Abstract

Objectives

Compare HIV injecting and sex risk in patients being treated with methadone (MET) or buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP).

Methods

Secondary analysis from a study of liver enzyme changes in patients randomized to MET or BUP who completed 24-weeks of treatment and had 4 or more blood draws. The initial 1:1 randomization was changed to 2:1 (BUP: MET) after 18 months due to higher dropout in BUP. The Risk Behavior Survey (RBS) measured past 30-day HIV risk at baseline and weeks 12 and 24.

Results

Among 529 patients randomized to MET, 391 (74%) were completers; among 740 randomized to BUP, 340 (46%) were completers; 700 completed the RBS. There were significant reductions in injecting risk (p< 0.0008) with no differences between groups in mean number of times reported injecting heroin, speedball, other opiates, and number of injections; or percent who shared needles, did not clean shared needles with bleach, shared cookers, or engaged in front/back loading of syringes. The percent having multiple sex partners decreased equally in both groups (p<0.03). For males on BUP the sex risk composite increased; for males on MET, the sex risk decreased resulting in significant group differences over time (p<0.03). For females, there was a significant reduction in sex risk (p<0.02) with no group differences.

Conclusions

Among MET and BUP patients that remained in treatment, HIV injecting risk was equally and markedly reduced, however MET retained more patients. Sex risk was equally and significantly reduced among females in both treatment conditions, but increased for males on BUP, and decreased for males on MET.

INTRODUCTION

Research over the past 20 years has shown that methadone maintenance reduces opioid use and is an effective HIV risk reduction intervention 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. This finding has been observed when methadone patients are compared to their community counterparts who are not in treatment 9, 10, 11 and when opioid use during treatment is compared to pre- and post-treatment use 3. Further, significantly lower rates of opioid use have been observed when patients with regular methadone program attendance are compared to those with poor attendance 12, and when patients receiving minimal ancillary services are compared to those receiving more intensive services 13, 14.

Consistent with these reductions in opioid use, methadone maintenance markedly reduces opioid injection and needle sharing. This finding has been reported in cross-sectional, prospective, and retrospective designs comparing methadone patients to heroin users who are not in treatment 5, 9, 15, 16, 11, and in studies measuring changes among methadone patients during treatment 14, 17. Findings have also been reported showing significantly lower rates of injection among patients who remain in treatment when compared to patients who left treatment 10, 18.

Importantly, prior research demonstrates strong associations between participation in methadone maintenance and lower rates of HIV prevalence and incidence. For example, heroin users who remained in methadone treatment during periods of rapid HIV transmission in their local communities had a dramatically lower prevalence of infection 19, 20, 21. In both prospective and retrospective studies, the incidence of HIV infections has been associated with participation 10, 7, 12 and time receiving methadone treatment 22, 23, 7. Although none of these studies were randomized trials, the strength and consistency of the findings indicate that participation in methadone maintenance is strongly associated with protection from HIV infection and that methadone treatment reduces the risk behaviors that can spread HIV 10, 24,25, 26. This risk reduction occurs both directly via reduction of injecting behaviors, but also by facilitating adherence to antiretroviral medication and reducing the viral load among persons who are infected 27.

Buprenorphine is a Schedule III, mu-opioid partial agonist with a greater margin of safety and a less intensive withdrawal 28, 29. It is available in the U.S. as a tablet or film with 4 parts buprenorphine to one part naloxone in an attempt to reduce abuse if crushed and injected and is approved for treatment of opioid addicted individuals aged 16 and above 30, 31, 32. Like methadone, treatment with buprenorphine-naloxone appears to reduce HIV risk 33, 34 and we know of only one study that directly compared HIV risk in patients treated with buprenorphine vs. methadone. It was conducted in Baltimore and randomized 47 patients to buprenorphine and 51 to methadone. Methadone doses ranged from 60-100 mg/day; buprenorphine doses were 16-32 mg on Mondays and Wednesdays with a 50% higher dose on Fridays. HIV risk was assessed at baseline and at weeks 1, 2, 3 and 18 using the Risk Behavior Interview 35. Patients in both groups had marked and equal reduction in injecting risk but only the methadone group had consistent declines in sexual risk 36. Here, we present the results of a similar comparison of a much larger sample in a secondary analysis of data from a study conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in the Clinical Trials Network 37.

