Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is characterized by aggressive behavior with a propensity for metastasis and recurrence. Here we report a comprehensive analysis of the molecular and clinical features of HNSCC that govern patient survival. We find that TP53 mutation is frequently accompanied by loss of chromosome 3p, and that the combination of both events associates with a surprising decrease in survival rates (1.9 years versus >5 years for TP53 mutation alone). The TP53-3p interaction is specific to chromosome 3p, rather than a consequence of global genome instability, and validates in HNSCC and pan-cancer cohorts. In Human Papilloma Virus positive (HPV+) tumors, in which HPV inactivates TP53, 3p deletion is also common and associates with poor outcomes. The TP53-3p event is modified by mir-548k expression which decreases survival even further, while it is mutually exclusive with mutations to RAS signaling. Together, the identified markers underscore the molecular heterogeneity of HNSCC and enable a new multi-tiered classification of this disease.

INTRODUCTION

It is increasingly appreciated that the diversity of clinical outcomes in HNSCC is likely a reflection of the molecular heterogeneity of the tumor population1,2,3. Previous studies have led to the identification of a variety of genes and other molecular features for stratifying HNSCC tumors, such as efforts to cluster gene expression profiles to define subtypes4,5,6,7,8. To comprehensively define this heterogeneity of common tumor types including HNSCC, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project has generated multi-tiered molecular profiles for over 7000 patient tumors, providing an unprecedented opportunity to study the complex interrelations among fundamentally different types of molecular events and clinical outcomes such as patient survival.

Here we have built on the infrastructure established by TCGA to systematically and transparently unravel these complex relationships for HNSCC. To this effect, we obtained all available molecular and clinical data from TCGA (unpublished, TCGA HNSCC working group) as of the January 15, 2014 Firehose run and have documented all data-processing and analysis in a series of IPython Notebooks9 (Methods, Supplementary Table 1). Five tiers of data – somatic mutations, chromosomal aberrations, mRNA expression, microRNA expression, and clinical variables – were analyzed for a total of 378 HNSCC patients resulting in measurements of over 34,000 molecular or clinical values for each patient (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Because old age and HPV status are associated with distinct molecular profiles and clinical outcomes1 (Supplementary Fig. 2), we focused analysis on the 250 patients under 85 years of age with HPV– tumors and complete molecular profiles.

RESULTS

Identification of prognostic events in HNSCC

We first sought to distill this multi-tiered, genome-wide dataset into a set of informative molecular and clinical events with potential relevance to cancer. First, individual somatic mutations and mRNA expression levels were integrated with knowledge of human molecular pathways to define aggregate ‘pathway-level events’ (Supplementary Fig. 1b-e, Methods). Second, both individual and pathway events were filtered to select those that occur at high frequency (somatic mutations, chromosomal aberrations) or differential expression (mRNA and microRNA levels) in tumor versus normal tissue. The result of this analysis was a pool of 878 total events combined over all five tiers of data (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

