Abstract

To investigate the supplement of lost nerve cells in rats with traumatic brain injury by intravenous administration of allogenic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, this study established a Wistar rat model of traumatic brain injury by weight drop impact acceleration method and administered 3 × 106 rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via the lateral tail vein. At 14 days after cell transplantation, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into neurons and astrocytes in injured rat cerebral cortex and rat neurological function was improved significantly. These findings suggest that intravenously administered bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can promote nerve cell regeneration in injured cerebral cortex, which supplement the lost nerve cells.

Keywords: nerve regeneration, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, traumatic brain injury, intravenous administration, cell differentiation, neurologic function, cerebral cortex, rats, neural regeneration

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury is a major cause of mortality and disability worldwide (Langlois et al., 2006; Pitkänen et al., 2006; Jain, 2008). Traumatic brain injury is a heterogeneous disorder and many involved mechanisms are still unknown. Cellular death, neurodegeneration, vessel fracture, and axonal damage are several neurobiological alterations that occur during traumatic brain injury (Pitkänen et al., 2006; Jain, 2008). Current acute treatment of traumatic brain injury is limited to controlling intracranial pressure and thrombolytic surgical procedures (Harting et al., 2008). The brain has a low renewable capacity for self-repair and generation of new functional neurons in treatment of trauma, inflammation and cerebral diseases (Lu et al., 2001). Cytotherapy is one option to regenerate central nervous system that aim at replacing the functional depleted cells due to traumatic brain injury (Longhi et al., 2005; Azari et al., 2010). Lee et al. (2013) suggested combination of stem cell therapy with rehabilitation in a traumatic brain injury model to induce recovery outcomes that are similar to rehabilitation alone.

Recently, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells have become focus of intense research due to the ability of self-renewal and their potential to differentiate into various tissues (Brodhun et al., 2004; Karaoz et al., 2009). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells have capacity to cross the blood-brain barrier and migrate into injured tissues systematically. Disruption and breakage in blood-brain-barrier cause more cells to migrate into the traumatized area (Schmidt et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008). At first, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can differentiate into mesenchymal lineage cells, including neurons and non-neuronal cells in the brain (Matsushita et al., 2011). Studies have been done on the effects of stem cells on traumatic brain injury since 2001. Lu et al. (2001) administered bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells intravenously 24 hours after traumatic brain injury and sacrificed the rats 15 days later. They noticed that mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into neuronal and astrocytic phenotype cells and reversed the functional deficits in their method. In support of the above findings, others concluded that mesenchymal stem cells treatment improved brain function, stimulated the nervous system damage, and generated the loss of cell population in traumatic brain injury models (Li and Chopp, 2009). Also, these mesenchymal stem cells are capable to secret cytokines, chemokines and growth factors (Marquez-Curtis and Janowska-Wieczorek, 2013). Factors secreted by mesenchymal stem cells, such as neurotropic factors have important roles in creating favorable microenvironments for proliferation of neural cells at the injury site, so enhancing angiogenesis, synaptogenesis and neurogenesis in the damaged brain tissue (Khalili et al., 2014). Galindo et al. (2011) investigated the cytokines secreted by mesenchymal stem cells in an acute model of traumatic brain injury. They showed these factors induced the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein and modulated the in vivo inflammation in experimental traumatic brain injury. The aim of this study was to design a diffuse model of traumatic brain injury in order to investigate the role of intravenous administration of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells after experimental traumatic brain injury in rats.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and expansion of mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells were harvested from six 2-month-old male Wistar rats weighing 200–250 g as described previously (Khalili et al., 2012). The rats were anesthetized and the bone marrow plugs were extruded from bone marrow cavity. Flushing was done with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-low glucose (DMEM-LG; Gibco, Grand Island, Nebraska, USA). Pellets of bone marrow cells were separated by density gradient fractionation (400 × g for 7 minutes), then re-suspended in DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. The medium was replaced after 48 hours for removal of suspended and adherent mesenchymal stem cells, and were fed with fresh DMEM. Culture media was replaced at 3-day intervals. When the cells reached 80–90% confluence, they were passaged with 0.25% trypsin and 1 mmol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (Gibco) and expanded until 3 passages. For labeling of mesenchymal stem cells, the cells were exposed with 10 μmol/L 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) 48 hours before transplantation. BrdU was added to mesenchymal stem cell medium and replaced with nucleotide thymine in DNA of cells.