METHODS

The main study (“START”) was a randomized trial that evaluated transaminase changes in patients randomized to treatment with MET or BUP. Participants were consenting individuals who were applying for treatment at 1 of 8 methadone programs located across the United States. Eligibility criteria included being age 18 or older; meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for opioid dependence; and not having an alanine amino transferase (ALT) or aspartate amino transferase (AST) value > 5 times or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) >3 times above the upper limit of normal. Exclusion criteria included serious medical conditions that could make study participation unsafe or impractical; schizophrenia, Bipolar I disorder, homicidal or suicidal ideation, or cognitive impairment that made informed consent difficult to obtain; and poor venous access such that repeated blood samples to measure liver enzymes would be difficult to obtain. Recruitment occurred between May 2006 and October 2009 with follow-up assessments through August 2010.

The FDA requested this study based on reports of elevated liver enzymes in patients treated with BUP and required a minimum of 300 “evaluable” participants on each medication. The criteria for evaluable were completing 24 weeks on the assigned medication and providing at least half of the eight liver tests that were scheduled at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24. Test windows included −/+ 2 days for weeks 1 and 2, and −/+ 7 days for all other weeks. Due to a higher dropout rate in the BUP condition, the initial 1:1 randomization was changed to 2:1, BUP to MET, in December 2007. The initial BUP dose ranged from 2-8mg with increases for persistent withdrawal to a maximum of 16mg on the first day. Dosing was flexible and based on clinical response with further increases up to a maximum of 32mg; the mean maximum daily dose among study participants was 22.1mg (SD = 8.2; median = 24mg). The maximum initial MET dose was 30mg with an additional 5-10 mg if needed on day 1 after 3 or more hours to suppress withdrawal symptoms. As with BUP, MET dosing was based on clinical response and could be increased in 5-10mg increments with no maximum dose specified; the mean maximum MET dose was 93.2mg (SD = 42.2; median = 90mg).

Observed dosing occurred daily except on Sundays and holidays or when take-homes were permitted by local regulations. BUP participants were titrated to a maintenance dose, typically over the first few days; MET participants over several weeks. Both groups remained on study medication for 24 weeks and then tapered to zero over ≤8 weeks or were referred for continuing treatment. Assessments were done at pre-specified intervals and included urine drug tests, self-reported drug use, HIV risk, and blood samples for liver tests.

The analyses presented here were obtained from the HIV Risk Behavior Survey (RBS), an interviewer-administered measure of injecting and sexual HIV risk behavior 38. It takes 6-10 minutes, was administered at baseline and at weeks 12 and 24, and collects information about drug and sexual behaviors over the past thirty days. Questions include number of times injected; sexual activity; condom use; times exchanged sex for drugs, money or both; and HIV-testing history. For these analyses, individual questions were used to create composite scores of injecting and sex risk. The injecting risk composite was defined as reporting at least one risk behavior (sharing needles, not using bleach to clean needles, sharing cooker, front/back loading of syringes [e.g. pulling out the barrel of one syringe and filling it with another or vice-versa]). The sexual risk composite was defined as reporting more than one sexual partner and/or sex without a condom. Injection risk outcomes were modeled as count data and negative binomial distribution was specified in GENMOD procedure. Needle sharing and sexual behavior outcomes were modeled as Yes/No, and the PROC GENMOD/GEE option was used to compare the data.

RESULTS

There were 731 evaluable participants (BUP=340, MET=391) who completed the baseline RBS and of these, 700 (95.8%) completed the 12-week RBS and 705 (96.4%) completed the 24-week RBS. At baseline, BUP participants reported more past 30-day non-heroin opioid use than MET participants (9.3 vs. 7.3 days; p=0.043); but MET participants had a higher percentage of cocaine-positive urine tests (39.0 vs. 29.7; p=0.006) and a higher percentage reported injecting drug use in the past 30 days (69.3 vs. 61.8; p=0.03). Average age and all other baseline characteristics showed no statistically significant differences between groups.