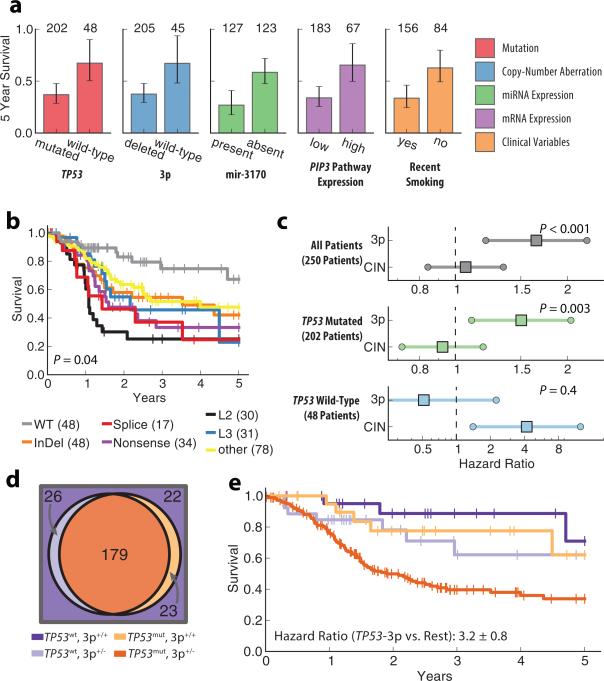

Next, we screened for individual events within each data type that are strongly predictive of survival, identifying 82 prognostic events out of the 878 (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 2). Among somatic mutation events, TP53 mutation was most strongly predictive overall, resulting in poor prognosis (Hazard Ratio 2.9 ±0.8, Benjamini Hochberg corrected P < 0.01). As has been observed previously, survival outcomes were dependent on the TP53 protein domain affected by the mutation or its predicted functional status10 (Fig. 1b). However, we found that patients with mutations predicted as non-disruptive of function nonetheless had worse prognosis than patients with wild-type TP53 (Hazard Ratio 2.2±0.7, P = 0.03). Among copy-number alterations, the most significant survival association was with heterozygous chromosomal deletions on the 3p arm which also led to very poor prognosis (Fig. 1a, Hazard Ratio 3.5±1.1, Benjamini Hochberg corrected P = 0.002). Further analysis of chromosome 3p revealed that many patients have a deletion spanning a large fraction of the arm with increasing frequency of deletion approaching a fragile site in the 3p14.2 region11 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Although general chromosomal instability (CIN) as well as deletion of many individual chromosomal regions have previously been implicated as diagnostic1,12 and prognostic7,13,14,15 markers, we find that the 3p event in particular was responsible for the majority of the impact on survival when compared with global rates of gene deletion (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Prognostic effects and co-occurrence of TP53 and 3p.

a, Five-year survival (error bars indicate 95% CI) for the most significant events of each category (colors). Numbers above bars represent number of patients with each event. b, Comparison of 5-year survival for patients with different types of non-silent TP53 mutations verses wild-type patients. L2 and L3 represent TP53 binding domains. Numbers in parentheses represent number of patients with a given mutation, patients with multiple TP53 mutations are represented multiple times in this plot. P-value represents log-rank test for TP53 mutation types excluding wild type. c, Hazard ratios for multivariate Cox model fit with 3p deletion and global deletion rate (CIN) across different patient sets (age covariate not shown, error bars indicate 95% CI, p-values represent significance of likelihood ratio test for model fit with and without 3p deletion). d, Venn diagram showing co-occurrence of TP53 mutation and deletions on the 3p chromosome. e, Kaplan-Meyer curves showing survival outcome for all combinations of 3p deletion and TP53 mutation events (colors correspond to patient subsets in panel d).

TP53 and 3p events co-occur and their combination predicts worse clinical outcome

It has previously been shown that genetic alterations often act by redundant or synergistic mechanisms to confer a growth advantage in the tumor16,17. Under the hypothesis that individual events might act in concert, we next examined the 82 prognostic events for pairwise association across the patient cohort. This analysis identified 33 pairs of events that were significantly cooccurring or mutually exclusive (Supplementary Table 3). Among these, a particularly striking finding was that mutation of TP53 and deletion of 3p occur very frequently together, in 179 of 250 HPV– tumors (Table 1, Fig. 1d). While mutation of TP53 has previously been associated with chromosomal instability1, we found that TP53 mutation associates with 3p loss far more frequently than it does with deletions in other chromosomal regions (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables 4-6). Moreover, the combination of TP53 and 3p events led to significantly worse survival than was predicted by either event independently or additively. Thus the synergistic interaction between TP53 and 3p, with respect to both co-occurrence and survival, supports a clear molecular stratification of HNSCC tumors with and without this combination of events (Fig. 1c-e, Methods, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 7).

Table 1.

