Abstract

Two new cyclopeptides, mullinamides A [cyclo-(-l-Gly-l-Glu-l-Val-l-Ile-l-Pro-)] and B [cyclo-(-l-Glu-l-Met-l-Pro-)] were isolated from the crude extract of terrestrial Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46 along with the three known cyclopeptides surugamide A [cyclo-(-l-Ile-d-Ile-l-Lys-l-Ile-d-Phe-d-Leu-l-Ile-d-Ala-)], cyclo-(-l-Pro-l-Phe-) and cyclo-(-l-Pro-l-Leu-). The structures of the new compounds were elucidated by the cumulative analyses of NMR spectroscopy and high resolution mass spectrometry. While mullinamides A and B displayed no appreciable antimicrobial/fungal activity or cytotoxicity, this study highlights the first reported antibacterial activity of surugamide A.

Keywords: surugamide, cyclopeptide, natural product, pharmacognosy, bioprospecting, antibiotic

INTRODUCTION

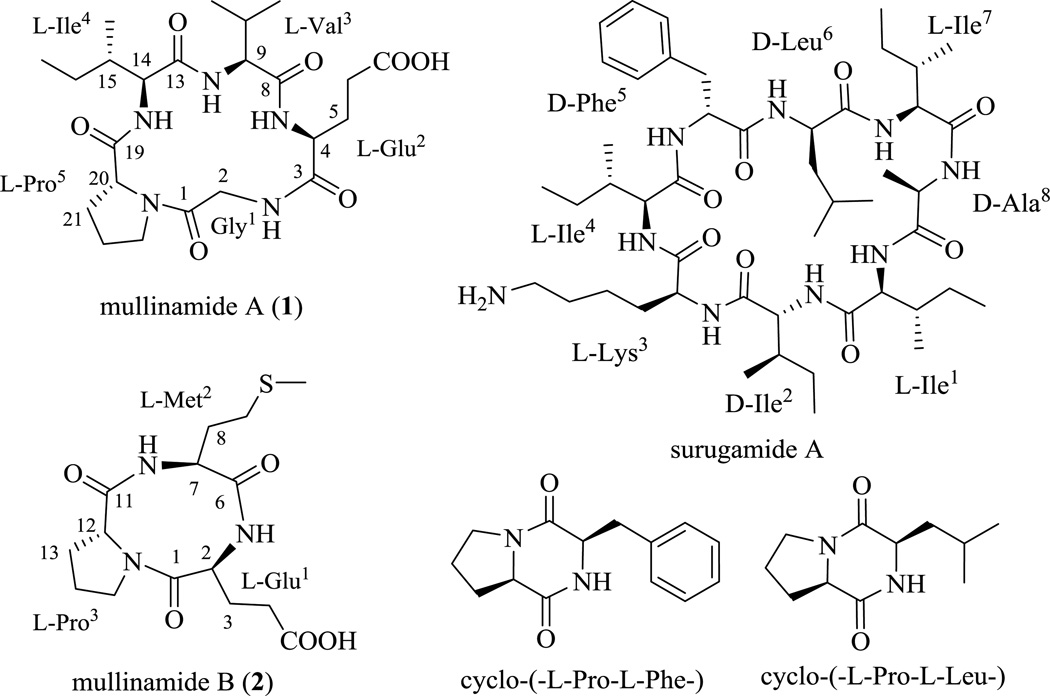

Coal fires, initiated either via natural ignition or human intervention, and can persist uncontrolled for decades in underground coal mines, coal waste piles, and unmined coal beds. They occur worldwide in all coal-bearing geographies and produce substantial greenhouse gas and toxic emissions, which, in the case of underground coal fires, are exhausted through thermal vents and seams.1–4 As such, these exhaust ports and adjacent environments offer highly unique soil/atmospheric conditions likely to impact upon the metabolic output of terrestrial actinomycetes. Within this context, we have focused upon two underground coal mine fire sites in eastern Kentucky (Ruth Mullins and Truman Shepard)5–8 and this effort has facilitated the discovery of a range of new secondary metabolites from corresponding Streptomyces strains including the recently reported unique tetracyclic polyketide ruthmycin.9–13 As an extension of this ongoing effort, herein we describe the isolation, structure elucidation and preliminary biological activity assessment of five cyclic peptides (Figure 1) from the previously unreported Ruth Mullins isolate Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46. Notably, two of the cyclic peptides, mullinamides A [cyclo-(-l-Gly-l-Glu-l-Val-l-Ile-l-Pro-)] (1) and B [cyclo-(-l-Glu-l-Met-l-Pro-)] (2), are new and a third, surugamide A, is a cyclic octapeptide recently reported as a metabolite of a marine Streptomyces isolated near Japan.14 While surugamides were previously found to weakly inhibit caspase in vitro, the current study is also the first to divulge the moderate antibacterial activity of surugamide A (Staphylococcus aureus MIC of 10 µM).

