Abstract

The present study examined the structural validity of the 25-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a large sample of U.S. veterans with military service since 9/11/2001. Participants (n=1981) completed the 25-item CD-RISC, a structured clinical interview and a self-report questionnaire assessing psychiatric symptoms. The study sample was randomly divided into two sub-samples, an initial sample [Sample 1: n = 990] and a replication sample [Sample 2: n = 991]. Findings derived from exploratory factor analysis (EFA) did not support the five-factor analytic structure as initially suggested in Connor and Davidson’s (2003) instrument validation study. Although Parallel Analyses (PA) indicated a two-factor structural model, we tested one to six factor solutions for best model fit using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Results supported a two-factor model of resilience, comprised of adaptability (8-item) and self-efficacy (6-item) themed items however, only the adaptability themed factor was found to be consistent with our view of resilience —a factor of protection against the development of psychopathology following trauma exposure. The adaptability themed factor may be a useful measure of resilience for post 9/11 U.S. military veterans.

Keywords: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, exploratory factor analysis, psychometric testing, military

Resilience has been defined as the ability to adapt successfully in the face of adversity, and thus, can serve as a protective factor following exposure to stress and trauma (Bonnano, 2004; Richardson, 2002). Resilience is thought to be a dynamic process and a multidimensional construct with biological, psychological, and spiritual factors that influence the ability to cope with stress (Richardson, 2002). When encountering internal and external demands, humans can develop and utilize adaptations and protective factors to decrease the potential for long-term psychological disruption and to grow and adapt to future stressors (Richardson, 2002; Richardson, Neiger, Jensen, & Kumpfer, 1990).When such adaptations do not occur, maladaptive strategies may be used to cope with stressors, potentially leading to further disruption and stress (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Richardson, 2002). Individuals with higher resilience may experience some form of transitory stress following a traumatic event, yet these reactions are less likely to significantly impair functioning (Bonnano & Mancini, 2012).

Understanding the role of resilience in trauma-exposed populations, especially a military population, can inform prevention and treatment efforts aimed to strengthen coping abilities and decrease the potential negative impact of trauma, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, depression, and poor psychosocial adjustment (Pietrzak, et al., 2010; Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011). PTSD, depression, generalized anxiety, and other mental health concerns are prevalent within post 9/11 U.S military veterans (Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007). Several studies have reported that 10 - 19% of veterans meet the screening criteria for these disorders following deployment (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Hoge, et al., 2004). The protective effect of resilience on negative psychological functioning has been documented in studies of post 9/11 U.S. military veterans (Green, Calhoun, Dennis, Workgroup, & Beckham, 2010; Mansfield, Bender, Hourani, & Larson, 2011; Pietrzak, et al., 2010; Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011). The need to assess resilience in the context of evaluating both risk and protective factors calls for a valid and reliable measure of resilience within military and veteran populations.

Connor and Davidson (2003) developed the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) to measure resilience within adult populations. Based on work examining hardiness, protective factors against psychopathology, and traits associated with adaptive responses to stress (e.g., Kobasa, 1979; Lyons, 1991; Rutter, 1985), they generated items thought to tap self-efficacy, sense of humor, secure attachment to others, the ability to adapt to change, commitment, control, thinking of change as a challenge, patience, the ability to tolerate stress and pain, optimism and faith (Connor & Davidson, 2003). The final CD-RISC consists of 25 internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha = .89) items, each rated on a 5-point scale (0 ‘not true at all’ to 4 ‘true nearly all of the time’), yielding a total score which can range from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting a higher level of resilience. Five factors were generated using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) during the initial validation study can be computed. The five factors were based on EFA in a sample of community dwelling adults (n = 577) and were selected based on eigenvalues greater than 1.00 (Connor & Davidson, 2003). These subscales or factors included: “personal competence, high standards, and tenacity” (factor 1), “trust in one’s instincts, tolerance of negative affect, and strengthening effects of stress” (factor 2), “positive acceptance of change and secure relationships” (factor 3), “control” (factor 4), and “spiritual influences” (factor 5; Connor & Davidson, 2003).