Co-occurrence and survival interaction of TP53 and 3p events.

| Co-occurrence of TP53 / 3p events | Survival Interaction TP53-3p versus TP53 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | n | Odds Ratio | p | Hazard Ratio** | p ** | |

| TCGA | Discovery | 250 | 6.6 | 10–4* | 5.6 | 0.001 |

| Recent TCGA | Validation | 126 | 10 | 10–6 | ND | ND |

| UPMC | Validation | 48 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 0.01 |

| Pan Cancer | Validation | 4404 | 2.0 | 10–25 | 1.4 | 0.002 |

Bonferroni corrected for test space

Univariate model in patients under 75 years of age only

We found that the TP53-3p combination of events is associated with advanced tumor stage, although the stratification remains prognostic at all stages (Supplementary Figure 6). Furthermore, the prognostic effect cannot be explained by clinical covariates alone and is particularly strong for smokers under 75 years old (175 patients, the majority of the TCGA cohort) for which the hazard ratio was 5.1 for the TP53-3p event relative to patients without this combination (Supplementary Fig. 7, Methods).

To explore whether the interaction between TP53 mutation and 3p deletion could be replicated in new patients, we obtained 126 additional HNSCC HPV– samples that had been deposited in TCGA while our initial study was underway (not included in the January 15, 2014 Firehose run). While these new patients did not yet have sufficient clinical follow-up for survival analysis, we indeed observed the same high co-occurrence of TP53 mutation and 3p deletion (Table 1).

We also analyzed clinical follow-up data for 48 HNSCC HPV– tumors from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center3 for which the exome sequencing and copy number profiles had been previously collected after surgery (UPMC cohort, Supplementary Table 1). We observed that in this cohort, patients whose tumors contain the TP53-3p aggregate event have substantially worse prognosis than patients with TP53 mutation alone, confirming the very large effect seen in the TCGA population (Fig. 2a and Table 1). TP53 and 3p events also co-occurred in the UPMC cohort, although with a lower effect size than in the two TCGA cohorts (Table 1); we suspect this is due to the much higher error rate of DNA sequencing in the earlier UPMC study, resulting in false-negative mutation calls (Methods).

Figure 2. Replication of TP53-3p association.

a, Survival comparison of patients with TP53-3p aggregate event versus those with only TP53 mutation in the independent UPMC cohort. b, Loss of 3p chromosomal arm is associated with lower survival in patients with HPV+ tumors (TCGA and independent cohorts). c, Assessment of 3p loss and TP53 mutation association in TCGA Pan-Cancer cohort (HNSCC excluded). d, Corresponding hazard ratio for multivariate model of three-year truncated survival (shown by dotted line in panel c) when controlling for tissue type, age, and stage covariates. Error bars indicate 95% confidence.

We also sought evidence for the TP53-3p combination in patients with HPV+ tumors, in which TP53 is inactivated via interaction with HPV viral proteins18,19. Analysis of 59 HPV+ tumors from the TCGA and UPMC cohorts showed that TP53 mutation is very rare in the presence of HPV (Odds Ratio 0.01, P = 10−27 by Fisher's Exact Test), consistent with the expectation that the mutation confers little selective advantage once TP53 is inactivated by HPV. Among HPV+ tumors, the 25 tumors with 3p deletion had significantly worse prognosis than the 34 without the 3p event (Hazard Ratio 5.5 ± 2.6, P = 0.004). This finding lends further support for interaction between TP53 and chromosome 3p with respect to survival and stratifies the growing population of patients with HPV+ tumors19 (Fig. 2b).

Another question was whether the TP53-3p interaction is specific to HNSCC or has broader support across diverse tissues. For this purpose, we performed a pan-cancer analysis based on all publicly available molecular data in TCGA (excluding HNSCC patients), covering 4404 patients over an additional 17 cancer types20 (Methods). Although these tissues are molecularly heterogeneous and present with different patient outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 8a-c), we nonetheless found compelling evidence for both the co-occurrence and impact on survival of TP53 mutation and 3p deletion in this broader cohort, even when tissue type, patient age, and staging are accounted for (Fig. 2c-d, Table 1).

