Abstract

In recent years, great progress has been made regarding the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly in the field of biological therapies. Nevertheless, the ultimate treatment is not in sight. With the development of new medication, it has become clear that we need a new understanding of IBD. Therapy needs to fit the different subtypes of IBD; e.g. mild disease in comparison to severe chronic active disease or Crohn's disease with or without fistulation or stenosis. The following article gives a practical overview of actual treatments for IBD. The intention of this article is not to provide a complete review of all new scientific developments, but to give a practical guideline for therapy of IBD.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, Immunomodulators, Anti-tumor necrosis factor

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are both defined as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), characterized by a chronic inflammation of the gut mucosa. The clinical course of both diseases can differ from a mild form, in which the patient reaches long-term remission without taking permanent medication, to a chronic active form, in which remission is only reached by permanently taking immunosuppressives and/or biologics or by taking them for a long period of time. Patients are not only burdened by the most common symptoms of IBDs; e.g. diarrhea, bowel pain, fever and complications such as fistulation, stenosis and abscesses in Crohn's disease and megacolon in ulcerative colitis, but are also burdened by the side-effects of the therapeutics, which the patients take to achieve a normal quality of life. Therefore, it is a great responsibility for a physician to consider treatment for an individual patient.

Recent discussions in the field of IBD are concerned with recommendations for a step-down or step-up therapy. A step-down therapy means using the most effective biologic or immunosuppressive treatment on the market, even without prior use of therapeutics such as steroids, in order to reach an effective remission as soon as possible. A step-up therapy means using a “classical” treatment by, for example, starting with aminosalicylates and ending up with an immunosuppressive and/or biological. Even if using a common step-up therapy treatment, the decision about which drug to use should be based on the individual patient, considering the clinical course and diagnosed complications according to current treatment guidelines.

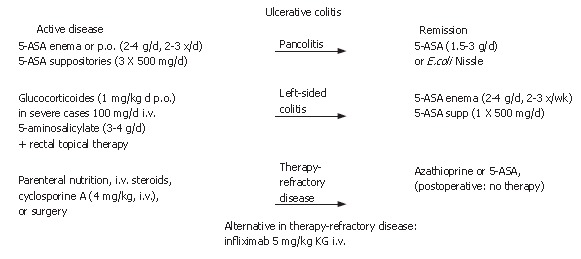

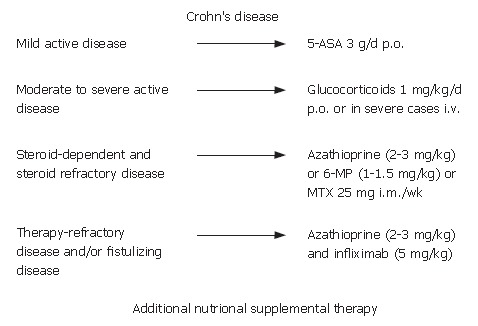

This article provides a short overview of IBD and practical guidelines for the actual treatment of IBD (Figures 1 and 2). It is recognized that there is still an urgent medical need for improvement in the treatment in IBD and that treatments may not be sufficient for all patients, although great progress has been made in therapeutic approaches in the last decades (especially regarding biological therapeutics). The current guidelines for IBD therapy are distinguished by the course, place and severity of the clinical disease[1-7]. In Crohn’s disease, a mild active form, a moderate or severe active form or a severe chronically active form can be differentiated. Patients can also be defined as steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory. The endoscopic and clinical pattern, the segments of the body that are involved (e.g. only small colon or small and large colon and/or stomach), the complications (such as fistulation and/or stenosis) as well as the duration of the inflammation and the response (or loss of response) to steroids are taken into account in the evaluation. In ulcerative colitis, differentiation is easier because inflammation only involves the large colon, starting from the rectum to the coecum. Therefore, treatment is determined by the clinical disease course and the involved segments of the colon, such as left-sided disease or pancolitis, as well as the response to steroids (steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory). In the following paragraphs the treatment of IBD will be discussed according to use of different therapeutic drugs.

Figure 1.

Short overview of the treatment regime of ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.

Short overview of treatment regimen in Crohn´s disease.

