Abstract

Objective:

The relative contributions of arteriogenesis, angiogenesis, and ischemic muscle tissue composition toward reperfusion after arterial occlusion are largely unknown. Differential loss of bone marrow-derived cell (BMC) matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), which has been implicated in all of these processes, was used to assess the relative contributions of these processes during limb reperfusion.

Methods:

We compared collateral growth (arteriogenesis), capillary growth (angiogenesis), and ischemic muscle tissue composition after femoral artery ligation in FVB/NJ mice that had been reconstituted with bone marrow from wild-type or MMP9−/− mice.

Results:

Laser Doppler perfusion imaging confirmed decreased reperfusion capacity in mice with BMC-specific loss of MMP9; however, collateral arteriogenesis was not affected. Furthermore, when accounting for the fact that muscle tissue composition changes markedly with ischemia (i.e. necrotic, fibro-adipose, and regenerating tissue regions are present), angiogenesis was also unaffected. Instead, BMC-specific loss of MMP9 caused an increase in the proportion of necrotic and fibro-adipose tissue, which showed the strongest correlation with poor perfusion recovery. Similarly, the reciprocal loss of MMP9 from non-BMCs showed similar deficits in perfusion and tissue composition without affecting arteriogenesis.

Conclusions:

By concurrently analyzing arteriogenesis, angiogenesis, and ischemic tissue composition, we determined that the loss of BMC or non- BMC derived MMP9 impairs necrotic and fibro-adipose tissue clearance after femoral artery ligation, despite normal arteriogenic and angiogenic vascular growth. These findings imply that therapeutic revascularization strategies for treating PAD may benefit from additionally targeting necrotic tissue clearance and/or skeletal muscle regeneration.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is caused mainly by atherosclerotic lesions and is widely prevalent in the aged population (20% asymptomatic and 6% symptomatic prevalence in those >65 years of age1). Arterial occlusions can ultimately lead to the symptomatic consequences of intermittent claudication and critical limb ischemia (CLI), both significant causes of morbidity and mortality. Asymptomatic disease can be attributed to the endogenous capacity of some patients to compensate for widespread occlusive disease. Thus, one potential treatment for established PAD in symptomatic patients is to therapeutically stimulate neovascularization. Endogenous compensation for arterial occlusion comes from a confluence of three processes. First, the pre-existing small arterial pathways that originate upstream of and bypass the occlusion(s) undergo arteriogenesis (i.e. outward remodeling), thereby decreasing upstream resistance and increasing flow downstream2. Second, in the tissue downstream of the occlusion(s), hypoxia induces the expansion of the capillary network via angiogenesis to improve blood flow distribution. Both adaptive arteriogenesis and angiogenesis can ameliorate the symptoms of PAD, and using a myoglobin overexpressing transgenic mouse model, we have recently shown that impaired angiogenesis can lead to a deficit in reperfusion, even in the presence of normal collateral arteriogenesis3. In patients, diseases that impair both processes are known to contribute to symptomatic PAD4,5. Third, although often overlooked6, the tissue injured by the ischemia must be cleared and undergo regeneration to return to functional capacity. In both clinical PAD and analogous animal models (i.e. hindlimb ischemia), the ischemic tissue is located in the lower limbs. Previously overlooked differences in necrotic tissue clearance and myocyte regeneration in response to ischemia7 may be as important as the more widely studied elements of collateral structure and vascular remodeling differences8,9. Ultimately, all three elements must work together to allow for full reperfusion and recovery; however, they are rarely examined in tandem.

Here, we examined the relative roles of arteriogenesis, angiogenesis, and ischemic tissue composition in establishing functional reperfusion by focusing on models involving matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), an enzyme hypothesized to regulate all three processes. Bone marrow-derived cell (BMC) specific loss of MMP9 impairs reperfusion 10–13, with BMC derived MMP9 regulating neovascularization in response to ischemic injury through mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells12,13 and angiogenesis10. BMC-derived MMP9 may also be involved in arteriogenesis, though the results are conflicting14,15. MMP9 is primarily BMC-derived, with neutrophils being the most prevalent MMP9 cell source11,16,17. However, given that neutrophils have a limited role in the angiogenic18 and arteriogenic processes19,20 in response to arterial occlusion, the role of MMP9 may lie in regulating the clearance of injured tissue and muscle regeneration. MMP9-depedent ECM degradation and remodeling allow for proper satellite cell activation and muscle regeneration during injury21. One complication in assessing these elements individually is that altered angiogenesis and impaired skeletal muscle regeneration are often correlated. Detailed analyses of both are required to dissect underlying impairment(s)18. Given this evidence, we hypothesized that the primarily role of MMP9 in ischemic muscle injury due to arterial occlusion is neither through arteriogenesis nor angiogenesis, but instead through tissue clearance and regeneration. Consistent with this hypothesis and contrary to previous findings10,13,22, we found no angiogenic or arteriogenic impairments in MMP9 deficient mice. Rather, impaired reperfusion was best correlated with enhanced necrotic and fibro-adipose tissue composition, providing evidence that non-vascular remodeling function may serve as an additional target for PAD revascularization therapies.

