Abstract

The present study aimed to compare in vivo measurements of skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity made using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) with the current gold standard, namely in situ measurements of high-resolution respirometry performed in permeabilized muscle fibres prepared from muscle biopsies. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity was determined in 21 healthy adults in vivo using NIRS to measure the recovery kinetics of muscle oxygen consumption following a ∼15 s isometric contraction of the vastus lateralis muscle. Maximal ADP-stimulated (State 3) respiration was measured in permeabilized muscle fibres using high-resolution respirometry with sequential titrations of saturating concentrations of metabolic substrates. Overall, the in vivo and in situ measurements were strongly correlated (Pearson's r = 0.61–0.74, all P < 0.01). Bland–Altman plots also showed good agreement with no indication of bias. The results indicate that in vivo NIRS corresponds well with the current gold standard, in situ high-resolution respirometry, for assessing mitochondrial respiratory capacity.

Key points

In vivo skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity was determined from the post-exercise recovery kinetics of muscle oxygen consumption (mVO2) measured using near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in humans.

NIRS recovery rates were compared with the in situ gold standard of high-resolution respirometry measured in permeabilized muscle fibre bundles prepared from muscle biopsies taken from the same participants.

NIRS-measured recovery kinetics of mVO2 were well correlated with maximal ADP-stimulated mitochondrial respiration in permeabilized fibre bundles.

NIRS provides a cost-effective, non-invasive means of assessing in vivo mitochondrial respiratory capacity.

Introduction

Mitochondria, because of their bioenergetic role in energy provision through oxidative phosphorylation, play a crucial role in cellular function. Alterations in mitochondrial structure and/or function can lead to impairments in oxidative phosphorylation (i.e. mitochondrial respiratory capacity), which in turn can reduce energy production, increase reactive oxygen species production, alter cellular redox state, deregulate calcium homeostasis and trigger mitoptosis/apoptosis. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity can be perturbed by genetic alterations (i.e. nuclear and/or mitochondrial DNA mutations/deletions) and environmental factors (Wallace, 2013). The mitochondria's capacity for oxidative phosphorylation has been linked to whole body aerobic capacity and exercise performance (Holloszy, 1967; Larson-Meyer 2001; Seifert et al. 2012). Moreover, reduced mitochondrial respiratory capacity has also been implicated as an important factor in pathologies associated with ageing (Conley et al. 2000b; Coen et al. 2013; Layec et al. 2013) and neuromuscular diseases (Vorgerd et al. 2000; Johri & Beal, 2012; Breuer et al. 2013), especially in tissues where the demand for ATP synthesis is large or can change rapidly.

The mitochondria's capacity for oxidative phosphorylation is typically measured indirectly as mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Several in vitro, in situ and in vivo techniques are now available for researchers and clinicians to examine aspects of mitochondrial function. In vitro and in situ techniques are generally used in either cultured cells, isolated mitochondria or permeabilized cells and can measure mitochondrial functional respiratory capacity indirectly (ATP production by bioluminescence; Lanza & Nair, 2009) or more commonly via direct phosphorescence or amperopmetric-based measurements of oxygen consumption rate (Gnaiger, 2009; Brand & Nicholls, 2011; Perry et al. 2013). These in vitro and in situ techniques offer the ability to probe specific complexes of the electron transport system (ETS), providing important information for understanding the mechanisms of altered mitochondrial function. However, a potential limitation of these approaches lies in their translational significance, as many experimental protocols subject these tissues to non-physiological conditions.

In contrast, in vivo methodologies allow for measurements within living organisms with intact circulatory and regulatory systems. Phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) has been extensively used to assess kinetic changes in phosphocreatine during exercise and the recovery after cessation of exercise (Chance et al. 2006; Layec et al. 2011). Despite the fact that 31P-MRS has been validated under a number of experimental conditions (McCully et al. 1993; Larson-Meyer et al. 2001; Lanza et al. 2011), its widespread use is limited due to the low availability of multinuclear MR scanners and the high cost. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) utilizes the oxygen-dependent absorption of NIR light by haemoglobin/myoglobin to monitor tissue oxygenation (Jobsis, 1977). NIRS has been used to monitor changes in skeletal muscle oxygenation (Hampson & Piantadosi, 1988; Seiyama et al. 1988), blood flow (Deblasi et al. 1994; Boushel et al. 2000; Van Beekvelt et al. 2001a) and oxygen consumption (Hamaoka et al. 1996; Malagoni et al. 2010). NIRS has also been used to investigate muscle oxidative metabolism by examining the kinetics of muscle deoxygenation during constant load (Belardinelli et al. 1997; Grassi et al. 2003) and incremental (Boone et al. 2009; Salvadego et al. 2013) exercise, although these approaches provide information about the balance between oxygen delivery and extraction rather than solely oxygen consumption per se. Recent advances in NIRS have resulted in the development of a novel in vivo technique for assessing the recovery kinetics of muscle oxygen consumption (mVO2), an index of mitochondrial respiratory capacity (Nagasawa et al. 2003; Motobe et al. 2004; Ryan et al. 2012, 2013c). In the present study, we compared in vivo skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity in humans measured with NIRS with in situ measurements of mitochondrial respiratory capacity measured by high-resolution respirometry in permeabilized skeletal muscle fibre bundles prepared from muscle biopsies of the same individuals. We hypothesized that maximal skeletal muscle oxygen utilization determined from the recovery kinetics of mVO2 measured in vivo by NIRS would be correlated with mitochondrial respiratory capacity measured in situ by high-resolution respirometry.

