Abstract

Intracerebroventricular infusion of a mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) or angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) blocker in rats attenuates sympathetic hyperactivity and progressive left ventricular (LV) dysfunction post myocardial infarction (MI). The present study examined whether knockdown of MRs or AT1Rs specifically in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) contributes to these effects, and compared cardiac effects with those of systemic treatment with the β1-adrenergic receptor blocker metoprolol. The PVN of rats was infused with adeno-associated virus carrying small interfering RNA against either MR (AAV-MR-siRNA) or AT1R (AAV-AT1R-siRNA), or as control scrambled siRNA. At 4 weeks post MI, AT1R but not MR expression was increased in the PVN, excitatory renal sympathetic nerve activity and pressor responses to air stress were enhanced, and arterial baroreflex function was impaired; LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) was increased and LV peak systolic pressure (LVPSP), ejection fraction (EF) and dP/dtmax decreased. AAV-MR-siRNA and AAV-AT1R-siRNA both normalized AT1R expression in the PVN, similarly ameliorated sympathetic and pressor responses to air stress, largely prevented baroreflex desensitization, and improved LVEDP, EF and dP/dtmax as well as cardiac interstitial (but not perivascular) fibrosis. In a second set of rats, metoprolol at 70 or 250 mg kg−1 day−1 in the drinking water for 4 weeks post MI did not improve LV function except for a decrease in LVEDP at the lower dose. These results suggest that in rats MR-dependent upregulation of AT1Rs in the PVN contributes to sympathetic hyperactivity, and LV dysfunction and remodelling post MI. In rats, normalizing MR–AT1R signalling in the PVN is a more effective strategy to improve LV dysfunction post MI than systemic β1 blockade.

Key points

Central mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) activation play a critical role in sympathetic hyperactivity and progressive left ventricle (LV) remodelling and dysfunction after a myocardial infarction (MI).

Intra-paraventricular nucleus (PVN) infusion of adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying small interfering RNA (siRNA) against MR (AAV-MR-siRNA) markedly decreases both MR and AT1R expression in the PVN post MI, whereas AAV-AT1aR-siRNA only decreases AT1R expression. Both AAVs largely prevent sympathetic hyperactivity and inhibit part of LV remodelling and dysfunction post MI.

These findings indicate that enhanced MR–AT1R signalling in the PVN is critical for sympathetic hyperactivity post MI, and contributes to part of LV dysfunction post MI.

Introduction

Increased activity of the brain renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system contributes to sympathetic hyperactivity (DiBona et al. 1995; Francis et al. 2001; Huang et al. 2009b; Zheng et al. 2009), and left ventricle (LV) remodelling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction (MI) (Wang et al. 2004; Lal et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2007, 2009b). Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusion of an aldosterone synthase inhibitor (Huang et al. 2009b), mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) blocker (Francis et al. 2001; Lal et al. 2004) or angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) blocker (DiBona et al. 1995; Huang et al. 2007) all prevent sympathetic hyperactivity (DiBona et al. 1995; Francis et al. 2001; Huang et al. 2007) and improve cardiac remodelling and performance (Huang et al. 2007, 2009b).

In rats post MI, AT1R expression increases in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (Tan et al. 2004; Wei et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2009) and sympatho-excitatory responses to intra-PVN injection of angiotensin II (Ang II) are enhanced as well as sympatho-inhibition by the AT1R blocker losartan (Zheng et al. 2009). The firing rate of neurons in the PVN increases in rats post MI, and forebrain-directed intracarotid artery injection of the AT1R blocker losartan or the MR blocker spironolactone reduces the firing rate (Zhang et al. 2002). In mice post MI, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 (Nox4) is upregulated in the PVN, and chronic silencing of Nox4 by intra-PVN injection of adenovirus-mediated siRNA against Nox4 improves sympathetic hyperactivity, LV dysfunction and peri-infarct apoptosis (Infanger et al. 2010). These studies suggest that activation of the PVN contributes to sympathetic hyperactivity and LV dysfunction post MI. However, whether this represents increased MR and AT1R activation in the PVN has not yet been studied.

An increase in circulating Ang II is one of the stimuli that post MI contribute to the activation of central angiotensinergic pathways (Leenen, 2007). We recently showed that activation of aldosterone–MR neuromodulatory mechanisms by subcutaneous infusion of Ang II increases angiotensinergic signalling in the PVN (Chen et al. 2014). We hypothesized that in response to the increase in plasma Ang II post MI (Leenen et al. 1999), MR activation increases AT1R signalling in the PVN, is essential for sympathetic hyperactivity, and contributes to LV dysfunction post MI.

To test this hypothesis, in the present study we assessed in rats post MI the effects of knockdown of MRs and AT1Rs in the PVN by bilateral intra-PVN infusion of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated siRNA against MR or AT1aR (AAV-MR-siRNA or AAV-AT1R-siRNA) on: (1) MR and AT1R expression in the PVN and downstream rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM); (2) sympathetic reactivity to stress and arterial baroreflex control of renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) and heart rate (HR); and (3) LV function by echocardiography and Millar catheter, and (4) cardiac histology. To evaluate the impact of normalization of central sympathetic outflow compared to standard therapy, i.e. systemic β1-adrenergic receptor blockade (Bristow, 2011), we also assessed LV function in rats post MI treated with the specific β1-adrenergic receptor blocker metoprolol.

Methods

Ethical approval

All experiments were approved by the University of Ottawa Animal Care Committee, and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (8th Edition, 2011).