Methods

Animals and Bone Marrow Transplantation

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia and conformed to NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Wild-type (WT) control (FVB/NJ) and MMP9−/− (FVB.Cg-Mmp9tm1Tvu/J) male mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in the animal facilities at the University of Virginia. Bone marrow cell (BMC) transplantations were performed as previously described 23,24. Donor mice were anesthetized by i.p injection of 120 mg/kg ketamine, 12 mg/kg xylazine, and 0.08 mg/kg atropine and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Host mice were anesthetized by inhaled isolflurane before i.v. bone marrow injection. Further details are provided in “Supplemental Materials and Methods” in the Appendix. Henceforth, bone-marrow chimeric mice are identified using a “BMC donor strain→host strain” nomenclature.

Femoral Artery Ligation Model, Perfusion Measurements, and Tissue Processing

Mice for these procedures were anesthetized via i.p injection of 120 mg/kg ketamine, 12 mg/kg xylazine, and 0.08 mg/kg atropine. Femoral arterial ligation (FAL) was performed to induce collateral remodeling in the gracilis adductor muscle and produce a moderate level of ischemia in the downstream tissue in a method similar to that previously described 23,25,26. To control for the effect of surgery, all mice received a sham operation, wherein the femoral artery was exposed but not ligated on the contralateral limb. Animals received injections of bupernorphine for analgesia immediately post-FAL and 8-12 hours later. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging was performed to monitor blood flow recovery in response to FAL as previously described at days 2, 4, 7, 10, and 14 post-FAL prior to terminal harvesting for tissue cross sectional and collateral artery analysis 23,25. Time points are noted as relative to FAL, which is noted as day 0. All animals received unilateral FAL in the left limb, while receiving a sham (control) operation in the right limb to account for the affects of surgical intervention. For tissue and collateral artery morphology analysis, , mice were anesthetized at specified time points after FAL (day 3, 7, 10, or 14 post-FAL) and the gracilis muscle vasculature was vasodilated by superfusing the tissue with adenosine via a simple drip system. Mice were then euthanized by anesthetic overdose and perfusion fixed via cardiac cannulation. Gracilis and calf muscles, including the gastrocnemius and plantaris muscles, were harvested. Further details are provided in “Supplemental Materials and Methods” in the Appendix.

Collateral Artery Network Analyses

Perfusion fixed gracilis muscles were immunoflourescently stained for smooth muscle alpha actin, whole-mounted, and imaged with a fluorescence microscope. Diameter was measured along the two primary collateral artery pathways that span the gracilis muscle. Further details are provided in “Supplemental Materials and Methods” in the Appendix.

Cross-Sectional Analyses

Paraffin embedded gracilis muscles were cross-sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for measurements of cross sectional collateral structure or with picrosirius red for collagen content. Additional gracilis muscle sections were immunostained for CD45 (pan-leukocyte marker), MMP9, CD31 (endothelial cells), and/or Mac-3 (macrophage marker), microscopically imaged, and analyzed. Calf muscles (gastrocnemius and plantaris muscles) were cross-sectioned as well. H&E staining was used to classify ischemic muscle tissue regions as necrotic, regenerating, fibro-adipose, or mature, while immunostaining for the endothelial marker CD31 was used to assess angiogenesis. Further details are provided in “Supplemental Materials and Methods” in the Appendix.

Statistics

All results are reported as ± standard error of the mean. All images were randomized and de-identified to enable blinded analysis. All data were first tested for normality. Statistical significance was assessed by one- and two-way ANOVA, followed by paired comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparisons (SigmaStat 3.5, Systat Inc). Co-variance with laser Doppler perfusion measurements was assessed by Spearman’s correlation. Significance was assessed at P<0.05.

Results

Loss of BMC-Derived MMP9 Impairs Perfusion Recovery After FAL, But Does Not Alter Arteriogenesis