Methods

Participants

Healthy male (n = 12) and female (n = 9) adult participants (age = 25.6 ± 1.8 years (range 18–44 years), height = 1.73 ± 0.01 m, weight = 72.1 ± 3.3 kg, body mass index = 23.9 ± 0.8(kg/m2), adipose tissue thickness = 9.2 ± 0.9 mm) were recruited from the local community. All participants completed a health history questionnaire to ensure there was no presence of chronic disease. All participants were non-smokers and none was taking any medications known to alter metabolism. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board for human subjects at East Carolina University and were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Study design

All participants underwent two testing sessions. NIRS testing was performed during the first testing session after obtaining consent and a health history via a questionnaire. Participants returned to the laboratory within 3–7 days in the morning after an overnight fast and rested for 20 min. Participants were instructed to abstain from strenuous physical activity for at least 24 h prior to each testing session. On the day of the muscle biopsy experiment, participants reported to the laboratory following an overnight fast (∼10 h). Muscle biopsies were obtained from the lateral aspect of the vastus lateralis by percutaneous needle biopsy under local anaesthesia (1% lidocaine).

NIRS measurements

The NIRS testing protocol was similar to that described in previous studies (Brizendine et al. 2013; Ryan et al. 2013c). NIRS data were acquired using a frequency-domain device (OxiplexTS, ISS, Champaign, IL, USA), equipped with two independent data acquisition channels, each equipped with eight IR diode lasers (four emitting at 691 nm and four at 830 nm) and a detector. In the current study, we employed a single channel (i.e. probe) setup with emitter–detector distances of 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 and 3.5 cm. The absorption (μa) and reduced scattering (μs′) coefficients were calculated from the amplitude and phase of the intensity-modulated light via the manufacturer's software. The absolute values of oxygenated haemoglobin [O2Hb] and deoxygenated haemoglobin [HHb] were calculated in micromoles using the Beer–Lambert Law and assuming a water content of 70%. Data were collected at 4 Hz.

The NIRS probe was positioned longitudinally on the belly of the vastus lateralis muscle of the right leg ∼10 cm above the patella. The probe was secured with double-sided adhesive tape and Velcro straps around the thigh. The NIRS device was calibrated prior to each test using a phantom with known optical properties after a warm-up period of at least 30 min. A blood pressure cuff (Hokanson SC-10D or SC-10L, D.E. Hokanson, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA) was placed proximal to the NIRS probe as high as anatomically possible on the thigh. The blood pressure cuff was controlled with a rapid-inflation system (Hokanson E20, D.E. Hokanson) set to a pressure of >250 mmHg and powered with a 15-gallon air compressor (Model D55168, Dewalt, Baltimore, MD, USA). Skin and adipose tissue thickness was measured at the site of the NIRS probe using skinfold calipers (Lange, Beta Technology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

The NIRS experimental protocol consisted of two measurements of resting muscle oxygen consumption (mVO2) after inflation of the blood pressure cuff for 30 s. mVO2 was calculated as the rate of change (i.e. slope) of the HHb signal during the arterial occlusion via simple linear regression. Following the resting measurements, participants performed a short duration (∼10–20 s) isometric contraction of the quadriceps muscle group to increase mVO2. Upon relaxation, the recovery kinetics of mVO2 were measured using a series of transient arterial occlusions with the following timing: 5 s on/5 s off for occlusions 1–5, 7 s on/7 s off for occlusions 6–10, and 10 s on/10 s off for occlusions 11–20. Post-exercise mVO2 was calculated for each occlusion using simple linear regression with the start and end of each occlusion marked to allow for standardized (i.e. no user bias) calculations of mVO2. Post-exercise mVO2 measurements were fit to a monoexponential function as follows:

| (1) |

where y is the relative mVO2 during the arterial occlusion, end is the mVO2 immediately following exercise, delta is the change in mVO2 from rest to end-exercise, k is the fitting rate constant and t is time. According to this first-order metabolic model, the recovery kinetics follow a monoexponential function which is independent of exercise intensity (Crow & Kushmerick, 1982; Mahler, 1985; Meyer, 1988; Paganini et al. 1997; Walter et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 2013a). The rate constant was used as an index of mitochondrial respiratory capacity, as previously described (Ryan et al. 2013c). The exercise and occlusion procedure was performed twice and the results were averaged. An ischaemic calibration was performed at the end of each test, as previously described (Ryan et al. 2013a). NIRS data were analysed using custom-written routines in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

