Abstract

Problem

How can physicians incorporate the electronic health record (EHR) into clinical practice in a relationship-enhancing fashion (“EHR ergonomics”)?

Approach

Three convenience samples of 40 second-year medical students with varying levels of EHR ergonomic training were compared in the 2012 spring semester. All participants first received basic EHR training and completed a pre-survey. Two study groups were then instructed to use the EHR during the standardized patient (SP) encounter in each of four regularly scheduled Doctoring (clinical skills) course sessions. One group received additional ergonomic training in each session. Ergonomic assessment data were collected from students, faculty, and SPs in each session. A post-survey was administered to all students, and data were compared across all three groups to assess the impact of EHR use and ergonomic training.

Outcomes

There was a significant positive effect of EHR ergonomics skills training on students’ relationship-centered EHR use (P < .005). Students who received training reported that they were able to use the EHR to engage with patients more effectively, better articulate the benefits of using the EHR, better address patient concerns, more appropriately position the EHR device, and more effectively integrate the EHR into patient encounters. Additionally, students’ self-assessments were strongly corroborated by SP and faculty assessments. A minimum of three ergonomic training sessions was needed to see an overall improvement in EHR use.

Next Steps

In addition to replication of these results, further effectiveness studies of this educational intervention need to be carried out in GME, practice, and other environments.

Problem

Collaborative use of the electronic health record (EHR) by patients and physicians can contribute to improved quality of care, enhance the decision-making process, empower patients to participate in their own care, and increase the patient-centeredness of interactions.1,2 However, the EHR is perceived by some to be a “third party to a conversation” between a patient and a physician, whereby the EHR forms its own identity and both physicians and patients project their perceptions onto this identity.3,4 Some have suggested that medical training needs to address the addition of the EHR into the physician-patient relationship in order to fully realize the benefits of EHRs5,6 and that the effective use of computers in clinician-patient communication may largely depend on clinicians being trained with baseline skills in EHR use.7

Since its inception in 2007, the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix (COM-P) curriculum has included significant instruction in biomedical informatics across all four years of the medical school curriculum.8 Born into the computing age, current medical students are generally at ease with the use of computers; however, we wondered whether additional EHR training would advantage them in using computers in clinical encounters in a relationship-enhancing fashion.

Although many studies have focused on the effects of EHR use on physician-patient relations, few studies have directly examined the integration of relationship-centered EHR training in undergraduate medical education to promote these relations. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the hypothesis that an educational intervention for second-year medical students improves their ability to use the EHR in a way that enhances, rather than detracts from, patient-provider interaction (“EHR ergonomics”) during a standardized patient (SP) encounter.

Approach

We performed a comparative study at COM-P of three convenience samples of second-year medical students to examine the effect of EHR ergonomic training on their ability to use the EHR in a relationship-enhancing fashion during required SP encounters. All COM-P students are required to complete SP encounters as part of a Doctoring course in their preclerkship years during which they learn history taking, physical examination, presentation, and clinical reasoning skills. This study was done in collaboration with researchers at Vanderbilt University, and the Institutional Review Boards at The University of Arizona and Vanderbilt University approved all study procedures.

EHR ergonomic training content was incorporated into each of four Doctoring SP encounters (DS1, DS2, DS3, and DS4) scheduled from February through March of 2012, and survey items related to EHR ergonomics were included in the assessment materials for each of these sessions. This interval was selected since it immediately preceded the onset of the participants’ clerkship experiences. During the study period, students received one of three different levels of exposure to EHR systems and ergonomic training based on their pre-assigned Doctoring session schedule (students [n = 40] were randomly assigned for the entire academic year to Tuesday [n = 13], Wednesday [n = 12], or Thursday [n = 15] afternoon groups). All students received a two-hour basic EHR navigation training session at the beginning of the study period. During this initial training session, students completed a pre-survey that collected information about participants’ demographics and computer use, and they completed a post-survey after the series of Doctoring sessions (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1) [[LWW INSERT LINK]].

