Introduction

African Americans tend to experience worse health than white Americans, and racial inequalities in health have persisted across time despite major advances in the post-Civil Rights era (Williams and Sternthal 2010). Specifically, African Americans have higher mortality rates than Americans of European descent for the majority of the fifteen leading causes of death, including cancer, hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes (Kung et al. 2008). Research also indicates that low-income African Americans may encounter more environmental factors conducive to negative health outcomes, such as exposure to harmful toxins and pollution (Williams and Mohammed 2009). Additionally, low-income urban African Americans are disproportionately exposed to violence and crime, which can increase stress and contribute to negative physical and mental health outcomes including low birth-weights and post-traumatic stress disorder (Morenoff 2003, Dohrenwend et al. 1992). Because African Americans, on average, have lower socioeconomic status than those of European descent in the United States, they also disproportionately experience the negative effects of poverty on health, further compounding inequalities tied to race (Nguyen and Peschard 2003).

Though use of health services is only one of many factors, research has consistently identified underutilisation to be significantly correlated with poor health outcomes (LaVeist et al. 2003). Broadly, African American men and women tend to use health services less than their white counterparts – meaning health problems are frequently diagnosed later when they are more serious, contributing to worse outcomes (Wright and Perry 2010, Zuvekas and Fleishman 2008). These patterns of underutilisation are particularly problematic since low-income women of color are disproportionately in need of health services (Wyn et al. 2004). For instance, African American women are more likely than white women to identify their health as fair to poor and more likely to report a physical condition that limits routine activities (Wyn et al. 2004). Further, low-income African American women may experience worse mental and physical health due to the compounding effects of their gender, race, and class statuses such that they may simultaneously encounter sexism, racial discrimination, and classism in their daily lives (Perry et al. 2013).

Despite the health implications of racial and gender disparities in utilisation, the majority of research in this area focuses on acute physical or mental health services, and service utilisation among the elderly (Shenson et al. 2012, Ojeda and Bergstresser 2008, Williams and Mohammed 2009). In addition, with the exception of studies examining end of life care and cancer treatment decisions, few existing utilisation studies examine the role of factors like religiosity, cultural attitudes and experiences, and social support that may be particularly relevant to African American women (Gerend and Pai 2008, Johnson et al. 2005). Importantly, the findings of this extant research cannot be expected to translate to preventative care utilisation. That is, given the differences between making time-sensitive, life-or-death decisions and making less urgent, “everyday” choices about basic health maintenance, arguing that factors influencing these differing types of choices operate similarly is untenable. These gaps in the literature are also problematic since preventative care – especially having a yearly comprehensive physical exam – is essential for maintaining good health through early disease identification and the management of chronic conditions like hypertension and diabetes that are prevalent among African Americans (Williams and Mohammed 2009). Further, preventative care in the United States often serves as a gateway to accessing other services, such as care from specialist physicians.

The purpose of this research is to expand our knowledge of the mechanisms underlying African American women’s usage of preventative care services; specifically, having received an annual physical exam. Using survey data from 206 low-income, urban African American women, self-reported barriers to preventative care and alternative sources of health information are first described. Subsequently, we examine the relationship between having an annual physical and a variety of culturally relevant factors, with a particular emphasis on how differing levels of social support from friend and family networks and experiences of racist life events and cultural mistrust are associated with patterns of utilisation among this underserved population.

Access to services

Since early in the development of health services research, economic and access factors have been considered key determinants of utilisation. For example, according to Andersen’s Health Behavior Model (1968), high socioeconomic status (SES) and living in advantaged communities predispose individuals to use health services. Likewise, income, insurance status, and the affordability of care enable a person with health care needs to seek services. Research suggests that this is especially true for those seeking preventative care services, as lower-SES adults are less likely to have physical examinations, immunisations, and other basic forms of preventative care (Wright and Perry 2010, Maciosek et al. 2010, Prus 2007).

Empirical research examining delays and abstention from usage of health services among African American women has consistently found that economic factors influence utilisation (Wyn et al. 2004). Broadly, regardless of race, research shows that those with insurance are more likely to utilise health services when compared to those without insurance (Patel et al. 2010, DeVoe et al. 2003). This trend may have special relevance for African American women, as estimates suggest that over 20% of African American women have no health insurance, and they are less likely to have employment-based insurance than white women (Snipes et al. 2009, Wyn et al. 2004).

Continuity of care has also been identified as a factor influencing utilisation choices. Namely, those who have a regular physician tend to use health services more consistently (Blackwell et al. 2009, DeVoe et al. 2008, Ettner 1999, Sox et al. 1998). Additionally, individuals with a usual source of care tend to have fewer emergency department visits and shorter hospitalisations (DeVoe et al. 2003). This research indicates that having a usual physician may be of paramount interest when examining preventative care utilisation.