Studies attempting to replicate the factor structure of the CD-RISC have generally not supported the five-factor structure. Among populations of various ages, ethnicities, and trauma exposures, the CD-RISC has yielded varying factor structures. Accordingly, concerns have been raised regarding the difficulty in establishing clear dimensions for this measure as well as the nature of the resilience construct. It has been largely accepted that the construct of resilience is multidimensional (c.f., Burns & Anstey, 2010); however, the CD-RISC has failed to support this in a consistent, meaningful way. While some research has supported a three-factor solution (Karairmek, 2010; Yu & Zhang, 2007), other research has yielded a four-factor solution (Bitsika, Sharpley, & Peters, 2010; Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007; Khoshoeui, 2009; Singh & Yu, 2010; Lamond et al., 2008). A number of other reports have obtained a five-factor structure, although not always identical in content (Baek, Lee, Joo, Lee, & Choi, 2010; Catalano, Hawkins, & Toumbourou, 2008; Gillespie, Chaboyer, Wallis, & Grimbeek, 2007; Ito, Nakajima, Shirai, & Kim, 2009; Pietrzak et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011). Finally, at least two studies have yielded ambiguous factor structures (two or three factors, Jorgensen & Seedat, 2008; four or five factors, Sexton, Byrd, & von Kluge, 2010). Researchers have described a lack of “a sufficient number of items” as a cause for the inconsistency observed in the CD-RISC factor structure. For example, factor 5 (spiritual influences) of the CD-RISC is supported by only two items while the “control” themed subscale contains 3 items. Conventional guidance dictates that three or more strongly loaded items are necessary for ensuring factor reliability.

In one of the largest validation studies of the CD-RISC, Campbell-Sills and Stein (2007) evaluated the psychometric characteristics of the 25-item measure in a sample of 1,743 undergraduate students. Using two independent samples and a combination of EFA and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), they eliminated items that did not load consistently or had unrelated item content with other items on a particular factor. This process yielded a shorter (10-item) unifactorial measure of resilience. To date, this single-factor measure of resilience has been validated amongst diverse populations, including Chinese adult earthquake victims (Wang, Shi, Zhang, & Zhang, 2010) and adolescent and adult Australian cricketers (Gucciardi, Jackson, Coulter, & Mallett, 2011). In contrast, a study by Burns and Anstey (2010) derived a one-dimensional 22-item scale from the complete 25-item CD-RISC, finding it comparable to both the original 25- and revised 10-item scales. Given the variability across studies in support of both a unidimensional and multidimensional factor solutions to the CD-RISC, we do not recommend use of the CD-RISC factors as stand-alone subscales.

Absent a universally accepted theory for resilience and research indicating both a unitary and multi-factorial structure for the CD-RISC scale, the dimensionality of resilience among post 9/11 U.S. military veterans is unclear. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to examine the factor structure of the 25-item CD-RISC in a trauma-exposed veteran sample. Although studies within this military population have used the 25-item CD-RISC (Green, Calhoun, Dennis, Workgroup, & Beckham, 2010; Mansfield, Bender, Hourani, & Larson, 2011; Pietrzak, et al., 2010; Pietrzak & Southwick, 2011), to our knowledge, no published study has directly examined the factor structure of the CD-RISC in a post 9/11 U.S veteran sample. A secondary aim was to evaluate the concurrent validity of the CD-RISC as a potential protective factor against psychiatric symptoms following trauma exposure.

Methodology

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected from research volunteers enrolled in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) multi-site study of post 9/11 U.S military veterans. Participant eligibility criteria included: 1) military service on or after September 11, 2001, 2) English speaking; and 3) a reading comprehension level at the 8th grade. Study recruitment involved the use of fliers, referrals by VA clinics, and invitational letters mailed to VA enrollees describing a study on post-deployment related health issues. Subjects received up to $175 for study participation. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all participating VA medical centers (VAMC) located in North Carolina (Durham VAMC, W. G. (Bill) Hefner VAMC) and Virginia (Hampton VAMC, Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC). After a complete description of the study, written informed consent was acquired. Study participants (N=1981) included in the current analysis were consented between June 2005 and October 2011. Seventy-eight percent (78%) of participants endorsed serving in the region of conflict during Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). Moreover, 35% of participants endorsed using VA healthcare services.

Demographic Information

Demographic data collected as part of this study included age, gender, race, marital status, education level, working status, and military service status.

Resilience

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) is a reliable, self-report measure used for evaluating resilience (Connor & Davidson, 2003). The reliability estimate for the 25-item CD-RISC in the current study population was α = .96.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) was used to establish psychiatric diagnoses for PTSD and major depressive disorder (MDD). The SCID-I/P is a semi-structured diagnostic interview for determining DSM-IV-TR Axis I diagnoses (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1994). Study interviewers (n=22) completed an extensive program of training involving the rating of 7 video recorded interviews and received instruction from experienced interviewers. Moreover, interviewers participated in bi-weekly reliability meetings and were supervised by licensed clinical psychologists. Strength of agreement for Axis I diagnoses among the study interviewers was excellent, as evidenced by an inter-rater concordance (Fleiss’ kappa) value of .96 (Fleiss, Levin, & Cho Paik, 2003; Nunnally, Bernstein, & 1994).