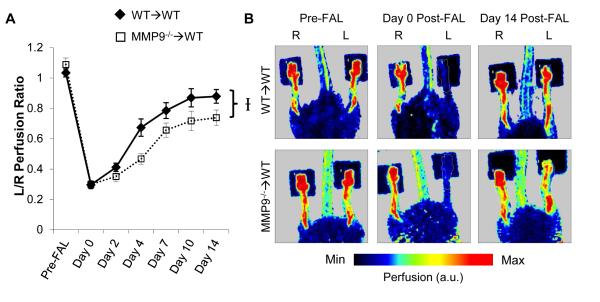

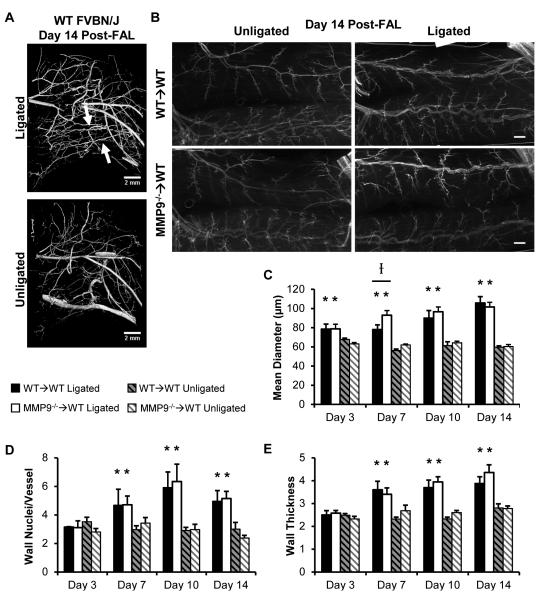

BMC-specific MMP9 deletion inhibited perfusion recovery (Fig 1, p=0.018 between WT→WT and MMP9−/−→WT groups over time; WT→WT: 1.03±0.03, 0.30±0.03, 0.41±0.03, 0.67±0.06, 0.79±0.05, 0.87±0.06, 0.88±0.04; MMP9−/−→WT: 1.09±0.04, 0.30±0.01, 0.35±0.03, 0.47±0.03, 0.66±0.05, 0.72±0.06, 0.74±0.05. p-value between groups within day: 0.37, 0.96, 0.32, 0.001, 0.036, 0.013, 0.100: for pre-FAL, day 0, 2, 4, 7, 10, and 14 post-FAL, respectively). This FAL model showed moderate ischemia, with a plateau in recovery at ~10 days post-FAL. Similar to C57BL/6 mice26,27, all mice showed characteristic tortuosity and arteriogenesis in the collateral arteries of the gracilis muscle through vascular casting to identify the primary collateral arteries resupplying the downstream tissue in the FVB/NJ strain (Fig 2A, n=4). In both groups, we observed arteriogenesis in the ligated limb when compared to the unligated control limb (Fig 2B). The degree of outward remodeling increased with time ; however, there was little difference between groups (Fig 2C, n=5, 7, 7, 8 in WT→WT and n=5, 5, 6, 7 in MMP9→WT at days 3, 7, 10, and 14 post-FAL, respectively). At day 7 post-FAL, there was a slight, but significant increase in outer diameter within the ligated limbs of the MMP9−/−→WT mice compared to WT→WT controls, but this difference disappeared at later time points (Fig 2C). There were no significant differences in baseline collateral diameter between the chimeric groups. Outward remodeling was matched with an increase in wall mass and wall nuclei (Fig 2D, 2E) by day 7 post-FAL, but there were no significant differences within either the ligated or unligated limbs (n=5, 5, 4, 5 in WT→WT and n=5, 5, 5, 7 in MMP9−/−→WT at days 3, 7, 10, and 14 post-FAL, respectively).

Figure 1.

BMC-specific deletion of MMP9 impairs perfusion recovery after FAL. A) Laser Doppler foot perfusion recovery curve for WT→WT and MMP9−/−→WT groups (n=8 and 7, respectively). B) Representative laser Doppler perfusion images of mice (ligation on left leg, L: stabilized with two-sided tape, dark squares). I p<0.05 between WT→WT and MMP9−/−→WT.

Figure 2.

Arteriogenesis after FAL. A) microCT images of mouse upper hindlimbs at 14 days post-FAL. Arrows indicate primary collateral arteries in the gracilis muscle. B) Whole mounts of smooth muscle α-actin+ (SMαA) collateral arteries. Bars indicate 500μm. C) Bar graphs of collateral artery diameter (n=5-8 per group). D,E) Bar graphs of wall nuclei and vessel thickness (n=4-7 per group). *p<0.05 between ligated and unligated limbs within WT→WT or MMP9−/− →WT mice. I p<0.05 between WT→WT versus MMP9−/−→WT mice within ligated or unligated limbs.

Loss of BMC-Derived MMP9 Does Not Alter Peri-Collateral Collagen Remodeling in Response to FAL

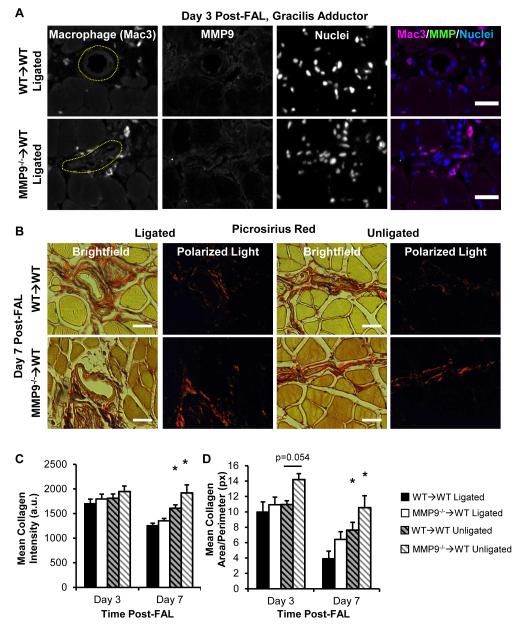

MMP9+ BMCs were not detected in peri-collateral cells recruited during arteriogenesis (Fig 3A, Fig S1 for control, n=6, 7 mice examined for MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups, respectively). Peri-collateral collagen staining is shown in Fig 3B. Both peri-collateral collagen intensity (Fig 3C) and total peri-collateral collagen area (Fig 3D) were decreased by day 7 post-FAL around the remodeling collateral arteries within the ligated limb within both MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups, but there were no significant differences between MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT mice within the remodeling or control (unligated) collateral arteries (n=6, 7 mice for MMP9−/−→WT and n=7, 7 mice for WT→WT, day 3 and 7 post-FAL, respectively).

Figure 3.

BMC-derived MMP9 is not involved in collateral artery matrix remodeling. A) Immunofluorescent staining showed minimal presence of MMP9 around collateral arteries or within Mac+ macrophages (see Fig SI for positive control) at day 3 post-FAL. B) Polarized light birefringence images of picosirious red stained collagen was used to quantify mean peri-collateral collagen intensity (C) and area (D). Bars indicate 25 μm. *p<0.05 between ligated versus unligated limbs within WT→WT or MMP9−/−→WT mice (n=6-7 per group).