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 200–250 g were obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Montreal, Quebec, Canada), housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle at constant room temperature, and provided with a standard laboratory chow (120 μmol Na+ g–1) and tap water ad libitum. For all surgeries, rats were anaesthetized with 2–3% isoflurane in oxygen. For rats in the experiment evaluating the effects of metoprolol, slow release buprenorphine (1 mg kg−1) was injected subcutaneously (s.c.) 30 min before surgery, which provides adequate analgesia for 3 days. For other rats, regular buprenorphine (0.04 mg kg−1) was injected s.c. 30 min before each surgery, and twice daily for the following 3 days. Post-operatively, after chest closure in layers, isoflurane was stopped and rats remained ventilated with oxygen until they started breathing on their own. Rats were then placed in a temporary cage, which was ventilated with oxygen, and provided with Transgel (ClearH2O, Portland, ME, USA) and Cheerios (General Mills, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Two to three hours later, they were transferred to their regular cages.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)

AAV-MR-siRNA, AAV-AT1R-siRNA or control vector AAV carrying scrambled siRNA (AAV-SCM-siRNA) were purchased from GeneDetect (Bradenton, FL, USA). The siRNA sequence for MR is 5′-CCAACAAGGAAGCCTGAGC-3′ (position in gene sequence: nucleotide 842–860) (Wang et al. 2006), and for AT1aR is 5′-AAAGGCCAAGTCCCACTCAAG-3′ (position in gene sequence: nucleotide 966–987) (Vázquez et al. 2005). All three viral vectors contained enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). The viral vectors were diluted with sterilized aCSF, and infused at a rate of 0.1 μl min−1 for 10 min for intra-PVN infusion of 5.0 × 107 (MR-siRNA) and 25 × 107 (AT1aR-siRNA) genomic particles. Bilateral intra-PVN infusion of AAV-MR-siRNA or AAV-AT1aR-siRNA at these amounts causes 60–70% knockdown of MR or AT1R expression in the PVN without affecting expression in other nuclei such as the subfornical organ (SFO) and supraoptic nucleus (SON) and prevents most of the hypertension caused by s.c. infusion of Ang II at 500 ng kg−1 min−1 (Chen et al. 2014).

Experimental protocol 1: effects of intra-PVN infusion of AAV-siRNA

Acute myocardial infarction

After acclimatization for 1 week, rats were intubated and a thoracotomy performed via the 4th intercostal space. A 6-0 silk suture was then passed through the myocardium via an atraumatic needle in the area where the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) originates, and then the LAD was permanently ligated. The chest was closed preceded by lung inflation and followed by air aspiration from the thorax. Sham-operated animals underwent the same procedure, except that the ligature around the coronary artery was not tied. Mortality rate within 48 h following MI surgery was ∼40%. Surviving rats were trained to stay quietly in a small cage allowing back-and-forth movement for 2 h twice a week.

Intra-PVN infusion of AAVs

One or two days after the MI surgery, surviving rats were randomly divided into four groups: (1) sham-operated rats with intra-PVN infusion of AAV-SCM-siRNA; (2) MI rats with intra-PVN infusion of AAV-SCM-siRNA; (3) MI rats with intra-PVN infusion of AAV-AT1R-siRNA; and (4) MI rats with intra-PVN infusion of AAV-MR-siRNA. Rats were anaesthetized and mounted on a stereotaxic frame and two small holes with a diameter of 1 mm were drilled through the top of the skull about 2 mm posterior and 0.5 mm lateral to bregma. A pair of 29 G stainless steel cannulae was then inserted through the holes bilaterally into the PVN 1.8 mm posterior, 0.4 mm lateral and 7.9 mm ventral to bregma. The cannulae were connected to two 10 μl Hamilton micro-syringes via a pair of PE-10 tubes, which were mounted on an infusion pump (model 2400-003, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) for intra-PVN infusion at a rate of 0.1 μl min−1 for 10 min of AAV-SCM-siRNA, AAV-MR-siRNA or AAV-AT1R-siRNA. Infusions were begun 5 min after the cannulae were inserted. The cannulae were left in place for at least 10 min after the infusion and then withdrawn slowly to minimize diffusion up the cannula track (Keen-Rhinehart et al. 2005).

Echocardiography

A Vevo 770 echocardiography system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) with a 12 MHz transducer was used. Briefly, under mild isoflurane anaesthesia, echocardiography was performed at 4 weeks post MI. In M-mode recording, internal dimensions of the LV in systole and diastole were measured, and LV volumes and ejection fraction (EF) were calculated.

Assessment of sympathetic reactivity and baroreflex function

After echocardiography, rats were anaesthetized and catheters (PE-10 fused to PE-50) were placed in the right femoral artery and vein. The left kidney was exposed via a left flank incision, and the renal nerve was hooked to a pair of silver electrodes and glued together with SilGel 604 (Wacker, Munich, Germany) (Huang et al. 2009b). The electrodes and catheters were tunnelled to the back of the neck, and rats were placed in the small cages.

About 4 h after recovery from anaesthesia, the electrodes were connected to a Grass P511 band-pass amplifier and an integrator, and nerve activity (mV), mean arterial pressure (MAP) and HR were acquired by a PC with Grass data acquisition software (Polyview 16) (Natus Medical Inc., Grass Product Brand, Warwick, RI, USA). The noise for RSNA was determined after i.v. injection of phenylephrine (10 μg) to increase MAP by >50 mmHg eliciting a near complete inhibition of RSNA (DiBona et al. 1995), and the remaining activity subtracted from the total activity. After a 20 min stabilization, baseline MAP, HR and RSNA were recorded in resting rats for 10 min. A standardized air-jet stress was then applied for 30 s twice at 10 min intervals, using an air-jet stream (2 lbf in–2 (13.8 kPa)) blowing at 3 cm in front of the face of the rat. Peak increases in RSNA, blood pressure and heart rate from the resting values were recorded, and the mean of the two peak responses was used for statistical analysis. After a 20 min rest, phenylephrine (5–50 μg min−1) was infused i.v. to obtain ramp increases of MAP by 50 mmHg over 1–2 min. Ten minutes after the responses to phenylephrine had subsided, sodium nitroprusside (10–100 μg min−1) was infused i.v. to obtain ramp decreases of MAP by 50 mmHg over 1 min. Responses of RSNA were expressed as percentage of resting values. To evaluate the arterial baroreflex function, changes in RSNA and HR in response to changes in MAP were analysed as a logistic model (DiBona et al. 1995), using the equation RSNA/ΔHR = P1 + P2/{1 + exp[P3(MAP – P4)]}, where P1 is lower RSNA/ΔHR plateau, P2 is RSNA/ΔHR range, P3 is a curvature coefficient, and P4 is MAP50, i.e. the MAP at half the RSNA/ΔHR range.

Assessment of LV haemodynamics

Following the assessment of baroreflex function, rats were anaesthetized and a 2 F high-fidelity micro-manometer catheter (SPR-407; Millar Institute, Houston, TX, USA) was inserted into the LV via the right carotid artery (Ahmad et al. 2008). The Millar catheter was connected to a Harvard Data Acquisition system interfaced with a PC with AcqKnowledge III software (ACQ 3.2) (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA) for measurement of LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), peak systolic pressure (LVPSP), and maximal/minimal first derivative of change in pressure over time (dP/dtmax/min).