Preparation of permeabilized muscle fibres

Approximately 100–150 mg of skeletal muscle was obtained from the vastus lateralis muscle by percutaneous muscle biopsy under local anaesthetic (1% lidocane). A portion of each muscle sample was immediately placed in ice-cold buffer X (50 mm K-MES, 7.23 mm K2EGTA, 2.77 mm CaK2EGTA, 20 mm imidazole, 20 mm taurine, 5.7 mm ATP, 14.3 mm phosphocreatine and 6.56 mm MgCl2.6H2O, pH 7.1) for preparation of permeabilized fibre bundles (PmFBs), as previously described (Perry et al. 2011). Fibre bundles were separated along their longitudinal axis using needle-tipped forceps under magnification (MX6 Stereoscope, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), permeabilized with saponin (30 μg ml−1) for 30 min at 4°C, and subsequently washed in cold buffer Z (105 mm K-MES, 30 mm KCl, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm K2HPO4, 5 mm MgCl2.6H2O, 0.5 mg ml−1 BSA, pH 7.4) for ∼20 min until analysis. At the conclusion of each experiment, PmFBs were washed in double-distilled H2O to remove salts, and freeze-dried (Labconco, Kansas, MO, USA), and weighed. Typical fibre bundle sizes were 0.2–0.6 mg dry weight.

Mitochondrial respiration

High-resolution O2 consumption measurements were conducted in 2 ml of buffer Z containing 20 mm creatine and 25 μm blebbistatin to inhibit contraction (Perry et al. 2011) using the OROBOROS Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). Polarographic O2 measurements were acquired at 2 s intervals with the steady state rate of respiration calculated from a minimum of 40 data points and expressed as pmol s−1 per mg dry weight. All respiration measurements were conducted at 37°C and a working range [O2] of ∼350–180 μm. Two respiration protocols were used, each run in duplicate, as follows: Protocol 1 comprised 10 mm glutamate + 2 mm malate (complex I substrates), followed by sequential additions of 5 mm ADP, 10 mm succinate (complex II substrate), 1 μm rotenone (complex I inhibitor) and 1 μm cytochrome c to test for mitochondrial membrane integrity; Protocol 2 comprised 2–25 μm palmitoyl-l-carnitine (β-oxidation) + 2 mm malate, followed by sequential additions of 5 mm ADP, 5 mm glutamate, 10 mm succinate, 1 μm rotenone and 1 μm cytochrome c.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Comparisons between methods were performed using a Pearson correlation coefficient and one-tailed t test for significance. The level of agreement between NIRS and respirometry was assessed using Bland–Altman 95% limits of agreement analyses, which provide an indication of the level of agreement (i.e. how close are the values to zero), as well as whether there is any relationship between measurement error and the true value (i.e. more error with larger values). Because the two techniques have different units of measurement, Bland–Altman analyses were performed with computed standardized Z scores for each measurement. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

NIRS measured mitochondrial capacity

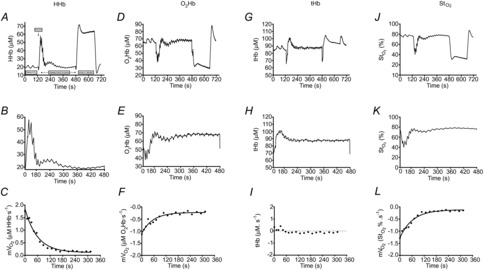

Resting mVO2 for all participants averaged 0.058 ± 0.011 μm HHb s−1. Previous studies using continuous wave NIRS devices have reported that adipose tissue thickness can influence NIRS measurements (Van Beekvelt et al. 2001b; Ryan et al. 2012). Using frequency-domain NIRS measurements, we found no relationship between resting mVO2 and adipose tissue thickness (R2 = 0.06), suggesting that a ‘physiological’ calibration may not be necessary with frequency-domain NIRS devices. A representative NIRS test is shown in Fig. 1. The rate constant for the recovery of mVO2 averaged 0.031 ± 0.002 s−1 (Time Constant = 35.3 ± 2.3 s) for all participants, with a range of 0.016 s−1 (Time Constant = 62.5 s) to 0.051 s−1 (Time Constant = 19.6 s). These values are in close agreement with previous studies (Ryan et al. 2012; Brizendine et al. 2013; Erickson et al. 2013). The initial end-exercise mVO2 was 0.47 ± 0.12 μm HHb s−1, which is equivalent to a 14.8 ± 4.8-fold increase from resting mVO2.