Loss of BMC-Derived MMP9 Does Not Alter Leukocyte or Mast Cell Recruitment

We assessed total leukocyte recruitment by CD45 positivity and mast cell density in the mid-zone of the gracilis muscle (Fig S2A, for both CD45 and mast cell analysis, n=5, 5, 5, 5 in WT→WT and n=5, 5, 6, 7 in MMP9→WT at days 3, 7, 10, and 14 post-FAL, respectively). As expected, there was significant recruitment of leukocytes to remodeling collateral arteries within the ligated limb at all time-points (Fig S2B). However, there were no significant differences in pericollateral leukocytes between MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups in either the unligated or ligated conditions. Mac3 labeling suggests these CD45+ cells are predominantly macrophages (Fig 3A). There was no additional increase in toluidine blue positive cells in the remodeling collateral arteries (Fig S2C), and no significant differences between MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups were present.

BMC-Derived MMP9 Production in Response to FAL

BMC recruitment and MMP9 production were assessed in the ischemic calf muscles at day 3. This time point was based on previous findings suggesting the highest degree of MMP9 expression seen in ischemic muscle occurs within the first few days of ischemia11,28. Only ischemic regions with high inflammatory cell infiltrates showed prominent MMP9-positive cell staining (Fig S3, n=6, 7 mice examined for MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups, respectively). As expected, MMP9−/−→WT mice showed negligible MMP9-postive cell staining, constituting a >95% reduction in MMP9-positive cells within infiltrated ischemic tissues at day 3 post-FAL (2.4 ± 1.1 vs 84.2 ± 16.2 MMP9+ cells/high power field for MMP9−/−→WT vs WT→WT mice, respectively, n=5 mice/group) (Fig S3). The infiltrating cells within ischemic tissue predominantly represented macrophages as indicated by Mac3-positive staining. Macrophages, however, were not prominent sources of MMP9 production (Fig S3, top row), as previously demonstrated within ischemic muscle11. Both MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups showed no significant differences in the degree of cellular infiltration within ischemic regions of the muscle at day 3 post-FAL (71.5 ± 3.6% vs 61.6 ± 12.4% infiltrated area of necrotic fibers for MMP9−/− →WT vs WT→WT mice, respectively, assessed from complete H&E stained calf muscle cross sections n=5 mice/group, p=0.37).

Loss of BMC-Derived MMP9 Does Not Alter Angiogenesis in Response to FAL

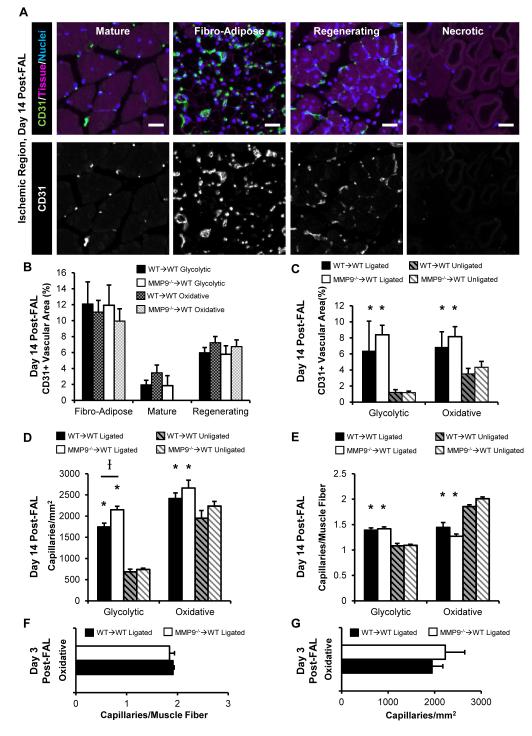

Glycolytic (superficial white gastrocnemius muscle) and oxidative (plantaris and deep gastrocnemius muscle) muscle fiber type regions were assessed for capillary growth29,30. FAL produced non-uniform damage throughout the muscle (Fig S4, day 14 post-FAL). Regions were separated into four types of tissue and vascular structure, based on histological morphology: necrotic tissue, fibro-adipose tissue, regenerating muscle fibers, and mature muscle fibers (Fig 4A). As demonstrated in Fig 4A, necrotic regions completely lacked CD31+ vascular structures. Mature fibers showed the typical organized capillary structure present in skeletal muscle. Regenerating fibers showed a similarly organized capillary network between developing fibers, but with a higher density than mature tissue. Fibro-adipose tissue, however, was largely unorganized. When CD31+ vascular area (proportional to a measurement of capillary density) was quantified per region at 14 days post-FAL, there were broad differences (Fig 4B). Specifically, the vascular area of fibro-adipose tissue>regenerating fiber tissue>mature fiber tissue (Fig 4B). However, the variation in capillary structure between oxidative and glycolytic regions seen at baseline was lost (Fig 4B, 4C). Because necrotic regions were avascular, they were excluded from comparisons of total CD31+ area. As expected, the ischemic tissue showed a greater density of CD31+ vessels in total than the baseline (unligated) state within both glycolytic and oxidative regions (Fig 4C). However, there were no significant differences in vascular area between MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups in either baseline or ischemic tissue in either muscle region (Fig 4C).

Figure 4.