Experimental protocol II: effects of systemic blockade of β1-adrenergic receptors

Two days after the MI surgery described in protocol I, rats were randomly divided into four groups: (1) sham-operated rats; (2) MI rats without treatment; (3) MI rats with metoprolol at 70 mg kg−1 day−1 in drinking water; and (4) MI rats with metoprolol at 250 mg kg−1 day−1) in drinking water. Metoprolol was dissolved in the drinking water at concentrations to provide a low or high degree of β1 blockade (Wei et al. 2000; Xydas et al. 2006). Twenty-four-hour water intake and weekly body weight were measured and the metoprolol concentration in the drinking water was adjusted accordingly. Echocardiography was performed at 2 and 4 weeks post MI. LV haemodynamics were assessed at 4 weeks post MI.

Brain tissue collection for mRNA

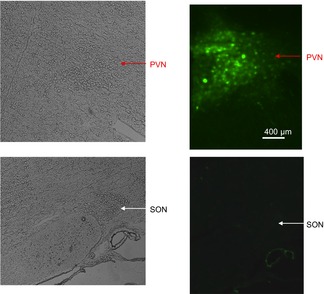

In protocol I, after assessment of LV function, under anaesthesia rats were perfused transcardially with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated PBS. Whole brains were removed, rapidly frozen in −20 to −30°C pre-cooled methylbutane and stored at −80°C until use. For the PVN, RVLM and SFO, serial 100 μm sections were cut (for the PVN, 10–12 sections within 0.92–2.12 mm posterior to bregma), kept on cold glass slides and stored on dry ice for micro-punching. For assessment of siRNA expression, 5–7 10 μm sections (for the PVN, within 1.82–1.92 mm posterior to bregma) were cut for green fluorescent protein (GFP) imaging. For all 10 μm sections, the GFP fluorescence was observed under a ZEISS AX10 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany). When the fluorescence was detected only in the PVN on the 10 μm sections (Fig. 1), micro-punching of tissue was performed on the 100 μm sections from the same rat for mRNA assessment, as described previously (Wang et al. 2010). The overall success rate of bilateral intra-PVN infusion, with GFP staining solely in the PVN, was ∼75%, and rats with incorrect infusion sites were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

GFP fluorescence in the PVN after intra-PVN AAV infusion in rat post MI

Representative image of eGFP fluorescence in the PVN. eGFP expression was evaluated in brain sections of a rat infused in the PVN with AAV-AT1aR-siRNA at 25 × 107 genomic particles. Red arrows indicate the PVN and white arrows point to the SON.

Real-time RT-PCR for MR and AT1R mRNA

DNase I-treated total RNA (500 ng) was used for cDNA synthesis by incubation with 200 U Superscript II RNase H reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada) at 42°C for 50 min. The primers, PCR conditions and external standards for MR, AT1R and the housekeeping gene phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK 1) were the same as previously described (Wang et al. 2010). Real-time PCR was performed using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I (Roche Diagnostics, QC, Canada). The PCR conditions were set as follows: an initial step at 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s; annealing at 62°C for 10 s; and extension at 72°C for 15 s. Expression was normalized to PGK 1 levels as an endogenous reference.

Cardiac histology

The hearts were collected immediately after the assessment of LV function, rinsed in ice-cold 0.9% saline, and the right ventricle was separated from the LV. The LV was cut through the septum using ice-cold scissors and 2–3 additional smaller incisions were made close to the apex to flatten the LV. A transparent sheet was placed on top of the flattened LV and the borders between the infarcted and non-infarcted area traced with a sharp permanent marker, and measured by planimetry to calculate the infarct size. Rats with MI sizes <20% were excluded from the study. The tissues were then blotted dry, weighed and stored in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. To assess cardiac fibrosis, mid-level sections of the ventricles (4 μm thick) were stained with Sirius red F3BA (0.5% in saturated aqueous picric acid) as described previously (Lal et al. 2004, 2005). The images were captured randomly (magnification: ×40 for perivascular area and ×20 for others) using a standard polarizing filter and Adobe Photoshop 4.0 imaging software, and analysed using Image-Pro Plus 4.1 imaging software. Fibrosis in the peri-infarct area (2 mm outside the infarct) and at the septum as distant fibrosis, were measured separately. In each area, about 7–10 images for interstitial fibrosis were analysed, and average values were calculated for each rat.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons with Student–Newman–Keuls test was used to determine the effects of treatments on the various parameters. Statistical significance for all analyses was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Knockdown of PVN MR or AT1R expression

There were no significant differences in body weight among the four groups of rats at 4 weeks after sham or MI surgery (Table 1). MI size was in the 30% range and similar among the three groups of MI rats. Baseline MAP was significantly lower and HR significantly higher in rats post MI treated with SCM-siRNA but not with AT1R- or MR-siRNA, compared with sham rats. LV weights tended to be higher in MI rats, but did not differ significantly in the three groups of MI rats. Right ventricle (RV) weights were increased in MI rats with SCM-siRNA. This increase was attenuated in rats with MR-siRNA but not AT1R-siRNA.

Table 1.

Resting MAP and HR, infarct size, heart weight, and baroreflex parameters at 4 weeks post MI in sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA

| MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | SCM-siRNA | AT1R-siRNA | MR-siRNA | |

| n | 10 | 7 | 9 | 9 |

| Body weight (BW; g) | 425 ± 10 | 414 ± 10 | 385 ± 13 | 424 ± 11 |

| MI size (%) | — | 30 ± 3 | 31 ± 2 | 26 ± 2 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 111 ± 2 | 99 ± 3* | 107 ± 3 | 108 ± 3 |

| HR (beats min–1) | 394 ± 6 | 435 ± 9* | 420 ± 9 | 402 ± 6 |

| LV weight (mg (100 g BW)–1) | 204 ± 7 | 218 ± 7 | 219 ± 10 | 215 ± 4 |

| RV weight (mg (100 g BW)–1) | 53 ± 2 | 78 ± 8* | 71 ± 7* | 61 ± 2† |

| Reflex control of RSNA | ||||

| Maximal slope (% mmHg–1) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1* | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| Range (%) | 182 ± 4 | 142 ± 5* | 149 ± 3* | 169 ± 3*† |

| Reflex control of HR | ||||

| Maximal slope (beats min–1 mmHg−1) | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1* | 2.0 ± 0.1*‡ | 2.0 ± 0.1*‡ |

| Range (beats min–1) | 228 ± 6 | 172 ± 13* | 200 ± 11 | 199 ± 9 |

Data are means ± SEM. For MAP, F = 7.1, P < 0.01. For HR, F = 10.1, P < 0.01. For RV weight, F = 3.98, P < 0.05. Reflex control of RSNA: for maximal slope, F = 20.7, P < 0.0001; for range, F = 44.6, P < 0.0001. Reflex control of HR: for maximal slope, F = 51.0, P < 0.0001; for range, F = 4.9, P < 0.01.