Figure 1.

Representative NIRS data

NIRS deoxygenated haemoglobin/myoglobin (HHb) signal collected from the vastus lateralis muscle. A, the test protocol consisted of two measurements of resting mVO2, by way of arterial occlusion, post-exercise recovery kinetics of mVO2 and an ischaemic calibration. B, post-exercise recovery kinetics of mVO2 was measured using transient repeated arterial occlusions. C, post-exercise measurements of mVO2 were fit to a monoexponential curve to characterize the rate constant (index of mitochondrial respiratory capacity). Representative NIRS data are also shown for oxygenated haemoglobin/myoglobin (O2Hb), total haemoglobin (tHb) and tissue saturation (StO2) signals for the entire test protocol (D, G and J, respectively), the post-exercise recovery kinetics (E, H and K, respectively) and post-exercise mVO2 measurements (F, I and L, respectively).

Mitochondrial respiration in PmFBs

Mitochondrial respiration from PmFBs from muscle tissue acquired via a percutaneous biopsy exhibit the expected patterns in response to the substrate–inhibitor titration protocols. Specifically, State 2 respiration in the presence of carbohydrate-based complex I substrates (glutamate/malate) was 28.6 ± 1.3 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight and fatty acid-based substrates (palmitoyl-l-carnitine/malate) was 25.8 ± 1.3 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight. ADP-stimulated respiration (State 3) was assessed after the addition of saturating concentrations of ADP. Complex I supported State 3 respiration increased to 148.8 ± 4.6 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight (glutamate+malate+ADP) and 167 ± 6.9 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight (palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+ADP+glutamate). Convergent electron flow through both complex I and II was then assessed by the subsequent addition of succinate, generating a further increase in respiration to 219.62 ± 8.7 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight (glutamate+malate+ADP+succinate) and 244.0 ± 9.0 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight (palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+ADP+glutamate+succinate). Complex II supported State 3 respiration (assessed by the addition of the complex I inhibitor rotenone) was 121.5 ± 5.7 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight (glutamate+malate+ADP+succinate+rotenone) and 129.7 ± 7.8 pmol s−1 per mg dry weight (palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+ADP+glutamate+succinate+rotenone). The respiratory control ratio (State 3/State 2) was 8.7 ± 0.5 (Protocol 1) and 6.9 ± 0.6 (Protocol 2), indicating well-coupled mitochondria in the fibre preparations. Addition of cytochrome c at the end of each protocol did not elicit a significant increase in respiration (all tests less than 5%), indicating good integrity of the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Relationship between mitochondrial respiratory capacity measured in vivo and in situ

NIRS rate constants were well correlated with State 3 respiration with complex I substrates (r = 0.61 and 0.64 for Protocol 1 and 2, respectively, P < 0.01), complex I+II (r = 0.68 and 0.69 for Protocol 1 and 2, respectively, P < 0.01) and complex II with the inhibition of complex I by rotenone (r = 0.69 and 0.74 for Protocol 1 and 2, respectively, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Bland–Altman plots (Fig. 3) for standardized Z scores demonstrate the level of agreement with no bias. Statistical values regarding the Bland–Altman limits of agreement analysis can be found in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Comparison of in vivo (NIRS) and in situ (high-resolution respirometry) indices of skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity

Correlations between NIRS rate constants for the post-exercise recovery of mVO2 and maximal ADP-stimulated (State 3) respiration in permeabilized muscle fibres from the vastus lateralis muscle in healthy adults in the presence of substrates providing electron flow through Complex I+II (A, glutamate+malate+succinate; D, palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+glutamate+succinate), Complex I only (B, glutamate+malate; E, palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+glutamate) and Complex II only (C, glutamate+malate+succinate+rotenone; F, palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+glutamate+succinate+rotenone); n = 21 for A–C; n = 17 for D–F. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Level of agreement between in vivo (NIRS) and in situ (high-resolution respirometry) indices of skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity

Bland–Altman plots (difference vs. average) of in vivo and in situ measurements of skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity from the vastus lateralis muscle in healthy adults. Because the two measurement methods have differing units of value, we calculated standardized Z-scores for the study sample. Complex I+II (A, glutamate+malate+succinate; D, palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+glutamate+succinate), Complex I only (B, glutamate+malate; E, palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+glutamate) and Complex II only (C, glutamate+malate+succinate+rotenone; F, palmitoyl-l-carnitine+malate+glutamate+succinate+rotenone); n = 21 for A–C; n = 17 for D–F. Dashed lines represent the 95% limits of agreement (mean ± 1.96SD), for which 95% of measurements are expected to lie between.

