Abstract

As immunologists, we are frequently asked to evaluate patients with recurrent infections. These infections can provide us with clues regarding what pathways might be aberrant in a given patient, e.g., specific pyogenic bacteria with Toll-like receptor problems, atypical mycobacteria with interferon gamma receptor autoantibodies, and Candida/staphylococcal infections with cellular immune abnormalities. We present a 55-year-old man who presented to our immunology clinic with onychodystrophy of the toenails and fingernails and recurrent oral–esophageal candidiasis. The differential diagnosis for recurrent yeast infections is complex and includes usual suspects as well as some that are not as straightforward.

Keywords: Antibody deficiency, autoantibodies, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, Good's syndrome, IL-12, interferon alpha, thymoma

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief Complaint

Onychomycosis and recurrent oral–esophageal candidiasis.

History of Present Illness

A 55-year-old man was referred to the University of Virginia Immunology Clinic for onychodystrophy of his fingernails and toenails and recurrent oral–esophageal candidiasis. He had the problem with his toenails since childhood, but this had subsequently spread to involve his fingernails ∼4–5 years ago. Six months previously, he was diagnosed with oral candidiasis and was successfully treated with nystatin. He had no history of antibiotic or corticosteroid usage. One week later, he again developed thrush, and this pattern continued over the next months. Concomitantly, he was evaluated by the Dermatology Department for the onychodystrophy. Fingernail cultures were positive for Candida and his toenails grew dematiaceous mold. He was treated with fluconazole or itraconazole at various times over the past year and noted improvement with these treatments. Again, once the medications were removed, his symptoms returned. His last course of antifungal medication was completed 2 weeks before presenting to our clinic.

During our evaluation, he reported early dysphagia, especially while eating bread. He also described symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and cough that were persistent and exacerbated after both eating and exercising. The cough would resolve with his ongoing antiyeast treatments. He denied constitutional symptoms as well as sinopulmonary, gastrointestinal, blood, bone, central nervous system, or kidney infections. He denied recurrent herpes, varicella, or human papilloma virus infections. Most importantly, he denied infections with Staphylococcus aureus including furunculosis. He had no history of autoimmune disease such as thyroiditis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, although he did report transverse myelitis that developed temporally to receiving the tetanus and influenza vaccinations, ∼17 years before presenting to our clinic. He had no human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk factors.

Physical Examination

On physical examination his oropharynx was without evidence of oral candidiasis. He had no lymphadenopathy and his respiratory exam was normal. Skin examination did not show atopic dermatitis or furunculosis; however, he had significant onychodystrophy of his fingernails and toenails.

Laboratory and Other Diagnostic Findings

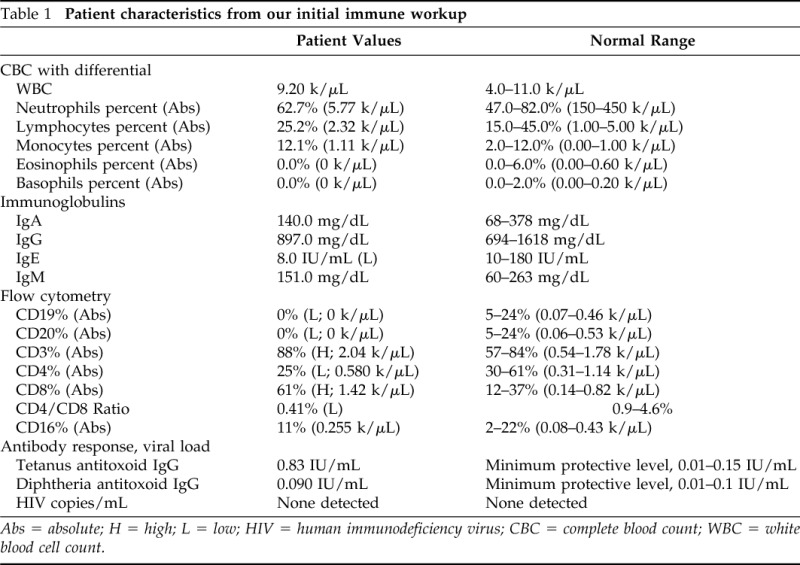

Our initial immunologic evaluation showed absent delayed-type hypersensitivity testing to Candida and Trichophyton, at 48 hours. He was diagnosed with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). His complete blood count revealed normal numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes, but, interestingly, he had no eosinophils or basophils (Table 1). Flow cytometry (Table 1) showed a low CD4:CD8 ratio with low–normal absolute CD4 T-cell numbers (585/μL) but was very surprising for the complete absence of CD19 B cells. The absence of B cells was subsequently confirmed with enumeration of CD20 cells, which were also absent. Because of the absence of B cells, quantitative immunoglobulins were measured and, along with specific antibody testing, these were surprisingly unremarkable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics from our initial immune workup