Capillary growth is unaltered in MMP9−/−→WT mice. A-E) Capillary growth was analyzed in calf muscle cross sections at day 14 post-FAL. A) Images of the 4 ischemic tissue morphologies. Bars indicate 25 μm. B,C) Bar graphs of CD31+ area based on tissue type (B) or averaged across all tissue types (C) (n=7,8 mice grouper WT→WT and MMP9−/−→WT group, respectively). D, E) Bar graphs of CD31+ vessels within regions of viable muscle (regenerating or mature fibers) on a per fiber basis for capillary density (D) or capillary to muscle fiber ratio (E) (n=7, 8 mice). F, G) Early time-point analysis of capillary density (F) and capillary to muscle fiber ratio (G) at day 3 post-FAL (n=4 mice per group). *p<0.05 between ligated versus unligated limbs within WT→WT or MMP9−/−→WT mice. Ip<0.05 between WT→WT versus MMP9−/−→WT mice within ligated or unligated limbs.

Capillary to muscle fiber ratio and capillary density were measured within regions of viable muscle fibers (i.e. regenerating or mature muscle) at 14 days post-FAL. Capillary density (Fig 4D) showed a similar relationship to the CD31+ vascular area results. There was a significant increase in capillary density in the ischemic muscle versus the non-ischemic muscle in both MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT mice in the glycolytic and oxidative regions. While there were no significant differences in capillary density in the non-ischemic muscle between MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT mice, there was a slight, but significant, increase in capillary density in the ischemic muscle of MMP9−/−→WT mice versus the WT→WT mice within the glycolytic muscle region. However, when the change in muscle fiber size was accounted for using the capillary to muscle fiber ratio, there were, again, no differences between MMP9−/−→WT and WT→WT groups within non-ischemic or ischemic muscle in either glycolytic or oxidative regions of the muscle (Fig 4E). Further, when the change in muscle fiber size was taken into account, there was an increase in capillarity, indicative of angiogenesis, within the glycolytic region, but a decrease in capillarity in the oxidative region (Fig 4E). To assess early stages of angiogenesis, glycolytic and oxidative regions were additionally assessed at day 3. Similar to the day 14 time point, there were no significant differences in capillary density or capillary to muscle fiber ratio at day 3 post-FAL (Fig 4F, 4G).

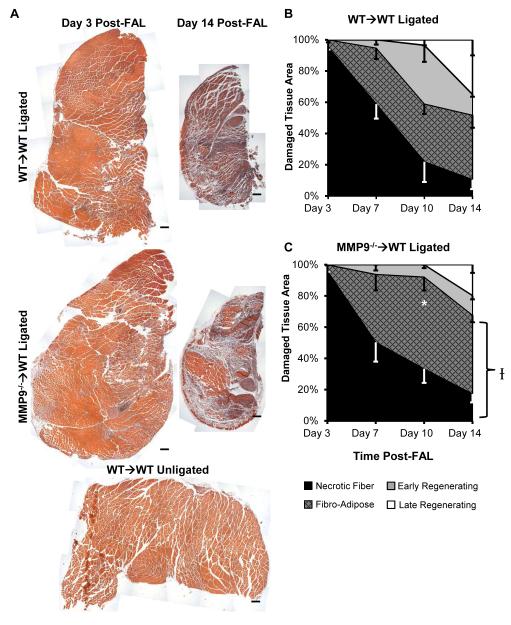

Loss of BMC-Derived MMP9 Affects Ischemic Tissue Composition after FAL

Ischemic muscle tissue composition was determined by histological analysis (Fig 5A). There was a significant impairment in muscle recovery within the MMP9−/−→WT mice versus the WT→WT mice (Fig 5B, 5C, n=5, 7, 7, 8 in WT→WT and n=5, 5, 6, 7 in MMP9→WT in days 3, 7, 10, and 14 post-FAL, respectively). These impairments were most prominent at day 10 post-FAL, where 41.1 ± 12.2% of the damaged tissue had already begun regenerating muscle fibers in WT→WT mice versus only 7.9 ± 2.2 % within MMP9−/−→WT mice (Fig 5C) (p=0.003, n=7 and 6, respectively).

Figure 5.

MMP9−/−→WT mice exhibit impaired skeletal muscle repair within damaged regions. A) Images of H&E stained calf muscle cross-sections. Bars indicate 200 μm. B, C) Tissue composition line graphs. *p<0.05 for total regenerating tissue vs. WT→WT (n=5-8 per group). Ip<0.05 vs. WT→WT across all time points.

Impaired Perfusion Recovery is Associated With Necrotic and Fibro-Adipose Tissue Composition

The percentage of non-viable muscle (i.e. fibro-adipose and necrotic fiber regions) correlated with perfusion (p<0.001, Fig 6A and 6B). However, neither mean collateral diameter (Fig 6C and 6D) nor CD31+ vascular area (Fig 6E and 6F) correlated with perfusion (p=0.536 and 0.416, respectively, n=28 total mice from days 10, 14 post-FAL in WT→WT and MMP9−/−→WT groups).

Figure 6.

Perfusion is related to skeletal muscle repair, but not vascular remodeling. A, C, E) Scatterplots relating perfusion (LDPI ratio) to percent total fibro-adipose and necrotic tissue area, collateral diameter, and approximate CD31+ vascular area. B, D, F) Scatterplots from A, C, and E with linear regressions.

Non-BMC Specific Loss of MMP9 is Similarly Associated with Impaired Reperfusion and Skeletal Muscle Recovery but not Arteriogenesis

WT→MMP9−/− mice also showed impaired perfusion (Fig S5A, n=8, 7, 5 for WT→WT, MMP9−/− →WT, WT→MMP9−/− groups, respectively), but no arteriogenesis deficit (Fig S5B). WT→MMP9−/− mice showed impaired skeletal muscle repair at day 14 compared to WT→WT mice (Fig S5C) that, when pooled with perfusion measurements from WT→WT and MMP9−/− →WT mice (n=20 total), showed significant correlation with necrotic and fibro-adipose tissue area (Fig S5D, p<0.05). WT→MMP9−/− mice showed no correlation between perfusion and collateral diameter (Fig S5E) or approximate total CD31+ area (Fig S5F).