Table 1.

Results from Bland–Altman limits of agreement analysis

| 95% Limits of agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol | Mean difference (SE) | Lower limit (95% CI) | Upper limit (95% CI) |

| G+M+D | 1.90 × 10−8 (0.27) | −2.45 (−1.46 to −3.45) | 2.45 (1.46 to 3.45) |

| G+M+D+S | 5.71 × 10−8 (0.17) | −1.56 (−0.93 to −2.19) | 1.56 (0.93 to 2.19) |

| G+M+D+S+ROT | 4.76 × 10−8 (0.17) | −1.53 (−0.91 to −2.15) | 1.53 (0.91 to 2.15) |

| PC+M+D+G | 4.70 × 10−8 (0.22) | −1.80 (−0.98 to −2.62) | 1.80 (0.98 to 2.62) |

| PC+M+D+G+S | −1.76 × 10−8 (0.18) | −1.53 (−0.83 to −2.23) | 1.53 (0.83 to 2.23) |

| PC+M+D+G+S+ROT | 3.82 × 10−8 (0.17) | −1.41 (−0.77 to −2.05) | 1.41 (0.77 to 2.05) |

Limits of Agreement analysis was performed for the comparison of NIRS with high-resolution respirometry. The mean difference (and corresponding standard error) between NIRS and maximal state 3 respiration was calculated from standardized Z-scores. Upper and lower limits (95%) were calculated based on the mean ± 1.96SD, as well as, the 95% confidence interval for each limit of agreement (using the appropriate value in the t distribution for α = 0.05). G, glutamate; M, malate; D, ADP; S, succinate; PC, palmitoyl-l-carnitine; ROT, rotenone; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

This study provides clear evidence, for the first time, that skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity measured in vivo by frequency-domain NIRS correlates well with mitochondrial respiratory capacity measured by high-resolution respirometry in permeabilized fibre bundles from human muscle samples. With the continued growth in understanding of the role of mitochondria in health and disease, it is becoming increasingly important to develop and validate cost-effective, accurate and clinically useful techniques to study mitochondrial function. The NIRS technique described here fills a unique void in this area. NIRS is a completely non-invasive approach well suited for use in both healthy and clinical human populations, and is far more affordable than MRS (Ferrari et al. 2011). Moreover, NIRS has now been validated under a number of different experimental conditions, providing both indirect (Brizendine et al. 2013; Erickson et al. 2013; Ryan et al. 2013b) and direct (Nagasawa et al. 2003; Ryan et al. 2013c) evidence supporting both its validity and its accuracy.

In situ (PmFBs) and in vitro (isolated mitochondria) measurements in tissue samples have been used extensively to investigate mitochondrial physiology and pathophysiology (Brand & Nicholls, 2011; Perry et al. 2013), due in part to the ability to perform experiments under tightly controlled conditions. While such approaches can provide important mechanistic insight, they are limited by the inability to completely recapitulate the constant state of fluxes that constitute the balance of bioenergetic demand and supply of the ETS in vivo. Thus, in situ and in vitro approaches can only provide insight as to what the potential physiology or pathophysiology may be in vivo. The NIRS approach provides a cost-effective non-invasive reliable means of assessing at least one characteristic of mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle in vivo, maximal respiratory capacity. Importantly, NIRS further provides the opportunity to investigate non-invasively the role of maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity in progressively deteriorating conditions such as ageing and neuromuscular diseases, particularly in human patients.

In the present investigation, we found an ∼2-fold range in the mitochondrial respiratory capacity of the participants. Several biological and environmental factors probably contribute to the considerable range. We did not quantitatively assess physical activity levels or whole-body maximal oxygen uptake in these participants, but it is likely that fitness levels varied considerably. Previous reports in both animal models and humans have demonstrated both a greater mitochondrial density and respiratory capacity in trained versus sedentary organisms (Holloszy, 1967; Gollnick et al. 1972, 1973; McCully et al. 1989; Jackman & Willis, 1996; Brizendine et al. 2013). Some reports support an ageing effect on mitochondria (Conley et al. 2000a,b2000b; Figueiredo et al. 2008; Layec et al. 2013), while others suggest declines in respiratory capacity with age may be more closely associated with reduced physical activity levels (Larsen et al. 2012a,b2012b). Note that while the participants in the present study had an ∼2-fold range in age (18–44 years), most would consider this group relatively young to middle-aged, thereby suggesting that the influence of ageing is likely to be small.