Animal model

Sixteen 3-month-old male Wistar rats, weighing 300–325 g, were kept at 25 ± 2°C and 12 hour light period. The animals were randomly divided into a traumatic brain injury (control) group and a cell transplantation (experimental) group. Traumatic brain injury was done based on diffusion model of Foda-Marmarou (Foda and Marmarou, 1994; Morales et al., 2005). The rats in the cell transplantation group were injected with 3 × 106 mesenchymal stem cells labeled with BrdU via the lateral tail vein 24 hours after induction of traumatic brain injury; and PBS was injected to the control group. Experimental protocol of this study was approved by Research and Clinical Center for Infertility, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Science Committee.

Induction of traumatic brain injury

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Traumatic brain injury was induced with weight drop impact acceleration method. A sterile metal plate was used to avoid the skull fracture. After pushing the fascia aside, the steel was located between lambda and bregma on the skull. The head was then placed in an appropriate position on a platform and a band was put under the lower jaw which allowed the head movement when the impact was created by a falling of 300 g weight. The weight was dropped from a height of 1 meter on the parietal bone.

Behavioral evaluation

Neurological severity score (NSS) was performed to evaluate the neurological function. NSS score was graded on a scale of 0 to 18 scores. Score 0 indicated normal activities, while score 18 displayed maximal deficit. NSS scale was composed of motor, sensory, balance and reflex tests. In motor test, the muscle status and ability of movement were assessed. Sensory test was composed of placing (visual and tactile) and proprioceptive tests. In balance test, score was given to procedure and time of stand on the beam. For assessment of reflex, pinna, corneal and startle reflexes were used (Chen et al., 2001). One point was given for inability of rat to perform a task. NSS test was measured on all rats pre-injury (day 0), and at 1, 7, 14 days after induction of traumatic brain injury.

istological studies

Animals were re-anesthetized with an overdose of ketamine and xylazine 14 days after traumatic brain injury induction. They were perfused intracardiacally with 200 mL of saline followed by 400 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed and stored in 4% paraformaldehyde. The parietal lobes were dissected and embedded in paraffin. A series of adjacent 6 μm coronal sections were cut, and stained with hematoxyline-eosin for histological analysis.

Immunohistochemical studies

Single and double immunohistochemical staining were used to indicate migration and differentiation of the transplanted mesenchymal stem cells. Briefly, after deparaffinization, sections were placed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in an oven at 65°C for 2 hours. Then, they were washed with PBS twice and incubated in 2 mol/L HCl at 37°C for 30 minutes. The sections were rinsed in 0.5 % Triton X-100 for 20 minutes. The sections were treated with an anti-BrdU antibody (dilution 1:100; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and antibodies for each cell marker as primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The coronal sections were washed with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or rhodamine conjugated antibody as secondary antibodies. A neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN; Millipore) for neurons (dilution 1:200) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Millipore) for astrocytes (dilution 1:200) were used as primary cell-type-specific antibodies. The combination of antibodies used in each double immunofluorescence staining was: (1) rat anti-BrdU antibody and mouse anti-NeuN antibody as primary antibodies and rhodamine-labeled anti-rat IgG antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG as secondary antibodies for BrdU-NeuN; (2) mouse anti-BrdU antibody and rabbit anti-GFAP antibody as primary antibodies and FITC-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody and rhodamine-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody as secondary antibodies for BrdU-GFAP (Yagita et al., 2001; Khalili et al., 2012). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)was added to ensure the integrity of the stained cells. The mounted slides were observed with immunofluoresence microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The differences in the data from NSS test were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and were measured with independent-sample t-test. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Verification of model establishment

Widespread hemorrhage was observed throughout the parietal surface of the brains. Hematoxylin-eosin staining indicated that blood vessels were ruptured in some slides of traumatic brain injury groups with dissecting microscope (data not shown).