P < 0.05 vs. sham;

P < 0.05 vs. MI + SCM-siRNA or MI + AT1R-siRNA.

P < 0.05 vs. MI + SCM-siRNA.

AT1R and MR expression in the PVN, RVLM and SFO

Four weeks after MI, AT1R mRNA expression in the PVN in rats treated with control AAV-SCM-siRNA was significantly increased by ∼75% compared with sham rats. Intra-PVN infusion of AAV-MR-siRNA or AAV-AT1aR-siRNA both prevented the MI-induced increases in AT1R expression in the PVN, AAV-AT1aR-siRNA being somewhat more effective (Fig. 2A). MR expression in the PVN did not change in rats post MI versus sham rats. Intra-PVN infusion of AAV-MR-siRNA decreased MR mRNA expression by 65%, whereas intra-PVN infusion of AAV-AT1aR-siRNA did not significantly decrease MR expression in the PVN (Fig. 2B). In the RVLM, MR and AT1R mRNA expression were increased by 40 and 80% post MI, respectively. AAV-MR-siRNA infusion in the PVN had no effect on the MI-induced MR and AT1R upregulation in the RVLM (Fig. 2C and D). There were no differences in MR and AT1R mRNA expression in the SFO between sham rats and rats post MI treated with AAV-SCM-siRNA, -MR-siRNA or -AT1aR-siRNA (for MR (× 10−2): 7.2 ± 0.5, 7.8 ± 0.3, 8.1 ± 0.7 and 7.4 ± 0.9 MR/PGK 1, P = 0.8; for AT1R (× 10−1): 1.4 ± 0.1, 1.4 ± 0.1, 1.5 ± 0.1 and 1.5 ± 0.1 AT1R/PGK 1, P = 0.9).

Figure 2.

MR and AT1R mRNA expression

MR and AT1R mRNA expression at 4 weeks post MI in the PVN (A and B) and RVLM (C and D) in sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA. Data are means ± SEM. Some RVLM samples from the AT1R-siRNA group were lost, and not enough data are available for this group. PVN (n = 7–8 per group): for AT1R, F = 16.7, P < 0.0001; for MR, F = 10.5, P < 0.0001. RVLM (n = 4–7 per group): for AT1R, F = 13.4, P < 0.001; for MR, F = 4.59, P < 0.05. *P < 0.05 vs. others; aP < 0.05 vs. MI + MR-siRNA.

Sympathetic reactivity

Maximal increases in MAP, RSNA and HR in response to air-jet stress were increased by 150–200% in rats post MI treated with SCM-siRNA (Fig. 3). Treatment with MR- or AT1R-siRNA normalized blood pressure responses to air-jet stress and significantly attenuated the MI-induced enhancement in RSNA and HR. The extent of attenuation was similar in rats treated with MR- versus AT1R-siRNA.

Figure 3.

Responses to air stress

Increases in MAP, RSNA and HR in response to air stress at 4 weeks post MI in sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA. Data are means ± SEM (n = 7–10 per group). For MAP, F = 12.7, P < 0.00001; for RSNA, F = 7.5, P < 0.001; for HR, F = 8.1, P < 0.001. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; aP < 0.05 vs. MI + SCM-siRNA.

In rats post MI treated with SCM-siRNA, the curves of baroreflex control of RSNA and HR were less steep with significantly smaller maximal slopes and ranges, consistent with impaired baroreflex function (Fig. 4, Table 1). Intra-PVN infusion of MR- or AT1R-siRNA similarly improved the maximal slope of baroreflex control of both RSNA and HR. Whereas treatment with MR-siRNA improved ranges of both RSNA and HR changes, treatment with AT1R-siRNA normalized the range of HR but not RSNA changes (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Arterial baroreflex

Arterial baroreflex control of RSNA (upper panel) and HR (lower panel) analysed as a logistic model at 4 weeks post MI in sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA. For statistics and n, see Table 1.

LV dimensions and function

At 4 weeks post MI, MI rats treated with SCM-siRNA showed significant increases in LV systolic and diastolic internal dimensions and decreases in EF. Intra-PVN infusion of MR-siRNA and AT1R-siRNA both improved LV diastolic and systolic dimensions, but only significantly for AT1R-siRNA. The MI-induced decrease in EF was improved similarly by AT1R- and MR-siRNA (Fig. 5). At 4 weeks post MI, MI rats with SCM-siRNA demonstrated a significant increase in LVEDP and decreases in LVPSP and dP/dtmax (Fig. 6). Intra-PVN infusion of AT1R-siRNA and MR-siRNA similarly significantly improved LVEDP and dP/dtmax. Only intra-PVN infusion of MR-siRNA significantly attenuated the MI-induced decrease in LVPSP.

Figure 5.

LV dimensions and ejection fraction

LV diastolic and systolic dimensions, and ejection fraction measured by echocardiography at 4 weeks post MI in sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA. Data are means ± SEM (n = 7–9 per group). For the LV diastolic dimension, F = 9.02, P < 0.001; for the LV systolic dimension, F = 20.6, P < 0.0001; for ejection fraction, F = 26.1, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; aP < 0.05 vs. MI + SCM-siRNA.

Figure 6.

LV function

LV function measured by Millar catheter at 4 weeks post MI in sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA. Data are means ± SEM (n = 7–10 per group). For LVEDP, F = 11.9, P < 0.0001; for LVPSP, F = 6.69, P < 0.002; For dP/dtmax, F = 34.6, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; aP < 0.05 vs. MI + SCM-siRNA.

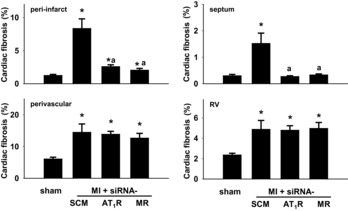

Cardiac fibrosis

At 4 weeks post MI, increased interstitial fibrosis was apparent in the peri-infarct area, septum, RV and around the coronary arteries (Figs 9 9). The increase was most pronounced in the peri-infarct area. Intra-PVN AAV-AT1R- or AAV-MR-siRNA similarly attenuated the interstitial fibrosis in the peri-infarct area and prevented the fibrosis in the septum, but had no effects on the fibrosis in the RV or around the coronary arteries.

