select solvents for the extraction of the polymeric additives Irganox 1010 and dioctyl phthalate from ground polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, and nylon [13].

Hildebrand solubility parameters are most effective for substances lacking any significant polar or hydrogen bonding capabilities, thus substances that primarily undergo dispersion type interactions. Hansen solubility parameters divide up the Hildebrand parameter (δ) into three components: dispersion (δD), permanent dipole-permanent dipole (δP), and hydrogen bonding (δH) forces (Equation 1) [14]. These three components take into account the similarities (or dissimilarities) of the polar and hydrogen bonding components of organic compounds to better explain the extent of interaction [14].

| (1) |

The human and environmental safety of the organic solvents used is also an important consideration in PLE solvent selection. For example, if dichloromethane, a probable human carcinogen (http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/tfacts14.pdf), is used as a PLE solvent to clean air sampling media and any residual dichloromethane remains after cleaning, it may be released during sample collection and result in human exposure [15].

To date, the use of PLE has focused on the extraction of SOCs from various solid matrices and the intentional extraction of monomers/oligomers and additives from polymers. There were two major goals in the selection of solvents for the PLE of SOCs from polymeric air sampling media. The first goal was to efficiently extract the SOCs from the media and the second goal was to avoid co-extraction of the polymeric matrix. Using Hansen solubility parameters, PLE solvents were selected which minimized co-extraction of polymeric matrix interferences, but resulted in good recoveries of 63 commonly measured SOCs. The SOCs selected for extraction and analysis were from nine chemical classes and their physical chemical properties (octanol-water partition coefficient, water solubility, and vapor pressure) spanned 7 to 10 orders of magnitude [16].

Materials and Methods

Semivolatile organic compounds (SOCs) evaluated for PLE recoveries covered several chemical classes (Table 1). A complete list of the isotopically labeled surrogates and internal standards that were used for quantitation has been previously reported [16]. The SOC standards were obtained from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency repository, Chemical Services (West Chester, PA, USA), Restek (Bellefonte, PA, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, USA). Isotopically labeled standards were obtained from CDN Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada) or Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA). The standards were stored at 4° C until use. All solvents (hexane, dichloromethane, and acetone) were from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ, USA) and were optima grade.

Table 1.

Average pressurized liquid extraction semivolatile organic compound recoveries (%relative standard deviation) from quartz fiber filter (QFF), polyurethane foam (PUF), and polystyrene divinyl benzene (XAD-2) (n=3) using the parameters and solvents listed in Table 2.

| QFF | PUF | XAD-2 | QFF | PUF | XAD-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amide Pesticides | Triazine Herbicides and Metabolites | ||||||

| Alachlor | 78.7 (5.8) | 81.7 (8.5) | 97.0 (2.1) | Atrazine desisopropyl | 81.5 (15.6) | 94.5 (7.8) | 107.7 (3.4) |

| Acetochlor | 68.3 (5.6) | 42.7 (12.6) | 87.9 (3.1) | Atrazine desethyl | 78.9 (14.4) | 93.3 (11.9) | 102.7 (1.4) |

| Metolachlor | 84.9 (7.4) | 96.1 (3.8) | 102.6 (1.9) | Atrazine | 75.1 (6.6) | 89.7 (5.2) | 90.2 (1.0) |

| Simazine | 78.9 (8.4) | 86.5 (6.4) | 102.7 (1.3) | ||||

| Organochlorines Pesticides and Metabolites | |||||||

| HCH, gamma | 76.3 (1.2) | 64.7 (1.3) | 94.5 (1.1) | Miscellaneous Pesticides | |||

| HCH, alpha | 74.9 (2.3) | 60.2 (2.2) | 92.2 (0.4) | Metribuzin | 97.3 (4.6) | 111.6 (4.8) | 90.8 (7.0) |

| HCH, beta | 83.1 (1.0) | 82.0 (1.9) | 89.9 (1.0) | Etridiazole | 79.7 (3.6) | 117.5 (7.6) | 116.5 (0.7) |

