Abstract

Background

The influence of the diversity of CCR5 on HIV susceptibility and disease progression has been clearly demonstrated but how the variability of this gene influences the HIV tropism is poorly understood. We investigated whether CCR5 haplotypes are associated with HIV tropism in a Caucasian population.

Methods

We evaluated 161 HIV-positive subjects in a cross-sectional study. CCR5 haplotypes were derived after genotyping nine CCR2-CCR5 polymorphisms. The HIV subtype was determined by phylogenetic analysis using the Maximum Likelihood method and viral tropism by the genotypic tropism assay (geno2pheno). Associations between CCR5 haplotypes and viral tropism were determined using logistic regression analyses. Samples from 500 blood donors were used to evaluate the representativeness of HIV-positives in terms of CCR5 haplotype distribution.

Results

The distribution of CCR5 haplotypes was similar in HIV-positive subjects and blood donors. The majority of viruses (93.8%) belonged to HIV-1 CRF06_cpx; 7.5% were X4, and the remaining were R5 tropic. X4 tropic viruses were overrepresented among people with CCR5 human haplotype E (HHE) compared to those without this haplotype (13.0% vs 1.4%; p=0.006). People possessing CCR5 HHE had eleven times increased odds (OR=11.00; 95% CI 1.38 to 87.38) of having X4 tropic viruses than those with non-HHE. After adjusting for antiretroviral therapy (ARV), neither the presence of HHE nor the use of ARV were associated with X4 tropic viruses.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that CCR5 HHE as well as ARV treatment might be associated with the presence of HIV-1 X4 tropic viruses.

Keywords: CCR5, X4 tropic viruses, intravenous drug users

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) uses chemokine receptors (cysteinecysteine receptor 5 [CCR5] and/or cysteine-X-cysteine receptor 4 [CXCR4]) as coreceptors to enter CD4 expressing cells 1. Which of these co-receptors is used is mainly determined by the amino acid sequences of the V3 loop of gp120. Accordingly, based on co-receptor usage, HIV-1 may be classified into R5 tropic (using CCR5), X4 tropic (using CXCR4), or dual/mixed tropic (using both receptors) 2. Categorization of X4 tropic viruses as syncytium-inducing (SI) and R5 as non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) is often used but in fact these features, although highly correlated, are not identical 2.

In the early stages of HIV infection R5 tropic viruses predominate, whereas X4 tropic viruses emerge with the progression of the disease 3. Consequently, studies suggest that X4 tropic viruses are associated with an increase in viral load, a decrease in CD4+ T cell counts, and rapid progression to AIDS and death 1, 3, 4.

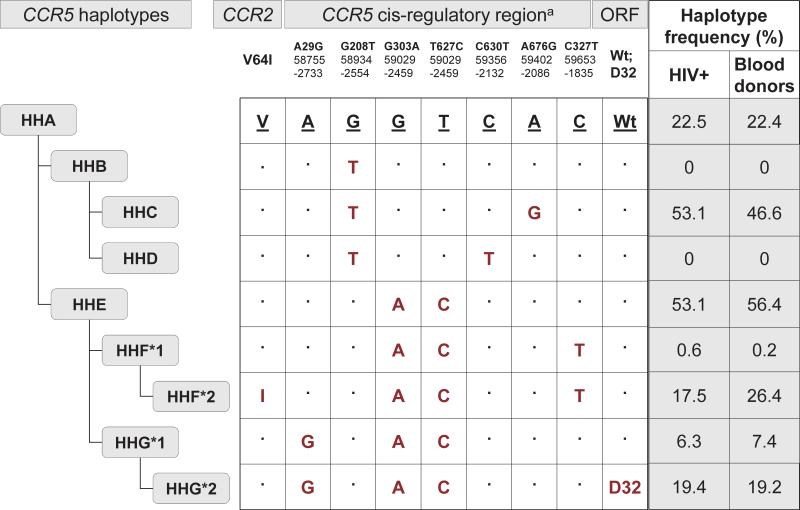

Genetic diversity in the CCR5 receptor encoding gene is associated with susceptibility to HIV infection and disease progression 5. The best described mutation, a 32 base-pair deletion (CCR5-Δ32) in the open reading frame of CCR5 in the homozygous state provides complete resistance to the acquisition of R5 tropic HIV by truncating receptor expression on the cell surface 6. In addition, there are other single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the CCR2 and CCR5 cis-regulatory region based on which the human haplotypes (HH) A-E, F*1, F*2, G*1 and G*2 have been defined using evolutionary-based analysis (Figure 1) 7, 8.