Characterization of subtypes defined by combined TP53-3p event

Finally, we investigated whether the major subtypes defined by TP53 and 3p status (Fig. 1e) could be subdivided further by additional molecular markers (Methods). Indeed, we found that the 179 patients with the combined TP53-3p event were well stratified by the additional presence of microRNA mir-548k (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 7c) or mutation of the MUC5B gene (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 7d), both of which were associated with worse prognosis. Mir-548k is near CCND1 and FADD on 11q13.3, which is commonly amplified in HNSCC14. Very recently, this micro-RNA has been shown to have oncogenic behavior in Oesophegeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma cell lines21. While we found that 11q13.3 amplification is associated with survival to a lesser degree than mir-548k expression, the prognostic effect seems to be specific to the expression of the micro-RNA (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 9).

Figure 3. Characterization of molecular subtypes defined by the TP53-3p aggregate event.

Patients with the TP53-3p aggregate event can be further stratified by the presence of a, mir-548k or b, MUC5B. c, Frequency of high gain amplification (top panel) and association with patient survival for gene / miRNA expression (bottom panel) along the 11q13 chromosomal segment. P-values in a and b are Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected for 1008 events a secondary prognostic biomarker screen (Methods). All survival associations are calculated by a likelihood ratio test with age and year of diagnosis used as covariates in the set of 179 patients with the TP53-3p event (TP53-3p negative curves shown for comparison, but not used in computation).

Among patients lacking the TP53-3p event combination, we found strong enrichment for mutations to Caspase 8 as well as Ras and components of Ras signaling (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 1b). These enrichments were replicated in the TCGA molecular validation cohort (Table 2). The mutual exclusivity of Caspase 8 or Ras with TP53-3p provides further support for a TP53-3p defined subtype, and it implicates alternative routes to tumor progression in the absence of the TP53-3p event.

Table 2.

Co-occurrence of TP53-3p aggregate event and gene mutations.

| Co-occurrence of TP53-3p event and CASP8 mutation | Co-occurrence of TP53-3p event and RAS Signaling Pathway† mutation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | n | # patients mutated | Odds Ratio | p | # patients mutated | Odds Ratio | p | |

| TCGA | Discovery | 250 | 21 | 0.13 | 3 × 10–3* | 23 | 0.11 | 3 × 10–4* |

| TP53-3p positive | 179 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| TP53-3p negative | 71 | 15 | 17 | |||||

| Recent TCGA | Validation | 126 | 20 | 0.038 | 7 × 10–8 | 21 | 0.86 | 5 × 10–6 |

| TP53-3p positive | 81 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| TP53-3p negative | 45 | 18 | 17 | |||||

Biocarta SOS1 Mediated RAS Signaling Pathway (Reacome 524)

Bonferroni corrected for test space of 121 gene and pathway mutation events

DISCUSSION

As we approach a full inventory of driver events in cancer22, a key next step is to map and decode the complex network of interactions among individual events. Here, such an analysis was performed to identify a definitive stratification of head and neck cancer based on the largest tissue bank and dataset in existence. We have shown that TP53 mutation, a well-studied driver event which leads to poor patient survival, is nearly always accompanied by specific loss of chromosome 3p (Fig. 1d, Table 1). As has been argued for other cancer mutations17,23, the frequent co-occurrence of TP53 and 3p alteration implies a selective advantage of cells acquiring both genomic events. In this study, the detection of the TP53-3p interaction was possible due to the high prevalence of each event individually, and their high (marginal) associations with patient survival.