5-Aminosalicylates (5-ASA)

5-ASA are bowel-specific drugs that are metabolized in the gut where the predominant actions occur. As a derivative of salicylic acid, 5-ASA is also an antioxidant that traps free radicals, which are potentially damaging by-products of metabolism. In the radical induction theory of ulcerative colitis, 5-ASA functions as a free radical trap as well as an anti-inflammatory drug. 5-ASA is considered to be the active moiety of sulphasalazine, which metabolizes to it. Oral and/or topical 5-ASA is recommended for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis to induce and maintain remission. The dosage of 5-ASA should be no less than 3 g/d. In practice, most patients do not like a topical treatment, but in left-sided disease, an enema with 4 g of 5-ASA 2 times per day or suppositories with 500 mg 5-ASA 3 times per day are most effective. Sometimes it is helpful for the patient to use the enema only in the evening and the suppositories in the morning. In Crohn’s disease, aminosalicylates should also be used in initial therapy for mild disease, although discussion about efficacy has increased recently. In contrast to ulcerative colitis, the use of aminosalicylates for the maintenance of remission is not recommended for Crohn’s disease because clinical studies have not shown success in remission maintenance[8,9]. 5-ASA is a standard treatment for ulcerative colitis, but not for Crohn’s disease. In the last few years, new formulations have been on the market with varying clinical value. In some special cases; e.g. patients with an ileostoma, a formulation that sets metabolites free prior to the large bowel may be helpful. In patients with IBD and arthritis, sulphasalazine rather than 5-ASA formulations seems to be more effective regarding arthritis. In most patients, the side-effects are not very severe with headache as one of the most common side-effects. However, in some cases nephritis, pancreatitis and hair loss have been reported, which suggests regular monitoring of renal and liver enzymes at least once in three months.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics (e.g. metronidazole) play only a minor role in the additional treatment of fistulizing disease[10]. Although metronidazole (for up to 3 mo in a dosage of 400 mg 2 times per day) is often used in post-operative management after an ileocecal resection or fistula/abscess operation for Crohn’s disease, this therapy is not based on study evidence. A side-effect of long-term treatment with metronidazole is polyneuropathy and monitoring is, therefore, required. Antibiotics are also used in the conservative treatment of small abscesses. Understanding the role of microbiota and antibiotics in IBD may become important in the future, but currently clinical studies have not provided support for this concern.

Corticosteroids

In patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, corticosteroids are effective for the induction of clinical response and remission[11-16]. Dosages from 40-60 mg/d or 1 mg/kg per day orally are effective for the induction of remission. After the induction of remission, the steroid dose should be tapered (10 mg/wk until 40 mg; 5 mg/wk until 20 mg, followed by a tapering of 2.5 mg/wk). In severe disease, the application of parenteral glucocorticoids as soon as possible is useful for an anti-inflammatory response. Before the initiation of steroid treatment, the presence of an abscess should be excluded. In patients who have been on glucocorticoids for more than one month, an ACTH (Adrenocorticotropic hormone)-Test should be performed before beginning tapering of the steroid. The ACTH-test can detect deficient cortisol production in the body. If there is a deficiency, hydrocortisone should be used as a substitute.

Budesonide

The benefits of glucocorticoid therapy should be carefully balanced against possible side-effects. Budesonide can reduce typical steroid side effects by a 90% first-pass metabolism in the liver and erythrocytes. Due to a special structural formulation, budesonide achieves the best anti-inflammatory effect in ileocecal inflammation[17-20]. Therefore, it is useful in therapy for Crohn’s disease with ileocecal inflammation only. However, neither budesonide nor any other glucocorticosteroid should be used for a maintenance therapy due to the side-effects (e.g. Cushing-syndrome, osteoporosis or cardiomyopathy[21,22]). All patients treated with corticosteroids should additionally receive vitamin D and calcium substitution to avoid bone loss.

