Abstract

A major controversy in reading research is whether semantic information is obtained from the word to the right of the currently fixated word (word n+1). While most evidence has been negative in English, semantic preview benefit has been observed for readers of Chinese and German. In the present experiment, we investigated whether the discrepancy between English and German may be due to a difference in visual properties of the orthography: the first letter of a noun is always capitalized in German, but is only occasionally capitalized in English. This visually salient property may draw greater attention to the word during parafoveal preview and thus increase preview benefit generally (and lead to a greater opportunity for semantic preview benefit). We used English target nouns that can either be capitalized (e.g., We went to the critically acclaimed Ballet of Paris while on vacation.) or not (e.g., We went to the critically acclaimed ballet that was showing in Paris.) and manipulated the capitalization of the preview accordingly, to determine if capitalization modulates preview benefit in English. The gaze-contingent boundary paradigm was used with identical, semantically related, and unrelated previews. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found numerically larger preview benefits when the preview/target was capitalized than when it was lowercase. Crucially, semantic preview benefit was not observed when the preview/target word was not capitalized, but was observed when the preview/target word was capitalized.

Keywords: reading, eye movements, semantic preview benefit

It is generally assumed that low-level feature-based properties of words are discarded for more meaningful, abstract letter codes during reading (Rayner & Pollatsek, 1989). In the current study, on the other hand, we investigated the extent to which salient, low-level features of words (e.g., capitalization of the first letter of a word) can modulate how attention is allocated during reading. Specifically, we investigated whether capitalization can (partially) explain differences between English and German with respect to whether readers access and integrate semantic information from upcoming words, prior to fixation.

A major controversy in reading research concerns the extent to which readers obtain semantic information from the word to the right (word n+1) of the currently fixated word (word n). The fact that readers sometimes skip over word n+1 is at least consistent with the argument that it is possible to obtain semantic information from word n+1 (Rayner, 2009). The controversy concerns the case in which word n+1 is not skipped. Here, the evidence is less clear, though much of it indicates that readers of English do not obtain morphological or semantic information from word n+1 (Rayner, 1998, 2009; Schotter, Angele, & Rayner, 2012 for reviews; but see Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014 for German reading). Evidence regarding preview benefit is typically gleaned from the use of the gaze-contingent boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975). In this paradigm, a target word in a sentence is initially replaced with a preview word (or non-word). When the reader's eyes cross an invisible boundary (located just to the left of the target word), the preview changes to the target word, which remains visible for the remainder of the trial. Because the display change occurs during a saccade, when vision is suppressed, readers are generally not aware of the change. The amount of time that readers look at the target word as a function of the nature of the preview is then computed. Preview benefit is the difference between fixation time on the target word when the preview is related subtracted from the time when it is unrelated to the target.

Numerous experiments have demonstrated preview benefit for orthographically and phonologically related previews across different languages (see Schotter et al., 2012 for a review), but, as noted above, semantic preview benefit is more controversial. Rayner, Balota, and Pollatsek (1986) first investigated this possibility in English, using the boundary paradigm and found that a preview that was semantically related (wine) to the target word (beer) did not yield preview benefit, while an orthographically related non-word preview (becn) did. More recently, Rayner, Schotter, and Drieghe (2014) replicated the findings reported by Rayner et al. (1986). Schotter (2013) also replicated a lack of semantic preview benefit for associative relationships, but did find a preview benefit when the preview and target were synonyms (i.e., were identical or very close in meaning; see the General Discussion section below).

Furthermore, other studies with alphabetic languages have likewise not found evidence for semantic preview benefit (Altarriba, Kambe, Pollatsek, & Rayner, 2001; Hyönä & Häikiö, 2005; Rayner, McConkie, & Zola, 1980). However, it appears that the nature of the writing system has an influence on whether or not morphological and semantic preview effects are evident (see Schotter, 2013). While there is no evidence for parafoveal morphological processing in English (Kambe, 2004; Lima, 1987) or Finnish (Bertram & Hyönä, 2007), there is evidence that morphological information is processed parafoveally in Hebrew (Deutsch, Frost, Pollatsek, & Rayner, 2000, 2005). In English, Kambe (2004) found that a nonword preview that shared a prefix (rehsxc) or stem (zvduce) with the target (reduce) provided no facilitation above and beyond the preview benefit provided by a preview that was only orthographically but not morphologically related (e.g., rehsxc—region), indicating that readers of English do not obtain morphological information in the parafovea (see also Lima, 1987). In contrast, Deutsch et al. (2005) found a larger preview benefit in the morphological preview condition compared to the orthographic preview condition for readers of Hebrew, suggesting that they had obtained morphological information from the word, and benefitted from it above and beyond the orthographic relationship between the words. The difference between these results may be due to the differences between these languages; Hebrew has a richer morphological structure than English and morphological constituents are interleaved in Hebrew, instead of concatenated. It is likely that the necessity to decompose and process words in terms of their morphological constituents emphasizes and encourages such processing to occur parafoveally (Schotter et al., 2012).

Evidence from non-alphabetic languages also suggests that properties of the writing system play a crucial role in semantic/morphological preview benefit (see Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014 for a complete review of these studies). It appears that readers of Chinese (a character-based language) do obtain semantic information parafoveally (Yan, Richter, Shu, & Kliegl, 2009; Yang, Wang, Tong, & Rayner, 2012). This is likely because, in Chinese any given word n+1 will be closer to the point of fixation than in alphabetic writing systems because there are no spaces between words and because words are composed of fewer characters in Chinese. Furthermore, Chinese is a morphologically-based language and many characters are composed of radicals, one of which carries semantic information about the word. Because of these semantic radicals, semantically related words are more orthographically similar than in English (e.g., cheese, cat, and trap are all semantically related to, but quite orthographically different from, mouse). Comparing the results from English to those in Chinese and Hebrew suggests that semantic preview benefit is possible, but perhaps only when the orthography of the language encourages or supports it.

More interesting, for our present purposes, are recent reports that semantic preview benefit is observed in German (Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014; Hohenstein, Laubrock, & Kliegl, 2010)1. Again, there may be a property of German orthography that makes semantic preview benefit more likely than it is in English: the first letter of a noun is capitalized in German and the preview/target words in these studies were all nouns. The capitalization of these words may, in fact, draw greater attention to them during parafoveal preview, thus increasing the information obtained from them and, consequently, the preview benefit observed. In fact, early reading researchers (Dearborn, 1906; Huey, 1908) suggested that words with the first letter capitalized may draw increased attention. Hohenstein and Kliegl (2014) did compare preview benefit for words where the first letter was capitalized versus when it was not capitalized in German and found numerically smaller semantic preview benefit effects when the preview/target word was not capitalized, but the effect was significant regardless of capitalization. This is interesting in that the lack of capitalization of nouns in German violates the rules of the orthography (see Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2013 for a review), suggesting that capitalization is not the only property of words that supports semantic preview benefit in German (see Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014; Schotter, 2013). Other suggestive evidence comes from Slattery, Schotter, Berry, and Rayner (2010), who showed that typographical distinctiveness (i.e., capitalization) is detected in the parafovea and can cause words to be processed differently. Their study focused on the phonological processing of abbreviations (NASA, NCAA), which is different than the focus of the present study, but it does provide evidence that distinct and non-standard presentation of letter strings is something that readers are sensitive to parafoveally and may affect the way in which words are processed.