| Heptachlor | 77.8 (3.8) | 77.6 (3.6) | 111.6 (2.6) | Dacthal | 93.7 (1.7) | 105.5 (2.5) | 95.4 (3.7) |

| Heptachlor epox | 72.7 (4.6) | 67.2 (1.2) | 122.4 (1.3) | Trifluralin | 79.5 (0.8) | 80.0 (16.2) | 82.6 (4.5) |

| Endrin | 58.9 (6.7) | 107.8 (4.3) | 107.3 (2.2) | Hexachlorobenzene | 78.7 (2.4) | 81.5 (2.4) | 93.3 (1.0) |

| Endrin aldehyde | 59.7 (15.4) | 44.1 (14.7) | 92.9 (1.4) | ||||

| Chlordane, trans | 70.6 (6.2) | 49.9 (0.8) | 104.1 (1.1) | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons | |||

| Chlordane, cis | 69.7 (8.4) | 43.9 (1.0) | 82.6 (3.7) | Acenaphthene | 77.1 (4.2) | 77.3 (2.2) | 81.2 (4.4) |

| Nonachlor, trans | 69.3 (6.6) | 48.3 (1.2) | 99.3 (1.6) | Fluorene | 82.9 (2.4) | 78.7 (2.2) | 92.1 (2.2) |

| Nonachlor, cis | 57.1 (5.7) | 58.5 (1.8) | 93.9 (2.5) | Phenanthrene | 81.9 (2.5 | 83.0 (3.6) | 99.4 (2.2) |

| Chlordane, oxy | 70.6 (3.3) | 61.1 (1.3) | 118.2 (1.4) | Pyrene | 77.7 (3.2) | 83.3 (3.9) | 89.4 (2.7) |

| Aldrin | 66.5 (2.9) | 65.5 (3.3) | 99.2 (1.3) | Fluoranthene | 79.3 (3.9) | 82.5 (3.7) | 92.2 (3.0) |

| o,p'-DDT | 77.8 (6.8) | 80.6 (3.3) | 94.4 (1.5) | Chrysene + Triphenylene | 75.3 (7.1) | 86.0 (3.7) | 87.5 (1.9) |

| o,p'-DDD | 84.3 (6.1) | 87.9 (4.2) | 94.9 (1.7) | Retene | 80.5 (4.4) | 93.7 (3.2) | 114.2 (3.0) |

| o,p'-DDE | 73.2 (5.8) | 83.9 (3.6) | 104.2 (7.7) | Benzo(k)fluoranthene | 81.9 (9.8) | 84.3 (4.2) | 79.6 (2.4) |

| p,p'-DDT | 92.5 (10.7) | 87.4 (2.1) | 89.8 (0.4) | Benzo(b)fluoranthene | 83.4 (9.7) | 83.3 (4.5) | 99.2 (0.7) |

| p,p'-DDD | 84.3 (6.2) | 95.7 (5.3) | 106.3 (3.2) | Benzo(e)pyrene | 84.0 (10.1) | 84.7 (4.8) | 101.8 (3.6) |

| p,p'-DDE | 79.0 (3.7) | 87.5 (3.2) | 91.0 (1.8) | Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene | 69.9 (8.9) | 76.9 (4.0) | 93.7 (1.4) |

| Mirex | 60.4 (2.6) | 76.4 (0.4) | 86.5 (2.5) | Dibenz(a,h)anthracene | 73.3 (9.2) | 81.9 (3.4) | 89.9 (2.4) |

| Benzo(ghi)perylene | 77.4 (8.9) | 82.0 (4.3) | 88.9 (2.5) | ||||

| Organochlorine Sulfide Pesticides | |||||||

| Endosulfan I | 73.3 (9.2) | 60.4 (0.5) | 102.0 (1.1) | Polychlorinated Biphenyls | |||

| Endosulfan II | 73.9 (7.9) | 80.1 (3.0) | 97.8 (2.3) | PCB 74 | 79.5 (1.4) | 96.9 (8.1) | 93.5 (0.6) |