Figure 1.

CCR5 haplotypes by evolution based on CCR2 and CCR5 polymorphisms and the distribution of CCR5 haplotypes among HIV-positive subjects and blood donors. NOTE. On the basis of the linkage disequilibrium patterns between the polymorphisms in the coding (Δ32) and noncoding (promoter) region of CCR5 and the coding polymorphism (V64I) in CCR2, an evolutionary-based strategy has been used to generate the CCR5 human haplotypes (HH) shown below the CCR5 gene structure 8. These CCR5 HH are designated as HHA to HHG*2, with HHF*2 and HHG*2 denoting the haplotypes that bear the CCR2-64I and CCR5-Δ32 polymorphisms, respectively. Because of its similarity to the chimpanzee CCR5 sequence, the human CCR5 HHA haplotype is classified as the ancestral CCR5 haplotype 8. Nucleotide variations relative to the ancestral sequence are shown. The CCR5 numbering systems used in the literature are shown. Top numbering is based on GenBank accession numbers AF031236 and AF031237; middle numbering is based on GenBank accession number U95626; bottom numbering is the numbering system in which the first nucleotide of the CCR5 translational start site is designated as +1 and the nucleotide immediately upstream as -1 8. ORF, CCR5 open-reading frame; Wt, wild-type; D32, 32 base-pair deletion.

Some of the CCR5 haplotypes (e.g. HHE) are likely associated with the acceleration of disease progression but the exact mechanism is still largely unknown 7, 9. Possible associations between CCR5 diversity and co-receptor usage have been poorly studied. Recently, Crudeli et al demonstrated that the presence of SI viruses was associated with CCR5-Δ32 genotype (i.e. HHG*2) at the acute phase but not in the later stages of HIV infection 10. Another study has shown that CCR5 HHE/HHF*2 was associated with the presence of SI viruses 11.

Taking into consideration the importance of CCR5 diversity in the acquisition and progression of HIV infection on the one hand, and the relevance of HIV-1 tropism to disease progression and prognosis on the other, we aimed to investigate whether and how CCR5 haplotypes relate to the tropism of HIV-1 in a Caucasian population predominantly infected via intravenous drug use.

Material and methods

In a cross-sectional study, Caucasian HIV-positive volunteers (N = 161) were recruited from Estonian syringe-exchange programs and from three Estonian prisons in 2006 and 2007. Participants were screened for HIV using a fourth generation enzyme-linked immunoassay (Abbott IMx HIV-1/HIV-2 III Plus, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) and the results were confirmed by immunoblot assay (INNO LIA HIV I/II Score Westernblot (Microgen Bioproducts Ltd, Surrey, UK) in the Estonian Central HIV Reference Laboratory. In addition, blood samples (from residual blood left after routine testing) from 500 HIV-, HBV- and HCV-negative Estonian blood donors were analyzed to confirm the representativeness of HIV-positives in terms of distribution of CCR5 haplotypes.

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells using a Qiagen QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). CCR5 polymorphisms A29G, G208T, G303A, T627C, C630T, A676G, C927T and the presence of CCR5 Δ32 and CCR2-V64I (G190A) were detected by the Taqman Allelic Discrimination assay (Applied Biosystem, Carlsbad, CA, USA). An evolutionary-based classification of CCR5 polymorphisms was used to define the CCR5 haplotypes as described elsewhere (Figure 1) 7, 8.

