Summary

We reported here that the regioisomeric O 2-, N3- and O 4-ethylthymidine exert distinct effects on DNA replication in E.coli cells, with the O 2 and N3 lesions being highly blocking to DNA replication and all three lesions being highly mutagenic.

Abstract

Exposure to environmental agents and endogenous metabolism can both give rise to DNA alkylation. Thymine is known to be alkylated at O 2, N3 and O 4 positions; however, it remains poorly explored how the regioisomeric alkylated thymidine lesions compromise the flow of genetic information by perturbing DNA replication in cells. Herein, we assessed the differential recognition of the regioisomeric O 2-, N3- and O 4-ethylthymidine (O 2-, N3- and O 4-EtdT) by the DNA replication machinery of Escherichia coli cells. We found that O 4-EtdT did not inhibit appreciably DNA replication, whereas O 2- and N3-EtdT were strongly blocking to DNA replication. In addition, O 4-EtdT induced a very high frequency of T→C mutation, whereas nucleotide incorporation opposite O 2- and N3-EtdT was promiscuous. Replication experiments with the use of polymerase-deficient cells revealed that Pol V constituted the major polymerase for the mutagenic bypass of all three EtdT lesions, though Pol IV also contributed to the T→G mutation induced by O 2- and N3-EtdT. The distinct cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of the three regioisomeric lesions could be attributed to their unique chemical properties.

Introduction

Human cells are constantly exposed to a variety of endogenous and exogenous agents that can induce damage to genomic DNA (1). Unrepaired DNA lesions may block DNA replication and induce mutations, which may ultimately result in the development of cancer and other human diseases (1).

Alkylation represents a major type of DNA damage (2), where ethylation on the N7 and O 6 of guanine, N3 of adenine, as well as the O 2, N3 and O 4 of thymine is known to occur in DNA of mammalian cells and tissues (3–8). In particular, a recent study revealed that O 2-, N3- and O 4-ethylthymidine (O 2-, N3- and O 4-EtdT) could be detected in leukocyte DNA of smokers at the levels of four to five lesions per 107 nucleosides, which are ~1–2 orders of magnitude higher than those in leukocyte DNA of non-smokers (9). This is in keeping with the previous findings that ethylating agent(s) are present in tobacco and its smoke (3,6,8,9). Although N7-ethylguanine, N3-ethyladenine and O 6-ethylguanine can be efficiently repaired, O 4- and O 2-alkylthymidine derivatives are known to be poor substrates for DNA repair enzymes and persist in mammalian tissues (3,4,10). Several studies have also been conducted about the repair of the O-alkylated thymine derivatives by Escherichia coli DNA repair proteins (11), where O 2-methylthymine was found to be a substrate for AlkA in vitro (12) and O 4-methylthymine could be repaired by Ada and Ogt at efficiencies that are similar to or better than O 6-methylguanine (13,14). Not much is known about the repair of N3-EtdT, except that its structurely related N3-methylthymidine (N3-MedT) was found to be a poor substrate for E.coli AlkB (15).

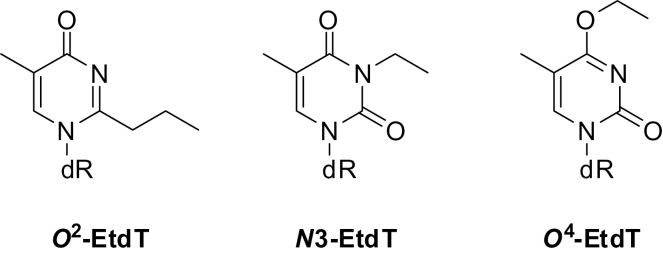

Understanding the biological consequences of DNA damage, particularly its effects on carcinogenesis, necessitates the investigation about how DNA lesions compromise the fidelity and efficiency of DNA replication. In this context, multiple studies have shown that O 4-EtdT is a highly mutagenic lesion (16–18); no studies, however, have been conducted to examine how site specifically incorporated N3-EtdT and O 2-EtdT inhibit DNA replication and induce mutations in cells. Herein, we set out to examine how the regioisomeric O 2-, N3- and O 4-EtdT lesions (Scheme 1) are differentially recognized by the entire replication apparatus of E. coli cells.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structures of the three EtdT lesions. ‘dR’ designates 2-deoxyribose.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals, unless otherwise specified, were from Sigma–Aldrich (St Louis, MO) or EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol was obtained from TCI America (Portland, OR). All unmodified oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODNs) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), and the 12mer ODNs harboring a site specifically incorporated O 2-EtdT, N3-EtdT or O 4-EtdT were previously synthesized (19). Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was purchased from USB Corporation (Cleveland, OH), and all other enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). [γ-32P]ATP was obtained from Perkin Elmer (Piscataway, NJ).

