Abstract

Introduction

Denervation of the paraspinal muscles in spinal disorders is frequently attributed to radiculopathy. Therefore, persons with lumbar spinal stenosis causing asymmetrical symptoms should have asymmetrical paraspinal denervation.

Methods

73 persons with clinical lumbar spinal stenosis, aged 55 to 85, completed a pain drawing and underwent masked electrodiagnostic testing including bilateral paraspinal mapping and testing of 6 muscles on the most symptomatic (or randomly chosen) limb.

Results

With the exception of 10 subjects with unilateral thigh pain (p=0.043), there was no relationship between side of pain and paraspinal mapping score for any subgroups (symmetrical pain, pain into one calf only). Among those with positive limb EMG (tested on one side), no relationship between side of pain and paraspinal EMG score was found.

Discussion

The evidence suggests that paraspinal denervation in spinal stenosis may not be due to radiculopathy, but rather due to stretch or damage to the posterior primary ramus.

Keywords: Spinal stenosis, electrodiagnosis, multifidus, back pain, paraspinal mapping, segmental instability

Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis is the most common reason older persons undergo spine surgery1 and its prevalence is expected to rise as the population ages. The disorder has been a diagnostic dilemma, with arbitrary or unproven radiological criteria widely espoused and cited, even in major trials2–5.

Recently electrodiagnostic testing (EDX), especially the quantified Paraspinal Mapping needle electromyographic protocol for examination of the paraspinal muscles, has been shown to be highly specific and moderately to highly sensitive (depending apparently on severity) to the clinical diagnosis6, 7. While studies have shown denervation of paraspinal and limb muscles in clinically apparent stenosis, these did not always occur together. In one study, of 51 persons with mostly mild to moderate clinical stenosis who underwent paraspinal mapping and examination of 6 limb muscles, 11 had limb fibrillations, 12 had paraspinal fibrillations and 6 had both6. Limb and paraspinal data from a second study is more difficult to sort out but apparently 12 of 28 subjects had limb fibrillations on a 3 muscle examination and 27 of 28 had paraspinal fibrillations7.

A number of possibilities may explain the lack of complete concordance between limb and paraspinal EMG. Purely sacral radiculopathies have no representation in the paraspinal muscles. Also there could be sampling error. Testing of more limb muscles might result in more abnormalities concordant with paraspinal findings. The statistical cutoff for normal paraspinal muscles (paraspinal mapping score <5) may be too stringent. However it is also possible that the paraspinal muscles are involved in a different pathophysiology than the limb muscles. For example it is known that paraspinal muscle denervation occurs in asymptomatic persons 8, 9. This has generated a hypothesis that paraspinal denervation might be caused by stretch of the posterior primary ramus which innervates these muscles, but not the limb muscles10. This stretch and paralysis is thought to predispose to segmental instability, and the instability causes further stretch in a spiral of denervation and joint degeneration.

If the problem is sampling error, we would still expect people with symptoms on one side only to have paraspinal denervation primarily on that side. However if the problem is stretch of the posterior primary ramus, this may be a more symmetrical process despite asymmetry of clinical complaints.

The Michigan Spinal Stenosis Study (MSSS, described in numerous publications, but best summarized in Haig et al 200611 and a subsequent Michigan Spinal Stenosis Study II (which has not yet been described in the literature) contain data on paraspinal mapping bilaterally and on the laterality of symptoms. These data sets can be used to address the question. The purpose of the current paper is to determine whether paraspinal denervation is more prominent on the more symptomatic side in persons with clinically evident lumbar spinal stenosis.