Figure 7.

Fibrosis in peri-infarct area

Representative images of interstitial fibrosis in the peri-infarct area of the LV at 4 weeks post MI in rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA.

Figure 9.

Cardiac fibrosis

Interstitial fibrosis in peri-infarct area of the LV, septum and RV, and perivascular fibrosis in LV at 4 weeks post MI of sham rats and rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA. Data are means ± SEM (n = 5–7 per group). For peri-infarct, F = 19.3, P < 0.0001; for perivascular, F = 4.73, P < 0.01; for septum, F = 11.8, P < 0.0001; for RV, F = 4.1, P < 0.02. *P < 0.05 vs. sham; aP < 0.05 vs. MI + SCM-siRNA.

Figure 8.

Perivascular fibrosis

Representative images of perivascular fibrosis in the LV at 4 weeks post MI of sham rats or rats treated post MI with intra-PVN infusion of scrambled (SCM)-siRNA, MR-siRNA or AT1R-siRNA.

Effects of metoprolol

There were no significant differences in body weight among the four groups of rats, or in MI size among the three groups of MI rats at 4 weeks after MI surgery (Table 2). When normalized by body weight, there were no significant differences in LV and RV weights among the four groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

LV dimensions and ejection fraction assessed by echocardiography in sham rats and rats drinking tap water (vehicle) or water containing metoprolol (Met) at 70 or 250 mg kg−1 day−1 for 2 and 4 weeks post MI

| MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 11) | Vehicle (n = 8) | Met 70 (n = 7) | Met 250 (n = 7) | |

| 2 weeks | ||||

| SD (mm) | 2.9 ± 0.2* | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.3 |

| DD (mm) | 7.2 ± 0.3* | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 8.8 ± 0.2 |

| EF (%) | 87 ± 1* | 59 ± 2 | 65 ± 3 | 63 ± 4 |

| 4 weeks | ||||

| SD (mm) | 3.7 ± 0.3* | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.3 |

| DD (mm) | 8.0 ± 0.2* | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 9.9 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 0.3 |

| SV/100 g BW (μl (100 g)–1) | 16 ± 3* | 41 ± 3 | 50 ± 9 | 50 ± 7 |

| DV/100 g BW (μl (100 g)–1) | 89 ± 6* | 116 ± 6 | 129 ± 11 | 126 ± 9 |

| EF (%) | 83 ± 2* | 60 ± 2 | 62 ± 2 | 61 ± 3 |

| BW (g) | 395 ± 9 | 399 ± 16 | 432 ± 13 | 403 ± 9 |

| MI size (%) | — | 31 ± 3 | 27 ± 3 | 34 ± 2 |

Data are means ± SEM. SD, systolic dimension; DD, diastolic dimension; SV, systolic volume; DV, diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; BW, body weight. For 2 weeks: SD, F = 20.6, P < 0.0001; DD, F = 6.36, P < 0.002; EF, F = 30.0, P < 0.0001. For 4 weeks: SD, F = 20.4, P < 0.0001; DD, F = 9.02, P < 0.0002; SV/100 g BW, F = 12.9, P < 0.0001; DV/100 g BW, F = 4.51, P < 0.01; EF, F = 26.1, P < 0.0001.

P < 0.05, vs. others.

Table 3.

LV and RV weight, and LV haemodynamics, in sham rats and rats drinking tap water (vehicle) or water containing metoprolol (Met) at 70 or 250 mg kg−1 day−1 for 4 weeks post MI

| MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 10) | Vehicle (n = 8) | Met 70 (n = 6) | Met 250 (n = 7) | |

| LV/100 g BW (mg (100 g)–1 | 202 ± 5 | 211 ± 3 | 212 ± 5 | 199 ± 6 |

| RV/100 g BW (mg (100 g)–1) | 50 ± 1 | 57 ± 4 | 57 ± 5 | 59 ± 5 |

| LVPSP (mmHg) | 114 ± 2 | 104 ± 2* | 110 ± 4 | 99 ± 2* |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 16.7 ± 1.2* | 8.0 ± 1.9† | 15.0 ± 3.3* |

| dP/dtmax (mmHg s–1) | 7463 ± 127 | 5312 ± 111* | 5823 ± 333* | 4963 ± 254* |

| dP/dtmin (mmHg s–1) | 5733 ± 197 | 4502 ± 176* | 4743 ± 219* | 4106 ± 224* |

| HR (beats min–1) | 359 ± 7 | 372 ± 7 | 355 ± 19 | 299 ± 8† |

Data are means ± SEM. For LVPSP, F = 6.7, P < 0.002. For LVEDP, F = 11.9, P < 0.0001. For dP/dtmax, F = 34.6, P < 0.0001. For dP/dtmin, F = 11.1, P < 0.0001. For HR, F = 8.3, P < 0.001.

P < 0.05 vs. sham,

P < 0.05 vs. others.

At 2 and 4 weeks post MI, LV dimensions and volumes were significantly increased and EF was decreased in MI rats with vehicle. Treatment with metoprolol at either dose had no significant effects on MI-induced changes of these parameters but tended (P = 0.1) to further increase LV diastolic volume per 100 g body weight at 4 weeks post MI (Table 2).

At 4 weeks post MI, resting HR was significantly lower in rats treated with metoprolol at 250 mg kg−1 day−1 but not at 70 mg kg−1 day−1. LVPSP was significantly decreased in MI rats with vehicle or metoprolol at 250 mg kg−1 day−1, and LVEDP was increased compared with sham. Metoprolol at 70 but not 250 mg kg−1 day−1 improved LVEDP compared with vehicle-treated MI rats. LV dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin were significantly lower in rats post MI, and metoprolol at both doses did not significantly improve either (Table 3).

Discussion

As major findings, the present study shows that in rats post MI (1) AT1Rs are upregulated in the PVN and RVLM, but MRs only in the RVLM; (2) intra-PVN infusion of AAV-MR-siRNA normalizes AT1R expression in the PVN but does not affect upregulation in the RVLM; (3) MR or AT1R knockdown in the PVN both largely prevent enhanced sympatho-excitatory and pressor responses to air stress, improve baroreflex function and ameliorate LV dysfunction and part of cardiac remodelling post MI; and (4) oral treatment with the β1-adrenergic receptor blocker metoprolol at 70 but not 250 mg kg−1 day−1 causes modest improvement in LV dysfunction post MI. These findings indicate that in the PVN increased MR signalling, presumably via AT1R activation, plays a critical role in sympathetic hyperactivity post MI. The resulting improvement in LV dysfunction by knockdown of MRs and AT1Rs in the PVN is substantially better than that caused by standard β1-blocker therapy, but less than that caused by i.c.v. infusion of a MR or AT1R blocker.