Racial attitudes and experiences

In addition to examining more traditional predictors of utilisation, it is also critical to link low-income African American women’s help-seeking decisions to their culturally-specific attitudes and experiences. Importantly, experiences of racism and sexism linked to both racial and broader cultural differences with dominant European American society have significant effects on people of color. While it is well established that racial discrimination can have myriad consequences on morbidity and mortality through the stress process and other pathways, less is understood about how such experiences might shape health service utilisation (Thoits 2010, Todorova et al. 2010, Higginbottom 2006). Some research suggests that the Eurocentric orientation of medical institutions (i.e. emphasis on Western biomedical beliefs and practices coupled with little recognition of alternative beliefs and healing practices, etc.) may foster sentiments of cultural mistrust among African Americans whose beliefs or values are marginalised in these settings (Chandler 2010, Blank et al. 2002). For example, fear of racial discrimination in medical facilities has been found to deter African Americans from utilising available services (Shavers et al. 2012, Lee et al. 2009). Further, when compared to whites, African Americans report lower levels of trust in both their physician and in the health care system, and express greater concerns regarding the quality of care (Wyn et al. 2004). In turn, African American women with low levels of trust in their primary care provider are less likely to use and recommend preventative services (Yang et al. 2011). In all, racial attitudes and experiences may have a greater and more measureable impact on the use of some preventative care services, like an annual physical, which are perceived as less urgent or necessary than other types of health care services.

Social support

In addition to discrimination and cultural mistrust, social networks – and particularly social support – may be an especially important consideration when examining patterns of health care utilisation among low-income African American women. African American women are embedded in social networks that influence health decisions and help-seeking behaviors, and evidence suggests their networks are typically large, highly supportive, and comprised of extended kin (Brown 2008). While past research has already found social support to be an important resource for African American women with severe medical needs, considerably less is known about the effect of African American women’s extended kinship networks on usage of preventative care services (Tang et al. 2008). Utilisation models have highlighted the role of social networks and support more broadly. Most notably, the Network-Episode Model (NEM) is a theory of health service utilisation that emphasises the critical and dynamic role that social support resources and social interaction with network members play in the process of decision making (Pescosolido 1991).

The NEM suggests that decisions regarding health service utilisation are shaped by the attitudes and actions of friends and family members. The NEM recognizes that individuals often confer with members of their networks when making health decisions, and that the emotional support, advice, and information they receive from these people can have a significant and measureable influence on their health behaviors and utilisation choices. Often, supportive networks contribute to early entry into health services and compliance with treatment plans (Perry and Pescosolido 2010). Alternatively, having a very strong social safety net could lead to overregulation and the perception that formal health services are unnecessary (Durkheim 1951). Likewise, networks characterized by negative attitudes toward health professionals or medical care could provide well-intentioned support that “pushes” individuals away from formal (i.e. professional) health care services (Pescosolido 1991).

Identifying the linkages between social support and health services utilisation is complex, in part because the direction of the effect may depend on the composition and “content” (i.e. the attitudes, advice, experiences) of the network that is providing support (Perry and Pescosolido 2010). Additionally, some research finds that health needs moderate the impact of social support such that the combination of high need and low social support increases use of ambulatory services (Kouzis and Eaton 1998, Penning 1995). This seems to suggest that supportive networks buffer either actual or perceived need for health services, but much less is known about how social support affects use of preventative services, which are not need-dependent and are more likely to be influenced by access issues (Wyn et al. 2004). Further, research of this kind has never been conducted using a sample of low-income African American women, so it is unclear how social support from family and friends influence preventative care help-seeking decisions. Specifically, social support may be of particular importance among those with limited resources, who may be disproportionately likely to rely on lay members of their social network to fill gaps in formal help-seeking. Understanding the influence of social support for this at-risk population is needed to provide insight into pathways to regular preventative health services utilisation and early detection of disease among African American women, potentially contributing to improvements in the health and longevity of members of this minority group.

Religiosity

African Americans, especially women, consistently report higher levels of religious involvement than other ethnic groups, and religion has been called the “cornerstone” of African American communities (Chandler 2010, Watlington and Murphy 2006). High levels of church attendance enhance the solidarity of these communities, and the church holds an important place as a social and cultural institution (Blank et al. 2002, Chandler 2010). Consequently, past research has examined the effects of spiritual beliefs on African Americans’ use of health services (Ward et al. 2009, Kinney et al. 2002, Mitchell et al. 2002). Though findings are mixed, they generally indicate that more religious African American women tend to use preventative and screening services less frequently, relying more on spiritual beliefs than formal medical services to manage their health (Kinney et al. 2002, Mitchell et al. 2002). The results of this research, coupled with the well-established importance of religion and spirituality in African American communities, demonstrate the necessity of considering religiosity when examining patterns of utilisation among African American women.

In sum, though the existing empirical research has linked culturally-specific factors to African American women’s use of certain types of health services, further research is needed to examine how these factors relate specifically to preventative care utilisation(Chandler 2010, LeVeist et al. 2003). This lack of research is especially evident as it relates to vulnerable populations, such as low-income women, who are among those most in need of preventative services and least likely to use them. In response to these gaps in the literature, this research explores self-reported barriers to utilisation among low-income African American women, and investigates the impact of cultural and social factors on one type of preventative health service – having a physical exam in the past year. Specifically, we examine African American women’s likelihood of having a physical exam as a function of 1) access and economic factors; 2) racial experiences and attitudes; 3) social support from friends and family; and 4) religiosity.

Methods

Sample

The data used in this research are from the first wave of the B-WISE (Black Women in a Study of Epidemics) Project. This data was collected between 2008 and 2009 in an urban setting as part of an ongoing project evaluating the health consequences of substance use among African American women. In addition to the community sample used in these analyses, the B-WISE Project includes a sample of African American female probationers and a sample of incarcerated African American women. Drug users were over sampled due to higher rates of drug use among women in the criminal justice system. This stratified sampling technique ensured that approximately 100 of the women in the community sample had used illicit drugs in the year prior to their recruitment.