The Tuesday Doctoring students received only the initial basic EHR training with no additional ergonomic training, and no EHR was available for use during their SP encounters (Control I). Wednesday students received only basic EHR training and no ergonomic training and were expected to use the EHR available to them during SP encounters (Control II). Thursday students received both basic EHR training and additional ergonomic training and were expected to use the EHR available to them during SP encounters (Treatment).

In DS1, all students received an exercise to refresh the knowledge and skills learned from the basic EHR training session. Experienced COM-P faculty members fully aware of the objectives of this study (M.M. and S.K.) conducted a “read-only” EHR exercise reviewing vital signs and confirming the medication list with an SP using the EHR for all three groups. In DS2 and DS3, only students in the Treatment group received 15 minutes of EHR ergonomic training at the beginning of each Doctoring session led by two COM-P faculty members (H.S. and W.E.) as detailed in Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 [[LWW INSERT LINK]] and summarized here:

In DS2, students were instructed how to introduce the use of the laptop-based EHR into the SP encounter by explaining the benefits of using the EHR. The slight distraction of logging into the EHR was framed to the patient as positive in that their information was secure within the EHR. A script was provided for use by students and was demonstrated through role-play by the instructors.

In DS3, students were instructed on optimizing positioning of the laptop to effectively integrate the EHR into their interactions with the patient such that the patient is actively involved in viewing and reviewing their information on the laptop. This was demonstrated through role play by instructors.

In DS4, students were encouraged to share their experiences from DS2 and DS3. Insights and challenges were discussed, reflected, and problem solved by the group and the instructors.

All students were asked to perform the standard tasks of reviewing vital signs and confirming a medication list during their SP encounters in all four Doctoring sessions. Customized ergonomic assessment items were created for students, faculty, and SPs to assess the students’ EHR use during SP encounters in the Doctoring sessions (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 3) [[LWW INSERT LINK]] based on the learning objectives in the educational intervention (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2) [[LWW INSERT LINK]]. Data from student self-assessments, faculty observation and narrative assessments, and SP ergonomic assessments were collected immediately following each encounter. All SP encounters were video-recorded as part of standard COM-P practice.

Outcomes

To determine whether there were any differences in characteristics among the three study groups (Control I, Control II, and Treatment), we used the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical variables, and a likelihood ratio test of proportional odds models for ordinal variables. To examine the overall effect of EHR ergonomic training on students’ self-assessment of their EHR use, we fitted a linear model with the difference of the ergonomic assessment scores reported in the pre- and post-surveys as response, and study group and baseline score were included as independent variables. We also evaluated the effect of each ergonomic training session on EHR usage by fitting a generalized least squares linear model of ergonomic assessment score difference between DS1 and each of the subsequent sessions to adjust for repeated measurements from each student. We included the following variables as covariates in our model: study group, Doctoring session, ergonomic assessment score in DS1, and an interaction term for study group and Doctoring session variables. We used unstructured or compound symmetry covariance structure (determined by likelihood ratio test) to account for within-subject correlation. Scores obtained from the ergonomic assessment items were fitted with separate models, and Wald statistics were used to assess patterns of results. Two-sided P-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. We calculated Cronbach’s alpha to evaluate the internal consistency of the ergonomic assessment items. All analyses were conducted using R 2.13.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics among the three study groups comprising the 40 students who completed this study, including prior personal use of EHRs (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 40 Second-Year Medical Student Participants by Study Group in a Study of the Effect of Electronic Health Record Ergonomics Training on Performance During Standardized Patient Encounters, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, 2012

| Characteristic | Total no. of respondents |

Control Ia | Control IIa | Treatmenta | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of respondents with nonmissing