| PCB 101 | 82.1 (2.2) | 90.4 (7.8) | 88.7 (3.1) | ||||

| Phosphorothioate Pesticides | PCB 118 | 95.9 (5.0) | 90.7 (8.4) | 70.9 (4.6) | |||

| Methyl parathion | 73.6 (8.1) | 75.8 (2.3) | 80.7 (1.4) | PCB 153 | 73.3 (2.4) | 97.8 (8.7) | 103.9 (1.6) |

| Malathion | 69.2 (12.7) | 92.3 (5.4) | 74.0 (5.8) | PCB 138 | 78.8 (3.2) | 103.4 (8.7) | 95.2 (6.2) |

| Diazinon | 79.6 (7.1) | 81.0 (1.5) | 81.2 (2.2) | PCB 187 | 76.8 (1.7) | 88.6 (8.9) | 91.0 (1.5) |

| Parathion | 77.1 (8.4) | 75.9 (8.4) | 77.1 (3.4) | PCB 183 | 78.0 (1.5) | 82.0 (9.2) | 91.9 (1.6) |

| Ethion | 97.6 (12.4) | 113.9 (9.1) | 100.4 (8.5) | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | 73.6 (8.9) | 90.9 (2.8) | 81.8 (2.6) | ||||

| Thiocarbamate Pesticides | Avg | 76.7 (6.2) | 79.3 (8.1) | 93.4 (2.9) | |||

| EPTC | 79.9 (3.8) | 81.4 (1.7) | 83.8 (1.4) | ||||

| Pebulate | 91.2 (2.5) | 116.9 (3.5) | 88.8 (1.3) | ||||

| Triallate | 82.7 (5.5) | 123.1 (4.2) | 91.9 (2.2) | ||||

Pressurized liquid extraction solvent evaluation

The initial selection of solvents was based on Hansen solubility parameter plots for the polymeric media and solvents. Following this initial selection, two experiments were conducted to evaluate the suitability of the solvents for PLE. First, the polymeric media was cleaned by PLE with the solvents to evaluate co-extraction of the polymer. After selecting PLE solvent systems that did not significantly co-extract the polymeric media, the PLE recoveries of 63 SOCs from the sampling media were measured.

Evaluation of background interferences

In order to evaluate the potential polymeric interferences due to PLE of PUF (Tisch Environmental, Cleves, OH, USA), three 7.6 cm×7.6 cm PUF plugs were cleaned with an accelerated solvent extractor (ASE®) 300 (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in 66 ml ASE extraction cells. Sequential extractions of 100% dichloromethane, 100% acetone, 75:25% hexane:acetone, and 100% hexane were used. The ASE parameters for the four extractions were: cell temperature 100°C, static time 5 min., solvent flush 50% of cell volume, one static cycle, and a N2 purge time of 240 s. After cleaning, one PUF plug was extracted with 100% dichloromethane, the second with 100% hexane, and the third with 75:25% hexane:acetone using the same ASE parameters described above, except two static cycles were used instead of one.

Copolymers such as XAD-2 are considered non-soluble in organic solvents due to their cross linking [17]. To evaluate the potential interferences from XAD-2 (Supelco, St. Louis, MO, USA), approximately 50 g of XAD-2 were cleaned by PLE (Table 2) in a 100 ml ASE extraction cell. After cleaning, the XAD-2 was extracted with 50:50% hexane:acetone using the ASE parameters described in Table 2. The 50:50% hexane:acetone solvent system has been previously reported being used with XAD-2 and PLE (http://www1.dionex.com/en-us/webdocs/4522_AN347_V16.pdf). The PUF and XAD-2 extracts were concentrated using a Turbovap® II (Caliper Life Sciences, MA, USA) at 37 °C to approximately 600 µl and further concentrated to a final volume of approximately 300 µl using a micro N2 stream concentrator.

Table 2.