The issue of semantic preview benefit in alphabetic writing systems is theoretically relevant given that it is generally assumed that serial lexical identification models like the E-Z Reader model (Reichle, Pollatsek, Fisher, & Rayner, 1998) would have a hard time dealing with semantic preview benefit effects while parallel activation models like SWIFT (Engbert, Nuthmann, Richter, & Kliegl, 2005) would more readily be able to account for such effects. Actually, Schotter, Reichle, and Rayner (2014) have recently documented that semantic preview effects can be obtained in some circumstances in the context of E-Z Reader. We shall return to this important theoretical issue in the General Discussion.

In the present study we examined the following two questions: (1) would general preview benefit be increased by increased saliency of the preview via capitalization of its initial letter? And (2) would this increase in parafoveal preview by typographical distinctiveness be large enough to cause significant semantic preview benefit in English? To ensure that our target words did not violate English orthography, which potentially would raise the issue of whether subjects employed a different strategy when reading text displayed in an unusual way, we used English target nouns that can legally be presented either capitalized (e.g., We went to the critically acclaimed Ballet of Paris while on vacation.) or not (e.g., We went to the critically acclaimed ballet that was showing in Paris.). We presented previews for these words that matched the target on capitalization and were manipulated for their relationship to the target: identical, semantically related, and unrelated. As noted above, capitalization of the first letter of a preview word might make that word more salient and, hence, result in attention being more focused on it than when it is not capitalized.

Method

Subjects

Sixty University of California, San Diego students participated in the experiment. All were native speakers of English, had either normal or corrected to normal vision, and were naïve concerning the purpose of the experiment.

Apparatus

Eye movements were recorded with an SR Research Eyelink 1000 eyetracker with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. Subjects read sentences displayed on an HP p1230 video monitor with a screen resolution of 1024 × 768 and a refresh rate of 150 Hz. Viewing was binocular, but only movements of the right eye were recorded. Viewing distance was approximately 60 cm, with 2.4 letters equaling one degree of visual angle. A monospace font (Courier New 14) was used to ensure that all words of the same length subtended the same degree of visual angle.

Materials and Design

Sixty target words were selected so that they could be presented with the first letter capitalized or not (e.g., Ballet vs. ballet; see Appendix). For forty of the target words (67%), capitalization of the first letter did not change the meaning of the target word, but rather changed the target noun from a common noun to a proper noun (e.g., the ballet vs. the Ballet of Paris). However, there is a small set of English words for which there are two distinct meanings depending on capitalization (e.g., china cups vs. China the country) and we included twenty targets for which this is the case, in order to investigate whether this affects the pattern of preview benefit effects. For the targets for which the meaning was preserved with capitalization, the same semantically related and unrelated previews were used for each version of the target, but capitalization was manipulated to match the target (e.g., dancer/Dancer were used as semantically related previews and needle/Needle were used as unrelated previews). For the twenty targets that changed meaning depending on capitalization, different semantically related words were selected for the different versions of the target (e.g., plate is semantically related to china and Japan is semantically related to China) but the same unrelated words were used (e.g., magic/Magic; see Table 1). The mean length of the pretarget word was 6.55 characters (range: 4-12); the mean length of the preview/target word was 5.6 (range: 3-10). For all sentences, the words prior to the target were identical between the two versions and the cloze probabilities of the targets and previews were all low (7% for the lowercase target and 0% for all other targets and previews).

Table 1.

Example stimuli used in the experiments. Target words are presented in boldface, but were presented normally in the experiment.

| Stimulus set | Example Sentence | Semantically related preview | Unrelated preview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning preserved with capitalization | We went to the critically acclaimed Ballet of Paris while on vacation. | Dancer | Needle |

| We went to the critically acclaimed ballet that was showing in Paris. | dancer | needle | |

| Meaning changes with capitalization | The woman stated she loved China because it was a beautiful country. | Japan | Magic |

| The woman stated she loved china cups because they always looked delicate. | plate | magic |

Normative data

A group of forty subjects, who did not participate in the reading experiment, rated the words for degree of semantic association on a 9-point scale. Semantically related words were rated significantly higher (MLowercase = 6.5, MCapitalized = 6.8) in degree of association than unrelated words (MLowercase = 2.0, MCapitalized = 2.1; both ps < .001) but there was no difference between the degree of relatedness for capitalized or lower case versions of the words (both ps > .08). Using the gaze-contingent boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975), we manipulated the information available in the parafovea (i.e. the preview word) while subjects were fixating to the left of the target.

Procedure

When subjects arrived, the experimenter explained that they would be reading sentences silently for comprehension. Then the eye tracker was calibrated and the experiment began. Each trial started with a fixation point in the center of the screen that the subject was required to fixate. The experimenter then pressed a button to make the fixation point disappear and a black box appeared on the left hand side of the screen (at the location of the beginning of the sentence). Once the eye tracker detected a fixation inside the box the sentence appeared and the subject started reading. When the eyes moved across the boundary, the preview was replaced by the target word; display changes (the latency from when the boundary was crossed to when the display was updated) were completed, on average, within 3.5 ms (range = 1-7 ms). Five practice sentences, each followed with a comprehension question preceded the experiment. Experimental sentences were interleaved with 15 filler sentences, each with a comprehension question to which subjects responded by pressing a button corresponding to the answer they thought was correct (accuracy was very high, on average 95%).

Results and Discussion

Fixations shorter than 80 ms were combined with a previous or subsequent fixation if they were within one character of each other or were eliminated. Trials in which there was a blink or track loss on the target word or during an immediately adjacent fixation were removed as were trials in which the display change was not completed by the beginning of fixation onset or was triggered early by a saccade that ended left of the boundary. The remaining data (83% of the original number of trials) were evenly distributed over the six conditions (p > .59).