Migration and differentiation of BrdU labeled bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in recipient rats

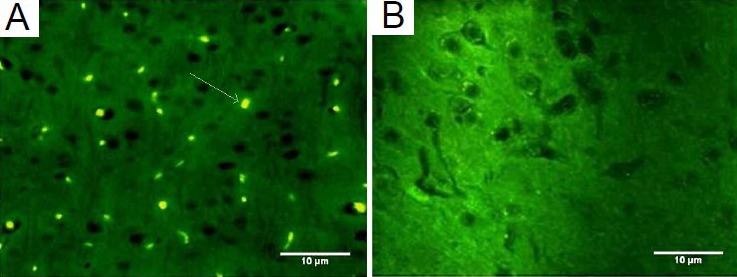

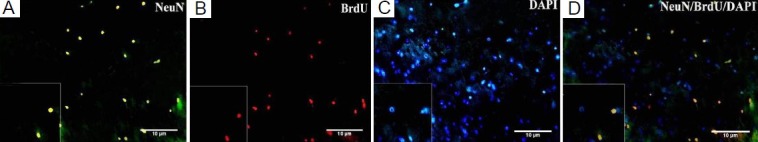

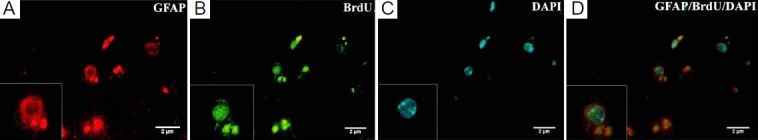

Some BrdU labeled mesenchymal stem cells migrated into the parietal lobes of injured brain in the cell transplantation group (Figure 1). In comparison, immunofluoresence microscopy of coronal sections showed no localization of BrdU-positive cells in traumatic brain injury group. In addition, double staining showed that some implanted mesenchymal stem cells expressed neuronal (neuronal nuclei, NeuN) and astrocyte (glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP) markers in the cell transplantation group (Figures 2, 3). The significant presence of NeuN and GFAP in the parietal lobes of cell transplantation group rats compared with traumatic brain injury rats indicated that some mesenchymal stem cells in the injured territory of the parietal lobe exhibited signs of differentiation towards neuron- and astrocyte-like cells.

Figure 1.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-labeled mesenchymal stem cells migrated to injured cerebral tissues following intravenous transplantation.

(A) BrdU-labeled mesenchymal stem cells (arrow) migrated into in-jured brain in the cell transplantation group via intravenous transplan-tation. (B) No BrdU-positive cells were observed in the traumatic brain injury group.

Figure 2.

Expression of neuronal marker neuronal nuclei (NeuN) in injured brain tissue after mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation.

(A) Some 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive MSCs express NeuN. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG-labeled MSCs were in green color. (B) BrdU-labeled MSCs with rhodamine-conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody as secondary antibody were in red color. (C) 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-labeled MSCs. DAPI indicated nuclei in blue color. (D) NeuN-BrdU-DAPI (× 400).

Figure 3.

Expression of astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in injured brain tissue after mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation.

(A) Some 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive MSCs express GFAP. Labeled MSCs were indicated in red color. (B) BrdU labeled MSCs with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody as secondary antibody were in green color. (C) 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-labeled MSCs. DAPI indicated nuclei in blue color. (D) GFAP-BrdU-DAPI (× 1,000).

