Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a global health problem affecting 3% of the world's population (about 180 million) and a cause of both hepatic and extrahepatic diseases. B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, whose prototype is mixed cryoglobulinemia, represent the most closely related as well as the most investigated HCV-related extrahepatic disorder. The association between extrahepatic (lymphoma) as well as hepatic malignancies (hepatocellular carcinoma) has justified the inclusion of HCV among human cancer viruses. HCV-associated manifestations also include porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus, nephropathies, thyreopathies, sicca syndrome, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, diabetes, chronic polyarthritis, sexual dysfunctions, cardiopathy/atherosclerosis, and psychopathological disorders. A pathogenetic link between HCV virus and some lymphoproliferative disorders was confirmed by their responsiveness to antiviral therapy, which is now considered the first choice treatment. The aim of the present paper is to provide an overview of extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection with particular attention to B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Available pathogenetic hypotheses and suggestions about the most appropriate, currently available, therapeutic approaches will also be discussed.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Extrahepatic manifestations, Lymphoproliferative disorders, Mixed cryoglobulinemia, Lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is associated with several extra-hepatic disorders (extrahepatic manifestations of HCV = EHMs-HCV)[1,2]. These latter may be classified into four main categories including: (1) EHMs-HCV that are characterized by a very strong association as demonstrated by both epidemiological and pathogenetic evidence; (2) disorders for which a significant association with HCV infection is supported by substantial data; (3) associations that still require confirmation and/or a more detailed characterization compared to similar pathologies of different etiology or idiopathic nature; and (4) anecdotal observations (Table 1)[3]. B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) represent the most closely related as well as the most investigated forms and should be considered an ideal model for both clinico-therapeutic and pathogenetic deductions.

Table 1.

Classification of extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection

| A: Association defined on the basis of high prevalence and pathogenesis |

| Mixed cryoglobulinemia (complete or incomplete clinical syndrome) |

| B: Association defined on the basis of higher prevalences than in controls |

| B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Monoclonal gammopathies |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda |

| Lichen planus |

| C: Associations to be confirmed/characterized |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis |

| Thyroid cancer |

| Sicca syndrome |

| Alveolitis-Lung fibrosis |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Non-cryoglobulinemic nephropathies |

| Aortic atherosclerosis |

| D: Anecdotal observations |

| Psoriasis |

| Peripheral/central neuropathies |

| Chronic polyarthritis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Polyartheritis nodosa |

| Bechet’s syndrome |

| Poly/dermatomyositis |

| Fibromyalgia |

| Chronic urticaria |

| Chronic pruritus |

| Kaposi’s pseudo-sarcoma |

| Vitiligo |

| Cardiomyopathies |

| Mooren corneal ulcer |

| Erectile dysfunctions |

| Necrolytic acral erythema |

HCV-RELATED LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS

Mixed Cryoglobulinemia

Mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC) is the most documented HCV-related extrahepatic disorder[4-6]. The strong association between HCV and MC has been confirmed by serological and molecular investigations[4,6,7]. This disorder is defined by the presence of serum immunoglobulins (Igs) that become insoluble below 37°C and can dissolve by warming serum (cryoglobulins, CGs). According to Brouet et al[8], CGs are classified on the basis of their Ig composition: in type I cryoglobulinemia CGs are composed of a pure monoclonal component, usually sustained by an indolent B-cell lymphoma, whereas type II and type III MC are characterized by a mixture of polyclonal IgG and monoclonal IgM or by polyclonal IgG and IgM, respectively. In MC, IgG and IgM with rheumatoid factor (RF) activity participate in the com-position of circulating immunocomplexes (CIC). The IgM monoclonal component in type II MC is represented by RF molecules that most frequently display the WA cross-reactive idiotype[9]. Type II (MC II) accounts for 50%-60% of MC, and type III;(MC III) for the remaining 30%-40%. Cryoproteins are HCV RNA enriched in comparison with supernatants in HCV-infected patients. Studies performed in unselected populations of chronic HCV-positive subjects showed a high prevalence of serum CGs, ranging from 19% to > 50% according to different studies[10,11]. However, CGs are generally present at low levels and symptoms are generally absent or very mild, whereas clinically evident MC - MC syndrome or MCS would be evident in 10%-15% to 30% of MC subjects and in 5%-10% of all HCV infected patients[10-12].

The most common symptoms of MCS are weakness, arthralgias, and purpura (Meltzer and Franklin triad). Raynaud's phenomenon, peripheral neuropathy, sicca syndrome, renal involvement, lung disorders, fever, and hematocytopenia may also be observed[13]. In a recent study involving 231 Italian MC patients, peripheral neuropathy was observed in the majority of cases, representing the most frequent clinical feature after the triad, followed by sicca syndrome, Raynaud's phenomenon and renal involvement[14].

In MC patients, peripheral neuropathy includes mixed neuropathies, which are prevalently sensitive, axonal, and can manifest themselves as symmetrical distal neuro-pathies, multiple mononeuritis or mononeuropathies[15-17]. Involvement of the central nervous system is unusual and generally presents as transient dysarthria and hemiplegia. Pathological findings show axonal damage with epineural vasculitic infiltrates and endoneural microangiopathy.

The association between MC and glomerulonephritis has been clearly demonstrated[18,19]. Nephropathy is observed in 20% of patients at MCS diagnosis, and in 35%-60% during follow-up[14,19]. The presence of renal involvement is one of the worst prognostic indices in the natural history of MCS[14]. MC-related nephropathy is clinically characterized by hematuria, proteinuria (sometimes in nephritic range, i.e. > 3 g/24 h), edemas, and renal failure of variable grade. The histological picture is similar to that of idiopathic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, but characterized by capillary thrombi consisting of precipitated cryoglobulins under light microscopy and widespread deposits of IgM in capillary loops. Histological analysis shows a thickening of glomerular basal membrane, cellular proliferation and infiltration of circulating macrophages. From a clinical point of view, MC patients frequently present with one or more subclinical signs of renal involvement, including asymptomatic hematuria, without nephrotic proteinuria (< 3 g/24 h), with normal or only fairly reduced renal function (creatinine < 1.5 mg). In 30% of cases, the clinical manifestation of MC may be acute nephrotic syndrome[4]. Hypertension may be seen in 80% of MC patients with renal involvement[20].

Renal manifestations represent a negative prognostic factor in MC, even if their course may vary. However, in the long term, MC-related nephropathy may progress to terminal chronic renal failure requiring dialysis in up to 15% of patients[21].

The association between MC and severe liver damage has been widely discussed[1,2,9,22,23]. Recent studies have shown an epidemiological association between MC and severe liver damage[10,24] as well as between MC and liver steatosis[25]. In the previously cited study performed on 231 MC patients, survival analysis according to the Kaplan-Meier method revealed a significantly lower cumulative 10-year survival, calculated from time of diagnosis, in MC patients when compared with expected death in the age- and sex-matched general population. Moreover, significantly lower survival rates were observed in males and in subjects with renal involvement, the most frequent causes of death being nephropathy (33%), malignancies (23%), liver involvement (13%), and diffuse vasculitis (13%)[14].

No standardized criteria are presently available for diagnosis of MC syndrome. However, valuable classifications have been proposed[26]. In the presence of clear clinical and serological data (i.e., purpura, MC, reduced C4 values, organ involvement), the diagnosis of MCS is relatively easy. However, the diagnosis is frequently only suggested by one or more altered laboratory data (RF-test + and/or mixed cryoglobulinemia and/or reduced C4 values) with or without mild symptoms (arthralgias and/or asthenia). Moreover, some HCV-positive subjects may show clinically evident MCS, though incomplete from a serological point of view, mainly with the temporary absence of circulating CGs. This paradox may be explained by the fact that the rate of CGs responsible for vasculitic damage in MCS varies over time among different subjects as well as within the same patient, ranging from 0% to 100%[3]. In addition, the difficulty in correctly determining the presence of CGs, due to their thermolability, should be taken into account.

Determination of serum CGs and serum sample collection must be in accordance with laboratory standards as follows: withdrawal of 20 mL of whole blood at warm temperature; centrifugation for 2-3 min at 37°C; rapid collection of serum (supernatant); incubation of serum at 4°C for one week; evaluation of CGs present at d 7; isolation and washing of CGs by phosphate buffered saline at 4°C; characterization of Ig and IgM monoclonality in the cryoprecipitate. Due to the fact that some mixed CGs are present in low concentrations, differentiation between type II and III CGs often requires a more sensitive method of immunochemical characterization such as electroimmunofixation or western blot, than conventional immunoelectrophoresis[27].