The community sample was recruited through advertisements in local newspapers and flyers posted in areas with high percentages of African American residents. Women interested in participating called the study offices and were screened by interviewers to determine eligibility. To participate, respondents had to be 18 years or older, self-identify as African American and female, and not be under supervision of the criminal justice system. Eligible women were interviewed by trained African American female interviewers in private locations, including meeting rooms at public libraries and the study office. All data were collected with computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) to reduce response and data entry error. Study participants were compensated for their time, earning $20 for the baseline interview with additional incentives up to $40 for completing optional drug and disease testing.

The community sample used for these analyses includes 205 African American women, with an average age of 36.55 years. Most of the women are unmarried (86.82%). On average, respondents have 12.74 years of education and the mean household income is $20,760. African American women in the sample are significantly less likely to be married than those in the targeted zip codes (13.17% compared to 29.00%; Z=4.57; 2000 Census), but are otherwise representative of the population sampled. Though this sample is not representative of African American women within the U.S. generally, it does mirror the demographics of low-income, urban African American women in the United States.

Measures

Barriers to healthcare

Respondents were asked to report reasons why they “didn’t get health care or even an annual physical exam during the past year”. Thirty potential responses were presented and participants selected all that applied. Barriers reported with the greatest frequency and those which related directly to independent variables examined in the quantitative analysis were selected. Their frequencies were reported in Table 2 both for descriptive purposes and to assess the validity of the regression results.

Table 2.

Perceived Barriers to Health Care Identified by Respondents (B-WISE Community Sample, N=205)

| Barrier | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| No barriers to health care | 78 | 38.05 |

|

| ||

| No insurance coverage | 60 | 29.27 |

| Costs too much | 42 | 20.49 |

| Had to wait too long for an appointment | 17 | 8.29 |

| Didn’t have a way to get there | 15 | 7.32 |

| Couldn’t take time off work | 10 | 4.88 |

| Don’t trust doctors | 6 | 2.93 |

| Fear of being refused health care | 3 | 1.46 |

| Fear of being treated rudely | 2 | 0.98 |

| Couldn’t get tX by an A.A. physician | 1 | 0.49 |

| Fear of racial discrimination | 0 | 0.00 |

Note: Participants could cite multiple barriers

Sources of health information

Respondents were also asked to report where they received “information about how to prevent illness and improve health” in the past year. Fourteen potential sources were presented and participants selected all that applied. Table 3 shows the number of participants who identify family, friends and physicians as sources of health information – presented to compliment the interpretation of regression results.

Table 3.

Past Year Sources of Health Information (B-WISE Community Sample, N=205)

| Source | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Doctor/Health Care Provider | 149 | 72.68 |

| Family | 121 | 59.02 |

| Friends | 93 | 45.37 |

Note: Participants could cite multiple sources.

Preventative care usage

A dummy variable is used, coded 1 if respondents had received a physical in the past year and 0 if they did not. Other measures of preventative care utilisation (e.g. mammogram, eye exam) were excluded due to missing data.

Social demographic variables

A variable for age is coded in years. A dummy variable for marital status is coded 1 if the respondent is married, and 0 for other potential marital statuses. Education is coded in years, while household income is coded in thousands of dollars, to the midpoint.1 A control variable for past year illicit drug use is also introduced, because of the potential bias from the high percentage of drug using respondents. Drug use is a dichotomous variable, coded 1 if the respondent has used illicit drugs in the past year, not including marijuana, and coded 0 if they have not. Marijuana was not included as an illicit drug due to the normative nature of marijuana use among African Americans (Wei et al. 2004, Golub and Johnson 2001).

Access

Three variables that indicate respondents’ access to health services are used. Two dummy variables for insurance are included: private insurance is coded 1 if the respondent has private insurance and public insurance is coded 1 if the respondent has public insurance. The excluded reference category is no insurance. The third access variable, called usual doctor, is a dummy variable coded 1 if the respondent has a usual doctor and 0 if they do not.

Racial attitudes and experiences

Three variables are used to measure experiences and attitudes that are likely to be culturally-specific. Trust in physician is measured using a scale developed by Anderson and Dedrick (1990). The 11 question scale was created to assess respondents’ interpersonal trust in their physician (α=.84). Anderson and Dedrick’s scale does not measure whether the respondent believes in the physician’s ability to positively affect their health, but rather considers the ongoing relationship between physician and patient and the respondent’s belief that the physician’s words and behavior are in their best interests. Response categories range from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”.

Racist life events are measured using the schedule of racist events developed by Landrine and Klonoff (1996). This additive 18-item scale asks respondents to report the frequency of various types of racial discrimination they have experienced during their lifetime (α=.92). Examples include being treated unfairly by teachers and colleagues and being suspected of wrongdoing because of their race (Landrine and Klonoff 1996). Response categories range from 1 (“never happened”) to 7 (“almost all of the time”).

Cultural mistrust is measured using the cultural mistrust inventory created by Terrell and Terrell (1996). It was developed to assess the degree to which African Americans mistrust whites in interpersonal and social contexts. Response categories range from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”. Possible scores range from 18 to 98, with higher scores indicating more mistrust of whites (α=.73).

Social support

Four variables are used to measure respondents’ social support. Two subscales developed by Zimet and colleagues are used to measure perceived social support from family and perceived social support from friends (1988; α=.94 and α=.94, respectively). Both scales include four items which assess the degree to which respondents perceive family and friends support them as they deal with everyday decisions and problems. Questions include such items as “my family/friends are willing to help me make decisions” and “I can talk about my problems with my family/friends”. Scores are determined by calculating the mean of participants’ responses, which range from 1 to 7, with higher scores corresponding to a high level of support (Zimet et al. 1988).