Abs = absolute; H = high; L = low; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; CBC = complete blood count; WBC = white blood cell count.

Clinical Course

A chest computed tomography scan showed the presence of a large anterior mediastinal mass. He was referred to thoracic surgery for video-assisted thoracoscopy with thymectomy. Pathology showed a noninvasive type B1 thymoma with a lymphocytic predominance but no spindle cells. A repeat computed tomography chest scan at 6 months follow-up did not reveal recurrence of his anterior mass. Interestingly, IgG levels have remained normal postthymectomy and IgG level at 6-month follow-up was 921 mg/dL.

QUESTION 1

What Is the Differential Diagnosis of CMC?

CMC is the result of the failure of T lymphocytes to mount a cellular immune response to Candida, leading to chronic Candida infections that are typically limited to mucosal surfaces, skin, and nails. CMC can present as a manifestation of a wide number of underlying conditions. Most commonly, CMC is a component of the myriad of infections associated with the comprehensive loss of T-cell function that occurs, e.g., in severe combined immune deficiency, DiGeorge syndrome, HIV, etc. Any patient with CMC should be HIV tested. In addition to negative viral load, our patient had normal numbers of CD4 T cells (Table 1), which, along with his age, eliminated severe combined immune deficiency or other acquired or idiopathic CD4 lymphopenias as a mechanism for his disease.