Neurological function appraisement

NSS showed no differences between the groups of traumatic brain injury and cell transplantation at 1 and 7 days post-injury (P > 0.05), respectively. However, rat motor deficits were improved significantly in the cell transplantation group compared with traumatic brain injury group at 14 days post-injury (P = 0.01; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Neurological function pre-injury (day 0) and at 1, 7, 14 days post-traumatic brain injury (TBI) followed by cell transplantation.

Neurological severity score (NSS) was performed to evaluate the neu-rological function. NSS was graded on a scale of 0 to 18 score. Score 0 indicates normal activities, while score 18 displays maximal deficit. Values are expressed as mean ± SD with eight rats at each time point in each group. *P < 0.05, vs. TBI group.

Discussion

In this study, mesenchymal stem cells intravenously administered were shown to migrate into injured cerebral tissue at 14 days after diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. This type of traumatic brain injury model in conjunction with stem cell therapy has been rarely reported. The intravenously administered mesenchymal stem cells expressed neuronal marker NeuN and astrocyte marker GFAP and promoted functional recovery at the end of the second week.

On the contrary, the control group showed no improvement in animal behavior after diffuse traumatic brain injury. Intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells promoted neuronal regeneration following experimental diffuse traumatic brain injury. It seems that intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells after experimental traumatic brain injury promoted neuronal proliferation and differentiation in neurogenic zones and improved motor and sensory recovery (Opydo-Chanek, 2007; Harting et al., 2009; Joers and Emborg, 2010). As in a previous study (Khalili et al., 2012), we took advantage of the intravenous transplantation as being minimally invasive procedure. Mahmood et al. (2001) used intravenous transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of local traumatic brain injury and found that this method is better than other methods. This approach has beneficial effects than carotid or direct tissue injection and is also appropriate for long-term treatment (Chopp and Li, 2002).

The cell homing is one of the controversial topics in intravenous route. There is a possibility of the cell pooling in the other organs, such as lungs, entrapment in the peripheral organs and reducing cell homing, which require higher cell numbers (Reitz et al., 2012). Lu et al. (2001) injected BrdU-labeled mesenchymal stem cells into rat tail vein, and traced these cells in different organ tissues. They observed mesenchymal stem cells homing into other organs in addition to injured cerebral tissue without causing harms to these organs. The exact number of mesenchymal stem cells that are necessary for repair of the functional deficits after injury is one of the important issue that should be resolved. In this study, 3 × 106 mesenchymal stem cells were injected at an appropriate dose for trauma treatment. Lu et al. (2003) compared two different doses in intravenous infusion at 24 hours after brain injury. They noticed significant functional recovery in animals that received 3 × 106 mesenchymal stem cells than other group receiving 1 million cells. Similarly, in another study reported by Mahmood et al. (2005), two doses (2 and 4 × 106) of cells were intravenously transplanted in traumatic brain injury program. Three months later, the recipient animals that received 4 × 106 mesenchymal stem cells had better recovery than those receiving 2 × 106 mesenchymal stem cells. These studies suggest that the number of mesenchymal stem cells is a determining factor for gaining optimal results.