Psychological Symptoms

The Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) is a 90-item self-report instrument designed to evaluate a broad range of psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Participants rate each item on a five-point Likert-type scale of distress, ranging from “0 = not at all” to “4 = extremely.” The SCL-90R is comprised of nine key psychiatric symptom categories namely, somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Additionally, the SCL-90R is comprised of three global indices, the General Symptom Index (GSI) which provides a measure of overall psychological distress, Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI) for assessing symptom intensity, and the Positive Symptom Total (PST) for measuring the number of reported symptoms (Kinney & Gatchel, 1991). Cronbach’s α for the SCL-90-R GSI index in the current study was estimated at .99.

Combat Exposure

The Combat Exposure Scale (CES) is a 7-item self-report measure that assesses experiences and/or situations generally observed in war. CES items are rated on a 5-point frequency scale (ranging from 0-4) and are computed using a sum of weighted scores. Moreover, total CES scores are categorized based upon level of combat exposure (ranging from “light” to “heavy”; Keane et al., 1989).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the demographics and clinical characteristics were calculated including the mean, standard deviations, counts, and frequencies for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

EFA was used to test the factorial structure of the 25-item version of the CD-RISC. The study sample (n=1981) was randomly divided into two sub-samples: an initial sample [Sample 1: n = 990] and a replication sample [Sample 2: n = 991]. Independent EFAs were conducted on each sample and results were evaluated to determine the stability of the factorial structure across both samples. Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) rather than Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) was performed because of the significant negative skew of each of the individual items of the CD-RISC (mean skew = −0.80, all ps < .01) (for a discussion of both methods, see Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum, & Strahan, 1999). Promax rotation was selected based on the assumption that the CD-RISC factors were correlated. Parallel analysis (PA; Horn, 1965) was used to determine the number of factors to retain. Evidence has shown PA to be a more reliable method for determining the number of significant factors to extract compared to conventional statistical indices such as the Kaiser eigenvalue greater than 1 criterion (Kaiser, 1960) or Cattell’s scree test (Cattell, 1966) (Fabrigar et al., 1999; Hayton et al., 2004; Hoyle & Duvall, 2004). Kabacoff’s (1995) SAS macro involving the 95th percentile estimate for significant loadings was used for PA (Horn, 1965). Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2001) criterion for minimum loading, .32, was used to identify loading and cross-loading items. EFA were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 while (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Model fit was determined using standardized indices such as root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <.08, and comparative fit index (CFI) >.90.

Following EFA, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to compare the model specified by EFA to Connor and Davidson’s original five-factor solution. Finally, latent variable analysis was undertaken to determine the concurrent association between the various CD-RISC solutions and psychological indicators. CFA was conducted using AMOS, v20 (Arbuckle, 2006).

Results

Sample Description

Sample characteristics for the 1981 participants are presented in Table 1. Participants reported a mean age of 37years (SD = 10; range = 19-68). Forty-nine percent of participants were identified as Black or African American. Furthermore, the study sample was largely male (80%), and the majority of participants were married (60%). Sixty-five percent of the study population was employed and the mean years of education were 13 (SD = 3.4). A little over half of the sample (51%) was discharged from military service, 32% had current military service in the Reserves (i.e. National Guard and/or Reserves), and the remainder was retired (9%) or active duty (6%). A large majority of the study sample (86%) served in a warzone or region of conflict in support of combat operations in the Middle East. Note that in the analyses presented below, the total sample was randomly divided into two sub-samples (Sample 1: n = 990; Sample 2: n = 991). No statistical differences were detected between these groups regarding demographic features.

Table 1. Descriptive and Clinical Characteristics.

| Total Sample | |

|---|---|

| Age [M(SD)] | 37.27(10.05) |

| Gender (n, % Male) | 1586 (80%) |

| Race | |

| n, % Black or African American | 966 (49%) |

| n, % White (including Hispanic) | 921 (46%) |

| n, % Other | 94 (5%) |

| Education [M(SD)] | 13.46 (3.42) |

| Marital Status | |

| n, % Married (including separated) | 1193 (60%) |

| Number of Times Divorced [M(SD)] | 0.52 (0.74) |

| Military Status | |

| n, % Active Duty | 122 (6%) |

| n, % Reserve Forces Dutya | 662 (34%) |

| n, % Discharged | 1197 (60%) |

| Combat Exposure Scale [M(SD)] | 11.73 (10.72) |

| Employment Status (n, % Working) | 1287 (65%) |

| Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, 25-item [M(SD)] | 72.66(18.44) |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Lifetime (n, %) | 683 (39%) |

| SCL 90-R (Global Severity Index) [M(SD)] | 0.93 (0.85) |

Note. N= 1981. SCL-90-R = Symptom Checklist Revised;

Reserve Forces Duty includes study participants serving in the National Guard or Reserves