Immunosuppressives

The clinical course of 36% of IBD patients is defined as steroid-refractory and in 20% as steroid-dependent[23]. Immunomodulators are, therefore, recommended for the treatment of chronic active IBD. Studies have shown an efficacy for immunosuppressives that is similar to azathioprine and its metabolite, 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP; 2-3 mg/kg per day, resp. 1-1.5 mg/kg per day), in the long-term use of chronic active disease. Immunomodulators have been shown to be efficient for the control of inflammation and remission maintenance. Only limited data exists on the efficacy of immunosuppressants in fistulizing Crohn’s disease and the prevention of post-operative recurrence[24-30]. Evidence-based data is missing on the post-operative use of azathioprine and many IBD referral centers are using azathioprine for the prevention of post-operative recurrence. Prior to an initiation of treatment with azathioprine or 6-MP, patients should be thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) genotype assessed in order to detect for a homozygous deficiency in TPMT in an effort to avert AZA or 6-MP-induced potential adverse events. All patients on azathioprine or 6-MP should be monitored weekly in the first month and after that once a month regarding their white blood count and liver enzymes because a myelosuppression or an elevation of liver enzymes subsequent to the use of azathioprine or 6-MP can occur. In such cases, the dosage of azathioprine or 6-MP should be reduced or paused until lab values are normal. In patients with gastrointestinal side-effects after the intake of azathioprine, a change to 6-MP should be considered.

Methotrexate and cyclosporine

Methotrexate is another immunomodulatory agent that is used in long-term treatment of IBD. The dosage for induction of remission in chronic active disease is 25 mg i.m. per week for 16 wk, followed by a maintenance treatment of 15 mg i.m. per week. In contrast to azathioprine and 6-MP, the data on use of methotrexate is rather scarce[31-33]. Cyclosporine is reserved for the treatment of severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis only. Intravenous cyclosporine (2-4 mg/kg) was able to prevent a decidered colectomy in two of three patients with severe ulcerative colitis. Due to its toxicity, use should be considered carefully; i.e. it should be used only in very severe active disease cases to avoid a colectomy. In Crohn’s disease, cyclosporine has been shown to be effective only in fistulizing, but not luminal disease[34-37].

Tacrolimus

Only very inadequate data is available for tacrolimus. Improvement of fistula drainage, but not closure was demonstrated in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with tacrolimus[38,39].

Infliximab

Biological therapies, especially anti-TNF agents, play a pivotal role in the treatment of chronic active IBD and fistulizing disease[40-43]. The first anti-TNF agent on the market, infliximab, is a chimeric IgG1 mouse/human monoclonal antibody. Randomised, placebo-controlled trials (ACCENTIand II) demonstrated the efficacy of infliximab (5 mg/kg, i.v.) in the induction of clinical response and remission in patients with active Crohn´s disease. In fistulizing disease, complete fistula closure of at least 50% of the fistulas could be seen in 55% of the patients after three infusions of infliximab at wk 0, 2 and 6 (ACCENT II). Given on a regular basis in intervals of 8-12 wk (5 mg/kg i.v.), infliximab is able to maintain remission[44-50].

In ulcerative colitis, the recently completed ACTIand ACT II randomised, placebo-controlled trials demonstrated the efficacy of infliximab treatment in induction of remission and mucosal healing in 61.2% of the infliximab treated patients versus 32.4% of placebo treated patients[51,52].

Contraindications and side-effects should be taken into consideration carefully prior to infliximab therapy[53]. Due to immunogenicity, infliximab can lead to the formation of human anti-chimeric antibodies (HACA) in 30% to 75% of the patients. Additional administration of immunosuppressants; e.g. azathioprine and/or pretreatment with intravenous prednisolone, can reduce the risks of HACA formation. The main reported side-effect is an infusion reaction, which can occur as an acute allergic/anaphylactic reaction or a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. In clinical trials, observations have included infections, drug-induced lupus, cardiac failure, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and, in post-marketing surveillance, tuberculosis, pneumonia, histoplasmosis, listeriosis and aspergillosis. To avoid a potential tuberculosis reactivation, a purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test and a chest-X-ray should be performed prior to infliximab treatment[54-67].