data |

-- | 13 | 12 | 15 | -- |

| Age | 40 | -- | -- | -- | 0.44b |

| Mean±SD | -- | 25.2±2.1 | 26.2±2.2 | 25.3±2.5 | |

| Gender | 40 | -- | -- | -- | 0.19c |

| Male, no. (%) | -- | 7 (54) | 9 (75) | 6 (40) | -- |

| Female, no. (%) | -- | 6 (46) | 3 (25) | 9 (60) | -- |

| Race | 38 | -- | -- | -- | 0.36c |

| White, no. (%) | -- | 8 (62) | 9 (75) | 8 (62) | -- |

| Black, no. (%) | -- | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Asian, no. (%) | -- | 4 (31) | 2 (17) | 2 (15) | -- |

| Other, no. (%) | -- | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (23) | -- |

| Computer use (hours/week) | 40 | -- | -- | -- | 0.97b |

| Mean±SD | -- | 39±19 | 38±15 | 40±21 | |

| Computer sophistication | 40 | -- | -- | -- | 0.38d |

| Very sophisticated, no. (%) | -- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | -- |

| Sophisticated, no. (%) | -- | 2 (15) | 4 (33) | 5 (33) | -- |

| Neither sophisticated nor unsophisticated, no. (%) |

-- | 8 (62) | 5 (42) | 7 (47) | -- |

| Unsophisticated, no. (%) | -- | 3 (23) | 3 (25) | 2 (13) | -- |

| Very unsophisticated, no. (%) | -- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Personally used EHR, no. (%) | 30 | 8 (62) | 10 (83) | 12 (80) | 0.39c |

Abbreviations: EHR = electronic health record.

The Control I study group received basic EHR training and did not use the EHR in standardized patient encounters. The Control II and Treatment study groups received basic EHR training and were instructed to use the EHR during standardized patient encounters. The Treatment study group received additional EHR ergonomic training.

Calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Calculated using the Chi-square test.

Calculated using the proportional odds likelihood ratio test.

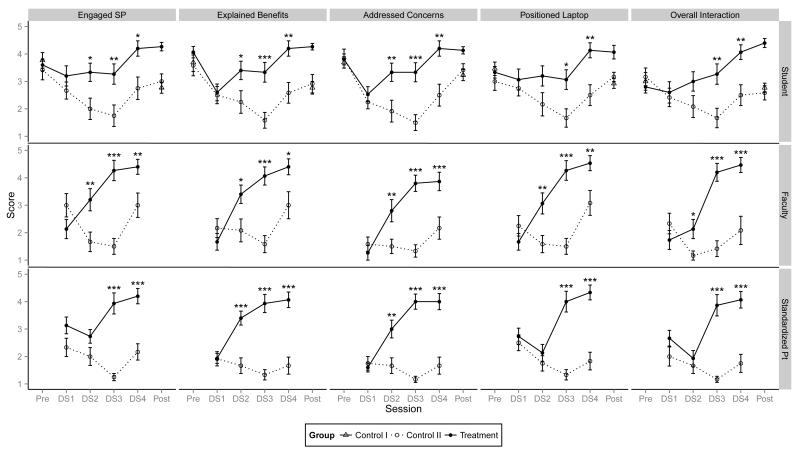

The mean scores of each of our five ergonomic assessment items in the pre- and post-surveys are presented in Figure 1. We found a significant difference between the pre- and post-survey scores compared across the three study groups for all ergonomic student self-assessment items (P < .005, Table 2) indicating that EHR use improved with EHR ergonomic training. The five ergonomic assessment items used in this study showed high internal consistency; Cronbach’s alphas were 0.81, 0.90, 0.88, 0.94, 0.98, and 0.97 when evaluated for the pre-survey, post-survey, and each of the four Doctoring sessions, respectively.

Figure 1.

Student, standardized patient (SP), and faculty assessment scores of 40 students’ electronic health record (EHR) use in SP encounters, and students’ pre- and post-survey scores from an intervention to provide “EHR ergonomics” training during Doctoring Sessions, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, February-March, 2012. Significant increases in scores between the first Doctoring session (DS1) and the comparison sessions (DS2, DS3, and DS4) are indicated by the * just above the corresponding comparison session (* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001).