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) of the 25-item CD-RISC

To determine the factor structure of the CD-RISC, we submitted the 25-item measure to PAF with promax rotation separately for Samples 1 and 2. Although PA from both samples suggested a 2- or 3-factor structure, we examined 1-through 6-factor solutions to determine relative fit via number of items loading on each factor, number of cross-loading and non-loading items, and factor stability across the sub-samples. Solution characteristics for both groups are summarized in Table 2. Across both groups, the 6-, 5-, and 4-factor solutions produced one or more factors defined by just one or two items. The 3-factor solution yielded no factors with two or fewer items. However, only 12 items demonstrated consistent loading across the two groups, suggesting little stability and coherence in the 3-factor solution. The 2- and single-factor solutions yielded far greater consistency in factor loading across the two samples, yet merged seemingly disparate themes into single factors.

Table 2. Exploratory Factor Analyses Solution Summaries.

| Sample 1 (n = 990) | Sample 2 (n = 991) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Solution | 1- or 2-Item Factors |

Cross- loading Items |

Non- loading Items |

Var. Explained |

1- or 2-Item Factors |

Cross- loading Items |

Non- loading Items |

Var. Explained |

Shared loadings |

| 25-Item Version | |||||||||

| 6 Factors | 2 | 3 | 0 | 70.01% | 2 | 2 | 0 | 72.31% | 19 |

| 5 Factors | 1 | 4 | 0 | 67.15% | 2 | 1 | 0 | 69.54% | 19 |

| 4 Factors | 2 | 5 | 1 | 64.03% | 2 | 2 | 1 | 66.16% | 11 |

| 3 Factors | 0 | 8 | 0 | 60.30% | 0 | 3 | 0 | 62.32% | 12 |

| 2 Factors | 0 | 2 | 0 | 56.08% | 0 | 4 | 0 | 58.29% | 19 |

| 1 Factor | N/A | N/A | 3 | 49.93% | N/A | N/A | 4 | 52.36% | 21 |

| 14-Item Version | |||||||||

| 3 Factors | 1 | 2 | 0 | 70.26% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70.08% | 9 |

| 2 Factors | 0 | 1 | 0 | 64.98% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 65.30% | 13 |

| 1 Factor | N/A | N/A | 0 | 58.01% | N/A | N/A | 0 | 58.53% | 14 |

Because we could not confidently identify an optimal model containing all 25 items, we elected to drop items that either formed poorly specified factors (i.e., factors consisting of just one or two items) and/or loaded inconsistently (i.e., failed to load or even cross-load on similar factors across the two samples). Four items (items 2, 3, 9, and 13) fell into the first category. Three of those (items 2, 3, and 9) also failed to load onto either sample’s single-factor solution. Seven additional items (items 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, and 22) loaded inconsistently across the two samples. EFA was repeated on the remaining 14 items. This time, only 3-, 2-, and single-factor models were specified due to removal of items associated with additional factors from the 6-, 5-, and 4-factor solutions (Table 2). PA from both samples suggested a 2-factor solution. Indeed, even with the reduced number of items, the 3-factor solution continued to demonstrate low stability across the two samples, particularly for the third factor, which shared just one item (“I like challenges”) across the two groups. The 2-factor solution demonstrated a high level of correspondence across both groups. The factors were also relatively internally consistent. The first consisted of 8 items (items 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 18, and 19) reflecting adaptability in the face of challenges (e.g, “I am able to adapt when changes occur”). The second factor, consisting of 6 items (items 10, 11, 12, 23, 24, and 25), reflected self-efficacy (e.g., “I take pride in my achievements”). However, at least three of the items from the self-efficacy factor also shared the adaptability theme, namely items 11, 12, and 24. A fourth item (#23) was found to cross-load on both factors in Sample 1. Moreover, both factors were highly correlated across both groups (.79 for Sample 1, .80 for Sample 2).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Given the high level of consistency in the 14-item 2-factor solution across both groups, yet the strong association between the two factors, we next turned to CFA to determine the relative fit of this model as compared to a single-factor solution using data from the full sample. We also tested the fit of the 25-item 5-factor solution. For the CFA, we allowed the factors to covary, although we did not allow items to cross-load.

The 2-factor solution provided an acceptable fit for the overall sample, χ2(76) = 789.81, p < .001; RFI = .95; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .07. All items were highly correlated with their corresponding factors (range: .61 to .82; all ps < .001). However, the intercorrelation between the factors was high (r = .88), suggesting little independence between the latent structures. To determine whether a single-factor model adequately accounted for item variance, we created a nested model in which we set the correlation between the two factors to 1. The single-factor solution provided a significantly worse fit than the 2-factor model, χ2diff(1) = 775.91, p < .001. Thus, we retained the 2-factor structure.