M13mp7(L2) plasmid and wild-type AB1157 E. coli strains were kindly provided by Prof. John M.Essigmann, and polymerase-deficient AB1157 strains [Δpol B1::spec (pol II-deficient), ΔdinB (pol IV-deficient), ΔumuC::kan (pol V-deficient), ΔumuC::kan ΔdinB (pol IV, pol V-double knockout) and Δpol B1::spec ΔdinB ΔumuC::kan (Pol II, pol IV, pol V-triple knockout)] were generously provided by Prof. Graham C.Walker.

Preparation of the lesion-carrying 22mer ODN

The 12mer EtdT-containing ODNs were 5′-phosphorylated and ligated individually with a 10mer ODN, d(AGTGGAAGAC), in the presence of a template in the ligation buffer with T4 DNA ligase and ATP at 16°C for 8h. The resulting 22mer ODN was purified by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

Construction of single-stranded lesion-containing and lesion-free competitor M13 genomes

The lesion-containing and lesion-free M13mp7(L2) genomes were prepared according to the previously reported procedures (20). First, 20 pmol of single-stranded (ss) M13 genome was digested with 40U EcoRI at 23°C for 8h to linearize the vector. The resulting linearized vector was mixed with two scaffolds, d(CTTC CAC TC ACTG AATCA TGGTC ATA GCTTTC) and d(AAAAC GACGGC CAGTGAATTATAGC) (25 pmol), each spanning one end of the linearized vector. To the mixture, 30 pmol of the 5′-phosphorylated 22mer EtdT-bearing ODNs or the competitor ODN [25mer, d(GCAGGAT GTCATGG CGA TAAGCTAT)] was subsequently added, and the DNA was annealed. The resulting mixture was treated with T4 DNA ligase at 16°C for 8h. T4 DNA polymerase (22.5U) was subsequently added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 4h to degrade the excess scaffolds and the unligated vector. The lesion-containing and the lesion-free M13 genomes were purified from the solution by using Cycle Pure Kit (Omega, Norcross, GA). The constructed lesion-containing genomes were normalized against the lesion-free competitor genome following published procedures (20).

Transfection of lesion-containing and competitor M13 genomes into E.coli cells

The N3-EtdT-, O 2-EtdT- or O 4-EtdT-containing M13 genomes and the corresponding dT-containing control genome were mixed with 25fmol of the competitor genome at molar ratios of 20:1, 20:1 and 1:1, respectively. The mixtures were transfected into SOS-induced, electrocompetent wild-type AB1157 E. coli cells and the isogenic E. coli cells that are deficient in pol II, pol IV, pol V, or all three polymerases, following the previously published procedures (20). The E. coli cells were grown in Luria–Bertani broth at 37°C for 6h after transfection. The phage was recovered from the supernatant through centrifugation of medium at 13 000 r.p.m. for 5min. The phage was further amplified in SCS110 E. coli cells to increase the progeny/lesion-genome ratio. The amplified phage was finally purified using the QIAprep Spin M13 kit (Qiagen) to obtain the ssM13 DNA template for PCR amplification.

Quantification of bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies

We employed the competitive replication and adduct bypass assay developed by Delaney et al. (20) to assess the bypass efficiencies of N3-EtdT, O 2-EtdT and O 4-EtdT in vivo (Supplementary Figure S1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The PCR amplification was carried out with the use of Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase for the sequence region of interest in the ssM13 DNA template. The primers were d(YCAGC TAT GACCATGATT CAGT GAGTGGA) and d(YTCG GTGCGGGC CTCTT CGCTATTAC) (Y is an amino group). The amplification cycles were 30, each cycle consisting of 10 s at 98°C, 30 s at 65°C and 15 s at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 5min. The PCR products were purified by using Cycle Pure Kit. For the determination of bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies, a portion of the above PCR products was digested with 10U BbsI and 1U shrimp alkaline phosphatase in 10 µl New England Biolabs buffer 4 at 37°C for 30min, followed by heating at 80°C for 20min to deactivate the shrimp alkaline phosphatase. To the above mixture, 5mM dithiothreitol, 1 µM ATP (premixed with 1.66 pmol [γ-32P]ATP) and 10U T4 polynucleotide kinase in a 15 µl solution were added subsequently and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30min, followed by heating at 65°C for 20min to deactivate the T4 polynucleotide kinase. To the resulting solution, 10U MluCI was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30min, followed by quenching with 15 µl formamide gel loading buffer containing xylene cyanol FF and bromophenol blue dyes. The mixture was loaded onto 30% native polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide:bis-acrylamide = 19:1). The DNA bands were quantified by using a Typhoon 9410 variable mode imager.