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds isolated from Streptomyces sp. RM-27–46.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

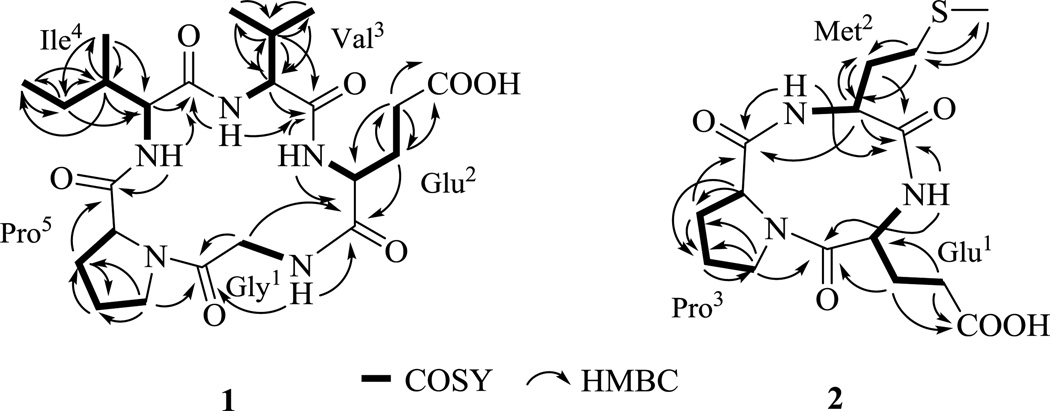

Compound 1 was obtained as white powder (Table 1). The molecular formula of 1 was established as C23H37N5O7 on the basis of HR-ESI-MS (Table 1) and NMR data, indicating eight degrees of unsaturation. The proton NMR (Table 2) of 1 in DMSO-d6 displayed typical features of a peptide-derived compound, including four amide protons at δH 8.07 (t, 5.4), 8.00 (d, 6.8), 7.87 (d, 8.7) and 7.84 (d, 8.3), and five α-protons at δH 4.42, 4.19, 4.12, 4.09, 4.00 and 3.80 ppm. The 13C-NMR of 1 (Table 2) was also consistent with a peptidic nature with six amide/acid carbonyls (δC 181.7, 175.5, 174.6 (two overlapped carbon signals), 174.0, 169.5) and five α-carbon signals (δC 61.5, 59.4, 59.0, 58.3, 42.7). The 1D (1H and 13C) and 2D (COSY, TOCSY, HSQC and HMBC) NMR data revealed that 1 was composed of five amino acid residues. Specifically, the independent spin system of the type XCHCH2CH2X' suggested the presence of a glutamic acid unit while the spin systems of XCHCH(CH3)2, XCHCH(CH3)CH2CH3 and XCHCH2CH2CH2X' identified from TOCSY experiments were indicative of valine, isoleucine, and proline residues. One remaining CH2 group, which lacked correlations with other protons in the COSY and TOCSY spectra, suggested the presence of a glycine moiety. Five carbonyl signals and the proline ring accounted for 7 of the requisite 8 degrees of unsaturation as dictated by the molecular formula, suggesting a cyclic form. Key connections among the five amino acid residues were established via HMBC correlations (Figure 2): 2-NH (δH 8.07) to C-2 (δC 42.7) and C-3 (δC 175.5); 4-NH (δH 8.00) to C-3 (δC 175.5) and C-8 (δC 174.6); 9-NH (δH 7.84) to C-8 (δC 174.6) and C-13 (δC 174.0); 14-NH (δH 7.87) to C-13 (δC 174.0) and C-19 (δC 174.6); and H-23 (δH 3.43, 3.52) to C-1 (δC 169.5). Importantly, these connections established the sequence 1 as cyclo-(-Gly-Glu-Val-Ile-Pro-). Subsequent Marfey’s analysis15 of the total hydrolysate of 1 using 6 n HCl overnight revealed the building blocks of 1 to be proteinogenic amino acids (l-Glu, l-Ile, l-Pro and l-Val). Thus, the structure of 1 was assigned as cyclo-(-l-Gly-l-Glu-l-Val-l-Ile-l-Pro-) and, as a new cyclopeptide, was named mullinamide A in reference to its point of origin.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical properties of mullinamides A (1) and B (2)