Accelerated solvent extractor (ASE®) 300 (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) parameters and solvents used to clean polystyrene divinyl benzene (XAD-2) and polyurethane foam (PUF). Quartz fiber filters (QFFs) were cleaned by baking at 350°C for 12 h. ASE® parameters and solvents used for the extraction of semivolatile organic compounds from XAD-2, PUF, and QFF are also given. Solvents included hexane (Hex) and acetone (Ace). The multiple solvents used for the extraction of the QFF, in addition to the cleaning of the XAD-2 and PUF, were sequential extractions. The ASE® parameters: Temp (extraction cell temperature), static hold time for extraction (Static), solvent flush percent of cell volume (Flush%), static cycle (Cycles), and a N2 purge time (Purge). Not applicable (NA).

| Media | Solvent | Number of Extractions |

Cycles | Temp., °C |

Static, min. |

Flush% | Purge, sec. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning | |||||||

| XAD-2 | 100% Ace | 1 | 5 | 75 | 5 | 100 | 240 |

| 25:75 Hex:Ace | 1 | 5 | 75 | 5 | 100 | 240 | |

| 50:50 Hex:Ace | 3 | 3 | 75 | 5 | 100 | 240 | |

| PUF | 100% Ace | 1 | 1 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 240 |

| 75:25 Hex:Ace | 1 | 1 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 240 | |

| 90:10 Hex:Ace | 1 | 1 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 240 | |

| QFF | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Extraction | |||||||

| XAD-2 | 50:50 Hex:Ace | 1 | 3 | 75 | 5 | 100 | 240 |

| PUF | 75:25 Hex:Ace | 1 | 2 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 240 |

| QFF | 50:50 Hex:Ace | 1 | 3 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 240 |

| 100% Hex | 1 | 3 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 240 | |

PLE recoveries

After the selection of PLE solvents was made using Hansen solubility parameter plots and the resulting polymeric interferences were evaluated, the PLE recoveries of 63 SOCs were measured in triplicate. The QFFs (Whatman, Kent, UK) were cleaned by baking at 350 °C for 12 h [6, 10] and the PUF and XAD-2 were cleaned using the ASE conditions described in Table 2. For PUF and XAD-2 cleaning, the extraction solvents were used in order of polarity (from more to less polar). After cleaning, the air sampling media was fortified with 15 µl of 10 ng/µl solutions of the target SOCs using a syringe and immediately extracted using the PLE solvents and parameters listed in Table 2. The resulting PLE extracts were fortified with 15 µl of 10 ng/µl solutions of the 24 isotopically labeled surrogates to assess SOC recoveries from the PLE step only. The extracts were concentrated to approximately 300 µl and fortified with 15 µl of 10 ng/µl solutions that contained the four isotopically labeled internal standards to track recoveries of the surrogates (i.e. recoveries from the remaining steps of the method).

Instrumental analysis

Qualitative analysis of monomeric and oligomeric interferences was conducted using gas chromatography (GC) on an Agilent 6890 gas chomatograph (Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) (Agilent 5973N, mass selective detector). A 30 m×0.25 mm inner diameter×0.25 µm film thickness, DB-5 column (J&W Scientific, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used. The GC oven temperature program was: 60 °C held for 1 min., followed by 6.0 °C/min to 300 °C and then held for 3 min, finishing with 20.0 °C/min. to 320 °C and held for 9 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in electron impact ionization mode and scanned from 35 to 500 m/z.

Quantitative analysis of SOC recoveries was conducted using the same GC/MS system in selective ion monitoring mode, using either negative chemical ionization or electron impact ionization modes, depending on which form of ionization gave the lowest instrumental detection limit. Details of the instruments, ions monitored, instrument limit of detections, and GC oven temperature program have been provided elsewhere [6, 16].