Religiosity

Two variables were also used to measure respondents’ involvement in faith activities and religious well-being. Church attendance is a count variable that indicates the number of days participants attended church in the past year. Responses range from not attending church to attending church weekly. Religious well-being is a 24-item additive scale measuring one’s sense of well-being in relation to God (Paloutzian and Ellison 1982). Response categories range from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree” (α=.88).

Analyses

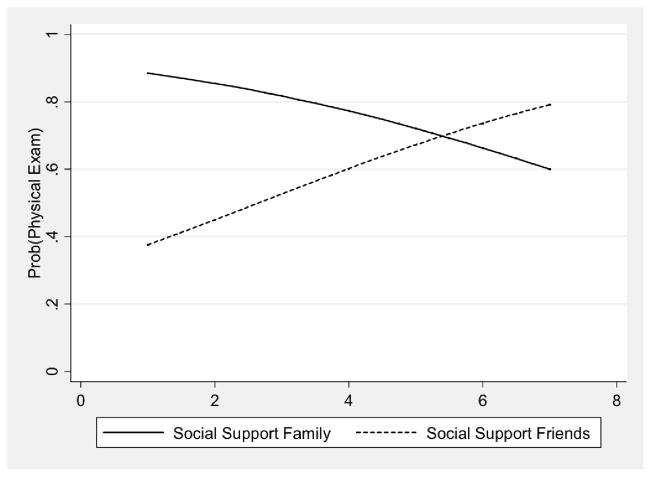

These analyses explore relationships between use of preventative health services and insurance status, physician trust, racist life events, cultural mistrust, social support and religiosity. First, frequency distributions on respondent-identified barriers to healthcare and sources of health information are presented. Binary logistic regression using Stata’s logit command is used to identify predictors of preventative care usage. Model 1 regresses annual physical on social demographic variables, including the drug use control variable. Model 2 includes variables measuring access to health services, cultural mistrust and physician trust, social support, and religiosity. Finally, the full model, Model 3 is presented with all variables including both racism and cultural mistrust. Figures of predicted probabilities are presented to facilitate interpretation of the effects of social support.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the dependent and independent variables are presented in Table 1. Approximately 66.83% of the African American women sampled report having had a physical exam in the past year. With regard to insurance status, 34.68% of women report having private insurance, while 32.68% report having public insurance. Results also indicate that 53.17% of the women have a regular doctor that they typically see for health matters.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the B-WISE Community Sample (N=205)

| % | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past year physical exam | 66.83 | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 36.55 | 14.22 | 18.00–68.00 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently married | 13.17 | |||

| Div/wid/sep | 23.41 | |||

| Never married | 63.41 | |||

| Education (years) | 12.74 | 2.25 | 3.00–20.00 | |

| Household income (thousands) | 20.76 | 21.23 | 2.50–87.50 | |

| Controls | 15.04 | 12.31 | 0.00–67.00 | |

| Drug use (not marijuana, past year) | 20.98 | |||

| Access | ||||

| No insurance | 34.63 | |||

| Public insurance | 32.68 | |||

| Private insurance | 34.68 | |||

| Usual doctor | 53.17 | |||

| Culture & Health Beliefs | ||||

| Trust physician | 41.14 | 6.53 | 25.00–55.00 | |

| Cultural mistrust | 44.69 | 10.27 | 18.00–93.00 | |

| Racist life events | 31.92 | 12.31 | 17.00–84.00 | |

| Social Safety Net | ||||

| Social support – family | 5.39 | 1.61 | 1.00–7.00 | |

| Social support – friends | 5.41 | 1.48 | 1.00–7.00 | |

| Church attendance (days, past year) | 25.74 | 20.68 | 0.00–52.00 | |

| Religious well-being | 63.80 | 7.71 | 31.00–72.00 | |

When considering racial attitudes and experiences, the mean level of trust in physician is 41.14, indicating a medium level of trust as measured by Anderson and Dedrick’s scale (1990). With regard to cultural mistrust and racist life events, the sample means are 44.69 and 31.92 respectively, indicating a medium level of cultural mistrust and racist life experiences as measured by the scales used. Further, the mean level of social support from family and friends is moderate to high (5.39 and 5.41 respectively). The mean of past year church attendance is 25.74 days, and the mean for religious well-being is high at 63.80.

Table 2 presents the barriers to health care utilisation identified by respondents. Results indicate that 29.27% of those sampled identify lack of insurance as a barrier to obtaining health services, with 20.49% stating that cost is a deterrent. Additionally, 4.88% of respondents identify an inability to take time off work as a barrier to getting health care, while 8.29% of the women believe the long wait for an appointment reduces their use of health care. Only 2.93% of women sampled identify a lack of trust in physicians as preventing their utilisation of health services. Additionally, less than 1.00% of women identify a fear of being treated rudely as a barrier to health care and only 1.46% agree that fear of being refused health care deters their use of services. Importantly, results indicate that no respondents identify a fear of racial discrimination as inhibiting their use of health services, and only 1 respondent indicates that she did not use services because she could not get treatment from an African American physician.

Table 3 presents sources of health information in the past year. According to these results, 59.02% of the African American women sampled report turning to their family members for health information, while 45.37% consult friends. The majority of respondents report a physician or other health care provider as a source of health information in the past year (72.68%). Overall these results indicate that many of the African American women sampled rely on family and friends to inform choices regarding their health. This provides initial support for the Network Episode Model.