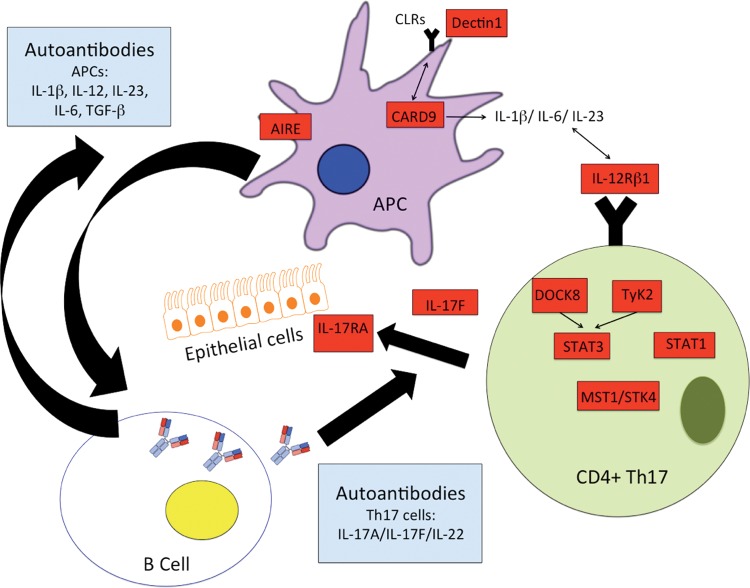

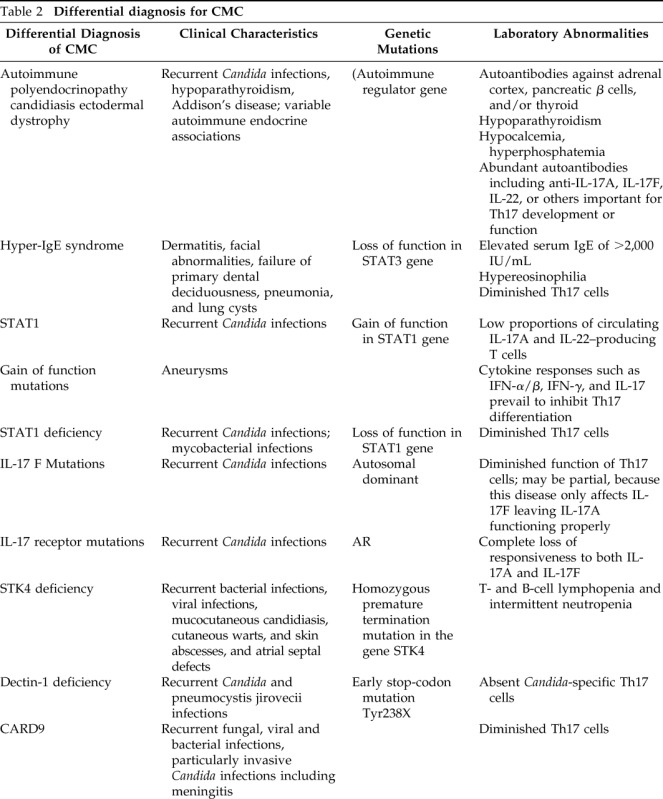

The immune response to Candida requires complex interactions between immune cells and the yeast for adequate recognition, engagement of innate and adaptive immune responses, phagocytosis, and killing. Innate immunity includes a combination of monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and others that together maintain homeostasis with this usual commensal organism, using Toll-like receptors (TLR2 and 4), complement receptors (CR3), and numerous pattern recognition receptors, such as the C-type lectin receptors (CLR; macrophage mannose receptor, Dectin-1, DC-sign, etc.) that are necessary for recognition of mannans and mannoproteins within the cell walls of Candida albicans.1 For the development of adaptive, largely Th17-mediated immunity, binding of Dectin-1 on the surface of dendritic cells signals the CARD9 complex, ultimately activating the production of cytokines including transforming growth factor (TGF) β, IL-6, and IL-23.2 These cytokines provide “signal 3” for the adjacent T cells, which are simultaneously having Candida antigen presented by the dendritic cells. In the context of cellular differentiation, signal 1 refers to major histocompatibility complex/T-helper cell interactions, and signal 2 refers to costimulatory molecules CD80/86 integrating with their respective ligands. Signal 3 represents the cytokine milieu that supports T-cell activation and promotes T-helper immune deviation. In the generation of Th17 cells, the cytokine milieu required includes TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-23. These cytokines signal through tyrosine kinase 2 (Tyk2) to activate the nuclear transcription factor STAT3. These signaling molecules and, especially, STAT3, lead to the production of IL-17 and the differentiation of Th17 cells.3,4 Mutations in genes encoding these proteins and others can lead to Th17 deficiencies and the diagnosis of CMC (Table 2; Fig. 1).

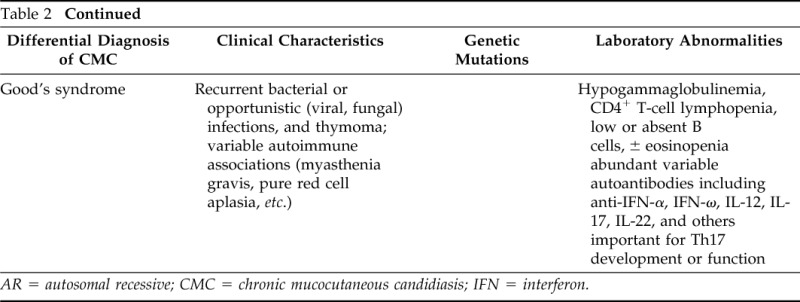

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis for CMC

AR = autosomal recessive; CMC = chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis; IFN = interferon.

Figure 1.

Genetic- and autoantibody-associated mechanisms of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). See text for details. Red boxes designate potential genetic mutations associated with CMC, and blue boxes represent putative autoantibodies.