Several data, including the presence of a clonal expansion of B-lymphocytes (BL) in peripheral blood and/or liver infiltrates[28-31], and the histopathological features of the bone-marrow and liver lymphoid infiltrates (see below) confirm the lymphoproliferative nature of MC. Several studies show that a B-cell clonal expansion (in particular of RF B-cells) underlies MC, that this condition is associated with Bcl-2/JH rearrangement (see below), and that MC-II can evolve into a frank B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) in approximately 8%-10% of cases after a long period of time[14].

From a histopathological point of view, the deter-mination of monoclonal lymphoproliferation of uncertain significance (MLDUS) in subjects with clinico-laboratory features of MC-II is typical[3,32-34]. MLDUS represents oligoclonal proliferations of small BL, preferentially located in the bone marrow and liver. In these organs, MLDUS is generally present with phenotypical and histological aspects comparable to indolent B-cell lymphoma. A deeper, immunomorphological analysis reveals two different varieties: a first and more frequent variety, with analogous features to B-cell chronic lymphatic leukemia (CLL)/small cell lymphoma and a second, less frequent, lymphoplasmacytic-like form. The incidence of these histological forms varies in different reports[33,35-40].

LYMPHOMA

HCV-associated lymphatic malignancies may be observed during the course of MC or they may be idiopathic forms. About 8%-10% of MC-II evolve into lymphoma[36,41], generally after long-lasting infection, as demonstrated also by the advanced age of patients who develop HCV-related lymphoma. In a recent survey, MC patients had a 35 times higher risk of NHL than the general population[42].

A significant association between B-cell derived NHL and HCV infection was initially reported in Italian subjects[43-49], and subsequently confirmed by a large majority of international studies[33,42,47,50-54]. However, discordant data appeared in northern European and North American surveys[55-60], and it is now evident that a clear south/north gradient of prevalence exists, in part reflecting different HCV infection prevalence in the general population, and suggesting the contribution of environmental and/or genetic factors[54].

From a histopathological point of view, although all histological types can virtually be found, B-cell derived NHL is the most common of the HCV-related lymphatic malignancies[33,45,47,48,61-64].

Reports in the literature indicate varied incidences of different histotypes that may in part be related to different diagnostic-classification approaches[40,64-66]. However, the most diffuse varieties appear to be peripheral B-cell-derived indolent NHL. According to the REAL/WHO classification[67,68], the most prevalent forms include follicular lymphoma, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocyte lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, and marginal zone lymphoma[33]. Among the marginal zone lymphomas, a special association with HCV infection was reported for the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma[64,69,70], as well as the splenic forms, as confirmed by some reports indicating that marginal splenic lymphoma regressed after antiviral therapy, in spite of previous ineffective chemotherapy[71-72].

Finally, it is of note that a serum monoclonal gammo-pathy, most frequently type IgM/K, was included among HCV-associated LPDs[73]. In most HCV-positive patients, MG was classified as MGUS (monoclonal gammopathies of uncertain significance), which has to be monitored in order to exclude the possibility (though remote) of evolution into multiple myeloma. Currently, a few HCV-positive patients with monoclonal gammopathy are considered affected by myeloma according to clinico-pathological characteristics[68,74,75].

PATHOGENESIS OF HCV-RELATED LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS

The pathogenesis of HCV-related lymphoproliferative disorders is at present unknown, although knowledge has accumulated during the last decade which suggests interesting pathogenetic hypotheses.

First, the individuation of HCV lymphotropism at the beginning of the 1900s led to the hypothesis of a causal link between infection of lymphatic cells and autoimmune-lymphoproliferative disorders[76]. In an initial study, it was observed that both HCV positive strand (genomic) and negative strand (antigenomic = replicative intermediates) could be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) taken from patients with chronic HCV infection; that both B and T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages may score positive and that the mitogen stimulation of PBMC cultures increased the determination of HCV sequences, with particular reference to negative strand ones. In addition, the notion of better detection of HCV lymphatic infection in HIV coinfected patients was introduced[77]. A lot of information about HCV lymphotropism, in both in vivo and in vitro systems, has accumulated during the past decade. These studies were able to better characterize this viral prerogative by the use of more specific methods or study models[78-84]. However, it was impossible to obtain a clear scientific confirmation of a direct link between HCV lymphotropism and LPD pathogenesis, mostly due to difficulties in the identification of valuable scientific models, in spite of the demonstration of a stronger involvement of the lymphatic system in HCV infection in patients with MC than in HCV patients without[5,85], and, more recently, the favoring effect of B-cell infection in promoting lymphatic cell proliferation[86]. By contrast, several interesting data suggest a role only indirectly played by HCV infection in LPD pathogenesis through the host's immune response[30,87-90]. Several studies focused on the importance played by sustained antigenic stimulation, partly analogous to mechanisms which may play a key role in lymphomagenesis due to H pylori. In this light, the identification of the specific binding between the HCV E2 protein and the CD81 molecule - which is ubiquitous but particularly abundant on the B-cell surface[91] - led to the hypothesis of a possible role played by HCV in the promotion of a consistent polyclonal B-cell response to viral antigens which favor the development of LPDs. According to this working hypothesis, the viral infection will favor lymphomagenesis in a linear, progressive way until the possible malignant transformation.

Contrasting data, showing that HCV may favor muta-tions of immunoglobulin genes and oncogenes by a "hit and run" mechanism, have recently been obtained both in cell lines and in cultured cells taken from HCV-infected patients[92]. This study was justified by previous observations showing the significant association existing between Bcl-2 rearrangement (14;18 translocation) and chronic HCV infection, especially in those patients developing type II MC[93-98], and MALT lymphoma[99]. In type II MC patients, the analysis of synchronous and metachronous blood samples showed the clonal expansion of B-cells harboring this chromosomal rearrangement[95]. In addition, it was possible to demonstrate the overexpression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein with a higher Bcl-2/bax ratio in t(14;18)-positive B-cell samples[95], as well as a modification of detectability of t(14;18) B-cell clones following antiviral treatment[100]. Only virologically effective treatments led to the regression of clones, with consequent lack of t(14;18) - positive cells in peripheral blood at the end of treatment, whereas this effect was not observed in non-responder patients[100]. Regression of B-cell lymphoproliferation after effective antiviral treatments was also observed in different studies which utilized different parameters[101] and was interpreted as a consequence of the dependence of such lymphoproliferation on viral antigenic stimulation.

More recently, the availability of the study model of MC patients experiencing a sustained virological response to antiviral treatments and undergoing long term post-treatment follow-up, has provided new data and, in turn, opened the way for a series of previously unexpected issues. This analysis, that was performed by the use of very sensitive methods for HCV sequence determination, allowed the identification of subjects which, even if scoring persistently HCV RNA-negative in both serum and liver samples, were HCV RNA positive in lymphatic cells and showed persistence of MCS stigmata ([102] and Zignego et al, submitted paper). In contrast, this behavior was not observed in patients who showed complete viral clearance, and in whom MCS persistently disappeared. These obser-vations, after more than a decade, strongly suggested the possibility of a role played by HCV lymphotropism, as initially supposed, even if the exact mechanisms involved are at present unknown.