Next we compared our 14-item 2-factor model to the original 25-item 5-factor solution. Because these models contained different items and therefore were not nested, the chi-square test of differences was not appropriate. Instead we referred to the Akaike information criterion (AIC) of each model. The 5-factor solution yielded a considerably higher AIC (3060.29) than the 14-item 2-factor model (875.81), suggesting that the latter provided a better fit.

Reliability and Construct Validity

The entire sample was used to determine how well the 2-factor solution captured the construct of resilience. The 8-item adaptability and 6-item self-efficacy factors were both internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha = .91 and .90, respectively). To demonstrate construct validity, we tested concurrent validity using 16 indices of psychopathology (see Table 3). As expected, levels of psychopathology were high relative to the general population. Furthermore, adaptability and self-efficacy were independently negatively correlated with each index.

Table 3. Psychopathology Means and Correlations with Adaptability and Self-Efficacy.

| Mean (Std. Dev.) | Adaptability | Self-Efficacy | 14-Item Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD, Current | 0.86 (0.92) | −.11* | −.14* | −.13* |

| PTSD, Lifetime | 0.99 (0.94) | −.15** | −.18** | −.17** |

| MDD, Current | 1.39 (0.79) | −.40** | −.36** | −.40** |

| MDD, Lifetime | 1.80 (0.97) | −.38** | −.34** | −.38** |

| Anxiety | 0.86 (0.97) | −.54** | −.49** | −.55** |

| Depression | 1.04 (0.96) | −.61** | −.56** | −.62** |

| Hostility | 0.95 (1.02) | −.49** | −.45** | −.50** |

| Interpersonal | 0.87 (0.95) | −.57** | −.52** | −.57** |

| Obsessive | 1.24 (1.07) | −.57** | −.51** | −.57** |

| Paranoid | 0.98 (0.98) | −.51** | −.43** | −.51** |

| Phobic | 0.69 (0.92) | −.53** | −.48** | −.54** |

| Psychoticism | 0.64 (0.78) | −.53** | −.49** | −.54** |

| Somatization | 0.91 (0.82) | −.47** | −.40** | −.47** |

| GSI | 0.93 (0.85) | −.60** | −.53** | −.60** |

| PST | 40.03 (27.12) | −.61** | −.54** | −.62** |

| PSDI | 1.80 (0.65) | −.45** | −.40** | −.45** |

Note. GSI= Global Severity Index; MDD= Major Depressive Disorder; PST= Positive Symptom Total; PSDI= Positive Symptom Distress Index; PTSD= Posttraumatic Stress Disorder;

p < .05

p < .01.

Given our view that resilience should serve as a protective factor against the development of psychopathology following exposure to traumatic experiences, we tested the moderation of the association between combat exposure and psychopathology by each of the symptom scales. Specifically, we modeled psychopathology as a latent variable based on the 16 aforementioned indices as a function of adaptability, combat exposure, and the interaction between the two. We then substituted adaptability with self-efficacy in a subsequent model.

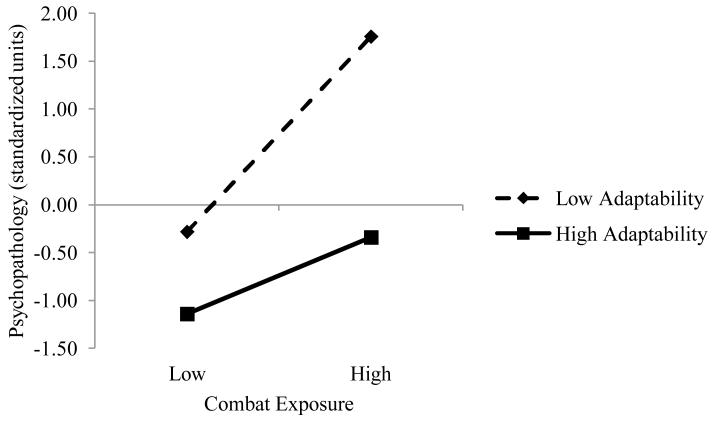

In the first model, adaptability (β = −.74, p = .03) was negatively associated with psychopathology, whereas combat exposure was positively associated with psychopathology (β = .71, p = .03). Both main effects were qualified by a significant interaction (β = −.31, p = .04), which indicated that military veterans exposed to high levels of combat exhibited disproportionately high levels of psychopathology if they scored low on the adaptability scale (see Figure 1). In the second model, self-efficacy was negatively associated with psychopathology (β = −.78, p = .03), whereas combat exposure was positively associated with psychopathology (β = .54, p = .03). The interaction between self-efficacy and combat exposure was not significant (β = −.09, p = .12), suggesting that self-efficacy was not related to the development of psychopathology following exposure to combat.