HIV RNA was extracted from 140 μl plasma using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HIV-1 V3 region was amplified using seminested reverse transcription (RT)-PCR as described elsewhere 12. In brief, viral RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using 1x RT reaction buffer, 1 μM dNTP, 16U M-MuLV RT, 16U RNase inhibitor, and 0.4 μM antisense primer JA170 (5′-GTGATGTATTRCARTAGAAAAATTC-3′). V3 region was amplified in a first round PCR using 1x HotStart Buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM dNTP, one unit of 6:1 mixture of Taq and Pfu DNA polymerase, 0.3 μM primer JA168 (5′-ACAATGYACACATGGAATTARGCCA-3′) and 0.3 μM primer JA170. The PCR program consisted of 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 40 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 30 sec. The second round PCR was carried out in the same conditions as the first round using primers JA168 and JA169 (5′- AGAAAAATTCYCCTCYACAATTAAA-3′) and 30 cycles. All RT and PCR reagents were purchased from Fermentas (Vilnius, Lithuania). All second round PCR products were directly sequenced using the ABI Prism Big Dye 3.0 fluorescent terminator sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the second round PCR primers.

V3 sequences were assembled to contigs with the Vector NTI software (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). Alignments were conducted by MEGA 5 (www.megasoftware.net) software packages and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the General Time Reversible model 13,14. All reference sequences were taken from the Los-Alamos HIV Sequence Database (www.hiv.lanl.gov). HIV-1 tropism was determined by geno2pheno analysis (www.geno2pheno.org) by liberal criteria using a false positive rate (FPR) of 20% as suggested previously 15.

The program R 2.13.1 (www.r-project.org last accessed 1st January 2012) was used for statistical analyses. The distribution of X4 tropic virus between different CCR5 haplotypes, and between the subgroup receiving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment and the untreated subgroup were compared with Fisher's exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were constructed to determine the associations between CCR5 haplotypes, viral tropism, and ARV treatment.

The Ethics Committees of Tallinn and Tartu approved this study. All HIV-positive subjects gave informed consent to take part in the study. Blood donors agreed to the use of residual blood for research purposes.

Results

The HIV-positive population (n = 161) was characterised by the predominance of young, male, intravenous drug users (IDUs) (80%), and by the high rate of co-infection with HCV (86%) (Table 1).

The HIV-1 subtypes were determined by phylogenetic analyses which revealed the monophyletic pattern of the V3 region of HIV-1 which is consistent with our previous studies 16, 17. Of the sequenced viruses, 93.8% belonged to CRF06_cpx. Two viruses were found to be of subtype B and and four were A1, while four viruses remained unclassified (data not shown). Using the geno2pheno algorithm, 12/161 viruses (7.5%) were determined to be X4 tropic and the remaining viruses were R5 tropic.

While analysing viral tropism in terms of ARV treatment, we observed that X4 tropic viruses were overrepresented in ARV-treated compared to treatment-naive subjects [23% (3/13) vs 4.7% (6/127), respectively; p=0.038]. The ARV treatment history of three subjects with X4 tropic viruses was unknown. A univariate logistic regression model revealed associations between ARV treatment and the presence of X4 tropic viruses (odds ratio [OR] = 6.05; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.31 to 27.90; p=0.021) but no other factors (gender, age, transmission route, or duration of intravenous drug use) were associated with the occurrence of X4 tropic viruses (data not shown).

In total, 160 HIV-positive subjects and 500 blood donors were successfully genotyped for CCR2-CCR5 polymorphisms and classified into haplotypes. The most common CCR5 haplotypes were HHE and HHC, followed by HHA in HIV-positives and by HHF*2 in blood donors. No subjects were categorised as HHB or HHD (Figure 1). In total, 20 different CCR5 haplotype pairs were described. The most common pairs were combinations of HHC and HHE in HIV-positive subjects (HHC/HHE – 18.8%, HHE/HHE – 11.9% and HHC/HHC – 11.3%) and HHC/HHE (18.4%), HHE/HHE (10.8%) and HHE/HHF*2 (10.0%) in blood donors. There were no differences in the distribution of CCR5 haplotypes or haplotype pairs between HIV-positive subjects and blood donors showing the representativeness of the HIV-positive population.