Methods

The study draws data from the Michigan Spinal Stenosis Study, which is a masked study of EDX and MRI in persons with no symptoms, low back pain without stenosis, and clinically evident stenosis. The general methodology of that study and some of the data relating to the current paper is best described in three previous articles6, 11, 12. However, that study focused primarily on persons who were not going to have surgery for their stenosis (and who thus had generally mild to moderate symptoms). A second trial has been undertaken, the Michigan Spinal Stenosis Study II, which recruits asymptomatic volunteers and persons who have been offered surgery for spinal stenosis. While the purposes and details of those studies are complex, the methodology related to the current paper is similar between the studies, as noted below:

All potential subjects were screened prior to enrollment in the study. To qualify, a potential subject must have been between the ages of 55 and 90 years old, and could not: have had prior back surgery; have any history of severe lower limb nerve injury; have severe swelling in the legs; have known personal or familial history of polyneuropathy or other neuromuscular disease; drink an average of more than 12 alcoholic drinks per week; weigh more than 300 pounds; have any implanted electrodes (such as defibrillators), surgical staples, or metal implants that were not MRI-safe; take prescription anticoagulants; or have a condition such as severe heart disease or bad balance that would make it unsafe to complete a walking test. In addition, potential subjects who were not recruited as part of the vascular group could not have diabetes. Specific requirements for each group were as follows.

Persons with apparent clinical lumbar spinal stenosis were obtained through review of records of the physical medicine and rehabilitation, orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery clinics of a university spine program. Potential subjects had a clinical diagnosis of spinal stenosis, symptoms of neurogenic claudication, and claimed difficulty walking 200 yards due to the stenosis symptoms. In order to ensure a certain level of disease severity, for the MSSS-II study persons in this group were required to have been offered surgery by an orthopedic or neurosurgeon. Decision to go through with surgery was not required.

Persons with non-specific low back pain were recruited from clinic schedules at the university’s spine program. Patients being seen at the spine program qualified for the study if they had a primary complaint of low back pain without leg pain, were not thought by their clinicians to have clinical spinal stenosis, had not had previous back surgery, and met all of the eligibility criteria as outlined above.

Subjects were recruited for the vascular group through review of medical records in the vascular surgery and diagnostic vascular clinics. Potential subjects had pain while walking attributed to vascular disease, and were limited to 200 yards or less by their symptoms. Vascular subjects did not have any known spinal stenosis and did not have back pain; due to scarcity of potential subjects without it, subjects in this group were permitted to have diabetes.

Asymptomatic volunteers were recruited through internet postings on the university site as well as in the community. Asymptomatic volunteers were volunteers who met all of the eligibility criteria and who did not have a complaint of back or leg pain.

All subjects filled out an extensive questionnaire. Pertinent to the current study is a pain drawing. These were coded as having pain in the back, gluteal region, thighs, legs, or feet on the right and left. Subsequently the pain drawing results were reclassed as nonlocalized, weak localized, or strongly localized pain. The criteria for each class were as follows: nonlocalized included those whose pain drawings showed markings on the back only (no leg pain), or markings on both legs including one thigh and the opposite lower leg (calf and/or ankle), both thighs, and both lower legs. Weak localized was defined as pain in one thigh only, whereas strong localized was pain in one lower leg only.

In addition to questionnaires, subjects underwent an electrodiagnostic examination by Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation or Neurology specialists who were either board certified or board eligible in Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine. The physicians were not allowed to discuss clinical issues or to perform a physical examination with the subjects, and were thus effectively masked to the subjects’ clinical presentation by a process validated elsewhere 12.

The technical examination included paraspinal mapping needle EMG on both sides. Paraspinal mapping is a quantified, codified needle examination of the L2, L3, L4, and L5 innervated multifidus and muscles sampled incidentally during the approach to these muscles13, 14. Persons who are interested in performing the procedure are advised to read the AANEM course handout14. Briefly, it involves insertion of a 50 to 75 mm monopolar EMG needle through the skin at 4 locations which are 2.5 cm lateral to the spinous process one level below each of these vertebrae. The needle is directed towards spinous process at a 45 to 60 degree depth in short insertions. Reproducible abnormal spontaneous activity is scored 0–4+ in the early part of the insertion, and separately in the last 1 cm of insertion. On contact with the spinous process the needle is withdrawn to the surface and redirected 45 degrees cranially, then on contact with bone again withdrawn and redirected 45 degrees caudally. This results in 4 skin punctures, 12 insertions to the bone, and 24 scores of 0–4, with a total possible score of 96 on one side. Paraspinal mapping has been shown to have excellent test-retest and inter-rater reliability with age related ranges of normal defined through masked testing of asymptomatic volunteers15.