Table 2.

Comparison of Differences in 40 Second-Year Medical Students’ Self-Assessment Scores for Electronic Health Record Ergonomics Before (Pre) and After (Post) Doctoring Sessions for Study Groups in a Study of the Effect of Electronic Health Record Ergonomics Training on Performance During Standardized Patient Encounters, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, 2012

| Assessment item | Treatment (Post – Pre) – Control II (Post – Pre)b | Control II (Post – Pre) – Control I (Post – Pre)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-valuea | Estimatec | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| Engagement: Students are able to use the EHR effectively to engage with the patient. |

< .001 | 1.23 | (0.67, 1.78) | 0.31 | (−0.27, 0.89) |

| Benefits: Students will understand and be able to articulate the benefits of using the EHR and laptop computer to their patients. |

< .001 | 1.23 | (0.61, 1.85) | 0.18 | (−0.46, 0.81) |

| Concerns: Students will be able to address patient concerns and questions about confidentiality of the EHR. |

.003 | 0.72 | (0.22, 1.23) | 0.16 | (−0.36, 0.69) |

| Position: Students will understand and be able to appropriately position the laptop for effective use in the patient encounter. |

< .001 | 0.87 | (0.28, 1.46) | 0.29 | (−0.33, 0.90) |

| Interactions: Students will be able to effectively integrate the EHR into their interactions with the patient such that the patient is actively involved in viewing and reviewing their information on the laptop. |

< .001 | 1.87 | (1.33, 2.41) | −0.21 | (−0.77, 0.34) |

Abbreviations: EHR = electronic health record;

The null hypothesis is that after accounting for baseline score, there is no difference in post-pre improvement between study groups.

The Control I study group received basic EHR training and did not use the EHR in standardized patient encounters. The Control II and Treatment study groups received basic EHR training and were instructed to use the EHR during standardized patient encounters. The Treatment study group received additional EHR ergonomic training.

Estimate on the difference in post-pre improvement between the two study groups indicated in the column header. The estimates were derived from the linear regression model as described in the Approach section.

Post survey responses indicated that compared to participants in the Control II group, students in the Treatment group felt that they were able to use the EHR more effectively to engage with the patient, better articulate the benefits of using EHR, better address patient concerns, more appropriately position the EHR device, and more effectively integrate EHR into the patient encounter. On the other hand, Control I and Control II participants, both of which received no ergonomic training in the study, did not exhibit any significant differences between pre- and post-survey ergonomic assessment scores.

To determine whether ergonomic training yielded incremental improvement in students’ relationship-centered EHR use over multiple sessions, we also collected these same items from students in Control II and Treatment groups as well as from SPs and faculty after each SP encounter for each of the four Doctoring sessions. We defined incremental improvement in EHR use as the difference between ergonomic assessment scores in the first session and each of the subsequent sessions (i.e., DS1 vs. DS2, DS1 vs. DS3, DS1 vs. DS4), as shown in Figure 1 and in Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 [[LWW INSERT LINK]]. A similar pattern emerged across students, faculty, and SPs: The difference in scores for some, but not all, EHR assessment items between DS1 and DS2 was significantly greater for the Treatment than for the Control II group. However, the difference in scores between the DS1 and DS3 for the Treatment group was significantly greater across all five ergonomic assessment items, indicating a minimum of three ergonomic training sessions was necessary to see overall improvement in EHR use. Additionally, student self-assessments were well corroborated by SP and faculty assessments, suggesting that students’ self-perceptions were consistent with their performance as observed by SPs and faculty during SP encounters.

Next Steps

This study demonstrates that our students who received simple instruction in EHR ergonomics were much better able to utilize the EHR in a relationship-enhancing fashion compared to their peers who did not receive this training. Given the rapid and widespread deployment of EHRs into clinical settings and the positive potential of collaborative use of the EHR described above, these techniques could positively impact clinician EHR training in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Further studies should be carried out to determine the effect of such training for practicing clinicians, including physicians, nurses, and allied health personnel.