Discussion

We report here that impaired reperfusion in response to FAL can correlate with deficient clearance of injured tissue and/or delayed generation of new muscle, even in the setting of normal vascular responses. We base this central conclusion on three key findings. First, the loss of MMP9 had no detrimental effect on FAL-induced arteriogenesis (Fig 2, Fig S5). Second, when differences in tissue composition were taken into account, we observed no differences in capillary growth within the ischemic tissue of MMP9−/−→WT mice when compared to WT→WT controls (Fig 4). Third, the loss of MMP9 did, however, mar skeletal muscle repair (i.e. injured tissue clearance followed by regeneration) within the distal ischemic tissues (Fig 5, Fig S5). The proportion of necrotic and fibro-adipose tissue showed the strongest correlation with diminished reperfusion (Fig 6, Fig S5). Together, these data suggest that the effects of arteriogenesis, angiogenesis, and tissue clearance/regeneration can be isolated to provide better insight into the mechanisms of the reperfusion response to ischemia. Furthermore, they indicate that, in addition to stimulating collateral arteriogenesis and/or ischemic tissue angiogenesis, therapeutic approaches for stimulating reperfusion in PAD may stand to benefit significantly by targeting improved skeletal muscle repair.

Comparison to Previous Studies and the Need for Detailed Assessment of Angiogenesis and Arteriogenesis

Multiple studies have shown decreased revascularization in hindlimb ischemia with loss of MMP9, with the impairment being primarily attributed to BMC-derived MMP910,12,13. These studies have, however, largely focused on the role of angiogenesis, independent of arteriogenesis and/or skeletal muscle regeneration. Such approaches affect how the role of MMP9 during revascularization is interpreted. For example, increased tissue necrosis is seen in MMP9−/− mice12,13. This could skew metrics such as capillary density and capillary to fiber ratio if necrotic fibers are not excluded31, leading to capillary to fiber ratios significantly below those expected for viable muscle13,31. Further, even within normal and regenerating tissue tissue, muscle fiber-size alterations can affect capillary density31, making such metrics difficult to interpret 10. Here, using detailed analyses to account for these confounding factors, we show there is no shift in capillary to muscle fiber ratio or capillary density within tissue-type regions, thereby suggesting no angiogenic impairment with loss of MMP9. Nonetheless, while these additional considerations may impact how previous studies are interpreted, there is still clear evidence that loss of MMP9 impairs reperfusion and that this is linked specifically to altered BMC function10,13. These previous findings are clearly supported by the current study (Fig 1). Another possible explanation for diminished reperfusion capacity in MMP9−/−→WT mice was deficient upper hindlimb arteriogenesis. Our arteriogenesis analysis was facilitated by careful selection of an FAL model that, while not demonstrating the same degree of ischemia observed with femoral artery excision26, did yield consistent gracilis collateral arteriogenesis outside of the ischemic zone9. Because our FAL model still induced muscle necrosis and capillary regrowth within the damaged tissue regions, similar to the restricted and heterogeneous necrosis seen in clinical disease6,32, this FAL model may actually serve as a closer clinical indicator. Further, such an approach has been previously useful to confirm or exclude the involvement of arteriogenesis in the reperfusion response26,27,33. Here, we showed that, unexpectedly, MMP9−/− →WT mice exhibit fully functional arteriogenesis. When considered in light of the angiogenesis data, this leads us to conclude that impaired reperfusion in MMP9 deficient mice is not due to broadly defective vascular growth.

Importance of Tissue Clearance and Skeletal Muscle Regeneration

The significant deficit seen in skeletal muscle repair with loss of MMP9 suggests it should be carefully considered (see “Supplemental Discussion” in the Appendix and Fig S6 for potential roles of BMC and non-BMC derived MMP9 in response to ischemia). Nonetheless, the lack of correlation between perfusion and both vascular area and collateral diameter does not exclude their requirement for reperfusion or muscle regeneration. Instead, our data suggest that different tissue compositions (i.e. normal, regenerating, necrotic, and fibro-adipose) have different capacities for enabling reperfusion because microvascular network topology, morphology, and density are intrinsically linked to tissue composition. This is perhaps not surprising because treatments that expand microvascular networks without maintaining normal topologies and/or dimensions do not necessarily improve—and may even decrease—reperfusion due to hemodynamic inefficiency34–36. This may explain the paradoxical result that poor reperfusion was observed in mice with a large composition of highly vascularized fibro-adipose tissue. Thus, the promotion of proper skeletal muscle regeneration in combination with the inhibition of fibrosis and adipogenesis in ischemic muscle may yield disproportionate, yet more effective, reperfusion when combined with vascular growth enhancers37. Further, we postulate that the current limited success in clinical trials targeting neovascularization38 stems, at least in part, from an incomplete understanding of how arteriogenesis, angiogenesis, and skeletal muscle regeneration integrate to lead to functional reperfusion.