After the above restriction digestion, we could obtain a short duplex, d(p*GGCGMGCTAT)/d(AATTATAGCN), in which ‘M’ represents the nucleobase incorporated at the original lesion site during DNA replication in vivo, ‘N’ is the complementary base of ‘M’ in the opposite strand, and ‘p*’ designates the [5′-32P]-labeled phosphate. The bypass efficiency was determined by using the following formula:

The mutation frequencies were determined following our previously published procedures (21). With the use of 30% native PAGE, we were able to resolve [5′-32P]-labeled d(p*GGCGTGCTAT) (non-mutagenic product, 10mer-T, Figure 2b) from the corresponding T→A and T→G mutagenic products, i.e. d(p*GGCGAGCTAT) (10mer-A) and d(p*GGCGGGCTAT) (10mer-G, Figure 2b). However, the non-mutagenic product co-migrated with the corresponding product carrying a T→C mutation at the lesion site, i.e. d(p*GGCGCGCTAT) (Figure 2b). To determine the frequency for the T→C mutation, we reversed the order of the two restriction enzyme digestion so that the bottom strand, namely, d(AATTATAGCN), is selectively [5′-32P] labeled. By doing so, we were able to completely resolve the product arising from T→C mutation at the lesion site, i.e. d(AATTATAGCG) (10mer-G), from the non-mutagenic (10mer-A) and other mutagenic products (Figure 2c). Thus, by monitoring independently the products from the two strands, we were able to quantify the frequencies for all single-base substitutions.

Identification of mutagenic products by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

The PCR products were digested with 50U BbsI and 20U shrimp alkaline phosphatase in 250 µl New England Biolabs buffer 4 at 37°C for 2h, followed by deactivating the phosphatase via heating at 80°C for 20min. To the mixture, 50U of MluCI was added, and the solution was incubated at 37°C for 1h. The resulting solution was extracted once with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol). The aqueous layer was subsequently dried in a Speed-vac, desalted with high-performance liquid chromatography and dissolved in 20 µl water. A 10 µl aliquot was injected for liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis using an Agilent Zorbax SB-C18 column (0.5×250mm, 5 µm in particle size). The gradient for LC–MS/MS analysis was 5min of 5–20% methanol followed by 35min of 20–50% methanol in 400mM 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol. The temperature for the ion-transport tube was maintained at 300°C. The LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) was set up for monitoring the fragmentation of the [M-3H]3 − ions of the 10mer [d(GGCGMGCTAT), where ‘M’ represents A, T, C or G], and d(AATTATAGCN), with ‘N’ being A, T, C or G. The fragment ions detected in the MS/MS were assigned manually (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Results and discussion

We employed a modified version of the competitive replication and adduct bypass as well as restriction endonuclease and post-labeling assays (15,21–24) for assessing how the regioisomeric O 2-EtdT, N3-EtdT or O 4-EtdT perturb DNA replication in E. coli cells. To this end, we ligated ODNs harboring a site specifically inserted O 2-EtdT, N3-EtdT or O 4-EtdT (19) into single-stranded M13 plasmid, allowed the lesion-carrying plasmid to replicate together with a lesion-free competitor plasmid in AB1157 E. coli cells and isolated the progeny plasmids. We subsequently amplified a region of the plasmid containing the initial damage site using PCR, digested the resulting PCR product with restriction enzymes and subjected the digestion mixture to LC–MS/MS and PAGE analyses (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figures S1–S5, available at Carcinogenesis Online). It is of note that flanking sequences are known to affect the mutagenic properties of DNA lesions (24,25); because our major objective is to examine the differences of the three regioisomeric EtdT lesions in compromising DNA replication, we did not assess the impact of flanking sequences on the accuracy and efficiency of DNA replication in the present study.