Our finding showed that at 24 hours after traumatic brain injury, intravenously injected mesenchymal stem cells improved neurological function, which is similar to other investigations (Lu et al., 2001; Mahmood et al., 2001). Future research in this field should ensure that the cells remain a long-term period in the target area. Later, Bonilla et al. (2009) indicated that administration of 1 × 107 mesenchymal stem cells in the injured brain caused a clear recovery 2 months after traumatic brain injury. Therefore, it is necessary to know the best route and time of mesenchymal stem cell administration in order to obtain the favorable results for cell therapy after traumatic brain injury in rats. However, the mechanism by which the injected mesenchymal stem cells help to repair injured brain after stroke or traumatic brain injury. Only a small number of intravenously injected cells can reach the damaged cerebral tissue. Therefore, just a small proportion of cells arrive at the damaged area and form complex connection for functional recovery. More likely, the injected mesenchymal stem cells stimulate the cerebral area to activate endogenous restorative and regenerative mechanisms (Chopp and Li, 2002). They behave as small factories capable of secreting cytokines and neurotrophic factors, such as nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and fibroblast growth factors (Parr et al., 2007). There is some evidence that stem cells have intrinsic capacity to detect pathological areas within the brain, for example, vascular endothelial growth factor that is released in many neurological disorders and migrates towards damaged area (Collins, 2013). Mesenchymal stem cell supernatant is more robust than direct use of vascular endothelial growth factor which suggests that mesenchymal stem cells are an available source of angiogenic factors (Hamano et al., 1999). Others tested the effects of mesenchymal stem cells on the induction of angiogenesis and showed that mesenchymal stem cells could induce the formation of new blood vessels, suggesting an improvement in functional recovery (Khalili et al., 2012). Mesenchymal stem cells integrated into injured tissue, forming cell-cell communications, interacted with the extracellular matrix, differentiated into neurons, and may be associated with brain plasticity and reduction of apoptosis. Thus, mesenchymal stem cell transplantation amplifies treatment and contributes to the restoration and functional improvement after diffuse traumatic brain injury (Vaquero and Zurita, 2011).

Intravenous transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells decreased neurological deficits and provided therapeutic benefits in an animal model. Meesnchymal stem cells seem as an excellent source of reserving cells for acute and diffuse traumatic brain injury. Additional studies are necessary to explore the safety and efficacy of these cells during long-term therapy.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Mojde Saboor and Fatemeh Mousavi (Research and Clinical Center for Infertility ShahidSadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran) for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Funding: This study was supported by research center from Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran.