Table 4 shows the results of the logistic regression models examining the effect of demographic characteristics, access to health services, racial attitudes and experiences, social support, and religiosity on past year physical exam. Model 1 includes only basic demographic variables and the drug use control variable. None of the variables achieve significance and, based on the pseudo R-squared, explain very little of the variance surrounding the dependent variable. Model 2 includes all the variables of the full model, with the exception of the racism measure. This model examines both the impact of factors identified using Andersen’s Health Behavior model and the Network Episode Model, as well as the measures for trust in physician and cultural mistrust. According to this model, respondents with public insurance have higher odds than those without insurance to have a physical in the past year – lending initial support to the economic component of health care utilisation highlighted in Andersen’s theory (OR=5.53). The odds of having a physical in the past year are also increased by a factor of 2.86 for respondents who have a regular doctor relative to those who do not, holding covariates constant. Model 2 also lends support to the Network Episode Model, as it suggests that social support factors shape health care utilisation.2 For each unit increase in perceived family social support, the odds of having a past year physical are decreased by a factor of 0.71. In contrast, increasing perceived social support from friends is significantly associated with an increase in the odds of having a physical (OR=1.36). Finally, education is significant and positively related to the odds of having a physical in Model 2 (OR=1.24). Neither variables measuring religiosity nor those measuring culture or health beliefs achieve significance.3

Table 4.

Logistic Regression of Past Year Physical on Selected Demographic, Access, Culture, and Safety Net Variables (BWISE Community Sample, N=205)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.01) | 0.99 (0.01) | 0.99 (0.01) |

| HH income ($K) | 0.99 (0.01) | 0.98 (0.01) | 0.98 (0.01) |

| Education (years) | 1.14 (0.08) | 1.24 (0.11)* | 1.21 (0.11)* |

| Controls | |||

| Drug use1 (past year) | 0.64 (0.24) | 1.14 (0.51) | 1.22 (0.56) |

| Access | |||

| Private insurance | — | 2.03 (0.92) | 2.01 (0.92) |

| Public insurance | — | 5.53 (2.58)*** | 5.79 (2.75)*** |

| Usual doctor | — | 2.86 (1/08)** | 2.72 (1.04)** |

| Culture & Health Beliefs | |||

| Trust physician | — | 1.01 (0.28) | 1.03 (0.03) |

| Cultural mistrust | — | 0.97 (0.02) | 0.96 (0.02)* |

|

| |||

| Racist life events2 | — | — | 1.04 (0.02)* |

|

| |||

| Social Safety Net | |||

| Currently married3 | 1.61 (0.88) | 1.68 (0.01) | |

| Social support - family | — | 0.71 (0.10)* | 0.72 (0.10)* |

| Social support - friends | — | 1.36 (0.19)* | 1.40 (0.20)* |

| Church attendance | — | 1.01 (0.01) | 1.02 (0.01) |

| Religious well-being | — | 1.02 (0.03) | 1.00 (0.03) |

|

| |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0240 | 0.1727 | 0.1933 |

| LR X2 | 6.25 | 44.99*** | 50.36*** |

Odds ratios presented, standard errors in parentheses.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Reference is no drug use

Suppressor variable

Reference is never married/widowed/divorced

Note: Various interaction terms were tested but not found to be significant (results available on request).

Model 3, the full regression model, includes all the variables of interest – including a measure for racist life events. As in Model 2, having more education, public insurance, and a usual doctor are associated with a greater likelihood of having a physical exam. The social support measures also remain significant and of similar magnitude. Though cultural mistrust was not significant in Model 2, when a measure for racist life events is added in Model 3, the effect becomes significant. For each unit increase in cultural mistrust, the odds of having a past year physical are decreased by a factor of 0.96, holding covariates constant. The effect of racist life events, conversely, appears to be significant but in an unexpected direction. Post hoc analyses suggest that racist life events have a suppressor effect on cultural mistrust. By definition, suppressor variables have little or no correlation to the dependent variable, but improve model fit through their relationship to one or more other predictors (Thompson and Levine 1997). As the correlation matrix in Table 5 suggests, cultural mistrust and racism are significantly correlated (r=0.31), as are mistrust and the dependent variable, past year physical exam (r=−0.15). However, racism is not significantly correlated to the dependent variable, and fails to achieve significance when included in the regression model without the mistrust measure.4 Though including two collinear variables in regression equations is often problematic, in the case of suppressor variables, their inclusion is essential and serves to control for or “suppress” some of the random variance in the predictor with which they are correlated. In this case, the effect of cultural mistrust can be considered unbiased and meaningful, while the effect of racist life events is uninterpretable.

Table 5.

Correlation Matrix of Dependent Variable, Cultural Mistrust, and Racist Life Events Suppressor

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Physical Exam, Past Year | 1.00 | ||

| 2 Cultural Mistrust | −0.15* | 1.00 | |

| 3 Racist Life Events | 0.08 | 0.31*** | 1.00 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Figure 1 graphically presents the predicted probability of past year physical exam as a function of social support from family and friends. According to this figure, as social support from family increases, the predicted probability of having a past year physical decreases. However, as social support from friends increases, the predicted probability of having a past year physical increases.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of Past Year Physical Exam as a Function of Social Support from Family and Social Support from Friends

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the use of preventative health services among low-income African American women is influenced by a variety of demographic, social, and cultural factors. While access and demographic factors have clear and measureable impacts on utilisation, racial experiences and attitudes are also powerful forces in the lives of these women. Findings also highlight the importance of social support from family and friends as low-income African American women make decisions about help-seeking. Broadly, the results of this study reveal the significant impact that social and cultural factors have on the health decisions of African American women, underscoring the need for their inclusion in models of health service utilisation among this population.