While our study focused almost entirely on a single compelling interaction, our full analysis uncovered an additional 32 interactions in HNSCC which remain to be investigated (Supplementary Table 3). It is likely that this number is an underestimate, as low frequency and/or non-prognostic events were not evaluated. As cancer cohorts become larger, analyses such as this will become more powered, creating the opportunity to re-evaluate the cancer landscape from the perspective of pairwise and ultimately higher-order interactions among events.

Our analysis identifies two distinct clinical and molecular paths to cancer in HPV– HNSCC patients. The first group, characterized by TP53 mutation and loss of the 3p chromosome, is associated with advanced clinical stage and common risk factors such as smoking. Nonetheless, this group tends to have very poor outcomes even when evaluated independently of these risk factors (Supplementary Fig. 7). The second group of patients, lacking the TP53-3p combination of events, is characterized by mutations to RAS signaling and Caspase 8 (Table 2) and, ultimately, less aggressive tumors.

Further study is clearly warranted to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of these two groups of patients, with the goal of using such molecular stratification alongside clinical variables to inform patient treatment. Open questions relate to mechanism and the ordering of TP53 and 3p events. What is the factor or factors encoded on chromosome 3p that are responsible for the interaction with TP53? Does one event necessarily precede the other and is a particular order required for poor survival? It is plausible that genomic instability primed by TP53 mutation gives rise to loss of activity of a key factor encoded on chromosome 3p, but other scenarios are possible. Regardless, since the interaction of 3p with TP53 or HPV status is independent of tumor stage, treatment of HNSCC patients might be modified to coincide with this specific molecular classification. In HPV– HNSCC, the need for patient-tailored treatment programs is especially great, as we are currently in an era where we have maximized toxicity of existing regimens without necessarily improving outcome in cancers.

Our results also underscore the importance and value of public efforts such as TCGA in gathering, organizing, and distributing genomic data. Our work builds on the exemplary TCGA data collection and analysis pipeline20 to integrate data across different measurement platforms, with the goal of finding higher-order interactions of molecular events. Following the example of TCGA, we have documented and made public all analyses conducted in this study, ranging from data download to processing, exploratory analyses, statistical modeling, and visualization (Methods). With such a large and complex dataset, transparency and reproducibility of analysis is essential to provide a clear understanding of the methodology and to allow for further mining of results and extension to new datasets.

ONLINE METHODS

1. Availability

All data-retrieval and processing steps are documented in a series of IPython notebooks9 available along with source code online at (https://github.com/theandygross/TCGA). These notebooks provide fully executable instructions for reproduction of the analyses and generation of figures and statistics for this study.

2. Molecular Data

Data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas Genome Data Analysis Center (GDAC) Firehose website (https://confluence.broadinstitute.org/display/GDAC/) using the firehose_get data-retrieval utility. All data were downloaded from the January 15th, 2014 standard data and analyses run unless otherwise specified. In order to maintain coherency of the analysis across different data layers and cancer types, we used Level 3 normalized molecular data as the input to our analysis. The use of the GDAC pipeline is intended to make these results easy to update as more TCGA data become available.

For a number of pan-cancer samples we generated mutation calls from TCGA aligned BAM files obtained from the UCSC Cancer Genomics Hub (https://cghub.ucsc.edu/). These calls were only used for patients with sequenced exome data that have yet go through the Firehose processing pipeline. Somatic mutation calls were made by running the MuTect mutation calling program24 and the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) SomaticIndelDetector25 function on targeted regions with default parameters. All steps for downloading and processing this data are documented in the analysis notebooks and accompanying software repository. All mutation calls generated for this analysis are included as Supplementary Table 8. While these calls have yet to go through manual curation, we benchmarked this pipeline against TCGA working group mutation calls and found very high overlap with 94% sensitivity and 96% specificity.

3. Pathway Data

Pathway data were downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database26 (mSigDB). Version 3 of the canonical pathway gene-sets was used for this analysis.