| mullinamide A (1) | mullinamide B (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Formula | C23H37N5O7 | C15H23N3O5S |

| Appearance | White powder | White powder |

| UV | End absorption | End absorption |

| [α]D25 | −36.9° (c 2.5, MeOH) | −10.6° (c 0.3, MeOH) |

| (+)-ESI-MS: m/z | 496 [M + H]+, 991 [2 M + H]+ | 358 [M + H]+, 715 [2 M + H]+ |

| (−)-ESI-MS: m/z | 494 [M − H]− | - |

| (+)-HR-ESI-MS: m/z Calcd. | 496.2767 [M + H]+, 518.2590 [M + Na]+, 496.2771 for C23H38N5O7 [M + H]+, 518.2591 for C23H37N5O7Na [M + Na]+ | 358.1434 [M + H]+, 358.1437 for C15H24N3O5S [M + H]+ |

| (−)-HR-ESI-MS: m/z Calcd | 494.2627 [M − H]− 494.2615 for C23H36N5O7[M − H]− | 356.1287 [M − H]− 356.1280 for C15H22N3O5S [M − H]− |

Table 2.

1H and 13C NMR data for mullinamides A (1) and B (2)

| Mullinamide A (1) | Mullinamide B (2) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δHa (J in Hz) | δHb (J in Hz) | δCc, type | Position | δHa (J in Hz) | δHb (J in Hz) | δCc, type | ||

| Gly | 1 | 169.5, qC | Glu | 1 | 175.3, qC | ||||

| 2a | 3.97, d (16.8) | 3.80, dd (5.8, 17.1) | 42.7, CH2 | 2 | 4.22, m | 4.05, m | 57.8, CH | ||

| 2b | 4.16, d (16.8) | 4.00, dd (4.9, 17.1) | 3 | 2.29, 2.45, m | 2.16, m | 26.7, CH2 | |||

| NH | 8.07, t (5.4) | 4 | 2.06, 2.38, m | 1.84, m | 30.9, CH2 | ||||

| Glu | 3 | 175.5, qC | 5 | 181.7, qC | |||||

| 4 | 4.22, m | 4.12, m | 58.3, CH | NH | 7.80, d (4.6) | ||||

| 5 | 2.11, 2.48, m | 2.42, m | 26.8, CH2 | Met | 6 | 175.1, qC | |||

| 6 | 2.32, 2.42, m | 2.04, 2.12, m | 30.6, CH2 | 7 | 4.81, m | 4.64, m | 51.7, CH | ||