We analyzed a number of standard reading time measures (Rayner, 1998) on the target word: first fixation duration (the duration of the first fixation on a word independent of the number of first pass fixations), single fixation duration (the duration of the fixation when only one fixation is made on a word), gaze duration (the sum of all first pass fixations on a word), go-past time (the sum of all first pass fixations on a word and any fixations, including regressions to earlier parts of the sentence, prior to moving to the right of the target word), total viewing time (the sum of all fixations on the target word including any regressions to it), fixation probability, probability of regressions in, and probability of regressions out of the target word. There were no differences in the probability of fixating the target word (all ps > .12) or conversely, the probability of skipping the target word. Likewise, the probability of making a regression into the target was not affected by any of the manipulations (all ps > .09). The means and standard errors for the target word, aggregated by subject, are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of reading time measures on the target word as a function of target type (capitalized vs. lowercase) and preview condition (identical vs. semantically related vs. unrelated), aggregated by subject.

| Measure | Target | Identical | Preview Semantically Related | Unrelated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Fixation Duration | Capitalized | 213 (5.2) | 230 (5.1) | 231 (5.2) |

| Lower case | 225 (5.2) | 234 (5.0) | 231 (4.3) | |

| Single Fixation Duration | Capitalized | 217 (5.8) | 237 (6.0) | 245 (7.0) |

| Lower case | 231 (5.1) | 244 (6.3) | 238 (4.9) | |

| Gaze Duration | Capitalized | 230 (5.4) | 251 (5.6) | 260 (6.3) |

| Lower case | 245 (6.2) | 257 (6.9) | 259 (6.1) | |

| Total Time | Capitalized | 298 (11) | 338 (11) | 344 (10) |

| Lower case | 298 (9.7) | 328 (10) | 334 (9.5) | |

| Go-Past Time | Capitalized | 266 (8.0) | 287 (7.7) | 308 (10) |

| Lower case | 266 (6.7) | 289 (8.4) | 293 (7.8) | |

| Fixation Probability | Capitalized | .88 (.02) | .90 (.02) | .91 (.02) |

| Lower case | .86 (.02) | .84 (.02) | .88 (.02) | |

| Regressions into Target | Capitalized | .18 (.02) | .28 (.02) | .23 (.02) |

| Lower case | .19 (.02) | .23 (.02) | .22 (.02) | |

| Regressions out of Target | Capitalized | .11 (.02) | .14 (.02) | .15 (.02) |

| Lower case | .07 (.02) | .09 (.02) | .12 (.03) |

The data were analyzed using inferential statistics based on generalized linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) run separately for targets in the capitalized and lowercase conditions. We used different models for the two types of targets in order to demonstrate the preview benefit effects within each capitalization condition most clearly. Within each analysis, preview condition with planned contrasts (see below) were entered as fixed effects and subjects and items were entered as crossed random effects (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008), using the maximal random effects structure (Barr, Levy, Scheepers & Tily, 2013). The planned contrasts of preview were (1) a test for a difference between the identical condition and the unrelated condition (i.e., an identical preview benefit) and (2) a test for a difference between the semantically related and the unrelated condition (i.e., a semantic preview benefit), which were achieved by setting the unrelated condition to the baseline (intercept) and using the default contrasts for each comparison.

To test whether the magnitude of preview benefit differed between the capitalized and lower case versions of the words, we also ran models with the full fixed effects structure; this model included the treatment contrast of capitalization (with the capitalized word as the baseline) and its interaction with the preview contrasts described above. Therefore, the estimates of the main effect of the preview contrasts are the same as those in the capitalized subset model, and the interaction indicates whether the analogous preview contrast in the lower case condition was significantly different from it. For these models, the full random effects structure was too complex for the model to fit. Therefore, we report interactions from the models with only random intercepts.

In order to fit the LMMs, the lmer function from the lme4.0 package (Bates, Maechler & Bolker, 2011) was used within the R Environment for Statistical Computing (R Development Core Team, 2013). For fixation duration measures, linear mixed-effects regressions were used, and regression coefficients (b), which estimate the effect size (in milliseconds) of the reported comparison, and the t-value of the effect coefficient are reported (see Table 3). For transparency, models of untransformed data are reported; log transformations of the duration measures had no effect on the patterns of significance. For binary dependent variables (fixation probability data), logistic mixed-effects regressions were used and regression coefficients (b), which represent effect size in log-odds space, and the z value and p value of the effect coefficient are reported. Absolute values of the t and z statistics greater than or equal to 1.96 indicate an effect that is significant at approximately the .05 alpha level; t and z statistics between 1.69 and 1.95 indicate an effect that is marginally significant (i.e., between the .051 and .091 alpha level).

Table 3.

Results of the linear mixed effects models and logistic regression models for reading time measures on the target. Significant effects are indicated by boldface.

| Measure | Comparison | Capitalized Target | Lowercase Target | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration Measures | b | SE | T | b | SE | t | |

| First Fixation Duration | Identical Preview Benefit | -18.78 | 5.82 | 3.23 | -6.50 | 4.51 | 1.44 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | -3.69 | 4.82 | .77 | 2.44 | 4.37 | .56 | |

| Single Fixation Duration | Identical Preview Benefit | -28.32 | 6.81 | 4.16 | -7.95 | 5.29 | 1.50 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | -11.44 | 6.34 | 1.81 | 2.58 | 5.56 | .46 | |

| Gaze Duration | Identical Preview Benefit | -30.42 | 6.82 | 4.46 | -13.42 | 5.37 | 2.50 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | -10.73 | 6.34 | 1.69 | -4.88 | 6.49 | .75 | |

| Total Time | Identical Preview Benefit | -49.98 | 9.38 | 5.33 | -37.59 | 9.44 | 3.98 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | -6.87 | 9.80 | .70 | -5.66 | 10.72 | .53 | |

| Go-Past Time | Identical Preview Benefit | -44.32 | 9.06 | 4.89 | -26.74 | 8.47 | 3.16 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | -22.32 | 9.35 | 2.39 | -4.99 | 9.58 | .52 | |

| Probability Measures | b | z | P | b | z | p | |

| Fixation Probability | Identical Preview Benefit | -0.05 | .19 | .85 | -0.20 | .86 | .39 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | 0.26 | .93 | .35 | -0.35 | 1.52 | .13 | |

| Regressions into Target | Identical Preview Benefit | -0.29 | 1.69 | .09 | -0.28 | 1.62 | .11 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | 0.26 | 1.50 | .13 | .02 | .11 | .92 | |

| Regressions out of Target | Identical Preview Benefit | -0.14 | .54 | .59 | -0.88 | 3.15 | < .005 |

| Semantic Preview Benefit | 0.14 | .56 | .57 | .39 | 1.67 | .10 | |

Pre-target word

The probability of fixating on the pre-target word ranged between .87 and .89 across the six conditions, with no differences between them (collapsing across the capitalization manipulation, the mean was .88 for the three preview conditions). The means for the gaze duration on the pretarget word were 246 ms, and 249 ms (for the capitalized previews and lowercase previews, respectively) with no difference between them (t < 1.23), indicating that capitalization did not affect the timing of the saccade to the target.

First Fixation Duration

For capitalized targets there was an identical preview benefit; first fixation durations on the target in the identical condition were significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 18.78, SE = 5.82, t = 3.23). However, the semantic preview benefit was not significant—first fixation durations in the semantically related condition were not significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 3.69, SE = 4.82, t < 1). For lowercase targets, neither the identical preview benefit2, nor the semantic preview benefit was significant (both ts < 1.45).

Single Fixation Duration

For capitalized targets, there was an identical preview benefit; single fixation durations on the target in the identical condition were significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 28.32, SE = 6.81, t = 4.16). The semantic preview benefit was marginally significant—single fixation durations in the semantically related condition were slightly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 11.44, SE = 6.33, t = 1.81). For lowercase targets, neither the identical preview benefit nor the semantic preview benefit was significant (both ts < 1.51).