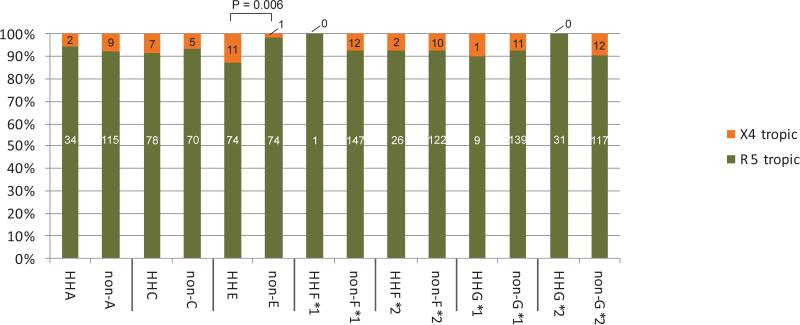

We next evaluated the distribution of X4 tropic viruses between people with different CCR5 haplotypes (Figure 2) and observed an overrepresentation of X4 tropic viruses only in those with CCR5 HHE compared with those with CCR5 non-HHE haplotypes (13.0% vs 1.4%, respectively; p=0.006). In a univariate logistic regression model people possessing CCR5 HHE had eleven times increased odds of having X4 tropic viruses compared with those with non-HHE (OR=11.00; 95% CI 1.38 to 87.38). In the multivariate model neither CCR5 HHE nor ARV treatment was associated with the presence of X4 tropic viruses (Table 2). There were no differences in the distribution of X4 tropic viruses between CCR5 haplotype pairs.

Figure 2.

The distribution of X4 and R5 tropic viruses in individuals with different CCR5 haplotypes compared to those who do not possess the particular haplotype.

Discussion

In a study predominantly involving Caucasian IDUs and looking at the associations between HIV-1 tropism and CCR5 human haplotypes we provide evidence that, together with ARV treatment, the possession of CCR5 HHE might be associated with the out-selection of X4 tropic viruses. However, neither of these factors remained independently associated in a multivariate model suggesting either an equal or combined effect of these two factors. While the associations between ARV treatment and the presence of X4 viruses (probably due to more advanced phase of infection) have been described previously 3 the role of CCR5 haplotypes in this process is much less studied.

Interestingly, both CCR5 HHE and HIV-1 X4 tropic viruses have been related to a poor outcome of HIV infection in subjects receiving ARV treatment 3, 7, 9. The CCR5 HHE has also been associated with increased susceptibility to HIV and with more rapid disease progression in European, American, Argentinian, and Japanese populations 7, 9, 18, 19. Despite of that only a limited number of studies have explored the relationships between the diversity of the CCR5 encoding gene and the prevalence of X4 tropic viruses. Crudeli et al demonstrated that people who were CCR5-δ32 heterozygotes (HHG*2) had higher rates of X4 tropic viruses than those not having this genotype in the acute phase of infection 10. Altamirano et al demonstrated that all wild type homozygotes for CCR5 SNP G303A had NSI virus while all SI variants were found in individuals with A/A or A/G genotypes (HHE-HHF*2) 11. Similarly, we have shown in this study that almost all X4 tropic viruses (11/12) occurred in individuals with CCR5 HHE, the haplotype that, among others, bears an A/A or A/G genotype at position 303 (Figure 1).

The mechanism of how X4 tropic viruses are related to disease progression in HIV infection is poorly understood 20, 21. It is still unclear whether the increased frequency of X4 tropic viruses is the cause or the consequence of disease progression. Studies have shown a switch from R5 to X4 tropic viruses in the presence of CCR5 antagonists. After the discontinuation of these agents the process is reversed – X4 tropic viruses rapidly disappeared and resided only as a minority population 22, 23. This raises the question of which viral and/or host factors control the switch from R5 to X4 tropic viruses. The present study indicates that host factors such as CCR5 haplotypes might partly explain relationships between viral tropism and HIV disease progression. We suggest that individuals with CCR5 HHE may be more likely to have X4 tropic viruses than those with other haplotypes.