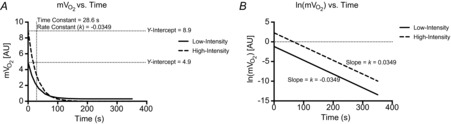

It has been known for many years that oxygen consumption rates in skeletal muscle increase exponentially in response to step increases in work at submaximal intensities (Hill, 1940; Mahler, 1985). During this temporary state of mismatch between oxidative ATP production and ATP hydrolysis, energy supply is met through the breakdown of phosphocreatine (PCr). After cessation of contractile activity, the PCr is restored and the ATP used for resynthesis is almost exclusively derived from oxidative phosphorylation (Quistorff et al. 1993; Forbes et al. 2009). Several metabolic models have been proposed to make inferences about maximal oxidative ATP synthesis during the recovery of exercise (i.e. state 3 to state 4 transition): (1) the kinetic ADP control model is described by the hyperbolic relationship between the concentration of ADP and oxidative ATP synthesis rate (i.e. feedback control by ADP) (Chance & Williams, 1955; Chance et al. 1985); (2) the non-equilibrium thermodynamic model of the linear relationship between ATP synthesis and free energy of ATP hydrolysis (ΔGATP) (Meyer, 1988); and (3) the linear model in which ATP synthesis capacity can be inferred simply from the rate constant for the recovery of mVO2 or PCr (Kemp et al. 2014; Prompers et al. 2014). The NIRS method described here utilizes the linear modelling approach, in which the rate constant for the recovery of mVO2 is used as an index of mitochondrial ATP synthesis capacity (i.e. respiratory capacity). If the recovery kinetics are monoexponential, the data from the origin (in this case maximal mVO2, or [PCr] of zero) to the end-exercise point will lie on a straight line whose slope is equal to the rate constant (Fig. 4). Importantly, this linear model predicts that the rate of recovery is independent of exercise intensity (i.e. starting level), which has been supported by experimental evidence (Meyer, 1988; Binzoni et al. 1992; Walter et al. 1997; Forbes et al. 2009; Ryan et al. 2013a).

Figure 4.

Simulated data in which the starting, end-exercise, value (y-intercept) is altered

A, monoexponential recovery kinetics are such that the initial value has no influence on the change over time (i.e. time and rate constants are the same despite an ∼2-fold difference between starting values). B, the natural log of mVO2 in A plotted against time, in which the slope of the line is equal to the rate constant of the exponential function. Clearly, the two simulated data sets produce equal slopes (parallel lines).

In conclusion, the results of the present study provide support for the validity of NIRS as a tool for assessing in vivo skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity, as NIRS was correlated and in close agreement with the mitochondrial respiratory capacity measured in permeabilized fibres using high-resolution respirometry. These findings provide clear evidence that NIRS can be effectively used to characterize skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiratory capacity non-invasively.

Glossary

- ETS

electron transport system

- HHb

deoxygenated haemoglobin and myoglobin

- mVO2

muscle oxygen consumption

- NIRS

near-infrared spectroscopy

- PCr

phosphocreatine

- PmFBs

permeabilized fibre bundles

- 31P-MRS

31phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- O2Hb

oxygenated haemoglobin and myoglobin

- StO2

tissue saturation

- tHB

total haemoglobin and myoglobin

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

T.E.R. researched the data, contributed to the discussion, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. P.B. researched the data. C.L. researched the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.C.H. contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. P.D.N. contributed to the discussion, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by NIH DK074825 (P.D.N.).