| 7 | 181.7, qC | 8 | 1.96, 2.08, m | 1.80, m | 31.9, CH2 | ||||

| NH | 8.00, d (6.8) | 9 | 2.63, m | 2.52, m | 30.6, CH2 | ||||

| Val | 8 | 174.6, qC | 10 | 2.11, s | 2.03, s | 15.4, CH3 | |||

| 9 | 4.32, m | 4.09, m | 59.0, CH | NH | 8.28, d (6.7) | ||||

| 10 | 2.18, m | 2.01, m | 31.9, CH | Pro | 11 | 172.4, qC | |||

| 11 | 0.96d | 0.94d | 18.4, CH3 | 12 | 4.45, m | 4.24, m | 60.5, CH | ||

| 12 | 0.96d | 0.94d | 19.7, CH3 | 13 | 2.02, 2.29, m | 1.81, 2.15, m | 30.3, CH2 | ||

| NH | 7.84, d (8.3) | 14 | 2.06, m | 1.90, m | 26.0, CH2 | ||||

| Ile | 13 | 174.0, qC | 15 | 3.75, 3.87, m | 3.59, 3.68 | 48.7, CH2 | |||

| 14 | 4.25, m | 4.19, m | 59.4, CH | ||||||

| 15 | 1.86, m | 1.70, m | 38.0, CH | ||||||

| 16 | 1.20, 1.60, m | 1.06, 1.45, m | 25.8, CH2 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.90, t (7.6, 7.2) | 0.80, t (7.4) | 11.4, CH3 | ||||||

| 18 | 0.96d | 0.93d | 16.0, CH3 | ||||||

| NH | 7.87, d (8.7) | ||||||||

| Pro | 19 | 174.6, qC | |||||||

| 20 | 4.49, m | 4.42, m | 61.5, CH | ||||||

| 21 | 1.94, 2.19, m | 1.75, 1.96, m | 30.7, CH2 | ||||||

| 22 | 2.00, m | 1.86, m | 26.1, CH2 | ||||||

| 23 | 3.61, m | 3.43, 3.52, m | 47.9, CH2 | ||||||

measured in CD3OD, 400MHz,

measured in DMSO-d6, 500MHz.

measured in CD3OD, 100MHz.

overlapped.

Figure 2.

1H,1H-COSY (▬) and selected HMBC (→) correlations of mullinamides A (1) and B (2).

Compound 2 was obtained as white powder and it molecular formula was deduced as C15H23N3O5S from its HR-ESI-MS at m/z 358.1434 [M + H]+ (Calcd. 358.1437 for C15H24N3O5S [M + H]+), Table 1. The 1H NMR spectrum (Table 2) of 2 also revealed peptide features with three α-protons at δH 4.64, 4.24 and 4.05 and two amide protons at δH 8.28 and 7.80 ppm. The planar structure of 2 was similarly established by 1D and 2D NMR analysis (Figure 2) to be cyclo-(-Glu-Met-Pro-), and the absolute amino acid configurations subseqeuntly identified by the total hydrolysis of 2 using 6 n HCl, followed by Marfey’s analysis method as described for 1. Based upon the cumulative data, compound 2 was identified as cyclo-(-L-Glu-L-Met-L-Pro-), and, as a new cyclopeptide, was named mullinamide B in reference to its point of origin.

Three additional compounds were also isolated from Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46 and identified as surugamide A [cyclo-(-L-Ile-D-Ile-L-Lys-L-Ile-D-Phe-D-Leu-L-Ile-D-Ala-)],14 cyclo-(-l-Pro-l-Phe-)16,17 and cyclo-(-l-Pro-l-Leu-)17 based upon correlation of cumulative NMR and HRMS data to that reported in the literature.