4. Candidate biomarker construction

Mutation calls were extracted from the annotated MAF files obtained from the Firehose and filtered to include only non-silent mutations. Each patient was associated with a binary vector in which each position represents a gene; the position is set to 1 if the gene is observed to harbor one or more mutations in the patient and set to 0 otherwise. Mutation meta-markers were constructed by collapsing genes within a pathway gene-set via a logical OR such that the pathway is considered altered in a patient if any of its genes have a mutation (Supplementary Fig. 1b-c). Pathway markers that were characterized by a single highly mutated gene or were highly correlated with mutation rate (Mann-Whitney U test, P < .01) were filtered.

Copy-number aberrations were extracted from the GISTIC227 processing pipeline included in the standard Firehose analysis run. For biomarker construction data aggregated on significantly altered lesions (as deemed significant at the default 99% confidence settings) were used.

mRNA and miRNA expression data were obtained from the Level 3 normalized gene-by-patient matrices generated as part of the Firehose analysis pipeline. Data were log2 transformed. Genes/ miRNAs were first filtered based on differential expression comparing the full set of tumor expression profiles with the 34 profiles available for matched normal tissue (t-test, cutoff at P < .01). A pattern of background expression was estimated by taking the first principal component of non-differentially expressed genes or miRNAs. This background signal is meant to approximate the most common non-tumor related variation in expression due to inherent properties of the cohort such as population substructure or tissue specific expression changes. Real valued features with high correlation (Pearson Correlation, P < 10−5) to this background expression pattern were filtered. For the survival analysis, only the top 300 (of a possible 20502) differentially expressed genes were included in the analysis to limit the burden of multiple hypothesis correction (all 251 differentially expressed miRNA were used).

Markers used in this analysis consisted of binary markers and continuous valued markers. Binary markers were used when expression was only present (having more than ½ read per million) in a moderate fraction of the cohort (between 20 patients and half of the cohort). Real valued gene and miRNA expression levels were used for differentially expressed features not assigned as binary markers. Gene expression meta-markers were constructed from the loading of the first principal component of the reduced gene-by-patient matrix defined by each gene set. Due to similarity of gene-sets causing redundant gene expression meta-markers, marker pairs with high correlation (Spearman rho > .7) were reduced to a single informative marker by choosing the marker with the greatest differential expression. For the survival analysis, continuous valued markers were transformed into binary events prior to testing by setting a threshold that minimized the difference in variance between the resulting two groups. This was used to capture the skew of the distribution and assign the patients on the tail of the expression distribution as having an expression event (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

5. Clinical Data

Clinical data were downloaded directly from the TCGA Data Portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). All outcomes reported relate to all-cause survival. Survival times were censored after five years to reduce the confounding effect of patient age. For Fig. 2d, survival times were censored after three years to show the specific effect within this time window, but all other figures and all statistics cited in the paper use five-year survival. While data on comorbidity is limited for this cohort, from other studies we can estimate the competing mortality within this time-frame to be about 20%28,29. We expect the actual effect of such confounding to be minimal as separation in the survival curves that we observe generally occurs within the first two years, during which time we expect non-cancer associated death rates to be much lower.

For the primary and secondary survival screens, clinical data with missing data were used but statistics were only calculated on patients with data reported. In multivariate analysis (Supplementary Figure 7) missing value indicators were used.

6. HPV Status

HPV calls from sequencing data were obtained from the TCGA HNSCC analysis working group. Due to the incompleteness of this dataset, this information was supplemented with HPV status called from a PCR-based MassArray Assay diagnostic provided on the TCGA data portal for patients where sequence-based data were not available.

7. Prioritization of Prognostic Events

Feature selection is preformed prior to prognostic event prioritization. Events are selected for which at least 5% of patients are assigned to each group.