References

- Belardinelli R, Barstow TJ, Nguyen P, Wasserman K. Skeletal muscle oxygenation and oxygen uptake kinetics following constant work rate exercise in chronic congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:1319–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binzoni T, Ferretti G, Schenker K, Cerretelli P. Phosphocreatine hydrolysis by 31P-NMR at the onset of constant-load exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1992;73:1644–1649. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J, Koppo K, Barstow TJ, Bouckaert J. Pattern of deoxy[Hb+Mb] during ramp cycle exercise: influence of aerobic fitness status. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:851–859. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0969-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boushel R, Langberg H, Green S, Skovgaard D, Bulow J, Kjaer M. Blood flow and oxygenation in peritendinous tissue and calf muscle during dynamic exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2000;524:305–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435:297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer ME, Koopman WJ, Koene S, Nooteboom M, Rodenburg RJ, Willems PH, Smeitink JA. The role of mitochondrial OXPHOS dysfunction in the development of neurologic diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;51:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizendine JT, Ryan TE, Larson RD, McCully KK. Skeletal muscle metabolism in endurance athletes with near-infrared spectroscopy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:869–875. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827e0eb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Im J, Nioka S, Kushmerick M. Skeletal muscle energetics with PNMR: personal views and historic perspectives. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:904–926. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Leigh JS, Clark BJ, Maris J, Kent J, Nioka S, Smith D. Control of oxidative-metabolism and oxygen delivery in human skeletal-muscle – a steady-state analysis of the work energy-cost transfer-function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:8384–8388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. III. The steady state. J Biol Chem. 1955;217:409–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen PM, Jubrias SA, Distefano G, Amati F, Mackey DC, Glynn NW, Manini TM, Wohlgemuth SE, Leeuwenburgh C, Cummings SR, Newman AB, Ferrucci L, Toledo FG, Shankland E, Conley KE, Goodpaster BH. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial energetics are associated with maximal aerobic capacity and walking speed in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:447–455. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Mitochondrial oxidative capacity in vivo declines with age in human muscle. Faseb J. 2000a;14:A49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Oxidative capacity and ageing in human muscle. J Physiol. 2000b;526:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MT, Kushmerick MJ. Chemical energetics of slow- and fast-twitch muscles of the mouse. J Gen Physiol. 1982;79:147–166. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblasi RA, Ferrari M, Natali A, Conti G, Mega A, Gasparetto A. Noninvasive measurement of forearm blood-flow and oxygen-consumption by near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1388–1393. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson ML, Ryan TE, Young HJ, McCully KK. Near-infrared assessments of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in persons with spinal cord injury. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:2275–2283. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2657-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Mathalib M, Quaresima V. The use of near-infrared spectroscopy in understanding skeletal muscle physiology: recent developments. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2011;369:4577–4590. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo PA, Ferreira RM, Appell HJ, Duarte JA. Age-induced morphological, biochemical, and functional alterations in isolated mitochondria from murine skeletal muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:350–359. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SC, Paganini AT, Slade JM, Towse TF, Meyer RA. Phosphocreatine recovery kinetics following low- and high-intensity exercise in human triceps surae and rat posterior hindlimb muscles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R161–R170. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90704.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnaiger E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1837–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollnick PD, Armstrong RB, Saltin B, Saubert CWt, Sembrowich WL, Shepherd RE. Effect of training on enzyme activity and fibre composition of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1973;34:107–111. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.34.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollnick PD, Armstrong RB, Saubert CW, Piehl K, Saltin B. Enzyme activity and fibre composition in skeletal muscle of untrained and trained men. J Appl Physiol. 1972;33:312–319. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi B, Pogliaghi S, Rampichini S, Quaresima V, Ferrari M, Marconi C, Cerretelli P. Muscle oxygenation and pulmonary gas exchange kinetics during cycling exercise on-transitions in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:149–158. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00695.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaoka T, Iwane H, Shimomitsu T, Katsumura T, Murase N, Nishio S, Osada T, Kurosawa Y, Chance B. Noninvasive measures of oxidative metabolism on working human muscles by near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1410–1417. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.3.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson NB, Piantadosi CA. Near infrared monitoring of human skeletal muscle oxygenation during forearm ischemia. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2449–2457. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DK. The time course of the oxygen consumption of stimulated frog's muscle. J Physiol. 1940;98:207–227. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1940.sp003845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:2278–2282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman MR, Willis WT. Characteristics of mitochondria isolated from type I and type IIb skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C673–678. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.2.C673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science. 1977;198:1264–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.929199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johri A, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:619–630. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.192138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp GJ, Ahmad RE, Nicolay K, Prompers JJ. Quantification of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function by P magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques: a quantitative review. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014 doi: 10.1111/apha.12307. doi: 10.1111/alpha.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Bhagra S, Nair KS, Port JD. Measurement of human skeletal muscle oxidative capacity by 31P-MR spectroscopy: a cross-validation with in vitro measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:1143–1150. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza IR, Nair KS. Functional assessment of isolated mitochondria in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 2009;457:349–372. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05020-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RG, Callahan DM, Foulis SA, Kent-Braun JA. Age-related changes in oxidative capacity differ between locomotory muscles and are associated with physical activity behaviour. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012a;37:88–99. doi: 10.1139/h11-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S, Hey-Mogensen M, Rabol R, Stride N, Helge JW, Dela F. The influence of age and aerobic fitness: effects on mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012b;205:423–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2012.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson-Meyer DE, Newcomer BR, Hunter GR, Joanisse DR, Weinsier RL, Bamman MM. Relation between in vivo and in vitro measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/mus.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layec G, Bringard A, Le Fur Y, Vilmen C, Micallef J-P, Perrey S, Cozzone PJ, Bendahan D. Comparative determination of energy production rates and mitochondrial function using different 31P MRS quantitative methods in sedentary and trained subjects. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:425–438. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layec G, Haseler LJ, Richardson RS. Reduced muscle oxidative capacity is independent of O2 availability in elderly people. Age (Dordr) 2013;35:1183–1192. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9442-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler M. First-order kinetics of muscle oxygen consumption, and an equivalent proportionality between QO2 and phosphorylcreatine level. Implications for the control of respiration. J Gen Physiol. 1985;86:135–165. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagoni AM, Felisatti M, Mandini S, Mascoli F, Manfredini R, Basaglia N, Zamboni P, Manfredini F. Resting muscle oxygen consumption by near-infrared spectroscopy in peripheral arterial disease: a parameter to be considered in a clinical setting? Angiology. 2010;61:530–536. doi: 10.1177/0003319710362975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully KK, Boden BP, Tuchler M, Fountain MR, Chance B. Wrist flexor muscles of elite rowers measured with magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:926–932. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.3.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully KK, Fielding RA, Evans WJ, Leigh JS, Jr, Posner JD. Relationships between in vivo and in vitro measurements of metabolism in young and old human calf muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:813–819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RA. A linear-model of muscle respiration explains monoexponential phosphocreatine changes. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:C548–553. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.254.4.C548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motobe M, Murase N, Osada T, Homma T, Ueda C, Nagasawa T, Kitahara A, Ichimura S, Kurosawa Y, Katsumura T, Hoshika A, Hamaoka T. Noninvasive monitoring of deterioration in skeletal muscle function with forearm cast immobilization and the prevention of deterioration. Dyn Med. 2004;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1476-5918-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T, Hamaoka T, Sako T, Murakami M, Kime R, Homma T, Ueda C, Ichimura S, Katsumura T. A practical indicator of muscle oxidative capacity determined by recovery of muscle O2 consumption using NIR spectroscopy. Eur J Sport Sci. 2003;3:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Paganini AT, Foley JM, Meyer RA. Linear dependence of muscle phosphocreatine kinetics on oxidative capacity. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C501–C510. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CG, Kane DA, Lanza IR, Neufer PD. Methods for assessing mitochondrial function in diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:1041–1053. doi: 10.2337/db12-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CG, Kane DA, Lin CT, Kozy R, Cathey BL, Lark DS, Kane CL, Brophy PM, Gavin TP, Anderson EJ, Neufer PD. Inhibiting myosin-ATPase reveals a dynamic range of mitochondrial respiratory control in skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 2011;437:215–222. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prompers JJ, Wessels B, Kemp GJ, Nicolay K. Mitochondria: investigation of in vivo muscle mitochondrial function by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;50:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistorff B, Johansen L, Sahlin K. Absence of phosphocreatine resynthesis in human calf muscle during ischaemic recovery. Biochem J. 1993;291:681–686. doi: 10.1042/bj2910681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TE, Brizendine JT, McCully KK. A comparison of exercise type and intensity on the noninvasive assessment of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function using near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 2013a;114:230–237. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01043.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TE, Erickson ML, Brizendine JT, Young HJ, McCully KK. Noninvasive evaluation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity with near-infrared spectroscopy: correcting for blood volume changes. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:175–183. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00319.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TE, Southern WM, Brizendine JT, McCully KK. Activity-induced changes in skeletal muscle metabolism measured with optical spectroscopy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013b;45:2346–2352. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829a726a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan TE, Southern WM, Reynolds MA, McCully KK. A cross-validation of near-infrared spectroscopy measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity with phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 2013c;115:1757–1766. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00835.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvadego D, Domenis R, Lazzer S, Porcelli S, Rittweger J, Rizzo G, Mavelli I, Simunic B, Pisot R, Grassi B. Skeletal muscle oxidative function in vivo and ex vivo in athletes with marked hypertrophy from resistance training. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114:1527–1535. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00883.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert EL, Bastianelli M, Aguer C, Moffat C, Estey C, Koch LG, Britton SL, Harper ME. Intrinsic aerobic capacity correlates with greater inherent mitochondrial oxidative and H2O2 emission capacities without major shifts in myosin heavy chain isoform. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:1624–1634. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01475.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiyama A, Hazeki O, Tamura M. Noninvasive quantitative analysis of blood oxygenation in rat skeletal muscle. J Biochem. 1988;103:419–424. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beekvelt MC, Colier WN, Wevers RA, Van Engelen BG. Performance of near-infrared spectroscopy in measuring local O2 consumption and blood flow in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2001a;90:511–519. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.2.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beekvelt MCP, Borghuis MS, Engelen BGM, Wevers RA, Colier WN. Adipose tissue thickness affects in vivo quantitative near-IR spectroscopy in human skeletal muscle. Clin Sci. 2001b;101:21–28. doi: 10.1042/cs20000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorgerd M, Schols L, Hardt C, Ristow M, Epplen JT, Zange J. Mitochondrial impairment of human muscle in Friedreich ataxia in vivo. Neuromuscul Disord. 2000;10:430–435. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC. A mitochondrial bioenergetic etiology of disease. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1405–1412. doi: 10.1172/JCI61398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter G, Vandenborne K, McCully KK, Leigh JS. Noninvasive measurement of phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in single human muscles. Am J Physiol. 1997;41:C525–C534. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]