STAT3-deficient (hyper-IgE syndrome) patients are defined by their markedly elevated IgE levels and, in further contrast to this patient, are generally hypereosinophilic and show susceptibility to skin and respiratory Staphylococcus infections (along with the candidiasis).5 Mutations in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (Dock8) and Tyk2 are also characterized by elevated serum IgE levels, eosinophilia, sinopulmonary staph infections, and lymphopenia along with the CMC. These are autosomal recessive (AR) conditions that are largely distinguished from autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome by the presence of frequent cutaneous viral infections and defects in humoral immunity (e.g., low IgM).6–10

IL-17F deficiency is an autosomal dominant condition in which the host displays impaired (but not abolished) activity against Candida, possibly reflecting the continuing presence of IL-17A. In contrast, IL-17RA deficiency is an AR condition that completely abolishes cellular responses to both IL-17A and IL-17F11 and thereby produces a much more severe defect in anti-Candida immunity. Complete STAT1 deficiency leads to diminished STAT1-dependent cellular responses to both interferon (IFN) α/β as well as IFN-γ. Patients with this disease suffer from both severe viral infections (herpes viruses), as well as intracellular pathogens (Salmonella, BCG, and nontuberculous mycobacteria).12 Interestingly, gain of function autosomal dominant STAT1 mutations can develop infections similar to those with loss of function mutations but can also develop infections with dimorphic molds (Samplaio et al.13) as well as CMC and autoimmunity (Uzel et al.14). Although these patients have increased expression of cytokines that promote Th17 immune deviation (IL-6 and IL-21), ultimately, the stronger cellular responses to the STAT-1 activating cytokines IFN-α/β, IFN-γ, and IL-27 prevail, and their Th1 immune deviating influences supersede and hinder the development of Th17 cells.15 STK4 deficiency was described in a cohort with T and B lymphopenia and histories of multiple bacterial and viral infections (especially cutaneous human papilloma virus), along with CMC16 (Table 2; Fig. 1).

CARD9 is an important part of the pathway engaged by the pattern recognition receptor Dectin-1, which is responsible for initiating many innate immune responses to fungal elements, including, ultimately, the development of Th17 cells as discussed previously.17 Consistent with its essential role as a “danger signal” capable of recognizing Candida-derived fungal elements AR mutations in Dectin-1 and CARD9 have also been associated with the CMC phenotype. However, CARD9 defects are associated less with CMC but instead with severe invasive Candida infections, including meningitis18 (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Finally, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy ectodermal dystrophy results from AR mutations of the autoimmune regulator gene, which in contrast to our patient, is typically characterized by autoimmune hypoparathyroidism and adrenal insufficiency, along with CMC.19 CMC in this population has been linked to presence of autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22,20,21 although diminished intrinsic Th17 responses have also been established.20

QUESTION 2

How Does the Finding of Absent B Cells Affect This Differential?

Absence of B lymphocytes can be seen in numerous conditions and in association with use of rituximab (anti-CD20 antibodies; Table 3). After we discovered our patient had no B cells, we broadened our differential diagnosis to include adult onset X-linked agammaglobulinemia caused by forme fruste mutations in the BTK gene. However, these B-cell deficiencies are not typically associated with CMC, and he lacked any of the typical presenting features suggestive of a humoral immune deficiency. As such, the most likely etiology of his acquired B-cell deficiency is Good's syndrome. Good's syndrome is a rare, adult-onset primary immunodeficiency, characterized by low or absent B cells, hypogammaglobulinemia, and multiple autoimmune diseases in the setting of an underlying thymoma. As with our patient, Good's syndrome patients usually exhibit relative CD4 T-cell lymphopenia (low–normal in our patient), absent eosinophils and basophils, and present in the 4–5th decade of life.22,23 Additionally, our patient presented with symptoms concerning for a mediastinal process (difficulty swallowing). However, Good's syndrome requires deficient IgG antibodies, and, at the time of evaluation, our patient's immunoglobulins were normal, which is inconsistent with this diagnosis (see discussion later in text).