Gaze Duration

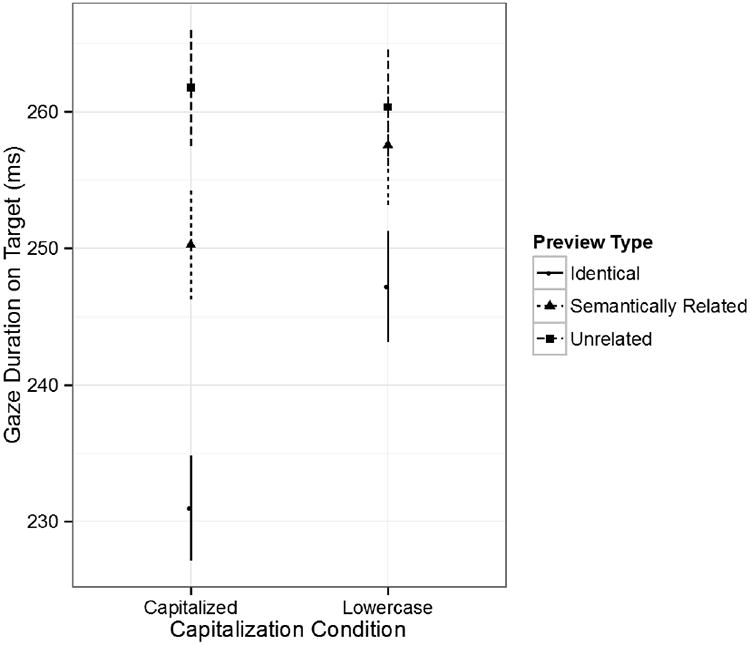

For both the capitalized and lowercase targets, there was an identical preview benefit. For capitalized targets, gaze durations (see Figure 1) on the target in the identical condition were significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 30.42, SE = 6.82, t = 4.46). The semantic preview benefit was marginally significant—gaze durations in the semantically related condition were slightly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 10.73, SE = 6.34, t = 1.69). For lowercase targets, gaze durations in the identical condition were significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 13.42, SE = 5.37, t = 2.50). The semantic preview benefit was not significant—gaze durations in the semantically related condition were not significantly different from the unrelated condition (t < 1).

Figure 1.

Gaze duration on the target as a function of preview type (identical, semantically related or unrelated) and target type (capitalized or lowercase). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Go-Past Time

For capitalized targets, there was an identical preview benefit; go-past time on the target in the identical condition was significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 44.32, SE = 9.06, t = 4.89). The semantic preview benefit was also significant—go-past time in the semantically related condition was significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 22.32, SE = 9.35, t = 2.39). For lowercase targets, there was an identical preview benefit; go-past time in the identical condition was significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 26.74, SE = 8.47, t = 3.16). The semantic preview benefit was not significant—go-past time in the semantically related condition was no different than in the unrelated condition (t < 1).

Total Time

For capitalized targets, there was an identical preview benefit; total time on the target in the identical condition was significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 49.98, SE = 9.38, t = 5.33). The semantic preview benefit was not significant—total time on the target in the semantically related condition was not significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (t < 1). For lowercase targets, there was an identical preview benefit; total time on the target in the identical condition was significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (b = 37.59, SE = 9.45, t = 3.98). The semantic preview benefit was not significant— total time on the target in the semantically related condition was not significantly shorter than in the unrelated condition (t < 1).

Probability of Regression out of the Target

For capitalized targets, there was no difference between the probability of making a regression out of the target in the unrelated condition compared to either the identical condition or the semantically related condition (both ps > .56). Thus the effect seen in go-past time is due to a difference in the amount of time spent rereading prior parts of the text and/or in second pass times on the target, rather than a difference in the rate of regressing. For lowercase targets, there was a significantly lower probability of making a regression out of the target in the identical condition compared to the unrelated condition (z = 3.15, p < .005). There was no difference between the probability of making a regression out of the target in the semantically related condition compared to the unrelated condition (z = 1.67, p = .10), mirroring the pattern seen in go-past time.

Interactions between capitalization and preview benefit

For the duration measures, the only significant interactions between capitalization and the magnitude of the preview benefit was for the identical preview benefit in early reading measures, with smaller identical preview benefits when the word was presented in lower case (FFD: b = -12.39, SE = 5.99, t = 2.07; SFD: b = -18.09, SE = 6.49, t = 2.79; GZD: b = -16.30, SE = 7.42; t = 2.20). Neither of the interactions between capitalization and the identical preview benefit in late reading measures were significant (all ts < 1.38), nor were any of the interactions between capitalization and semantic preview benefit (all ts < 1.50), but all were in the hypothesized direction: preview benefits were larger when the words were capitalized than when they were lower case. For the probability measures, none of the interactions were significant (all zs < 1.26).

As noted above, for two thirds of our stimuli the meaning of the target word was preserved between the capitalized and lower case versions (e.g., ballet vs. Ballet) and we were able to use the same semantically related previews across capitalization conditions (e.g., dancer vs. Dancer). For the other one third of the stimuli, the meaning did change between the capitalized and lower case version (e.g., china cups vs. China the country) and different semantically related previews were used (e.g., Japan for the capitalized target vs. plate for the lowercase target). To assess whether the pattern of data differed between these sets of stimuli for the gaze duration data, we entered stimulus set as a dichotomous variable (centered) and its interaction with the other factors as fixed effects into an LMM with only random intercepts. There was a significant interaction between semantic preview benefit and stimulus set (b = 23.91, SE = 11.14, t = 2.15), but the interaction between identical preview benefit and stimulus set was not significant (b = 17.24, SE = 11.16, t = 1.55). Neither of the three-way interactions between preview benefit (identical or semantic), capitalization condition, and stimulus set was significant (both ts < 1).

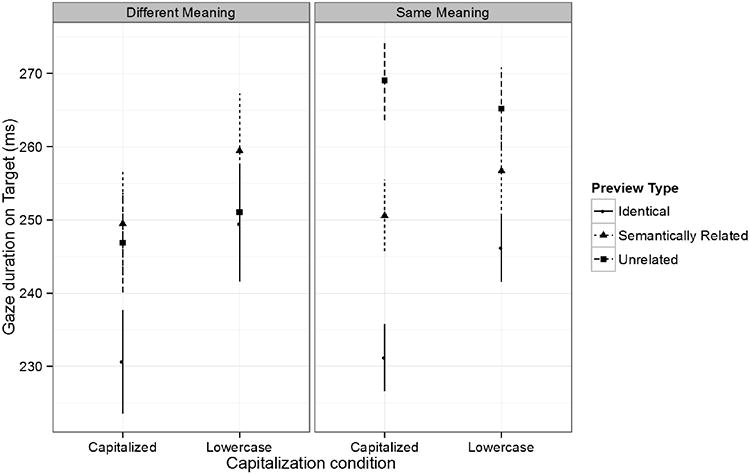

To clarify these interactions, we fit separate LMMs (with capitalization condition and preview entered as crossed fixed effects) for the stimulus set in which the meaning of the target changed with capitalization and when it was preserved. For the stimulus set in which the meaning was preserved, the results were almost identical to those in the full analysis; for the stimulus set in which the meaning did change, none of the effects were significant (Figure 2). The difference in the pattern of data between these two stimulus sets could be due to several reasons, which cannot be distinguished from our dataset. First, the signal-to-noise ratio is lower in the stimulus set for which the meaning of the target changed with capitalization because there are half as many stimuli (i.e., 20) than there were in the stimulus set for which the meaning was preserved (i.e., 40). Second, different semantically related previews were used for the capitalized version compared to the lowercase version for the former stimulus set, but not the latter, also contributing to the variability in the data. Third, the difference in meaning between the fixated target word in the capitalized and lower case versions could have added some degree of ambiguity to the word recognition process, further adding to the variability.