Mullinamides A (1) and B (2) displayed no antibacterial (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, Salmonella enterica ATCC 10708) or antifungal (against Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 204508) activities at or below 100 µM and no cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines (A549 non-small cell lung, PC3 prostate) at or below 10 µM. In contrast, surugamide A (previously only reported to inhibit bovine cathepsin B with an IC50 of 21 µM)14 displayed moderate growth inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (MIC of 10 µM). While the biosynthetic loci encoding surugamides were previously noted to be widely distributed among marine Streptomyces species collected near Japan,14 the current study suggests surugamide production may be a much broader phenomenon than previously appreciated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General experimental procedures

Optical rotation was recorded on a Jasco DIP-370 Digital Polarimeter. All NMR data was recorded at 500 MHz or 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C with Varian Inova NMR spectrometers (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). LC-MS was conducted with a Waters 2695 LC module (Waters, Milford, MA), equipped with a micromass ZQ and a Symmetry Anal C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm; Waters, Milford, MA). HR-ESI-MS spectra were recorded on an AB SCIEX Triple TOF 5600 System (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). HPLC analyses were performed on an Agilent 1260 system equipped with a photodiode array detector (PDA) detector and a Phenomenex C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Semi-preparative HPLC separation was performed on a Varian Prostar 210 HPLC system equipped with a PDA detector 330 using a Supelco Discovery®Bio wide pore C18 column (250 × 21.2 mm, 10 µm; flow rate, 8 ml/min; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All solvents used were of ACS grade and purchased from Pharmco-AAPER (Brookfield, CT). Sephadex LH-20 (25 ~ 100 µm) was purchased from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). C18-functionalised silica gel (40 ~ 63 µm) was purchased from Material Harvest Ltd. (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Amberlite®XAD16N resin (20–60 mesh) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, United States). TLC silica gel plates (60 F254) were purchased from EMD Chemicals Inc. (Darmstadt, Germany).

Isolation of Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46

The soil sample was collected from the Ruth Mullins underground coal mine fire site, Perry County, KY (coordinates: N 37° 18.725' and W 83° 10.3335'). For strain purification, 0.5 g of soil sample was suspended in 1.0 ml of sterile water and the suspension was heated at 75 °C for 10 minutes to eliminate non-sporulating bacteria. Following serial dilution (10−1, 10−2, 10−3) of the suspension with sterile water, a 100 µl aliquot was spread on oatmeal agar (Difco™, Ref: 255210, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) and on ISP4 agar (Difco™, Ref: 277210, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) plates supplemented with nalidixic acid (75 µg/ml) and cycloheximide (50 µg/ml). A number of sporulating bacterial colonies were observed after a week of incubation at 28 °C and each colony was subsequently streaked on a M2-agar plate [glucose (4.0 g), malt extract (10.0 g), yeast extract (4.0 g), CaCO3 (1.0 g) and agar (15.0 g) were dissolved in 1 liter of demineralized water]. Individual bacterial colonies were isolated from the second generation plates. AntiBase18 comparison of HPLC−high-resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC-HRMS) profiles of the culture extracts of 46 actinomycete strains isolated from a single soil sample collected near a thermal vent associated with the Ruth Mullins underground coal mine fire indicated that one of these, Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46, was capable of unique metabolite production.

Identification of Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46

Genomic DNA was isolated from a fully grown colony using the GeneJET Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The partial 16S rRNA gene fragment was amplified using universal primers (27F, 5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′; 1492R, 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′)19 and Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and was gel-purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The amplified fragment (1,311 bp) displayed 99% identity (BLAST search) to the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Streptomyces exfoliatus strain NBRC 13475. The sequence of 16S rRNA has been deposited in the NCBI nucleotide database under accession number KF732715.