The importance of access

Our findings provide support for the role of access barriers identified by Andersen’s Health Behavior Model (1968). Consistent with previous research, African American women with public insurance were more likely to use preventative care services when compared to the uninsured (Patel et al. 2010, DeVoe et al. 2003). This indicates that access to affordable preventative services constitutes a barrier for some women. These findings align with factors that the respondents themselves identified, lending further support to the multivariate models and underscoring the importance of access in navigating the American healthcare system.

Also consistent with previous research, our results indicate that African American women with a usual doctor are more likely to utilise preventative care services (Schueler et al. 2008, DeVoe et al. 2003, Ettner 1999). Respondents with a usual physician may feel more comfortable with a doctor who is familiar with their health history and with whom they have an established rapport. This may increase a patient’s sense of their physician’s competency, resulting in more consistent utilisation. Additionally, having a usual doctor may mean that basic tasks like appointment scheduling are easier as patients do not have to search for a physician and already know who to contact to arrange care. In all, this finding has important implications for African American women, as past research indicates that those with a usual source of care tend to have more consistent rates of utilisation, experience fewer hospitalisations, and have lower health costs (Ettner 1999, Sox et al. 1998).

The influence of racial experiences and attitudes

A wealth of literature in the social sciences suggests that racial discrimination affects health outcomes and behaviors (Williams and Sternthal 2010, Williams and Mohammed 2009). Therefore, an important aim of this research was to assess the impact of racial experiences and attitudes that have previously been connected to racial health disparities, but that have been rarely examined as predictors of preventative care services. Findings indicate that as cultural mistrust increases, the predicted use of preventative health services decreases. While only one respondent identified not having an African American caregiver as a barrier to health care, these results suggest that feelings of cultural mistrust expressed by respondents may be projected onto medical institutions, influencing utilisation decisions.

That African Americans experience cultural mistrust that is directed toward medical institutions is consistent with previous research. The “shadow” of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, denial of treatment and services in the pre-Civil Rights Era, and lingering inequalities in access to and treatment within medical institutions into the present, shape perceptions among African Americans about the health care system (Chandler 2010). That these institutions are dominated by white providers and administrators makes overcoming these negative perceptions even more difficult (LaVeist et al. 2003). The results of this study lend further support to these ideas, and demonstrate the important impact that cultural mistrust and racist life experiences can have on service utilisation.

The social nature of help-seeking

Another objective of this study was to assess the degree to which social support and religiosity, which may have special relevance for low-income African American women, influence decisions to use preventative health care. With regard to familial social support, results indicate that women with high levels of social support are less likely to seek out preventative care. While the findings regarding the impact of family social support on health service utilisation are mixed, the results presented here are likely due to the particular type of health care studied; preventative care. Past research has suggested that women with high levels of familial support may be less likely to seek out preventative care because they perceive their needs for general health maintaining advice are being met by family members (Salloway and Dillon 1973). This aligns with what respondents themselves indicated, since 59.02% reported they turned to family members for health information in the past year (see Table 3). Additional research on pathways to care is needed to verify whether African American women are substituting or delaying preventative services by relying on lay advice from family – or if they are being directly discouraged from using such services.

When considering social support from friendship networks, our findings reveal that as social support from friends increases, so too does the probability of utilising preventative care services. These conflicting results on social support from friends and family are unexpected, and warrant further research to identify the underlying causal mechanisms at work. Though no definitive explanations for these findings can be identified using these data, we speculate that differences in the socio-demographic make-up of family and friendship social networks may partially explain these findings. It may be, for example, that compared to family networks, friendship networks are younger and more racially heterogeneous, on average. Since most racial groups and younger people have higher rates of preventative health services utilisation than those who are African American and older, friends may be more likely than family members to have used preventative health services themselves (Chandler 2010, Neighbors and Jackson 1984). Consequently, the women in the study may be exposed to vicarious experiences with the medical system through their friendship networks. These indirect experiences through others who use services have been linked to one’s own higher usage of services (Alvidrez 1999). In any case, additional research is needed to provide a more nuanced explanation of how social support, and networks more broadly, shape the utilisation of preventative care services.

Despite the importance of social support, having a church community did not emerge as a significant predictor of preventative care usage. This is surprising, as previous research has emphasised the importance of religiosity in African American women’s lives (Chandler 2010, Watlington and Murphy 2006). For those dealing with a serious physical illness or debilitating psychological distress, research has found that spiritual beliefs are an important coping resource associated with greater functioning and quality of life (Tarakeshwar et al. 2006). However, when considering preventative health care, religiosity does not emerge as a significant predictor, suggesting that preventative care does not provoke the type of spiritual concern and deliberation that does other types of health care, such as end of life care (Wicher and Meeker 2012).