Patients with perianal or enterocutaneous fistulizing Crohn’s disease should be treated first with infliximab. The effect of infliximab is not as effective on entero-enteral or recto-vaginal fistulas. Patients with steroid-refractory or chronic active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis who do not respond to immunosuppressive therapy alone should also be treated with infliximab. The recommended treatment regimen is an induction scheme with three infusions (5 mg/kg i.v.) at 0, 2 and 6 wk, followed by a maintenance treatment of infliximab every 8 wk (5 mg/kg i.v.). Additionally, immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine, for example, is recommended. HACA testing is not recommended routinely for every patient on infliximab, but it is recommended if there is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction or if the last infliximab infusion was more than 12 wk previous.

Adalimumab

Other TNF agents also showed efficacy in Crohn’s disease. The human IgG1 antibody adalimumab, which is a therapeutic agent used for rheumatoid arthritis, was effective in open-label experience. A placebo-controlled, randomised trial was also conducted. One advantage, in comparison to infliximab, might be the completely human structure of the antibody, which leads to better tolerance and a subcutaneous route of administration. Data on adverse reactions in Crohn’s disease patients are still not available, but adalimumab is well-tolerated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis[68-71].

CDP-870

Certolizumab pegol (CDP-870), which is a polyethylene-glycolated Fab-fragment of the anti-tumour necrosis factor, has been shown to be effective in the treatment of Crohn’s disease in a recent published, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. At week ten, 52.8% of the certolizumab (400 mg) treated patients showed a clinical response versus 30.1% in the placebo treated group (the high placebo response was seen in a large patient subgroup with low C-reactive protein levels; this might have been due to statistical separation between treatment and placebo group[72]). The antibody was well tolerated. Ongoing trials, however, are necessary to establish efficacy in Crohn’s disease.

CDP-571

CDP-571, which is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody against tumour necrosis factor alpha, initially showed an induction of clinical response in controlled trials, but failed in a phase III trial which was discontinued[73].

Onercept and eternacept

Onercept, which is a recombinant human p55 soluble receptor to TNF, and also eternacept, which is a recombinant human p75 soluble receptor to TNF, failed in a phase II trial with Crohn’s disease and both trials were discontinued[74-76].

Natalizumab

Adhesion molecule inhibiting agents, such as natalizumab, which is a humanized IgG4 antibody, demonstrated a clinical response in a clinical trial in Crohn’s disease, but all trials had to be stopped immediately after cases of progressive multifocal leucencephalopathy in patients receiving natalizumab for multiple sclerosis were reported[77-79].

The antisense oligonucleotide of the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 (anti-ICAM-1) was ineffective in Crohn’s disease[80].

A hopeful, novel approach for the treatment of Crohn’s disease is an anti-IL-12/IL-23p40 antibody that proved effective for induction of response and remission in a phase II study[81].

β-Interferon

The use of β-Interferon, which has been investigated in a small pilot study in ulcerative colitis with a subcutaneous administration, seems to be effective, but larger, randomised, placebo-controlled studies need to be performed to clarify the clinical efficacy[82].

In conclusion, the only biological therapeutic today, which has been proven effective in IBD and is available on the market is infliximab. The market release of new TNF agents might happen in the near future.

Probiotics

A different group of therapeutic agents for therapy of IBD are probiotics. The use of probiotics has been advocated in colonic inflammatory disease for a long time. Only recently, two controlled trials demonstrated that E. coli nissle is as effective as 5-ASA for remission maintenance in ulcerative colitis[83,84]. For remission maintenance and pouchitis, studies demonstrated the benefit of probiotics[85,86]. Due to a better understanding of the molecular events and the pathophysiological processes of this disease, it is hoped that more probiotic agents will be developed in the near future.

5-ASA

A short, practical guideline would be incomplete without discussing IBD and pregnancy. 5-ASA is not harmful during pregnancy and there is very little placental transport. 5-ASA should be avoided during breast feeding because there are no studies on 5-ASA use during breast feeding[87]. Acute disease or a flare up of IBD can be treated throughout an entire pregnancy with steroids. Glucocorticoids pass the placental barrier, but there has been no significant evidence of teratogenesis. There have been some observations of cleft lip and palate associated with the intake of steroids. In general, no increase in fetal complications have been found with use of 5-ASA compared to the general population[88].

