Abstract

Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung are very uncommon and occur usually in patients with terminal stage disease. These metastases are usually asymptomatic, but may present as perforation, obstruction, malabsorption, or hemorrhage. Hemorrhage as a first presentation of small bowel metastases is extremely rare and is related to very poor patient survival. We describe a case of a 61- year old patient with primary adenocarcinoma of the lung, presenting with melena as the first manifestation of small bowel metastasis. Both primary tumor and metastatic lesions were diagnosed almost simultaneously. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy performed with a colonoscope revealed active bleeding from a metastatic tumor involving the duodenum and the proximal jejunum. Histological examination and immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen strongly supported the diagnosis of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma, suggesting that small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung occur usually in patients with terminal disease and rarely produce symptoms. Gastrointestinal bleeding from metastatic small intestinal lesions should be included in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal blood loss in a patient with a known bronchogenic tumor.

Keywords: Melena, Duodenal metastases, Lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Metastases affecting the small bowel and originating from carcinoma of the lung are rare, but recent reports suggest that they may be more frequent than previously thought as they rarely produce symptoms[1-3].

The majority of patients with metastases of the small bowel reported in the literature, present with bowel perforation[2-4]. Overt gastrointestinal hemorrhage has been described in a few cases as a prelude to bowel perforation, whilst it has been described only rarely as the main presentation[5-7].

We present a case of a 61-year old patient with upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to small bowel metastases from a primary adenocarcinoma of the lung with secondary deposits in the abdominal lymph nodes. Metastatic involvement of the duodenum presenting with melena has been described rarely in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 61-year old man was admitted to our hospital with a two-day history of melena. He reported a four-month history of weakness, anorexia, 5 kg loss of weight, cough, dyspnea on exertion, and blood-stained sputum, and a two-month history of fatigue and altered bowel habits. He was a cigarette smoker with chronic obstructive airway disease and arterial hypertension.

On examination he was pale, with normal blood pressure and pulse rate. He had wheezy breathing and decreased breath sounds in the upper right lung region. Melena was proved by digital examination.

Hematocrit was 35% and hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL. Chest x-ray demonstrated a density in the upper region of the right lower lobe. Endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract up to the second part of the duodenum revealed erosive antral gastritis, but no active bleeding site. CT scan of the thorax disclosed an irregularly-shaped nodular mass measuring 4 cm in diameter, in the upper region of the right lower lobe of the lung. Bronchial biopsy revealed the presence of blood clots and desquamated bronchial epithelial cells, without signs of malignancy. The results of cytological examination of bronchial excretions, however, proved positive for non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. Staging of the disease followed by CT scan of the upper and lower abdomen and the retroperitoneal space showed multiple, enlarged bilateral para-aortic, and mesenteric lymph nodes.

The patient was started on combined chemotherapy with cisplatin and hydrochloric gemsitabine. His bowel motions became normal by the third day of hospitalization and he was subsequently discharged, denying further investigation.