Host Fermentation and Metabolite Extraction, Isolation and Purification

Streptomyces sp. RM-27-46 was cultivated on M2-agar plates at 28 °C for 7 days. Chunks of agar with the fullygrown strain were used to inoculate five 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks, each containing 50 ml of medium A [glucose (10.0 g), yeast extract (5.0 g), soluble starch (20.0 g), peptone (5.0 g), NaCl (4.0 g), K2HPO4 (0.5 g), MgSO4·7H2O (0.5), and CaCO3 (2 g) were dissolved in 1 liter of demineralized water]. Individual cultures were grown at 28 °C with shaking (200 rpm) for 3 days and subsequently used as seed cultures for the scale-up fermentation. The seed cultures were used to inoculate 100 Erlenmeyer flasks (250 ml) each containing 100 ml of medium A. The fermentation (10 L) was continued for seven days at 28 °C with 200 rpm agitation. The obtained culture broth was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 30 minutes. The biomass (mycelium) was extracted with MeOH (3 × 500 ml) and then the recovered organics were evaporated in vacuo at 40 °C to yield 5.1 g of crude extract. The supernatant was mixed with 3% (w/v) XAD-16 resin and stired overnight, followed by filtration. The resin was washed with water (3 × 600 ml) and then extracted with MeOH until the eluant was colorless. The methanol extract was subsequently evaporated to afford 15.6 g of crude extract. Both extracts (obtained from the biomass and supernatant) revealed a similar metabolite profile based upon HPLC and TLC analysis and were therefore combined (20.7 g) prior to further isolation. The crude extract was then subjected to a silica gel column chromatography (15 × 8 cm, 250 g) eluted with a gradient of CHCl3-MeOH (100:0 ~ 0:100) to yield eight fractions, A-H. Fraction B (850 mg) was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 column followed by semi-preparative HPLC (mobile phase: 5%~35% aqueous CH3CN over 25min, 8 ml/min) to yield 24.0 mg of cyclo-(-l-Pro-l-Phe-) (retention time: 15.0 min) and 15.0 mg of cyclo-(-l-Pro-l-Leu-) (retention time: 9.1 min). Fraction D (320 mg) was first subjected to a Sephadex LH-20 column (MeOH) to obtain four sub-fractions, D-1 - D-4. Sub-fraction D-2 (102 mg) was resolved by semi-preparative HPLC (mobile phase: 10%~35% aqueous CH3CN in 25min, flow rate: 8 ml/min) to yield reginamide A (14.0 mg) (retention time: 11.4 min). Compound 2 (3 mg, retention time: 10.2 min) was isolated as white powder from the sub-fraction D-3 (52.0 mg) also via semi-preparative HPLC (mobile phase: 20~60% aqueous CH3CN over 25min, 8 ml/min). Fraction E (200 mg) was subjected to a Sephadex LH-20 column (50 × 2 cm) using methanol to elute target compounds. The major fraction obtained from the Sephadex LH-20 column was dried and then further purified using semi-preparative HPLC (mobile phase: 10%~35% aqueous CH3CN in 25min, flow rate: 8 ml/min) to yield compound 1 (25.0 mg, retention time: 11.6 min). Based upon HPLC and TLC, the remaining fractions (A, C, and F-H) and sub-fractions lacked additional metabolites of interest and were therefore excluded from further consideration.

Determination of Amino Acid Configuration

The absolute configuration of each amino acid residue was determined following Marfey’s method.15 Specifically, compounds 1 or 2 (each 1.0 mg) were hydrolyzed in 6 n HCl (1 ml) at 110°C for 14 h. After drying under nitrogen, the corresponding hydrolysate was dissolved in 2 ml of EtOAc-H2O (1:1). The aqueous layer was dried in vacuo, to which a solution of 1% Marfey’s reagent in acetone (200 µl) was subsequently added, followed by 1 M NaHCO3 (50 µl). The reaction was heated to 40°C for 1 h, cooled to room temperature, and acidified with 2 N HCl (25 µl). The reaction mixture was diluted with MeOH (0.5 ml) and analyzed by HPLC using the following gradient: 0–55 min, linear gradient from 10%–55% CH3CN in 50 mM TEAP buffer (Phenomenex C18 column, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; 1ml/min; 430 nm). Derivatized standards were prepared from the authentic d- and l-glutamic acid, valine, isoleucine, proline and methionine (50 µl of a 50 mM stock) following an identical procedure. The retention times for Marfey’s derivatives of authentic d-Glu, l-Glu, d-Val, l-Val, d-Ile, l-Ile, d-Pro, l-Pro, d-Met, l-Met were 24.7, 22.6, 36.8, 31.8, 41.2, 36.1, 28.5, 26.3, 35.0 and 30.4 min, respectively. Those for the Marfey’s derivatives of Glu, Val, Ile, Pro in the hydrolysate of 1 were 22.5 (l-Glu), 31.7 (l-Val), 36.1 (l-Ile) and 26.2 (l-Pro) min, respectively. Those of 2 were 22.6 (l-Glu), 30.3 (l-Met), 26.2 (l-Pro) min, respectively.