Prognostic events (Fig. 1a) are prioritized via a likelihood ratio test comparing a Cox-proportional hazards model30 fit with a candidate biomarker and covariates against a null model fit with the covariates alone. Age and the binary variable patient age > 75 are used as covariates (both age variables are used to model a non-linear association of patient age with survival). A multiple-hypothesis testing correction is employed which uses the method of Benjamini and Hochberg31 to control for the false discovery rate across the entire pooled space of tested features. After multivariate testing, a univariate log-rank test is assessed for each event and features with high multivariate significance, but low univariate significance (P < 0.05) are filtered from the pool of prognostic events.

As discussed in the text and in Figure 3, we conducted a second prognostic screen within the 179 patients with the TP53-3p aggregate event. For this analysis feature construction was repeated, resulting in 1008 candidate biomarkers (note that this number was higher than the primary screen due to more events passing the 5% threshold). During this secondary screen, we found the patient year of diagnosis to have a large impact on outcomes. For this reason we included this variable as a covariate in this screen.

8. Statistical Analysis of TP53-3p Interaction on Survival

To asses the role of an interaction term in a statistical model of patient outcomes we performed leave-one-out cross-validation on a logistic regression model as shown in Supplementary Figure 5. To convert the survival data into a binary classification problem, we organized patients into two classes depending on whether they were surviving or deceased at T years after surgery. In this analysis, the ratio of deceased to surviving patients is artificially high due to the ability to observe a death in a shorter followup than the full time interval required to annotate a patient as surviving (i.e. the basis of the Cox censorship problem). To reduce this bias, we removed patients with an observed death but a time of surgery after a set year (2013 – (T – 1)). As the problem was often unbalanced (the number of surviving patients differed from the number of deceased), re-weighting was preformed to give both classes equal weight. A multivariate Cox model fit to the most significant model is also shown in Supplementary Table 7.

9. University of Pittsburg Medical Center Cohort

3p chromosomal status was estimated via the median copy number of the twelve genes on the 3p14.2 locus. Matched exome and copy-number data were available for 48 / 63 patients with HPV– tumors. In preliminary analysis we found the UPMC cohort to have a significantly lower overall mutation rate than the TCGA cohort, with a median of 73 mutations per patient as compared to 104 mutations per patient in TCGA (Mann-Whitney U test, P < .001). This can likely be attributed lower depth of coverage and/or less sophisticated variant calling techniques as the UPMC study was one of the first large whole exome molecular cohorts and predates the TCGA data collection by about two years.

10. Pan-cancer Analysis

Pan-cancer data were downloaded and processed in the same manner as the HNSCC cohort. 3p chromosomal status was estimated via the median copy number of the twelve genes on the 3p14.2 locus.

In order to limit the heterogeneity of the pan-cancer cohort such that differences in molecular characteristics could be assessed, we performed a number of pre-processing steps. This reduced the patient cohort from 7081 to 4404 patients appropriate for survival analysis through the following filters:

Only primary tumors were used for all patients, metastatic tumors were discarded. Glioblastoma patients were excluded due to the extremely low survival rate (6% five year survival).

Diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, kidney chromophobe, thyroid carcinoma, and prostate adenocarcinoma patients were removed due to extremely high rates of survival in the cohorts (84%, 86%, 90%, and 96% five year survival).

Adrenocortical carcinoma, esophageal carcinoma, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma were excluded due to low sample counts (14, 39, and 69 patients in each tissue, respectively). Patients older than 85 years of age were excluded from the analysis to limit confounding from age (115 patients, Hazard ratio = 2.2 ± 3).

Patients with high levels of residual tumor were excluded (66 patients, Hazard ratio = 2.9 ± .5).