Results and Discussion

Pressurized liquid extraction solvent selection

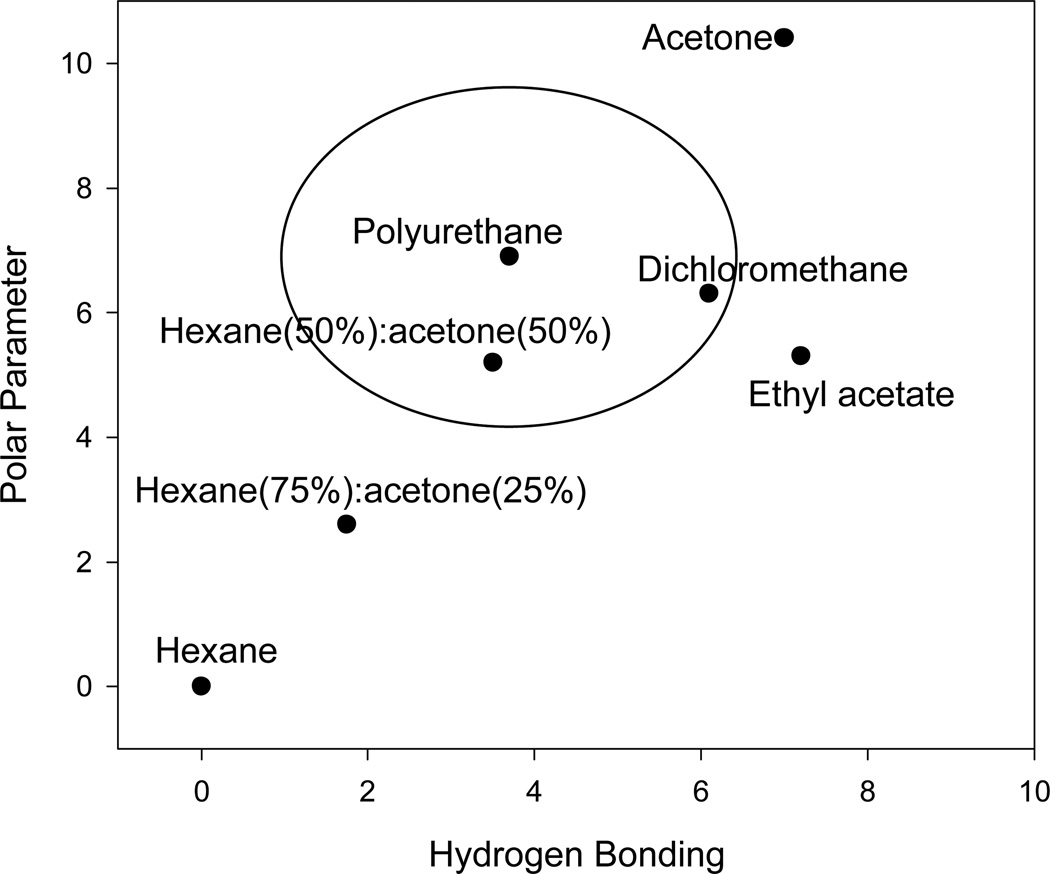

Hansen solubility parameter plots are used to graphically display the Hansen solubility parameters for various solvents and polymers. The x-axis of these plots represents the dipole-dipole and the y-axis represents the hydrogen bonding components [14]. The z-axis (dispersion) is often not displayed for organic compounds because there is usually little difference between them [14].

Hansen solubility parameters were used to identify solvents which were compatible with polyurethane. Figure 1 shows the Hansen solubility parameter plot of polyurethane with various organic solvents [14]. The solubility circle (Figure 1) represents the region where a solvent is likely to dissolve polyurethane [14]. The closer a solvent is to the center of the circle, the more likely it is to solubilize polyurethane [17]. Of the organic solvents shown in Figure 1, dichloromethane and 50:50% hexane:acetone are closest to polyurethane and hexane is the furthest. It should be noted that at higher temperatures, Hansen solubility parameters tend to decrease, while the solubilization circle tends to increase [14]. However, Hansen notes that the parameters at higher temperatures are similar to the established values at 25°C [14]. The data shown in Figure 1 is for 25 °C, which is lower than typical PLE temperatures (~100 °C).