Lastly, it is important to consider that MMP9 has been primarily proposed as a clinical biomarker for PAD, with increasing MMP9 production linked to increasing disease severity39,40. Our results and previous evidence10,11–13 indicate that loss of MMP9 decreases revascularization potential. These two opposing elements of progression and compensation in response to PAD suggest MMP9 as a challenging target for PAD. However, MMP9 expression seems to peak during the initial ischemic insult and recede upon perfusion recovery11,28, which suggests that MMP9 expression and production are enhanced during active ischemia. Therefore, we postulate that the MMP9 biomarker may be more indicative of increasing ischemic muscle injury, which correlates with increasing severity of PAD. As such, the clinical insight from the current study is neither an altered interpretation of MMP9 as a biomarker for PAD, nor the promotion of MMP9 as a strong target for enhancing tissue perfusion in PAD (see “Supplemental Discussion” in the Appendix and Fig S6). Instead, the central clinical insight is the demonstration that altered tissue skeletal muscle repair alone can have a significant impact on tissue reperfusion. This implies that variations in skeletal muscle regeneration capacity may play a role in determining symptomatic and progressive PAD within certain patient populations. Further, these data suggest that strategies targeting skeletal muscle regeneration in conjunction with targets to enhance vascular remodeling may yield synergistic effects for therapeutic revascularization approaches toward treating PAD.

Asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease can be attributed to endogenous compensation for widespread occlusions, including the lumenal growth of collateral arteries (i.e. arteriogenesis), capillary network expansion via angiogenesis, and the repair of ischemically injured tissue. Here, we examined the relative roles of these 3 processes in establishing reperfusion using models involving matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9). Mice with MMP9 deficient bone marrow-derived cells exhibited impaired reperfusion; however, neither angiogenesis nor arteriogenesis was affected. Instead, impaired reperfusion was strongly correlated with high necrotic and fibro-adipose tissue composition, stressing the importance of stimulating concomitant muscle repair in therapeutic revascularization strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

American Heart Association - 10GRNT3490001, 13GRNT16910073, 09PRE2060385 National Institutes of Health - R01-HL074082, R21-HL098632, T32-GM007297, T32-HL007284