In addition, a 6 muscle EMG on the side determined by a research assistant to be more symptomatic (or if symptoms were symmetrical, by coin toss not observed by the electrodiagnostician). A needle was inserted 6 times in 4 directions to seek abnormal spontaneous activity in each of the following muscles: Gluteus maximus, tensor fascia lata, vastus medialis, tibialis anterior, peroneus longus, and medial gastrocnemius. Spontaneous activity was scored 0–4+ in each muscle using Daube’s criteria. A minimum of 10 motor units were observed in each muscle and the number of polyphasic motor units, subjectively scored, was recorded. EMG testing also included ipsilateral sural and peroneal motor nerve conduction studies and bilateral H-waves.

Results

Two hundred and forty two subjects participated in the MSSS studies, including 99 with clinical stenosis, 57 with mechanical low back pain, 17 with peripheral vascular disease and 69 asymptomatic volunteers. The current study included the group with lumbar spinal stenosis only, and had a final N=73 with complete usable data. Table 1 describes the subject demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics of the sample

| Age (years) (mean, SD) | 65.4 (8.1) |

|

| |

| Sex | 43.3% male |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 86.6% |

| Black | 8.2% |

| Other | 5.2% |

|

| |

| Body Mass Index | 29.0 (5.3) |

|

| |

| Duration of symptoms (years) | 4.4 (6.8) |

|

| |

| Severity of symptoms | |

| Pain Disability Index total | 26.4 (16.5) |

| Visual Analog Pain Scale (average for week) | 4.4 (2.4) |

|

| |

| Limb denervation | 30.6% positive |

There was no significant difference in paraspinal mapping scores on the asymptomatic side when compared to the symptomatic side in any of the groups except the weak localized group, which showed a significant difference between scores (N=10, p = .043). See table 2 for complete results.

Table 2.

Paraspinal mapping scores in subjects with spinal stenosis based on localization of pain

| N | Symptomatic Side/Testing Side (mean, SD) | Asymptomatic Side (mean, SD) | Paired T-test p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-localized | 45 | 4.02 (7.03) | 4.29 (7.14) | .707 |

| Non localized, above knee only | 17 | 4.65 (9.6) | 4.53 (8.2) | .923 |

| Weak Localized | 10 | 5.10 (5.04) | 0.50 (0.97) | .043* |

| Strong Localized | 18 | 3.61 (4.88) | 3.94 (5.06) | .786 |

| Localized pooled | 28 | 3.79 (4.85) | 2.71 (4.39) | .294 |

Note: Non-localized defined as: a) pain in the low back without pain in either leg or b) pain in both thighs or c) pain in both lower legs (calf and ankle/foot), or d) pain in one calf and other thigh

Weak localized defined as: One leg without pain, other leg with pain in thigh

Strong localized defined as: One leg without pain, other leg with pain in lower leg (calf and ankle/foot)