Figure 2.

Gaze duration on the target as a function of preview type (identical, semantically related or unrelated) and target type (capitalized or lowercase) separated by stimulus set. In one set the meaning of the target changed between capitalized and lower case versions (e.g., China vs. china), in the other stimulus set the meaning of the target did not change between capitalization conditions (e.g., Ballet vs. ballet). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Because the purpose of the present study was to test the effect of capitalization, and not the effect of differences in meaning across capitalized and lower case versions, we will focus on the results of the LMM for the stimulus set in which the meaning of the target word was preserved across capitalization conditions (fully crossed fixed effects and random intercepts only). In a model with preview contrasts crossed with capitalization condition, for the capitalized version, there was both a significant identical preview benefit (b = 28.89, SE = 4.56, t = 6.34) and a significant semantic preview benefit (b = 14.59, SE = 4.59, t = 3.18). Neither of the interactions between the preview benefits and capitalization were significant (both ts < 1.61). To further investigate this, we ran models separately for the capitalized condition and lowercase condition, with preview contrasts as the fixed effects and crossed random effects, the identical preview benefit was significant for both the capitalized condition (b = 37.29, SE = 8.25, t = 4.52) and the lower case version (b = 21.12, SE = 6.58, t = 3.21), whereas the semantic preview benefit was only significant in the capitalized condition (b = 18.79, SE = 8.03, t = 2.34) but not in the lower case condition (b = 12. 15, SE = 8.41, t = 1.44).

Taken together, these data confirm our hypothesis that preview benefit in English is enhanced by drawing attention to the preview parafoveally by capitalizing the initial letter. First, note that the effect size of the identical preview benefit (estimated by the effect coefficient (b value) of the model) was always larger for capitalized targets across all measures, suggesting that capitalization of the preview/target attracted more attention than when it was lowercase. In terms of semantic preview benefit, the pattern of data suggests that there was an effect when the preview/target was capitalized (i.e., marginally significant in single fixation duration and gaze duration in the full model, and fully significant in the subset model for which the meaning of the target was preserved across capitalization conditions). Importantly, for all measures, semantic preview benefit was larger for the capitalized target than for the lowercase target.

These data, combined with the results from prior research (e.g., Rayner et al., 1986, 2014; Schotter, 2013) suggest that semantically related (i.e., associated) words in English do not provide semantic preview benefit (when the first letter of the preview/target word is not capitalized). However, when the preview was capitalized, increasing its saliency and consequently the likelihood of readers allocating more attention to it parafoveally, semantic preview benefit was observed.

The effect of launch site on preview benefit

Following Hohenstein and Kliegl (2014) we assessed whether preview benefit decreased with the distance of the prior fixation from the preview (excluding those on the space prior to the word). We then entered this continuous predictor of launch site (centered) to the model and crossed it with the preview manipulation (in both fixed and random effects, using the maximal effects structure) and capitalization condition.

For gaze duration, when launch site was included both the identical preview benefit (b = 30.37, SE = 5.26, t = 5.77) and the semantic preview benefit (b = 10.45, SE = 5.27, t = 1.98) were significant in the capitalized condition. The identical preview benefit in the lowercase condition was significantly smaller than in the capitalized condition (b = 15. 76, SE = 7.51, t = 2.10), but the interaction between capitalization and semantic preview benefit was not significant (t < 1). The main effect of launch site was not significant and it did not interact with the capitalization condition (both ts < 1). In the capitalized condition, the identical preview benefit was significantly affected by launch site (b = 3.42, SE = 1.74, t = 1.97), and this did not significantly differ in the lower case condition (t < 1). In the capitalized condition, the semantic preview benefit was not significantly affected by launch site (t < 1), but the three-way interaction with capitalization condition was marginally significant (b = 4.68, SE = 2.64, t = 1.77). Importantly, when only trials in which the pretarget word was fixated were included in the analysis neither the effect of launch site nor its interaction with any of the other factors were significant (all ts < 1.55), indicating that the effect of launch site was picking up on whether the reader obtained a preview from the pretarget word or not.

General Discussion

Three primary findings emerge from the present study. First, consistent with other studies (Altarriba et al., 2001; Rayner et al., 1986, 2014; Schotter, 2013), we found no evidence of semantic preview benefit for readers of English for semantically related (non-synonym) previews when the first letter of the preview/target word was not capitalized. Second, consistent with our hypothesis that capitalization of the first letter of the preview/target words would draw more attention to a word than standard lowercase letters, we found that, in the identical preview condition, fixation times on capitalized words were shorter than when the word was not capitalized (across all early time measures; all ts > 2.37). Third, we found evidence for semantic preview benefit when the target/preview words were capitalized3; in the full analysis, the effect was only marginally significant in single fixation duration and gaze duration but was fully significant in go-past time (but not in the rate of regressing out of the target). For the subset of the data for which the meaning of the target was preserved across capitalization condition (i.e., the strongest test of our hypothesis) the semantic preview benefit was significant for capitalized preview/targets but was not significant for lower case targets. We will discuss each of these points in turn.

The fact that we found no evidence for semantic preview benefit when the first letter of the preview/target words were not capitalized provides further evidence that such effects may be rather elusive in English. In contrast, orthographic and phonological preview benefit effects are reliable in English reading. As we've noted previously (Rayner et al., 2014; Schotter, 2013; Schotter et al., 2012), in such cases there is a match (and hence a fair amount of overlap) between the preview and target word, and this match underpins preview benefit. More recently, Schotter (2013) demonstrated semantic preview benefit for synonyms, and here too there is a match between the preview and the target word (i.e., a match on meaning). On the other hand, with most semantically related previews there is no match to the target word; they are not similar in either orthography or phonology, and while they are semantically related (i.e., associated with each other), they do not mean the same thing. Thus, the mismatch between orthography and phonology between preview and target might well override any potential benefit due to the semantic relationship between preview and target. We hasten to note that it is quite possible that there are other situations (i.e., other than synonyms) in which semantic preview benefit can be observed, but the present results, along with the findings of Schotter (2013) and Rayner et al. (1986, 2014) suggest that they might not be easy to find.

It is quite interesting that we found that presenting previews (and targets) with the first letter capitalized led to shorter fixations on the target words when there was no display change (i.e., in the identical condition). As we noted earlier, we suggest that capitalization draws more attention to a word before it is fixated, given that it is typographically distinct from other words (see also Slattery et al., 2010) and this causes it to benefit from more preprocessing and thus require less time to process during direct fixation. Dearborn (1906) and Huey (1908) both suggested the possibility that words with the first letter capitalized may increase attention to the word. The results of the present study are consistent with this suggestion.