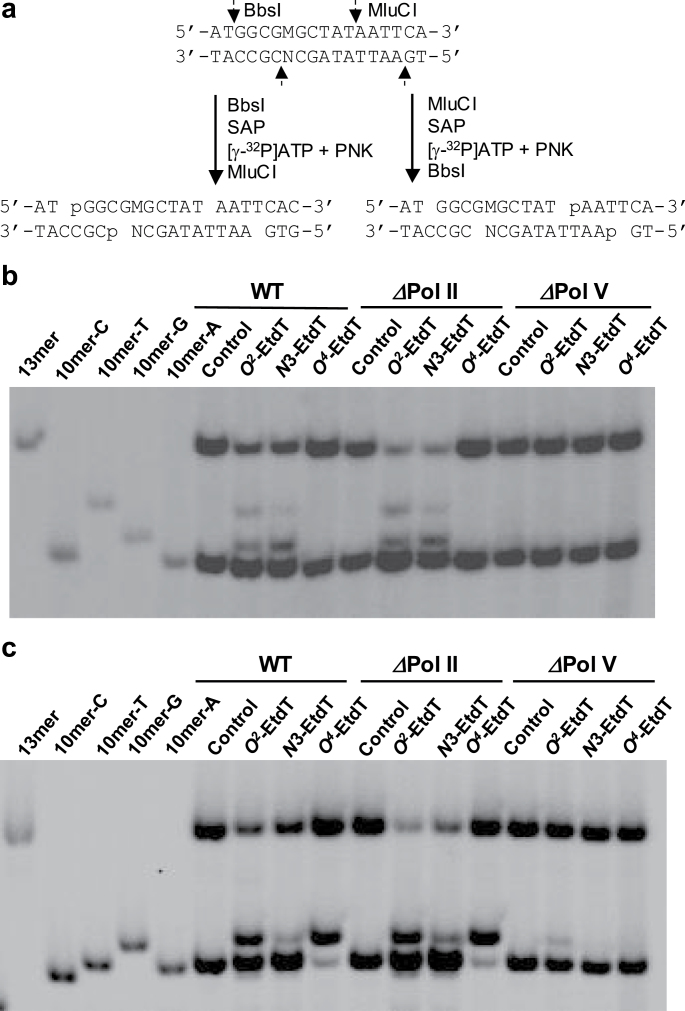

Fig. 1.

Restriction digestion and post-labeling assay for the identification and quantification of restriction fragments of PCR products arising from replication of O 2-, N3- and O 4-EtdT-containing single-stranded M13 in E. coli cells. (a) Restriction digestion and selective [5′-32P] labeling of the strand where damage was initially situated or its complementary strand. ‘M’ and ‘N’ designate the nucleobase incorporated at the lesion site and opposite base in the complementary strand, respectively. Only partial sequences for the PCR products are shown, and the PCR product for the progeny of the competitor genome is not displayed. (b and c) Native PAGE (30%) gel image for monitoring the radiolabeled fragments of PCR products for the progeny genome arising from replication of O 2-, N3- and O 4-EtdT-bearing plasmids in SOS-induced wild-type, Pol II-deficient and Pol V-deficient AB1157 cells, where the products formed from the damage-containing strand, i.e. 5′-32P-labeled d(GGCGMGCTAT) (b), and the complementary strand, i.e. 5′-32P-labeled d(AATTATAGCN) (c) were monitored. The corresponding gel images for the samples from Pol IV-deficient and triple knockout cells are shown in Supplementary Figure S5, available at Carcinogenesis Online. ‘M’ and ‘N’ designate A, T, C or G. The damage-containing strand with T→G (10mer-G) or T→A (10mer-A) mutations could be clearly resolved from each other and from that with T→C mutation (10mer-C) or without mutation (10mer-T), whereas the latter two could not be resolved from each other. The radiolabeled complementary strand with T→C mutation (10mer-G), however, could be readily resolved from that carrying no mutation (10mer-A) or T→A (10mer-T) and T→G (10mer-C) mutations. The identities for all mutagenic products were also validated by MS and MS/MS analyses (Supplementary Figures S2–S4, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

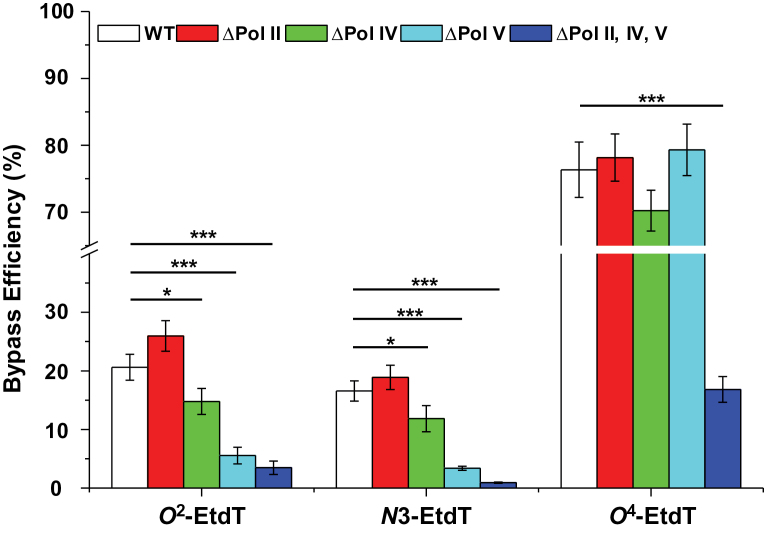

The LC–MS/MS and PAGE analysis results facilitated the identification and quantification of replication products from the damage-containing and lesion-free competitor plasmids, which enabled the calculation of the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies for the three EtdT derivatives in E. coli cells. Quantification results showed that the three regioisomers displayed substantial differences in affecting the efficiency and fidelity of DNA replication in E. coli cells. In wild-type AB1157 background under SOS induction conditions, O 4-EtdT is bypassed at ~76% efficiency relative to unmodified dT; however, N3- and O 2-EtdT exhibit strong blockage to DNA replication, with the bypass efficiencies being 21 and 17%, respectively. The marked blocking effects on DNA replication conferred by N3- and O 2-EtdT are in keeping with the previous findings that the structurely related N3-MedT and O 2-MedT are strongly cytotoxic lesions (15,26).