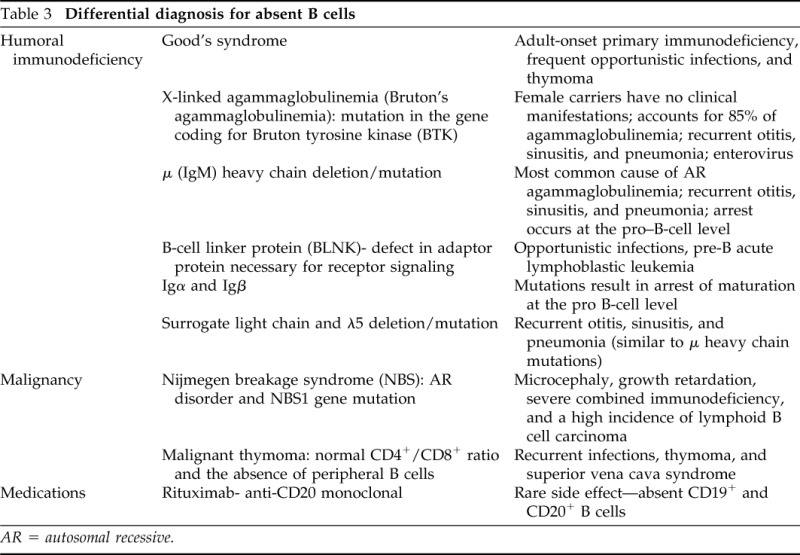

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis for absent B cells

AR = autosomal recessive.

QUESTION 3

What Additional Investigations Would Be Helpful in This Patient to Determine How His Thymoma Produced CMC?

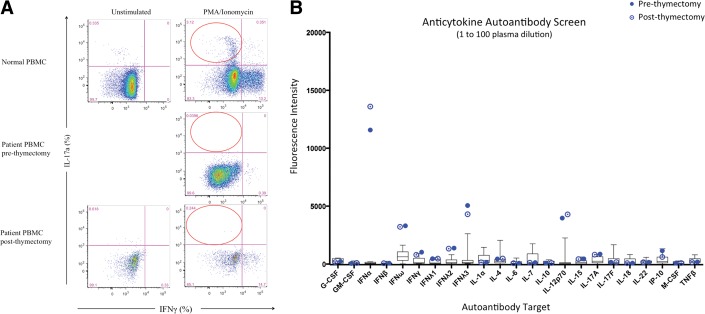

After informed consent, blood samples were taken from the patient. Flow cytometry was performed in the research laboratory at the National Institutes of Health to measure CD4+ T cells expressing intracellular IL-17A, identification markers for Th17 cells. Our patient showed absent Th17 cells compared with the control (3.12%; Fig. 2 A). Because patients with thymoma develop numerous autoantibodies that produce a myriad of autoimmune diseases (Table 4)20,24–26 presumably reflecting the role of the thymus in negative selection of autoreactive cells, we hypothesized that our patient would have autoantibodies to IL-17. We worked with our partners at the National Institutes of Health to evaluate for anticytokine autoantibodies. These studies showed autoantibodies to IFN-α, IFN-ω, IFN-λ3, and IL-12p70 but not to IL-17 (including A and F) or IL-22 (Fig. 2 B). Further testing revealed no evidence of autoantibodies to granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor, IFN-β, IFN-γ, TNF-β, IFN-γ-inducible protein (CXCL10; IP-10), IL-4, IL-6, or IL-15.

Figure 2.

Evidence of Th17 deficiency by flow cytometry and autoantibodies. (A) IL-17a production (%) in CD4+ memory T cells (red circles) for normal (top panels) and patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells pre- and postthymectomy (middle and lower panels, respectively). Unstimulated (left panels) or stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin (right panels) conditions. (Right side of each panel shows interferon [IFN] γ–producing CD4+ memory T cells.) Unstimulated condition not available for prethymectomy sample because of lymphopenia. B) Anticytokine autoantibodies before and after thymectomy. Plasma was mixed with the cognate beads, washed, and tested against human IgG.

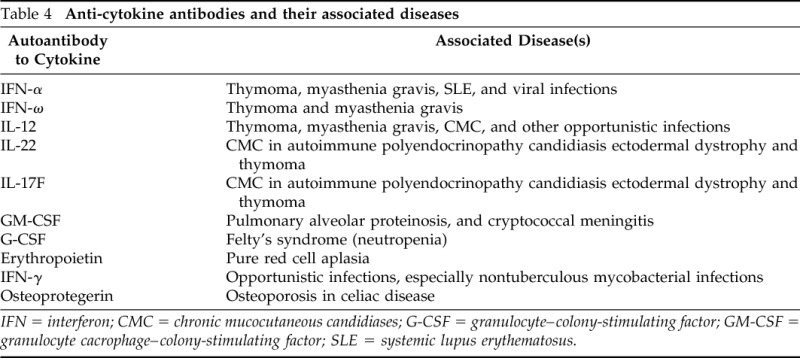

Table 4.