Figure 1.

Psychopathology level as a function of combat exposure and adaptability. Low values of adaptability and combat exposure reflect scores one standard deviation below the mean of each scale. High values similarly reflect scores one standard deviation above the mean.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the underlying factor structure of the 25-item CD-RISC measure in a post 9/11 U.S veteran population. PA conducted across two subsamples, suggested a two-factor solution for the 25-item CD-RISC in preference to Connor and Davidson’s five-factor pattern. Several factor solutions (1 to 6) were tested for model fit. A two-factor solution comprised of adaptability (8-item) and self-efficacy (6-item) scales emerged as the best fitted model. When tested, the two-factor solution exhibited better internal consistency, a consistent two-factorial structure, and good concurrent validity among both tested samples however, only the adaptability themed scale was found to be consistent with our proposed resilience theory. While the findings of this study bring attention to the complexity in defining the latent characteristics of the resilience construct, results suggest that resilience is unidimensional in a post 9/11 U.S. military population.

Consistent with the majority of other studies examining the factor structure of the CD-RISC, no evidence was found to support a five-factor structure (Jorgensen & Seedat, 2008; Karaimek, 2010; Yu & Zhang, 2007; Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007; Khoshoeui, 2009; Lamond et al., 2008). Interestingly, evidence from other CD-RISC-related studies has suggested a two-factor model. For example, Campbell-Sills and Stein’s (2007) refinement of the 25-item CD-RISC initially supported a two factor solution. However, due to the degree of content overlap between both factors, the authors performed a further refinement of the scale resulting in a uni-dimensional solution. In a sample of South African adolescents, EFA findings generated by Jorgensen and Seedat (2008) revealed the possibility of utilizing either a two or three factor CD-RISC solution. When comparing our results of a two-factor solution to that of previous studies, it is possible that differences in the characteristics of the population under study (e.g., culture, age, trauma exposure) may contribute to some of the observed differences in factor structure. Evidence has shown that resilience factors vary widely across developmental, social, cultural, and environmental contexts. Indeed, more work is needed from both a theoretical and empirical basis to identify factors associated with the resilience construct. As others have noted (McDonald et al., 2008), a measure’s subscales should reflect the underlying factor structure of the construct it is purported to assess. Inconsistencies between a measure’s factor structure and the subscales (i.e., the number of scales is different from the number of factors) will degrade a scale’s factorial validity, bringing into question whether the subscales are valid indicators of the constructs of interest (Clark & Watson, 1995).

While our data indicated a two-factor solution, only the adaptability themed scale was found to be consistent with our concept of resilience--a factor of protection against the development of psychopathology following trauma exposure. The emergence of the adaptability themed factor as important for resilience was not surprising given the characteristics of our study population. Adaptability is an integral component of military culture and training and is heavily emphasized in the tasks and responsibilities often required of military servicemembers. According to Freedman and Burns (2010), “Adaptability requires the capacity to take decisive and effective action in a timely manner, often under pressure.” In the current climate, the military operating tempo requires that troops respond quickly to the ever-changing and extreme conditions of the combat environment. Perhaps, this ability to cope or adapt within these stress-induced conditions serve as a fundamental source of protection against the development of mental illness in this population. From a clinical perspective, these results highlight the significance in understanding the socio-cultural characteristics of the targeted population specifically when identifying potential factors of protection. Like that of the human body and condition, resilience is a complex concept and factors that enhance these processes of protection vary considerably among diverse populations.

When comparing Campbell-Sills and Stein’s (2007) unitary solution to our newly derived 2-factor solution, we found that the items included in our adaptability scale corresponded to the CD-RISC-10. Specifically, the 8-item adaptability factor shared 6 items with Campbell-Sills and Stein’s “hardiness” themed scale. Interestingly, our adaptability themed factor (and CD-RISC-10) also contained items from the CD-RISC-2, a shortened version shown to reflect resilience aspects such as adaptability and recovery from hardship (Vaishnavi et al., 2007). Given that a moderating effect for the self-efficacy factor was not identified, the 8-item adaptability items present a more psychometrically sound assessment of resilience thus, future studies of resilience (defined as a factor of protection against psychopathology) might consider the use of the adaptability factor when measuring resilience in this cohort.

There are limitations to the current study. The most significant limitation is the current sample was comprised of research volunteers and may not be generalizable to the entire population of veterans with military service since 9/11/01. Additional research is needed to examine the utility of this measure within other veteran and military samples. Further, a point of discussion often raised during attempts at instrument refinement is whether an important feature of a construct is sacrificed in an effort to obtain a shortened version (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007). Earlier research in resilience has pointed to numerous factors important for both protection against the development of psychological illness and adaptability in the face of adversity. While the results of this study supported an 8-item version of the CD-RISC, more work is needed to understand what, if any, additional factors may be associated with adaptive responses to stress and trauma in this population.