To examine the roles of individual SOS-induced DNA polymerases in bypassing these lesions, we performed the replication experiments in the isogenic AB1157 background with deficiencies in Pol II, Pol IV, Pol V, or all three polymerases. Our results revealed that deletion of any of the three polymerases alone did not convey a significant decline in the bypass efficiency for O 4-EtdT (Figure 2). In stark contrast, a marked drop in bypass efficiency (to ~17%) was observed for the triple knockout cells (Figure 2). These results suggest that Pol II, Pol IV and Pol V play somewhat redundant roles in bypassing O 4-EtdT in E. coli cells.

Fig. 2.

Bypass efficiencies of O 2-, N3- and O 4-EtdT in wild-type AB1157 cells (WT) or the isogenic cells that are deficient in Pol II, Pol IV, Pol V or all three SOS-induced DNA polymerases. The data represent the mean and standard deviation of results from three independent measurements. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. The P values were calculated using unpaired two-tailed t-test.

For N3-EtdT, we only observed a slight drop in bypass efficiency from 17% in wild-type cells to 12% in Pol IV-deficient background. Although no reduction in bypass efficiency was found for Pol II-deficient cells relative to wild-type cells, depletion of Pol V resulted in a substantial reduction in bypass efficiency for this lesion (to 3.4%, Figure 2). Further deletion of Pol II and Pol IV in the Pol V-deficient background led to an additional decline in bypass efficiency for N3-EtdT (to 0.9%, Figure 2). These results demonstrated that Pol V is the major polymerase involved in bypassing N3-EtdT. Very similar results were obtained for the bypass of O 2-EtdT, with the exception that additional depletion of Pol II and Pol IV in the Pol V-deficient background does not give rise to a significant drop in bypass efficiency (Figure 2).

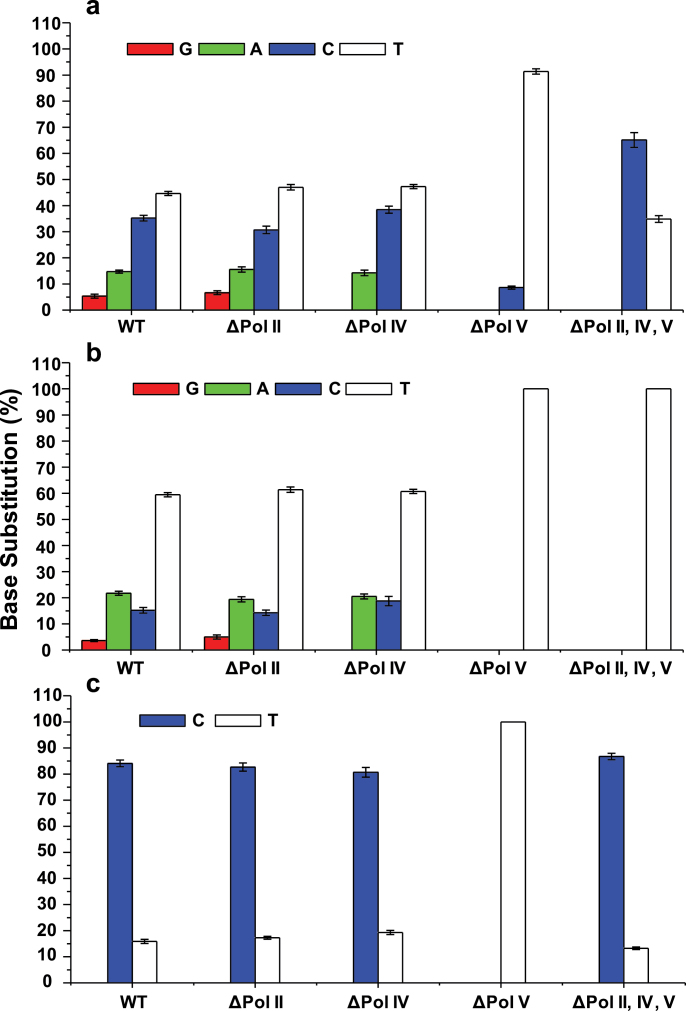

We next examined the mutagenic properties of the three regioisomeric EtdT lesions and the roles of individual SOS-induced DNA polymerases in mutation induction for these lesions (Figure 3). In wild-type AB1157 background, O 4-EtdT, N3-EtdT and O 2-EtdT led to significant frequencies (84, 15 and 35%, respectively) of T→C transition mutation. Although the depletion of Pol II or Pol IV does not lead to any significant alteration of the T→C mutation frequencies for O 4-EtdT, removal of Pol V resulted in complete abrogation of the T→C transition mutation. This result demonstrated, without ambiguity, the role of Pol V in the mutagenic bypass of O 4-EtdT in E. coli cells. Interestingly, further depletion of Pol II and Pol IV in the Pol V-null background led to T→C mutation at a similar frequency as that found for the wild-type AB1157 cells, suggesting that, in the absence of Pol V, lesion bypass mediated by Pol II and/or Pol IV is error free.