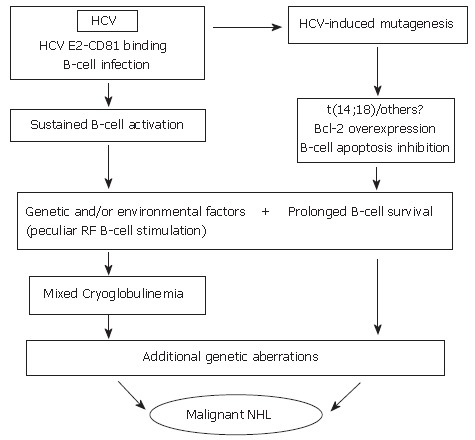

Overall, on the basis of such data, it is possible to suggest that HCV infection may lead to the pathogenesis of LPDs through a complex, multistep pathogenetic mechanism including - as the initial, favoring event-a strong and persistent stimulation of the B-cell compartment by viral epitopes. This would be responsible for sustained polyclonal expansion - physiological, even if abnormal in quantitative terms - which in turn would favor mistakes in immunoglobulin gene rearrangement (VDJ rearrangement) processes such as t(14;18) translocation, thus favoring the abnormal survival of corresponding B-cells. Apart from these mechanisms, only indirectly related to HCV, the role played by the active infection of B cells and the possible intervention of a direct mutagenic effect of HCV by a "hit and run" mechanism following their infection should be taken into account and be the object of future study. In the presence of a background of predisposing constitutional-genetic factors, i.e., a low stimulation threshold of RF-B cells, the existence of factors leading to inhibition of B-cell apoptosis would favor the transition from polyclonal activation and expansion of RF B cells producing poly-clonal IgM RF molecules (type III MC), to the emergence of a dominant clone producing a monoclonal IgM RF (type II MC). In other words, the switch from a polyclonal MC secondary to the infection - an epiphenomenal effect - to the oligo-monoclonal one, might evolve into a lymphatic malignancy. In this light, some data exist suggesting that infected B-cells obtained from MC patients may correspond to MC-typical RF B-cells[103], and that t(14;18) positive B cells may correspond to RF B-cells (Giannini et al, unpublished results). On the other hand, it is well known that abnormal B-cell survival would per se favor the accumulation of genetic mutations, possibly leading to the final neoplastic transformation (Figure 1). Analogous to the association between several different autoimmune and or lymphoproliferative disorders and a known pathogenetic mechanism, it is very plausible that, in some cases, an HCV-associated LPD showing similar clinical features may arise from alternative pathogenetic sources not involving Bcl-2 overexpression and/or, more specifically, Bcl-2 rearrangement[103].

Figure 1.

Hypothetical interpretation of the complex relationship between chronic HCV infection, and lymphoproliferative disorders. During chronic infection, HCV is responsible for sustained B-cell proliferation. Factors favoring polyclonal B lymphoproliferation may include the specific binding of HCV E2 protein to CD 81 (a tetraspannin which, on the B-cell surface, is part of an activating molecular complex lowering the threshold of B-cell activation by specific epitopes)[92,95], as well as the specific activation of reactive T-cells by HCV and cytokines. Favoring factors may also be represented by the persistent infection of B-cells[78,95]. Resulting sustained B-cell proliferation would in turn favor the occurrence of t(14;18) translocation and/or other errors during V(D)J rearrangement processes in germinal centers located in secondary lymphoid organs which, in case of HCV infection, would also include the liver[28]. A more direct role played by HCV lymphatic infection via viral mutagenic properties cannot be excluded[93]. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic protein overexpression in B-cells would result and lead to abnormally prolonged B-cell life. In predisposed subjects, in presence of unknown environmental, viral and/or genetic factors, HCV infection could lead to sustained production of cryoglobulins. These predisposing factors may include the peculiar susceptibility of IgM RF producing B-cells (RF B-cells) to be activated and/or the presence of particular viral variants bearing epitopes capable of selectively activating RF B-cells. It is tempting to hypothesize that the Bcl-2 rearrangement, by inhibiting B-cell apoptosis, may favor the lack of silencing higher affinity, potentially pathological RF B-cells[142], possibly leading to the development of MC syndrome. In turn, abnormal survival of B-cells would favor the acquisition of additional genetic aberrations which might ultimately lead to transformation to a frank B-cell malignancy[33].

THERAPY OF HCV-RELATED LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS

Mixed cryoglobulinemia

Most information about treatment of HCV-related LPDs is derived from studies concerning MCS. This syndrome, before the identification of its viral etiology, was interpreted and treated as an "essential" autoimmune/lymphoproliferative disease by using a combination of anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive drugs, as well as procedures able to reduce the amount of circulating immunocomplexes (cryoglobulins) such as plasma exchange and low antigen content diet (LAC diet). The identification of the viral etiology led to the attempt to eradicate HCV with interferon (IFN)-based treatments. Interestingly, because of its antiproliferative properties, IFN was successfully used in the treatment of MCS even before the identification of HCV[104,105]. Several studies, utilizing different therapeutic protocols, have been carried out (Table 2), and the usefulness of IFN therapy for HCV-related MC is now firmly established. However, an accurate meta-analysis of performed studies is still hampered by the heterogeneity of regimens used so that an optimum regimen has not yet been determined nor have prognostic criteria been accurately delineated.

Table 2.

IFN monotherapy in HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemia

| Author | Year | No. patients | Treatment | CS | Treatment duration (months) | EOT response | Sustained response |

| Ferri | 1993 | 15 | 2 MIU IFN/d (1 m) – 2 MIU IFN × 3/w (5 m) | Yes | 6 | 80% | |

| Ferri | 1993 | 26 | 2 MIU IFN/d (1 m) – 2 MIU IFN × 3/w (5 m) | Yes | 6 | 100% | 0 |

| Marcellin | 1993 | 2 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | 6 | 50% | ||

| Johnson | 1993 | 4 | 1-10 MIU IFN | No | 2-12 | 75%1 | |

| Misiani | 1994 | 27 | 1.5 MIU IFN × 3/w (1 w) – 3 MIU IFN × 3/w (23 w) | No | 6 | 60% | 0 |

| Dammacco | 1994 | 15 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 12 | 53.30% | 25% |

| 16 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | Yes | 12 | 52.90% | 33.30% | ||

| Johnson | 1994 | 14 | Variable IFN | No | 01 | ||

| Mazzaro | 1994 | 18 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 28% | ||

| Mazzaro | 1995 | 18 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 6 | 28% | 11% |

| 18 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 12 | 39% | 22% | ||

| Casaril | 1996 | 25 | 6 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 6 | 52%2 | |

| Cohen | 1996 | 20 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | 60%3 | 9%3 | ||

| Akriviadis | 1997 | 20 | 3-5 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 6-12 | 65%2 | 33%2 |

| Casato | 1997 | 31 | 3 MIU IFN/d (3 m) – 3 MIU IFN × 3/w (≥ 9 m) | No | ≥ 12 | 62% |

CS: corticosteroids; MIU: millions of international units; d: daily; m: months; w: week; EOT: end of treatment; s: Kidney function improvement;

: Cryoglobulins disappearance,

: both complete and partial MC syndrome response. From: Zignego A.L. Postgraduate Course of the 41st Annual Meeting of the EASL, 2006, modified.

Antiviral treatment essentially followed the evolution of treatment of HCV-related chronic liver disease, with some latency. In a first series of studies, the effects of IFN monotherapy were tested[22,106-116] (Table 2). When compared with HCV-related chronic hepatitis, treatment of MC was associated with a relatively poorer response and high relapse rate. The frequent relapse of both HCV replication and MC syndrome at the end of IFN treatment suggested the combination with ribavirin (RBV) (Table 3): this therapeutic option appeared valid in several studies[117-120]. Interestingly, it has been shown that RBV monotherapy also decreases transaminase levels and MC-related symptoms, probably due to its immunomodulatory effects[121-123]. Further improvement in the sustained virological response (SVR) rate was obtained by the introduction of pegylated IFNs[124-126] (Table 3). However, additional controlled studies are needed to gain definitive information.

Table 3.

Combined IFN (recombinant or pegylated) + ribavirin therapy in HCV-related mixed cryoglobulinemia

| Author | Year | No. patients | Treatment | CS | Treatment duration (months) | EOT response | Sustained response |

| Durand | 1998 | 5 NR | RBV | No | 10-36 | 100% | 0% |

| Calleja | 1999 | 18 | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w | No | 12 | 55% | 28% |

| 8 NR | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w + RBV | No | 12 | 63% | 38% | ||

| Zuckerman | 2000 | 9 NR | 3 MIU IFN × 3/w + RBV | No | 6 | 78% | |

| Cacoub | 2002 | 14 | Variable IFN + RBV | variable | 6-56 | 71% | |

| Mazzaro | 2003 | 27 NR or Rel | 3 MIU × 3/w + RBV | No | 12 | 85% | |

| Alric | 2004 | 18 | 3 MIU × 3/w or Peg-IFN + RBV | No | ≥ 18 | 70% | |

| Cacoub | 2005 | 9 | Peg-IFN 1.5 μg Kg-1 w-1 + RBV | ≥ 10 | 88% | ||

| Mazzaro | 2005 | 18 | Peg-IFN 1 μg Kg-1 w-1 + RBV | No | 12 | 89% | 44% |

CS: corticosteroids; MIU: millions of international units; d: day; m: months; w: week; EOT: end of treatment; NR: non responders; Rel: relapser; RBV: ribavirin. From: Zignego A.L. Postgraduate Course of the 41st Annual Meeting of the EASL, 2006.