The fact that we found evidence of semantic preview benefit when the first letter of the preview/target words was capitalized is quite interesting. The semantic preview effects may be due to the preview lending a head-start in activation to the target (akin to semantic priming) that is enhanced when more attention is allocated to the preview via capitalization. This effect was observed for semantic associates in English under this increased salience condition. These effects may be more readily observable in other languages because orthographic properties (e.g., shallow orthography in German and dense text with semantics coded in the orthography in Chinese) may allow for more semantic access parafoveally, and thus more semantic priming-like preview benefit (see Schotter, 2013).

As noted above, it has typically been assumed that evidence for semantic preview benefit would be difficult to accommodate within the context of the E-Z Reader model (Reichle et al., 1998). However, as we also noted, we (Schotter et al., 2014) have recently documented that such effects, while small, can occur within the context of the model. Specifically, our simulations demonstrated that when the pretarget word is relatively easy to process (e.g., is highly predictable and high frequency), more time can be spent preprocessing the target word parafoveally and there will be a greater likelihood of that processing progressing to the L2 stage of the model. We proposed a theoretical framework in which to conceptualize how semantic preview benefit might arise. In that framework, it was suggested that, if the preview is easy to process, enough information is obtained from the prior context and preview that minimal processing of the target transpires once it is fixated (particularly because there is an approximately 60ms lag in visual information reaching the brain); thus, the system may not even register that one word had changed to another, decreasing the likelihood of a disruption in processing and lengthened fixation durations. The simulations in Schotter et al. (2014) focused on what properties of the context and pretarget word (which, in a serial model must be processed before the target) modulate the degree of preprocessing of the target. The present research suggests that there might be salient visual properties of the preview itself that encourage greater preprocessing.

In summary, we found no evidence for semantic preview benefit when English preview/target words did not have the first letter capitalized, confirming prior work. However, we found evidence consistent with semantic preview benefit when the preview/target were capitalized indicating that, in English, a word that has the first letter capitalized draws more attention than when the word is not capitalized, leading to larger preview benefits, in general, and a larger likelihood of semantic preview benefit.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by grants HD065829 and DC000041 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Mike Reiderman for his assistance in collecting the data reported in this article.

Appendix

| Sentence | Related | Unrelated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | We all met at the nearby Airport of San Diego to travel to Europe. | Baggage | Flowers |

| 1 | b | We all met at the nearby airport to travel to Europe. | baggage | flowers |

| 2 | a | Randy was shocked by what the newest Android operating system could do. | Machine | Butcher |

| 2 | b | Randy was shocked by what the newest android was programmed to do. | machine | butcher |

| 3 | a | We wondered if a special Angel Food cake would be a good dessert for the party. | Devil | Shirt |

| 3 | b | We wondered if a special angel would come to protect us. | devil | shirt |

| 4 | a | My sister wanted another Apple computer for her birthday. | iPods | Zebra |

| 4 | b | My sister wanted another apple for an afternoon snack. | grape | zebra |

| 5 | a | Everyone knows that Area 51 is off limits to the public. | Zone | Pore |

| 5 | b | Everyone knows that area has restricted access. | zone | pore |

| 6 | a | The young and brilliant Author of the Year had many good ideas. | Writer | Gravel |

| 6 | b | The young and brilliant author had many good ideas. | writer | gravel |

| 7 | a | We went to the muddy Ranch of the West to buy a cow. | Horse | Baton |

| 7 | b | We went to the muddy ranch to buy a cow. | horse | baton |

| 8 | a | We watched the famous Band of Brothers marathon on television. | Crew | Book |

| 8 | b | We watched the famous band of thieves run away from the bank. | crew | book |

| 9 | a | My mother waited in line at the disorganized Bank of America to get some money. | Coin | News |

| 9 | b | My mother waited in line at the disorganized bank to get some money. | coin | news |

| 10 | a | My friends and I went to the enormous Bay of Bengal for our vacation. | Sea | Fee |

| 10 | b | My friends and I went to the enormous bay on a hot summer day. | sea | fee |

| 11 | a | My friends and I went to the popular Beach Cafe because we heard it was the best. | Shore | Tanks |

| 11 | b | My friends and I went to the popular beach because we heard it was the best. | shore | tanks |

| 12 | a | Mary told me dust off the antique Bible before going to church. | Psalm | Clown |

| 12 | b | Mary told me dust off the antique bible of French cooking before making the souffle. | guide | clown |

| 13 | a | We didn't like the boring Biology of Mammals class we had to take. | Science | Sweater |

| 13 | b | We didn't like the boring biology book the teacher assigned. | science | sweater |

| 14 | a | I watched the loud Black Student Association protest on campus. | White | Truck |

| 14 | b | I watched the loud black crow screech as it hopped across the field. | white | truck |

| 15 | a | I enjoyed the recent Bologna trip with my family. | Italian | Curtain |

| 15 | b | I enjoyed the recent bologna sandwich I had for lunch. | sausage | curtain |

| 16 | a | Dale wanted to know whether Bourbon County was a nice place to live. | Whiskey | Trailer |

| 16 | b | Dale wanted to know whether bourbon would be a good drink to have at a party. | whiskey | trailer |

| 17 | a | Cara wanted to know whether Camp Pendleton was open to the public. | Base | Pole |

| 17 | b | Cara wanted to know whether camp grounds would be sufficient for the vacation. | tent | pole |

| 18 | a | I went down to the lovely Canal of Love to watch the boats. | Water | Grain |

| 18 | b | I went down to the lovely canal to watch the boats. | water | grain |

| 19 | a | Dylan recently learned Cancer is a water sign, which suggests sympathy. | Gemini | Guitar |

| 19 | b | Dylan recently learned cancer rates have been rising over the past years. | tumors | guitar |

| 20 | a | A popular tourist destination is the windy Castle Winchester in England. | Palace | Office |

| 20 | b | A popular tourist destination is the windy castle on a hill in England. | palace | office |

| 21 | a | Marla really enjoyed seeing Cats on Broadway while she was in New York. | Dogs | Star |

| 21 | b | Marla really enjoyed seeing cats play with each other at the shelter. | dogs | star |

| 22 | a | My family and I went to the creepy Cemetery of Solitude while on vacation. | Memorial | Computer |

| 22 | b | My family and I went to the creepy cemetery for my father's funeral. | memorial | computer |

| 23 | a | We wondered if the fashionable Club Med would be a good place for vacation. | Golf | Ring |

| 23 | b | We wondered if the fashionable club would be a great place for a bachelorette party. | beer | ring |

| 24 | a | The rumor is that the other Chief is plotting to attack soon. | Tribe | Couch |

| 24 | b | The rumor is that the other chief concern of the group is that Bob will sell them out. | major | couch |

| 25 | a | The woman stated she loved China because it was a beautiful country. | Japan | Magic |

| 25 | b | The woman stated she loved china cups because they always looked delicate. | plate | magic |