Stage IV patients were excluded (612 patients, Hazard ratio = 2.0 +/- .1)

To limit circularity, HNSCC patients were excluded from all pan-cancer calculations but remain Supplementary Fig. 8 to allow for comparison to other tissue types.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Messer and A. Tward for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge support for this study from the National Institutes of Health (P50 GM085764, P41 GM103504 to TI; T32 DC000028 to RO, Burroughs Welcome Fund CAMS to QN; P50 CA097190 and The American Cancer Society to JG; K07CA137140 to AME. J.P.S. is supported in part by grants from the Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research and a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Young Investigator Award.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS

A.M.G., R.K.O., and T.I. conceived the study. A.M.G carried out most analyses. R.K.O., J.P.S., M.C., C.S.C, E.E.C., S.M.L, Q.T.N., and D.N.H. provided expertise. M.H. and H.C. aided in bioinformatic analysis. A.M.E. and J.G. collected and compiled clinical follow-up data for UPMC cohort. A.M.G. and T.I. wrote the manuscript with assistance from other authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

URLS

Study source code and analysis notebook repository, https://github.com/theandygross/TCGA Broad Firehose, https://confluence.broadinstitute.org/display/GDAC/Home TCGA Data Portal, https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga UCSC Cancer Genomics Hub, https://cghub.ucsc.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJM, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mroz EA, et al. High intratumor genetic heterogeneity is related to worse outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Genetic Heterogeneity and HNSCC Outcome. Cancer. 2013;119:3034–3042. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stransky N, et al. The Mutational Landscape of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung CH, et al. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using patterns of gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter V, et al. Molecular Subtypes in Head and Neck Cancer Exhibit Distinct Patterns of Chromosomal Gain and Loss of Canonical Cancer Genes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickering CR, et al. Integrative Genomic Characterization of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Identifies Frequent Somatic Drivers. Cancer Discovery. 2013;3:770–781. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temam S, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Copy Number Alterations Correlate With Poor Clinical Outcome in Patients With Head and Neck Squamous Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2164–2170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lui VWY, et al. Frequent Mutation of the PI3K Pathway in Head and Neck Cancer Defines Predictive Biomarkers. Cancer Discovery. 2013;3:761–769. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez F, Granger BE. IPython: A System for Interactive Scientific Computing. Computing in Science & Engineering. 2007;9:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poeta ML, et al. TP53 Mutations and Survival in Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:2552–2561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohta M, et al. The FHIT gene, spanning the chromosome 3p14.2 fragile site and renal carcinoma-associated t(3;8) breakpoint, is abnormal in digestive tract cancers. Cell. 1996;84:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosin MP, et al. Use of allelic loss to predict malignant risk for low-grade oral epithelial dysplasia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Partridge M, Emilion G, Langdon JD. LOH at 3p correlates with a poor survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 1996;73:366–371. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meredith SD, et al. Chromosome 11q13 amplification in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Association with poor prognosis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:790–794. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890070076016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Partridge M, et al. The prognostic significance of allelic imbalance at key chromosomal loci in oral cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1999;79:1821–1827. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6990290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Research. 2011;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bredel M, et al. A network model of a cooperative genetic landscape in brain tumors. JAMA. 2009;302:261–275. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas M, Pim D, Banks L. The role of the E6-p53 interaction in the molecular pathogenesis of HPV. Oncogene. 1999;18:7690–7700. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marur S, D'Souza G, Westra WH, Forastiere AA. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11:781–789. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang K, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nature Genetics. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Y, et al. Identification of genomic alterations in oesophageal squamous cell cancer. Nature. 2014;509:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature13176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence MS, et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014;505:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xing F, et al. Concurrent loss of the PTEN and RB1 tumor suppressors attenuates RAF dependence in melanomas harboring (V600E)BRAF. Oncogene. 2012;31:446–457. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cibulskis K, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nature Biotechnology. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberzon A, et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1739–1740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mermel CH, et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biology. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mell LK, et al. Predictors of competing mortality in advanced head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:15–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farshadpour F, et al. Survival analysis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: influence of smoking and drinking. Head Neck. 2011;33:817–823. doi: 10.1002/hed.21549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox DR. Analysis of survival data. (Chapman and Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.