Figure 1.

Hansen solubility parameter plot of polyurethane at 25°C [14]. Various solvents including, 100% acetone, 100% hexane, 100% ethyl acetate, 50:50% hexane: acetone, 75:25% hexane: acetone, and dichloromethane, are shown in the figure with respect to polyurethane. The circle represents the solubility circle for polyurethane (see discussion).

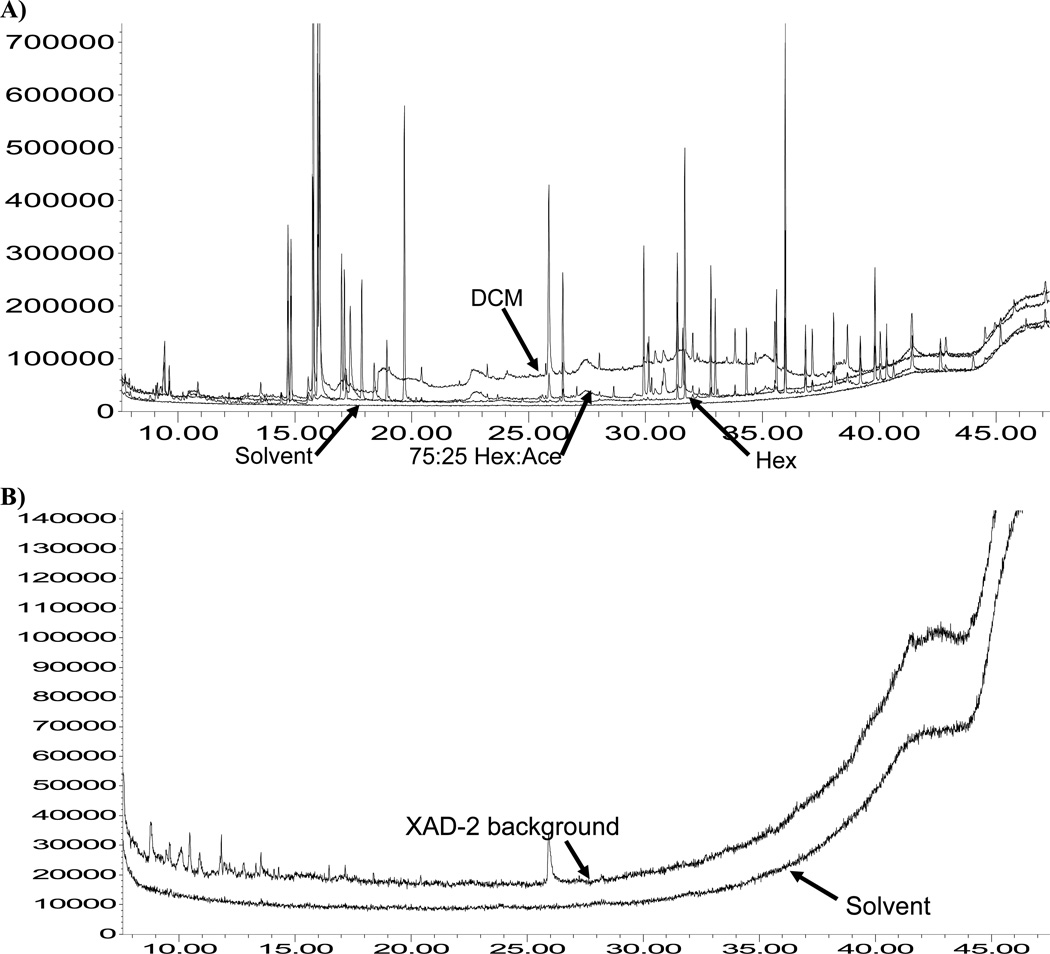

The use of PLE to extract SOCs from polymeric air sampling media with organic solvents can lead to matrix interferences. The GC/mass spectrometer chromatograms of the PLE of PUF using 100% dichloromethane, 100% hexane, and 75:25% hexane:acetone are overlaid in Figure 2A for comparison in order to evaluate the resulting matrix interferences. Figure 2A also shows a solvent injection of 100% dichloromethane. The chromatographic base-line signal was elevated when 100% dichloromethane was used as the PLE extraction solvent as compared to 75:25% hexane:acetone and 100% hexane. This result is consistent with the Hansen solubility parameter plot for polyurethane (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