| 26 | a | He said that the local Church of Scientology had many celebrities in it. | Chapel | Hanger |

| 26 | b | He said that the local church had a beautiful altar. | chapel | hanger |

| 27 | a | Sarah thought the so-called Circle Line was the most prompt line in the London system. | Sphere | Bridge |

| 27 | b | Sarah thought the so-called circle looked more like an oval. | sphere | bridge |

| 28 | a | I didn't want to go to the inner City of LA because I thought it was dangerous. | Town | Head |

| 28 | b | I didn't want to go to the inner city because I thought it was dangerous. | town | head |

| 29 | a | We wondered if the ancient Clue set had all of its pieces. | Game | Mice |

| 29 | b | We wondered if the ancient clue was enough to solve the crime. | hint | mice |

| 30 | a | We wondered if the expensive Chef Daniel was worth the money. | Food | Bark |

| 30 | b | We wondered if the expensive chef was worth the money. | food | bark |

| 31 | a | Bobby was afraid that Coach Fred would be angry he missed the goal. | Sport | Paper |

| 31 | b | Bobby was afraid that coach seating would be miserable. | plane | paper |

| 32 | a | Bobby wanted to attend College Recruitment Day at the local high school. | Scholar | Machete |

| 32 | b | Bobby wanted to attend college in a foreign country. | scholar | machete |

| 33 | a | Charlotte couldn't remember the last Count of Barcelona had a wife. | Ruler | Glass |

| 33 | b | Charlotte couldn't remember the last count she took of the potatoes. | ruler | glass |

| 34 | a | James entered the giant Court of Appeals and was nervous about the verdict. | Judge | Heaps |

| 34 | b | James entered the giant court to try out for the JV basketball team. | hoops | heaps |

| 35 | a | She saw the tiny Crown Prince walk right past her. | Jewel | Purse |

| 35 | b | She saw the tiny crown in the museum. | jewel | purse |

| 36 | a | Debbie noticed that the little Deaf community was expanding rapidly. | Mute | Foot |

| 36 | b | Debbie noticed that the little deaf child used sign language very well. | mute | foot |

| 37 | a | I wasn't sure whether Doctor Dan would be on time for our appointment. | Health | Violin |

| 37 | b | I wasn't sure whether doctor patient confidentiality extended to children. | health | violin |

| 38 | a | Katherine wondered whether Earth would survive another million years. | World | Grade |

| 38 | b | Katherine wondered whether earth could be used as an art material. | ground | grade |

| 39 | a | He thought the cheesy Fall Dance was not worth going to. | Leaf | Flag |

| 39 | b | He thought the cheesy fall by the clown was not very convincing. | slip | flag |

| 40 | a | I waited for the next Father to be available in the confession booth. | Priest | Thorax |

| 40 | b | I waited for the next father to come pick up the student. | mother | thorax |

| 41 | a | We heard that the protected Forest of Dean was on fire and needed to be evacuated. | Nature | Pencil |

| 41 | b | We heard that the protected forest was on fire and needed to be evacuated. | nature | pencil |

| 42 | a | Don went to the special Hospital for Experimental Surgery to get the best treatment. | Surgeons | Creature |

| 42 | b | Don went to the special hospital to get the best treatment. | surgeons | creature |

| 43 | a | I played the role of the honorable Judge Judy in the school play. | Court | Rocks |

| 43 | b | I played the role of the honorable judge in the school play. | court | rocks |

| 44 | a | Jan woke up early to see the first March Flower Parade because it was so pretty. | April | Clove |

| 44 | b | Jan woke up early to see the first march of the day because her brother was in it. | stomp | clove |

| 45 | a | Joan stated that every Marine in the troop was fully prepared for deployment. | Cadets | Carpet |

| 45 | b | Joan stated that every marine creature would die outside of the water. | watery | carpet |

| 46 | a | Ross was excited to visit the famous Museum of Man he had read about all these years. | Curate | Single |

| 46 | b | Ross was excited to visit the famous museum he had read about all these years. | curate | single |

| 47 | a | Sasha heard that the retired Navy officer was coming to talk to the class. | Army | Cake |

| 47 | b | Sasha heard that the retired navy ship was now a museum. | army | cake |

| 48 | a | Everyone was worried the notorious Pirate Dinner Adventure would be crowded. | Swords | Singer |

| 48 | b | Everyone was worried the notorious pirate would attack the ship. | swords | singer |

| 49 | a | Jerry went to the respected Police Academy to become a police officer. | Patrol | Middle |

| 49 | b | Jerry went to the respected police officer to report his car stolen. | patrol | middle |

| 50 | a | On Thursday the outgoing President made his state of the union address. | Commander | Neurology |

| 50 | b | On Thursday the outgoing president of the company made a big announcement. | executive | neurology |

| 51 | a | Harry said the initial Principal was fired due to inappropriate behavior. | Authority | Bedspread |

| 51 | b | Harry said the initial principal was the amount you owed before interest. | financial | bedspread |

| 52 | a | We went to the critically acclaimed Ballet of Paris while on vacation. | Dancer | Needle |

| 52 | b | We went to the critically acclaimed ballet that was showing in Paris. | dancer | needle |

| 53 | a | I was a little surprised Senator Harry was so late for the hearing. | Nominee | Popcorn |

| 53 | b | I was a little surprised senator salaries were so high. | nominee | popcorn |

| 54 | a | We all decided that Spring was our favorite season. | Summer | Wizard |

| 54 | b | We all decided that spring hinges would work the best. | recoil | wizard |

| 55 | a | Betty found out that the very Target she shops at was going out of business. | Costco | Cheetah |

| 55 | b | Betty found out that the very target she was aiming at was already hit. | misses | cheetah |

| 56 | a | I learned about the long Trail of Tears through a history class. | Route | Crate |

| 56 | b | I learned about the long trail in Yosemite through a friend. | route | crate |

| 57 | a | When Pete was little he visited Turkey with his parents. | Mosque | Braids |

| 57 | b | When Pete was little he visited turkey farms to get a bird for Thanksgiving. | gobble | braids |

| 58 | a | Sally was eager to attend the competitive University of California summer program. | Chancellor | Redundancy |

| 58 | b | Sally was eager to attend the competitive university competition for lip syncing. | chancellor | redundancy |

| 59 | a | Sasha thought the famous Vampire Lestat was really frightening. | Dracula | Stadium |

| 59 | b | Sasha thought the famous vampire was really frightening. | dracula | stadium |

| 60 | a | Jan looked through every Wall Street Journal article on finance for her honors thesis. | Side | Lean |

| 60 | b | Jan looked through every wall to see if there were any cracks. | side | lean |

Footnotes

It should be noted that even in German, evidence for semantic preview benefits is inconsistent in that Dimigen, Kliegl, and Sommer (2012) did not find evidence for such effects using the boundary paradigm; however, the task in their experiment was not reading but rather naming lists of nouns.