As the CCR5 density correlates with viral load, disease progression, and response to treatment, it is hypothesised that X4 tropic viruses emerge as a consequence of a reduction of CCR5 expression or due to the over-expression of CXCR4 on the cell surface 24-26. The relationship between the expression of CCR5 and CXCR4 is demonstrated by the finding that CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes have lower CCR5 density and smaller numbers of cells expressing CCR5 but at the same time have an increased density of CXCR4 on CD3+ cells compared to CCR5 wild type homozygotes 27. They also showed that CCR5-Δ32 heterozygotes had lower plasma concentrations of the CXCR4 ligand, SDF-1α, suggesting an interaction between these two chemokine receptors and a possible influence on HIV tropism. Therefore, it could be presumed that changes in the expression of these receptors may have an impact on these interactions.

One could further assume that the presence of CCR5 HHE might contribute to increased CCR5 expression and, through that, to the out-selection of X4 tropic viruses. On the other hand, however, the evidence supporting this assumption is not straightforward as most studies have explored CCR5 SNPs and not the haplotypes. It has been demonstrated that haplotypes HHA-HHE are associated with higher CCR5 transcriptional activity 8, 28. Individuals who are homozygous for 303A (HHE-HHG*2) have higher CCR5 density on CD14+ monocytes and a higher number of CD4+ T cells expressing CCR5 compared to other genotypes 29, 30. More recently, Picton and co-authors (2012) in a cohort of South Africans and Caucasians failed to demonstrate any association between the presence of HHE and CCR5 expression 31. Thus, drawing conclusions on haplotypes based on SNP studies alone is difficult if not impossible.

One characteristic of our study was the high prevalence of IDUs among participants. Previous studies have shown that epithelial cells from the rectum, endocervix, and vagina produce high levels of SDF-1α, a ligand of CXCR4, which inhibits X4 tropic viruses and thus gives a preference to R5 tropic HIV acquired via sexual, but not intravenous, transmission 32. One might therefore predict that the rate of infection with X4 tropic viruses would be greater among IDUs than among those who acquired HIV sexually. The limited studies conducted thus far have given conflicting results. Spijkerman et al (1995) demonstrated a significantly lower proportion of infections with X4 viruses among IDUs compared to men who had sex with men 33. Other studies have shown the opposite result 34-36. We observed that all X4 tropic viruses were among IDUs but it was not significant. However, we noticed that IDUs clearly dominated over sexually infected subjects and we observed a lower rate of infection with X4 viruses (7.5%) than in other studies (36% to 53%) 34-36.

Some limitations of the study should be noted. First, the stage of HIV disease, the time from HIV diagnosis, the type and the length of ARV treatment, and the viral load and CD4+ counts were not collected. This prevented us from correlating the prevalence of X4 viruses with the indices of disease progression. Second, details of ARV treatment history were not reported in 13% of the study population, which may have decreased the number of X4 tropic viruses in analyses where all co-variates (tropism, ARV history and CCR5 haplotypes) were included. Another critical point was the choice of tropism assay. As in other studies, phenotypic assays could not be used because of their high costs and complex logistics. Therefore we selected a geno2pheno assay as recommended by the European guidelines for clinical HIV-1 tropism testing 37. However, we acknowledge that most genotypic assays are developed in subtype B viruses rather than CRFs; the latter constituted more than 90% of the viruses in our study. Despite this, we believe that these limitations do not prevent us from drawing reasonably firm conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated that the possession of CCR5 HHE as well as ARV treatment could be related to the presence of X4 tropic viruses in Caucasian HIV-positive subjects. However, we wish to stress that neither of these factors was independently related and the pathogenetic mechanism remains to be elucidated in futher studies. Nevetheless, we have demonstrated the influence of host genetics on the virus-host interaction during HIV infection, and suggest that differences in viral tropism could be at least partly explained by human genetic factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and the teams from Tartu Prison, from non-governmental organizations “Convictus” and “Me aitame sind” for participation in the study.