Limitations

This research has several limitations that merit discussion. The sample of African American women used in this research is not nationally representative, and therefore the findings cannot be extended to all African American women. Additionally, the high percentage of drug users among the data used for these analyses also prohibits the generalisability of findings. That said, findings can reasonably be extended to African American women with low socio-economic status. Further, with regard to drug use, it is important to also note that all major findings hold when drug use is controlled for in the analyses. Despite the unique sampling procedures used in the B-WISE, the results of this study are suggestive of patterns of preventative care utilisation among low-income African American women, and should be further tested using a nationally representative sample. Because these women exist at the intersection of disadvantaged racial, gender, and socioeconomic statuses, research investigating this group’s unique barriers to health care utilisation and good health, more broadly, has public health significance and constitutes an important contribution.

Future research

In all, the results presented here represent an important initial step toward understanding the use of preventative health services among low-income African American women. As the findings demonstrate, a consideration of social and cultural factors that are present in African American women’s lives is critical for the study of preventative care utilisation behaviors. Though sociologists have long recognised that health behaviors are influenced by these factors, this research extends the existing literature by testing a more comprehensive model of culturally-specific factors on an understudied type of health service utilisation, preventative care (Kleinman 1980, Olafsdottir and Pescosolido 2009). In addition, by focusing on an underserved and under-researched population, this work also provides some basis for understanding how the effect of such influences can vary depending on the type of health services examined.

This research demonstrates that both cultural mistrust and racist life events have substantial influences on having an annual physical. However, more research is necessary to understand the psychosocial processes and other mechanisms through which sentiments of cultural mistrust and racist life events deter or promote decisions to utilise preventative health services. This research makes clear that the pathways between such experiences and use of preventative health care are not simple or direct, and warrant further investigation. Likewise, the results of this research broadly indicate that the social networks in which African American women are embedded matter in meaningful ways, providing robust support for the Network Episode Model. Given the findings, it appears that support from friends may be a key resource for women that receive a yearly physical. Future research examining how to more effectively build and mobilize network resources to encourage help-seeking may be particularly fruitful. Research focusing on the structure, strength, and specific content of such network ties is required to fully understand the nature of their influence on health decisions (Horwitz 1978, Perry & Pescosolido 2010, Pescosolido 1991).

Finally, while lacking insurance and a usual physician remain predictable correlates of not receiving an annual physical, the impact of such access issues on vulnerable populations will need to be re-evaluated as the United States moves to incorporate a public option for health insurance. While greater access is likely to improve population health, it remains to be seen how such changes will affect the help-seeking behaviors of vulnerable populations, for whom affordability is but one of many factors that shape preventative health care decisions. According to our findings, as traditional predictors become less relevant, it will be critical to explore how variations in discrimination experiences and social relationships across gender and racial groups drive patterns of utilisation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA22967, PI: Oser; K01-DA021309, PI: Oser).

Footnotes

Income was initially reported as a range, but coded to the midpoint (e.g. $0 – $4999 = 2.5).

Additional social network and support measures were tested in preliminary analyses but did not improve model fit. Items in the social support scales were tested individually to gain insight into which features of support (i.e. instrumental, emotional) drive this relationship to preventative care usage. Individual items did not achieve significance, suggesting an effect of global perceptions of available support rather than of actual exchanges or interactions (results on request). The most parsimonious model was presented.

In addition to testing additional measures of religiosity not presented here, the included religiosity measures were tested with the social support measures excluded. These measures remained non-significant suggesting no problems with confounding or collinearity between these variables.

Interactions of cultural mistrust and racist life events were also tested, but were not significant.

References

- Alvidrez J. Ethnic variation in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health. 1999;35(6):515–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R. A Behavioral Model of Families’ Use of Health Services. Chicago: Center for Health Administration Studies; 1968. Research Series No. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L, Dedrick R. Development of the trust in physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient-physician relationships. Psychological Reports. 1990;67:1091–100. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3f.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell D, Martinez M, Gentleman J, Sanmartin C, et al. Socioeconomic status and utilization of health care services in Canada and the United States: findings from a binational health survey. Medical Care. 2009;47(11):1136–46. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181adcbe9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank M, Mahmood M, Fox J, Guterbock T. Alternative mental health services: the role of the black church in the south. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1668–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. African American resiliency: examining racial socialization and social support as protective factors. Journal of Black Psychology. 2008;34(1):32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D. The underutilization of health services in the black community: an examination of causes and effects. Journal of Black Studies. 2010;40(5):915–31. [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe J, Fryer G, Phillips R, Green L. Receipt of preventative care among adults: insurance status and usual source of care. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):786–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe J, Wallace L, Pandhi N, Solotaroff R, et al. Comprehending care in a medical home: a usual source of care and patient perceptions about healthcare communication. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2008;21(5):441–50. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.080054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B, Levav I, Shrout P, Schwartz S, et al. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;21:946–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide. New York: Free Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Ettner S. The relationship between continuity of care and health behaviors of patients: does having a usual physician make a difference? Medical Care. 1999;37(6):547–55. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: A review. Cancer Epidemiolog, y Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17(11):2913–23. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson B. The risk of marijuana as the drug of choice among youthful adult arrestees. Report for US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice. 2001 Report no. NCJ 187490. Available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/187490.pdf.