It is likely that we do not see significant identical preview benefits in the lower case condition for first fixation duration and single fixation duration because these are inherently the most noisy reading time measures. Single fixation duration only includes cases in which the target word was fixated only once during first pass reading whereas gaze duration includes all first pass reading when the target was not skipped. Thus, more data are included in the gaze duration measure than in the single fixation measure: the probability of a single fixation ranged from .66 to .75, which is much lower than the probability of a gaze duration (i.e., fixation probability), which ranged from .84 to .91. Additionally, while the first fixation duration measure includes as much data as the gaze duration measure, this measure includes a mixture of single fixation durations and first fixation durations prior to a refixation (which tend to be shorter than single fixations), adding to the variability of the measure. Finally, the baseline condition in the present experiment was a word-preview; the available evidence suggests that had we used a random string of letters or degraded the letters in the preview that there would be a larger identity preview effect (Gagl, Hawelka, Richlan, Schuster, & Hutzler, 2014; Murray, Rayner, & Wakefield, 2013).

We are rather confident that the effect of first letter capitalization reported here is quite reliable as we have observed exactly the same pattern of results (a numerical and marginally significant effect in gaze duration and a fully significant effect in go-past time for capitalized words, but not for non-capitalized words) in two other studies (Schotter & Rayner, 2012). Unfortunately, we discovered a problem with the timing of the display changes in the first study. In the second study, we discovered a high degree of skipping of the pretarget word that modulated the results and decreased the power necessary to test our hypotheses; when the pretarget word was fixated, we found the same pattern of results as reported here. When the pretarget word was skipped all effects were washed out (because readers did not have adequate parafoveal preview). Thus, in the study reported here, we included a longer pretarget word to ensure that it was fixated.

References

- Altarriba J, Kambe G, Pollatsek A, Rayner K. Semantic codes are not used in integrating information across eye fixations in reading: Evidence from fluent Spanish-English bilinguals. Perception & Psychophysics. 2001;63:875–890. doi: 10.3758/bf03194444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, Bates DM. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;59:390–412. [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Pollatsek A, Rayner K. The interaction of contextual constraints and parafoveal visual information in reading. Cognitive Psychology. 1985;17:364–390. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(85)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DJ, Levy R, Scheepers C, Tily HJ. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language. 2013;68:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DM, Maechler M, Bolker B. Lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4classes. R package version 0.999375-42. 2011 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package.lme4.

- Bertram R, Hyönä J. The interplay between parafoveal preview and morphological processing in reading. In: van Gompel RPG, Fischer MH, Hill RL, editors. Eye Movements: A Window on Mind and Brain. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 391–407. [Google Scholar]

- Dearborn WF. The psychology of reading: An experimental study of the reading pulses and movements of the eye. New York: Science Press; 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch A, Frost R, Pollatsek A, Rayner K. Early morphological effects in word recognition in Hebrew: Evidence from parafoveal preview benefit. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2000;15:487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch A, Frost R, Pollatsek A, Rayner K. Morphological parafoveal preview benefit effects in reading: Evidence from Hebrew. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2005;20:341–371. [Google Scholar]

- Dimigen O, Kliegl R, Sommer W. Trans-saccadic parafoveal preview benefits in fluent reading: A study with fixation-related brain potentials. NeuroImage. 2012;62:381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engbert R, Nuthmann A, Richter E, Kliegl R. SWIFT: A dynamical model of saccade generation during reading. Psychological Review. 2005;112:777–813. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagl B, Hawelka F, Richlan F, Schuster S, Hutzler F. Parafoveal preprocessing in reading revisited: Evidence from a novel preview manipulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2014;40:588–595. doi: 10.1037/a0034408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenstein S, Kliegl R. Eye movements reveal interplay between noun class and word capitalization in reading. In: Knauff M, Pauen M, Sebanz N, Wachsmuth I, editors. Proceedings of the 35thannual conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society; 2013. pp. 2554–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenstein S, Kliegl R. Semantic preview benefit during reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2014;40:166–190. doi: 10.1037/a0033670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenstein S, Laubrock J, Kliegl R. Semantic preview benefit in eye movements during reading: A parafoveal fast-priming study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2010;36:1150–1170. doi: 10.1037/a0020233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey EB. The psychology and pedagogy of reading. New York: Macmillan; 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Hyönä J, Häikiö T. Is emotional content obtained from parafoveal words during reading? An eye movement analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2005;46:475–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2005.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambe G. Parafoveal processing of prefixed words during eye fixations in reading: Evidence against morphological influences on parafoveal preprocessing. Perception & Psychophysics. 2004;66:279–292. doi: 10.3758/bf03194879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima SD. Morphological analysis in sentence reading. Journal of Memory and Language. 1987;26:84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Miellet S, Sparrow L. Phonological codes are assembled before word fixation: Evidence from boundary paradigm in sentence reading. Brain and Language. 2004;90:299–310. doi: 10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray WS, Rayner K, Wakefield LJ. Preview benefit or preview cost?; Presented at the European Conference on Eye Movements; Lund, Sweden. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pollatsek A, Lesch M, Morris RK, Rayner K. Phonological codes are used in integrating information across saccades in word identification and reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1992;18:148–162. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.18.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. The perceptual span and peripheral cues in reading. Cognitive Psychology. 1975;7:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:372–422. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. The Thirty Fifth Sir Frederick Bartlett Lecture: Eye movements and attention during reading, scene perception, and visual search. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2009;62:1457–1506. doi: 10.1080/17470210902816461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Balota DA, Pollatsek A. Against parafoveal semantic preprocessing during eye fixations in reading. Canadian Journal of Psychology. 1986;40:473–483. doi: 10.1037/h0080111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, McConkie GW, Zola D. Integrating information across eye movements. Cognitive Psychology. 1980;12:206–226. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Pollatsek A. The Psychology of Reading. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K, Schotter ER, Drieghe D. Lack of semantic preview benefit in reading revisited. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2014 doi: 10.3758/s13423-014-0582-9. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichle ED, Pollatsek A, Fisher DL, Rayner K. Toward a model of eye movement control in reading. Psychological Review. 1998;105:125–157. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotter ER. Synonyms provide semantic preview benefit in English but other semantic relationships do not. Journal of Memory and Language. 2013;69:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotter ER, Angele B, Rayner K. Parafoveal processing in reading. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. 2012;74:5–35. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotter ER, Rayner K. Semantic preview benefit may be observed in English: The importance of initial letter capitalization (and display change delay); Meeting of the Psychonomic Society; Minneapolis, MN. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schotter ER, Reichle ED, Rayner K. Re-thinking parafoveal processing during reading: Serial attention models can explain semantic preview benefit and N+2 preview effects. Visual Cognition. 2014 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery TJ, Schotter ER, Berry RW, Rayner K. Parafoveal and foveal processing of abbreviations during eye fixations in reading: Making a case for case. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2011;37:1022–1031. doi: 10.1037/a0023215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan M, Richter EM, Shu H, Kliegl R. Readers of Chinese extract semantic information from parafoveal words. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:561. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Wang S, Tong X, Rayner K. Semantic and plausibility effects on preview benefit during eye fixations in Chinese reading. Reading and Writing. 2012;25:1031–1052. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]