The work was supported by: European Union through the European Regional Development Fund; Estonian Science Foundation (grants 8415 and 8856); Basic Financing and the Target Financing of Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (SF0180004s12 and SF0180026s09); European Commission funded project Expanding Network for Comprehensive and Coordinated Action on HIV/AIDS prevention among IDUs and Bridging Population Nr. 2005305 (ENCAP); Global Fund to Fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria Program “Scaling up the response to HIV in Estonia” for 2003–2007; National HIV/AIDS Strategy for 2006–2015; US Civilian Research Development Foundation (grant ESX0-2722-TA-06); US National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01DA03574); the Archimedes Foundation and Norwegian Financial Mechanism/EEA(grant EE0016); the Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for AIDS and HIV Infection and VA Center for Personalized Medicine of the South Texas Veterans Health Care System, a National Institutes of Health MERIT grant (R37AI046326), and the Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award to S.K.A. S.K.A. is also supported by a VA MERIT award, the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, the Burroughs Welcome Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research and the Senior Scholar Award from the Max and Minnie Tomerlin Voelcker Fund.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Some of the data in this article were presented in an oral presentation at the 10th European Meeting on HIV & Hepatitis – Treatment Strategies & Antiviral Drug Resistance, 28-30 March, 2010, Barcelona, Spain

References

- 1.Berger EA, Murphy PM, Farber JM. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger EA, Doms RW, Fenyo EM, et al. A new classification for HIV-1. Nature. 1998 Jan 15;391(6664):240. doi: 10.1038/34571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verhofstede C, Nijhuis M, Vandekerckhove L. Correlation of coreceptor usage and disease progression. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012 Sep;7(5):432–439. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328356f6f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu XF, Wang Z, Vlahov D, Markham RB, Farzadegan H, Margolick JB. Infection with dual-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants associated with rapid total T cell decline and disease progression in injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 1998 Aug;178(2):388–396. doi: 10.1086/515646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guergnon J, Combadiere C. Role of chemokines polymorphisms in diseases. Immunol Lett. 2012 Jul 30;145(1-2):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz BJ, et al. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996 Aug 22;382(6593):722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez E, Bamshad M, Sato N, et al. Race-specific HIV-1 disease-modifying effects associated with CCR5 haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Oct 12;96(21):12004–12009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mummidi S, Bamshad M, Ahuja SS, et al. Evolution of human and non-human primate CC chemokine receptor 5 gene and mRNA. Potential roles for haplotype and mRNA diversity, differential haplotype-specific transcriptional activity, and altered transcription factor binding to polymorphic nucleotides in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J Biol Chem. 2000 Jun 23;275(25):18946–18961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000169200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangano A, Gonzalez E, Dhanda R, et al. Concordance between the CC chemokine receptor 5 genetic determinants that alter risks of transmission and disease progression in children exposed perinatally to human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 2001 Jun 1;183(11):1574–1585. doi: 10.1086/320705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crudeli CM, Aulicino PC, Rocco CA, Bologna R, Mangano A, Sen L. Relevance of early detection of HIV type 1 SI/CXCR4-using viruses in vertically infected children. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 Jul;28(7):685–692. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altamirano A, Crudeli C, Catano G, et al. Host genetic factors that influence the prevalence of HIV-1 syncytium inducing (SI) variants during pediatric primary infection. 18th Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leitner T, Korovina G, Marquina S, Smolskaya T, Albert J. Molecular epidemiology and MT-2 cell tropism of Russian HIV type 1 variant. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996 Nov 20;12(17):1595–1603. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011 Oct;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter H, Eberle J, Müller H, et al. Empfehlungen zur Bestimmung des HIV-1-Korezeptor-Gebrauchs. 2012 http://www.daignet.de/site-content/hiv-therapie/leitlinien-1/Leitlinien%20zur%20Topismus_Testung%20Stand%20Juni%202009.pdf.