Followup assessments showed significant reductions from baseline (p<0.0008 or more) in the mean number of times heroin, speedball, or other opioids were injected in the last 30 days, as well as the overall number of injection events. Significant reductions (p<0.0001) were also noted in the percentage who shared needles, did not clean shared needles with bleach, shared cookers, engaged in front/back loading, and the needle risk composite score. There were no significant differences between groups on any of these outcomes. The only significant group difference on injecting risk was for amphetamines in which the mean number of times injected rose from 0.05 at baseline to 1.9 at 24 weeks in BUP participants vs. a decrease from 0.29 to 0.22 in MET participants (p<0.05). The mean number of times cocaine was injected dropped approximately equally in both groups but did not meet the threshold for statistical significance.

Sexual risk behaviors in the last 30 days (> one partner, sex without a condom), and sex risk composite were compared across time (baseline, 12- and 24 weeks) and between treatment groups. There was a significant reduction in sex with more than one partner over time and no group differences. Percent having multiple sex partners decreased equally in both groups (p<0.03), however MET participants reported greater reduction in the sex risk composite score than BUP participants (p< 0.05).

Sexual risk behavior was analyzed separately for males and females (Tables 4a and 4b, respectively), and time effect and interactions were found. For males on BUP, the sex risk composite increased over time whereas for males on MET there was a reduction in sex risk over time, and a significant difference between groups with more overall sex risk reduction on MET. For females, there was a significant reduction in the sex risk composite over time with no differences between groups.

Table 4a.

Sexual risk behavior for male

| Variable | Male | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUP | MET | P values | |||||||

| Baseline (n=242) |

12 week FU (n=234) |

24 week FU (n=234) |

Baseline (n=253) |

12 week FU (n=243) |

24 week FU (n=245) |

Tx | Time (visit) |

Tx*time | |

| % Multiple (>1) partners | 5.79 | 8.12 | 5.13 | 5.53 | 3.29 | 3.27 | 0.9728 | 0.1370 | 0.2931 |

| % Unsafe sex (without condom) | 39.26 | 39.32 | 44.02 | 42.29 | 40.74 | 41.22 | 0.2472 | 0.8370 | 0.1279 |

| % Sex risk composite | 41.32 | 45.30 | 47.44 | 46.25 | 42.39 | 44.08 | 0.1575 | 0.5554 | 0.0318 |

Table 4b.

Sexual risk behavior for female

| Variable | Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUP | MET | P values | |||||||

| Baseline (n=98) |

12 week FU (n=92) |

24 week FU (n=96) |

Baseline (n=138) |

12 week FU (n=131) |

24 week FU (n=130) |

Tx | Time (visit) |

Tx*time | |

| % Multiple (>1) partners | 9.18 | 7.61 | 5.21 | 13.04 | 6.11 | 8.46 | 0.6989 | 0.1292 | 0.9470 |

| % Unsafe sex (without condom) | 44.90 | 42.39 | 40.63 | 48.55 | 41.22 | 41.54 | 0.5750 | 0.1055 | 0.5598 |

| % Sex risk composite | 52.04 | 46.74 | 44.79 | 55.80 | 45.80 | 45.38 | 0.5489 | 0.0245 | 0.5433 |

DISCUSSION

These findings show marked and approximately equal reductions in injection and injection related risk among participants who remained in their assigned treatment condition and completed 4 or more blood draws over 24-weeks. Reasons for the small but significant increase in amphetamine use in BUP participants are unclear and may be an incidental finding as it has not been previously reported.

The much smaller but significant decrease in the sexual risk composite among MET as compared to BUP participants could be the result of a greater impact on sexual hormone production among patients taking methadone, particularly males. This would be consistent with reports from the 1970’s that methadone decreases gonadal hormone secretion during the first months of treatment with accompanying reductions in sexual activity 39, 40 and with a more recent study that found much lower total testosterone levels in 83 men on methadone maintenance as compared to 19 on buprenorphine 41. The decrease in sex risk composite among males on MET, and the absence of a decrease in males on BUP (Table 4a), is consistent with these data, and with another study that also found lower testosterone levels in patients on MET as compared to BUP42. These differences in sexual effects could be a reflection of the full opioid agonist effects of MET vs. the partial agonist effects of BUP.