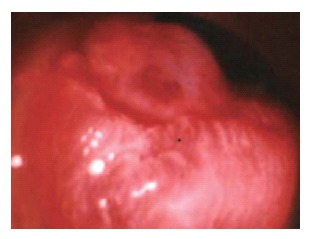

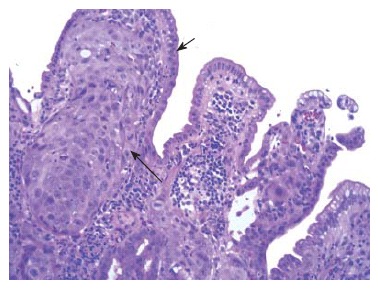

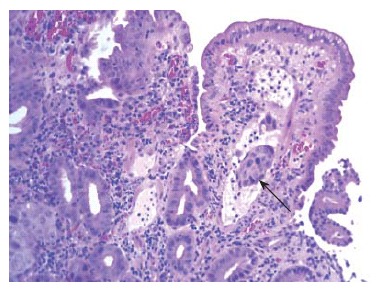

During admission for the second round of chemo-therapy and one month after diagnosis, the patient complained of diffuse abdominal pain and tenderness. Shortly afterwards this was accompanied with hemodynamic instability and tachypnea. Melena was proved by digital examination. Hematocrit fell from 34% to 26%, hemoglobin from 9 g/dL to 6 g/dL, and serum urea/creatinine ratio was greater than 40 (urea being 60mg/dL and creatinine 1.3 mg/dL). Plain abdominal X-ray showed no abnormalities and the patient underwent endoscopy of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract using a Pentax© 160 cm colonoscope for both examinations. In the 4th part of the duodenum three irregular, nodular protrusions of the mucosa measuring 0.5-1.5 cm in diameter were observed. They were friable and slightly hemorrhagic. At the proximal jejunum there was a larger hemorrhagic polypoid mass about 2.5 cm in diameter (Figure 1). Biopsies of these lesions revealed gatherings of poorly-differentiated neoplastic cells invading the mucosal bed and extending into the intestinal villi with sparing of the superficial epithelium (Figure 2). Infiltration of the lymph vessels was also noted (Figure 3). These findings were consistent with metastatic disease. Immunohistochemical staining for keratins 8, 18, 19 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF 1) as well as histochemical staining for periodic acid schiff (PAS) strongly supported the diagnosis of poorly-differentiated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung. Radiological examination of the small bowel was not completed due to patient discomfort. The patient was transfused with 3 units of packed erythrocytes and 3 units of fresh frozen plasma.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic appearance of a large hemorrhagic polypoid mass at the proximal jejunum, representing metastatic lung carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Gatherings of poorly-differentiated neoplastic cells invading the mucosal bed, and extending into the intestinal villi (long arrow), with sparing of the superficial epithelium (short arrow).

Figure 3.

Embolus of neoplastic cells in lymph vessels of the intestinal villi.

Only four cycles of chemotherapy were carried out due to deterioration of the patient. In addition, he received 4000 U of erythropoietin per week. Three months after his last episode of melena the patient continued to have occult upper gastrointestinal bleeding and was admitted on several occasions for blood transfusion. The patient died seven months after the diagnosis of end stage cancer of the lung.

DISCUSSION

Small bowel metastases usually originate from primary carcinomas of the gastrointestinal or genital organs, and more specifically from the large bowel, uterus, cervix, ovaries, and testes. Thoracic malignancies metastasize less frequently to the small bowel. Apart from carcinoma of the lung, these also include malignant melanoma, carcinoma of the breast, carcinoma of the salivary glands, carcinoma of the esophagus, and rhabdomyosarcoma of the lung[1,8,9].

Our patient had histologically-proven small intestinal lesions originating from primary lung adenocarcinoma. A review of the literature revealed few studies of patients with lung cancer and metastases to the small bowel. An extensive eleven-year study of patients with primary lung cancer revealed that at autopsy, 46 out of 431 patients (10.6%) had secondary deposits in the small bowel[1]. These patients had an average of 4.8 metastatic sites. A more recent study of patients with non-small cell carcinoma of the lung revealed small bowel metastases in 4.6% of cases[9]. It should be emphasized that all these cases had adenocarcinomas, with a disease stage greater than IIIA, as well as a minimum of two other metastatic sites before the development of bowel metastases. Another large study involved 1399 patients with lung cancer who underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor[2]. This study revealed a much smaller percentage (0.5%) of symptomatic patients having small bowel metastases. In direct contrast to the previous study, which concludes that adenocarcinoma is the cell type resulting more frequently in small bowel metastasis, this study concludes that squamous cell carcinoma is the more frequent cause, accounting for 61% of cases.

Patients with primary lung cancer with metastases to the small bowel are usually asymptomatic[10,11]. Less frequently these metastases can cause symptoms which vary according to the way the metastatic tumor invades the bowel wall. Rapid tumor growth leads to symptoms of obstruction, although it seems that perforation occurs more commonly probably due to central tumor necrosis. Most cases of primary lung cancer and small bowel metastasis present with small bowel perforation[3,4,10]. According to a recent study, 98 cases of perforated lung cancer metastasis to the small intestine have been described in the literature since 1960[3]. When ulceration of the mucosa occurs the metastatic tumor may bleed, whilst large extension of tumor may lead to symptoms of malabsorption[1].

Hemorrhage from a metastatic tumor in the small bowel is uncommon, explaining the absence of large studies on this issue. A small number of isolated cases, however, have been described. They describe patients over the age of 55 years, with primary lung carcinoma of large or small cell types, who have already developed distant metastases, and these patients usually present with acute hemorrhage from ulceration of the metastatic tumor, and less frequently with iron deficiency anemia, or with non-specific abdominal symptoms before the onset of melena[12-15]. In one case report, the patient presented with iron-deficiency anemia and melena, and the diagnosis of primary lung cancer was made after surgical resection of the intestinal metastasis, as no tumor evidence was found on chest x-ray[2]. The presence of small bowel metastases in this patient was confirmed by CT scanning, as upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies were negative.

A very small number of cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to duodenal metastases from lung cancer have been reported[5-7,12]. Small intestinal metastases have been reported to occur more frequently in the jejunum and terminal ileum than the duodenum[2,3,16]. As in our case, metastatic lesions of the small bowel from lung carcinoma are usually multiple[1,11].