Interestingly, all available studies show that clinico-immunological and virologic response are generally strictly related[112,117,119,125-127]. In recent studies, persistence of isolated lymphatic infection after therapy was significantly associated with persistence of MCS stigmata[102]. By contrast, a long term clinical response was correlated with persistent HCV negativity of different compartments ([102], Zignego et al, submitted paper).

Disappearance of B-lymphocyte (BL) monoclonal infiltrate from bone marrow as well as BL expansion in peripheral blood following IFN therapy has been shown. In particular, the antiviral response was shown to be significantly related to the lack of detection of circulating B-cell clones bearing t(14;18) translocation[95,100,128] (see also above). The reappearance of circulating translocated BL clones after virological relapse at the end of treatment, as well as the persistent detection of t(14;18) positive clones in subjects with unmodified viral load after identical therapy, strongly indicates that clonal expansion of translocated cells depends on modifications of viral replication induced by antiviral treatment[100,128]. More recently, long-term analysis of HCV + MCS patients showing SVR after therapy (see above) indicated that occult lymphatic infection and persistence of MCS stigmata were also associated with persistent determination of expanded t(14;18) carrying B-cell clones ([102], and Zignego et al, submitted paper). Altogether the current data suggest that IFN treatment, when successful, may also help in preventing the evolution of HCV-related LPDs.

In conclusion, the available data concerning antiviral treatment of MCS show that this therapeutic approach should be the first option because of the antiproliferative and immunomudulatory effects of IFN, the usefulness of antiviral therapy as demonstrated in most available studies, the strict correlation between virological and clinical response, as well as the positive effect of inhibition of viral replication on B-cell clonal expansion that is considered the pathogenetic basis of MC. However, in comparison with antiviral treatment of HCV chronic liver disease, antiviral therapy of MCS is more complex for several reasons including the absence of standardized treatment protocols, the higher frequency of relapse, and generic or MCS-specific contraindications to antiviral treatment (i.e., advanced age, severe liver disease, acute nephritis, widespread vasculitis). In addition, the interpretation of results following IFN treatment in MCS patients seems to be much more complex than in MCS-negative chronic HCV infection. In fact, biochemical markers of MC response (cryocrit, RF or complement values) may be more independent of virological response than ALT levels. This may confirm the importance of a multiphase, complex, pathogenetic mechanism in MCS, suggesting the need for precise monitoring of this category of patients and the definition of predictive markers which indicate evolution towards pathogenetic phases of the disease. A possible candidate marker may be the evaluation of BL clonal expansion modifications in PBMC samples, as previously mentioned[95,100,101,128]; further studies are needed to better define its clinical value.

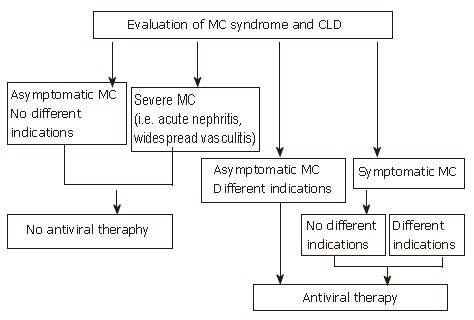

Figure 2 shows a suggested algorithm for treatment of HCV-related MCS with antiviral therapy. At present, antiviral therapy is suggested as the first choice treatment of this condition, to be performed even in the absence of different indications, with the exclusion of patients with only biochemical stigmata of MC (i.e., CGs). Particular attention should also be given to the treatment of severe MCS (i.e., patients with acute nephritis, widespread vasculitis). In these cases no sufficient data are available supporting the safety of IFN administration and a cautious attitude is strongly suggested. It is opportune to use alternative, more "traditional" therapeutic approaches in all patients in whom antiviral treatment is contraindicated or not tolerated or who are non-responders. Alternatives include corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, FANS, plasmapheresis and a hypo-antigenic diet[34,129]. Treatment should be tailored to the single patient, according to the severity of clinical symptoms, and considering the possible additional factors involved (age, co-morbidity etc.), and limited to the time (weeks or months) required for symptom remission. Any therapeutic approach aimed at improving serological parameters in clinically asymptomatic patients should be avoided.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for treatment of HCV-positive mixed cryoglobulinemia patients with antiviral therapy according to the evaluation of both mixed cryoglobulinemia syndrome and chronic liver damage. Available data suggest that antiviral therapy should be considered the first choice treatment in mixed cryoglobulinemia, to be performed even in the absence of different indications, excluding only those patients without symptoms and other indications or patients with too severe manifestations such as acute nephritis or widespread vasculitis. (Zignego AL, Postgraduate Course EASL 2006, Vienna and [34], modified)

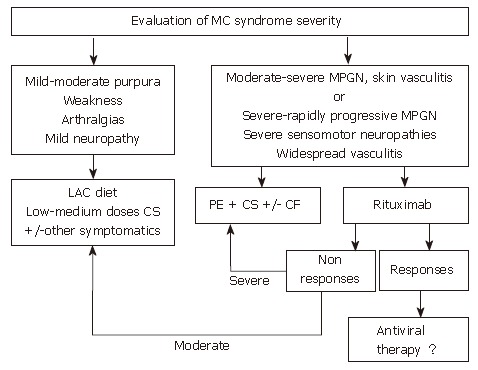

Corticosteroids are the most commonly used therapy for MCS before HCV identification due to the fact that, even at low doses, they can control the majority of MCS symptoms. On the other hand, corticosteroids may favor HCV replication, may cause several side effects, and do not induce significant modifications in the cryocrit levels or in the natural history of the disease. Cytostatic-immunosuppressive drugs (i.e., cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil and azathioprine) have been used mainly in the absence of response to corticosteroids and/or during the acute phases of MCS (i.e., acute nephritis evolving towards renal failure, hyperviscosity syndrome in association with plasmapheresis). These molecules generally have some severe side effects, including disease progression secondary to the relevant immunosuppressive effect[130]. A special note must be made of new B-cell specific immunosuppressive therapy based on the use of chimeric antibodies against the CD20, a B cell specific surface antigen (rituximab)[131,132]. Several studies showed that rituximab is effective in most patients with MC, leading to marked improvement or resolution of the syndrome - with particular reference to skin lesions - and regression of the expanded B-cell clones[131,132]. However, in spite of the fact that no immediate treatment-induced liver damage has been reported, this drug leads to an increase in HCV replication, explaining interest in its combination with antiviral molecules[34,131-134]. Overall, this therapeutic approach appears to be very promising in the management of MCS patients, however, future prospective, controlled, and randomized studies are still required to establish evidence-based guidelines to treat HCV-related MCS.

Other therapeutic measures are aimed at reducing CG concentration. These include plasmapheresis, and a LAC diet. Plasmapheresis represents the aphaeretic removal of CGs and circulating immunocomplexes. Because of its effectiveness and rapid action, it is especially indicated in the presence of acute manifestations (cryoglobulinemic nephritis, severe sensorimotor neuropathies, cutaneous ulcers, hyperviscosity syndrome). The association with cyclophosphamide has been shown to be effective in reducing the "rebound effect" at the end of aphaeresis. The LAC diet has a reduced content of alimentary macro-molecules with high antigenic properties allowing more efficient removal of CGs by the reticulo-endothelial system. This diet can improve minor manifestations of the disease (purpura, arthralgias, paresthesias), and is generally prescribed at the initial stage of the disease.