Numerous studies have demonstrated neuronal activation post MI in brain nuclei involved in cardiovascular and autonomic regulation such as the SFO, PVN and SON (Patel & Zhang, 1996; Vahid-Ansari & Leenen, 1998). Consistent with previous studies (Tan et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2006; Wei et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2012), the present study shows that post MI AT1R mRNA is upregulated in the PVN and RVLM. For the SFO, Wei et al. (2008) reported a 2-fold increase in AT1R expression and we (Tan et al. 2004) showed a 15% increase in AT1R density at 4 weeks post MI, but no increase is apparent in the present study. These different findings may reflect differences in LV dysfunction (Tan et al. 2004) and in plasma Ang II post MI. So far, no study has reported changes in MR expression in brain nuclei post MI. In rats, the hypothalamic content of aldosterone increases post MI (Yu et al. 2008), and i.c.v. infusion of an MR blocker attenuates the AT1R upregulation in the hypothalamus (Yu et al. 2008). The location of the MR or AT1R was not determined. The present study shows that in the PVN and SFO MR expression is not upregulated but enhanced MR signalling appears to contribute to the increased AT1R expression in the PVN (Huang et al. 2011), since knockdown of MR expression prevents the increase in AT1R expression in the PVN. In contrast to the PVN, both MR and AT1R expression increase in the RVLM. Knockdown of MR expression in the PVN did not affect MI-induced AT1R and MR upregulation in the RVLM. This indicates that firstly the knockdown of MRs is localized specifically in the PVN, and secondly that angiotensinergic signalling from the PVN does not contribute to the upregulation of AT1Rs and MRs in the RVLM post MI. It is possible that post MI, aldosterone also increases in the RVLM and plays a functional role in neuronal activation by activating MRs and thereby AT1Rs (Oshima et al. 2013).

Sympatho-excitation is one of the major patho-physiological changes after MI, and i.c.v. infusion of an aldosterone synthase inhibitor (Huang et al. 2009b), MR blocker (Francis et al. 2001; Huang et al. 2009b) or AT1R blocker (DiBona et al. 1995; Huang et al. 2007) prevent sympathetic hyperactivity. Forebrain-directed intracarotid artery injection of an AT1R or MR blocker reduces the firing rate of neurons in the PVN (Zhang et al. 2002). The present study shows that knockdown of MR or AT1R mRNA expression specifically in the PVN prevents enhancement of sympatho-excitatory and pressor responses to air stress and markedly improves arterial baroreflex control of RSNA and HR in rats post MI. The extent of these effects is similar to the effects of i.c.v. infusion of a MR or AT1R blocker (Huang et al. 2007, 2009b). Together, these results indicate that as a major integrating nucleus, the PVN plays a crucial role in the chronic sympatho-excitation after MI. Sympathetic hyperactivity after MI largely normalized despite MRs and AT1Rs in the RVLM remaining upregulated after knockdown of MRs in the PVN. It is possible that enhanced MR–AT1R signalling in the RVLM further amplifies the efferent input from the PVN but does not lead to sympathetic hyperactivity in the absence of enhanced input from the PVN. Further studies are required to clarify the role of MRs and AT1Rs in the RVLM, as well as the role of the SFO for the MR and AT1R activation in the PVN.

i.c.v. infusion of losartan attenuates MI-induced increases in LVEDP and LV dimensions and decreases in LVPSP, dP/dtmax and LV EF by 50–60% (Huang et al. 2009a), and decreases interstitial fibrosis in the peri-infarct area and septum by 40% and 70%, respectively (Huang et al. 2009a). i.c.v. infusion of spironolactone also markedly inhibits the MI-induced increase in LVEDP and decreases in LVPSP and dP/dtmax, normalizes interstitial fibrosis in the septum, RV and peri-vascular areas, and decreases interstitial fibrosis in the LV peri-infarct area by 45% (Lal et al. 2004). In the present study, knockdown of AT1Rs in the PVN attenuated increases in the LV systolic and diastolic dimension by 30–40%, but MR knockdown only ∼10%. Both attenuated MI-induced decreases in EF by 25%, improved LVEDP and dP/dtmax, attenuated fibrosis in the peri-infarct, and normalized fibrosis in the septum. It appears that knockdown of MR or AT1R expression in the PVN causes similar qualitative effects to i.c.v. infusion of an MR or AT1R blocker in terms of improvements of most parameters of LV dysfunction and remodelling post MI, but are not as effective as i.c.v. infusion of the blockers. In the amounts used, MR-siRNA caused a marked decrease in MR mRNA and AT1R-siRNA prevented the increase in AT1R mRNA in the PVN of MI rats, and sympathetic hyperactivity was prevented by both siRNAs. In addition, this degree of knockdown in the PVN also prevents the development of severe hypertension by s.c. infusion of Ang II (Chen et al. 2014). Nonetheless, it is possible that more marked knockdown is needed to normalize other mechanisms regulated by the PVN such as the pituitary–adrenal axis and plasma aldosterone. On the other hand, the siRNA approach provides highly specific and localized gene targeting and we cannot exclude the possibility that the larger effects of i.c.v. infusion of a MR or AT1R blocker represent off-target or direct peripheral effects. Alternatively, these observations may suggest that generalized blockade by i.c.v. infusion of a MR or AT1R blocker is more effective for prevention of sympathetic hyperactivity and/or affects more mechanisms contributing to the progression of LV dysfunction and remodelling post MI. Of particular interest, i.c.v.-administered spironolactone also normalizes MI-induced interstitial fibrosis in the RV and peri-vascular areas (Lal et al. 2004), whereas knockdown of MRs or AT1Rs in the PVN has no effects at all on the fibrosis in these areas. Central infusion of a MR blocker may affect other mechanisms by, for example, causing MR blockade in the SON resulting in inhibition of release of vasopressin (Capone et al. 2012; Teruyama et al. 2012), endothelin (Capone et al. 2012; Kolettis et al. 2013) or aldosterone (Lal et al. 2004, 2005) post MI.