Fig. 3.

Mutagenic properties of O 2- (a), N3- (b) and O 4-EtdT (c) in SOS-induced wild-type AB1157 cells (WT) or the isogenic cells that are deficient in Pol II, Pol IV, Pol V or all three SOS-induced DNA polymerases. The data represent the mean and standard deviation of results from three independent measurements.

Different from the O 4-EtdT which leads to predominantly T→C mutation, nucleotide incorporation opposite O 2- and N3-EtdT is promiscuous, where T→A, T→C and T→G mutations were observed for O 2-EtdT at frequencies of 15, 35 and 5.4%, respectively, and for N3-EtdT at frequencies of 21, 15 and 3.1%, respectively (Figure 3). In keeping with the lack of impact of depletion of Pol II or Pol IV in the bypass efficiency for O 2- and N3-EtdT, independent removal of these two polymerases does not give rise to substantial perturbations in the mutation frequencies of these two lesions, except that the T→G mutation observed for these two lesions in wild-type cells was totally abolished in the Pol IV-deficient background (Figure 3). Consistent with the significant reduction in bypass efficiency observed for the Pol V-deficient background, we found profound alterations in mutation frequencies for O 2- and N3-EtdT when Pol V is depleted. In this scenario, we observed only a low frequency (8.6%) of T→C mutation for O 2-EtdT, and no mutagenic product was detectable for N3-EtdT (Figure 3). Nevertheless, the two lesions behave quite differently in the triple knockout background; similar as what we found for O 4-EtdT, O 2-EtdT directed significant frequency of dGMP misincorporation, as reflected by a 65% T→C mutation (Figure 3). This result suggests the relatively high fidelity of Pol II and/or Pol IV in the nucleotide incorporation opposite the lesion in cells lacking Pol V. N3-EtdT, on the other hand, directs essentially error-free nucleotide incorporation, as manifested by the failure to detect any mutagenic product for this lesion in the triple knockout background.

Exposure to ethylating agents is known to result in C:G→T:A and T:A→C:G transition mutations (27,28). Consistent with previous findings for O 4-MedT and O 4-EtdT (16–18), we found that O 4-EtdT can result in high frequencies of T→C mutation, thus supporting the role of this lesion in the T:A→C:G transition. In addition, our results demonstrate that N3- and O 2-EtdT may also make significant contributions to the ethylating agent-induced T:A→C:G transition mutation (27,28). This finding is also reminiscent of a previous biochemical study showing that N3- and O 2-EtdT could direct human DNA polymerases η and κ, which are considered orthologs of E. coli Pol V and Pol IV, respectively (29), to incorporate both dAMP and dGMP (19). Furthermore, our observation of appreciable frequency of T→G mutation for N3- and O 2-EtdT is in keeping with the previous finding that the transformation of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-modified DNA into SOS-induced E. coli cells could be processed to yield A:T→C:G transversion at a similar frequency as G:C→A:T transition (30). Along this line, it is important to note that minor-groove O 2-EtdT is known to be more efficiently induced than O 4-EtdT (27,31), and minor-groove DNA lesions are known to be highly persistent in a number of experimental settings (10,32).

Together, our results demonstrated that the three regioisomeric EtdT lesions elicit distinct effects on DNA replication, with O 4-EtdT being highly mutagenic, and the other two highly blocking to DNA replication. We also found that in E. coli cells competent in translesion synthesis, O 4-EtdT directs primarily the misincorporation of dGMP, whereas nucleotide incorporation opposite O 2- and N3-EtdT is much less selective. This latter finding is consistent with previous mutagenesis studies of corresponding methylated thymidine derivatives (15,26). These observations perhaps can be attributed to the distinct chemical properties of the three regioisomeric lesions. In this vein, the addition of an alkyl group to the O 4 position of the thymine is known to promote its preferential base pairing with guanine (33). The incorporation of an ethyl group to the N3 position, on the other hand, blocks the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding face of thymine; as a result, the hydrogen-bonding property of the nucleobase can no longer be recognized during DNA replication (34). The conjugation of an ethyl group to O 2 position of thymine, however, renders the nucleobase incapable of pairing favorably with any of the canonical nucleobases (19). Thus, all four nucleotides can be incorporated opposite O 2- and N3-EtdT during DNA replication. We also observed that the three SOS-induced polymerases play redundant roles in bypassing O 4-EtdT in E. coli cells, whereas Pol V is the major polymerase involved in bypassing N3- and O 2-EtdT. Moreover, mutagenic bypass of all three EtdT lesions involves Pol V, though Pol IV also contributes to T→G mutation induced by O 2-EtdT and N3-EtdT and the three lesions are differentially recognized by Pol II and/or Pol IV in the Pol V-deficient background. Our study, therefore, provides novel insights into the different biological consequences of the poorly repaired ethylated thymidine lesions. To our knowledge, this represents the first direct comparison of the cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of the three regioisomeric EtdT lesions in cells.