Azathioprine or 6-mercaptupurine

The use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptupurine should not be completed during pregnancy. Extensive experience with use of these substances during pregnancy exists with other autoimmune diseases and patients who received renal transplants. No teratogenic effects in humans have been reported so far. However, it is very important to discuss all the data and possible complications with the patient and it is essential that the decision to take the drug should be made by the patient[89].

Methotrexate is contraindicated during pregnancy as it is mutagenic and teratogenic[90]. Cyclosporine is not teratogenic, but due to its side-effects, it needs to be considered very carefully and should only be used to avoid a colectomy[91]. Infliximab should not be given as maintenance therapy during pregnancy. In very severe disease, it can be considered as an emergency therapy[92].Nutrition has not been discussed in this article so far. However, the balance of trace elements and vitamins is essential for successful therapy. Vitamin B12 and folinic acid, for example, should be monitored in Crohn’s disease patients with ileal inflammation to avoid a deficiency syndrome, which can lead to severe anemia. Also ferritin should be monitored and, if necessary, substituted orally or intravenously to avoid severe iron deficiency anemia. In severe cases of iron deficiency anemia, erythropoietin (10 000IE s.c. 3 times per week) plus iron i.v. (62.5 mg in 250 mL NaCl) is effective[93]. In severe ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, patients profit from short term parenteral or additional high calorie nutrition[94].

All above treatment regimens attempt to avoid complications and inflammation in IBD. However, all conservative therapy sometimes fails or is not effective enough. Examples might be therapy for refractory ulcerative colitis, which can only be successfully treated by an operation (e.g. a colectomy with an ileoanal pouch anastomosis), non-inflammatory stricture in Crohn’s disease or severe fistulizing disease, in which a protective ileostoma can be very useful for supporting conservative treatment. In such cases, close collaboration with an experienced IBD surgeon is essential.

It can be summarized that although a number of new biological agents have been developed in the last decades for the treatment of IBD, there is still a great need for new pharmcotherapeutics, particularly for chronic refractory disease patients with multiple complications.