Copyedited by Xie MH, Wang MQ, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- 1.Azari MF, Mathias L, Ozturk E, Cram DS, Boyd RL, Petratos S. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of CNS injury. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:316–323. doi: 10.2174/157015910793358204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonilla C, Zurita M, Otero L, Aguayo C, Vaquero J. Delayed intralesional transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells increases endogenous neurogenesis and promotes functional recovery after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2009;23:760–769. doi: 10.1080/02699050903133970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodhun M, Bauer R, Patt S. Potential stem cell therapy and application in neurotrauma. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2004;56:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang Z, Lu D, Lu M, Chopp M. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2001;32:1005–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopp M, Li Y. Treatment of neural injury with marrow stromal cells. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:92–100. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins TR. Neural stem cells reach gliomas intranasally. Neurol Today. 2013;13:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foda MA, Marmarou A. A new model of diffuse brain injury in rats Part II: Morphological characterization. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:301–313. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.2.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galindo LT, Filippo TR, Semedo P, Ariza CB, Moreira CM, Camara NO, Porcionatto MA. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy modulates the inflammatory response in experimental traumatic brain injury. Neurol Res Int 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/564089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamano K, Li TS, Kobayashi T, Kobayashi S, Matsuzaki M, Esato K. Angiogenesis induced by the implantation of self-bone marrow cells: a new material for therapeutic angiogenesis. Cell Transplant. 2000;9:439–443. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harting MT, Baumgartner JE, Worth LL, Ewing-Cobbs L, Gee AP, Day MC, Cox CS., Jr Cell therapies for traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E18. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/3-4/E17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harting MT, Jimenez F, Xue H, Fischer UM, Baumgartner J, Dash PK, Cox CS., Jr Intravenous mesenchymal stem cell therapy for traumatic brain injury: Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:1189–1197. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain KK. Neuroprotection in traumatic brain injury. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:1082–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joers VL, Emborg ME. Preclinical assessment of stem cell therapies for neurological diseases. ILAR J. 2009;51:24–41. doi: 10.1093/ilar.51.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karaoz E, Aksoy A, Ayhan S, Sariboyaci AE, Kaymaz F, Kasap M. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from rat bone marrow: ultrastructural properties, differentiation potential and immunophenotypic markers. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;132:533–546. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalili MA, Anvari M, Hekmati-Moghadam SH, Sadeghian-Nodoushan F, Fesahat F, Miresmaeili SM. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalili MA, Sadeghian-Nodoushan F, Fesahat F, Mir-Esmaeili SM, Anvari M, Hekmati-Moghadam SH. Mesenchymal stem cells improved the ultrastructural morphology of cerebral tissues after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Exp Neurobiol. 2014;23:77–85. doi: 10.5607/en.2014.23.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375–378. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee DH, Lee JY, Oh BM, Phi JH, Kim SK, Bang MS, Kim SU, Wang KC. Functional recovery after injury of motor cortex in rats: effects of rehabilitation and stem cell transplantation in a traumatic brain injury model of cortical resection. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1969-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Chopp M. Marrow stromal cell transplantation in stroke and traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Lett. 2009;456:120–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu K, Chi L, Guo L, Liu X, Luo C, Zhang S, He G. The interactions between brain microvascular endothelial cells and mesenchymal stem cells under hypoxic conditions. Microvasc Res. 2008;75:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longhi L, Zanier ER, Royo N, Stocchetti N, McIntosh TK. Stem cell transplantation as a therapeutic strategy for traumatic brain injury. Transpl Immunol. 2005;15:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu D, Mahmood A, Wang L, Li Y, Lu M, Chopp M. Adult bone marrow stromal cells administered intravenously to rats after traumatic brain injury migrate into brain and improve neurological outcome. Neuroreport. 2001;12:559–563. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu M, Chen J, Lu D, Yi L, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Global test statistics for treatment effect of stroke and traumatic brain injury in rats with administration of bone marrow stromal cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;128:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahmood A, Lu D, Wang L, Li Y, Lu M, Chopp M. Treatment of traumatic brain injury in female rats with intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1196–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmood A, Lu D, Qu C, Goussev A, Chopp M. Human marrow stromal cell treatment provides long-lasting benefit after traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1026–1031. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000181369.76323.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquez-curtis LA, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Enhancing the migration ability of mesenchymal stromal cells by targeting the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Biomed Res Int 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/561098. Article ID 561098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsushita T, Kibayashi T, Katayama T, Yamashita Y, Suzuki S, Kawamata J, Honmou O, Minami M, Shimohama S. Mesenchymal stem cells transmigrate across brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayers through transiently formed inter-endothelial gaps. Neurosci Lett. 2011;502:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morales DM, Marklund N, Lebold D, Thompson HJ, Pitkanen A, Maxwell WL, Longhi L, Laurer H, Maegele M, Neugebauer E, Graham DI, Stocchetti N, McIntosh TK. Experimental models of traumatic brain injury: do we really need to build a better mousetrap? Neuroscience. 2005;136:971–989. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opydo-Chanek M. Bone marrow stromal cells in traumatic brain injury (TBI) therapy: true perspective or false hope? Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2007;67:187–195. doi: 10.55782/ane-2007-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parr AM, Tator CH, Keating A. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the repair of central nervous system injury. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:609–619. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitkänen A, Longhi L, Marklund N, Morales DM, Mcintosh TK. Neurodegeneration and neuroprotective strategies after traumatic brain injury. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2006;2:409–418. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reitz M, Demestre M, Sedlacik J, Meissner H, Fiehler J, Kim SU, Westphal M, Schmidt NO. Intranasal delivery of neural stem/progenitor cells: a noninvasive passage to target intracerebral glioma. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:866–873. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt A, Ladage D, Steingen C, Brixius K, Schinköthe T, Klinz FJ, Schwinger RH, Mehlhorn U, Bloch W. Mesenchymal stem cells transmigrate over the endothelial barrier. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaquero J, Zurita M. Functional recovery after severe CNS trauma: current perspectives for cell therapy with bone marrow stromal cells. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yagita Y, Kitagawa K, Ohtsuki T, Takasawa KI, Miyata T, Okano H, Hori M, Matsumoto M. Neurogenesis by progenitor cells in the ischemic adult rat hippocampus. Stroke. 2001;32:1890–1896. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.8.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]