Cell Viability Assay

A resazurin-based cytotoxicity assay, also known as AlamarBlue assay, was used to assess the cytotoxicity of agents against the human lung non-small cell carcinoma cell line A549 and human prostate cancer cell lines PC3 where the degree of cytotoxicity was based upon residual metabolic activity as assessed via reduction of resazurin (7-hydroxy-10-oxido-phenoxazin-10-ium-3-one) to its fluorescent product resorufin. A549 and PC3 cells, purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), were grown in DMEM/F-12 Kaighn’s modification and MEM/EBSS media, respectively (Thermo scientific HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine. Cells were seeded at a density 2 × 103 cells per well onto 96-well culture plates with a clear bottom (Corning, NY, USA), incubated 24 hrs at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and were exposed to test agents for 2 days (positive controls: 1.5 mM hydrogen peroxide, 10 µg/ml actinomycin D). Resazurin (150 µM final concentration) was subsequently added to each well and the plates were shaken briefly for 10 seconds and were incubated for another 3 h at 37 °C to allow viable cells to convert resazurin into resorufin. The fluorescence intensity for resorufin was detected on a scanning microplate spectrofluorometer FLUOstar Omega (BMG LABTECH GmbH, Ortenberg, Germany) using an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm. The assay was repeated in 3 independent experimental replications. In each replication, the emission of fluorescence of resorufin values in treated cells were normalized to, and expressed as a percent of, the mean resorufin emission values of untreated control (metabolically active cells; 100%, all cells are viable).

Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity Tests

Antibacterial assay

The protocol used for the determination of MIC was based upon minor modifications of previously published protocol.20 Two bacterial strains [Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) and Salmonella enterica (ATCC 10708)] were used as model strains for the assay. Single colonies from each strain were grown in 5 ml of tryptic soy broth (BD 211825) and nutrient broth (BD 234000) media, respectively, and the cultures were allowed to grow overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. The overnight culture for each strain was diluted to OD600 0.8–1.1 and 150 µl of the diluted culture was added to each well of a sterile clear polystyrene 96-well plate (TPP, Fisher Scientific). Test agents were dissolved in DMSO, serially diluted and aliquots added to the plate-based wells (kanamycin, positive control; DMSO, vehicle control). Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h with shaking (150 rpm). Samples (final concentrations 1–60 µM) and controls were tested in triplicate. The OD600 was subsequently measured using a scanning microplate spectrofluorometer FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA). The acquired OD600 values were normalized to the negative control wells (as 100% viability). The minimal concentration of the tested sample that caused growth inhibition was recorded as the MIC.

Antifungal assay

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ATCC 204508) was used in a broth microdilution antifungal assay. The assay was performed in a 96-well plate using the CLSI (formerly NCCLS) guidelines.21 Individual colonies from an overnight plate were used to innoculate 5 ml YAPD (ATCC medium number 1069) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The overnight culture was diluted to OD600 of 0.1 using sterile YAPD and 150 µl of the diluted culture was transferred to each well of a sterile clear polystyrene 96-well plate (TPP, Fisher Scientific). Test agents were dissolved in DMSO, serially diluted and aliquots added to the plate-based wells (amphotericin B, positive control; DMSO, vehicle control). The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 16 h with shaking (200 rpm) and the OD600 was subsequently measured using a scanning microplate spectrofluorometer FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA). The acquired OD600 values were normalized to the negative control wells (as 100% viability). The minimal concentration of the tested sample that caused growth inhibition was recorded as the MIC. Samples (final concentrations 1–60 µM) and controls were tested in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000117).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information including the full spectroscopic data (NMR and mass) of mullinamides A (1) and B (2) are available on the Journal of Antibiotics website (http://www.nature.com/ja).