The higher dropout rate among participants assigned to BUP 37 suggests that methadone may be more generally effective than buprenorphine-naloxone at reducing HIV risk over time, at least among individuals who enroll in treatment at methadone clinic sites. Despite these differences in dropout rates, the data clearly show that injecting risk was markedly and equally reduced regardless of medication assignment among those who remained in treatment. This finding indicates that buprenorphine-naloxone, like methadone, is a successful HIV risk reduction intervention for patients who remain in treatment, but with the added advantage of being accessible in settings other than methadone programs in the U.S. For individuals who drop out of buprenorphine-naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, residential treatment, or intensive self-help group participation could be helpful, depending on patient choice and available resources. In addition to the differential dropout rate, a study limitation was that approximately 75% of the participants were Caucasian, thus these findings may not apply to populations with higher representations of minorities. Findings may also differ in populations with higher rates of amphetamine, cocaine or benzodiazepine use.

Overall, these findings further support the importance of expanding availability of evidence-based medical treatments for opioid addiction 43. At the same time it is often difficult to balance expanded access with diversion control. In the case of methadone, one approach that current U.S. law permits but is rarely used, is to involve local pharmacies as medication dispensing stations. Another is to involve primary care providers in methadone treatment as was done in one RCT where stable methadone patients were transferred to primary care for ongoing treatment, however current US law does not allow primary care providers to prescribe methadone for opioid dependence 44. In contrast, such a development has occurred in the U.K. over the past ten years with apparent success in reducing overdose deaths 45, 46

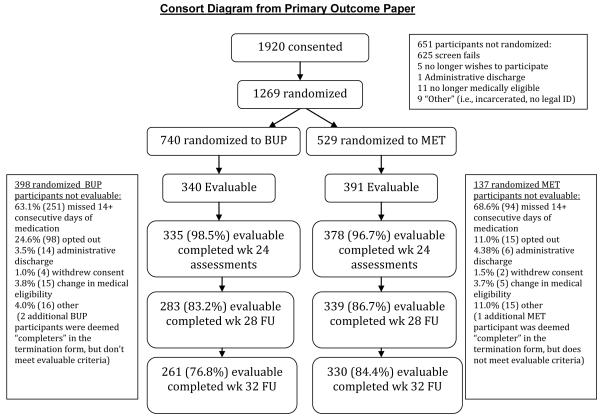

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram from Primary Outcome Paper

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Evaluable Participants

| Demographic Characteristics %, n, except as noted | BUP (n=340) | MET (n=391) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (sd) | 39.3 (11.3) | 38.4 (11.3) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 71.2 (242) | 64.7 (253) |

| Female | 28.8 (98) | 35.3 (138) |

| Ethnicity/Race | ||

| Hispanic | 15.6 (53) | 14.3 (56) |

| White | 72.9 (248) | 79.3 (310) |

| Black or African American | 12.1 (41) | 10.7 (42) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.9 (3) | 0.5 (2) |

| Asian | 0.9 (3) | 0.3 (1) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Other | 12.7 (43) | 8.7 (34) |