Anti-cytokine antibodies and their associated diseases

IFN = interferon; CMC = chronic mucocutaneous candidiases; G-CSF = granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF = granulocyte cacrophage–colony-stimulating factor; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

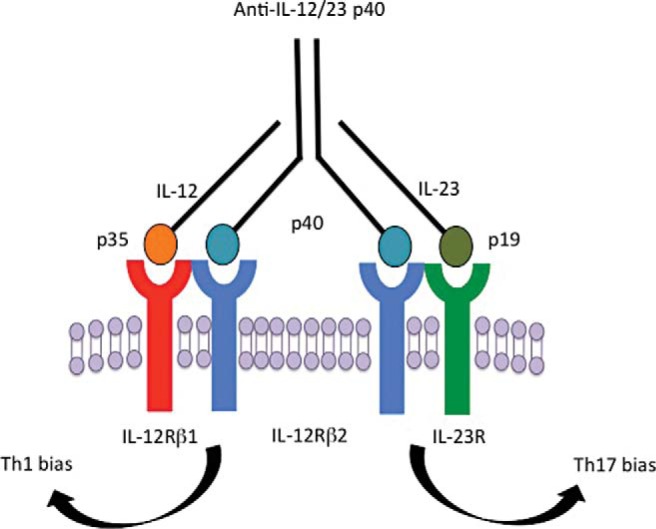

Autoantibodies to IL-17 are thought to be one cause of CMC associated with thymoma, reflecting the subsequent loss of the ability of Th17 cells to carry out their anticandidal (and antibacterial) immune functions.20,25 However, the absence of Th17 cells in our patient could be a reflection of defective T-cell development secondary to thymic dysfunction or could also be ascribed to autoantibodies to cytokines essential for Th17 immune development. Although IL-6 and TGF-β are the most important cytokines necessary for the generation of Th17 cells, other cytokines including IL-23 contribute. IL-23 is a heterodimer consisting of a unique IL-23α chain and the p40 chain of IL-12.27 Thus, autoantibodies to anti–IL-12 are capable of also targeting IL-23. We hypothesize that this could explain our patient's depressed Th17 immunity (Fig. 3). Although we recognize that anti–IL-12p40 autoantibodies are prevalent in thymoma, without necessarily resulting in CMC,28 it is also likely that anticytokine autoantibodies can manifest differently,29 possibly depending on host and environmental factors, as well as differences intrinsic to the autoantibodies themselves.

Figure 3.

The role of autoantibodies to IL-12 in the development of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC). The shared subunit p40 allows for antibody blockade of both Th1 responses via IL-12 and Th17 responses via IL-23. See text for details.

DISCUSSION

We speculated that as with other autoimmune syndromes associated with thymoma (e.g., myasthenia gravis), thymectomy might be associated with loss of his autoantibodies and restoration of his Th17 compartment. Because it is unknown if or even whether this could occur, we decided to start the patient on continuous fluconazole as prophylaxis. However, 1 year after thymectomy, we repeated anticytokine autoantibody testing, and it appears that the autoantibodies persisted against IFN-α IFN-ω, IFN-λ3, and IL-12p70 (Fig. 2 B). At this time, he remains on antifungal prophylaxis to manage his infections.

Surprisingly, despite his absence of B cells, our patient had normal immunoglobulins, reflecting the ongoing presence of long-lived plasma cells. The life expectancy of human plasma cells is presently not known. However, we can expect that at some time in the future he will become the “typical” Good's syndrome patient and develop humoral immune failure. Furthermore, on biopsy, our patient did not have the typical histological finding in the thymus of spindle cells that are associated with Good's syndrome. However, spindle cells are not required for the diagnosis of Good's syndrome, and other cell types within the thymoma have been described, including epithelial cell tumors and/or mixed epithelial/lymphoid tumors.22

The absence of B cells in this disease is thought to also reflect an autoimmune process but, once the B-cell compartment is destroyed, this can never be restored even if these autoantibodies also resolve, presumably reflecting the absence of B lymphocyte stem cells. Although the timing of his humoral immune failure remains unclear, our patient will be monitored closely for infections and will have yearly quantitative antibody titers because we expect him to ultimately need to start replacement immunoglobulin therapy.