As the most common approach to block cardiac sympathetic activation, β-adrenergic receptor blockers are being used in patients with heart failure, showing benefits such as a decrease in LVEDP and increase in EF, and improved outcome (Bristow, 2011). In rats, oral treatment with a non-specific β-blocker such as propranolol did not improve LVPSP or remodelling and further increased LVEDP post MI (Litwin et al. 1999). Oral administration of the selective β1-blocker metoprolol at 60–250 mg kg−1 day−1 decreased LVEDP (Latini et al. 1998; Omerovic et al. 2003; Maczewski & Mackiewicz, 2008) and increased LV dP/dtmax (Omerovic et al. 2003; Xydas et al. 2006), whereas s.c. infusion of metoprolol at 1 mg kg−1 h−1 attenuated LV dilatation but had no effect on LV dysfunction (Omerovic et al. 2003). In the present study, oral treatment with metoprolol at 70 or 250 mg kg−1 day−1 had no effects on LV dimensions and most parameters of LV function. Treatment with metoprolol at 70 mg kg−1 day−1 significantly lowered the LVEDP, but not at the 250 mg kg−1 day−1 which may reflect the lower heart rate and the longer LV filling time at this dose. It appears that, in rats, metoprolol is somewhat effective in improving LV dysfunction post MI, and its effects may depend on route of administration and doses but appear substantially less than those caused by central blockade of MRs or AT1Rs.

Central blockade of AT1Rs with losartan prevents sympathetic hyperactivity and improves LV function and remodelling after MI substantially better than peripherally administered losartan (Huang et al. 2007). Similarly, both i.c.v. and oral administrations of spironolactone attenuate MI-induced increases in LVEDP and cardiac fibrosis, and ameliorate decreases in LVPSP and dP/dtmax, but the extent of improvement is greater by i.c.v. compared with oral routes (Lal et al. 2004). Together with the findings in the present study, these results indicate that central blockade of MRs or AT1Rs to prevent sympathetic hyperactivity and other contributing mechanisms appears to be a more effective approach for the treatment of progressive heart failure post MI, than systemic treatments.

Limitations of the study

The present study did not examine the cellular or the subdivision localization of the MRs and AT1Rs in the PVN. In the PVN, AT1Rs are predominantly expressed in the parvocellular regions in normal rats (Oldfield et al. 2001) but s.c. Ang II increases the expression in both magnocellular and parvocellular regions (Wei et al. 2009). AT1Rs and MRs are also expressed in brain astrocytes (Füchtbauer et al. 2011), and the functional effects of aldosterone or Ang II in neurons may involve the activation of such non-neuronal AT1Rs and MRs. Further studies are needed to determine the role of MRs and AT1Rs in neurons or glia, and if in neurons, whether in magnocellular versus parvocellular neurons in the PVN.

Conclusions

After MI, enhanced MR–AT1R signalling specifically in the PVN appears to be an essential event responsible for sympathetic hyperactivity, and contributes to LV dysfunction and remodelling. In rats, normalizing MR–AT1R signalling in the PVN appears to be a more effective strategy to improve LV dysfunction post MI than systemic treatment with the β1-adrenergic receptor blocker metoprolol. However, i.c.v. infusion of a MR or AT1R blocker is more effective in inhibiting the dysfunction and remodelling, including the inhibition of perivascular and RV fibrosis, indicating that central MR–AT1R signalling in other nuclei such as the SON controls other peripheral mechanisms affecting the heart post MI.