Additional analysis was performed on the group of subjects who were found to have at least one leg muscle with denervation. A total of 22 subjects were included in this analysis. The group as a whole showed symmetrical paraspinal mapping scores, as did all of the subgroups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Paraspinal mapping scores in subjects with spinal stenosis based on localization of pain in subjects with limb denervation based on EMG

| N | Symptomatic Side/Testing Side (mean, SD) | Asymptomatic Side (mean, SD) | Paired T-test p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 22 | 7.92 (9.9) | 7.96 (9.7) | .977 |

| Non-localized | 13 | 7.23 (8.0) | 9.38 (10.4) | .180 |

| Weak Localized | 3 | 6.67 (7.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | .258 |

| Strong Localized | 6 | 3.50 (4.14) | 5.5 (7.5) | .482 |

| Localized pooled | 9 | 4.56 (5.2) | 3.67 (6.5) | .736 |

Note: Non-localized defined as: a) pain in the low back without pain in either leg or b) pain in both thighs or c) pain in both lower legs (calf and ankle/foot), or d) pain in one calf and other thigh

Weak localized defined as: One leg without pain, other leg with pain in thigh

Strong localized defined as: One leg without pain, other leg with pain in lower leg (calf and ankle/foot)

Discussion

The study set out to determine whether paraspinal denervation was higher on the side of worse symptoms in persons with lumbar spinal stenosis. Largely this was found to be not true. Methodology strengths and limitations need to be understood. Implications of this finding, both theoretical and clinical, should be discussed.

Methodology and findings

The study methodology has numerous strengths including masking, reasonable clinical criteria for diagnosis of clinical spinal stenosis, and quantification of EMG findings. Pain drawings are well established measures of pain location for persons with spinal disorders 16. By combining the data from the original Michigan Spinal Stenosis Study with the second trial, the current paper includes a fairly large number of subjects with diverse presentations as well as both back pain and asymptomatic controls. These subjects met typical criteria for spinal stenosis—clinical impression plus imaging. Yet there remains no validated clinical criteria for stenosis, so generalization to populations defined differently may be limited. For example although neurogenic claudication is considered by many to be the hallmark of stenosis, it has not been declared the sine qua non of the diagnosis.

In our study, electromyography was not performed on the limb muscles contralateral to the symptomatic side. If these asymptomatic limb muscles were studied, denervation changes might have supported the theory that stenosis is truly a bilateral process, even when symptoms are not. If the contralateral limb muscles were normal, however, it would lend credence to the hypothesis that the paraspinal denervation on the asymptomatic side is due to isolated stretch of the posterior primary ramus. This is an important area for future exploration.

Scientific and clinical implications

The finding that paraspinal denervation is relatively symmetrical in persons with clinical lumbar spinal stenosis has a number of implications regarding the pathophysiology of spinal stenosis. Over time the pathophysiology of this apparently straightforward disorder has been found to be more difficult to understand. The earliest studies 17 attributed classic symptoms such as neurogenic claudication to a small spinal canal as demonstrated on X-ray. For half a century anatomical measures have been used to ‘diagnose’ stenosis on myelogram, later computer tomography, and most recently magnetic resonance imaging. These include measures of the dimensions or areas of the spinal canal or thecal sac. A number of recent studies including one that includes some persons in the current database, have shown that none of these measures discriminate persons with symptoms from asymptomatic volunteers of the same age group, and that perhaps half of older people in the community meet the previously touted criteria for spinal stenosis6, 7, 18, 19. In retrospect it appears illogical that a static prone test (MRI, computer tomography, or myelogram) would demonstrate the pathophysiology of a disorder when its symptoms often occur only upon standing or walking.

Denervation of the limbs and especially of the paraspinal muscles does not exactly reflect the pathophysiology of the symptom of neurogenic claudication either. EMG has been shown to be a highly specific diagnostic test, with moderate to high sensitivity depending perhaps on the severity of symptoms6, 7. However, denervation as detected on needle EMG is also not something that comes and goes with standing and lying down. Fibrillation potentials represent spontaneous depolarization of a muscle fiber, a phenomenon which only occurs after axonal loss, Wallerian degeneration and reconfiguration of the neuromuscular junction. Fibrillation potentials in the lumbar paraspinal muscles are not thought to appear for 10–14 days following axonal loss, although this has not been prospectively studied in spinal disorders20. The timing of re-innervation and cessation of fibrillation has not been well established. Since fibrillations follow degeneration of the synapse, muscles do not fibrillate and stop fibrillating when a person walks and rest. Denervation is either a consequence of repeated injury or an epiphenomenon or both. Furthermore a process of minor denervation and re-innervation may be a more accurate reflection of this chronic disorder.