References

- 1.Hower JC, et al. The tiptop coal-mine fire, Kentucky: preliminary investigation of the measurement of mercury and other hazardous gases from coal-fire gas vents. Int. J. Coal. Geol. 2009;80:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Keefe JMK, et al. Old smokey coal fire, Floyd County, Kentucky: estimates of gaseous emission rates. Int. J. Coal. Geol. 2011;87:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hower JC, O’Keefe JMK, Henke KR, Bagherieh A. Time series analysis of CO emissions from an Eastern Kentucky coal fire. Int. J. Coal. Geol. 2011;88:227–231. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hower JC, O'Keefe JMK, Copley GC, Hower JM. The further adventures of Tin Man: vertical temperature gradients at the Lotts Creek coal mine fire, Perry County, Kentucky. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012;101:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Keefe JMK, et al. CO2, CO, and Hg emissions from the Truman Shepherd and Ruth Mullins coal fires, Eastern Kentucky, USA. Sci. Total. Environ. 2010;408:1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva LFO, et al. Nanominerals and ultrafine particles in sublimates from the Ruth Mullins coal fire, Perry County, Eastern Kentucky, USA. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2011;85:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva LFO, et al. Geochemistry of carbon nanotube assemblages in coal fire soot, Ruth Mullins fire, Perry County, Kentucky. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012;94:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hower JC, et al. Gaseous emissions and sublimates from the Truman Shepherd coal fire, Floyd County, Kentucky: a re-investigation following attempted mitigation of the fire. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2013;116:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, et al. Ruthmycin, a new tetracyclic polyketide from Streptomyces sp. RM-4-15. Org. Lett. 2014;16:456–459. doi: 10.1021/ol4033418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, et al. Frenolicins C–G, pyranonaphthoquinones from Streptomyces sp. RM-4-15. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1441–1447. doi: 10.1021/np400231r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaaban KA, et al. Herbimycins D-F, ansamycin analogues from Streptomyces sp. RM-7-15. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1619–1626. doi: 10.1021/np400308w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaaban KA, et al. The native production of the sesquiterpene isopterocarpolone by Streptomyces sp. RM-14-6. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013 doi: 10.1080/14786419.2013.855932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaaban KA, et al. Venturicidin C, a new 20-membered macrolide produced by Streptomyces sp. TS-2-2. J. Antibio. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takada K, et al. Surugamides A–E, cyclic octapeptides with four d-amino acid residues, from a marine Streptomyces sp.: LC–MS-aided inspection of partial hydrolysates for the distinction of d- and l-Amino acid residues in the sequence. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:6746–6750. doi: 10.1021/jo400708u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marfey P. Determination of d-amino acids. II. Use of a bifunctional reagent, 1,5-difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene. Carlsberg. Res. Commun. 1984;49:591–596. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayatilake GS, Thornton MP, Leonard AC, Grimwade JE, Baker BJ. Metabolites from an antarctic sponge-associated bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:293–296. doi: 10.1021/np960095b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong J, et al. Cyclic dipeptides in actinomycete Brevibacterium sp. associated with sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicas Selenka: isolation and identification. Acad. J. Sec. Mil. Med. Univ. 2012;33:1284–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laatsch H. AntiBase. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane DJ. In: Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 1991. pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock REW. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NCCLS. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; Approved standard M27-A2. 15 Vol. 22. National Committee on Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.