Our patient is one of the very few cases described where melena as the first manifestation of small bowel metastasis, has arisen from the duodenum and jejunum[5-7,12,16]. Also it is interesting to note that the time interval was short between diagnosis of cancer and metastasis to the small bowel, as the patient presented with melena before the establishment of the diagnosis of lung carcinoma and was still in a good general state of health. The diagnosis of metastatic involvement of the small bowel was suspected, but not confirmed at the beginning. This emphasizes the importance of considering the presence of small bowel metastases in a patient with lung cancer displaying symptoms of hemodynamic instability, melena, or abdominal symptoms such as dyspepsia, distention and pain, even if the time elapsed from the time of diagnosis of cancer is short. It should be noted that occult gastrointestinal bleeding must be suspected if laboratory investigations reveal iron deficiency anemia, or a fall in hematocrit or hemoglobin, even in an asymptomatic patient.

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage can usually be managed conservatively with intravenous fluids and red blood cell transfusion until the patient is hemodynamically stable and hemorrhage ceases. However, cases requiring surgical resection of small bowel in order to control massive hemorrhage have also been reported[12,16]. Only a few patients have survived more than 9 mo after surgical resection of intestinal metastases, with the exception of one patient who survived 22 mo after peritonitis [2]. Perioperative mortality has decreased considerably, and the question of whether surgery should be considered as palliative therapy not only for symptomatic patients remains to be solved. After hemorrhage from small bowel metastases, patient survival varies between several weeks to several months[6,13]. It seems that hemorrhage originating from small bowel metastases, is related to a very poor patient survival. The patient we presented, survived for a considerably long time (7 mo after his first episode of bleeding). During this period of time he continued to have microscopic bleeding requiring occasional blood transfusion. Active gastrointestinal bleeding from small bowel metastases has never been described as the cause of death in patients suffering from carcinoma of the lung.

In conclusion, small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung occur usually in patients with terminal disease and rarely produce symptoms. Hemorrhage as a first presentation of small bowel metastases is extremely rare, especially when these are located in the duodenum, with a poor prognosis. Gastrointestinal bleeding from metastatic small intestinal lesions should be included in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal blood loss in a patient with a known bronchogenic tumor.

Footnotes

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.McNeill PM, Wagman LD, Neifeld JP. Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1987;59:1486–1489. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870415)59:8<1486::aid-cncr2820590815>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger A, Cellier C, Daniel C, Kron C, Riquet M, Barbier JP, Cugnenc PH, Landi B. Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung: clinical findings and outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1884–1887. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garwood RA, Sawyer MD, Ledesma EJ, Foley E, Claridge JA. A case and review of bowel perforation secondary to metastatic lung cancer. Am Surg. 2005;71:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savanis G, Simatos G, Lekka I, Ammari S, Tsikkinis C, Mylonas A, Kafasis E, Nissiotis A. Abdominal metastases from lung cancer resulting in small bowel perforation: report of three cases. Tumori. 2006;92:185–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinhart AH, Cohen LB, Hegele R, Saibil FG. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to superior mesenteric artery to duodenum fistula: rare complication of metastatic lung carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:771–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinoshita E, Nakahashi H, Wakasugi K, Kaneko S, Hamatake M, Sugimachi K. Duodenal metastasis from large cell carcinoma of the lung: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:799–802. doi: 10.1007/BF02482332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamiyoshihara M, Otaki A, Nameki T, Kawashima O, Otani Y, Morishita Y. Duodenal metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma of the lung; report of a case. Kyobu Geka. 2004;57:151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenbygaard LE, Sørensen JB. Small bowel metastases in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 1999;26:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(99)00075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ise N, Kotanagi H, Morii M, Yasui O, Ito M, Koyama K, Sageshima M. Small bowel perforation caused by metastasis from an extra-abdominal malignancy: report of three cases. Surg Today. 2001;31:358–362. doi: 10.1007/s005950170161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillenbrand A, Sträter J, Henne-Bruns D. Frequency, symptoms and outcome of intestinal metastases of bronchopulmonary cancer. Case report and review of the literature. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2005;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomas D, Ledinsky M, Belicza M, Kruslin B. Multiple metastases to the small bowel from large cell bronchial carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1399–1402. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cremon C, Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Salvioli B, Epifanio G, Gizzi G, Stanghellini V, Corinaldesi R. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to duodenal metastasis from primary lung carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:141–143. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanemoto K, Kurishima K, Ishikawa H, Shiotani S, Satoh H, Ohtsuka M. Small intestinal metastasis from small cell lung cancer. Intern Med. 2006;45:967–970. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanli Y, Adalet I, Turkmen C, Kapran Y, Tamam M, Cantez S. Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung: presenting with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ann Nucl Med. 2005;19:161–163. doi: 10.1007/BF03027397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locher C, Grivaux M, Locher C, Jeandel R, Blanchon F. Intestinal metastases from lung cancer. Rev Mal Respir. 2006;23:273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0761-8425(06)71578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akahoshi K, Chijiiwa Y, Hirota I, Ohogushi O, Motomatsu T, Nawata H, Sasaki I. Metastatic large-cell lung carcinoma presenting as gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1996;59:217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]