(A) Total ion chromatogram of interferences due to co-extraction of monomers and oligomers from polyurethane foam (response versus time). The figure shows the effects of three pressurized liquid extraction solvents on polyurethane foam: dichloromethane (DCM), 100% hexane (Hex), and 75:25% hexane:acetone (Hex:Ace). Also shown for reference is a solvent injection of DCM. (B) Total ion chromatogram comparing polystyrene divinyl benzene (i.e. XAD-2) interferences using the pressurized liquid extraction solvent mixture of 50:50% Hex:Ace compared to a solvent injection of Hex.

A copolymer of polystyrene divinyl benzene (i.e. XAD-2), was not solubilized under the PLE conditions used. Figure 2B shows the chromatogram of a 50:50% hexane:acetone XAD-2 extract compared to a solvent injection of hexane. Because XAD-2 contains cross linking, a low signal base-line was expected [17]. Solubility parameters have not been developed for XAD-2 because it is considered non-soluble in organic solvents (B. Vogler, Supelco, St. Louis, MO, USA, personal communication). Figure 2B confirms the lack of XAD-2 solubilization during PLE. A Dionex technical report has noted the formation of naphthalene during extraction of XAD-2 at elevated temperatures, thus a PLE temperature of 75°C was chosen (Table 2) (http://www1.dionex.com/en-us/webdocs/4522_AN347_V16.pdf). For the PUF, the PLE temperature was 100°C, a typical temperature for PLE. Lower temperatures were not investigated because 100°C was found to be effective and did not damage the PUF.

Pressurized liquid extraction recovery of semivolatile organic compounds

Pressurized liquid extraction has been reported to have similar extraction efficiencies compared to Soxhlet [5], supercritical fluid extraction, and microwave assisted extraction [2]. For the PUF recovery study, the 75:25% hexane:acetone solvent system was chosen over hexane to ensure the extraction of polar, current-use pesticides. For example, atrazine recoveries were only 12% and atrazine desethyl was not detected using hexane (n=1). For more non-polar SOCs (e.g. organochlorines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), hexane was as effective as the 75:25% hexane-acetone solvent system. For QFF, PUF, and XAD-2 the average percent recoveries (and percent relative standard deviation) were 76.7 (6.2), 79.3 (8.1), and 93.4 (2.9) %, respectively (Table 1). For the PUF, the chlordane and nonachlor PLE recoveries were lower (~50%). If needed, an additional extraction cycle could be used to increase recoveries of these SOCs.

The average absolute percent SOC recovery (and percent relative standard deviation) over the entire analytical method for the QFF, PUF, and XAD-2 were 66.3 (4.8), 76.0 (5.5), and 77.1 (3.3) %, respectively. These recoveries included the solvent evaporation steps and resulted in SOC recoveries that were lower than the PLE step alone. Estimated method detection limits, calculated using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency method 8280A [18] and assuming an average air volume of 644 m3, ranged from 0.0001 to 100, 0.001 to 114, and 0.0003 to 108 pg/m3 for the QFF, PUF, and XAD-2, respectively.

Polymers (i.e. PUF and XAD-2) are effective sorbents for sampling gas-phase SOCs from the atmosphere and PLE is a rapid and effective cleaning and extraction method for the extraction of SOCs with a wide range of physical and chemical properties. Care should be taken in PLE solvent selection when extracting SOCs from polymeric sampling materials and Hansen solubility parameters can provide useful guidance to save time in evaluating solvent compatibility during the initial steps of method development.