| Unknown | 0.3 (1) | 0.5 (2) |

| Self-Reported Mean Days of Drug Use in the Past 30 Days (sd) | ||

| Cocaine | 3.0 (6.3) | 2.9 (5.9) |

| Heroin | 24.3 (9.9) | 24.2 (9.8) |

| Non-heroin opioids* | 9.3 (12.0) | 7.3 (11.0) |

| Amphetamines | 0.8 (2.5) | 1.0 (3.2 |

| Self-Reported Mean Days of Injection Drug Use (sd) | ||

| Heroin by injection | 20.0 (12.9) | 20.6 (12.3) |

| Non-heroin opioids by injection | 0.8 (4.0) | 0.9 (3.9) |

| Percent Positive Urine Drug Test (n) | ||

| Opiates (morphine) | 85.3 (290) | 86.7 (339) |

| Oxycodone | 14.7 (50) | 15.1 (59) |

| Cocaine** | 29.7 (101) | 39.4 (154) |

| Benzodiazepines | 19.7 (67) | 18.7 (73) |

| Cannabis | 25.3 (86) | 20.5 (80) |

| HIV Risk Behaviors Reported for Last 30 Days | ||

| Mean times injected w/shared needles | 2.1 (6.1) | 4.8 (25.7) |

| % Reporting multiple sex partners (n) | 6.8 (23) | 8.2 (32) |

| % Reporting injection drug use past 30 days*** (n) | 61.8 (210) | 69.3 (271) |

| Laboratory Results | ||

| Hepatitis B Surface Antibody | 32.6 (97) | 35.3 (138) |

| Hepatitis C Core Antibody | 1.5 (5) | 1.5 (6) |

| Hepatitis B Surface Antigen | 0.3 (1) | 0.5 (2) |

| Hepatitis C Antibody | 43.5 (148) | 43.5 (170) |

| HCV RNA | 32.9 (112) | 28.4 (111) |

| HIV positive | 1.2 (4) | 0.5 (2) |

t = 2.03; p – 0.043;

Chi-square = 7.5, p = 0.0062;

Chi-square =4.60, p=0.0320

Table 2.

Injection drug use and needle risk behavior

| Variable | BUP | MET | P values a, b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=340) |

12 week FU (n=326) |

24 week FU (n=330) |

Baseline (n=391) |

12 week FU (n=374) |

24 week FU (n=375) |

Tx | Time (visit) |

Tx*time | |

| Mean number of times injected cocaine | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.77 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.8813 | 0.1861 | 0.7585 |

| Mean number of times injected heroin | 64.6 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 65.3 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 0.6695 | <.0001 | 0.4797 |

| Mean number of times injected speedball | 2.3 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 4.1 | 0.74 | 0.42 | 0.5375 | <.0001 | 0.9633 |

| Mean number of times injected other opiates | 1.0 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.7 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.9919 | 0.0008 | 0.7064 |

| Mean number of times injected Amphetamines | 0.05 | 0.07 | 1.9 | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.0497 | 0.6135 | 0.0363 |

| Mean number of times injected Total | 69.7 | 3.83 | 5.6 | 73.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 0.8756 | <.0001 | 0.9407 |

| % Shared needles | 14.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 14.1 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 0.2008 | <.0001 | 0.1029 |

| % Didn’t clean shared needles w/ bleach | 10.3 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 9.9 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 0.3692 | <.0001 | 0.3009 |

| % Shared cooker | 17.1 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 18.9 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 0.7262 | <.0001 | 0.2959 |

| % Front/back load (any) | 21.2 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 20.5 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 0.7049 | <.0001 | 0.5311 |

| % Needle risk composite | 25.0 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 24.8 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 0.4022 | <.0001 | <.1923 |

PROC GENMOD (Negative binomial distribution);

PROC GENMOD (GEE) for binary variables

Table 3.

Sexual risk behavior

| Variable | BUP | MET | P values c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=340) |

12 week FU (n=326) |

24 week FU (n=330) |

Baseline (n=391) |

12 week FU (n=374) |

24 week FU (n=375) |

Tx | Time (visit) |

Tx*tim e |

|

| % Multiple (>1) partners | 6.8 | 7.9 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 0.6750 | 0.0329 | 0.3539 |

| % Unsafe sex (without condom) | 40.9 | 40.2 | 43.0 | 44.5 | 40.9 | 41.3 | 0.1602 | 0.2063 | 0.0914 |

| % Sex risk composite | 44.4 | 45.7 | 46.7 | 49.6 | 43.6 | 44.5 | 0.0894 | 0.0490 | 0.0272 |