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II) J.Vasc.Surg. :S5–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler M a, Distasi MR, Bills RG, Miller SJ, Alloosh M, Murphy MP, et al. Marvels, mysteries, and misconceptions of vascular compensation to peripheral artery occlusion. Microcirculation. 2010 Jan;17(1):3–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meisner JK, Song J, Annex BH, Price RJ. Myoglobin Overexpression Inhibits Reperfusion in the Ischemic Mouse Hindlimb through Impaired Angiogenesis but Not Arteriogenesis. Am J Pathol. American Society for Investigative Pathology. 2013 Dec;183(6):1710–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Weel V, van Tongeren RB, van Hinsbergh V, van Bockel JH, Quax PH. Vascular growth in ischemic limbs: a review of mechanisms and possible therapeutic stimulation. Ann.Vasc.Surg. :582–97. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins JL, Jones WS, Duscha BD, Allen JD, Kraus WE, Regensteiner JG, et al. Relationship between leg muscle capillary density and peak hyperemic blood flow with endurance capacity in peripheral artery disease. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(1):81–6. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00141.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Z, Swanson SA, Nella A a, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: part 1. Functional and histomorphological changes and evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2008;41(6):481–9. doi: 10.1177/1538574407311106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClung JM, McCord TJ, Keum S, Johnson S, Annex BH, Marchuk D a, et al. Skeletal muscle-specific genetic determinants contribute to the differential strain-dependent effects of hindlimb ischemia in mice. Am J Pathol. Elsevier Inc. 2012;180(5):2156–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalothorn D, Clayton JA, Zhang H, Pomp D, Faber JE. Collateral density, remodeling, and VEGF-A expression differ widely between mouse strains. Physiol Genomics. 2007 Jul;30(2):179–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00047.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholz D, Ziegelhoeffer T, Helisch A, Wagner S, Friedrich C, Podzuweit T, et al. Contribution of arteriogenesis and angiogenesis to postocclusive hindlimb perfusion in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002 Jul;34(7):775–87. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson C, Sung H-J, Lessner SM, Fini ME, Galis ZS. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for adequate angiogenic revascularization of ischemic tissues: potential role in capillary branching. Circ Res. 2004 Feb;94(2):262–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111527.42357.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muhs BE, Gagne PJ, Plitas G, Shaw JP, Shamamian P. Experimental hindlimb ischemia leads to neutrophil-mediated increases in gastrocnemius MMP-2 and -9 activity: a potential mechanism for ischemia induced MMP activation. J Surg Res. 2004 Apr;117(2):249–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heissig B, Rafii S, Akiyama H, Ohki Y, Sato Y, Rafael T, et al. Low-dose irradiation promotes tissue revascularization through VEGF release from mast cells and MMP-9- mediated progenitor cell mobilization. J Exp Med. 2005 Sep;202(6):739–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang P-H, Chen Y-H, Wang C-H, Chen J-SJ-W, Tsai H-Y, Lin F-Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is essential for ischemia-induced neovascularization by modulating bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(8):1179–84. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas TL, Doyle JL, Distasi MR, Norton LE, Sheridan KM, Unthank JL. Involvement of MMPs in the outward remodeling of collateral mesenteric arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007 Oct;293(4):H2429–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakker ENTP, Matlung HL, Bonta P, de Vries CJ, van Rooijen N, Van Bavel E. Blood flow-dependent arterial remodelling is facilitated by inflammation but directed by vascular tone. Cardiovasc Res. 2008 May;78(2):341–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plitas G, Gagne PJ, Muhs BE, Ianus IA, Shaw JP, Beudjekian M, et al. Experimental hindlimb ischemia increases neutrophil-mediated matrix metalloproteinase activity: a potential mechanism for lung injury after limb ischemia• 1. J Am Coll Surg. Elsevier. 2003;196(5):761–7. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heissig B, Nishida C, Tashiro Y, Sato Y, Ishihara M, Ohki M, et al. Role of neutrophil-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 in tissue regeneration. Histol Histopathol. 2010 Jun;25(6):765–70. doi: 10.14670/HH-25.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochoa O, Sun D, Reyes-Reyna SM, Waite LL, Michalek JE, McManus LM, et al. Delayed angiogenesis and VEGF production in CCR2−/− mice during impaired skeletal muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Aug;293(2):R651–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00069.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoefer IE, Grundmann S, van Royen N, Voskuil M, Schirmer SH, Ulusans S, et al. Leukocyte subpopulations and arteriogenesis: specific role of monocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes. Atherosclerosis. 2005 Aug;181(2):285–93. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meisner JK, Price RJ. Spatial and temporal coordination of bone marrow-derived cell activity during arteriogenesis: regulation of the endogenous response and therapeutic implications. Microcirculation. 2010 Nov;17(8):583–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Li Y. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in skeletal muscle: migration, differentiation, regeneration and fibrosis. Cell Adh Migr. 2009;3(4):337–41. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.4.9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heissig B, Hattori K, Dias S, Friedrich M, Ferris B, Hackett NR, et al. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002 May 31;109(5):625–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickerson MM, Burke CW, Meisner JK, Shuptrine CW, Song J, Price RJ. Capillary arterialization requires the bone-marrow-derived cell (BMC)-specific expression of chemokine (C-C motif) receptor-2, but BMCs do not transdifferentiate into microvascular smooth muscle. Angiogenesis. 2009 Jan;12(4):355–63. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickerson MM, Song J, Meisner JK, Bajikar S, Burke CW, Shuptrine CW, et al. Bone marrow-derived cell-specific chemokine (C-C motif) receptor-2 expression is required for arteriolar remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009 Nov;29(11):1794–801. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chappell JC, Song J, Klibanov AL, Price RJ. Ultrasonic microbubble destruction stimulates therapeutic arteriogenesis via the CD18-dependent recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008 Jun;28(6):1117–22. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Distasi MR, Case J, Ziegler M a, Dinauer MC, Yoder MC, Haneline LS, et al. Suppressed hindlimb perfusion in Rac2−/− and Nox2−/− mice does not result from impaired collateral growth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 Mar;296(3):H877–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00772.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalothorn D, Zhang H, Clayton JA, Thomas SA, Faber JE. Catecholamines augment collateral vessel growth and angiogenesis in hindlimb ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(2):H947–59. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00952.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muhs BE, Plitas G, Delgado Y, Ianus IA, Shaw JP, Adelman MA, et al. Temporal expression and activation of matrix metalloproteinases-2, -9, and membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase following acute hindlimb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2003 May;111(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(02)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burkholder TJ, Fingado B, Baron S, Lieber RL. Relationship between muscle fiber types and sizes and muscle architectural properties in the mouse hindlimb. J Morphol. 1994;221(2):177–90. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052210207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki J, Kobayashi T, Uruma T, Koyama T. Strength training with partial ischaemia stimulates microvascular remodelling in rat calf muscles. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;82(3):215–22. doi: 10.1007/s004210050674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudlicka O, Brown M, Egginton S. Angiogenesis in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Physiol Rev. 1992;72(2):369–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedberg B, Angquist K a, Henriksson-Larsen K, Sjöström M. Fibre loss and distribution in skeletal muscle from patients with severe peripheral arterial insufficiency. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1989 Aug;3(4):315–22. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(89)80067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai X, Faber JE. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency causes collateral vessel rarefaction and impairs activation of a cell cycle gene network during arteriogenesis. Circ Res. 2010 Jun 25;106(12):1870–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tirziu D, Jaba IM, Yu P, Larrivée B, Coon BG, Cristofaro B, et al. Endothelial nuclear factor-κB-dependent regulation of arteriogenesis and branching. Circulation. 2012;126(22):2589–600. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.119321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skuli N, Majmundar AJ, Krock BL, Mesquita RC, Mathew LK, Quinn ZL, et al. Endothelial HIF-2α regulates murine pathological angiogenesis and revascularization processes. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1427–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI57322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cristofaro B, Shi Y, Faria M, Suchting S, Leroyer AS, Trindade A, et al. Dll4-Notch signaling determines the formation of native arterial collateral networks and arterial function in mouse ischemia models. Development. 2013;140(8):1720–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borselli C, Storrie H, Benesch-Lee F, Shvartsman D, Cezar C, Lichtman JW, et al. Functional muscle regeneration with combined delivery of angiogenesis and myogenesis factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(8):3287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chilian WM, Penn MS, Pung YF, Dong F, Mayorga M, Ohanyan V, et al. Coronary collateral growth--back to the future. J Mol Cell Cardiol. Elsevier Ltd. 2012;52(4):905–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tayebjee MH, Tan KT, MacFadyen RJ, Lip GYH. Abnormal circulating levels of metalloprotease 9 and its tissue inhibitor 1 in angiographically proven peripheral arterial disease: relationship to disease severity. J Intern Med. 2005 Jan;257(1):110–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hobeika MJ, Edlin RS, Muhs BE, Sadek M, Gagne PJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in critical limb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2008 Sep;149(1):148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.