Final Diagnosis

This patient has a thymoma associated with autoantibodies to IFN-α and IL-12p70 and CMC. It is possible that his illness may progress in the future to be Good's syndrome.

Footnotes

JL Kennedy received Grants- KL2TR000063; UL1TR000039, ARTrust Minigrant, COBRE pilot project grant 1P20GM103625–02. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare pertaining to this article

REFERENCES

- 1. Netea MG, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Gow NA. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:67–78, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown GD. Dectin-1: A signalling non-TLR pattern-recognition receptor. Nat Rev Immunol 6:33–43, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwakura Y, Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Investig 116:1218–1222, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kimura A, Kishimoto T. IL-6: Regulator of Treg/Th17 balance. Eur J Immunol 40:1830–1835, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chandesris MO, Melki I, Natividad A, et al. Autosomal dominant STAT3 deficiency and hyper-IgE syndrome: molecular, cellular, and clinical features from a French national survey. Medicine 91:e1–19, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Renner ED, Puck JM, Holland SM, et al. Autosomal recessive hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome: A distinct disease entity. J Pediatr 144:93–99, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. New Engl J Med 361:2046–2055, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watford WT, O'Shea JJ. Human tyk2 kinase deficiency: Another primary immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunity 25:695–697, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Minegishi Y, Karasuyama H. Hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome and tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 7:506–509, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minegishi Y, Saito M, Morio T, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity 25:745–755, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science 332:65–68, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chapgier A, Kong XF, Boisson-Dupuis S, et al. A partial form of recessive STAT1 deficiency in humans. J Clin Investig 119:1502–1514, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sampaio EP, Hsu AP, Pechacek J, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain-of-function mutations and disseminated coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 131:1624–1634, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uzel G, Sampaio EP, Lawrence MG, et al. Dominant gain-of-function STAT1 mutations in FOXP3 wild-type immune dysregulation-polyendocrinopathy-enteropathy-X-linked-like syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 131:1611–1623, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu L, Okada S, Kong XF, et al. Gain-of-function human STAT1 mutations impair IL-17 immunity and underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Exp Med 208:1635–1648, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abdollahpour H, Appaswamy G, Kotlarz D, et al. The phenotype of human STK4 deficiency. Blood 119:3450–7347, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gross O, Gewies A, Finger K, et al. Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature 442:651–656, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glocker EO, Hennigs A, Nabavi M, et al. A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. New Engl J Med 361:1727–1735, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Proust-Lemoine E, Saugier-Veber P, Wémeau JL. Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type I. Presse Med 41:e651–e662, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kisand K, Bøe Wolff AS, Podkrajsek KT, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in APECED or thymoma patients correlates with autoimmunity to Th17-associated cytokines. J Exp Med 207:299–308, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Puel A, Döffinger R, Natividad A, et al. Autoantibodies against IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I. J Exp Med 207:291–297, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelleher P, Misbah SA. What is Good's syndrome? Immunological abnormalities in patients with thymoma. J Clin Pathol 56:12–16, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mitchell EB, Platts-Mills TA, Pereira RS, et al. Acquired basophil and eosinophil deficiency in a patient with hypogammaglobulinaemia associated with thymoma. Clin Lab Haematol 5:253–257, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Browne SK, Holland SM. Anticytokine autoantibodies in infectious diseases: Pathogenesis and mechanisms. Lancet Infect Dis 10:875–885, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burbelo PD, Browne SK, Sampaio EP, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies are associated with opportunistic infection in patients with thymic neoplasia. Blood 116:4848–4858, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meager A, Wadhwa M, Dilger P, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies in autoimmunity: Preponderance of neutralizing autoantibodies against interferon-alpha, interferon-omega and interleukin-12 in patients with thymoma and/or myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol 132:128–136, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity 13:715–725, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meager A, Vincent A, Newsom-Davis J, Willcox N. Spontaneous neutralising antibodies to interferon-alpha and interleukin-12 in thymoma-associated autoimmune disease. Lancet 350:1596–1597, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sim BT, Browne SK, Vigliani M, et al. Recurrent Burkholderia gladioli suppurative lymphadenitis associated with neutralizing anti-IL-12p70 autoantibodies. J Clin Immunol 33:1057–1061, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]