Acknowledgement

The research described in the present study has been funded in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) under the Science to Achieve Results Graduate Fellowship Program to Toby Primbs. The U.S. EPA has not officially endorsed this publication and the views expressed herein may not reflect the views of the U.S. EPA. We also thank National Science Foundation CAREER (ATM-0239823) for funding. This work was made possible in part by The National Institute of Health (grant P30ES00210).

References

- 1.Richter BE, Jones BA, Ezzell JL, Porter NL, Avdalovic N, Pohl C. Accelerated solvent extraction: A technique for sample preparation. Anal Chem. 1996;68:1033–1039. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camel V. Recent extraction techniques for solid matrices-supercritical fluid extraction, pressurized fluid extraction and microwave-assisted extraction: Their potential and pitfalls. Analyst. 2001;126:1182–1193. doi: 10.1039/b008243k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussen A, Westbom R, Megersa N, Mathiasson L, Bjorklund E. Development of a pressurized liquid extraction and clean-up procedure for the determination of alpha-endosulfan, beta-endosulfan and endosulfan sulfate in aged contaminated Ethiopian soils. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1103:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryno M, Rantanen L, Papaioannou E, Konstandopoulos AG, Koskentalo T, Savela K. Comparison of pressurized fluid extraction, Soxhlet extraction and sonication for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban air and diesel exhaust particulate matter. J Environ Monitor. 2006;8:488–493. doi: 10.1039/b515882f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bautz H, Polzer J, Stieglitz L. Comparison of pressurised liquid extraction with Soxhlet extraction for the analysis of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans from fly ash and environmental matrices. J Chromatogr A. 1998;815:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Primbs T, Simonich S, Schmedding D, Wilson G, Jaffe D, Takami A, Kato S, Hatakeyama S, Kajii Y. Atmospheric Outflow of Anthropogenic Semivolatile Organic Compounds from East Asia in Spring 2004. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:3551–3558. doi: 10.1021/es062256w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzpatrick LJ, Zuloaga O, Etxebarria N, Dean JR. Environmental applications of pressurized fluid extraction. Rev Anal Chem. 2000;19:75–122. doi: 10.1039/b006178f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonich SL, Hites RA. Global distribution of persistent organochlorine compounds. Science. 1995;269:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.7569923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidleman TF. Atmospheric processes. Environ Sci Technol. 1988;22:361–367. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Killin RK, Simonich SL, Jaffe DA, DeForest CL, Wilson GR. Transpacific and regional atmospheric transport of anthropogenic semivolatile organic compounds to Cheeka Peak Observatory during the spring of 2002. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2004;109:D23S15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Gonzalez V, Grueiro-Noche G, Concha-Grana E, Turnes-Carou MI, Muniategui-Lorenzo S, Lopez-Mahia P, Prada-Rodriguez D. Troubleshooting with cell blanks in PLE extraction. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383:174–181. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou XW, Janssen HG, Cramers CA. Parameters affecting the accelerated solvent extraction of polymeric samples. Anal Chem. 1997;69:1598–1603. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandenburg HJ, Clifford AA, Bartle KD, Carlson RE, Caroll J, Newton ID. A simple solvent selection method for accelerated solvent extraction of additives from polymers. The Analyst. 1999;124:1707–1710. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen CM. Hansen Solubility Parameters. Boca Raton, Florida U.S.A: CRC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang JC, Holdren MW. The Presence of Dichloromethane on Cleaned XAD-2 Resin: A Potential Problem and Solutions. Environ Sci Technol. 1990;24:815–818. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usenko S, Hageman KJ, Schmedding DW, Wilson GR, Simonich SL. Trace analysis of semivolatile organic compounds in large volume samples of snow, lake water, and groundwater. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:6006–6015. doi: 10.1021/es0506511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archer WL. Industrial Solvents Handbook. New York, New York, U.S.A: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The analysis of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans by high-resolution gas chromatography/low resolution mass spectrometry (HRGC/LRMS) Washington, DC: U.S.EPA Method 8280A; 1996. [Google Scholar]