It is worth noting that although the present study was conducted by using E. coli cells as hosts for replication, some of the findings made here should be extrapolatable to mammalian cells. In this vein, the translesion synthesis machinery is highly conserved during evolution (35). For instance, E. coli Pol V and its mammalian ortholog Pol η play important roles in the replicative bypass of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer as well as the oxidatively induced 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosine (cyclo-dA) and 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyguanosine (cyclo-dG) in cells (36–40). Likewise, accurate bypass of the minor-groove N 2-(1-carboxyethyl)-2′-deoxyguanosine (N 2-CEdG) requires DinB family polymerases, i.e. Pol IV in E. coli and DNA polymerase κ in mammalian cells (21,41). Nevertheless, there are also notable differences between translesion synthesis DNA polymerases in E. coli and humans. For example, polymerase ι is only present in higher eukaryotes (35), and this polymerase was also found to be important in the bypass of the above-described cyclo-dA, cyclo-dG and N 2-CEdG lesions in mammalian cells (40,41). Thus, future studies about how these DNA lesions compromise DNA replication in human cells will provide a more complete understanding of the implications of the regioisomeric EtdT lesions in carcinogenesis.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures S1–S5 can be found at http://carcin. oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01 DK082779 to Y.W.).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- LC–MS/MS

liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- ODNs

oligodeoxyribonucleotides

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

References

- 1. Friedberg E.C., et al. (2006). DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singer B., et al. (1983). Molecular Biology of Mutagens and Carcinogens. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3. Swenberg J.A., et al. (1984). O 4-ethyldeoxythymidine, but not O 6-ethyldeoxyguanosine, accumulates in hepatocyte DNA of rats exposed continuously to diethylnitrosamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 81, 1692–1695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Den Engelse L., et al. (1987). O 2- and O 4-ethylthymine and the ethylphosphotriester dTp(Et)dT are highly persistent DNA modifications in slowly dividing tissues of the ethylnitrosourea-treated rat. Carcinogenesis, 8, 751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Godschalk R., et al. (2002). Comparison of multiple DNA adduct types in tumor adjacent human lung tissue: effect of cigarette smoking. Carcinogenesis, 23, 2081–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chao M.R., et al. (2006). Quantitative determination of urinary N7-ethylguanine in smokers and non-smokers using an isotope dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry with on-line analyte enrichment. Carcinogenesis, 27, 146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen L., et al. (2007). Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry analysis of 7-ethylguanine in human liver DNA. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 20, 1498–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anna L., et al. (2011). Smoking-related O 4-ethylthymidine formation in human lung tissue and comparisons with bulky DNA adducts. Mutagenesis, 26, 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen H.J., et al. (2012). Analysis of ethylated thymidine adducts in human leukocyte DNA by stable isotope dilution nanoflow liquid chromatography-nanospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem., 84, 2521–2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Upadhyaya P., et al. (2008). Quantitation of pyridylhydroxybutyl-DNA adducts in liver and lung of F-344 rats treated with 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and enantiomers of its metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 21, 1468–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shrivastav N., et al. (2010). Chemical biology of mutagenesis and DNA repair: cellular responses to DNA alkylation. Carcinogenesis, 31, 59–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCarthy T.V., et al. (1984). Inducible repair of O-alkylated DNA pyrimidines in Escherichia coli . EMBO J., 3, 545–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paalman S.R., et al. (1997). Specificity of DNA repair methyltransferases determined by competitive inactivation with oligonucleotide substrates: evidence that Escherichia coli Ada repairs O 6-methylguanine and O 4-methylthymine with similar efficiency. Biochemistry, 36, 11118–11124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sassanfar M., et al. (1991). Relative efficiencies of the bacterial, yeast, and human DNA methyltransferases for the repair of O 6-methylguanine and O 4-methylthymine. Suggestive evidence for O 4-methylthymine repair by eukaryotic methyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem., 266, 2767–2771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Delaney J.C., et al. (2004). Mutagenesis, genotoxicity, and repair of 1-methyladenine, 3-alkylcytosines, 1-methylguanine, and 3-methylthymine in alkB Escherichia coli . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 14051–14056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Altshuler K.B., et al. (1996). Intrachromosomal probes for mutagenesis by alkylated DNA bases replicated in mammalian cells: a comparison of the mutagenicities of O 4-methylthymine and O 6-methylguanine in cells with different DNA repair backgrounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 9, 980–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klein J.C., et al. (1990). Use of shuttle vectors to study the molecular processing of defined carcinogen-induced DNA damage: mutagenicity of single O 4-ethylthymine adducts in HeLa cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 4131–4137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Klein J.C., et al. (1994). Role of nucleotide excision repair in processing of O 4-alkylthymines in human cells. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 25521–25528 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andersen N., et al. (2013). Replication across regioisomeric ethylated thymidine lesions by purified DNA polymerases. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 26, 1730–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Delaney J.C., et al. (2006). Assays for determining lesion bypass efficiency and mutagenicity of site-specific DNA lesions in vivo . Methods Enzymol., 408, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuan B., et al. (2008). Efficient and accurate bypass of N 2-(1-carboxyethyl)-2′-deoxyguanosine by DinB DNA polymerase in vitro and in vivo . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 8679–8684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hong H., et al. (2007). Formation and genotoxicity of a guanine-cytosine intrastrand cross-link lesion in vivo . Nucleic Acids Res., 35, 7118–7127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yuan B., et al. (2008). Mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of 6-thioguanine, S6-methylthioguanine, and guanine-S6-sulfonic acid. J. Biol. Chem., 283, 23665–23670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delaney J.C., et al. (1999). Context-dependent mutagenesis by DNA lesions. Chem. Biol., 6, 743–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yuan B., et al. (2010). Efficient formation of the tandem thymine glycol/8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine lesion in isolated DNA and the mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of the tandem lesions in Escherichia coli cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 23, 11–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jasti V.P., et al. (2011). Tobacco-specific nitrosamine-derived O 2-alkylthymidines are potent mutagenic lesions in SOS-induced Escherichia coli . Chem. Res. Toxicol., 24, 1833–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zielenska M., et al. (1988). Different mutational profiles induced by N-nitroso-N-ethylurea: effects of dose and error-prone DNA repair and correlations with DNA adducts. Environ. Mol. Mutagen., 11, 473–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richardson K.K., et al. (1987). DNA base changes and alkylation following in vivo exposure of Escherichia coli to N-methyl-N-nitrosourea or N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 84, 344–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee C.H., et al. (2006). Homology modeling of four Y-family, lesion-bypass DNA polymerases: the case that E. coli Pol IV and human Pol kappa are orthologs, and E. coli Pol V and human Pol eta are orthologs. J. Mol. Graph. Model., 25, 87–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eckert K.A., et al. (1989). N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea induces A:T to C:G transversion mutations as well as transition mutations in SOS-induced Escherichia coli . Carcinogenesis, 10, 2261–2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scherer E., et al. (1980). Formation by diethylnitrosamine and persistence of O 4-ethylthymidine in rat liver DNA in vivo . Cancer Lett., 10, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brent T.P., et al. (1988). Repair of O-alkylpyrimidines in mammalian cells: a present consensus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 1759–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brennan R.G., et al. (1986). Crystal structure of the promutagen O 4-methylthymidine: importance of the anti conformation of the O(4) methoxy group and possible mispairing of O 4-methylthymidine with guanine. Biochemistry, 25, 1181–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huff A.C., et al. (1987). DNA damage at thymine N-3 abolishes base-pairing capacity during DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 12843–12850 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ohmori H., et al. (2001). The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell, 8, 7–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tang M., et al. (2000). Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature, 404, 1014–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yoon J.H., et al. (2009). Highly error-free role of DNA polymerase eta in the replicative bypass of UV-induced pyrimidine dimers in mouse and human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 18219–18224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yuan B., et al. (2011). High-throughput analysis of the mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of DNA lesions by next-generation sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res., 39, 5945–5954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jasti V.P., et al. (2011). (5′S)-8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyguanosine is a strong block to replication, a potent pol V-dependent mutagenic lesion, and is inefficiently repaired in Escherichia coli . Biochemistry, 50, 3862–3865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. You C., et al. (2013). Translesion synthesis of 8,5′-cyclopurine-2′-deoxynucleosides by DNA polymerases η, ι, and ζ. J. Biol. Chem., 288, 28548–28556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yuan B., et al. (2011). The roles of DNA polymerases κ and ι in the error-free bypass of N 2-carboxyalkyl-2′-deoxyguanosine lesions in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem., 286, 17503–17511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.