PROC GENMOD (GEE) for binary variables

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals and personnel provided suggestions for the study design and supplied Suboxone. The following networks from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network participated in this study: The Pacific Northwest Node (Dennis Donovan, PhD) and Evergreen Treatment Services (Paul Grekin, MD; Andrew Saxon, MD, Ron Jackson, MSW); the Oregon Hawaii Node (Dennis McCarty, PhD) and CODA Inc. (Joshua Boverman, MD, Jeffrey Hayes, MD, Jonathan Berman, MD, Katharina Wiest, PhD); the California/Arizona Node (James Sorenson, PhD) and Bi-Valley Medical Clinic (John McCarty, MD, Esther Billingsley, NP, Lori Matthews, NP); the New England Node (Kathleen Carroll, Ph.D.) and Connecticut Counseling Centers (Hansa Shah, MD, Mark Kraus, MD, Michael Feinberg, MD,) and Yale and Hartford Dispensary (Gerardo Gonzalez, MD, R. Douglas Bruce, MD, Peter Strong, MD, Cindy Gilligan, PA); the Delaware Valley Node (George Woody, MD) and NET Steps (John Carroll, Richard Hellander, MD, Trusandra Elaine Taylor, MD, June Topacio, MD, Angela T. Walker, MD, Bernard Harris, MD, MPH); the Pacific Region Node (Walter Ling, MD), and Bay Area Addiction Research & Treatment (Judith Martin, MD, Laurene Spencer, MD., Audrey Sellers, MD, Carolyn Schuman, MD; Allan Cohen, MA, MFT) and Matrix Institute (Roger Donovick, MD, Matthew Torrington, MD, Michael McCann, MA); and the New York Node (John Rotrosen, MD) and Addiction Research & Treatment Corp (Lawrence Brown, Jr., MD, MPH, Steven Kritz, MD); the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DSC); EMMES Corporation (CCC); the Center for Clinical Trials Network at the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Supported by NIDA grants: U10- (W. Ling); U10-DA013714 (D. Donovan); U10 DA-13043, KO5 DA-17009 (G. Woody)