Figure 3 is a synthetic algorithm of the management of MCS, when etiological therapy is not possible or is ineffective.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for treatment of HCV-positive mixed cryoglobulinemia patients who are non-responders or in whom antiviral treatment is contraindicated or not tolerated. When antiviral treatment is not indicated this algorithm suggests other approaches for the management of mixed cryoglobulinemia, including anti-inflammatory drugs (first corticosteroids, CS), procedures able to lower the concentration of cryoglobulins such as the low antigen content (LAC) diet or plasma exchange (PE) as well as immunosuppressive drugs (cyclophosphamide, CF). In patients with only mild to moderate syndrome, cycles of therapy with anti-inflammatories, the LAC diet or other symptomatic treatments are suggested. Therapy should be adapted to the single patient and limited in time. In patients with more severe syndromes, cycles of plasma exchange plus corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive drugs are indicated. The use of rituximab, a selective B-cell suppressor, may be an alternative treatment in some cases where antiviral therapy is initially contraindicated. (Zignego AL, Postgraduate Course EASL 2006, Vienna and [34])

LYMPHOMA

In light of the above observations about MCS, the inclusion of antiviral therapy seems to be rational in therapeutic schemes for HCV-positive NHL. This appears to be confirmed by recent studies, performed in low-grade lymphoma[135] and, in particular, in marginal zone lymphomas[71,136]. Vallisa et al treated 13 patients with HCV-associated low-grade B-NHL characterized by an indolent course (i.e., doubling time no less than 1 year, no bulky disease) with pegylated IFN and ribavirin. Hematologic responses were observed in the majority of patients (complete and partial responses, 75%) and were highly significantly associated with clearance or decrease in serum HCV viral load following treatment, strongly providing a role for antiviral treatment in HCV-related, low-grade, B-cell NHL. Hermine et al showed that most patients with HCV and splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes (SLVL) entered complete remission upon treatment with IFN[71]. The inclusion of a control group integrated by patients with the same LPD but without HCV infection demonstrated that, in contrast with HCV-infected patients, HCV-negative subjects did not respond to IFN therapy, strongly suggesting that the response observed in HCV-positive patients was not merely due to the antiproliferative effect of IFN. Analogously, regression of clonal proli-feration in response to antiviral treatment was shown to be clearly associated with virological response[95,128]. Interestingly, also in HCV patients without evidence of LPD, a close association between the virological response and the loss of B-cell monoclonality with persistence of expanded t(14:18)-positive B-cell clones in non virological responders was shown, indicating that the more effective the antiviral therapy is, the more likely is loss of B-cell clonality[100].

Unfortunately, only some lymphomas may be cured with antiviral therapy. In addition, also in cases of re-sponsive SLVL, the rearrangement of the monoclonal immunoglobulin genes observed at diagnosis is still de-tectable in the blood even after a complete hematological response has been achieved[72]. These data suggest that the multi-step lymphomagenetic cascade is complicated by points of no return, making LPD more and more independent of HCV infection. Although antiviral therapy appears to be an attractive therapeutic tool for low-grade HCV-positive NHL, in intermediate and high-grade NHL, chemotherapy is expected to be necessary and antiviral treatment may be suggested as maintenance therapy after chemotherapy completion[137]. Further studies are needed to better standardize the antiviral therapy for HCV-related NHL patients.

The use of rituximab in HCV-associated NHL, in monotherapy or in combination with antiviral treatment and/or chemotherapy, appears very promising, especially in the setting of low-grade NHL, where rituximab monotherapy has been proposed as first-line treatment[138]. Interestingly, Hainsworth et al showed that the use of rituximab in low-grade NHL with scheduled maintenance at 6-mo intervals produced high overall and complete response rates and a longer progression-free survival than has been reported with a standard 4-wk treatment[138].

Few data are presently available specifically concerning patients with HCV-associated NHL. For example, Somer et al observed that after rituximab treatment a patient with Sjogren's syndrome (SS) and lymphoma showed improvement of parotidomegaly, ocular tests and salivary flow rate[139]. In addition, Ramos-Casals et al reported two patients with HCV-related SS who developed B-cell lymphoma and who responded successfully to treatment with rituximab[140].