Footnotes

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Che YB

References

- 1.Hanauer SB, Meyers S. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:559–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stange EF, Schreiber S, Fölsch UR, von Herbay A, Schölmerich J, Hoffmann J, Zeitz M, Fleig WE, Buhr HJ, Kroesen AJ, et al. [Diagnostics and treatment of Crohn's disease -- results of an evidence-based consensus conference of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases] Z Gastroenterol. 2003;41:19–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-36661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann JC, Zeitz M, Bischoff SC, Brambs HJ, Bruch HP, Buhr HJ, Dignass A, Fischer I, Fleig W, Fölsch UR, et al. [Diagnosis and therapy of ulcerative colitis: results of an evidence based consensus conference by the German society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases and the competence network on inflammatory bowel disease] Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:979–983. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutgeerts PJ. Conventional treatment of Crohn's disease: objectives and outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7 Suppl 1:S2–S8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.3780070503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kühbacher T, Schreiber S, Fölsch UR. Ulcerative colitis: conservative management and long-term effects. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389:350–353. doi: 10.1007/s00423-004-0477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feagan BG. Maintenance therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:S6–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjgastroenterol.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanauer SB, Present DH. The state of the art in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2003;3:81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammà C, Giunta M, Rosselli M, Cottone M. Mesalamine in the maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis adjusted for confounding variables. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1465–1473. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutherland L, Roth D, Beck P, May G, Makiyama K. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for inducing remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000543. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thukral C, Travassos WJ, Peppercorn MA. The Role of Antibiotics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8:223–228. doi: 10.1007/s11938-005-0014-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT, Becktel JM, Best WR, Kern F, Singleton JW. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:847–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malchow H, Ewe K, Brandes JW, Goebell H, Ehms H, Sommer H, Jesdinsky H. European Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:249–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041–1048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modigliani R, Mary JY, Simon JF, Cortot A, Soule JC, Gendre JP, Rene E. Clinical, biological, and endoscopic picture of attacks of Crohn's disease. Evolution on prednisolone. Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:811–818. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90002-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shepherd HA, Barr GD, Jewell DP. Use of an intravenous steroid regimen in the treatment of acute Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:154–159. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith RC, Rhodes J, Heatley RV, Hughes LE, Crosby DL, Rees BI, Jones H, Evans KT, Lawrie BW. Low dose steroids and clinical relapse in Crohn's disease: a controlled trial. Gut. 1978;19:606–610. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.7.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson A, Campieri M, Doe W, Persson T, Nygård G. Oral budesonide as maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease--results of a 12-month study. Global Budesonide Study Group. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:175–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomsen OO, Cortot A, Jewell D, Wright JP, Winter T, Veloso FT, Vatn M, Persson T, Pettersson E. A comparison of budesonide and mesalamine for active Crohn's disease. International Budesonide-Mesalamine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:370–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808063390603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellers G, Cortot A, Jewell D, Leijonmarck CE, Löfberg R, Malchow H, Nilsson LG, Pallone F, Pena S, Persson T, et al. Oral budesonide for prevention of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn's disease. The IOIBD Budesonide Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:294–300. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löfberg R, Rutgeerts P, Malchow H, Lamers C, Danielsson A, Olaison G, Jewell D, Ostergaard Thomsen O, Lorenz-Meyer H, Goebell H, et al. Budesonide prolongs time to relapse in ileal and ileocaecal Crohn's disease. A placebo controlled one year study. Gut. 1996;39:82–86. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukert BP, Raisz LG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathogenesis and management. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:352–364. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-5-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chun A, Chadi RM, Korelitz BI, Colonna T, Felder JB, Jackson MH, Morgenstern EH, Rubin SD, Sacknoff AG, Gleim GM. Intravenous corticotrophin vs. hydrocortisone in the treatment of hospitalized patients with Crohn's disease: a randomized double-blind study and follow-up. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:177–181. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Frequency of glucocorticoid resistance and dependency in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1994;35:360–362. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Candy S, Wright J, Gerber M, Adams G, Gerig M, Goodman R. A controlled double blind study of azathioprine in the management of Crohn's disease. Gut. 1995;37:674–678. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawthorne AB, Logan RF, Hawkey CJ, Foster PN, Axon AT, Swarbrick ET, Scott BB, Lennard-Jones JE. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine withdrawal in ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 1992;305:20–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6844.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:132–142. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-2-199507150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson DC, May GR, Fick G, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine for maintaining remission of Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandborn W, Sutherland L, Pearson D, May G, Modigliani R, Prantera C. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for inducing remission of Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000545. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanauer SB, Korelitz BI, Rutgeerts P, Peppercorn MA, Thisted RA, Cohen RD, Present DH. Postoperative maintenance of Crohn's disease remission with 6-mercaptopurine, mesalamine, or placebo: a 2-year trial. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:723–729. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korelitz BI, Adler DJ, Mendelsohn RA, Sacknoff AL. Long-term experience with 6-mercaptopurine in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1198–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandborn WJ. A review of immune modifier therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:423–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Gelfand MD, Botoman VA, Ball TJ, Wilske KR. Methotrexate induces clinical and histologic remission in patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:353–356. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild G, Sutherland L, Steinhart AH, Greenberg GR, Koval J, Wong CJ, Hopkins M, et al. A comparison of methotrexate with placebo for the maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. North American Crohn's Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1627–1632. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006013422202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Assche G, D'Haens G, Noman M, Vermeire S, Hiele M, Asnong K, Arts J, D'Hoore A, Penninckx F, Rutgeerts P. Randomized, double-blind comparison of 4 mg/kg versus 2 mg/kg intravenous cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egan LJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ. Clinical outcome following treatment of refractory inflammatory and fistulizing Crohn's disease with intravenous cyclosporine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:442–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, Tremaine W. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:940–987. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fellermann K, Ludwig D, Stahl M, David-Walek T, Stange EF. Steroid-unresponsive acute attacks of inflammatory bowel disease: immunomodulation by tacrolimus (FK506) Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1860–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.539_g.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandborn WJ, Present DH, Isaacs KL, Wolf DC, Greenberg E, Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Mayer L, Johnson T, Galanko J, et al. Tacrolimus for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:380–388. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Deventer SJ. Review article: targeting TNF alpha as a key cytokine in the inflammatory processes of Crohn's disease--the mechanisms of action of infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13 Suppl 4:3–8; discussion 38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Medical treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:443–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutgeerts PJ. An historical overview of the treatment of Crohn's disease: why do we need biological therapies? Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4 Suppl 3:S3–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Rutgeerts PJ. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanauer SB. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn's disease: overview of randomized clinical studies. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4 Suppl 3:S18–S24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandborn WJ. New concepts in anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2005;5:10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Travassos WJ, Cheifetz AS. Infliximab: Use in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s11938-005-0011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, et al. Comparison of scheduled and episodic treatment strategies of infliximab in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:402–413. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rutgeerts P, D'Haens G, Targan S, Vasiliauskas E, Hanauer SB, Present DH, Mayer L, Van Hogezand RA, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) to maintain remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:761–769. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Present D, Sands BE, Sandborn W, Olson A. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial Of Infliximab Therapy for Active Ulcerative Colitis. :the Act 1 Trial. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandborn WJ, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Olson A, Joharms J, Traverse S, Colombel JF. Infliximab Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. :the Act 2 Trial. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schreiber S, Campieri M, Colombel JF, van Deventer SJ, Feagan B, Fedorak R, Forbes A, Gassull M, Gendre JP, van Hogezand RA, et al. Use of anti-tumour necrosis factor agents in inflammatory bowel disease. European guidelines for 2001-2003. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:1–11; discussion 12-13. doi: 10.1007/s003840100285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanauer SB, Wagner CL, Bala M, Mayer L, Travers S, Diamond RH, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P. Incidence and importance of antibody responses to infliximab after maintenance or episodic treatment in Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:542–553. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, D' Haens G, Carbonez A, Rutgeerts P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601–608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Farrell RJ, Alsahli M, Jeen YT, Falchuk KR, Peppercorn MA, Michetti P. Intravenous hydrocortisone premedication reduces antibodies to infliximab in Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:917–924. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheifetz A, Smedley M, Martin S, Reiter M, Leone G, Mayer L, Plevy S. The incidence and management of infusion reactions to infliximab: a large center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1315–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanauer S, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, D'Haens G, Targan S, Kam L, Present D, Mayer L, Wagner C, LaSorda J, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity to infliximab (Remicade) reinfusion after a 2-4 year interval without treatment. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:A731. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Remicade [package insert] Malvern. PA: Centocor; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vermeire S, Noman M, Van Assche G, Baert F, Van Steen K, Esters N, Joossens S, Bossuyt X, Rutgeerts P. Autoimmunity associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment in Crohn's disease: a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:32–39. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00701-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohan N, Edwards ET, Cupps TR, Oliverio PJ, Sandberg G, Crayton H, Richert JR, Siegel JN. Demyelination occurring during anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy for inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2862–2869. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2862::aid-art474>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas CW, Weinshenker BG, Sandborn WJ. Demyelination during anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy with infliximab for Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:28–31. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown SL, Greene MH, Gershon SK, Edwards ET, Braun MM. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: twenty-six cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3151–3158. doi: 10.1002/art.10679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kwon HJ, Coté TR, Cuffe MS, Kramer JM, Braun MM. Case reports of heart failure after therapy with a tumor necrosis factor antagonist. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:807–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, Mirabile-Levens E, Kasznica J, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee JH, Slifman NR, Gershon SK, Edwards ET, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Wise RP, Brown SL, Udall JN, Braun MM. Life-threatening histoplasmosis complicating immunotherapy with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists infliximab and etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2565–2570. doi: 10.1002/art.10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Velayos FS, Sandborn WJ. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia during maintenance anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy with infliximab for Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:657–660. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200409000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Papadakis KA, Shaye OA, Vasiliauskas EA, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky MC, Birt J, Paavola J, Lee SK, Price J, Targan SR, et al. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab (D2E7) in Crohn's disease patients with an attenuated response to infliximab. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:75–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer S, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Kane S, Cohen R, Hanson K, Johnson T, Schmitt D, Jeche R. An open-label study of the human anti-TNF monoclonal antibody adalimumab in subjects with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab for Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1984–1989. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Youdim A, Vasiliauskas EA, Targan SR, Papadakis KA, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky MC, Lechago J, Paavola J, Loane J, Lee SK, et al. A pilot study of adalimumab in infliximab-allergic patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:333–338. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baker DE. Adalimumab: human recombinant immunoglobulin g1 anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2004;4:196–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schreiber S, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Kamm MA, Boivin M, Bernstein CN, Staun M, Thomsen OØ, Innes A. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of certolizumab pegol (CDP870) for treatment of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:807–818. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Radford-Smith G, Kovacs A, Enns R, Innes A, Patel J. CDP571, a humanised monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor alpha, for moderate to severe Crohn's disease: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1485–1493. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Katz S, Safdi M, Wolf DG, Baerg RD, Tremaine WJ, Johnson T, Diehl NN, Zinsmeister AR. Etanercept for active Crohn's disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1088–1094. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.D'Haens G, Swijsen C, Noman M, Lemmens L, Ceuppens J, Agbahiwe H, Geboes K, Rutgeerts P. Etanercept in the treatment of active refractory Crohn's disease: a single-center pilot trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2564–2568. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rutgeerts P, Lemmens L, Van Assche G, Noman M, Borghini-Fuhrer I, Goedkoop R. Treatment of active Crohn's disease with onercept (recombinant human soluble p55 tumour necrosis factor receptor): results of a randomized, open-label, pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:185–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Enns R, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lawrance IC, Panaccione R, Sanders M, Schreiber S, Targan S, et al. Natalizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1912–1925. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, Dubois B, Vermeire S, Noman M, Verbeeck J, Geboes K, Robberecht W, Rutgeerts P. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:369–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schreiber S, Nikolaus S, Malchow H, Kruis W, Lochs H, Raedler A, Hahn EG, Krummenerl T, Steinmann G. Absence of efficacy of subcutaneous antisense ICAM-1 treatment of chronic active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1339–1346. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mannon PJ, Fuss IJ, Mayer L, Elson CO, Sandborn WJ, Present D, Dolin B, Goodman N, Groden C, Hornung RL, et al. Anti-interleukin-12 antibody for active Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2069–2079. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nikolaus S, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak R, Steinhart AH, Wild GE, Theuer D, Möhrle J, Schreiber S. Interferon beta-1a in ulcerative colitis: a placebo controlled, randomised, dose escalating study. Gut. 2003;52:1286–1290. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:635–639. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kruis W, Schütz E, Fric P, Fixa B, Judmaier G, Stolte M. Double-blind comparison of an oral Escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:853–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Venturi A, Lammers KM, Brigidi P, Vitali B, Poggioli G, Miglioli M, Campieri M. Prophylaxis of pouchitis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1202–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mimura T, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Poggioli G, Schreiber S, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Gionchetti P, Campieri M, Kamm MA. Once daily high dose probiotic therapy (VSL#3) for maintaining remission in recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Gut. 2004;53:108–114. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Diav-Citrin O, Park YH, Veerasuntharam G, Polachek H, Bologa M, Pastuszak A, Koren G. The safety of mesalamine in human pregnancy: a prospective controlled cohort study. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mogadam M, Dobbins WO, Korelitz BI, Ahmed SW. Pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease: effect of sulfasalazine and corticosteroids on fetal outcome. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alstead EM, Ritchie JK, Lennard-Jones JE, Farthing MJ, Clark ML. Safety of azathioprine in pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:443–446. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Donnenfeld AE, Pastuszak A, Noah JS, Schick B, Rose NC, Koren G. Methotrexate exposure prior to and during pregnancy. Teratology. 1994;49:79–81. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420490202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Radomski JS, Ahlswede BA, Jarrell BE, Mannion J, Cater J, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT. Outcomes of 500 pregnancies in 335 female kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:1089–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aberra FN. To be or not to be: infliximab during pregnancy? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:76–78. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000186489.53493.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schreiber S, Howaldt S, Schnoor M, Nikolaus S, Bauditz J, Gasché C, Lochs H, Raedler A. Recombinant erythropoietin for the treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:619–623. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603073341002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.O'Sullivan M, O'Morain C. Nutritional Treatments in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:207–213. doi: 10.1007/s11938-001-0033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]