The current study finds that paraspinal denervation does not relate well to the side of a pain complaint in persons with spinal stenosis. Spinal stenosis is typically a central phenomenon so there is no reason to believe that all of the nerve damage would be on one side, as one finds with lateral disk herniations. Also, where the pain is in the back or gluteal region one may suspect that this is because the pain is not from nerve, but rather associated facet or sacroiliac or musculoligamentous pain. However pain below the knee is typically neurogenic, and yet persons in this study with unilateral pain below the knee had symmetrical paraspinal denervation. We must conclude that the process of paraspinal denervation is different from the process of neurogenic pain, at least in these cases.

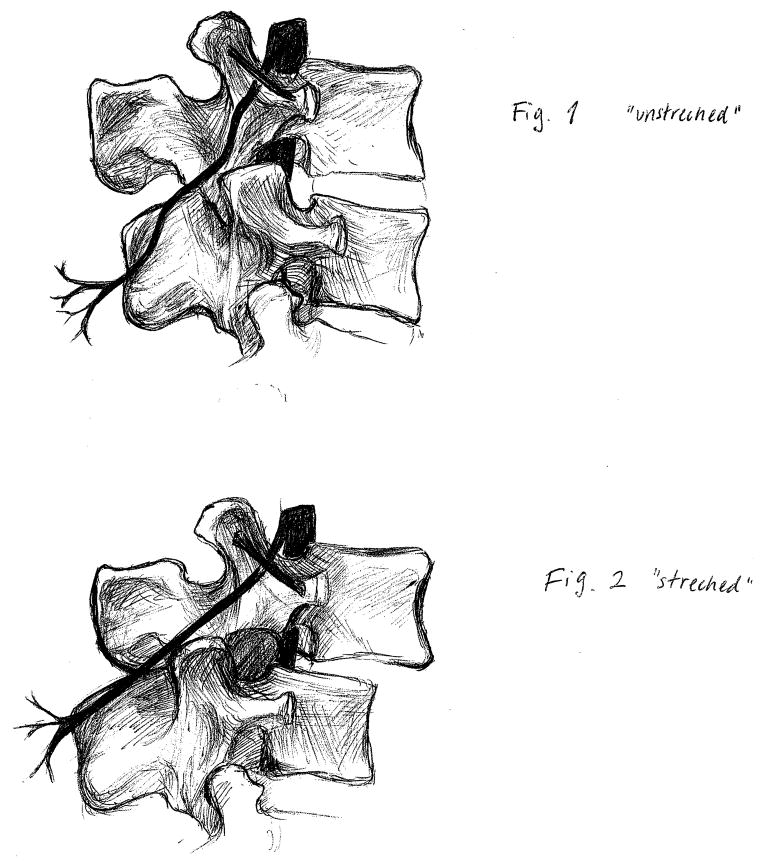

We suspect that the mechanism of this finding may be isolated denervation of the posterior primary ramus. This branch of each lumbar nerve root travels posteriorly, then splits into three branches21. The lateral branch innervates the iliocostalis and the overlying skin. The intermediate branch goes to the longissimus muscle. Important to the current discussion, the medial branch travels to the multifidus muscle, the facet joint, and other structures important to pain. As Figure 1 shows, the posterior primary ramus passes under the mammilo-accessory ligament, an area where some have proposed it can be entrapped or tethered and stretched22, 23. Segmental hypermobility might symmetrically stretch this posterior primary ramus, again illustrated in Figure 1. Whether this in itself causes some aspect of the symptoms of stenosis is not clear. But it apparently is not related to damage to the ventral ramus that goes down the leg.