Given the interest in developing programs to promote resilience among our military (Lester, McBride, Bliese, & Adler, 2011; Seligman & Fowler, 2011), it may be beneficial to turn to those who have provided military service during times of past conflicts (i.e., Gulf War, Vietnam War) and have demonstrated resilience in the face of hardship and/or distress. Future research should continue to evaluate the related constructs of resilience (using theoretically derived models of resilience), hardiness, and social support in order to ascertain what aspects of responses to trauma can be supported and strengthened.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to the veterans for their participation and the research study staff members for their diligent work and essential contributions to the management of this study. In particular, we would like to acknowledge Perry Whitted, Jeffrey Hoerle, and Rick H. Hoyle for their contributions on this project. This work was supported by the Office of Mental Health Services, Department of Veterans Affairs and a Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health Related Research [supplement to NIMH Grant 5R01MH062482]. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or any of the institutions to which the authors are affiliated.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jonathan R. T. Davidson: honoraria for consulting: Lundbeck, Edgemont, Genentech; honoraria for DSMB service: University of California, San Diego; royalties: Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, Davidson Trauma Scale, Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN), MINI-SPIN, Guilford, McFarland.

Kimberly T. Green, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center; Laura C. Hayward, Syracuse VA Medical Center, Syracuse, New York, USA; Ann M. Williams, Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA; Paul A. Dennis, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Brandon C. Bryan, W. G. Hefner Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salisbury, North Carolina, USA, VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center; Katherine H. Taber; W. G. Hefner Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salisbury, North Carolina, USA, VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Salisbury NC USA, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA; Jonathan R. Davidson, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Services, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Jean C. Beckham, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA, VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC USA; Patrick S. Calhoun, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA, VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC USA;

Contributor Information

Kimberly T. Green, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Laura C. Hayward, Syracuse VA Medical Center, Syracuse, New York, USA

Ann M. Williams, Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA

Paul A. Dennis, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Brandon C. Bryan, W. G. Hefner Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salisbury, North Carolina, USA; VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Salisbury NC USA

Katherine H. Taber, W. G. Hefner Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salisbury, North Carolina, USA; VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Salisbury NC USA; Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA

Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center Workgroup, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Jonathan R.T. Davidson, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Jean C. Beckham, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC USA

Patrick S. Calhoun, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC USA

References

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 2.0) [Computer Program] SPSS; Chicago: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baek H-S, Lee K-U, Joo E-J, Lee M-Y, Choi K-S. Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. Psychiatry Investigation. 2010;7:109–115. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.109. doi:10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown GK, Steer RA. Psychometric characteristics of the scale for suicide ideation with psychiatric outpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory-II. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ranieri WF. Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1988;44:499–505. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499::aid-jclp2270440404>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsika V, Sharpley C, Peters K. How is resilience associated with anxiety and depression? Analysis of factor score interactions within a homogeneous sample. German Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;13:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnano G. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely adverse events? American Psychologist. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnano G, Mancini AD. Beyond resilience and PTSD: Mapping the heterogeneity of responses to potential trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;4:74–83. doi:10.1037/a0017829. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RA, Anstey KJ. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Testing the invariance of a uni-dimensional measure that is independent of positive and negative affect. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:527–533. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.026. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Stein M. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R, Hawkins J, Toumbourou J. Positive youth development in the United States: History, efficacy and links to moral and character education. I. In: Nucci L, Narvaez D, editors. Handbook of Moral and Character Education. Routledge; New York: 2008. pp. 459–483. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell R. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Watson D. Constructing Validity: Basic Issues in Objective Scale Development. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7 doi: 10.1037/pas0000626. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.7.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane-Brink KA, Lofchy JS, Sakinofsky I. Clinical rating scales in suicide risk assessment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;22:445–451. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) Depression & Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for posttraumatic stress disorder: The Davidson Trauma Scale. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar L, Wegener D, MacCallum R, Strahan E. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:272–299. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders. Biometrics Research Department; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss J, Levin B, Cho Paik M. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman WD, Burns WR., Jr. Developing an Adaptability Training Strategy and Policy for the Department of Defense. 2010 (IDA Paper P-4591). Retrived from Defense Technical Information Center website: http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA531765&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf.