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: Authors disclosing relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations are: Andrew Saxon: Paid consultant to Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals; Walter Ling: Paid consultant to Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals; R. Douglas Bruce: Research grant support from Gilead Sciences, Inc., Merck & Co., Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer, Inc., and honorarium from Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals; Yuliya Lokhnygina: Paid consultant to Johnson & Johnson. All other authors report no financial or other possible conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haverkos HW. HIV/AIDS and drug abuse: epidemiology and prevention. J Addict Dis. 1998;4:91–103. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, et al. Drug abuse treatment: a national study of effectiveness. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball JC, Lange RL, Myers CP, et al. Reducing the risk of AIDS through methadone maintenance treatment. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29:214–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball JC, Ross A. The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Springer Verlag; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, et al. Overview of one-year follow-up outcomes in the substance abuse treatment outcome study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gowing L, Farrell R, Bornemann R, et al. Methadone treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(2):193–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartel DM, Schoenbaum EE. Methadone treatment protects against HIV infection: two decades of experience in the Bronx, New York City. Public Health Reports. 1998;113:107–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrinson P, Ali R, Buavirat A. Key findings from the WHO collaborative study on substitution therapy for opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS. Addiction. 2008;103:1484–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caplehorn JRM, Ross MW. Methadone maintenance and the likelihood of risky needle sharing. Int J Addict. 1995;30:685–698. doi: 10.3109/10826089509048753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among in-and out-of-treatment intravenous drug users: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian HZ, Hao C, Ruan Y, et al. Impact of methadone on drug use and risky sex in China. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008 Jun;34(4):391–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong K, Lee S, Lim W, et al. Adherence to methadone is associated with a lower level of HIV-related risk behaviors in drug users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24(3):233–23. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger DS, et al. The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA. 1993;269(15):1953–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avants SK, Margolin A, Sindelar JL, et al. Day treatment versus enhanced standard methadone services for opiod-dependent patients: A comparison of clinical efficacy and cost. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):27–33. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth RE, Crowley T, Zhang Y. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention and effectiveness: out-of-treatment opiate injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1196;42:11–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwiatkowski CF, Booth RE. Methadone maintenance as HIV risk reduction with street-recruited injecting drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:483–489. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, et al. Reduced injection risk and sex risk behaviors after drug misuse treatment: results from the National Treatment Outcome Research Study. AIDS Care. 2002;14:177–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiede H, Hagan H, Murrill CS. Methadone treatment and HIV and hepatitis B and C risk reduction among injectors in the Seattle area. Journal of Urban Health. 2000;77(3):331–344. doi: 10.1007/BF02386744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control Antibodies to a retrovirus etiologically associated with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) in populations with increased incidences of the syndrome. MMWR. 1984;33:377–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novick DM, Joseph H, Croxon TS, et al. Absence of antibody to human immunodeficiency virus in long term, socially rehabilitated methadone maintenance patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blix O, Gronbladh L. Impact of methadone maintenance treatment on the spread of HIV among IV heroin addicts in Sweden. In: Loimer N, Schmid R, Springer A, editors. Drug Addiction and AIDS. Springer-Verlag Wien; New York: 1991. pp. 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss AR, Vranizan K, Gorter R, et al. HIV seroconversion in intravenous drug users in San Francisco, 1985-1990. AIDS. 1994;8:223–231. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serpelloni G, Carrieri MP, Rezza G, et al. Methadone treatment as a determinant of HIV risk reduction among injecting drug users: a nested case-controlled study. AIDS Care. 1994;6:215–220. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorenson JL, Copeland AL. Drug abuse treatment as an HIV prevention strategy: a review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell M, Gowing L, Marsden J, et al. Effectiveness of drug dependent treatment in HIV prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16S:S67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan L, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, et al. Decreasing international HIV transmission: the role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100:150–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg KM, Litwin A, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy improves adherence and viral load in drug users attending methadone maintenance clinics: A randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(2-3):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jasinski DR, Pevnick JS, Griffith JD. Human pharmacology and abuse potential of the analgesic buprenorphine. A potential agent for treating narcotic addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:501–516. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770280111012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: Ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569–580. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson RE, Jaffe JH, Fudala PJ. A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. JAMA. 1992;267:2750–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, et al. buprenorphine versus methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence: Self reports, urinalysis, and addiction severity index. J Clinical Psychopharm. 1996;16:58–67. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fudala PJ, Yu E, Mac Fadden W, et al. Effects of buprenorphine and naloxone in morphine-stabilized opioid addicts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA. Buprenorphine: Its Role in Preventing HIV Transmission and Improving the Care of HIV-Infected Patients with Opioid Dependence. HIV/AIDS. 2005;41:891–896. doi: 10.1086/432888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan LE, Moore BA, Chawarski MC, et al. Buprenorphine/naloxone treatment in primary care is associated with decreased human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooner RK, Greenfield L, Schmidt CW, et al. Antisocial personality disorder and HIV infection among intravenous drug abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 1993 Jan;150(1):53–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lott DC, Strain EC, Brooner RK, et al. HIV Risk behaviors during pharmacologic treatment for opioid dependence: A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saxon AJ, Ling W, Hillhouse M, et al. Buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone effects on laboratory indices of liver health: a randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013 Feb 1;128(1-2):71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.002. PMC3543467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, et al. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanbury R, Cohen M, Stimmel B. Adequacy of sexual performance in men maintained on methadone. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1977;4(1):13–20. doi: 10.3109/00952997709002743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crowley TJ, Simpson R. Methadone dose and human sexual behavior. Int J Addict. 1978 Feb;13(2):285–95. doi: 10.3109/10826087809039281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hallinan R, Byrne A, Agho K, McMahon CG, Tynan P, Attia J. Hypogonadism in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. International J. Andrology. 2009;32(2):131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bliesener N, Albrecht S, Schwager A, Weckbecker K, Lichtermann D, Klingmuller D. Plasma testosterone and sexual function in men receiving buprenorphine maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. J. of Clin. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90(1):203–206. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brissette S, Kerr T, Marsh DC, Schackman BR, Wood E, Montaner JS. A call for evidence-based medical treatment of opioid dependence in the United States and Canada. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1462–1469. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG, Chawarski M, Pakes JP, Pantalon MV, Schottenfeld RS. Methadone maintenance in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1724–1731. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strang J, Manning V, Mayet S, Ridge G, Best D, Sheridan J. Does prescribing for opiate addiction change after national guidelines? Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing to opiate addicts by general practitioners and hospital doctors in England, 1995-2005. Addiction. 2007;102:761–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strang J, Hall W, Hickman M, Bird SM. Impact of supervision of methadone consumption on deaths related to methadone overdose (1993-2008): analyses using OD4 index in England and Scotland. British Medical Journal. 2010;341(16):341, c4851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]