- Higginbottom G. ‘Pressure of life’: Ethnicity as a mediating factor in mid-life and older peoples’ experience of high blood pressure. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2006;28(5):583–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz A. Family, kin, and friend networks in psychiatric help-seeking. Social Science and Medicine. 1978;12:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulksy JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(4):711–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney A, Emery G, Dudley W, Croyle R. Screening behaviors among African American women at high risk for breast cancer: do beliefs about god matter? Oncology Nursing Forum. 2002;29(5):835–43. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.835-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and Psychiatry. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff E, Landrine H. Cross-validation of the schedule of racist events. The Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25(2):231–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzis A, Eaton W. Absense of social networks, social support, and health service utilization. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28(6):1301–10. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H, Hoyert D, Xu J, Murphy S. National Vital Statistcs Reports. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Deaths: final data for 2005; p. 56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff E. The schedule of racist events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22(2):144–68. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist T, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones K. The association of doctor-patient race concordance with health service utilization. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2003;24:312–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Ayers S, Kronenfeld J. The association between perceived provider discrimination, healthcare utilization and health status in racial and ethnic minorities. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(3):330–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciosek M, Coffield A, Flottemesch T, Edwards N, et al. Greater use of preventive services in U.S. health care could save lives at little or no cost. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1656–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J, Lannin D, Matthews H, Swanson M. Religious beliefs and breast cancer screening. Journal of Women’s Health. 2002;11(10):907–15. doi: 10.1089/154099902762203740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff J. Neighborhood mechanisms and the spatial dynamics of birth weight. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108(5):976–1017. doi: 10.1086/374405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors H, Jackson J. The use of informal and formal help: four patters of illness behavior in the black community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1984;12(6):629–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00922616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V, Peschard K. Anthropology, inequality, and disease: a review. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2003;32:447–474. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda V, Bergstresser S. Gender, race-ethnicity, and psychosocial barriers to mental health care: An examination of perceptions and attitudes among adults reporting unmet need. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49(3):317–34. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsdottir S, Pescosolido B. Drawing the line: the cultural cartography of utilization recommendations for mental health problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(2):228–44. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian R, Ellison C. Loneliness, spiritual well-being and the quality of life. In: Peplau L, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1982. pp. 224–37. [Google Scholar]

- Patel N, Bae S, Singh K. Association between utilization of preventive services and health insurance status: findings from the 2008 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Ethnicity & Disease. 2010;20(2):142–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning M. Health, social support, and the utilization of health services among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B. 1995;50:S330–39. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.5.s330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Harp K, Oser C. Racial and gender discrimination in the stress process: implications for African American women’s health and wellbeing. Sociological Perspectives. 2013;56(1):25–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Pescosolido B. Functional specificity in discussion networks: the influence of general and problem-specific networks on health outcomes. Social Networks. 2010;32(4):345–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B. illness careers and network ties: a conceptual model of utilization and compliance. In: Albrecht G, Levy J, editors. Advances in Medical Sociology. Greenwich: JAI Press; 1991. pp. 161–84. [Google Scholar]

- Prus S. Age, SES, and health: A population level analysis of health inequalities over the lifecourse. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2007;29(2):275–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloway J, Dillon P. A comparison of family networks and friend networks in health care utilization. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1973;4(1):131–42. [Google Scholar]

- Schueler K, Chu P, Smith-Bindman R. Factors associated with mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17(9):1477–98. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers V, Fagan P, Jones D, Klein W, et al. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(5):953–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenson D, Adams M, Bolen J, Wooten K, et al. Developing an integrated strategy to reduce ethnic and racial disparities in the delivery of clinical preventive services for older Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(8):44–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snipes S, Wilson D, Esparza A, Jones L. A general overview of cancer in the United States: incidence and mortality burden among African Americans. In: Braithwaite R, Taylor S, Treadwell H, editors. Health Issues in the Black Community. 3. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. pp. 259–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sox C, Swartz K, Burstin H, Brennan T. Insurance or a regular physician: which is the most powerful predictor of health care? American Journal of Public Health. 2008;88(3):364–70. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T, Brown M, Funnell M, Anderson R. Social support, quality of life, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2008;34(2):266–76. doi: 10.1177/0145721708315680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Vanderwerker L, Paulk E, Pearce M, et al. Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(3):646–57. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell F, Terrell S. The cultural mistrust inventory: development, findings, and implications. In: Jones R, editor. Handbook of Tests and Measurements for Black Populations. Virginia: Cobb & Henry Publishers; 1996. pp. 321–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(S):S41–53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson F, Levine D. Examples of easily explainable suppressor variables in multiple regression research. Multiple Lines Regression Viewpoints. 1997;24:11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Todorova L, Falcón L, Lincoln A, Price L. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress, and health. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010;32(6):843–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E, Clark L, Heidrich S. African American women’s beliefs, coping behaviors, and barriers to seeking mental health services. Quantitative Health Research. 2009;19(11):1589–1601. doi: 10.1177/1049732309350686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watlington C, Murphy C. The roles of religion and spirituality among African American survivors of domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(7):837–57. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei E, Loeber R, White H. Teasing apart the development associations between alcohol and marijuana use and violence. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2004;20(2):166–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wicher C, Meeker M. What influences African American end-of-life preferences? Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2012;23(1):28–58. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Mohammed S. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: sociological contributions. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(S):S15–27. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright E, Perry B. Medical sociology and health services research: past accomplishments and future policy changes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(S):S107–19. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyn R, Ojeda V, Ranji U, Salganicoff A. Report. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menio Park: 2004. Racial and ethnic disparities in women’s health coverage and access to care: findings from the 2001 Kaiser women’s health survey. [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Matthews S, Hillemeier M. Effect of health care system distrust on breast and cervical cancer screening in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(7):1297–1305. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G, Dahlem N, Zimet S, Farley G. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas S, Fleishman J. Self-rated mental health and racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use. Medical Care. 2008;46(9):915–23. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817919e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]