- Gillespie B, Chaboyer W, Wallis M, Grimbeek P. Resilience in the operating room: developing and testing of a resilience model. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59:427–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KT, Calhoun PS, Dennis MF, Workgroup, M.-A. R. E. a. C. C. Beckham JC. Exploration of the resilience construct in posttraumtic stress disorder severity and functional correlates in military veterans who have served since September 11, 2001. Journal of Clinica Psychiatry. 2010;71:823–830. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05780blu. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05780blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gucciardi D, Jackson B, Coulter T, Mallett C. Dimensionality and age-related measurement invariance with Australian cricketers. Journal of Sport and Exercise. 2011;12:423–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hayton J, Allen D, Scarpello V. Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods. 2004;7:191–205. doi:10.1177/1094428104263675. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge C, Auchterlonie J, Milliken C. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge C, Castro C, Messer S, McGurk D, Cotting D, Koffman R. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn J. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447. doi:10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle R, Duvall J. Determining the number of factors in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In: Kaplan D, editor. The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. 1 ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2004. p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Nakajima S, Shirai A, Kim Y. Cross-cultural validity of the Connor-Davidson Scale: data from Japanese population; Poster presented at the 25th Annual Meeting; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) Atlanta, GA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen IE, Seedat S. Factor structure of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in South African adolescents. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2008;20:23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabacoff R. Coders ‘ Corner Determining the Dimensionality of Data: A SAS ® Macro for Parallel Analysis Coders ’ Corner. Journal of Business. 1995;4:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser H. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:141–151. doi:10.1177/001316446002000116. [Google Scholar]

- Karairmak O. Establishing the psychometric qualities of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in a trauma survivor sample. Psychiatry Research. 2010;179:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane T, Fairbank J, Caddell J, Zimering R, Taylor K, Mora C. Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshoeui M. Psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) using Iranian students. International Journal of Testing. 2009;9:60–66. doi:10.1080/15305050902733471. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney RK, Gatchel RJ. The SCL-90R evaluated as an alternative to the MMPI for psychological screening of chronic low-back pain patients. Spine. 1991;16:940–942. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobasa SC. Stressful life events, personality, and health: an inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:1–11. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.37.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamond A, Depp C, Allison M, Langer R, Reichstadt J, Moore D, et al. Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;43:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester P, McBride S, Bliese P, Adler A. Bringing science to bear: An assessment of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program. American Psychologist. 2011;66:77–81. doi: 10.1037/a0022083. 10.1037/a0022083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes V, Martins M. Validação factorial da escala de resiliência de Connor-Davidson (CD-RISC-10) para Brasilieiros. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalto. 2011;11:36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J. Strategies for assessing the potential for positive adjustment following trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1991;4:93–111. doi:10.1007/BF00976011. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield A, Bender R, Hourani L, Larson G. Suicidal or self-harming ideation in military personnel transitioning to civilian life. Suicide and life-threatening behavior. 2011;41:392–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00039.x. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Beckham JC, Morey R, Marx C, Tupler LA, Calhoun PS. Factorial invariance of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms across three veteran samples. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:309–317. doi: 10.1002/jts.20344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq War. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notario-Pacheco B, Solera-Martinez M, Serrano-Parra M, Bartolomé-Gutiérrez R, Garcia-Campayo J, Martinez-Vizcaino V. Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-item CD-RISC) in young adults. Health and Quailty of Life Outcomes. 2011;9:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-63. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J, Bernstein I. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R, Goldstein M, Malley J, Rivers A, Johnson D, Southwick S. Risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation in veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;123:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R, Johnson D, Goldstein M, Malley J, Rivers A, Morgan C, et al. Psychosocial buffers of traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, and psychosocial difficulties in Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom: The role of resilience, unit support, and postdeployment social support. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;120:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak R, Southwick S. Psychological resilience in OEF-OIF Veterans: Application of a novel classification approach and examination of demographic and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;133:560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.028. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. doi:10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson G, Neiger B, Jensen S, Kumpfer K. The resiliency model. Health education. 1990;21:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M, Fowler R. Comprehensive soldier fitness and the future of psychology. American Psychologist. 2011;66:82–86. doi: 10.1037/a0021898. doi:10.1037/a0021898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton M, Byrd M, von Kluge S. Measuring resilience in women experiencing infertility using the CD-RISC: examining infertility-related stress, general distress, and coping styles. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.06.007. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C, Stewart A. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley W. A self-administering scale for measuring intellectual impairment and deterioration. Journal of Psychology. 1940;9:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Singh K, Yu X. Psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a sample of Indian students. Journal of Psychology. 2010;1:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi S, Connor K, Davidson JRT. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry Research. 2007;152(2-3):293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.01.006. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2010;64:499–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02130.x. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Lau JF, Mak W, Zhang J, Lui W, Zhang J. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale among Chinese adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011;52:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.010. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Zhang J. Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience (CD-RISC) with Chinese people. Social Behavior and Personality. 2007;35:19–30. [Google Scholar]