Our approach was limited in several respects. It was carried out in a highly controlled environment focused on the simple task of accessing vital signs and medications in order to study the direct effects of ergonomic training; however, it is not clear whether the beneficial effects of training observed here would translate into other less-controlled and more robust clinical environments. Since our study focused on a preclerkship cohort, it is difficult to know what impact, if any, it will produce as these students move into clerkships, residencies, and practice environments.

There are several areas that merit further study. First, it would be interesting to determine whether EHR ergonomic skills carry forward or grow subsequently as students move through clerkships and residency. A variety of clinical environments, EHR systems, and clinical specialties, including nursing and allied health personnel, should be studied to determine whether effects of preclerkship EHR training are still evident in diverse and complex real-world clinical environments. Refinements to the training content and methods could be informed by “real-world” observations. Second, while the literature suggests that these skills would have a positive impact on patients with regard to shared decision making, other patient outcomes, such as patient satisfaction and compliance, are areas that may warrant further investigation. Similarly, we would recommend further exploration into the effects of EHR ergonomic skills in other areas, including provider satisfaction, efficiency, accuracy, and burnout.

We are not aware of the incorporation of any similar training into medical school or practice environments. As EHR implementation accelerates, our findings suggest that such training may be a valuable addition to existing conventional EHR training programs for all clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lou Clark for her tireless and valuable work in preparing the Standardized Patients to participate in this study and Liz Williams for skillfully implementing the student assessment tools used to gather data for this study.

Funding/Support: The authors report funding from the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Innovative Advances in Medical Education Program, and REDCap grant support UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Approval for data collection, review, and analysis was obtained from the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board / Human Subjects Protection Program and the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Contributor Information

Dr Howard Silverman, Department of Biomedical Informatics, and Professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine and Bioethics & Medical Humanism, The University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona, and Clinical Professor of Biomedical Informatics at Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona..

Dr Yun-Xian Ho, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee..

Dr Susan Kaib, Doctoring Program, and Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona..

Dr Wendy Danto Ellis, Scottsdale Healthcare Family Medicine Residency and Scottsdale Healthcare NOAH (Neighborhood Outreach Access to Health) clinics, Scottsdale, Arizona, and Instructor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona..

Dr Marícela P. Moffitt, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona..

Dr Qingxia Chen, Departments of Biostatistics and Biomedical Informatics, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee..

Hui Nian, Department of Biostatistics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee..

Dr Cynthia S. Gadd, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee..

References

- 1.Margalit RS, Roter D, Dunevant MA, Larson S, Reis S. Electronic medical record use and physician-patient communication: An observational study of Israeli primary care encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson KB, Serwint JR, Fagan LA, Thompson RE, Wilson ME, Roter D. Computer-based documentation: Effects on parent-provider communication during pediatric health maintenance encounters. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):590–598. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ventres W, Kooienga S, Vuckovic N, Marlin R, Nygren P, Stewart V. Physicians, patients, and the electronic health record: An ethnographic analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(2):124–131. doi: 10.1370/afm.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lown BA, Rodriguez D. Commentary: Lost in translation? How electronic health records structure communication, relationships, and meaning. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):392–394. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318248e5ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glick TH, Moore GT. Time to learn: The outlook for renewal of patient-centred education in the digital age. Med Educ. 2001;35(5):505–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran M. [Accessed March 21, 2014];Making the computer invisible: It’s all about the personal contact. http://www.amaassn.org/amednews/2006/02/13/bisa0213.htm.

- 7.Frankel R, Altschuler A, George S, et al. Effects of exam-room computing on clinician-patient communication: A longitudinal qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):677–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman H, Cohen T, Fridsma D. The evolution of a novel biomedical informatics curriculum for medical students. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):84–90. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823a599e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.