Figure 1.

Potential explanation for symmetrical paraspinal denervation in stenosis. Segmental hypermobility both compromises the area of the spinal canal and creates tension where the posterior primary ramus travels under the mammilo-accessory ligament. (Figure credit: Karin Roszell)

One theory about spinal stenosis is that symptoms occur as a result of segmental instability. When standing, gravity pulls one vertebra forward on the vertebra below it. This can be resisted by passive resistance of ligaments or active resistance by muscles, either one of which can change as a person stands for a long time or walks. However if there is a shift, the spinal canal becomes smaller, perhaps causing the venous congestion that Porter claims is the pathophysiological mechanism of neurogenic claudication, and that Laban has observed in clinical cases of worsening leg pain at night in persons with congestive heart failure24, 25. We have proposed that this vicious circle of stretch, causing weakness, causing more stretch may be part of the process of lumbar spinal stenosis. This theory was not supported in a study that found no relationship between paraspinal denervation and radiological or clinical progression of stenosis over 22 months10. However that is a relatively short time frame for spinal degenerative processes. The current study provides other evidence that somewhat supports this hypothesis. Scientists may find other ways in the laboratory or clinic to monitor the paraspinal muscles and the posterior primary ramus in relation to clinical spinal stenosis.

The clinical implications of this study are less clear. Regardless of theoretical concerns it remains true that EMG is a good diagnostic test for clinically apparent lumbar stenosis18. There is also increasing evidence that directing epidural injections towards the denervation found on EMG is more effective than not using the EMG data. One might conclude from the current study that paraspinal findings don’t necessarily represent the root damage. So directing an injection or surgery at the level found on paraspinal mapping wouldn’t make sense. However the current study does not adequately address that issue. Posterior primary ramus stretch may still represent the location of the lesion causing symptoms. And it remains possible that compression of roots from stenosis preferentially and symmetrically impacts the paraspinal muscles first.

From a therapeutic standpoint the data contrasts with but does not conflict with the work by Paul Hodges and colleagues. His group found focal asymmetrical atrophy of paraspinal muscles after simple backache (with no apparent neurological involvement) which did not improve after resolution of symptoms, until an exercise program specific to these muscles was implemented26. However, in stenosis at least part of the ‘atrophy’ is denervation. Contrary to at least one book written for the public 27, exercise of the weak paraspinals will not make the nerve root or posterior primary ramus grow back faster. Other goals and other mechanisms of strengthening need to be addressed instead.

Conclusions

Paraspinal denervation does not favor the side of increased symptoms in persons with lumbar spinal stenosis. This supports, but does not prove the theory that a symmetrical process such as stretch of the posterior primary ramus is the cause of some paraspinal denervation. The pathophysiology of spinal stenosis might include a downward spiral of denervation causing stretch of the posterior primary ramus, causing more denervation of the back muscles.

Acknowledgments

“The project described was supported by Award Number R01HD059259 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.”