In synthesis, in spite of the limited number of described cases, it appears reasonable to consider rituximab as a safe and effective therapy for HCV-related indolent B-cell lymphoma.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.Zignego AL, Bréchot C. Extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection: facts and controversies. J Hepatol. 1999;31:369–376. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cacoub P, Poynard T, Ghillani P, Charlotte F, Olivi M, Piette JC, Opolon P. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C. MULTIVIRC Group. Multidepartment Virus C. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2204–2212. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2204::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zignego AL, Ferri C, Pileri SA, Caini P, Bianchi FB. Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:2–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misiani R, Bellavita P, Fenili D, Borelli G, Marchesi D, Massazza M, Vendramin G, Comotti B, Tanzi E, Scudeller G. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, Palla P, Moretti A, Marzo E, Mazzoni A, Pasero G, Bombardieri S, Highfield P. Association between hepatitis C virus and mixed cryoglobulinemia [see comment] Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1991;9:621–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zignego AL, Ferri C, Giannini C, La Civita L, Careccia G, Longombardo G, Bellesi G, Caracciolo F, Thiers V, Gentilini P. Hepatitis C virus infection in mixed cryoglobulinemia and B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: evidence for a pathogenetic role. Arch Virol. 1997;142:545–555. doi: 10.1007/s007050050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agnello V, Chung RT, Kaplan LM. A role for hepatitis C virus infection in type II cryoglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1490–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211193272104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, Klein M, Seligmann M. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins. A report of 86 cases. Am J Med. 1974;57:775–788. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agnello V. Hepatitis C virus infection and type II cryoglobulinemia: an immunological perspective. Hepatology. 1997;26:1375–1379. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.ajhep0261375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lunel F, Musset L, Cacoub P, Frangeul L, Cresta P, Perrin M, Grippon P, Hoang C, Valla D, Piette JC. Cryoglobulinemia in chronic liver diseases: role of hepatitis C virus and liver damage. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1291–1300. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong VS, Egner W, Elsey T, Brown D, Alexander GJ. Incidence, character and clinical relevance of mixed cryoglobulinaemia in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:25–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawlotsky JM, Roudot-Thoraval F, Simmonds P, Mellor J, Ben Yahia MB, André C, Voisin MC, Intrator L, Zafrani ES, Duval J, et al. Extrahepatic immunologic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis C virus serotypes. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:169–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-3-199502010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferri C, Monti M, La Civita L, Longombardo G, Greco F, Pasero G, Gentilini P, Bombardieri S, Zignego AL. Infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by hepatitis C virus in mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1993;82:3701–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferri C, Sebastiani M, Giuggioli D, Cazzato M, Longombardo G, Antonelli A, Puccini R, Michelassi C, Zignego AL. Mixed cryoglobulinemia: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 231 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;33:355–374. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferri C, La Civita L, Cirafisi C, Siciliano G, Longombardo G, Bombardieri S, Rossi B. Peripheral neuropathy in mixed cryoglobulinemia: clinical and electrophysiologic investigations. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:889–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tembl JI, Ferrer JM, Sevilla MT, Lago A, Mayordomo F, Vilchez JJ. Neurologic complications associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Neurology. 1999;53:861–864. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lidove O, Cacoub P, Maisonobe T, Servan J, Thibault V, Piette JC, Léger JM. Hepatitis C virus infection with peripheral neuropathy is not always associated with cryoglobulinaemia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:290–292. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson RJ, Willson R, Yamabe H, Couser W, Alpers CE, Wener MH, Davis C, Gretch DR. Renal manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1255–1263. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daghestani L, Pomeroy C. Renal manifestations of hepatitis C infection. Am J Med. 1999;106:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Amico G. Renal involvement in hepatitis C infection: cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1998;54:650–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarantino A, Campise M, Banfi G, Confalonieri R, Bucci A, Montoli A, Colasanti G, Damilano I, D'Amico G, Minetti L. Long-term predictors of survival in essential mixed cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1995;47:618–623. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferri C, Marzo E, Longombardo G, Lombardini F, La Civita L, Vanacore R, Liberati AM, Gerli R, Greco F, Moretti A, et al. Interferon-alpha in mixed cryoglobulinemia patients: a randomized, crossover-controlled trial. Blood. 1993;81:1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cacoub P, Fabiani FL, Musset L, Perrin M, Frangeul L, Leger JM, Huraux JM, Piette JC, Godeau P. Mixed cryoglobulinemia and hepatitis C virus. Am J Med. 1994;96:124–132. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayali Z, Buckwold VE, Zimmerman B, Schmidt WN. Hepatitis C, cryoglobulinemia, and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;36:978–985. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.35620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saadoun D, Asselah T, Resche-Rigon M, Charlotte F, Bedossa P, Valla D, Piette JC, Marcellin P, Cacoub P. Cryoglobulinemia is associated with steatosis and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:1337–1345. doi: 10.1002/hep.21190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferri C, Zignego AL, Pileri SA. Cryoglobulins. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:4–13. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musset L, Diemert MC, Taibi F, Thi Huong Du L, Cacoub P, Leger JM, Boissy G, Gaillard O, Galli J. Characterization of cryoglobulins by immunoblotting. Clin Chem. 1992;38:798–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sansonno D, De Vita S, Iacobelli AR, Cornacchiulo V, Boiocchi M, Dammacco F. Clonal analysis of intrahepatic B cells from HCV-infected patients with and without mixed cryoglobulinemia. J Immunol. 1998;160:3594–3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magalini AR, Facchetti F, Salvi L, Fontana L, Puoti M, Scarpa A. Clonality of B-cells in portal lymphoid infiltrates of HCV-infected livers. J Pathol. 1998;185:86–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199805)185:1<86::AID-PATH59>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Racanelli V, Sansonno D, Piccoli C, D'Amore FP, Tucci FA, Dammacco F. Molecular characterization of B cell clonal expansions in the liver of chronically hepatitis C virus-infected patients. J Immunol. 2001;167:21–29. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallat L, Benhamou Y, Gutierrez M, Ghillani P, Hercher C, Thibault V, Charlotte F, Piette JC, Poynard T, Merle-Béral H, et al. Clonal B cell populations in the blood and liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3668–3678. doi: 10.1002/art.20594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monteverde A, Pileri S. Lymphoproliferative diseases of uncertain classification. Ann Ital Med Int. 1991;6:162–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferri C, Pileri S, Zignego AL. Hepatitis C virus infection and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. In: Geodert J, (NIH) NCI, eds , editors. Infectious causes of cancer Targets for intervention. Totowa, New Jersey: The Human Press inc; 2000. pp. 349–368. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferri C, Zignego AL, Pileri SA. Cryoglobulinemia. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santini GF, Crovatto M, Modolo ML, Martelli P, Silvia C, Mazzi G, Franzin F, Moretti M, Tulissi P, Pozzato G. Waldenström macroglobulinemia: a role of HCV infection? Blood. 1993;82:2932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pozzato G, Mazzaro C, Crovatto M, Modolo ML, Ceselli S, Mazzi G, Sulfaro S, Franzin F, Tulissi P, Moretti M. Low-grade malignant lymphoma, hepatitis C virus infection, and mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1994;84:3047–3053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mussini C, Ghini M, Mascia MT, Giovanardi P, Zanni G, Lattuada I, Moreali S, Longo G, Ferrari MG, Torelli G. Monoclonal gammopathies and hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 1995;85:1144–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangia A, Clemente R, Musto P, Cascavilla I, La Floresta P, Sanpaolo G, Gentile R, Viglotti ML, Facciousso D, Carotenuto M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and monoclonal gammopathies not associated with cryoglobulinemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:1209–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musto P, Dell'Olio M, Carotenuto M, Mangia A, Andriulli A. Hepatitis C virus infection: a new bridge between hematologists and gastroenterologists? Blood. 1996;88:752–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silvestri F, Barillari G, Fanin R, Salmaso F, Pipan C, Falasca E, Puglisi F, Mariuzzi L, Zaja F, Infanti L, et al. Impact of hepatitis C virus infection on clinical features, quality of life and survival of patients with lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma/immunocytoma. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:499–504. doi: 10.1023/a:1008265804550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferri C, Monti M, La Civita L, Careccia G, Mazzaro C, Longombardo G, Lombardini F, Greco F, Pasero G, Bombardieri S. Hepatitis C virus infection in non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphoma complicating mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24:781–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monti G, Pioltelli P, Saccardo F, Campanini M, Candela M, Cavallero G, De Vita S, Ferri C, Mazzaro C, Migliaresi S, et al. Incidence and characteristics of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in a multicenter case file of patients with hepatitis C virus-related symptomatic mixed cryoglobulinemias. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:101–105. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferri C, Caracciolo F, La Civita L, Monti M, Longombardo G, Greco F, Zignego AL. Hepatitis C virus infection and B-cell lymphomas. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1591–1592. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferri C, La Civita L, Caracciolo F, Zignego AL. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: possible role of hepatitis C virus. JAMA. 1994;272:355–356. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520050033023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferri C, Caracciolo F, Zignego AL, La Civita L, Monti M, Longombardo G, Lombardini F, Greco F, Capochiani E, Mazzoni A. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 1994;88:392–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazzaro C, Zagonel V, Monfardini S, Tulissi P, Pussini E, Fanni M, Sorio R, Bortolus R, Crovatto M, Santini G, et al. Hepatitis C virus and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:544–550. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.6912313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luppi M, Grazia Ferrari M, Bonaccorsi G, Longo G, Narni F, Barozzi P, Marasca R, Mussini C, Torelli G. Hepatitis C virus infection in subsets of neoplastic lymphoproliferations not associated with cryoglobulinemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pioltelli P, Zehender G, Monti G, Monteverde A, Galli M. HCV and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 1996;347:624–625. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silvestri F, Pipan C, Barillari G, Zaja F, Fanin R, Infanti L, Russo D, Falasca E, Botta GA, Baccarani M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 1996;87:4296–4301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuckerman E, Zuckerman T, Levine AM, Douer D, Gutekunst K, Mizokami M, Qian DG, Velankar M, Nathwani BN, Fong TL. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:423–428. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-6-199709150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silvestri F, Barillari G, Fanin R, Pipan C, Falasca E, Salmaso F, Zaja F, Infanti L, Patriarca F, Botta GA, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among cryoglobulinemic and non-cryoglobulinemic B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Haematologica. 1997;82:314–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Izumi T, Sasaki R, Tsunoda S, Akutsu M, Okamoto H, Miura Y. B cell malignancy and hepatitis C virus infection. Leukemia. 1997;11 Suppl 3:516–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mele A, Pulsoni A, Bianco E, Musto P, Szklo A, Sanpaolo MG, Iannitto E, De Renzo A, Martino B, Liso V, et al. Hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas: an Italian multicenter case-control study. Blood. 2003;102:996–999. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsuo K, Kusano A, Sugumar A, Nakamura S, Tajima K, Mueller NE. Effect of hepatitis C virus infection on the risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:745–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brind AM, Watson JP, Burt A, Kestevan P, Wallis J, Proctor SJ, Bassendine MF. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and hepatitis C virus infection. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;21:127–130. doi: 10.3109/10428199609067589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanley J, Jarvis L, Simmonds P, Parker A, Ludlam C. HCV and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 1996;347:1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McColl MD, Singer IO, Tait RC, McNeil IR, Cumming RL, Hogg RB. The role of hepatitis C virus in the aetiology of non-Hodgkins lymphoma--a regional association? Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26:127–130. doi: 10.3109/10428199709109167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ellenrieder V, Weidenbach H, Frickhofen N, Michel D, Prümmer O, Klatt S, Bernas O, Mertens T, Adler G, Beckh K. HCV and HGV in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Hepatol. 1998;28:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collier JD, Zanke B, Moore M, Kessler G, Krajden M, Shepherd F, Heathcote J. No association between hepatitis C and B-cell lymphoma. Hepatology. 1999;29:1259–1261. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hausfater P, Cacoub P, Rosenthal E, Bernard N, Loustaud-Ratti V, Le Lostec Z, Laurichesse H, Turpin F, Ouzan D, Grasset D, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and lymphoproliferative diseases in France: a national study. The GERMIVIC Group. Am J Hematol. 2000;64:107–111. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(200006)64:2<107::aid-ajh6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silvestri F, Baccarani M. Hepatitis C virus-related lymphomas. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:475–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.4023216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Vita S, Sacco C, Sansonno D, Gloghini A, Dammacco F, Crovatto M, Santini G, Dolcetti R, Boiocchi M, Carbone A, et al. Characterization of overt B-cell lymphomas in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 1997;90:776–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ascoli V, Lo Coco F, Artini M, Levrero M, Martelli M, Negro F. Extranodal lymphomas associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;109:600–609. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/109.5.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luppi M, Longo G, Ferrari MG, Barozzi P, Marasca R, Morselli M, Valenti C, Mascia T, Vandelli L, Vallisa D, et al. Clinico-pathological characterization of hepatitis C virus-related B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas without symptomatic cryoglobulinemia. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:495–498. doi: 10.1023/a:1008255830453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trépo C, Berthillon P, Vitvitski L. HCV and lymphoproliferative diseases. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:469–470. doi: 10.1023/a:1008298228620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Talamini R, Montella M, Crovatto M, Dal Maso L, Crispo A, Negri E, Spina M, Pinto A, Carbone A, Franceschi S. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and hepatitis C virus: a case-control study from northern and southern Italy. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:380–385. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, Gatter KC. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jaffe ES HN, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Vita S, Sansonno D, Dolcetti R, Ferraccioli G, Carbone A, Cornacchiulo V, Santini G, Crovatto M, Gloghini A, Dammacco F, et al. Hepatitis C virus within a malignant lymphoma lesion in the course of type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1995;86:1887–1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luppi M, Longo G, Ferrari MG, Ferrara L, Marasca R, Barozzi P, Morselli M, Emilia G, Torelli G. Additional neoplasms and HCV infection in low-grade lymphoma of MALT type. Br J Haematol. 1996;94:373–375. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hermine O, Lefrère F, Bronowicki JP, Mariette X, Jondeau K, Eclache-Saudreau V, Delmas B, Valensi F, Cacoub P, Brechot C, et al. Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:89–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saadoun D, Suarez F, Lefrere F, Valensi F, Mariette X, Aouba A, Besson C, Varet B, Troussard X, Cacoub P, et al. Splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes, associated with type II cryoglobulinemia and HCV infection: a new entity? Blood. 2005;105:74–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andreone P, Zignego AL, Cursaro C, Gramenzi A, Gherlinzoni F, Fiorino S, Giannini C, Boni P, Sabattini E, Pileri S, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathies in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:294–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-4-199808150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bartl R, Frisch B, Fateh-Moghadam A, Kettner G, Jaeger K, Sommerfeld W. Histologic classification and staging of multiple myeloma. A retrospective and prospective study of 674 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:342–355. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/87.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pileri S, Poggi S, Baglioni P, Montanari M, Sabattini E, Galieni P, Tazzari PL, Gobbi M, Cavo M, Falini B. Histology and immunohistology of bone marrow biopsy in multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol Suppl. 1989;51:52–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1989.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zignego AL, Ferri C, Monti M, LaCivita L, Giannini C, Careccia G, Giannelli F, Pasero G, Bombardieri S, Gentilini P. Hepatitis C virus as a lymphotropic agent: evidence and pathogenetic implications. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13 Suppl 13:S33–S37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zignego AL, Macchia D, Monti M, Thiers V, Mazzetti M, Foschi M, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Gentilini P, Bréchot C. Infection of peripheral mononuclear blood cells by hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol. 1992;15:382–386. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zignego AL, De Carli M, Monti M, Careccia G, La Villa G, Giannini C, D'Elios MM, Del Prete G, Gentilini P. Hepatitis C virus infection of mononuclear cells from peripheral blood and liver infiltrates in chronically infected patients. J Med Virol. 1995;47:58–64. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shimizu YK, Igarashi H, Kanematu T, Fujiwara K, Wong DC, Purcell RH, Yoshikura H. Sequence analysis of the hepatitis C virus genome recovered from serum, liver, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infected chimpanzees. J Virol. 1997;71:5769–5773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5769-5773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bronowicki JP, Loriot MA, Thiers V, Grignon Y, Zignego AL, Bréchot C. Hepatitis C virus persistence in human hematopoietic cells injected into SCID mice. Hepatology. 1998;28:211–218. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lerat H, Rumin S, Habersetzer F, Berby F, Trabaud MA, Trépo C, Inchauspé G. In vivo tropism of hepatitis C virus genomic sequences in hematopoietic cells: influence of viral load, viral genotype, and cell phenotype. Blood. 1998;91:3841–3849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roque Afonso AM, Jiang J, Penin F, Tareau C, Samuel D, Petit MA, Bismuth H, Dussaix E, Féray C. Nonrandom distribution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell subsets. J Virol. 1999;73:9213–9221. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9213-9221.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sansonno D, Lotesoriere C, Cornacchiulo V, Fanelli M, Gatti P, Iodice G, Racanelli V, Dammacco F. Hepatitis C virus infection involves CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells in hepatitis C virus chronic carriers. Blood. 1998;92:3328–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roque-Afonso AM, Ducoulombier D, Di Liberto G, Kara R, Gigou M, Dussaix E, Samuel D, Féray C. Compartmentalization of hepatitis C virus genotypes between plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 2005;79:6349–6357. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6349-6357.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Galli M, Zehender G, Monti G, Ballaré M, Saccardo F, Piconi S, De Maddalena C, Bertoncelli MC, Rinaldi G, Invernizzi F. Hepatitis C virus RNA in the bone marrow of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia and in subjects with noncryoglobulinemic chronic hepatitis type C. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:672–675. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pal S, Sullivan DG, Kim S, Lai KK, Kae J, Cotler SJ, Carithers RL, Wood BL, Perkins JD, Gretch DR. Productive replication of hepatitis C virus in perihepatic lymph nodes in vivo: implications of HCV lymphotropism. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1107–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ivanovski M, Silvestri F, Pozzato G, Anand S, Mazzaro C, Burrone OR, Efremov DG. Somatic hypermutation, clonal diversity, and preferential expression of the VH 51p1/VL kv325 immunoglobulin gene combination in hepatitis C virus-associated immunocytomas. Blood. 1998;91:2433–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De Re V, De Vita S, Marzotto A, Rupolo M, Gloghini A, Pivetta B, Gasparotto D, Carbone A, Boiocchi M. Sequence analysis of the immunoglobulin antigen receptor of hepatitis C virus-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas suggests that the malignant cells are derived from the rheumatoid factor-producing cells that occur mainly in type II cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2000;96:3578–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sansonno D, Lauletta G, De Re V, Tucci FA, Gatti P, Racanelli V, Boiocchi M, Dammacco F. Intrahepatic B cell clonal expansions and extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV infection. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:126–136. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mariette X. Lymphomas complicating Sjögren's syndrome and hepatitis C virus infection may share a common pathogenesis: chronic stimulation of rheumatoid factor B cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1007–1010. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, Weiner AJ, Houghton M, Rosa D, Grandi G, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Machida K, Cheng KT, Sung VM, Shimodaira S, Lindsay KL, Levine AM, Lai MY, Lai MM. Hepatitis C virus induces a mutator phenotype: enhanced mutations of immunoglobulin and protooncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4262–4267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303971101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zignego AL, Giannelli F, Marrocchi ME, Giannini C, Gentilini P, Innocenti F, Ferri C. Frequency of bcl-2 rearrangement in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia and HCV-positive liver diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1997;15:711–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zignego AL, Giannelli F, Marrocchi ME, Mazzocca A, Ferri C, Giannini C, Monti M, Caini P, Villa GL, Laffi G, et al. T(14; 18) translocation in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2000;31:474–479. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zignego AL, Ferri C, Giannelli F, Giannini C, Caini P, Monti M, Marrocchi ME, Di Pietro E, La Villa G, Laffi G, et al. Prevalence of bcl-2 rearrangement in patients with hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia with or without B-cell lymphomas. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:571–580. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kitay-Cohen Y, Amiel A, Hilzenrat N, Buskila D, Ashur Y, Fejgin M, Gaber E, Safadi R, Tur-Kaspa R, Lishner M. Bcl-2 rearrangement in patients with chronic hepatitis C associated with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia type II. Blood. 2000;96:2910–2912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zuckerman E, Zuckerman T, Sahar D, Streichman S, Attias D, Sabo E, Yeshurun D, Rowe J. bcl-2 and immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:364–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sasso EH, Martinez M, Yarfitz SL, Ghillani P, Musset L, Piette JC, Cacoub P. Frequent joining of Bcl-2 to a JH6 gene in hepatitis C virus-associated t(14; 18) J Immunol. 2004;173:3549–3556. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Libra M, Gloghini A, Navolanic PM, Zignego AL, De Re V, Carbone A. JH6 gene usage among HCV-associated MALT lymphomas harboring t(14; 18) translocation. J Immunol. 2005;174:3839; author reply 3839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Giannelli F, Moscarella S, Giannini C, Caini P, Monti M, Gragnani L, Romanelli RG, Solazzo V, Laffi G, La Villa G, et al. Effect of antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HCV infection and t(14; 18) translocation. Blood. 2003;102:1196–1201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mazzaro C, Franzin F, Tulissi P, Pussini E, Crovatto M, Carniello GS, Efremov DG, Burrone O, Santini G, Pozzato G. Regression of monoclonal B-cell expansion in patients affected by mixed cryoglobulinemia responsive to alpha-interferon therapy. Cancer. 1996;77:2604–2613. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960615)77:12<2604::AID-CNCR26>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Giannini C, Giannelli F, Zignego AL. Association between mixed cryoglobulinemia, translocation (14; 18), and persistence of occult HCV lymphoid infection after treatment. Hepatology. 2006;43:1166–1167; author reply 1167-1168. doi: 10.1002/hep.21132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fornasieri A, Bernasconi P, Ribero ML, Sinico RA, Fasola M, Zhou J, Portera G, Tagger A, Gibelli A, D'amico G. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) in lymphocyte subsets and in B lymphocytes expressing rheumatoid factor cross-reacting idiotype in type II mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:400–403. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bonomo L, Casato M, Afeltra A, Caccavo D. Treatment of idiopathic mixed cryoglobulinemia with alpha interferon. Am J Med. 1987;83:726–730. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Casato M, Laganà B, Antonelli G, Dianzani F, Bonomo L. Long-term results of therapy with interferon-alpha for type II essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1991;78:3142–3147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ferri C, Zignego AL, Longombardo G, Monti M, La Civita L, Lombardini F, Greco F, Mazzoni A, Pasero G, Gentilini P. Effect of alpha-interferon on hepatitis C virus chronic infection in mixed cryoglobulinemia patients. Infection. 1993;21:93–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01710739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marcellin P, Descamps V, Martinot-Peignoux M, Larzul D, Xu L, Boyer N, Pham BN, Crickx B, Guillevin L, Belaich S. Cryoglobulinemia with vasculitis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:272–277. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Yamabe H, Hart J, Bacchi CE, Hartwell P, Couser WG, Corey L, Wener MH, Alpers CE. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:465–470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Misiani R, Bellavita P, Fenili D, Vicari O, Marchesi D, Sironi PL, Zilio P, Vernocchi A, Massazza M, Vendramin G. Interferon alfa-2a therapy in cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis C virus. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:751–756. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403173301104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dammacco F, Sansonno D, Han JH, Shyamala V, Cornacchiulo V, Iacobelli AR, Lauletta G, Rizzi R. Natural interferon-alpha versus its combination with 6-methyl-prednisolone in the therapy of type II mixed cryoglobulinemia: a long-term, randomized, controlled study. Blood. 1994;84:3336–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Couser WG, Alpers CE, Wilson J, Chung M, Hart J, Willson R. Hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis. Effect of alpha-interferon therapy. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1700–1704. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mazzaro C, Pozzato G, Moretti M, Crovatto M, Modolo ML, Mazzi G, Santini G. Long-term effects of alpha-interferon therapy for type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Haematologica. 1994;79:342–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Casaril M, Capra F, Gabrielli GB, Bassi A, Squarzoni S, Dagradi R, De Maria E, Corrocher R. Cryoglobulinemia in hepatitis C virus chronic active hepatitis: effects of interferon-alpha therapy. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16:585–588. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cohen P, Nguyen QT, Dény P, Ferrière F, Roulot D, Lortholary O, Jarrousse B, Danon F, Barrier JH, Ceccaldi J, et al. Treatment of mixed cryoglobulinemia with recombinant interferon alpha and adjuvant therapies. A prospective study on 20 patients. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1996;147:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Akriviadis EA, Xanthakis I, Navrozidou C, Papadopoulos A. Prevalence of cryoglobulinemia in chronic hepatitis C virus infection and response to treatment with interferon-alpha. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:612–618. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199712000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Casato M, Agnello V, Pucillo LP, Knight GB, Leoni M, Del Vecchio S, Mazzilli C, Antonelli G, Bonomo L. Predictors of long-term response to high-dose interferon therapy in type II cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 1997;90:3865–3873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Calleja JL, Albillos A, Moreno-Otero R, Rossi I, Cacho G, Domper F, Yebra M, Escartín P. Sustained response to interferon-alpha or to interferon-alpha plus ribavirin in hepatitis C virus-associated symptomatic mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1179–1186. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zuckerman E, Keren D, Slobodin G, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Toubi E, Sabo E, Tsykounov I, Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D. Treatment of refractory, symptomatic, hepatitis C virus related mixed cryoglobulinemia with ribavirin and interferon-alpha. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2172–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cacoub P, Lidove O, Maisonobe T, Duhaut P, Thibault V, Ghillani P, Myers RP, Leger JM, Servan J, Piette JC. Interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C virus-related systemic vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3317–3326. doi: 10.1002/art.10699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mazzaro C, Zorat F, Comar C, Nascimben F, Bianchini D, Baracetti S, Donada C, Donadon V, Pozzato G. Interferon plus ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus positive mixed cryoglobulinemia resistant to interferon. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1775–1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heagy W, Crumpacker C, Lopez PA, Finberg RW. Inhibition of immune functions by antiviral drugs. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1916–1924. doi: 10.1172/JCI115217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Durand JM, Cacoub P, Lunel-Fabiani F, Cosserat J, Cretel E, Kaplanski G, Frances C, Bletry O, Soubeyrand J, Godeau P. Ribavirin in hepatitis C related cryoglobulinemia. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1115–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jaccard A, Loustaud V, Turlure P, Rogez S, Bordessoule D. Ribavirin and immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Lancet. 1998;351:1660–1661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Alric L, Plaisier E, Thébault S, Péron JM, Rostaing L, Pourrat J, Ronco P, Piette JC, Cacoub P. Influence of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus-associated cryoglobulinemic MPGN. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:617–623. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cacoub P, Saadoun D, Limal N, Sene D, Lidove O, Piette JC. PEGylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C virus-related systemic vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:911–915. doi: 10.1002/art.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Mazzaro C, Zorat F, Caizzi M, Donada C, Di Gennaro G, Maso LD, Carniello G, Virgolini L, Tirelli U, Pozzato G. Treatment with peg-interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin of hepatitis C virus-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia: a pilot study. J Hepatol. 2005;42:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Levine JW, Gota C, Fessler BJ, Calabrese LH, Cooper SM. Persistent cryoglobulinemic vasculitis following successful treatment of hepatitis C virus. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1164–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zuckerman E, Zuckerman T, Sahar D, Streichman S, Attias D, Sabo E, Yeshurun D, Rowe JM. The effect of antiviral therapy on t(14; 18) translocation and immunoglobulin gene rearrangement in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Blood. 2001;97:1555–1559. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ferri C, Giuggioli D, Cazzato M, Sebastiani M, Mascia MT, Zignego AL. HCV-related cryoglobulinemic vasculitis: an update on its etiopathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S78–S84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ballarè M, Bobbio F, Poggi S, Bordin G, Bertoncelli MC, Catania E, Monteverde A. A pilot study on the effectiveness of cyclosporine in type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13 Suppl 13:S201–S203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zaja F, De Vita S, Mazzaro C, Sacco S, Damiani D, De Marchi G, Michelutti A, Baccarani M, Fanin R, Ferraccioli G. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 2003;101:3827–3834. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sansonno D, De Re V, Lauletta G, Tucci FA, Boiocchi M, Dammacco F. Monoclonal antibody treatment of mixed cryoglobulinemia resistant to interferon alpha with an anti-CD20. Blood. 2003;101:3818–3826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zaja F, Russo D, Fuga G, Patriarca F, Ermacora A, Baccarani M. Rituximab for the treatment of type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Haematologica. 1999;84:1157–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zaja F, De Vita S, Russo D, Michelutti A, Fanin R, Ferraccioli G, Baccarani M. Rituximab for the treatment of type II mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2252–2254; author reply 2254-2255;. doi: 10.1002/art.10345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Vallisa D, Bernuzzi P, Arcaini L, Sacchi S, Callea V, Marasca R, Lazzaro A, Trabacchi E, Anselmi E, Arcari AL, et al. Role of anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment in HCV-related, low-grade, B-cell, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter Italian experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:468–473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kelaidi C, Rollot F, Park S, Tulliez M, Christoforov B, Calmus Y, Podevin P, Bouscary D, Sogni P, Blanche P, et al. Response to antiviral treatment in hepatitis C virus-associated marginal zone lymphomas. Leukemia. 2004;18:1711–1716. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gisbert JP, García-Buey L, Pajares JM, Moreno-Otero R. Systematic review: regression of lymphoproliferative disorders after treatment for hepatitis C infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:653–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]