Glossary

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- AAV-siRNA

adeno-associated virus carrying small interfering RNA

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- AT1R

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- EF

ejection fraction

- eGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- HR

heart rate

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- LV

left ventricle

- LVEDP

LV end-diastolic pressure

- LVPSP

LV peak systolic pressure

- LV dP/dtmax/min

LV maximal/minimal first derivative of change in pressure over time

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MR

mineralocorticoid receptor

- PGK 1

phosphoglycerate kinase 1

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- RSNA

renal sympathetic nerve activity

- RV

right ventricle

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla

- SCM

scrambled

- SFO

subfornical organ

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SON

supraoptic nucleus

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

All experiments were carried out at the Hypertension Unit, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. F.H.H.L. designed experiments, interpreted the data, and revised drafts of the manuscript. B.S.H. and A.C. performed some of the experiments, analysed and interpreted the data, wrote parts of the first draft of the manuscript, and revised further drafts of the manuscript. M.A. performed some of the experiments, calculated data and critically revised drafts of the manuscript. H.-W.W. designed and developed experiments in molecular biology, analysed and interpreted the data, wrote parts of the first draft of the manuscript and revised further drafts. All authors confirm that they have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by operating grant no. FRN:MOP-74432 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. F. H. H. Leenen holds the Pfizer Chair in Hypertension Research, an endowed chair supported by Pfizer Canada, University of Ottawa Heart Institute Foundation, and Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- Ahmad M, White R, Tan J, Huang BS, Leenen FHH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, inhibition of brain and peripheral angiotensin-converting enzymes, and left ventricular dysfunction in rats after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51:565–572. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318177090d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR. Treatment of chronic heart failure with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists: a convergence of receptor pharmacology and clinical cardiology. Circ Res. 2011;109:1176–1194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone C, Faraco G, Peterson JR, Coleman C, Anrather J, Milner TA, Pickel VM, Davisson RL, Iadecola C. Central cardiovascular circuits contribute to the neurovascular dysfunction in angiotensin II hypertension. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4878–4886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6262-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Huang BS, Wang H-W, Ahmad M, Leenen FHH. Knockdown of mineralocorticoid or angiotensin II type 1 receptor gene expression in the paraventricular nucleus prevents angiotensin II hypertension in rats. J Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.275560. (in press) Doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.275560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBona GF, Jones SY, Brooks VL. ANG II receptor blockade and arterial baroreflex regulation of renal nerve activity in cardiac failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1995;269:R1189–R1196. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.5.R1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J, Weiss RM, Wei SG, Johnson AK, Beltz TG, Zimmerman K, Felder RB. Central mineralocorticoid receptor blockade improves volume regulation and reduces sympathetic drive in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2241–H2251. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Füchtbauer L, Groth-Rasmussen M, Holm TH, Løbner M, Toft-Hansen H, Khorooshi R, Owens T. Angiotensin II Type 1 receptor (AT1) signaling in astrocytes regulates synaptic degeneration-induced leukocyte entry to the central nervous system. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BS, Ahmad M, Tan J, Leenen FHH. Sympathetic hyperactivity and cardiac dysfunction post-MI: different impact of specific CNS versus general AT1 receptor blockade. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BS, Ahmad M, Tan J, Leenen FHH. Chronic central versus systemic blockade of AT1 receptors and cardiac dysfunction in rats post-myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009a;297:H968–H975. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00317.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BS, White RA, Ahmad M, Tan J, Jeng AY, Leenen FHH. Central infusion of aldosterone synthase inhibitor attenuates left ventricular dysfunction and remodeling in rats after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2009b;81:574–781. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BS, Zheng H, Tan J, Patel KP, Leenen FHH. Regulation of hypothalamic renin–angiotensin system and oxidative stress by aldosterone. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:1028–1038. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.059840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infanger DW, Cao X, Butler SD, Burmeister MA, Zhou Y, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Silencing nox4 in the paraventricular nucleus improves myocardial infarction-induced cardiac dysfunction by attenuating sympathoexcitation and periinfarct apoptosis. Circ Res. 2010;106:1763–1774. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen-Rhinehart E, Kalra SP, Kalra PS. AAV-mediated leptin receptor installation improves energy balance and the reproductive status of obese female Koletsky rats. Peptides. 2005;26:2567–2578. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolettis TM, Barton M, Langleben D, Matsumura Y. Endothelin in coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Cardiol Rev. 2013;21:249–256. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318283f65a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal A, Veinot JP, Ganten D, Leenen FHH. Prevention of cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction in transgenic rats deficient in brain angiotensinogen. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal A, Veinot JP, Leenen FHH. Critical role of CNS effects of aldosterone in cardiac remodeling post-myocardial infarction in rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latini R, Masson S, Jeremic G, Luvarà G, Fiordaliso F, Calvillo L, Bernasconi R, Torri M, Rondelli I, Razzetti R, Bongrani S. Comparative efficacy of a DA2/α2 agonist and a β-blocker in reducing adrenergic drive and cardiac fibrosis in an experimental model of left ventricular dysfunction after coronary artery occlusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;31:601–608. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199804000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenen FHH. Brain mechanisms contributing to sympathetic hyperactivity and heart failure. Circ Res. 2007;101:221–223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenen FHH, Skarda V, Yuan B, White R. Changes in cardiac ANG II postmyocardial infarction in rats: effects of nephrectomy and ACE inhibitors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H317–H325. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin SE, Katz SE, Morgan JP, Douglas PS. Effects of propranolol treatment on left ventricular function and intracellular calcium regulation in rats with postinfarction heart failure. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Gao L, Roy SK, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Neuronal angiotensin II type 1 receptor upregulation in heart failure: activation of activator protein 1 and Jun N-terminal kinase. Circ Res. 2006;99:1004–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000247066.19878.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maczewski M, Mackiewicz U. Effect of metoprolol and ivabradine on left ventricular remodelling and Ca2+ handling in the post-infarction rat heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:42–51. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Davern PJ, Giles ME, Allen AM, Badoer E, McKinley MJ. Efferent neural projections of angiotensin receptor (AT1) expressing neurones in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:139–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omerovic E, Bollano E, Soussi B, Waagstein F. Selective β1-blockade attenuates post-infarct remodelling without improvement in myocardial energy metabolism and function in rats with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:725–732. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima N, Onimaru H, Takechi H, Yamamoto K, Watanabe A, Uchida T, Nishida Y, Oda T, Kumagai H. Aldosterone is synthesized in and activates bulbospinal neurons through mineralocorticoid receptors and ENaCs in the RVLM. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:504–512. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel KP, Zhang K. Neurohumoral activation in heart failure: role of paraventricular nucleus. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:722–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Wang H, Leenen FHH. Increases in brain and cardiac AT1 receptor and ACE densities after myocardial infarct in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1665–H1671. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00858.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruyama R, Sakuraba M, Wilson LL, Wandrey NE, Armstrong WE. Epithelial Na+ sodium channels in magnocellular cells of the rat supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E273–E285. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00407.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahid-Ansari F, Leenen FHH. Pattern of neuronal activation in rats with CHF after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H2140–H2146. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez J, Adjounian MFC, Sumners C, González A, Diez-Freire C, Raizada MK. Selective silencing of angiotensin receptor subtype 1a (AT1aR) by RNA interference. Hypertension. 2005;45:115–119. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150161.78556.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Huang BS, Ganten D, Leenen FHH. Prevention of sympathetic and cardiac dysfunction after myocardial infarction in transgenic rats deficient in brain angiotensinogen. Circ Res. 2004;94:843–849. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000120864.21172.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HW, Amin MS, El-Shahat E, Huang BS, Tuana BS, Leenen FHH. Effects of central sodium on epithelial sodium channels in rat brain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299:R222–R233. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00834.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Skelley L, Cade R, Sun Z. AAV delivery of mineralocorticoid receptor shRNA prevents progression of cold-induced hypertension and attenuates renal damage. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1097–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Chow LT, Sanderson JE. Effect of carvedilol in comparison with metoprolol on myocardial collagen postinfarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:276–281. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00671-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Angiotensin II upregulates hypothalamic AT1 receptor expression in rats via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1425–H1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00942.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Mitogen-activated protein kinases mediate upregulation of hypothalamic angiotensin II type 1 receptors in heart failure rats. Hypertension. 2008;52:679–686. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xydas S, Kherani AR, Chang JS, Klotz S, Hay I, Mutrie CJ, Moss GW, Gu A, Schulman AR, Gao D, Hu D, Wu EX, Wei C, Oz MC, Wang J. β2-Adrenergic stimulation attenuates left ventricular remodeling, decreases apoptosis, and improves calcium homeostasis in a rodent model of ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:553–561. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.099432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Wei SG, Zhang ZH, Gomez-Sanchez E, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Does aldosterone upregulate the brain renin-angiotensin system in rats with heart failure. Hypertension. 2008;51:727–733. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Wei SG, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ regulates inflammation and renin-angiotensin system activity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and ameliorates peripheral manifestations of heart failure. Hypertension. 2012;59:477–484. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZH, Francis J, Weiss RM, Felder RB. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system excites hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H423–H433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00685.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Li YF, Wang W, Patel KP. Enhanced angiotensin-mediated excitation of renal sympathetic nerve activity within the paraventricular nucleus of anesthetized rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1364–R1374. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00149.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]