- 16.Avi R, Huik K, Sadam M, et al. Absence of genotypic drug resistance and presence of several naturally occurring polymorphisms of human immunodeficiency virus-1 CRF06_cpx in treatment-naive patients in Estonia. J Med Virol. 2009 Jun;81(6):953–958. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avi R, Huik K, Sadam M, et al. Characterization of integrase region polymorphisms in HIV type 1 CRF06_cpx viruses in treatment-naive patients in Estonia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 Oct;26(10):1109–1113. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, Song R, Masciotra S, et al. Association of CCR5 human haplogroup E with rapid HIV type 1 disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005 Feb;21(2):111–115. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen L, Li M, Chaowanachan T, et al. CCR5 promoter human haplogroups associated with HIV-1 disease progression in Thai injection drug users. Aids. 2004 Jun 18;18(9):1327–1333. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamlyn E, Hickling S, Porter K, et al. Increased levels of CD4 T-cell activation in individuals with CXCR4 using viruses in primary HIV-1 infection. Aids. 2012 Apr 24;26(7):887–890. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351e721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoddart CA, Keir ME, McCune JM. IFN-alpha-induced upregulation of CCR5 leads to expanded HIV tropism in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Feb;6(2):e1000766. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGovern RA, Thielen A, Mo T, et al. Population-based V3 genotypic tropism assay: a retrospective analysis using screening samples from the A4001029 and MOTIVATE studies. Aids. 2011 Oct 23;24(16):2517–2525. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e6cfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsibris AM, Korber B, Arnaout R, et al. Quantitative deep sequencing reveals dynamic HIV-1 escape and large population shifts during CCR5 antagonist therapy in vivo. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiser AL, Vincent T, Brieu N, et al. High CD4(+) T-cell surface CXCR4 density as a risk factor for R5 to X4 switch in the course of HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Dec 15;55(5):529–535. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f25bab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gervaix A, Nicolas J, Portales P, et al. Response to treatment and disease progression linked to CD4+ T cell surface CC chemokine receptor 5 density in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vertical infection. J Infect Dis. 2002 Apr 15;185(8):1055–1061. doi: 10.1086/339802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynes J, Portales P, Segondy M, et al. CD4 T cell surface CCR5 density as a host factor in HIV-1 disease progression. Aids. 2001 Sep 7;15(13):1627–1634. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shalekoff S, Tiemessen CT. CCR5 delta32 heterozygosity is associated with an increase in CXCR4 cell surface expression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003 Jun;19(6):531–533. doi: 10.1089/088922203766774595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDermott DH, Zimmerman PA, Guignard F, Kleeberger CA, Leitman SF, Murphy PM. CCR5 promoter polymorphism and HIV-1 disease progression. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). Lancet. 1998 Sep 12;352(9131):866–870. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salkowitz JR, Bruse SE, Meyerson H, et al. CCR5 promoter polymorphism determines macrophage CCR5 density and magnitude of HIV-1 propagation in vitro. Clin Immunol. 2003 Sep;108(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shieh B, Liau YE, Hsieh PS, Yan YP, Wang ST, Li C. Influence of nucleotide polymorphisms in the CCR2 gene and the CCR5 promoter on the expression of cell surface CCR5 and CXCR4. Int Immunol. 2000 Sep;12(9):1311–1318. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.9.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picton AC, Paximadis M, Tiemessen CT. CCR5 promoter haplotypes differentially influence CCR5 expression on natural killer and T cell subsets in ethnically divergent HIV-1 uninfected South African populations. Immunogenetics. 2012 Nov;64(11):795–806. doi: 10.1007/s00251-012-0642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agace WW, Amara A, Roberts AI, et al. Constitutive expression of stromal derived factor-1 by mucosal epithelia and its role in HIV transmission and propagation. Curr Biol. 2000 Mar 23;10(6):325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spijkerman IJ, Koot M, Prins M, et al. Lower prevalence and incidence of HIV-1 syncytium-inducing phenotype among injecting drug users compared with homosexual men. Aids. 1995 Sep;9(9):1085–1092. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brumme ZL, Goodrich J, Mayer HB, et al. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of CXCR4-using HIV-1 in a large population of antiretroviral-naive individuals. J Infect Dis. 2005 Aug 1;192(3):466–474. doi: 10.1086/431519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Mendoza C, Rodriguez C, Garcia F, et al. Prevalence of X4 tropic viruses in patients recently infected with HIV-1 and lack of association with transmission of drug resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007 Apr;59(4):698–704. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monno L, Scudeller L, Ladisa N, Maggi P, Angarano G. A greater prevalence of X4 viruses in HIV type 1 intravenous drug users reflects a “CD4+ effect”. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011 Oct;27(10):1029–1031. doi: 10.1089/AID.2010.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandekerckhove LP, Wensing AM, Kaiser R, et al. European guidelines on the clinical management of HIV-1 tropism testing. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 May;11(5):394–407. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.