Abbreviations

- EMG

Electromyography

- EDX

Electrodiagnostic testing

- MSSS

Michigan Spinal Stenosis Study

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- AANEM

American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine

References

- 1.Deyo RA. Trends and Variations in the Use of Spine Surgery. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2006;443:139–146. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000198726.62514.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Keller RB, Chapin AM, Patrick DL, Long JM, et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part III: 1-Year Outcomes of Surgical and Nonsurgical Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. Spine. 1996;21(15):1787–1794. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NASS. Evidence Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care: Diagnosis and Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Burr Ridge. IL: NASS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steurer J, Nydegger A, Held U, Brunner F, Hodler J, Porchet F, et al. LumbSten: The lumbar spinal stenosis outcome study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2010;11(1):254. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, Tosteson A, Blood E, Herkowitz H, et al. Surgical Versus Nonoperative Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Four-Year Results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2010;35(14):1329–1338. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0f04d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haig AJ. Electromyographic and Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Predict Lumbar Stenosis, Low-Back Pain, and No Back Symptoms. Journal of bone and joint surgery. 2007;89(2):358–366. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00704. American volume. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagci I, Gunduz OH, Ekinci G, Diracoglu D, Us O, Akyuz G. The Utility of Lumbar Paraspinal Mapping in the Diagnosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2009;88(10):843–851. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181b333a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Date ES, Mar EY, Bugola MR, Teraoka JK. The prevalence of lumbar paraspinal spontaneous activity in asymptomatic subjects. Muscle & Nerve. 1996;19(3):350–354. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199603)19:3<350::AID-MUS11>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haig AJ, LeBreck DB, Powley SG. Paraspinal Mapping: Quantified Needle Electromyography of the Paraspinal Muscles in Persons Without Low Back Pain. Spine. 1995;20(6):715–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haig AJ. Paraspinal denervation and the spinal degenerative cascade. The Spine Journal. 2002;2(5):372–380. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(02)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haig AJ, Tong HC, Yamakawa KSJ, Parres C, Quint DJ, Chiodo A, et al. Predictors of Pain and Function in Persons With Spinal Stenosis, Low Back Pain, and No Back Pain. Spine. 2006;31(25):2950–2957. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000247791.97032.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haig AJ, Yamakawa KSJ, Parres C, Chiodo A, Tong H. A Prospective, Masked 18-Month Minimum Follow-up On Neurophysiologic Changes In Persons with Spinal Stenosis, Low Back Pain, and No Symptoms. PM&R. 2009;1(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haig AJ. Clinical experience with paraspinal mapping. II: A simplified technique that eliminates three-fourths of needle insertions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1997;78(11):1185–1190. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daube JR. AAEM minimonograph #11: Needle examination in clinical electromyography. Muscle & Nerve. 1991;14(8):685–700. doi: 10.1002/mus.880140802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong HC, Haig AJ, Yamakawa KSJ, Miner JA. Paraspinal Electromyography: Age-Correlated Normative Values in Asymptomatic Subjects. Spine. 2005;30(17):E499–E502. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000176318.95523.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolis RB, Chibnall JT, Tait RC. Test-retest reliability of the pain drawing instrument. Pain. 1988;33(1):49–51. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verbiest H. Pathomorphologic aspects of developmental lumbar stenosis. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 1975;6(1):177–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haig AJ, Tomkins CC. Diagnosis and Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(1):71–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalichman L, Cole R, Kim DH, Li L, Suri P, Guermazi A, et al. Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: the Framingham Study. The Spine Journal. 2009;9(7):545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preston DC, Shapiro B. Electromyography and Neuromuscular Disorders: Clinical-Electrophysiologic Correlations. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. p. 704. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogduk N, Wilson AS, Tynan W. The human lumbar dorsal rami. Journal of Anatomy. 1982;134:383–397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher MA. Electrodiagnostic examination, back pain and entrapment of posterior rami. Electromyography and clinical neurophysiology. 1985;25(2–3):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu PB, Huang SQ, Russel K. The dorsal ramus myotome: Anatomical description and clinical implications in electrodiagnosis. Muscle & Nerve. 1991;14:887–888. [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaBan MM. Restless legs syndrome associated with diminished cardiopulmonary compliance and lumbar spinal stenosis--a motor concomitant of “Vesper’s curse”. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1990;71(6):384–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter RW. Spinal stenosis and neurogenic claudication. Spine. 1996;21(17):2046. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199609010-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodges P, Holm AK, Hansson T, Holm S. Rapid Atrophy of the Lumbar Multifidus Follows Experimental Disc or Nerve Root Injury. Spine. 2006;31(25):2926–2933. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248453.51165.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson J. Treat Your Own Spinal Stenosis. Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing; 2010. Chapter 3: Tune up #1. How to make your back much stronger. [Google Scholar]